Abstract

Objective

This study examined veterans' responses to the Veterans Health Administration's (VHA's) universal screen for homelessness and risk of homelessness during the first 12 months of implementation.

Methods

We calculated the baseline annual frequency of homelessness and risk of homelessness among all veterans who completed an initial screen during the study period. We measured changes in housing status among veterans who initially screened positive and then completed a follow-up screen, assessed factors associated with such changes, and identified distinct risk profiles of veterans who completed a follow-up screen.

Results

More than 4 million veterans completed an initial screen; 1.8% (n=77,621) screened positive for homelessness or risk of homelessness. Of those who initially screened positive for either homelessness or risk of homelessness and who completed a second screen during the study period, 85.0% (n=15,060) resolved their housing instability prior to their second screen. Age, sex, race, VHA eligibility, and screening location were all associated with changes in housing stability. We identified four distinct risk profiles for veterans with ongoing housing instability.

Conclusion

To address homelessness among veterans, efforts should include increased and targeted engagement of veterans experiencing persistent housing instability.

Addressing homelessness among veterans is a top policy priority at the federal, state, and local levels. To this end, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) developed a comprehensive plan to prevent and end homelessness among veterans,1 emphasizing prevention-oriented strategies and investing substantial resources in novel approaches, most notably the Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) program.2 To date, these efforts have garnered notable success; the number of veterans experiencing homelessness on a given night nationwide declined from 74,050 to 55,779—a 24% decrease—from 2009 to 2013.3

Identifying veterans who are at risk of homelessness—or are experiencing homelessness but are not accessing services through Veterans Health Administration (VHA) homeless programs—is crucially important for continued progress toward ending veteran homelessness. A recent study found that more than one-third of a cohort of newly homeless veterans used mainstream homeless assistance services but did not access VHA homeless programs, suggesting that a sizable number of veterans experiencing homelessness or risk of homelessness (hereinafter referred to as “risk”) may not be linked with VA resources that may improve their housing stability.4

To improve the VA's ability to identify these veterans and refer them appropriately, VHA implemented a universal, two-question screener for current homelessness and imminent risk—the Homelessness Screening Clinical Reminder (HSCR)—that is administered at all VHA health-care facilities. During the first three months of its implementation (October 1, 2012, to January 10, 2013), 0.9% of respondents reported current homelessness, 1.2% reported imminent risk, and 97.9% screened negative for both.5 However, this observation period was unable to account for known seasonal trends in the size of the homeless population6 and did not allow for an assessment of multiple responses to the HSCR, which would indicate subsequent changes in housing status over time. The present study builds on these findings, using data collected by the HSCR during its first year of implementation.

The aims for this study were to (1) estimate the baseline annual prevalence rates of homelessness and risk among veterans who accessed VHA outpatient health care during federal fiscal year (FY) 2013, (2) measure changes in housing stability for veterans who initially screened positive and completed a follow-up screening during FY 2013 and identify factors associated with those changes, and (3) identify distinct risk profiles of veterans who are experiencing persistent housing instability.

METHODS

The HSCR

The HSCR comprises two primary questions, which have good psychometric properties:7

In the past two months, have you been living in stable housing that you own, rent, or stay in as part of a household? (Negative response indicates homelessness.)

Are you worried or concerned that in the next two months you may NOT have stable housing that you own, rent, or stay in as part of a household? (Positive response indicates risk of homelessness.)

Veterans who screen positive for homelessness or risk are asked where they have lived for most of the previous two months and if they would like a referral to discuss their living situation further. The HSCR is administered annually to all veterans accessing outpatient care, with the exception of veterans who are already receiving homeless assistance or living in a long-term care facility. Veterans who screen positive for homelessness or risk or decline screening are rescreened semiannually, while those who screen negative are rescreened annually.

Sample

The study sample comprised all veterans who responded to the HSCR from October 1, 2012, to September 30, 2013, excluding 43,011 veterans who declined a screening, were recorded as being <18 or >115 years of age, or had incomplete responses; and an additional 17,104 veterans who did not respond to the HSCR because they reported being already homeless, reported living in a nursing home or receiving palliative care, or were unable to respond. The final sample included 4,307,764 veterans.

