Abstract

Replication fork stalling at DNA lesions is a common problem during the process of DNA replication. One way to allow the bypass of these lesions is via specific recombination-based mechanisms that involve switching of the replication template to the sister chromatid. Inherent to these mechanisms is the formation of DNA joint molecules (JMs) between sister chromatids. Such JMs need to be disentangled before chromatid separation in mitosis and the activity of JM resolution enzymes, which is under stringent cell cycle control, is therefore up-regulated in mitosis. An additional layer of control is facilitated by scaffold proteins. In budding yeast, specifically during mitosis, Slx4 and Dpb11 form a cell cycle kinase-dependent complex with the Mus81-Mms4 structure-selective endonuclease, which allows efficient JM resolution by Mus81. Furthermore, Slx4 and Dpb11 interact even prior to joining Mus81 and respond to replication fork stalling in S-phase. This S-phase complex is involved in the regulation of the DNA damage checkpoint as well as in early steps of template switch recombination. Similar interactions and regulatory principles are found in human cells suggesting that Slx4 and Dpb11 may have an evolutionary conserved role organizing the cellular response to replication fork stalling.

Keywords: cell cycle, DNA damage response, homologous recombination, joint molecule resolution, post-replicative repair

Template Switch Recombination – from Initiation to Disentanglement of DNA Joint Molecules

Accurate inheritance of the genetic information is a fundamental requirement of life. DNA replication accuracy is critically dependent on the integrity of the DNA template, which is, however, constantly compromised by DNA lesions arising from intrinsic and extrinsic sources. It has been estimated that a human cell acquires between 15.000 and 100.000 DNA lesions per day.1,2 A large fraction of DNA lesions are modifications of individual bases, which affect only one DNA strand. To detect these lesions in the vast genomic landscape is challenging for cellular DNA repair pathways. Hence, the number of such base damages is estimated to be high at steady-state. Importantly, these base damages may present obstacles for replicative polymerases during DNA replication and eukaryotic cells are frequently confronted with polymerase stalling. This block needs to be overcome in order to complete replication and to avoid replication fork collapse, which causes chromosome breaks and genome instability.3

In order to bypass polymerase-stalling DNA lesions, two fundamentally different mechanisms can be utilized: translesion synthesis (TLS) and template switching (TS). In TLS, the stalled replicative polymerase is exchanged by one of several specialized translesion polymerases. These polymerases are characterized by a higher tolerance for structurally distorted DNA in their active site. This attribute allows translesion polymerases to read and synthesize across certain DNA lesions, but because of their reduced fidelity this pathway is also potentially mutagenic (see4 for a recent summary about TLS). Alternatively, cells can avoid the damaged DNA template, but utilize the already replicated sister chromatid as a template instead. Several recombination-based mechanisms have been suggested to mediate TS (Fig. 1). These include: (A) repriming and strand invasion by a gapped DNA substrate behind the replication fork, (B) controlled fork reversal and (C) fork breakdown and recombination-dependent restart. Whether all 3 mechanisms universally operate in eukaryotic cells and what the molecular determinants are is a matter of active research (see Refs.5,6 for recent summaries about TS).

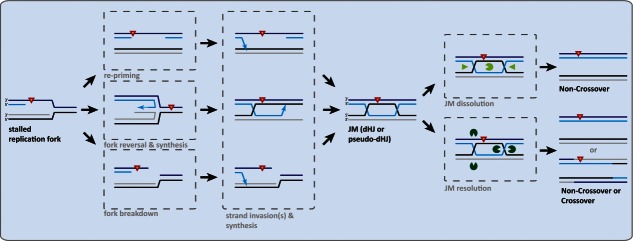

Figure 1.

Overview of recombination-based pathways to replication fork stalling. Parental DNA strands are shown in black and dark blue; newly synthesized DNA strands are shown in gray and light blue. In order to facilitate the bypass of a fork stalling DNA lesion (red triangle) template switch recombination can be initialized by different mechanisms. First, after replication fork stalling is circumvented by a re-priming event downstream of the DNA lesion, the gapped DNA may engage in a strand invasion (arrow) with the fully replicated sister chromatid behind the replication fork (post-replicative). Second, fork reversal and synthesis across the lesion (dotted arrow) may lead to the formation of JMs. Third, stalled replication fork structures may be cleaved leading to a one-ended DSBs, which may initialize strand invasion. Bypass synthesis and a second strand invasion leads to the formation of a JM, most likely in the shape of a double Holliday-Junction or pseudo Holliday-Junction (containing single-stranded DNA). These JMs can be disentangled by dissolution mechanisms yielding Non-Crossover products or by resolution mechanisms yielding a mixture of Non-Crossover and Crossover products. Alternative bypass mechanisms such as recombination-dependent restart of reversed forks/stalled replication forks leading to single Holliday junctions and requiring processing specifically by resolution enzymes are not shown.

