Abstract

Background and study aims: Colonoscopy with inhaled methoxyflurane (Penthrox) is well tolerated in unselected subjects and is not associated with respiratory depression. The aim of this prospective study was to compare the feasibility, safety, and post-procedural outcomes of portable methoxyflurane used as an analgesic agent during colonoscopy with those of anesthesia-assisted deep sedation (AADS) in subjects with morbid obesity and/or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Patients and methods: The outcomes of 140 patients with morbid obesity/OSA who underwent colonoscopy with either Penthrox inhalation (n = 85; 46 men, 39 women; mean age 57.2 ± 1.1 years) or AADS (n = 55; 27 men, 28 women; mean age, 54.9 ± 1.1 years) were prospectively assessed.

Results: All Penthrox-assisted colonoscopies were successful, without any requirement for additional intravenous sedation. Compared with AADS, Penthrox was associated with a shorter total procedural time (24 ± 1 vs. 52 ± 1 minutes, P < 0.001), a lower incidence of hypotension (3 /85 vs. 23 /55, P < 0.001), and a lower incidence of respiratory desaturation (0 /85 vs. 14 /55, P < 0.001). The patients in the Penthrox group recovered more rapidly and were discharged much earlier than those in the AADS group (27 ± 2 vs. 97 ± 5 minutes, P < 0.0001). Of those who underwent colonoscopy with Penthrox, 90 % were willing to receive Penthrox again for colonoscopy. More importantly, of the patients who underwent colonoscopy with Penthrox and had had AADS for previous colonoscopy, 82 % (28 /34) preferred to receive Penthrox for future colonoscopies. Penthrox-assisted colonoscopy cost significantly less than colonoscopy with AADS ($ 332 vs. $ 725, P < 0.001), with a cost saving of approximately $ 400 for each additional complication avoided.

Conclusions: Compared with AADS, Penthrox is highly feasible and safe in patients with morbid obesity/OSA undergoing colonoscopy and is associated with fewer cardiorespiratory complications. Because of the advantages of this approach in regard to procedural time, recovery time, and cost benefit in comparison with AADS, further evaluation in a randomized trial is warranted.

Introduction

Colonoscopy is the gold standard technique in the investigation of colonic diseases, especially for the prevention and detection of colorectal neoplasia 1 2. In most Western countries, the procedure is performed with the patient under conscious sedation induced with a combination of fentanyl and midazolam 2 3 4 5 6, administered by the endoscopist. The major risks of conscious sedation are respiratory depression, cardiorespiratory arrest, and a prolonged recovery time 3 5. Predisposing factors that can substantially increase the risk for cardiorespiratory adverse events after sedation are patient co-morbidities, particularly morbid obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 35 kg/m2), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and cardiorespiratory disease 3 5. Given that the risk for cardiorespiratory complications associated with conventional sedation administered by the colonoscopist is substantially high in these patients, it is recommended that the patients be assessed and the sedation be administered during colonoscopy by a dedicated anesthesiologist 3. In most centers in Australia, including our hospital, colonoscopy in these high risk patients is performed in patients on anesthesia-assisted lists; the level of sedation is often deep, achieved mainly with propofol with or without small doses of benzodiazepines and opioid. On infrequent occasions, general anesthesia with airway intubation is required to ensure airway protection during the procedure.

Recently, our group reported the successful use of portable inhaled methoxyflurane (Penthrox; Medical Developments International, Springvale, Victoria, Australia); 3 mL per inhaler) as a form of patient-controlled analgesia for colonoscopy in unselected, medically fit subjects. In this randomized trial 7, the colonoscopic outcomes as well as the pain and anxiety scores of patients who received Penthrox inhalation were comparable with the scores of those who received conventional sedation. Furthermore, it was noted that respiratory depression did not occur in the Penthrox group, whereas it did occur in the sedation group (0 vs. 4 %, P < 0.05) 7.

Methoxyflurane is a volatile anesthetic gas that exhibits uniquely powerful analgesic and anxiolytic effects at well below full anesthetic doses. Its use in general anesthesia, however, was discontinued in the early 1970 s 8 9 because of issues with nephrotoxicity. The drug was subsequently modified to be administered via a portable inhaler and used as an analgesic in the prehospital setting. The dose is limited to 3 mL per inhaler, which is well below the doses associated with renal injury. It has been used in more than 5 million outpatients with an excellent safety profile 10 11. Given the history of possible nephrotoxicity 8 9, it is recommended that the drug not be used in conjunction with other nephrotoxic drugs, such as aminoglycosides and tetracyclines.