Measures

We coded veterans' responses to the HSCR as homeless, at risk, and negative. The data, stored in the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse,8 included responses to the HSCR, the outpatient clinic type where staff administered the HSCR, and whether or not veterans who screened positive for homelessness or risk accepted a referral to VHA social work or homeless services. For veterans who completed a rescreen at least six months after an initial positive screen, we constructed a five-level categorical outcome variable to measure changes in screening disposition:

Resolved housing instability: veterans who screened positive for homelessness or risk on their initial screen but negative for both on their rescreen,

Persistently homeless: veterans who screened positive for homelessness on initial and follow-up screens,

Persistently at risk: veterans who screened positive for risk on initial and follow-up screens,

Newly homeless: veterans who initially screened positive for risk and rescreened positive for homelessness, and

Homeless to risk: veterans who initially screened positive for homelessness and rescreened positive for risk.

Demographic variables included age, sex, and race/ethnicity. We included an indicator of whether a veteran had been deployed in either Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). Veterans' eligibility for VHA health care was based on VHA's Enrollment Priority Groups, which indicate the extent to which a veteran is receiving compensation due to a disability incurred during military service as well as whether or not a veteran is very low income. We collapsed these groups into five categories: (1) no service-connected disability and not Medicaid-eligible, which included veterans who were neither disabled nor low income; (2) no service-connected disability but Medicaid-eligible, which included veterans who were not disabled but low income; (3) service-connected disability <50% disabling; (4) service-connected disability ≥50% disabling; and (5) veterans meeting other criteria for eligibility.9

Geographic variables included whether or not veterans responded to the HSCR at a rural location, based on designations made by the VHA Support Service Center. We also used the U.S. Census Bureau's region divisions10 to identify the region of the country where veterans responded to the HSCR; roughly 1% of veterans completed the HSCR in VHA facilities in either Puerto Rico or the Philippines and were categorized as such in all analyses.

Analysis

We computed the frequency of initial positive responses to the HSCR for current or imminent risk of homelessness during the 12-month observation period. We used descriptive statistics to examine the distribution and respective characteristics of the five groups of veterans who completed a rescreen. A multinomial mixed-effect regression model was estimated with SAS® version 9.211 using SAS PROC GLIMMIX to examine the relationship between rescreen disposition (based on the five-level variable) and the acceptance of a referral, as well as the demographic, OEF/OIF service, VHA Enrollment Priority Groups, geographic location, and screening environment variables. The model included a variable for the length of time between initial screen and rescreen to control for a possible relationship between the amount of time between screenings and the probability of a change in housing status. Facility-specific random intercepts were used to control for clustering within VA facilities where veterans completed the HSCR.

To better understand the profile of veterans who rescreened positive vs. negative for homelessness, we conducted a latent class analysis (LCA) to determine if specific subgroups were more prevalent among those rescreening positive for homelessness or risk. Variables included in the LCA models were age group, sex, race (white, nonwhite), period of service, OEF/OIF deployment, geographic region, rural/urban designation, living situation at the first positive screen (housed, staying with family or friend, motel/hotel/institution, shelter/street, or other), VA Enrollment Priority Group, acceptance of a referral at the first screen, VHA clinic location of first screen (mental health, substance abuse, primary care, or other), and whether the veteran had a chronic health, mental health, or substance abuse condition. To measure these conditions, we used the algorithm developed by Elixhauser and colleagues12 to identify a set of medical comorbidities based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes13 in veterans' electronic health records as well as three additional comorbidities: traumatic brain injury (TBI),14 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicide and intentional self-inflicted injury. Chronic health conditions included TBI and any of 15 Elixhauser health comorbidities. Mental health condition included psychoses and major depression defined by the Elixhauser algorithm as well as PTSD and suicide. Substance abuse disorder included a drug or alcohol disorder. We conducted the LCA using the poLCA package in R15 and estimated separate models for subgroups rescreening positive and negative for homelessness, as we hypothesized that their profiles would be substantially different. For each subgroup, we estimated a series of LCA models specifying one through 10 classes and selected the best fitting model based on the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion with the smallest number of clusters.

