Abstract

Children with medulloblastomas most commonly present with signs and symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure due to obstructive hydrocephalus, especially headaches and vomiting. However, some pediatric patients present with sudden neurological deterioration due to intracerebellar hemorrhage associated with medulloblastoma, although very few reports exist that document this phenomenon. An 8-year-old girl was admitted to our emergency department who presented with sudden loss of consciousness, vomiting, and bradycardia. The neuroradiological evaluation revealed a hemorrhagic mass lesion in the posterior fossa. Urgent evacuation of the hematoma was performed. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the postoperative histopathological examination revealed the lesion to be a medulloblastoma. This report presents an unusual case of a medulloblastoma presenting with fatal intracranial hemorrhage in a child. The clinical features and intraoperative and pathologic findings of the case are discussed.

Keywords: Cerebellar hemorrhage, childhood, medulloblastoma

Introduction

Medulloblastoma, also known as a primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the posterior fossa, is the most common malignant brain tumor in children, accounting for approximately 20–30% of all intracranial neoplasms in this group.[1] Medulloblastomas are associated with substantial mortality and morbidity. Despite aggressive multimodal treatment, including surgery, irradiation, and chemotherapy, survival rates are still unsatisfactory.

The diagnosis of medulloblastoma typically occurs when a patient comes to the emergency department for treatment. In general, computerized tomography (CT) is the first-line imaging modality for patients with medulloblastoma because of its availability in emergency departments.

The majority of patients present with symptoms that are caused by increased intracranial pressure or compression of surrounding neural structures. In rare cases, an acute intratumoral hemorrhage may be the initial presentation of medulloblastoma; this presentation can also lead to sudden neurological deterioration and even sudden death.[2,3,4,5,6,7]

Here, we report the case of a child, whose first presentation of medulloblastoma was a fatal cerebellar hemorrhage and discuss the clinical features and treatment of this tumor, including reference to the literature.

Case Report

A previously healthy 8-year-old girl was admitted to the emergency department with a sudden loss of consciousness, vomiting, and bradycardia. She was unresponsive on initial evaluation. She showed evidence of decerebrate posturing to deep painful stimulation, and her Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) was 4 points. The patient was emergently intubated and ventilated.

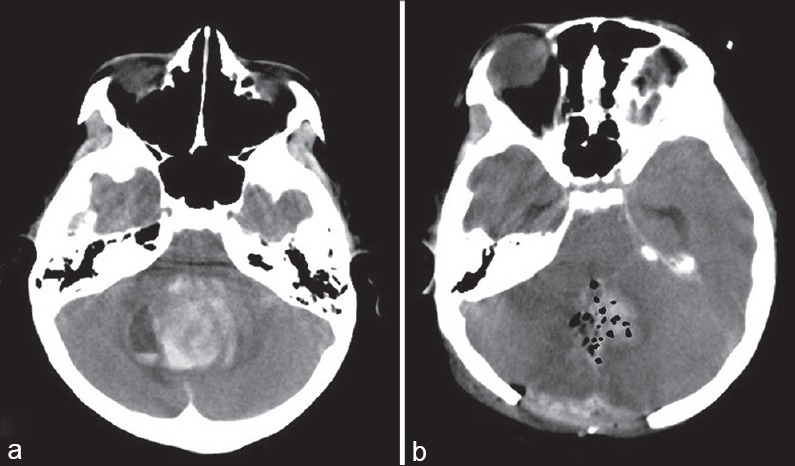

A noncontrast CT scan of her head revealed a 5 cm × 5 cm hyperdense cerebellar lesion with obliteration of the fourth ventricle and resultant obstructive hydrocephalus [Figure 1a]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not performed because of the patient's poor clinical condition. A right frontal external ventricular drain was urgently placed to relieve her high intracranial pressure. The patient was taken to the operating room, where she underwent a sub-occipital craniectomy. The intracerebellar hemorrhage was removed via standard microsurgical technique. Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit. A postoperative CT scan showed the expected postoperative changes in addition to a small amount of blood around the fourth ventricle. No residual tumor mass was detected by CT [Figure 1b]. No significant improvement in the neurological status of the patient was observed during the early postoperative period. Unfortunately, the patient died 12 h after surgery.

Figure 1.