Because inhalation is the route of administration of methoxyflurane, the need for an intravenous cannula is avoided, and therefore portable Penthrox has been widely used in the Australasian community by ambulance services in the prehospital setting to relieve the pain of limb and musculoskeletal injuries, chest and abdominal pain, and the pain of back and spinal injuries 10 12 13 14. The maximum recommended dose is 6 mL (2 inhalers) per day or 15 mL (5 inhalers) per week because of the risk for cumulative dose-related nephrotoxicity 10. The amount of drug administered is controlled by the patient via the frequency and depth of inhalation. The onset of action is rapid and can be noticed after 3 to 6 breaths. Each inhaler (3 mL) provides analgesia for approximately 30 minutes 10. Given that inhaled Penthrox causes no respiratory depression, we hypothesized that it might be an attractive alternative approach, in terms of feasibility and safety, to analgesia during colonoscopy in patients at high risk for respiratory depression. The aim of this prospective study was to compare the feasibility, safety, and impact on post-procedural care of Penthrox with those of anesthesia-assisted deep sedation (AADS) for analgesia during colonoscopy in subjects with morbid obesity and/or OSA.

Patients and methods

Subjects

All subjects with morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) and/or OSA who were referred to the tertiary endoscopic center of the Royal Adelaide Hospital for colonoscopy between June 2013 and June 2014 were included. Inclusion criteria were age 18 to 75 years, the ability to give informed consent, and the ability to understand adequately the use of the Penthrox Inhaler. All subjects underwent screening blood tests to check liver and renal function and were excluded if any of the results were abnormal. Exclusion criteria were the following: (i) known history of liver or renal disease, (ii) hypersensitivity to fluorinated agents, (iii) previous head injury, (iv) difficulty in following instructions (including language barrier), (v) concurrent use of any potentially nephrotoxic drugs (e. g., aminoglycosides or tetracyclines), and (vi) a personal or a family history of malignant hyperthermia.

A subject was withdrawn from the study if an adverse event occurred, the subject wished to withdraw, or the presence of significant pain made it necessary for the subject to request extra analgesia (fentanyl) and/or sedation (midazolam). The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Royal Adelaide Hospital, and written consent was obtained from all patients. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Study protocol

Patients with morbid obesity/OSA who were referred to our unit for colonoscopy between June 2013 and June 2014 were invited to participate in the study and were given the choice of either AADS or sedation with Penthrox inhalation. The analgesic/sedative approach for the colonoscopy was determined by the patient’s preference. To minimize technical variability, colonoscopies were performed only by a consultant gastroenterologist. All colonoscopies were performed with standard technique and carbon dioxide insufflation. Procedures were deemed complete if the cecum or terminal ileum was reached. For those who underwent colonoscopy with Penthrox inhalation, liver and renal function tests were repeated 1 month after the procedure.

After a subject had agreed to participate in the study, his or her levels of pain and anxiety were assessed in the waiting room before colonoscopy with the visual analogue scale (VAS) 7 15 and the Spielberger state-trait anxiety inventory, form Y (STAI Y-1) 7 16 17, respectively. Intravenous access was implemented only in subjects receiving AADS, not those receiving Penthrox. Throughout the procedure, the patient's vital signs, oxygen saturation, and hemodynamics were monitored closely and recorded every 3 minutes by a registered nurse, as were signs of excessive sedation, such as drowsiness, pallor, and unresponsiveness. Continuous supplementary oxygen was given only to subjects who received AADS, not those who received Penthrox. Hypotension was defined as a reduction in systolic blood pressure to below 80 % of baseline and/or below 100 mmHg 7 18. A heart rate over 100 beats per minute was defined as tachycardia. Respiratory depression was defined as the need for a high flow oxygen supply (8 – 10 L) because of oxygen desaturation to below 90 % (SpO2 < 90 %) that continued for more than 20 seconds 7 19. Patients in both groups were encouraged to increase their respiration rate when oxygen desaturation occurred.

Details of the colonoscopy procedure, such as duration, time to reach the cecum, need for endoscopic therapy (i. e., polypectomy, argon plasma coagulation), and the occurrence of complications or adverse events, were recorded. The endoscopist was also asked to complete a questionnaire to assess each patient’s levels of pain, anxiety, and cooperation as well the level of technical difficulty related to the colonoscopy. In recovery, the patient’s vital signs, alertness, mental state, and abdominal symptoms were monitored. Once patients were alert and able to obey commands appropriately, they were allowed to sit up in bed and resume oral intake. At this time, the patients were asked to complete a questionnaire to assess their current levels of pain and anxiety, and to assess retrospectively their pain and anxiety during the colonoscopy. The patients were then assessed for their ability to be discharged home. They were asked to report any adverse events occurring up to 30 days after study participation. The research nurse contacted all patients at 24 to 48 hours and at 30 days after the colonoscopy to check for the occurrence of any adverse events related to either the drugs or the colonoscopy.