RESULTS

Annual prevalence of homelessness and risk

Among the more than 4.3 million unique veterans who responded to the HSCR from October 1, 2012, to September 30, 2013, 36,081 (0.8%) screened positive for current homelessness, 41,540 (1.0%) screened positive for imminent risk, and the remaining 4,230,143 (98.2%) screened negative.

Changes in screening disposition of veterans with an initial positive screen

Among the 77,621 veterans with an initial positive screen for either homelessness or risk, 52,188 (67.2%) were eligible for a rescreen during the study period (i.e., their initial screen occurred at least six months prior to the end of the study period); of these 52,188 veterans who were eligible for a rescreen, 17,720 (34.0%) responded to a subsequent screen 6–12 months after the first screen. The remaining 34,468 veterans did not complete a follow-up screen, primarily because they did not have an outpatient visit during this period. Bivariate analysis found that, compared with veterans who did complete a rescreen, those who did not were younger; more likely to be male, to accept a referral after an initial positive screen, to have served in OEF/OIF, and to have been screened in a primary care setting; but were less likely to be white or to have a service-connected disability.

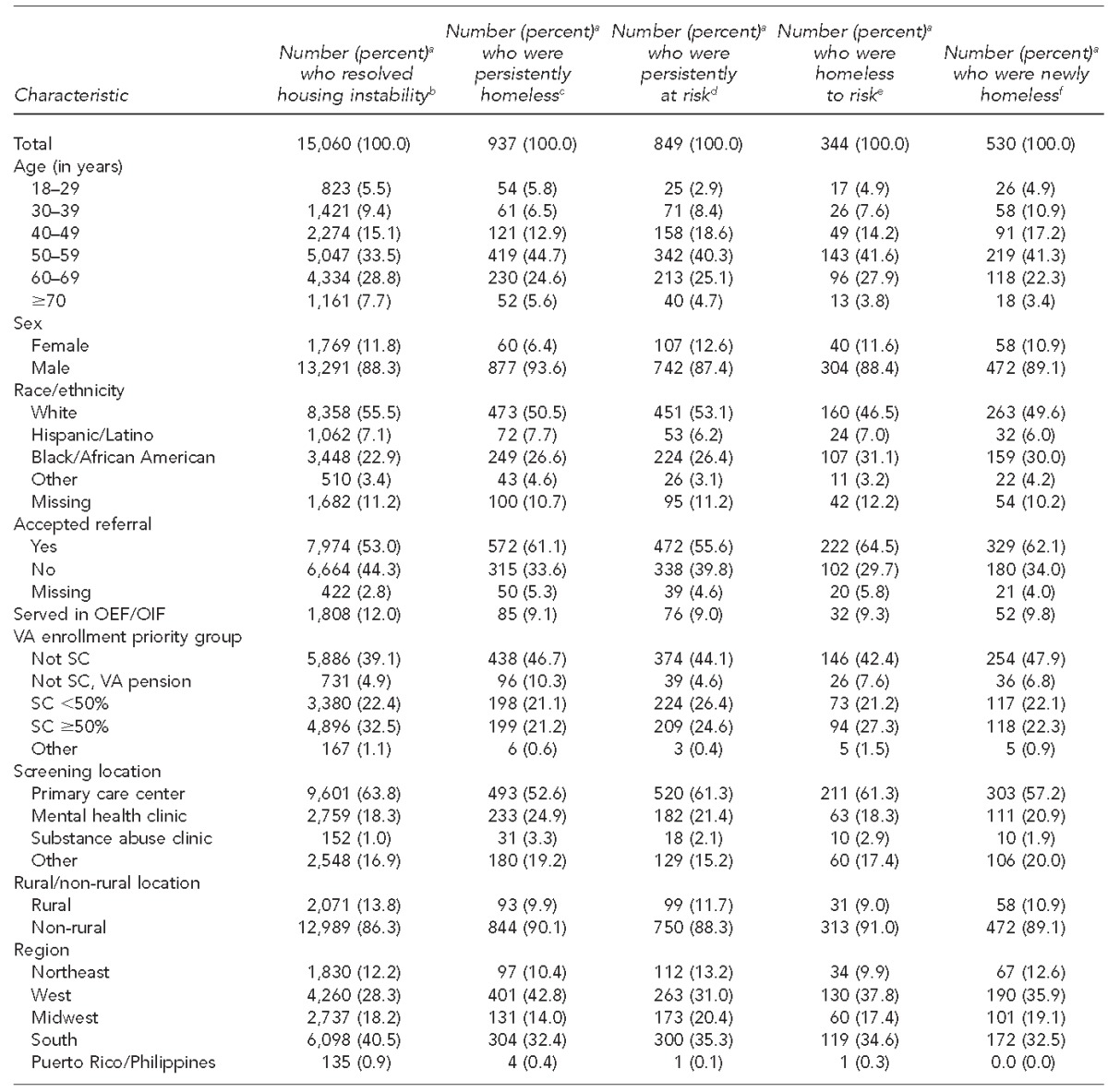

The vast majority of veterans who completed a follow-up screen (85.0%, n=15,060) rescreened negative for either homelessness or risk (resolved housing instability group). Of veterans who rescreened negative, 5.3% (n=937) were persistently homeless, 4.8% (n=849) were persistently at risk, 3.0% (n=530) were newly homeless, and 1.9% (n=344) were homeless to risk. The characteristics of veterans in the five rescreen groups are shown (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of U.S. veterans with an initial positive response to the Homelessness Screening Clinical Reminder during federal fiscal year 2013 who also responded to a follow-up screen during federal fiscal year 2013 (n=17,720)

aPercentages do not always sum to 100 because of rounding.

bVeterans who screened positive for homelessness or risk on their initial screen but negative for both on their follow-up screen

cVeterans who screened positive for homelessness on initial and follow-up screens

dVeterans who screened positive for risk on initial and follow-up screens

eVeterans who initially screened positive for risk and rescreened positive for homelessness

fVeterans who initially screened positive for homelessness and rescreened positive for risk

