Abstract

The giant protein titin spans half of the sarcomere length and anchors the myosin thick filament to the Z-line of skeletal and cardiac muscles. The passive elasticity of muscle at a physiological range of stretch arises primarily from the extension of the PEVK segment, which is a polyampholyte with dense and alternating-charged clusters. Force spectroscopy studies of a 51 kDa fragment of the human fetal titin PEVK domain (TP1) revealed that when charge interactions were reduced by raising the ionic strength from 35 to 560 mM, its mean persistence length increased from 0.30±0.04 nm to 0.60±0.07 nm. In contrast, when the secondary structure of TP1 was altered drastically by the presence of 40 and 80% (v/v) of trifluoroethanol, its force-extension behavior showed no significant shift in the mean persistence length of ~0.18±0.03 nm at the ionic strength of 15 mM. Additionally, the mean persistence length also increased from 0.29 to 0.41 nm with increasing calcium concentration from pCa 5–8 to pCa 3–4. We propose that PEVK is not a simple entropic spring as is commonly assumed, but a highly evolved, gel-like enthalpic spring with its elasticity dominated by the sequence-specific charge interactions. A single polyampholyte chain may be fine-tuned to generate a broad range of molecular elasticity by varying charge pairing schemes and chain configurations.

Introduction

Titin, also called connectin, is a family of giant elastic proteins (3–4 MDa) found mainly in skeletal and cardiac muscles (Wang et al., 1979; Maruyama et al., 1981) and its gene is notable for having 363 exons, the most in the whole human genome (Bang et al., 2001; Venter et al., 2001). Its multifaceted function includes the assembly of the muscle sarcomere, the maintenance of sarcomere symmetry and integrity and the generation of passive tension (e.g. see reviews (Wang, 1985; Horowits, 1999; Maruyama and Kimura, 2000; Wang et al., 2001; Tskhovrebova and Trinick, 2002; Tskhovrebova and Trinick, 2004). The long titin strands span half of the muscle sarcomere length, anchoring the myosin thick filament from the M-line to the Z-line. Titin has a segmented domain structure consisting mainly of tandem repeats of immunoglobulin-like (Ig) and fibronectin type III (Fn3) beta-barrels and a special PEVK segment of which more than 70% is composed of the four amino acids: P, E, V and K (Labeit et al., 1997; Freiburg et al., 2000). The extension of this unique segment accompanies the rise in passive tension when resting muscle is stretched moderately, while maintaining the overlap of the actin and myosin filaments (Linke et al., 1998; Horowits, 1999; Freiburg et al., 2000). However, the exact nature of both the structure and elasticity of the PEVK segment are still unresolved. It is often stated, on the assumption that the PEVK segment is a random coil or a permanently unfolded linear polypeptide (Labeit and Kolmerer, 1995; Labeit et al., 1997; Linke et al., 1998), that PEVK resists stretching by maximizing entropy and behaving as a worm-like chain (WLC) (Bustamante et al., 1994; Wang et al., 1997; Greaser, 2001). However, recent evidence of tandem repeats of 28-mer PEVK modules (Freiburg et al., 2000; Greaser, 2001; Gutierrez-Cruz et al., 2001) and the existence of left-handed polyproline II helices in the PEVK modules) raises questions about the assumed ‘randomness’ of the PEVK polypeptides. Modeling of PEVK elasticity based on the passive tension of myofibrils also indicates a significant enthalpic contribution (Linke, et al., 1998).

