Abstract

The present study examined associations between emotional awareness facets (type clarity, source clarity, negative emotion differentiation, voluntary attention, involuntary attention) and sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, and socioeconomic status (SES)) in a large US sample (N = 919). Path analyses—controlling for variance shared between sociodemographic variables and allowing emotional awareness facets to correlate—demonstrated that (a) age was positively associated with type clarity and source clarity, and inversely associated with involuntary attention; (b) gender was associated with all facets but type clarity, with higher source clarity, negative emotion differentiation, voluntary attention, and involuntary attention reported by women then men; and (c) SES was positively associated with type clarity with a very small effect. These findings extend our understanding of emotional awareness and identify future directions for research to elucidate the causes and consequences of individual differences in emotional awareness.

Keywords: emotional awareness, emotion differentiation, emotional clarity, attention to emotions, age differences, gender differences, socioeconomic status

1. Introduction

Emotional awareness is a multifaceted construct that broadly encompasses how people understand, describe, and attend to their emotional experiences (Bagby, Taylor, & Parker, 1994; Boden & Berenbaum, 2011; Gasper & Clore, 2000; Gohm & Clore, 2000; Palmieri, Boden, & Berenbaum, 2009; Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995). Emotional awareness has multiple broad dimensions, including clarity of emotions (i.e., the degree to which people unambiguously identify, label, and represent their own emotions), emotion differentiation (i.e., the complexity with which people represent the type of emotion they experience), and attention to emotion (i.e., the degree to which people attend to their emotions). These dimensions are facets of several constructs popularized in scientific literature, including emotional intelligence and alexithymia (e.g., Bagby et al., 1994; Gohm, 2003; Gohm & Clore, 2000; Salovey et al., 1995).

Identifying sources of individual variation in emotional awareness will inform theory and research on its potential downstream consequences. For example, numerous researchers have explored how emotional awareness relates to emotion regulation (e.g., Barrett, Gross, Christensen, & Benvenuto, 2001; Boden & Thompson, 2015; Kashdan, Barrett, & McKnight, 2015; Vine & Aldao, 2014). Sociodemographic characteristics are one potential source of individual variation in emotional awareness; associations between emotional awareness and sociodemographic characteristics are not well characterized. Addressing this gap might clarify the contexts within which emotional awareness contributes to adaptive emotion regulation. In this cross-sectional study, we investigated how age, gender, and SES relate to emotional awareness in a large generally representative adult sample of the U.S. Following, we review research on facets of emotional awareness and describe how sociodemographic characteristics may relate to them.

1.1. Emotional Awareness

Recent research has delineated multiple sub-facets of two broad dimensions of emotional awareness: emotional clarity and attention to emotions (Boden & Berenbaum, 2011; Boden & Thompson, 2015; Huang, Berenbaum, & Chow, 2013). Emotional clarity is parsed into type clarity and source clarity (Boden & Berenbaum, 2011). Type clarity represents the extent to which people unambiguously identify, label, and represent the type of emotion experienced (e.g., sadness versus anger). Source clarity represents the extent to which people unambiguously identify, label, and represent the source of their emotional experiences (Boden & Berenbaum, 2011; 2012). For example, greater source clarity reflects an improved ability to understand the source of their distress, whereas greater type clarity reflects an improved ability to understand the particular type of distress they might feel (e.g., sadness, fear). Distinct from emotional clarity is negative emotion differentiation (Boden, Thompson, Dizén, Berenbaum, & Baker, 2013), which captures the complexity with which people identify, distinguish, and label specific negative emotions (e.g., sad, depressed, anxious versus bad; Barrett et al., 2001; Kashdan et al., 2015). In the current study, we examined negative emotion differentiation, which has been shown to uniquely predict psychological well-being (e.g., Barrett et al., 2001; Erbas, Ceulemans, Pe, Koval, & Kuppens, 2014). Attention to emotion is parsed into voluntary attention and involuntary attention (Huang et al., 2013; Boden & Thompson, 2015). Voluntary attention represents the extent to which people purposefully attend to their emotions, and involuntary attention represents the extent to which people attend to their emotions unintentionally (Huang et al., 2013).