OEF = Operation Enduring Freedom

OIF = Operation Iraqi Freedom

VA = Veterans Affairs

SC = service-connected disability

Factors associated with changes in screening disposition

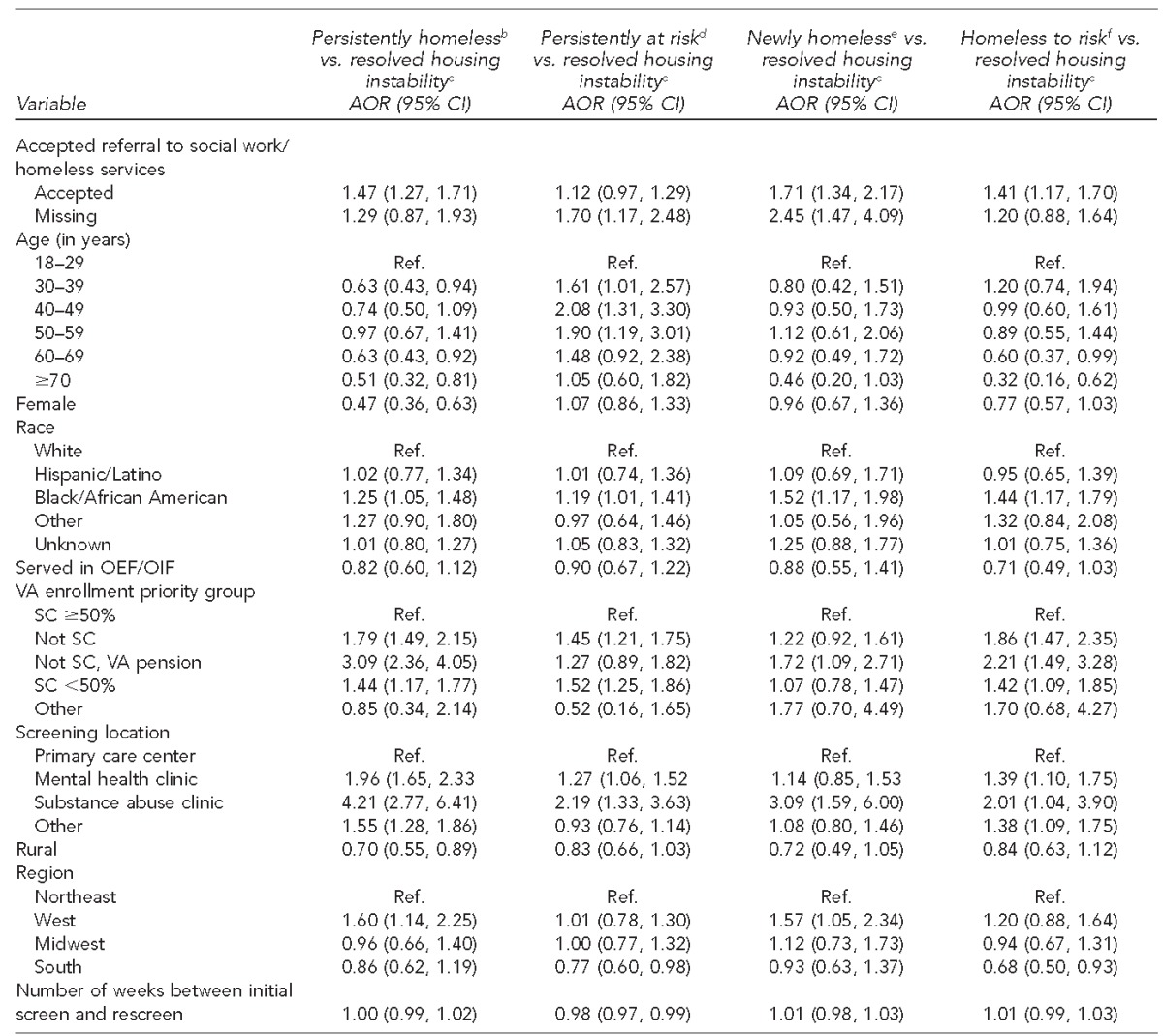

The results of the mixed-effect multinomial logistic regression model are shown (Table 2). Compared with veterans who declined a referral to homeless or social work services following their initial positive screen, those who accepted a referral had greater odds of being in the persistently homeless (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.47, 95% confidence interval 1.27, 1.71), newly homeless (AOR=1.71, 95% CI 1.34, 2.17), or homeless to risk (AOR=1.41, 95% CI 1.17, 1.70) groups, relative to the resolved housing instability group. Older age was generally associated with a decreased likelihood of being in the persistently homeless group rather than the resolved housing instability group, but an increased likelihood of being in the persistently at risk group. Female veterans were about half as likely as male veterans to be in the persistently homeless group (AOR=0.47, 95% CI 0.36, 0.63), but sex was otherwise not a significant predictor of homelessness. There were no significant associations between OEF/OIF deployment and group membership. VA Enrollment Priority Group fairly consistently predicted veterans' positive rescreens; those with <50% or no service-connected disability were generally more likely to be in response groups other than the resolved housing instability group. Veterans who did not have a service-connected disability but were receiving a VA pension were approximately three times as likely to be in the persistently homeless group than the resolved housing instability group.

Table 2.