Common to all TS mechanisms is the formation of covalent linkages between sister chromatids termed joint molecules (JMs, Fig. 1). Importantly, JMs need to be disentangled before sister chromatid separation in mitosis in order to avoid chromosome breakage. Two mechanistically distinct pathways—termed dissolution and resolution—allow JM processing (Fig. 1, Refs.7-9).

Dissolution is mediated by the yeast Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 complex (STR complex; BLM-TopoIIIα-RMI1-RMI2 (BTR complex) in vertebrates). Here, JMs (most likely having the form of double-Holliday junctions or pseudo double-Holliday junctions) are first converted to hemicatenanes by the action of the Sgs1/BLM helicase and the Top3 topoisomerase.10-12 The hemicatenanes are subsequently dissociated by the action of the Top3 topoisomerase and possibly other type IA topoisomerases.10,11,13

Resolution occurs through the action of structure-selective endonucleases. So far Slx4-Slx1, Mus81-Mms4 and Yen1 in budding yeast (SLX4-SLX1, MUS81-EME1, GEN1 in vertebrates) have been implicated in this process.8,9,14 These nucleases belong to different families and are thought to resolve Holliday junctions by different mechanisms. The XPG family nuclease Yen1 cleaves HJs by introducing two symmetrical cuts.15 In contrast, the XPF family nuclease Mus81 has a broad substrate specificity and cleaves HJs relatively poorly.16,17 Specifically in mammalian cells, it has been shown that MUS81-EME1 and SLX1-SLX4 functionally cooperate in HJ resolution.17-19 The four proteins can form a complex (SLX-MUS), which displays enhanced activity, enabling HJ resolution via a nick and counter-nick mechanism.17 Until recently however, it remained questionable whether a complex similar to SLX-MUS existed outside of the vertebrate system.20,21 It is furthermore still unclear, whether Slx1 has a general, evolutionary conserved role in processing JMs arising from stalled replication.

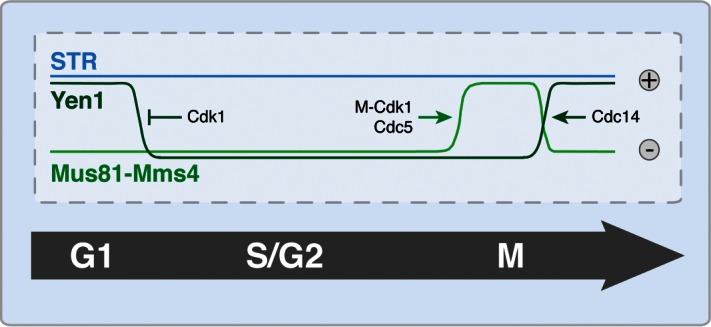

The last years have brought significant progress in our understanding of the regulation of dissolution and resolution mechanisms. In budding yeast, JM resolution by both Mus81 and Yen1 is tightly regulated by the cell cycle and restricted up until mitosis,22-26 while JM dissolution by the STR complex is cell cycle-independent (Fig. 2). Mus81-Mms4 is targeted by the cell cycle kinases Cdk1 and Cdc5 (Polo-like kinase) and these phosphorylation events strongly up-regulate the catalytic activity upon entry into mitosis (Fig. 2,24,25). Yen1 activation occurs even later in the cell cycle as it is inhibited by Cdk1 phosphorylation, and only becomes active once these phosphorylation marks are removed by the Cdc14 phosphatase in anaphase (Fig. 2,22). One reason for restriction of the resolution enzymes to mitosis may be that these nucleases need to be restrained from acting on stalled replication forks or other S-phase intermediates in order to avoid interference with the template switch reaction.27 Additionally, this cell cycle regulation creates a hierarchy in the dissolution-resolution system, enabling the STR complex to dissolve JMs before the resolution enzymes are activated. This hierarchy favors dissolution, which exclusively generates Non-Crossover products, and disfavours resolution, which results in a mixture of Crossover and Non-Crossover products. Therefore, this hierarchy may be a mechanism to protect mitotically dividing diploid cells from loss-of-heterozygosity.

Figure 2.

Activity profiles of JM processing protein complexes in S. cerevisiae throughout the cell cycle. While the Sgs1-Top3-Rmi1 complex (STR) is active at all cell cycle stages, the resolution activities of Mus81-Mms4 and Yen1 are cell cycle-regulated. Mus81-Mms4 is stimulated at the G2/M transition by M-Cdk1 and Cdc5-dependent phosphorylation. Concurrently, Cdk1 targets Yen1 by phosphorylation to inhibit its action. Upon metaphase to anaphase transition, Yen1 dephosphorylation by Cdc14 relieves this inhibition.