1.2. Age

Emotional awareness facets should vary across the lifespan. We presume that older adults have had a greater number and more diverse learning experiences involving emotion. As people age, we posit that they experience more opportunities to “practice” identifying, labeling, and representing the type and source of their emotions. Therefore, we predict that age will be positively associated with type and source clarity. We expect to replicate the finding that emotion differentiation is positively associated with age (e.g., Ready, Carvalho, & Weinberger, 2008). We think that age will be positive associated with negative emotion differentiation because greater differentiation is related to more adaptive psychological and emotional functioning (e.g., Barrett et al., 2001; Kashdan et al., 2015), and growing older has been associated with adaptive patterns of emotional processing (e.g., Blanchard-Fields, 2007; Carstensen, Pasupathi, Mayr, & Nesselroade, 2000). Research on the socioemotional selectivity theory (e.g., Carstensen, 2006; Charles & Carstensen, 2009; Scheibe & Carstensen, 2010) suggests that as people age, they prioritize socially and emotionally meaningful goals and become more selective about the situations and people with whom they associate. They focus more on the emotional aspects of their experience that optimize adaptive outcomes (e.g., Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999). This increased control over how older individuals attend to their emotional experiences suggests two things. First, they attend more to emotions that are consistent with their social and emotional goals. Second, they do not generally attend to emotions that are inconsistent with these goals. In line with this, we predict that older age will be positively associated with voluntary attention to emotions and inversely associated with involuntary attention to emotions.

1.3. Gender

Extant research has demonstrated that emotional experience differs by gender, but that many of these differences are driven by cultural factors (Brody & Hall, 2008). For example, women in Western cultures are stereotyped as being more emotionally expressive, emotionally skilled, and emotionally intense than men (see Brody & Hall, 2008). In fact, research has found that women attend more to their emotions than men (Boden et al., 2013; Gasper & Clore, 2000; Gohm & Clore, 2000). Because stereotypes affect behavior through both conscious and nonconsicous manners (e.g., Hilton & Hippel, 1996), compared to men, woman might attend more to their emotions both voluntarily and involuntarily due to how they were socialized to experience emotion, including the influence of these aforementioned gender stereotypes.

In contrast to attention to emotion, past research indicates that type and source clarity do not vary by gender (Boden, Gala, & Berenbaum, 2013; Gohm, & Clore, 2000; B. Thompson, Waltz, Croyle, & Pepper, 2007; Boden & Berenbaum, 2012). Although the experience of emotions may vary by gender in terms of attention to emotions, the extent to which emotions are unambiguously identified, labeled, and represented (type clarity and source clarity) do not tend to differ. We do not make a specific prediction regarding the association between negative emotion differentiation and gender; no prior studies have examined their association, and relevant theory does not suggest that men or women should differ in negative emotion differentiation.

1.4. Socioeconomic Status

SES reflects social position and status in society; it is a complex construct with multiple sources of influence. The American Psychological Association (APA, 2007) recommends operationalizing SES by including income, occupation, and education. SES might relate to emotional awareness facets of emotional awareness. For example, if emotional awareness contributes to effective navigation of day-to-day life, then we would expect SES to positively relate to some of the facets. Indeed, in a prospective study, Libbrecht, Lievens, Carette, and Côté (2014) demonstrated that higher emotional understanding, which is conceptually related to type and source clarity and negative differentiation, predicted higher levels of interpersonal academic performance (i.e., performance in courses that centered on doctor-patient communication) among medical students. Further, Perera and DiGiacomo (2015) found that during the transition to university, emotional intelligence, which includes aspects akin to type and source clarity and negative emotion differentiation, contributed to academic performance through the engagement in coping strategies. On the other hand, other research on facial expressions of emotions has suggested that lower SES might relate to greater emotional awareness. Compared to people in higher status positions, people in lower status positions are better able to distinguish facial expressions of emotions (Kraus, Côté, & Keltner, 2010); this increased awareness of others’ emotions might extend to increased awareness of one’s own emotions. Therefore, we explore how SES relates to emotional awareness facets in the present study.

1.5. The Present Study

We predicted that older age would be associated with higher type clarity, source clarity, negative emotion differentiation, and voluntary attention and lower involuntary attention; and that gender would not be associated with type clarity or source clarity, but that women would report higher voluntary attention and involuntary attention than would men. Finally, we explore how SES would be related to individual variation in emotional awareness facets without specific predictions.