(a) Computerized tomography scan of the brain performed at admission, showing intracerebellar hemorrhage. (b) Postoperative computerized tomography image reveals successful evacuation of the lesion

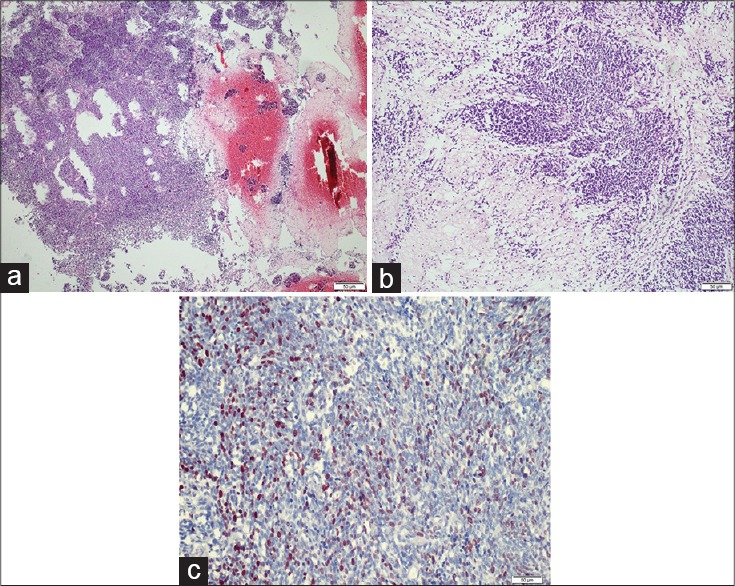

Histopathological examination of the hemorrhagic specimen identified it as a tumor mass composed of neoplastic round cells arranged in sheets and nodules, along with blood vessels and large hemorrhagic fields. The neoplastic cells demonstrated high mitotic activity, and the percentage of Ki-67 positive cells was 45–50%. The cell nuclei were round to oval in shape and had open chromatin and evidence of atypical mitosis and necrosis. Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that most of the tumor cells were strongly positive for synaptophysin and p53 and focal positive for glial fibrillary acidic protein and neuron-specific enolase. These findings were compatible with the diagnosis of medulloblastoma, Grade IV, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2007 classification criteria [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Histological examination of the resected hemorrhagic mass. (a) Necrotic and hemorrhagic tumor tissue consistent with medulloblastoma (H and E, ×40). (b) Highly cellular tumor tissue was composed of primitive neuroepithelial cells; necrosis was present (H and E, ×100). (c) Numerous tumor cell nuclei stained positive with the Ki-67 monoclonal antibody (Anti-Ki-67, ×400)

Discussion

Medulloblastomas arise from neural stem cell precursors in the granular cell layer of the cerebellum and are classified by the WHO as Grade IV tumors. Medulloblastomas account for 16% of all pediatric brain tumors and 40% of all posterior fossa tumors in childhood. The annual incidence rate of this tumor per 100,000 patients, up to 19 years in age, ranges from 0.48 in girls to 0.75 in boys. This incidence rate displays a bimodal distribution with peaks between 3–4 and 8–9 years.[1]

The signs and symptoms associated with medulloblastoma are generally dependent on the age of the child at the time of presentation. In babies and infants, the first sign of this serious disease that may be noted by clinicians is the presentation of macrocephaly with bulging anterior fontanel. Infants may also manifest other symptoms to indicate increased intracranial pressure, including vomiting, lethargy, developmental regression, and irritability. Older children have a much different presentation because their cranial sutures have fused. In keeping with the malignant nature of this type of tumor, symptoms develop rapidly over the course of approximately 3 months. Older children often present with the classic midline triad of headache, lethargy, and vomiting.

Intracerebral hemorrhage in children is relatively less common as compared to adults. The most frequent causes of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage in children are vascular malformations such as arteriovenous malformation and fistulas, or cerebral aneurysm. However, certain brain tumors can also cause intracerebral hemorrhage. In children, an acute cerebellar hemorrhage that is neoplastic in origin is rarely observed; only a few case reports of cerebellar medulloblastoma presenting with hemorrhage can be found in the literature.[2,3,4,5,6,7] Park et al. reported a 5.6% incidence of spontaneous hemorrhage in patients presenting with primary or recurrent medulloblastoma.[8]

Although spontaneous hemorrhages can be observed in rapidly growing malignant or highly vascularized tumors, the mechanisms that drive hemorrhage in medulloblastomas remain unknown. Spontaneous hemorrhaging of medulloblastomas may be associated with a variety of factors, such as structural abnormalities of the tumor vessels, tumoral invasion of vessels, increased venous pressure, undiagnosed aneurysm or vascular malformation, tumor necrosis, radiation, and external ventricular drain placement.[9] In the case presented here, histopathological examination of the specimens did not indicate a tumoral invasion of vessels or endothelial proliferation. Additionally, during the histopathological examination of the specimen obtained from the hematoma, we could not detect evidence of either aneurysm or vascular malformation; we detected only a tumor with a large necrotic and hemorrhagic area. We, therefore, hypothesize that the possible causes of this hemorrhage may have included rapid tumor growth, structural abnormalities of the vasculature, and increased local venous pressure associated with tumor expansion.