Mixed-effect multinomial logistic regression model predicting change in housing stability category among veterans with an initial positive response to the Homelessness Screening Clinical Reminder during federal fiscal year 2013 who also responded to a follow-up screen during federal fiscal year 2013 (n=17,579)a

The models exclude 141 veterans who rescreened positive in Puerto Rico or the Philippines, as the inclusion of these veterans created sparsely populated cells and caused problems with model convergence.

bVeterans who screened positive for homelessness on initial and follow-up screens

cVeterans who screened positive for homelessness or risk on their initial screen but negative for both on their follow-up screen

dVeterans who screened positive for risk on initial and follow-up screens

eVeterans who initially screened positive for risk and rescreened positive for homelessness

fVeterans who initially screened positive for homelessness and rescreened positive for risk

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

Ref. = reference group

OEF = Operation Enduring Freedom

OIF = Operation Iraqi Freedom

VA = Veterans Affairs

SC = service-connected disability

Veterans who responded to the HSCR in a mental health clinic were about twice as likely as those screened in primary care to be in the persistently homeless (AOR=1.96, 95% CI 1.65, 2.33) and persistently at risk (AOR=1.27, 95% CI 1.06, 1.52) groups compared with the resolved housing instability group. Those screened in substance abuse clinics were roughly four times as likely (AOR=4.21, 95% CI 2.77, 6.41) as those screened in primary care to be in the persistently homeless group and three times as likely to be in the newly homeless group (AOR=3.09, 95% CI 1.59, 6.00). Rural screening location, geographic region, and length of time between initial screen and rescreen were not consistent predictors of group membership (Table 2).