2. Method

2.1. Participants & Procedure

We recruited an adult sample through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). MTurk provides diverse samples of the U.S. population with data that is similar in quality to convenience samples (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Paolacci & Chandler, 2014). We restricted recruitment to U.S. citizens who were 18 years or older and spoke English as their first language. Of 1022 people who indicated interest in the study, 64 people did not meet inclusion criteria and 103 people did not complete any study items. The final sample was 919 participants.

Once eligibility was established, participants consented to participation and provided demographic characteristics (see Results). For our analyses of gender, we dummy-coded the data (men = 0, and women = 1). Participants completed a negative emotion differentiation task and self-report measures of clarity and attention. We presented measures in a randomized order across participants. We compensated participants 0.50USD, a rate consistent with MTurk surveys of this length.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Emotional awareness

Emotional clarity and attention to emotions were assessed with items recommended by Boden and Thompson (2015), based on the results of a factor analysis of data obtained from the present sample. We assessed type clarity with 13 items from the clarity subscale of the Trait Meta Mood Scale (TMMS; Salovey et al., 1995) and the Difficulty Identifying Feelings subscale of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20; Bagby et al., 1994). Source clarity was assessed with five items from the Sources of Emotions Scale (Boden & Berenbaum, 2012). We assessed voluntary attention with six items from the Attention subscale of the TMMS and two items from the Externally Oriented Thinking subscale of the TAS-20. Involuntary attention was assessed with seven items recommended by Huang, Berenbaum and Chow (2013) and two TMMS items from the Attention subscale. Participants responded to items using a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree). We averaged these scores; higher scores indicated higher levels of each facet. Internal consistencies were as follows: type clarity: α = .92; source clarity: α = .91; voluntary attention: α = .85; involuntary attention: α = .92.

We assessed negative emotion differentiation with a modified version of the negative emotion differentiation task (Erbas et al., 2014). Participants viewed ten standardized emotional photographs (presented individually in randomized order) from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1995), representing a wide range of negative emotions. For each image, participants reported their current experience of ten negative emotions (i.e., fearful, worried, lonely, sad, guilty, ashamed, jealous, embarrassed, angry, disgusted) on a 7-point Likert scale (0=not at all, 6=very much). To compute negative emotion differentiation, we calculated the average intra-class correlation with absolute agreement (ICC 1; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) between the negative emotion words across the image presentations for each participant (e.g., Barrett, 1998; Boden et al., 2013; Kashdan, Ferssizidis, Collins, & Muraven, 2010; Pond et al., 2012; Tugade et al., 2004). We transformed the ICCs using Fisher Z’ transformation (see Boden et al., 2013). To facilitate interpretation, we reverse-coded the transformed ICCs such that higher values represent higher levels of negative emotion differentiation.

2.2.2. SES

Participants reported their household’s annual income in categories ranging from 1 ($0-10,000) to 21 ($500,000 or more). They completed two questions from the Four Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, 1975), which assessed their occupation and highest level of completed education. For occupation, participants provided a free response to “What do you do for a living?” Three extensively trained undergraduate research assistants rated responses with the Hollingshead coding scheme (Hollingshead, 1975), which provides hierarchical ratings from 1 (e.g., farm laborers/menial service workers) to 9 (e.g., higher executives, proprietors of large business, and major professionals). Interrater reliability (Fleiss’ kappa; Fleiss, 1971) was κ = .78. Raters reached consensus for divergent ratings through discussion; consensus ratings were used in the analyses. For education, participants indicated their highest level of completed education, ranging from 1 (i.e., less than seventh grade) to 7 (i.e., graduate/profession training). We computed a SES composite score by taking the mean of standardized values of income, education, and occupation.