Previous investigations of the elastic property of titin by single-molecule techniques focused mainly on the sequential unfolding of the numerous Ig and Fn3 domains in titin [reviewed by (Wang et al., 2001)]. Those studies of intact titin and the Ig/Fn3 domains have provided a deeper understanding of how the elasticity of titin is adjusted by the sequential unfolding of Ig/Fn3 domains and how its elasticity recovers after domain refolding (Kellermayer et al., 1997; Rief et al., 1997; Carrion-Vazquez et al., 2000). More recently, the mechanical properties of expressed PEVK fragments based on cardiac and soleus PEVK exons were reported (Li et al., 2001, 2002; Linke et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 2002; Labeit et al., 2003; Sarkar et al., 2005). Each study observed an unexpectedly broad distribution in the measured elastic persistence length of the PEVK segment. However, these investigators have attributed the breadth of the distribution to different mechanisms. Li et al. speculated that the range of persistence lengths that they detected (0.5–2.5 nm) resulted from different amounts of cis and trans proline resides and polyproline types I and II helices in the peptide chain. Watanabe et al. observed both multiple peaks and a large breadth (0.1–2.5 nm) in their histogram of persistence lengths and attributed these findings to the stretching of one, two or three molecules simultaneously. Linke et al. attributed the breadth of persistence lengths in AFM measurements of purified proteins and in mechanical measurements of cardiac myofibrils to the PEVK segment taking on multiple conformations. Labeit et al. found that the distribution of persistence lengths from their engineered PEVK constructs based on soleus exons was multimodal. The presence of non-PEVK globular domains in the protein constructs used in all of these investigations (except for one construct used by Labeit et al. (2003)) unfortunately did not allow for conformational insights of the PEVK domains by circular dichroism, since such spectra would be dominated by the high molar ellipticity of α-helix and β-sheet structures in the globular domains. No CD spectra of the recombinant PEVK without the flanking Ig domains were reported by (Labeit et al., 2003). Since there are currently no structural data on the cardiac PEVK exons, the structural interpretation of PEVK elasticity is necessarily speculative and most investigators assume that cardiac PEVK is an entropic spring that behaves as WLCs.

The mechanical properties of the PEVK segment of skeletal muscle titin have also been inferred indirectly from the elasticity of whole titin molecules or sarcomere (Tskhovrebova et al., 1997; Kellermayer et al., 1998, 1997, 2001; Linke et al., 1998). Again, the absence of conformational data for skeletal PEVK exons made such interpretation tentative.

Experimentally, we approached this question by examining the ionic strength dependence of the local elasticity of an expressed PEVK fragments, based on human fetal exons. The direct mechanical measurements at the single-molecule level with an atomic force microscope indicate consistently broad distributions of the PEVK elastic parameters. Our correlative mechanical and conformational analysis, however, indicates that electrostatic interactions between segments of the polypeptide play a major role in PEVK elasticity and may very well account for the highly heterogeneous elasticity. Unexpectedly, the PEVK persistence length distribution varied with ionic strength, which does not alter the conformation, but not with the concentration of trifluoroethanol (TFE), which does alter the secondary structure. Additionally, the persistence length distribution shifts abruptly when going from low calcium concentration (pCa 5–8) to high calcium concentration (pCa 3–4), but the conformation does not change. Further sequence analysis of the charge patterns of PEVK exons led us to propose that PEVK is not a simple entropic spring as is commonly assumed, but a highly evolved gel-like enthalpic spring with its elasticity dominated by sequence-specific charge interactions and fine tuned by its variable charge pairing schemes and wrapping or chain configurations of these ‘nano-gels.’ A preliminary presentation of this work was published in a meeting abstract (Jin, A.J., Forbes, J.G., and Wang, K. 2000. Biophys. J. 78: 381A–381A).