Results of LCA identifying distinct risk profiles

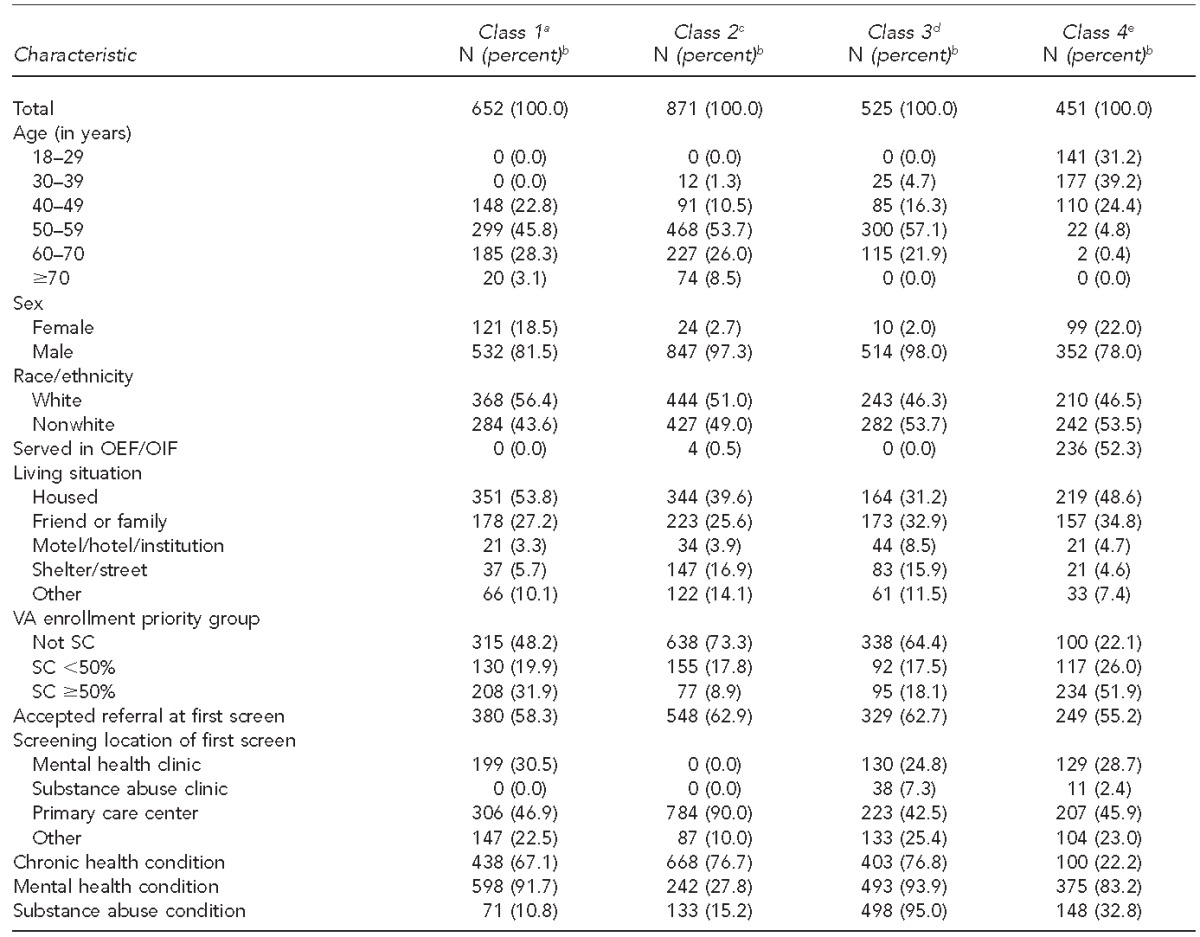

A best-fitting LCA model was not found for negative rescreens (n=15,060), suggesting no observable patterns or subgroups among those who did not rescreen positive for homelessness or risk. We dropped four variables from the LCA models that did not contribute to the identification of subgroups: marital status, race, period of service, and region. For positive rescreens (n=2,499; at risk or homeless), the best-fitting LCA model included four classes (Table 3):

Older veterans with mostly mental health issues (26.1%, n=652);

Older veterans with primarily physical health issues but no VA service-connected disability (34.9%, n=871);

Older veterans with a complex mix of physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions but no VA service-connected disability, resembling chronically homeless individuals (21.0%, n=525); and

Younger veterans transitioning from military discharge (18.0%, n=451).