Recently, we described an additional layer of control in the response to stalled replication forks and in JM resolution.28 This regulation depends on the formation of a protein complex containing several scaffold proteins (Slx4, Dpb11 and Rtt107), which is exquisitely regulated by cell cycle- and DNA damage-dependent kinases. This complex can first be observed in S-phase cells and an slx4 mutation, which impairs the formation of this complex, causes defects in the response to replication fork stalling drugs, persistent DNA lesions/repair intermediates and a misregulated DNA damage checkpoint. Importantly, later in the cell cycle, in mitosis, Mus81-Mms4 joins the Slx4-Dpb11 complex thereby promoting its ability to resolve JMs.

The Slx4 and Dpb11 Scaffold Proteins Organize the Response to Replication Fork Stalling

Scaffold proteins, even though devoid of catalytic activity, have important regulatory functions in almost every cellular process. Prominent examples are Rad9 (53BP1), a mediator of the DNA damage checkpoint, and the sliding clamp PCNA, which serves as a docking site for many proteins at replication forks.29,30 In both cases, protein-protein interactions are dependent on post-translational modifications enabling a fine-tuned regulation.

The Slx4 scaffold protein has important functions in response to replication fork stalling, but also in the repair of DSBs and inter-strand crosslinks, as well as in the regulation of the DNA damage checkpoint.31-35 Accordingly, studies in mammalian cells and yeasts have identified several Slx4 binding partners and phosphorylation of Slx4 was found to be crucial for the differential regulation of the different Slx4 functions.33,35-37 However, many important questions regarding Slx4 remain unanswered. Are there distinct Slx4 complexes? How do these complexes influence each other? How similar are Slx4 functions between different organisms?

Our recent work provides new insights into the formation and the function of one Slx4-containing complex in budding yeast. This complex consists of at least three scaffold proteins—Slx4, Dpb11 and Rtt107 (Fig. 3A, Refs.28,37). In agreement with previous work37 we noticed that the formation of this complex is stimulated by replication fork stalling. The formation of the Slx4-Dpb11 complex is heavily regulated by post-translational modifications and the scaffold complex integrates at least two cellular signals: the cell cycle phase through Cdk1-dependent phosphorylation of Slx4 serine 486 and the presence of DNA lesions or repair intermediates in a DNA damage checkpoint-dependent manner.28,34,37

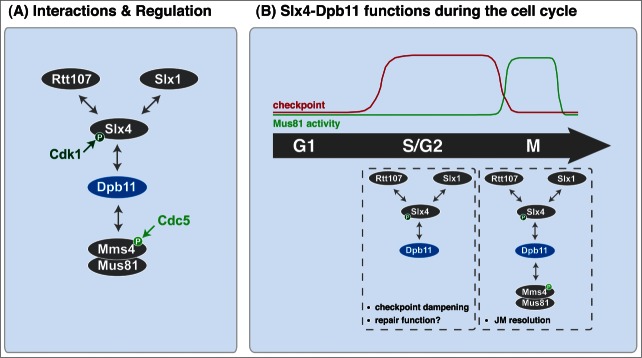

Figure 3.

Schematic model of the S-phase- and M-phase-specific Slx4-Dpb11 complexes and their regulation throughout the cell cycle (adapted from28). (A) Interactions and regulations. Upon Cdk1 phosphorylation of Slx4, interaction with Dpb11 is established. Slx4 also binds to Rtt107 and Slx1. Phosphorylation of Mms4 by Cdc5 facilitates binding of Mus81-Mms4 to Dpb11. (B) The Slx4-Dpb11 complex functions during the cell cycle. Different proteins are found in the Slx4-Dpb11 complex at different cell cycle stages suggesting distinct cell cycle phase-specific functions. The S-phase-specific complex consisting of Slx4, Dpb11, Slx1 and Rtt107 has a role in dampening the DNA damage checkpoint, but possibly also a role in repairing stalled replication forks. The M-phase-specific complex consisting of Slx4, Dpb11, Slx1, Rtt107, Mus81 and Mms4 promotes the resolution of DNA joint molecules.