Results and discussion

Titin PEVK is a polyampholyte with dense, periodic and alternating charges

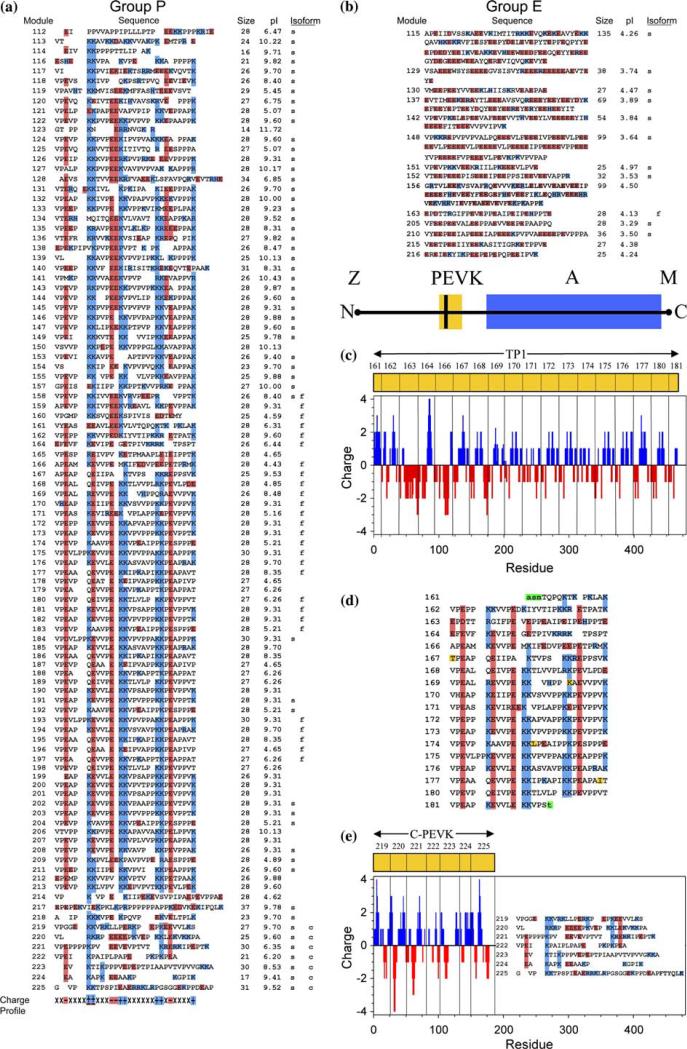

The PEVK segments of various titin isoforms of human muscle vary in length from 186 amino acid residues in human heart to ~2200 residues in human soleus muscle (Freiburg et al., 2000). These ‘iso-segments’ arise from tissue- and development-specific assembly (Bang et al., 2001; Gutierrez-Cruz et al., 2001) of selected protein modules encoded by 113 of the 363 human titin exons (GenBank AJ277892, latest update 11/2001). These exons encode two classes of protein sequence repeats classified as PPAK (Group P) and PolyE (Group E) (Greaser, 2001; Gutierrez-Cruz et al., 2001). Group P contains close to 100 exons encoding homologous PEVK modules that are enriched in amino residues P, E, V, and K, with an average of 28 residues. The second class encodes variable length modules enriched in E's. The majority of acidic and basic residues are clustered with two or more in tandem. One of the most striking features of Group P modules is the high sequence homology, especially the distribution of charged residues or cluster of residues along the length of each module (Figure 1a). The charge profile of most Group P modules can be represented as

This is illustrated by highlighting both acidic residues (mainly E's, red) and basic residues (K and R, blue) in the aligned sequences, allowing up to three gaps in alignment (Figure 1a). Thus, there are seven charge clusters, each with up to three residues. The first cluster is primarily an E. The second cluster varied widely from EE, E, EK, EKK, K, KK to KKK. The third one is mainly E or EE, the fourth and fifth ones are mainly K or KK, the sixth is E, EE or EEE, and the seventh is mainly K. Within Group P, there are ~20 modules that deviate significantly from this charge profile consensus, yet still retain some of the characteristic charge clusters. The major variation from this pattern is located at the beginning (modules 112–119) and the end (modules 214–225) of the PEVK modules, as well as a few in the middle (modules 160 and 166). Most of the Group P modules are basic with pI around 9–10 (70 exons with pI>7, 30 exons with pI<7). Group E modules are rich in tandem repeats of glutamate, E, EE, EEE, EEEE and EEEEE, with pI in the range of 3.29–4.97. Some repeating motifs, such as VLPEEEE in module 148 are present. These Group E modules are found mostly in soleus and fetal PEVK, but absent in cardiac PEVK. All seven Group P modules coding for cardiac PEVK display significant variation from the modules coding for fetal titin, still with alternating charge clusters, but not the periodicity of TP1.

Fig. 1.