Anethesia-assisted deep sedation

AADS was provided by the anesthesia team, which consisted of a qualified anesthesiologist and an anesthesia nurse. Depending on the anesthesiologist's preference, a small intravenous bolus injection of opioid (fentanyl or remifentanil [Ultiva; Bioniche Pharma]) and midazolam was often given at the initiation of sedation. Thereafter, an initial bolus of propofol (0.5 mg/kg of body weight) was given intravenously. Sedation was maintained with repeated doses of 10 to 20 mg of propofol or as an infusion based on the patient’s body weight. The goal was deep sedation, based on American Society of Anesthesiologists levels and the Observer's Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Scale 20, on which a purposeful response to a painful stimulus (e. g., a trapezius squeeze) but failure to respond to verbal or light tactile stimuli indicates deep sedation.

Penthrox inhalation

With specific instruction from a dedicated research nurse, the subject was asked to inhale slowly and gently through the Penthrox Inhaler for approximately 2 minutes to become accustomed to its sweet smell. Once the colonoscopy had started, the subject was encouraged to inhale more deeply to optimize drug delivery and obtain sufficient analgesia. In instances when Penthrox did not provide sufficient analgesia or at the patient’s request, the procedure was terminated early and rescheduled to be done with an AADS approach.

Measured outcomes

Primary end points were (i) the rate of adverse events and (ii) the recovery time. Given that the discharge of patients from endoscopy units is often prolonged by issues related to delayed pickup, need for transportation, and other nonmedical issues, both time to “actual discharge” and time to “ready for discharge” were recorded. Time to “ready for discharge” was defined as the time until the caring nurses and physician deemed it to be “medically safe” for the patient to leave the endoscopy unit, whereas time to “actual discharge” was the time until the patient left the endoscopy unit.

Secondary end points were (i) the successfully completed colonoscopy rate, (ii) the pain and anxiety scores during colonoscopy, (iii) the polyp detection rate, (iv) the total colonoscopy procedural time, (v) changes in renal and liver function test results, (vi) cost-effectiveness, and (vii) patient satisfaction.

Cost analysis

The cost analysis of each colonoscopy for patients in both groups was undertaken by a professional health economist, who used data related to the cost of the consumables, drugs, and labor required to perform a colonoscopy as well as the time taken to complete the colonoscopy by each approach. Specifically, the labor cost per patient was estimated by dividing the total cost of all staff involved in operating the unit for a typical day by the estimated number of colonoscopies that could be undertaken in the morning and afternoon sessions with either Penthrox or AADS.

Data analysis

Based on our previous study 7, power calculation with a two-sided significance level of 0.05 and a power of 90 % was performed, and a sample size of at least 50 subjects in each arm was required to demonstrate the differences between the outcomes of the two approaches. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Fisher’s exact test was used for the comparison of categorical data and independent Student’s t test for continuous data. Analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 6 statistical software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA). A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Over 12 months, 140 high risk subjects with morbid obesity and/or OSA were recruited, of whom 85 (61 %) underwent colonoscopy with the Penthrox Inhaler and 55 (39 %) with AADS. The groups did not differ in gender, BMI, proportion of patients with OSA, pre-colonoscopy pain and anxiety scores, colonoscopist perception of patient anxiety level, and indications for colonoscopy (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison between demographics, initial pain and anxiety scores, sedative doses, and procedural indications of patients who received anesthesia-assisted deep sedation (AADS) and those of patients who received Penthrox analgesia during colonoscopy.

| AADS (n = 55) | Penthrox (n = 85) | P value | |

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 54.9 ± 1.1 | 57.2 ± 1.1 | 0.68 |

| Male-to-female ratio | 27:28 | 46:39 | 0.35 |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD, kg/m2 | 37.8 ± 0.5 | 40.2 ± 0.9 | 0.45 |

| Patients with OSA, n (%) | 33 (60) | 41 (48) | 0.36 |

| VAS pain score (0 – 10) before colonoscopy, mean ± SD | 0.52 ± 0.13 | 0.46 ± 0.10 | 0.84 |

| STAI-Y anxiety score, mean ± SD Before colonoscopy Total score Nervousness score After colonoscopy Total score Nervousness score |