3. Results

Demographic information is presented in Table 1. The majority of the sample was female and Caucasian/white, with substantial variation in age. Participants reported an average income equivalent to approximately $50,000. Approximately half of the participants had earned a bachelor’s degree, and the average occupation score was between 5 (clerical/sales jobs, small farm owners) and 6 (technicians and semi-professionals). Consistent with previous research utilizing MTurk (Paolacci & Chandler, 2014), our sample was diverse. Yet it was composed of a greater proportion of women, and was younger, more White/Caucasian, and more educated compared to the general population (US Census Bureau, 2015).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics and descriptive statistics

| Variable | % | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 35.4 | 13.1 | 18 – 79 | |

| Gender (female) | 66.9 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 3.7 | |||

| Biracial/Bicultural | 4.2 | |||

| Black | 7.5 | |||

| Native American | 0.4 | |||

| Native Hawaiian | 0.3 | |||

| White | 83.8 | |||

| Income | 5.2 | 3.3 | 1 – 21 | |

| Occupation | 5.8 | 1.9 | 1 – 9 | |

| Completed Education | ||||

| Partial High School | 1.6 | |||

| High School (or GED) | 15.7 | |||

| Partial College | 31 | |||

| College or University | 34.9 | |||

| Graduate or Professional | 16.8 | |||

| Socioeconomic Status Composite | −.03 | 0.7 | −2.01 – 2.67 | |

| Emotional Awareness Facets | ||||

| Type Clarity | 3.8 | 0.8 | 1.23 – 5 | |

| Source Clarity | 4.0 | 0.9 | 1 – 5 | |

| Negative Emotion Differentiation | 0.5 | 0.5 | −1.65 – 1 | |

| Voluntary Attention | 3.7 | 0.7 | 1.13 – 5 | |

| Involuntary Attention | 3.3 | 0.9 | 1 – 5 |

Note. Socioeconomic Status Composite is composed of the mean of standardized income score, occupation score, and completed education.

We conducted correlation analyses (point-biserial correlations for gender: Pearson correlations for all others) to examine the zero-order relations among emotional awareness facets and sociodemographic variables. As shown in Table 2, due to the large sample size, many of the correlations were statistically significant. Thus, we focus the discussion of these results in terms of the strength of the effect in conjunction with standard rules of thumb (i.e., small = .10, medium/moderate = .30, large = .50; Cohen, 1992). Type and source clarity were positively associated to a large degree and each had a small positive association with negative emotion differentiation. Type and source clarity each had a moderate positive association with voluntary attention and a moderately small negative association with involuntary attention. Negative emotion differentiation had a very small negative association with involuntary attention and a small positive association with voluntary attention. Voluntary attention and involuntary attention were positively associated to a moderately large degree. Age had a small positive association with SES. Age also had a small positive association with type clarity and source clarity and a small negative association with involuntary attention. Gender was moderately associated with voluntary attention, involuntary attention and emotional differentiation, such that women tended to report higher levels of these emotional awareness facets. SES had a very small positive association with type clarity.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations among Sociodemographic Characteristics and Emotional Awareness Facets

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | |||||||

| 2. Gender | .03 | ||||||

| 3. Socioeconomic Status | .10** | −.03 | |||||

| 4. Type Clarity | .25** | .05 | .09** | ||||

| 5. Source Clarity | .17** | .08* | .01 | .69** | |||

| 6. Negative Emotion Differentiation | .08* | .10** | .01 | .21** | .25** | ||

| 7. Voluntary Attention | .04 | .31** | −.06 | .28** | .29** | .12** | |

| 8. Involuntary Attention | −.15** | .20** | −.07* | −.23** | −.23** | −.05 | .45** |

Note. Gender is coded as men = 0, women = 1. Correlation coefficients involving gender are point-biserial. All other coefficients are Pearson.

p < .05

p < .01

Next, we examined the unique relations between sociodemographic characteristics and emotional awareness facets. Using version 7.3 of MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 2014), we conducted a path analysis using a model that specified simultaneous standardized regression coefficient paths from each sociodemographic characteristic (age, gender, SES) to each emotional awareness facet, which accounted for variance shared between sociodemographic variables. We allowed the (1) sociodemographic characteristics to correlate with each other, (2) the residuals of the emotional awareness facets to correlate with each other, and (3) allowed age to be dichotomous while all other variables were continuous. We examined main effect sizes of age, gender, and SES in the path analysis by computing the variance explained (incremental increase in R2) by the inclusion of each of these sociodemographic variables in separate path models. For example, to test the effect of age, age was added to a model that included gender, SES, and all emotional awareness facets. We did the same in separate models for gender and SES. Age incrementally accounted for 11.3% of the variance; gender incrementally accounted for 14.9% of the variance; and SES incrementally accounted for 1% of the variance.