Importantly, we additionally observed that the structure-selective endonuclease Mus81-Mms4 interacts with the Slx4-Dpb11 complex (Fig. 3A). While the other core subunits (Slx4, Dpb11, Rtt107, Slx1) interact during S, G2 and M-phases of the cell cycle (ref.28 and LNP and BP, unpublished), Mus81-Mms4 joins the complex specifically in M-phase.28 The association with Mus81-Mms4 is restricted to mitosis, because it is dependent on the mitotic kinase Cdc5 (Polo-like kinase). These findings immediately suggest that the composition of the Slx4-Dpb11 complex changes throughout the cell cycle and that at least two different types of complexes exist—one specific for mitosis, one found already in S/G2-phases (Fig. 3B and see below). Given the dynamic nature of the two Slx4-Dpb11 containing complexes, we cannot assess currently, whether in mitosis the S-phase complex is completely converted into the Mus81-containing M-phase complex or whether both complexes may coexist in mitotic cells.

To investigate the function of these complexes we have used a phosphorylation-site mutant in Slx4 (slx4-S486A), which shows reduced binding to Dpb11, both in the context of the S-phase Slx4-Dpb11 complex as well as in the context of the M-phase Slx4-Dpb11-Mms4-Mus81 complex.28,34 Importantly, this mutant is specifically defective in binding to Dpb11 and does not influence binding to other proteins (for example Slx1 or Rtt107). The slx4-S486A mutant phenotypes are also highly specific: mutant cells are specifically hypersensitive to the DNA alkylating agent MMS and the cellular response to MMS-induced replication fork stalling appears to be particularly affected.28 The observed phenotypes can be subdivided into two categories. The first defects manifest already in S-phase: upon MMS treatment this mutant accumulates Replication Protein A (RPA) nuclear foci compared to WT cells. These foci also dissolve more slowly compared to RPA foci of WT cells, suggesting that single-stranded DNA containing structures, potentially stalled replication forks or their repair intermediates, persist in slx4-S486A cells. Accordingly, S-phase progression is slower in MMS-treated slx4-S486A than in WT cells and the reappearance of fully replicated chromosomes is delayed, as is the switching off of the DNA damage checkpoint. Currently, the only proposed function of the S-phase Slx4-Dpb11 complex is to regulate the DNA damage checkpoint34 (and see below), but an additional repair function is possible as well.

The second class of defects can be attributed to inefficient JM resolution by the structure-selective endonuclease Mus81-Mms4 and these are therefore likely to arise from defects in the M-phase-specific Slx4-Dpb11-Mms4-Mus81 complex.28 These phenotypes become apparent in the JM dissolution-defective sgs1Δ mutant, where cells are exclusively dependent on JM resolution mechanisms in order to cope with MMS-induced replication fork stalling. Indeed, mutation of slx4-S486A causes a delay to the disappearance of JM structures in the sgs1Δ background as judged by 2D gel electrophoresis. Such persistent JMs are expected to interfere with sister chromatid separation in mitosis. Consistently, an increase in the occurrence of chromosome bridges38 is apparent in mitotic sgs1Δ slx4-S486A cells. Moreover, the slx4-S486A mutant shows reduced rates of Crossover formation in an ectopic (direct repeat) recombination assay. This finding supports the idea that the Slx4-Dpb11 complex is specifically important for JM resolution mechanisms and that slx4-S486A mutant cells rely strongly on JM dissolution by the STR complex. Notably, the JM resolution defect can be pinpointed to a defect in Mus81 function, since the slx4-S486A mutant and mus81Δ or mms4Δ show epistasis with regard to MMS hypersensitivity and turnover of JM structures. Collectively, these findings therefore suggest that the Slx4-Dpb11 complex is a regulator of Mus81-Mms4-dependent JM resolution.28

Cell Cycle Regulation of Slx4-Dpb11 Complex Formation and JM Resolution

Dpb11, and its human homolog TopBP1, specifically recognize phosphorylated proteins.39 The phosphorylation marks that are “read” by Dpb11 have been shown in several cases to depend on cell cycle kinases, in particular Cdk1. Also in the case of Slx4, phosphorylation of the critical serine 486 (a putative Cdk1 target site) is cell cycle-regulated and dependent on Cdk1 (Fig. 3A,28). In contrast, binding of Mms4 to Dpb11 (in context of the Slx4-Dpb11 complex) additionally requires phosphorylation by the mitotic kinase Cdc5, thereby restricting the formation of the Slx4-Dpb11-Mms4-Mus81 complex to mitosis (Fig. 3A).

Interestingly, Slx4-Dpb11-Mms4-Mus81 complex formation thereby underlies the same temporal regulation as the catalytic activity of Mus8123-26,28). This finding thus substantiates current models of the temporal regulation of JM resolution/dissolution (Fig. 2) providing further support for mitotic restriction of JM resolution pathways. Formation of the Slx4-Dpb11-Mms4-Mus81 complex is not responsible for the previously demonstrated enhanced catalytic activity of mitotic Mus81 in in vitro resolution assays.28 The current data therefore suggests that at least two mechanisms exist, by which cell cycle kinases control Mus81 action upon entry into mitosis: direct up-regulation of the catalytic activity and stimulation of complex formation with Slx4 and Dpb11.