45.7 ± 0.9 15.8 ± 0.5 46.9 ± 0.9 15.2 ± 0.5 |

46.1 ± 0.6 14.9 ± 0.5 48.0 ± 0.8 15.3 ± 0.5 |

0.86 0.79 0.48 0.96 |

| Colonoscopist's perception of patient’s anxiety state (VAS), mean ± SD; 0, very calm; 100, most anxious | 60 ± 3 | 53 ± 3 | 0.24 |

| Indications for colonoscopy, n Polyp surveillance Bowel cancer screening (including positive FOBT) Rectal bleeding Abdominal pain IBD-related Diverticular disease-related Investigation of diarrhea Anemia, including iron deficiency anemia Unexplained weight loss |

14 10 7 3 8 2 5 4 2 |

22 28 12 5 6 3 2 5 2 |

0.58 0.87 0.82 0.74 0.69 0.90 0.68 0.59 0.47 |

SD, standard deviation; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; STAI-Y, state-trait anxiety inventory, form Y; VAS, visual analogue scale; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

All colonoscopies with Penthrox inhalation were successful with the use of only 1 inhaler (i. e., 3 mL of methoxyflurane) and did not require any additional administration of intravenous midazolam, fentanyl, fluid therapy, or oxygen supplementation. None of the Penthrox-assisted colonoscopies was discontinued prematurely because of procedural discomfort. In contrast, all the subjects with AADS received intravenous fluid and oxygen therapy during and after colonoscopy (Table 2). In the patients who had colonoscopy with AADS, 286 ± 19 mg of intravenous propofol was used over a mean procedural time of 25.9 ± 1.7 minutes, with the additional use of midazolam in 44 %, fentanyl in 60 %, and remifentanil in 12 % of subjects.

Table 2. Comparison of procedural performance characteristics and adverse events in patients who received anesthesia-assisted deep sedation (AADS) and those who received Penthrox analgesia for colonoscopy.

|

AADS

(n = 55) |

Penthrox (n = 85) | P value | |

| In-room preparation time, mean ± SD, min | 16.5 ± 1.8 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | < 0.01 |

| Cecal arrival time, mean ± SD, min | 11.6 ± 1.0 | 8.8 ± 0.5 | < 0.01 |

| Total colonoscopy time, mean ± SD, min | 25.9 ± 1.7 | 18.4 ± 0.9 | < 0.01 |

| Total in-room time, mean ± SD, min | 51.6 ± 1.3 | 23.9 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| Patients with polypectomy, n (%) | 23 (44) | 46 (54) | 0.18 |

| Patients with incomplete colonoscopy, n (%) due to severe sigmoid diverticulosis due to significant looping due to poor preparation |

3 (5) 1 1 1 |

1 (1) 0 1 0 |

0.39 |

| Patients requiring intravenous fluid therapy during and after colonoscopy, n (%) | 55 (100) | 01 | < 0.001 |

| Patients requiring oxygen supplementation to maintain SaO2 > 90 %, n (%) | 55 (100) | 01 | < 0.001 |

SD, standard deviation.

P < 0.01 vs. AADS.

Procedural success

Although there was no difference between the cecal intubation rates of the two groups (Penthrox vs. AASD: 99 % vs. 95 %, P = 0.30), the in-room preparation time (4.8 ± 0.2 vs. 16.5 ± 1.8 minutes, P < 0.01), cecal arrival time (8.8 ± 0.5 vs. 11.6 ± 1.0 minutes, P < 0.01), and total colonoscopy time (18.4 ± 0.9 vs. 25.9 ± 1.7 minutes, P < 0.01) were significantly shorter in the Penthrox group than in the AADS group. There were no differences between the rates of polyp detection and polypectomy in the two groups (Table 2). In 1 of the 4 colonoscopies that failed to reach the cecum, failure was related to poor pain relief; the reasons for failure are summarized in Table 2. Of these patients, 3 had subsequent computed tomographic colonography (2 AADS and 1 Penthrox) and 1 had a second colonoscopy after extended bowel cleansing.