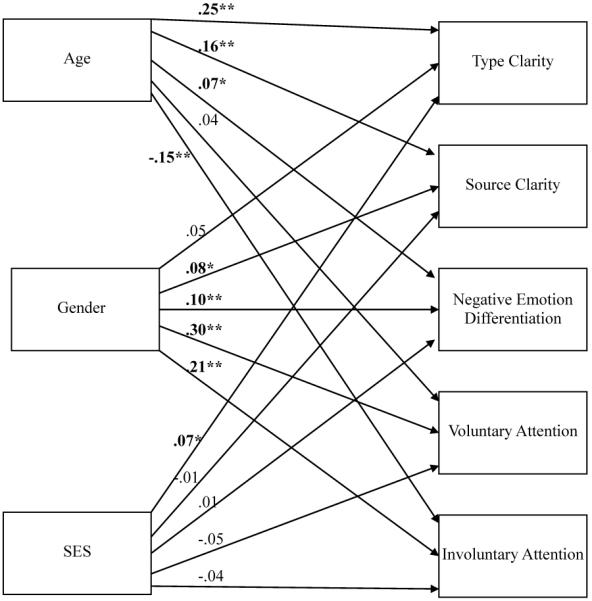

As shown in Figure 1, path analysis results were similar to the zero-order correlation findings. Consistent with our hypotheses, age had a moderate positive association with type clarity, a small positive association with source clarity, and a small negative association with involuntary attention. Inconsistent with our hypotheses, age was not significantly associated with voluntary attention, and the association of age and negative emotion differentiation was only quite small. With regard to gender, as expected, there were gender was unrelated to differences in type clarity; and being female was moderately associated with greater voluntary and involuntary attention than was being male. We also found that gender was associated with negative differentiation, such that women reported slightly higher negative emotion differentiation than did men. Women also reported slightly higher source clarity than did men. Finally, SES only had a very small positive association with type clarity1 but no significant associations with the other four emotional awareness facets.

Figure 1.

Path analysis predicting emotional awareness facets (type clarity, source clarity, negative emotion differentiation, voluntary attention, and involuntary attention) from sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender (men = 0; women = 1), socioeconomic status [SES]). All path coefficients are standardized. To avoid visual clutter, the following correlations are excluded from the figure: Age by Gender = .03, Age by SES = .10**, Gender by SES = −.03, Type Clarity by Source Clarity = .68**, Type Clarity by Negative Emotion Differentiation = .20**, Type Clarity by Voluntary Attention = .28**, Type Clarity by Involuntary Attention = −.21**, Source Clarity by Negative Emotion Differentiation = .24**, Source Clarity by Voluntary Attention = .28**, Source Clarity by Involuntary Attention = −.16**, Negative Emotion Differentiation by Voluntary Attention = .09**, Negative Emotion Differentiation by Involuntary Attention = −.06, Voluntary Attention by Involuntary Attention = .42**.

* p < .05; ** p < .01.

4. Discussion

The current study significantly furthers the scope of the emotional awareness literature. The results demonstrate that sociodemographic factors showed varying associations with emotional awareness facets in a generally representative sample of the U.S. Findings highlight several avenues that will elucidate how social and developmental processes contribute to differences in emotional awareness.

Extending research on the socioemotional selectivity theory (e.g., Scheibe & Carstensen, 2010), age was positively associated with generally adaptive emotional awareness facets, including type clarity and source clarity and a very small effect on negative emotion differentiation. Previous research demonstrates that as individuals age, they prioritize processing material that is consistent with short-term goals and de-emphasize processing negative material (e.g., Löckenhoff & Carstensen, 2004); older participants reporting lower involuntary attention supports this line of research. Perhaps increasingly careful selection of one’s socioemotional environment relates to mastery over attention to emotion. The absence of association between voluntary attention and age might reflect that older adults attend more to positive and less to negative emotions (Reed, Chan, & Mikels, 2014), leading to insignificant associations when valence is not assessed as in the present study. Thus, future research should assess attention to positive and negative emotions separately to clarify their associations with age.