It remains an open question by which mechanism the Slx4-Dpb11-Mms4-Mus81 complex enhances JM resolution by Mus81. The finding that Mus81-Mms4 is physically coupled to the Slx4-Dpb11 complex opens up the possibility that Slx4 and Dpb11 are involved in targeting to damaged chromosomes. Interestingly, the formation of the S-phase Slx4-Dpb11 complex directly responds to replication stalling. Together, these findings may suggest a speculative model, whereby the Slx4-Dpb11 complex is first recruited to sites of replication fork stalling and may subsequently escort these sites through different steps of repair. The Slx4-Dpb11 complex may thus act as a platform at sites of replication fork stalling, potentially by targeting specific repair enzymes, such as Mus81, which would catalyze the final step in the reaction.

Evolutionary Conserved Features of JM Resolution and its Regulation by Multiprotein Complexes

Mammalian cells have a temporal program of JM dissolution/resolution that is highly similar to the one found in budding yeast. JM resolution is commonly investigated in cells from Bloom's syndrome patients that are deficient in BLM-TopoIIIα-RMI1-RMI2 (BTR)-mediated JM dissolution and therefore show an increased number of crossover events/sister chromatid exchanges (SCEs,40). Mammalian JM resolution can be executed by one of three structure-selective endonucleases: MUS81-EME1, GEN1 or SLX1-SLX4. Interestingly, depletion of SLX4, SLX1 or MUS81 in cells lacking BTR exhibits a comparable reduction of SCEs as the combination of MUS81 with SLX4 or SLX1, whereas additional depletion of GEN1 leads to a more severe phenotype.17,18 These data suggest a cooperative activity of the SLX1-SLX4 and MUS81-EME1 nucleases and intriguingly, the two nucleases also physically interact with each other (SLX-MUS complex,17). The resolution of a Holliday Junction requires two cuts in order to disentangle the DNA strands and it has been suggested that SLX1 and MUS81 may cooperate as two nicking endonucleases.17

Despite conservation of the MUS81-binding SAP domain in eukaryotic Slx4 proteins,32 so far, a direct association of budding yeast Slx4 and Mus81 has not been described.21 However, both proteins are part of the Slx4-Dpb11-Mms4-Mus81 complex. Moreover, the formation of the two complexes from yeast and human is subject to a similar regulation: also the interaction between SLX1-SLX4 and MUS81-EME1 nucleases is only established at the G2/M transition involving phosphorylation by CDK1 and, to a lesser extent, PLK1.17

It is currently unclear whether the yeast Slx4-Dpb11-Mms4-Mus81 complex acts by bringing together the Mus81 and Slx1 nucleases. In fact it remains to be determined if Slx1 has an active role in this complex. A physical interaction of Slx1 with the Slx4-Dpb11 complex was detected after MMS treatment as well as in mitosis28 (L.N.P. and B.P., unpublished data), but no defects were observed in response to MMS treatment of slx1Δ deletion mutants.28,36 This suggests that either Slx1 does not play any role in JM resolution after MMS-induced replication fork stalling, or that a redundant factor may take over in the absence of Slx1.

Interestingly, also the mammalian homolog of Dpb11, TopBP1, interacts with SLX4 in a CDK phosphorylation-dependent manner.28 Whether TopBP1 also binds to MUS81-EME1, and whether SLX4-TopBP1 has a role in JM resolution in mammals needs further investigation. Intuitively, Dpb11's bridging function in yeast seems to be unnecessary in the context of the mammalian SLX-MUS complex as MUS81 directly binds to SLX4. Nevertheless, TopBP1 could be important for stabilization of the complex or for the recruitment of additional factors. On the other hand, following the observation of two cell cycle-regulated Slx4-Dpb11 complexes in yeast (S-phase- and M-phase-specific), it appears possible that TopBP1 could be involved in a function of SLX4, which is independent of MUS81, presumably in S-phase, while it may be dispensable for the mitotic function in JM resolution carried out by SLX-MUS. In other words, mammalian SLX4-TopBP1 may represent the S-phase-specific SLX4 complex, while SLX-MUS may represent the M-phase-specific SLX4 complex.