Adverse events and impact on liver and renal function

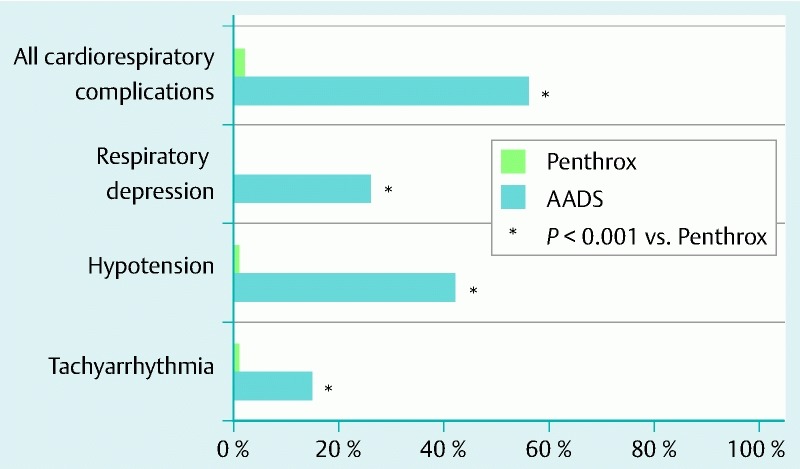

Although intravenous fluid therapy and oxygen supplementation were given to all patients who had AADS, there were more intraprocedural events of hypotension (42 % vs. 1 %), respiratory depression (26 % vs. 0 %), and tachyarrhythmia (15 % vs. 1 %) in the patients who received AADS than in those who received Penthrox inhalation (Fig. 1). Overall, intraprocedural cardiorespiratory adverse events were substantially more frequent in the AADS group than in the Penthrox group (56 % vs. 2 %, P < 0.001). At telephone follow-up 24 hours and 30 days after colonoscopy, no patient reported being readmitted or was found to have been readmitted to the hospital because of abnormal renal or liver function test results indicating nephrotoxicity or hepatotoxicity. Penthrox inhalation did not result in any increases in serum levels of creatinine, liver enzymes, or bilirubin after 1 month (Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Differences between the cardiorespiratory complication rates of patients who had colonoscopy with anesthesia-assisted deep sedation and those of patients who had colonoscopy with Penthrox analgesia.

Table 3. Comparison of parameters of renal and liver function before and 1 month after Penthrox inhalation for colonoscopy.

| Before Penthrox | After Penthrox | P value | |

| Renal function Creatinine, mean ± SD, µmol/L (NR 50 – 120) |

70.5 ± 2.7 | 73.1 ± 3.3 | 0.77 |

| Liver function Bilirubin , mean ± SD, µmol/L (NR 2 – 24) GGT, mean ± SD, U/L (NR < 60) ALP, mean ± SD, U/L (NR 30 – 110) AST, mean ± SD, U/L (NR < 45) ALT, mean ± SD, U/L (NR < 55) |

10.5 ± 1.0 49.7 ± 4.5 83.9 ± 4.0 27.2 ± 2.5 31.5 ± 4.2 |

10.0 ± 0.9 46.8 ± 6.1 86.6 ± 4.5 25.0 ± 1.3 27.5 ±2.2 |

0.89 0.62 0.43 0.58 0.28 |

SD, standard deviation; NR, normal range; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; ALP, alpha-fetoprotein; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Recovery and discharge time

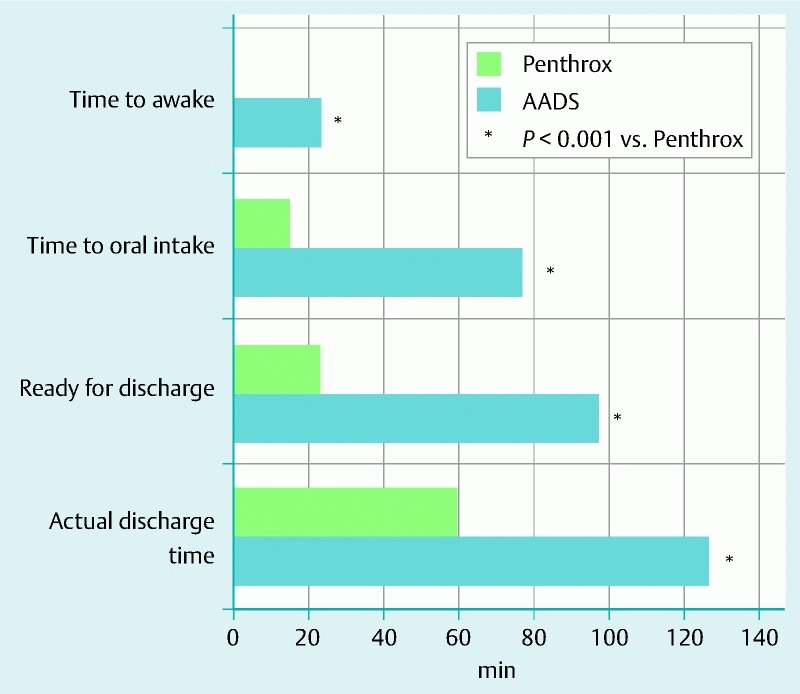

The patients who received Penthrox had significantly shorter times to being awake, oral intake, readiness for discharge, and actual discharge than did those who received AADS (Fig. 2). Overall, the patients who had Penthrox were ready to be discharged at least 60 minutes earlier than those who had AADS.