Table 3.

Results of latent class analysis among U.S. veterans with an initial positive response to the Homelessness Screening Clinical Reminder during federal fiscal year 2013 who also had a positive response on a follow-up screen during federal fiscal year 2013 (n=2,499)

aClassified as older veterans with mostly mental health issues

bPercentages do not always sum to 100 because of rounding.

cClassified as older veterans with primarily physical health issues but no SC

dClassified as older veterans with a complex mix of physical, mental, and substance abuse conditions but no SC

eClassified as younger veterans transitioning from military discharge

OEF = Operation Enduring Freedom

OIF = Operation Iraqi Freedom

VA = Veterans Affairs

SC = service-connected disability

DISCUSSION

Among the more than 4 million veterans who completed the HSCR during its initial year of -implementation, 1.8% reported current homelessness or imminent risk. While only a small fraction of the 8.9 million veterans enrolled in VHA health care in FY 2013, it represents a sizable number in absolute terms. Fortunately, recent expansions of programs to provide permanent supportive housing to veterans through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) and SSVF programs make it feasible to assist the large majority of veterans with housing instability.

Among veterans who initially screened positive for either current homelessness or homelessness risk and who completed a rescreen 6–12 months later, only 15.0% reported either type of housing instability at their rescreen. This finding is consistent with prior research demonstrating that only a small fraction of households remains homeless for an extended duration,16 and suggests that most veterans in this group experienced only brief periods of housing instability. However, households that remain homeless for longer periods of time tend to have more intensive health and behavioral health needs,16 making it especially important to target veterans who report housing instability on successive screening occasions for intervention.

Veterans who accepted a referral following an initial positive screen were more likely to be in the persistently homeless or newly homeless groups; this increased likelihood indicates that accepting a referral could serve as an additional item to identify veterans with more intensive housing crises. It also underscores the importance of connecting veterans who do accept a referral with housing and health-care services that match their needs. Although the present study did not identify whether and what services were ultimately provided to veterans who accepted a referral, several follow-up studies will examine this issue more closely.

Veterans receiving lower levels of VA compensation had higher odds of being in the persistently homeless, persistently at risk, and newly homeless groups. This relationship likely reflects the fact that the increased benefits available to veterans who became disabled through military service are protective. Outreach efforts to enroll veterans who are eligible for such benefits may be cost effective to the extent that they can help avoid the high costs associated with long-term homelessness.17–21 This finding should be understood in conjunction with the finding that veterans who experienced persistent homelessness or homelessness risk were disproportionately screened in mental health and substance abuse treatment clinics, suggesting higher rates of behavioral health problems in these groups. Taken together, these two findings may mean that veterans who have a non-service-related disability, and who therefore cannot access the benefits available to their service-disabled counterparts, are a particularly vulnerable group for persistent housing problems.

The distinct risk profiles that were identified by the LCA suggest that veterans who experience persistent housing instability are not a homogenous group with respect to their likely housing and health-care needs. The class of older veterans with complex health and behavioral health issues are likely prime candidates for ongoing housing and supportive services available through the HUD-VASH program, while the class of younger veterans may only require short-term assistance available through SSVF to regain housing stability. Veterans in the other two classes (older veterans with primarily mental health or primarily physical issues) may require targeted assistance through VHA to maintain stable housing and avoid the need for other more expensive forms of care, such as nursing home placement. In this respect, VHA's Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team, which uses a medical home model to help veterans access health care and housing services, may be especially appropriate for veterans in these classes. The results of the LCA also suggest that a new benefit that provides income support to a targeted group of veterans—documented housing instability, ineligible for a VA pension or Supplemental Security Income, too young for Social Security—may be a worthwhile investment.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. First, the HSCR was not administered in inpatient or emergency department settings. Given evidence that homeless people make disproportionate use of such services,22,23 including these settings may have identified additional veterans experiencing housing instability. Second, only one-third of the subgroup of veterans eligible to do so completed a rescreen, and they were not representative of all veterans with an initial positive screen who were eligible for a rescreen. Consequently, we could not determine whether those who did not complete a rescreen experienced rates of housing instability that were comparable with those who did complete a rescreen. Differences in the characteristics of these two groups suggest that their rates of continued housing instability would likely differ; however, it is difficult to speculate as to the direction of the difference. Because completion of a rescreen is contingent on accessing VHA health-care services, it is possible that veterans who did complete a rescreen represent a group with more pressing health-care needs and may be at an elevated risk for homelessness. Future research could address this limitation by locating a random sample of veterans who do not complete a rescreen and administering the HSCR to them in an alternative setting.