The Slx4-Dpb11 Complex and the DNA Damage Checkpoint Counteract Each Other

At least in budding yeast the Slx4-Dpb11 complex forms already in response to replication fork stalling in S-phase. One function of this S-phase complex is connected to the DNA damage checkpoint.34 The central finding of the study by Ohouo et al. is that the Slx4-Dpb11 complex regulates DNA damage checkpoint signaling. Interestingly, they found that after MMS damage the DNA damage checkpoint is hyperactivated in the slx4Δ deletion mutant. This hyperactivation can be suppressed by mutations in the checkpoint proteins Rad9 or Rad53. Importantly, also cellular viability of slx4Δ deletion mutants after MMS treatment can be improved by partially inhibiting checkpoint signaling suggesting that Slx4 acts as dampener of the DNA damage checkpoint.34

Mechanistically, checkpoint dampening may likely involve the competition between checkpoint proteins and Slx4 for Dpb11 binding. Dpb11 itself is an agonist of checkpoint signaling as it binds several checkpoint proteins, such as Rad9, the Ddc1 subunit of the 9–1–1 complex and Mec1-Ddc2.41 Here, Dpb11 functions as an activator of Mec1 and as adaptor that brings together the different checkpoint factors. Given that Dpb11 expression levels are low, it is therefore possible that by competing with checkpoint proteins Slx4 may be limiting the amounts of how much Dpb11 checkpoint complex can form. Indeed, it was shown that more Rad9 binds to Dpb11 in the absence of Slx4, suggesting that Slx4 might be a competitive inhibitor of Rad9.34

On the other hand, persistent DNA lesions/repair intermediates can be observed in MMS-treated cells deficient in Slx4-Dpb11 complex formation (see above,28). These DNA structures could be visualized as persistent RPA foci, which are expected to trigger an enhanced checkpoint activation. Indeed, checkpoint hyperactivation has been shown for other mutants with defects in the response to replication fork stalling.42,43 Thus, an underlying repair defect could be in part responsible for the checkpoint hyperactivation of slx4 mutant cells.

Is checkpoint dampening the sole function of the Slx4-Dpb11 complex in the response to replication fork stalling? Currently, we favor the idea that the Slx4-Dpb11 complex has an additional repair function in response to replication fork stalling. First, the slx4-S486A mutant is specifically sensitive to MMS but not to other kinds of DNA damaging agents, while the checkpoint responds universally to different kinds of DNA damage.28,34 Second, this sensitivity is rescued by expression of an artificial covalent fusion of Dpb11 and Slx4.28 In these experiments the Dpb11-Slx4 fusion is expressed as a second copy of Dpb11. Due to the high levels of Dpb11 this mutant should be deficient in checkpoint dampening, but the hypersensitivity to MMS is rescued nonetheless. Until today, however, no repair enzyme was found to interact with the S-phase Slx4-Dpb11 complex and it therefore remains to be determined what this additional repair function of the Slx4-Dpb11 complex may be.

Interestingly, not only does the S-phase Slx4-Dpb11 complex counteract the DNA damage checkpoint, but the DNA damage checkpoint also counteracts the M-phase Slx4-Dpb11 complex. After its activation by MMS damage the checkpoint appears to delay Mms4 phosphorylation by Cdc5 and thereby Mus81-Mms4 activation thereby creating a second layer of temporal regulation that is in addition to the cell cycle control26,28 (Fig. 3B).

Do the early functions of the Slx4-Dpb11 complex in S-phase therefore have an influence on the later stages of the cell cycle? Strikingly, in addition to directly promoting Mus81 function in JM resolution, the Slx4-Dpb11 complex may promote Mus81 activity indirectly by checkpoint regulation. Notably, the partial inactivation of the checkpoint by the ddc1-T602A mutant promotes earlier Mms4 phosphorylation by Cdc5 in cells that have an impaired Dpb11-Slx4 interaction.28 Moreover, also the rescue of slx4 mutant sensitivity by partial checkpoint inactivation strictly depends on Mus81-Mms4. This suggests that the checkpoint dampening function in S-phase may be connected to the later JM resolution function of the Slx4-Dpb11 complex in M-phase.

Conclusion

The response to replication fork stalling is strictly regulated during the cell cycle. A means of integrating these cell cycle signals appears to be the formation of multiprotein complexes containing scaffold proteins. At least two Slx4-Dpb11 complexes act during the response to stalled replication forks: an S-phase complex, which regulates the DNA damage checkpoint and possibly has a DNA repair function as well, and an M-phase complex, which additionally contains Mus81-Mms4 and promotes JM resolution. Future research will need to identify additional repair factors in the S-phase complex and to investigate the crosstalk between the two complexes in order to shed light on the rather enigmatic cellular response to replication fork stalling.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dana Branzei, Stefan Jentsch, Michael Lisby, Joao Matos and members of the Pfander and Jentsch labs for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding

Work in the Pfander lab is supported by the Max-Planck Society and the German Research Council (DFG). The authors declare that they have no competing financial interest.