Charge profiles of human PEVK exon modules. PEVK module sequences were deduced from exon DNA sequences (AJ277892, 11/ 23/2001) by including the final G in the preceding exon as the first base. A total of 113 PEVK exons were classified into two groups: (a) 100 PEVK exons designated as Group P, (b) 13 PEVK modules designated as Group E. (a, b) The tables include the module (exon) number and its corresponding sequence. The corresponding module size (number of amino acids), pI and the module composition of human soleus (designated as s’), fetal (designated as f’) and cardiac (designated as c’) PEVK of titin isoforms are listed to the right of the table. All acidic amino acids (e and d) and basic amino acids (K, R, H) were marked with red and blue backgrounds, respectively. The charge profile for most of modules in Group P is shown on the bottom of the table (a), with +, −, × indicating basic (blue), acidic (red) and other amino acids, respectively. (c) The sarcomere location of the PEVK segment in titin that spans from the Z-line to the M-line. The sequence of 18 PEVK modules that make up the TP1 fragment of the human fetal skeletal titin PEVK segment (AF321609) are shown (d), with the exon numbering scheme used by Bang et al. (2001) and the acidic and basic residues highlighted in red and blue respectively. The charge profile along TP1 at pH 7.0 with a 5-residue window showing an exceptionally high density of alternating charges in TP1 were calculated using the ISOELECTRIC program from the GCG Wisconsin Package. Our TP1 sequence differs from that reported by Bang et al. (2001) as follows: T, K, L and I, instead of A, QR, V, V in exons 167, 169, 174 and 177 (marked in yellow). The residues in lower case italic (in green) were extras added during cloning. Further details of TP1 may be found elsewhere (Gutierrez-Cruz et al., 2001). (e) Charges along cardiac PEVK sequence calculated as for TP1. Cardiac PEVK is assembled from seven different modules and its sequence is shown in the inset (Bang et al., 2001).

It is worth noting that, with the exception of the first E, all basic and acidic clusters occupy the coil regions of the three ‘PhC’ (PPII helix-Coil) conformational motifs as identified previously in module 172 (Ma et al., 2001). The first E is part of the short PPII helix and the remaining two PPII's are bracketed by charged residues. The SH3 binding PPII in module 172 is bracketed by the KK clusters of the fifth and sixth positions (Ma and Wang, 2002). The local charge density along the module is therefore much higher than that suggested by its amino acid composition. Furthermore, the charge profile along TP1 at pH 7.0, estimated with a 5-residue window moving average, showed an exceptionally high density of alternating charges in TP1.

Titin isoforms and human fetal TP1

PEVK exons are assembled via differential splicing in a tissue and development-specific manner, to generate variable length and charge profiles of the PEVK segment in titin isoforms in the different muscle types (Bang et al., 2001; Gutierrez-Cruz et al., 2001). The sequence and charge profile of the entire PEVK segment thus reflects the linkage and the profiles of each individual module. The modules expressed in human soleus (GenBank, CAD12456), fetal (GenBank, AF321609) and cardiac PEVK (GenBank, AJ277892) are tabulated in Figure 1c and d. Interestingly, modules expressed in the partial human fetal PEVK are nearly completely absent in adult human soleus and cardiac PEVKs, whereas all cardiac modules are also found in soleus PEVK. The charge profiles of the cloned, human fetal titin fragment, TP1, (Figure 1d) and cardiac PEVK were analyzed further by plotting charges, weighted as a five-residue peptide at pH 7, along the length (Figure 1c and e). The well-behaved, soluble TP1 is comprised of 17 full or partial Group P modules and one Group E module. Such a charge profile mimics the intrinsic (i.e. no counter ions) relative charge distribution along the contour of TP1 in a fully extended form at pH 7. While both TP1 and cardiac PEVK have alternating clusters of like charges, the charge clusters in TP1 are clearly more periodic by visual inspection.

The PEVK segments are thus densely charged polypeptides of variable length, with sequence and charge profile reflecting the linkage and the profiles of each individual module. Since these proline-rich modules do not appear to take on α-helical or β-sheet conformations (Adzhubei and Sternberg, 1993; Williamson, 1994), it is unlikely that they fold into globular domains, therefore PEVK segments are open, flexible polyampholytes.