We extended research on gender and emotion (e.g., Brody & Hall, 2008) by demonstrating that women exhibit higher levels of negative emotion differentiation than men, albeit with a small effect. We corroborated extant research that type clarity was not associated with gender (e.g., Boden et al., 2013; Gasper & Clore, 2000; B. Thompson et al., 2007). Inconsistent with our hypotheses, women reported higher levels of source clarity than did men, but with a very small effect. Although there was little association between gender and type clarity, which is consistent with our prediction, a lack of association cannot prove the null hypothesis. Future research would benefit from exploring the relations between gender and state and indirect measures of clarity (e.g., Lischetzke, Cuccodoro, Gauger, Todeschini, & Eid, 2005), potentially using Bayesian analyses that are better suited to testing for the lack of relations between variables. Consistent with our hypotheses, women reported greater voluntary and involuntary attention than men. Future research is needed to directly investigate how stereotypes and socialization processes influence attention to emotions in men and women. For example, women might attend more to their emotions to navigate traditional, and thus, stereotyped gender roles. Indeed, from an early age women are expected to be more highly interpersonally cooperative and empathetic than men (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). These expectations might motivate women to attend to their emotions to successfully manage daily and longer-term tasks (e.g., Chaplin, Cole, & Zahn-Waxler, 2005).

Of the relations we examined between SES and emotional awareness facets, SES was only associated with type clarity. It will be important to examine the developmental contributions to type clarity. For example, SES is positively related to the development of a larger vocabulary in childhood through differences in parental communication (e.g., Hoff, 2003; Sohr-Preston, Scaramella, Martin, Neppl, Ontai, & Conger, 2013). If this general finding for vocabulary extends to emotional vocabulary—such that SES would be positively related to the development of a larger emotional vocabulary—then SES might contribute to type clarity and negative emotion differentiation. Because language can be considered a context within which the emotions of others can be perceived (e.g., Barrett, Lindquist, & Gendron, 2007), language could provide such a context for understanding one’s emotions. Although adult SES is positively associated with childhood SES (e.g., Pollitt, Kaufman, Rose, Diez-Roux, Zeng, & Heiss, 2007), a longitudinal study should test whether SES contributes to the development of type clarity and emotion differentiation. Future studies should examine SES and emotional awareness longitudinally in child samples.

The absence of relations between SES and the remaining facets could suggest a more complicated story. Some researchers posit that people with lower SES might be more strongly influenced by their external environments than people with higher SES (e.g., Kraus et al., 2010). The increased influence of the external environment might reduce the amount of attention allocated to their internal emotional experience, but also might facilitate less ambiguous identification of the potential sources of their emotions. In this case, lower SES would predict greater source clarity through a reduction in attention to emotion. Future prospective studies should test the interactions among emotional awareness facets and sociodemographic characteristics over time.

The current study has limitations that warrant discussion. First, just under two-thirds of participants provided a free response for occupation. Although the inclusion and exclusion of occupation resulted in similar patterns of findings, our SES results should be interpreted with caution. Second, a longitudinal design would clarify the directionality of the associations between sociodemographic characteristics and emotional awareness and would demonstrate how demographic characteristics contribute to developmental and socialization processes that influence emotional awareness. For example, research could examine whether as individual age, they develop greater type clarity, source clarity, and negative emotion differentiation to determine whether associations with age are development or cohort effects.

The current study identified a number of future directions that can further illuminate the sources, mechanisms, and downstream consequences of emotional awareness. Emotional awareness facets are differentially related to the use of specific emotion regulation strategies (Boden & Thompson, 2015). Extensive research demonstrates that gender is associated with differences in emotion regulation (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012; Tamres, Janicki, & Helgeson, 2002). Gender differences in the use of rumination (e.g., Johnson & Whisman, 2013) might be related to individual differences in emotional awareness. For example, rumination involves inflexible attention (involuntary attention) directed toward the causes (source clarity) and consequences of one’s negative emotions. Future research should examine how variation in age, gender, and SES reveals theoretically important differences in the relations among emotional awareness, emotion regulation, and psychopathology. Our results demonstrate the importance of considering age, gender, and SES in examinations of emotional awareness.

Highlights.