References

- 1. Hoeijmakers JHJ. DNA damage, aging, and cancer. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1475-85; PMID:19812404; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMra0804615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lindahl T, Barnes DE. Repair of endogenous DNA damage. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2000; 65:127-33; PMID:12760027; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Branzei D, Foiani M. Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11:208-19; PMID:20177396; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sale JE. Translesion DNA synthesis and mutagenesis in eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2013; 5:a012708; PMID:23457261; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a012708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Branzei D. Ubiquitin family modifications and template switching. FEBS Letters 2011; 585:2810-2817; PMID:21539841; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ulrich HD. Timing and spacing of ubiquitin-dependent DNA damage bypass. FEBS Letters 2011; 585:2861-7; PMID:21605556; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mankouri HW, Huttner D, Hickson ID. How unfinished business from S-phase affects mitosis and beyond. Embo J 2013; 32:2661-71; PMID:24065128; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2013.211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matos J., West SC. Holliday junction resolution: regulation in space and time. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2014; 19:176-81; PMID:24767945; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sarbajna S, West SC. Holliday junction processing enzymes as guardians of genome stability. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2014; 39:409-19; PMID:25131815; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cejka P, Plank JL, Bachrati CZ, Hickson ID, Kowalczykowski SC. Rmi1 stimulates decatenation of double holliday junctions during dissolution by sgs1–top3. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2010; 17:1377-82; PMID:20935631; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cejka P, Plank JL, Dombrowski CC, Kowalczykowski SC. Decatenation of DNA by the S. cerevisiae sgs1-Top3-rmi1 and RPA complex: a mechanism for disentangling chromosomes. Mol Cell 2012; 47:886-96; PMID:22885009; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giannattasio M, Zwicky K, Follonier C, Foiani M, Lopes M, Branzei D. Visualization of recombination-mediated damage bypass by template switching. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2014; 10:884-92; PMID:25195051; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bizard AH, Hickson ID. The dissolution of double holliday junctions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2014; 6:a016477; PMID:24984776; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a016477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mankouri HW, Ashton TM, Hickson ID. Holliday junction-containing DNA structures persist in cells lacking sgs1 or top3 following exposure to DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108:4944-9; PMID:21383164; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1014240108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ip SCY, Rass U, Blanco MG, Flynn HR, Skehel JM, West SC. Identification of holliday junction resolvases from humans and yeast. Nature 2008; 456:357-61; PMID:19020614; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature07470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Boddy MN, Gaillard PH, McDonald WH, Shanahan P, Yates JR, Russell P. Mus81-eme1 are essential components of a holliday junction resolvase. Cell 2001; 107:537-48; PMID:11719193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00536-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wyatt HDM, Sarbajna S, Matos J, West SC. Coordinated actions of SLX1-SLX4 and MUS81-EME1 for holliday junction resolution in human cells. Mol Cell 2013; 52:234-47; PMID:24076221; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Castor D, Nair N, Déclais A-C, Lachaud C, Toth R, Macartney TJ, Lilley DMJ, Arthur JSC, Rouse J. Cooperative control of holliday junction resolution and DNA repair by the SLX1 and MUS81-EME1 nucleases. Mol Cell 2013; 52(2), 221-33; PMID:24076219; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sarbajna S, Davies D, West SC. Roles of SLX1-SLX4, MUS81-EME1, and GEN1 in avoiding genome instability and mitotic catastrophe. Genes Dev 2014; 28:1124-36; PMID:24831703; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.238303.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mukherjee S, Wright WD, Ehmsen KT, Heyer WD. The mus81-mms4 structure-selective endonuclease requires nicked DNA junctions to undergo conformational changes and bend its DNA substrates for cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:6511-22; PMID:24744239; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gku265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schwartz EK, Wright WD, Ehmsen KT, Evans JE, Stahlberg H, Heyer WD. Mus81-Mms4 functions as a single heterodimer to cleave nicked intermediates in recombinational DNA repair. Mol Cell Biol 2012; 32:3065-80; PMID:22645308; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.00547-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blanco MG, Matos J, West SC. Dual control of yen1 nuclease activity and cellular localization by cdk and cdc14 prevents genome instability. Mol Cell 2014; 54:94-106; PMID:24631285; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gallo-Fernández M, Saugar I, Ortiz-Bazán MÁ, Vázquez MV, Tercero JA. Cell cycle-dependent regulation of the nuclease activity of mus81-eme1/mms4. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:8325-35; PMID:22730299; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gks599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Matos J, Blanco MG, West SC. Cell-cycle kinases coordinate the resolution of recombination intermediates with chromosome segregation. Cell Rep 2013; 4:76-86; PMID:23810555; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matos J, Blanco MG, Maslen S, Skehel JM, West SC. Regulatory control of the resolution of DNA recombination intermediates during meiosis and mitosis. Cell 2011; 147:158-72; PMID:21962513; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Szakal B, Branzei D. Premature cdk1/cdc5/mus81 pathway activation induces aberrant replication and deleterious crossover. Embo J 2013; 32:1155-67; PMID:23531881; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2013.67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saugar I, Vazquez MV, Gallo-Fernandez M, Ortiz-Bazan MA, Segurado M, Calzada A, Tercero JA. Temporal regulation of the mus81-mms4 endonuclease ensures cell survival under conditions of DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res 2013; 41:894358; PMID:23901010; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkt645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gritenaite D, Princz LN, Szakal B, Bantele SCS, Wendeler L, Schilbach S, Habermann BH, Matos J, Lisby M, Branzei D, et al. A cell cycle-regulated slx4-dpb11 complex promotes the resolution of DNA repair intermediates linked to stalled replication. Genes Dev 2014; 28:1604-19; PMID:25030699; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.240515.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Finn K, Lowndes NF, Grenon M. Eukaryotic DNA damage checkpoint activation in response to double-strand breaks. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011; 69:1447-73; PMID:22083606; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-011-0875-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moldovan G-L, Pfander B, Jentsch S. PCNA, the maestro of the replication fork. Cell 2007; 129:665-79; PMID:17512402; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Douwel DK, Boonen RACM, Long DT, Szypowska AA., Räschle M, Walter JC, Knipscheer P. XPF-ERCC1 Acts in unhooking DNA interstrand crosslinks in cooperation with FANCD2 and FANCP/SLX4. Mol Cell 2014; 54:460-71; PMID:24726325; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fekairi S, Scaglione S, Chahwan C, Taylor ER, Tissier A, Coulon S, Dong M-Q, Ruse C, Yates JR, Russell P, et al. Human SLX4 is a holliday junction resolvase subunit that binds multiple DNA repair/recombination endonucleases. Cell 2009; 138:78-89; PMID:19596236; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim Y, Spitz GS, Veturi U, Lach FP, Auerbach AD, Smogorzewska A. Regulation of multiple DNA repair pathways by the fanconi anemia protein SLX4. Blood 2013; 121:54-63; PMID:23093618; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2012-07-441212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ohouo PY, de Oliveira FMB, Liu Y, Ma CJ, Smolka MB. DNA-repair scaffolds dampen checkpoint signalling by counteracting the adaptor rad9. Nature 2012; 493:120-4; PMID:23160493; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Svendsen JM, Smogorzewska A, Sowa ME, O'Connell BC, Gygi SP, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. Mammalian BTBD12/SLX4 assembles a holliday junction resolvase and is required for DNA repair. Cell 2009; 138:63-77; PMID:19596235; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Flott S, Alabert C, Toh GW, Toth R, Sugawara N, Campbell DG, Haber JE, Pasero P, Rouse J. Phosphorylation of Slx4 by mec1 and tel1 regulates the single-strand annealing mode of DNA repair in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27:6433-45; PMID:17636031; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.00135-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ohouo PY, de Oliveira FMB, Almeida BS, Smolka MB. DNA Damage signaling recruits the rtt107-slx4 scaffolds via dpb11 to mediate replication stress response. Mol Cell 2010; 39:3006; PMID:20670896; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Germann SM, Schramke V, Pedersen RT, Gallina I, Eckert-Boulet N, Oestergaard VH, Lisby M. TopBP1/dpb11 binds DNA anaphase bridges to prevent genome instability. J Cell Biol 2014; 204:45-59; PMID:24379413; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201305157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wardlaw CP, Carr AM, Oliver AW. TopBP1: A BRCT-scaffold protein functioning in multiple cellular pathways. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2014; 22:165-174; PMID:25087188; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ray JH, German J. Bloom's syndrome and EM9 cells in BrdU-containing medium exhibit similarly elevated frequencies of sister chromatid exchange but dissimilar amounts of cellular proliferation and chromosome disruption. Chromosoma 1984; 90:383-8; PMID:6510115; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00294165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pfander B, Diffley JFX. Dpb11 coordinates mec1 kinase activation with cell cycle-regulated rad9 recruitment. Embo J 2011; 30:4897-907; PMID:21946560; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2011.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen Y-H, Szakal B, Castellucci F, Branzei D, Zhao X. DNA damage checkpoint and recombinational repair differentially affect the replication stress tolerance of smc6 mutants. Mol Biol Cell 2013; 24:2431-41; PMID:23783034; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E12-11-0836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Karras GI, Jentsch S. The RAD6 DNA damage tolerance pathway operates uncoupled from the replication fork and is functional beyond S phase. Cell 2010; 141:255-67; PMID:20403322; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]