Fig. 2.

Differences between the recovery and discharge times of patients who received anesthesia-assisted deep sedation (AADS) and those of patients who received Penthrox analgesia for colonoscopy.

Cost analysis

In the morbidly obese patients, the cost of colonoscopy with Penthrox inhalation was less than half that of colonoscopy with AADS ($ 331.79 AUD vs. $ 725.41 AUD). The significantly shorter procedural time with Penthrox was estimated to have allowed more procedures to be performed in patients on a 4-hour list (8 vs. 4 cases, P < 0.05). Based on these outcomes, as well as the lower incidence of adverse events, the use of Penthrox for colonoscopy was found to be a “superior” strategy for these high risk subjects, with a cost saving of approximately $ 400 AUD for each additional complication avoided.

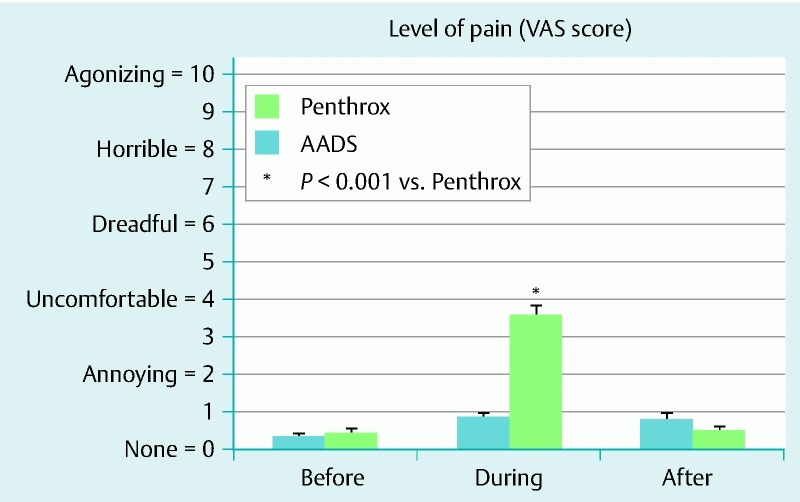

Patient satisfaction, pain, and state-trait anxiety inventory anxiety scores

Although there was no difference between the satisfaction scores of the two groups (AADS vs. Penthrox: 94 ± 6 vs. 98 ± 5; P = 0.76), 28 of 34 Penthrox patients (82 %) who had undergone a previous colonoscopy with AADS preferred Penthrox over AADS. The patients who had completed colonoscopy with Penthrox alone reported that the inhaler was easy to use, provided adequate analgesia, and allowed them to have good recall of the procedural findings, and 90 % were willing to receive Penthrox again for colonoscopy. Although the patients who received Penthrox had a higher pain score during colonoscopy (3.6 ± 0.2 vs. 0.9 ± 0.1, P < 0.001; Fig. 3), the pain was perceived as tolerable and short-lasting. There were no differences between the total STAI-Y anxiety (“nervousness”) scores of the two groups before and after colonoscopy (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Differences between the visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores before, during, and after colonoscopy of patients who had anesthesia-assisted deep sedation (AADS) and those of patients who had Penthrox analgesia for colonoscopy.

Discussion

This is the first study to show that patient-controlled analgesia with inhaled methoxyflurane as a method of relieving discomfort during colonoscopy is feasible, safe, and as effective as AADS in subjects who have morbid obesity with or without obstructive sleep apnea. Although ours is not a randomized study, this new approach to analgesia during colonoscopy has demonstrated several major advantages over conventional AADS in these patients, including the following: (i) a better safety profile with significantly fewer cardiorespiratory complications, (ii) significantly shorter preparation and procedural times with similar cecal intubation and polypectomy rates, (iii) a significantly shorter recovery time with earlier discharge, (iv) substantially greater cost-effectiveness with potentially shorter waiting lists, and (v) good patient satisfaction overall, with more than 90 % patients willing to undergo further colonoscopy with inhaled Penthrox. These findings suggest that in subjects who are morbidly obese or have OSA without liver or renal disease, colonoscopy with Penthrox inhalation is a safe and cost-effective alternative, with great potential to improve workflow and optimize the health economics of endoscopy units, especially those with long waiting lists. More importantly, when given the option, a majority of these high risk subjects (85/140, or 61 %) were willing to use Penthrox inhalation for colonoscopy, and 82 % patients who had had AADS for previous colonoscopies preferred to have Penthrox for their future colonoscopies, indicating that the clinical application of Penthrox analgesia for colonoscopy in this group is highly feasible.