Older age was associated with greater emotional clarity and less involuntary attention

Women exhibited greater negative emotion differentiation than men

Women reported greater voluntary and involuntary attention to emotion than men

Higher socioeconomic status was associated with higher levels of type clarity

Social and developmental influences might contribute to emotional awareness

Acknowledgements

We thank Jordan Davis for managing the project and Haijing Wu for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. AMM was funded by National Institute of General Medical Sciences, T32GM081739.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The majority of participants (n > 900) reported income and education. A subset of the participants (n = 579) also reported all three indicators of SES (income, education, and occupation). Therefore, we used the mean of the SES indicators provided by each participant (i.e., some SES scores were computed with the mean of two indicators, while the majority were computed with the mean of all three indicators). To examine whether including only income and education in the computation of SES would result in a different pattern of results, we conducted an additional path analysis. This path analysis resulted in estimates of similar magnitude with only one exception (age and involuntary attention). Further, the patterns of significance between variables was replicated with the exception of SES on type clarity, which became marginally significant (p = .06).

Contributor Information

Annette M. Mankus, Department of Psychology, Washington University in St. Louis, 1 Brookings Dr., St. Louis, MO 63130

Matthew Tyler Boden, Center for Innovation to Implementation, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, 795 Willow Rd., Menlo Park, CA 94025.

Renee J. Thompson, Department of Psychology, Washington University in St. Louis, Department of Psychology, 1 Brookings Dr., St. Louis, MO 63130.

References

- American Psychological Association, Task Force on Socioeconomic Status . Report of the APA Task Force on Socioeconomic Status. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, Parker JDA. The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale—II. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1994;38:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90006-x. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF. Discrete emotions or dimensions? The role of valence focus and arousal focus. Cognition and Emotion. 1998;12:579–599. doi: 10.1080/026999398379574. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Gross J, Christensen TC, Benvenuto M. Knowing what you’re feeling and knowing what to do about it: Mapping the relation between emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cognition and Emotion. 2001;15:713–724. doi: 10.1080/02699930143000239. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Lindquist KA, Gendron M. Language as context for the perception of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007;11:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.003. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard-Fields F. Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult developmental perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:26–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00469.x. [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Berenbaum H. What you are feeling and why: Two distinct types of emotional clarity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51:652–656. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.009. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Berenbaum H. Facets of emotional clarity and suspiciousness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;53:426–430. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.010. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Gala S, Berenbaum H. Emotional awareness, sex, and peculiar body-related beliefs. Cognition and Emotion. 2013;27:942–951. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.752720. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.752720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Thompson RJ. Facets of emotional awareness and associations with emotion regulation and depression. Emotion. 2015;15:399–410. doi: 10.1037/emo0000057. doi: 10.1037/emo0000057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Thompson RJ, Dizén MD, Berenbaum H, Baker JP. Are emotional clarity and emotion differentiation related? Cognition and Emotion. 2013;27:961–978. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.751899. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.751899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody LR, Hall JA. Sex and emotion in context. In: Lewis M, Haviland-Jones JM, Feldman Barrett L, editors. Handbook of Emotions. 3rd The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 395–408. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL. The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science. 2006;312:1913–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.1127488. doi: 10.1126/science.1127488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Isaacowitz DM, Charles ST. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist. 1999;54:165–181. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165. doi: 10.1037/003-066X.54.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Pasupathi M, Mayr U, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:644–655. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.4.644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C. Parental socialization of emotion expression: Sex differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion. 2005;5:80–88. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Carstensen LL. Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:383–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbas Y, Ceulemans E, Pe ML, Koval P, Kuppens P. Negative emotion differentiation: Its personality and well-being correlates and a comparison of different assessment methods. Cognition and Emotion. 2014;28:1196–1213. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.875890. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.875890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin. 1971;76:378–382. doi: 10.1037/h0031619. [Google Scholar]