CONCLUSION

Ongoing efforts to prevent and end homelessness among veterans have made meaningful progress in recent years. As part of these efforts, the HSCR represents an important mechanism for identifying veterans who are experiencing homelessness or risk of homelessness. Findings from this study that only a small proportion of veterans responding to the HSCR experience persistent housing instability underscore both the importance and feasibility of increased and targeted engagement of such veterans with needed services and supports.

REFERENCES

- 1.Interagency Council on Homelessness (US) Washington: Interagency Council on Homelessness; 2010. Opening doors: the federal strategic plan to prevent and end homelessness. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Veterans Affairs (US) Washington: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014. Supportive Services for Veteran Families program: program guide. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Housing and Urban Development (US) Washington: HUD; 2013. The 2013 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to Congress: part 1: point-in-time estimates of homelessness. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrne T, Montgomery AE, Treglia D, Roberts CB, Culhane DP. Health services use among veterans using U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and mainstream homeless services. World Med Health Policy. 2013;5:347–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montgomery AE, Fargo JD, Byrne TH, Kane VR, Culhane DP. Universal screening for homelessness and risk for homelessness in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S210–1. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Housing and Urban Development (US) Washington: HUD; 2008. The third annual homeless assessment report to Congress. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montgomery AE, Fargo JD, Kane V, Culhane DP. Development and validation of an instrument to assess imminent risk of homelessness among veterans. Public Health Rep. 2014;129:428–36. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fihn SD, Francis J, Clancy C, Nielson C, Nelson K, Rumsfeld J, et al. Insights from advanced analytics at the Veterans Health Administration. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1203–11. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Veterans Affairs (US) Priority groups [cited 2013 Jul 9] Available from: URL: http://www.va.gov/healthbenefits/resources/priority_groups.asp.

- 10.Census Bureau (US) Geographic terms and concepts—census divisions and census regions [cited 2014 Jun 14] Available from: URL: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html.

- 11.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.2. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Center for Health Statistics (US) Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; 1980. International classification of diseases, ninth revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner LA, Ignacio RV, Blow FC. Suicide and traumatic brain injury among individuals seeking Veterans Health Administration services. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2011;26:257–64. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31821fdb6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linzer DA, Lewis JB. poLCA: an R package for polytomous variable latent class analysis. J Stat Softw. 2011;42:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuhn R, Culhane DP. Applying cluster analysis to test a typology of homelessness by pattern of shelter utilization: results from the analysis of administrative data. Am J Community Psychol. 1998;26:207–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1022176402357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez TE, Burt MR. Impact of permanent supportive housing on the use of acute care health services by homeless adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:992–9. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perlman J, Parvensky J. Denver: Colorado Coalition for the Homeless; 2006. Denver Housing First Collaborative: cost benefit analysis and program outcomes report. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, Atkins DC, Burlingham B, Lonczak HS, et al. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA. 2009;301:1349–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poulin SR, Maguire M, Metraux S, Culhane DP. Service use and costs for persons experiencing chronic homelessness in Philadelphia: a population-based study. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:1093–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaughlin TC. Using common themes: cost-effectiveness of permanent supported housing for people with mental illness. Res Soc Work Pract. 2011;21:404–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:778–84. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salit SA, Kuhn EM, Hartz AJ, Vu JM, Mosso AL. Hospitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1734–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806113382406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]