Because of concerns about the potential impact of methoxyflurane on undiagnosed fatty liver disease or diabetic nephropathy, which are common co-morbidities of morbid obesity, patients were carefully screened and monitored for both renal and liver function in the current study, and these were not altered by Penthrox inhalation (3 mL in the current study; Table 3). It is important to recognize that the toxicity of methoxylflurane is dose-dependent, and the reported nephrotoxic and hepatotoxic effects are observed only with the much higher doses used for general anesthesia 8 9. As demonstrated in our previous trial 7, provided that the subject has normal liver and renal function or no known liver or renal disease, Penthrox inhalation within the recommended dosage is safe, even in patients with morbid obesity and OSA.

Although the potential risks associated with occupational exposure to volatile methoxyflurane used routinely in clinical endoscopy has always been a concern for the staff, no occupational adverse effects have been reported from the 5 million units used since 1975 (60 % in the ambulance setting) at the recommended dose 10 11. Even in the small air space of an ambulance, the exposure to methoxyflurane over an 8-hour work day is extremely small (ranging from 0.1 to 0.6 ppm) 11. In rats, prolonged exposure to a concentration of 50 ppm is required to cause any potential hepatotoxicity or nephrotoxicity 21. Given that endoscopy rooms are much larger (4 to 5 times the size of an ambulance) and have better ventilation systems, it is expected that occupational exposure to Penthrox in an endoscopy unit would be substantially smaller than that in a paramedical setting. Furthermore, unlike one in an ambulance setting, a Penthrox Inhaler in an endoscopy suite is always used with an activated carbon chamber, which can further reduce the concentration of exhaled methoxyflurane. Methoxyflurane has a characteristically fruity odor, and any inadvertent leakage, therefore, can be detected easily and rapidly.

It is important to recognize that the incidence of cardiorespiratory complications is substantially lower in patients undergoing Penthrox-assisted colonoscopy than in those receiving AADS, with essentially no risk for respiratory depression. This is most likely related to the minimal, if any, sedative effect of Penthrox inhalation, giving it a safety profile that is highly desirable for subjects who are at high risk for respiratory complications during sedation of any level. Similarly, it is likely that propofol was the agent that caused the greater incidence of hypotension and related arrhthymias in the AADS group. Furthermore, the nonsedative property of Penthrox, in contrast to AADS, enables subjects to be awake and use the drug at their discretion, have a better recall of the colonoscopy findings, and recover at an “ultrafast” pace. This may explain the preference for Penthrox over AADS for future colonoscopy in the 82 % of patients who had prior colonoscopy with AADS.

The substantially better cost-effectiveness of Penthrox inhalation than of AADS for colonoscopy in the current study has major health economic implications, given the current demand for colonoscopy for bowel cancer screening and surveillance in an epidemically obese population. The significantly shorter procedural time with Penthrox colonoscopy not only would allow more procedures to be performed in a list or over a year but also would also avoid the need for anesthesia-assisted lists, reducing the waiting time for colonoscopy in these high risk patients. This advantage is particularly relevant for endoscopy units where the anesthesia service resources for endoscopy are limited and often conserved for interventional endoscopy lists. At present in these centers, the waiting lists for diagnostic upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures to be performed with AADS are usually longer than the lists for procedures to be performed with conscious sedation (approximately 6 – 9 vs. 3 months). The waiting time can be further prolonged for these subjects because priority is often given to patients undergoing interventional procedures, such as endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, and balloon enteroscopy. Therefore, provided that liver and renal function is normal, the issue of long waiting lists for these patients can be overcome with the use of Penthrox inhalation.

Potential weaknesses of the current study are its lack of randomization, modest sample size, and selection bias toward “healthy” morbidly obese patients without liver or renal disease. Before a large randomized trial in these high risk subjects is considered, it was deemed important to perform a pilot study to ensure that Penthrox-assisted colonoscopy is feasible and safe in these patients. Although the assessment of patients during recovery by the nursing staff may have been influenced by the fact that the nurses were not blinded to the type of analgesia or sedation used, we had a standardized protocol for assessing and recording time to awake, time to oral intake, time to readiness for discharge, and time to actual discharge. The assessments were based on alertness and vital signs, which are very objective.