- Gasper K, Clore GL. Do you have to pay attention to your feelings to be influenced by them? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:698–711. doi: 10.1177/0146167200268005. [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL. Mood regulation and emotional intelligence: Individual differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:594–607. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohm CL, Clore GL. Individual differences in emotional experience: Mapping available scales to processes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:679–697. doi: 10.1177/0146167200268004. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton JL, von Hippel W. Stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology. 1996;47:237–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E. The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affect early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development. 2003;74:1368–1378. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead ADB. Four factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Huang SS, Berenbaum H, Chow PI. Distinguishing voluntary from involuntary attention to emotion. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;54:894–898. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.12.025. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DP, Whisman MA. Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysiss. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;55:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.019. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Barrett TB, McKnight PE. Unpacking emotion differentiation: Transforming unpleasant experience by perceiving distinctions in negativity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2015;24:10–16. doi: 10.1177/0963721414550708. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Farmer AS. Differentiating emotions across contexts: Comparing adults with and without social anxiety disorder using random, social interaction, and daily experiencing sampling. Emotion. 2014;14:629–638. doi: 10.1037/a0035796. doi: 10.1037/a0035796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Ferssizidis P, Collins RL, Muraven M. Emotion differentiation as resilience against excessive alcohol use: An ecological momentary assessment in underage social drinkers. Psychological Science. 2010;21:1341–1347. doi: 10.1177/0956797610379863. doi:10.1177/0956797610379863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus MW, Côté S, Keltner D. Social class, contextualism, and empathic accuracy. Psychological Science. 2010;21:1716–1723. doi: 10.1177/0956797610387613. doi: 10.1177/0956797610387613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International Affective Pictures System (IAPS): Technical manual and affective ratings (tech. Rep. A-4) University of Florida, Center for Research in Psychophysiology; Gainsville: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Libbrecht N, Lievens F, Carrette B, Côté S. Emotional intelligence predicts success in medical school. Emotion. 2014;14:64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0034392. doi: 10.1037/a0034392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lischetzke T, Cuccodoro G, Gauger A, Todeschini L, Eid M. Measuring affective clarity indirectly: Individual differences in response latencies of state. Emotion. 2005;5:431–445. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.4.431. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löckenhoff CE, Carstensen LL. Socioemotional selectivity theory, aging, and health: The increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1395–1424. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00301.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Seventh Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri PA, Boden MT, Berenbaum H. Measuring clarity of and attention to emotions. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2009;91:560–567. doi: 10.1080/00223890903228539. doi: 10.1080/00223890903228539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci G, Chandler J. Inside the turk: Understanding mechanical turk as a participant pool. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23:184–188. doi: 10.1177/0963721414531598. [Google Scholar]

- Perera HN, DiGiacomo M. The role of trait emotional intelligence in academic performance during the university transition: An integrative model of mediation via social support, coping, and adjustment. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;83:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.001. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt RA, Kaufman JS, Rose KM, Diez-Roux AV, Zeng D, Heiss G. Early-life and adult socioeconomic status and inflammatory risk markers in adulthood. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;22:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9082-1. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pond RS, Kashdan TB, DeWall CN, Savostyanova A, Lambert NM, Fincham FD. Emotion differentiation moderates aggressive tendencies in angry people: A daily diary analysis. Emotion. 2012;12:326–337. doi: 10.1037/a0025762. doi: 10.1037/a0025762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed AE, Chan L, Mikels JA. Meta-analysis of age-related positivity effect: Age differences in preferences for positive over negative information. Psychology and Aging. 2014;29:1–15. doi: 10.1037/a0035194. doi: 10.1037/a0035194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ready RE, Carvalho JO, Weinberger MI. Emotional complexity in younger, middle, and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2008;23:928–933. doi: 10.1037/a0014003. doi: 10.1037/a0014003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of boys and girls. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salovey P, Mayer JD, Goldman SL, Turvey C, Palfai TP. Emotional attention, clarity and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the trait meta-mood scale. In: Pennebaker JW, editor. Emotion, disclosure, & health. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe S, Carstensen LL. Emotional aging: Recent findings and future trends. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2010;65B:135–144. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp132. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohr-Preston SL, Scaramella LV, Martin MJ, Neppl TL, Ontai H, Conger R. Parental socioeconomic status, communication, and children’s vocabulary development: A third generation test of the family investment model. Child Development. 2013;84:1046–1062. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12023. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamres LK, Janicki D, Helgeson VS. Sex differences in coping behavior: A meta-analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6:2–30. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0601_1. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BL, Waltz J, Croyle K, Pepper AC. Trait meta-mood and affect as predictors of somatic symptoms and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:1786–1795. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.05.017. [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL, Barrett LF. Psychological resilience and emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1161–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vine V, Aldao A. Impaired emotional clarity and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic deficit with symptom-specific pathways through emotion regulation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2014;33:319–342. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2014.33.4.319. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau United States Census 2010. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/2010census/