Although CT is the typical imaging modality initially used to demonstrate the presence of a medulloblastoma, MRI provides far more information about the anatomy and the extent of the tumor and is therefore more helpful in defining its features. The most common location from which these tumors arise is the midline vermis, and they generally expand into the IV ventricle. The lesions classically appear as hyperdense cerebellar masses on nonenhanced CT scans and demonstrate homogeneous enhancement following contrast injection. An initial CT scan may also reveal tumor complications, including the degree of hydrocephalus secondary to the obstruction, signs of intracranial hypertension, and tumor-related hemorrhage. CT scanning also plays an important role in the follow-up evaluation of residual tumor after resection.[10] In our case, CT scanning was performed immediately after the patient was admitted to the hospital and revealed a massive intracerebellar hemorrhage and hydrocephaly. Although MRI could have improved the preoperative diagnosis of tumor, it could not be performed because of the poor medical condition of the patient.

The treatment of medulloblastoma generally consists of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. The aim of surgery is to remove as much of the tumor as possible while minimizing damage to the rest of the brain. If increased intracranial pressure and severe hydrocephalus are identified, an external ventriculostomy catheter must be placed at the time of initial diagnosis. Tumor-related intracerebral hemorrhage is rare in the pediatric population. The prognosis following this type of hemorrhage varies based on the child's GCS at presentation. In particular, a GCS score of 3 or 4 at presentation has been associated with a significantly poorer outcome. In the case presented here, we performed external ventricular drainage to relieve the hydrocephalus and an immediate craniectomy to evacuate the posterior fossa hematoma. However, despite this urgent surgical treatment, no neurological improvement was observed in our patient.

Conclusion

This case highlights that intracerebellar hemorrhage in pediatric patients may be the first clinical sign of a tumor such as medulloblastoma, and it is usually associated with a higher mortality rate.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Illinois, USA: Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States; 2004-2005. CBTRUS. Statistical Report: (2004-2005), Primary Brain Tumors in the United States, 1997-2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santi M, Kadom N, Vezina G, Rushing EJ. Undiagnosed medulloblastoma presenting as fatal hemorrhage in a 14-year-old boy: Case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:799–805. doi: 10.1007/s00381-006-0290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furuhata M, Aihara Y, Eguchi S, Horiba A, Tanaka M, Komori T, et al. Pediatric medulloblastoma presenting as cerebellar hemorrhage: A case report. No Shinkei Geka. 2014;42:545–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elgamal EA, Richards PG, Patel UJ. Fatal haemorrhage in medulloblastoma following ventricular drainage. Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2006;42:45–8. doi: 10.1159/000089509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chugani HT, Rosemblat AM, Lavenstein BL, Palumbo FM, Luessenhop AJ, Manz HJ. Childhood medulloblastoma presenting with hemorrhage. Childs Brain. 1984;11:135–40. doi: 10.1159/000120169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCormick WF, Ugajin K. Fatal hemorrhage into a medulloblastoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1967;26:78–81. doi: 10.3171/jns.1967.26.1part1.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugawara T, Shingai J, Ogawa A, Wada T, Suzuki J, Namiki T. A case of massive fatal hemorrhage in a recurrent medulloblastoma during radiotherapy. No Shinkei Geka. 1986;14:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park TS, Hoffman HJ, Hendrick EB, Humphreys RP, Becker LE. Medulloblastoma: Clinical presentation and management. Experience at the hospital for sick children, toronto, 1950-1980. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:543–52. doi: 10.3171/jns.1983.58.4.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tachibana O, Oki H, Hayashi Y, Nonomura A, Yamashima T, Yamashita J. Repetitive intratumoral hemorrhage in medulloblastoma. A case report. Surg Neurol. 1990;33:378–83. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(90)90148-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourgouin PM, Tampieri D, Grahovac SZ, Léger C, Del Carpio R, Melançon D. CT and MR imaging findings in adults with cerebellar medulloblastoma: Comparison with findings in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:609–12. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.3.1503035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]