Although portable Penthrox inhalation is currently not available anywhere in the world apart from Australasia, applications for its use in Europe and Asia are currently in progress. Given that nitrous oxide is more widely available and has been shown to have comparable analgesic properties in dental procedures 22, a comparison of outcomes with Penthrox and with nitrous oxide in colonoscopy would be clinically relevant and warranted. Although there are no available data on the use of Penthrox inhalation for colonic endoscopic mucosal resection or dissection, it is likely to be feasible, and further evaluation is warranted given that these procedures do not normally cause significant discomfort. Similarly, the application of this modality of analgesia during other upper gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures has not been explored.

Conclusions

In patients who have morbid obesity and/or sleep apnea, colonoscopy with patient-controlled inhaled Penthrox is feasible and safe, with a 99 % procedural success rate, high patient satisfaction scores, no respiratory complications, significantly shorter procedural and recovery times, and greater cost-effectiveness. The findings indicate that colonoscopy with Penthrox analgesia in these high risk subjects may facilitate workflow, shorten waiting lists, and improve cost-effectiveness in busy endoscopy units, and the benefits warrant further evaluation in a large randomized trial.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None

References

- 1.Bourke M J. Making every colonoscopy count: ensuring quality in endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:S43–S50. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.06070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jover R, Herraiz M, Alarcon O. et al. Clinical practice guidelines: quality of colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. Endoscopy. 2012;44:444–451. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1306690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen L B. Sedation issues in quality colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010;20:615–627. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayee B, Dunn J, Loganayagam A. et al. Midazolam with meperidine or fentanyl for colonoscopy: results of a randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:681–687. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannert C, Reinhart K, Dunkler D. et al. Sedation in screening colonoscopy: impact on quality indicators and complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1837–1848. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ladas S D, Satake Y, Mostafa I. et al. Sedation practices for gastrointestinal endoscopy in Europe, North America, Asia, Africa and Australia. Digestion. 2010;82:74–76. doi: 10.1159/000285248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen N Q, Toscano L, Lawrence M. et al. Patient-controlled analgesia with inhaled methoxyflurane versus conventional endoscopist-provided sedation for colonoscopy: a randomized multicenter trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:892–901. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toomath R J, Morrison R B. Renal failure following methoxyflurane analgesia. N Z Med J. 1987;100:707–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubinger D, Davidson J T, Melmed R N. Hepatitis following the use of methoxyflurane in obstetric analgesia. Anesthesiology. 1975;43:593–595. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197511000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grindlay J, Babl F E. Review article: Efficacy and safety of methoxyflurane analgesia in the emergency department and prehospital setting. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21:4–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2009.01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Australian Government, Department of Health, Therapeutic Goods Administration Medicines Safety UpdateVolume 5Number 2, April 2014, Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/publication-issue/medicines-safety-update-volume-5-number-2-april-2014. Accessed May 14, 20152014

- 12.Bendall J C, Simpson P M, Middleton P M. Prehospital analgesia in New South Wales, Australia. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2011;26:422–426. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X12000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston S, Wilkes G J, Thompson J A. et al. Inhaled methoxyflurane and intranasal fentanyl for prehospital management of visceral pain in an Australian ambulance service. Emerg Med J. 2011;28:57–63. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.078717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buntine P, Thom O, Babl F. et al. Prehospital analgesia in adults using inhaled methoxyflurane. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19:509–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen P J, Li C H, Huang T Y. et al. Carbon dioxide insufflation does not reduce pain scores during colonoscope insertion in unsedated patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwata N, Mishima N, Shimizu T. et al. Positive and negative affect in the factor structure of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Japanese workers. Psychol Rep. 1998;82:651–656. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.2.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spielberger C D, Vagg P R. Psychometric properties of the STAI: a reply to Ramanaiah, Franzen, and Schill. J Pers Assess. 1984;48:95–97. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4801_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dahlgren G, Irestedt L. The definition of hypotension affects its incidence. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:907–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2010.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Kajiyama M. et al. Safety and effectiveness of propofol sedation during and after outpatient colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3420–3425. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i26.3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sipe B W, Rex D K, Latinovich D. et al. Propofol versus midazolam/meperidine for outpatient colonoscopy: administration by nurses supervised by endoscopists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:815–825. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.124636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plummer J L, Hall P D, Jenner M A. et al. Hepatic and renal effects of prolonged exposure of rats to 50 p.p.m. methoxyflurane. . Acta Pharmacol Toxicol. 1985;57:176–183. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.1985.57.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdullah W A, Sheta S A, Nooh N S. Inhaled methoxyflurane (Penthrox) sedation for third molar extraction: a comparison to nitrous oxide sedation. Aust Dent J 2011. 2011;56:296–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]