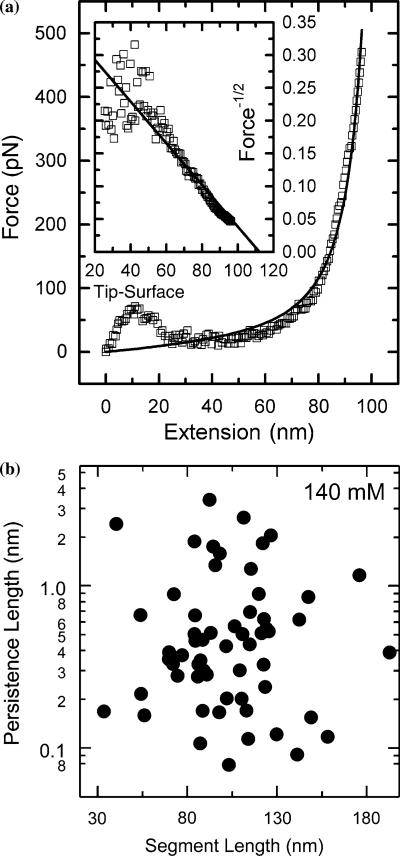

TP1 force-extension modeled as a WLC

Elastic force-extension measurements were conducted over TP1 protein populations on gold substrates with sub-monolayer coverage. A typical AFM force trace is shown in Figure 2a. To maximize the chances of capturing a single TP1 protein between the substrate surface and the AFM tip, a field with sub-confluent protein coverage was selected. The AFM tip was then pressed into the protein-decorated surface repeatedly at controlled rates of about 500 nm/s. Force spectra showing recognizable elastic curves were observed in approximately one out of every 10 attempts and recorded using the instrument control software. Occasionally, force spectra having two or more discrete elastic curves were observed and may represent multiple polypeptide chain stretches. Occasionally, large tip–surface adhesion forces were also seen to dominate the force spectra. These two types of force spectra represented less than 20% of our recorded curves. The elastic curve farthest away from the tip/surface contact and well separated from any other features represents single TP1 molecule stretching. Only those curves with analyzable elastic segments were included in our analysis and all others were excluded. Several hundreds of force curves were typically acquired under each solution condition to address the variability inherent in single-molecule measurements and to allow for adequate statistical evaluation and treatment. Since a distribution of the elastic behavior was expected, several hundred curves were recorded to sample a wide range of TP1 molecules. Force-extension curves (Figure 2a) revealed that the force response of TP1 was non-linear and approximately exponential as in the WLC model before the detachment of the polymer (see Wang et al. (2001) for details of polymer elasticity models). Each force curve resulted from the extension and detachment of single segment of the PEVK polypeptide under low protein coverage. Multiple extension-rupture curves were observed and excluded from analysis. Excluding the tip–surface interactions at small separation (≤20 nm), the PEVK elasticity curves at larger extension were well fitted by the WLC model. The resulting parameters showed a random distribution that had no detectable correlation between L and P (Figure 2b). For the majority of the curves, the persistence length ranged between 0.2 and 1 nm, centered on 0.45 nm (Figure 2b). The stretching of TP1 occurred over variable contour lengths from about 30 to 150 nm. The detachment force of the maximally extended attached portion of TP1 was typically 100– 500 pN. The average segment length of 100 nm was about 2/3 of the maximally extended polypeptide length of TP1 at 180 nm (473 residues×0.38 nm/residue). Histograms of persistence lengths show only a single peak when plotted on both linear and log scales (data not shown), indicating that it is unlikely we are stretching multiple chains to any appreciable degree. Distributions of both the persistence length and the pull-off force exhibited normal distributions when plotted on log scales (Crow and Shimizu, 1988). The broad distributions of the fitted persistence lengths (Figure 2b and Table 1) and the measured pull-off force are addressed in more detail below.

Fig. 2.

WLC modeling of TP1 elasticity and distribution of elastic parameters. (a) A representative force-extension curve showing the curve fitting with WLC parameters of persistence length P=0.14 nm, detachment force Df=470 pN, and segment length L=110 nm. See (Wang et al., 2001) for details of different models of polymer elasticity. The zero point for data fitting is assumed to be the Z position of the retraction curve where the force is equivalent to that at the non-interacting equilibrium position. The inset is a plot of F−½ vs. z, which linearizes the WLC force response at large extensions. (b) Scatter plot of persistence length as a function of segment length of 61 force-distance curves (TP1, ionic strength=140 mM, pH=7.0, pCa=7.0 at 23°C). See (Forbes et al., 2001) for details of experimental setup.

Table 1.

Statistics of force curves of TP1 molecules

| Ionic strength | Average persistence length (nm, lognormal distribution) |

Detachment force (pN) (Lognormal distribution) |

Segment length (nm) (normal distribution) |

Samples (counts) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFE% | Mean | SE+/− | Mean | SD+/− | Mean | SD | ||

| 560 | 0 | 0.60 | 0.08/0.07 | 170 | 143/78 | 96 | 35 | 79 |

| 280 | 0 | 0.44 | 0.05/0.05 | 171 | 139/77 | 111 | 30 | 66 |

| 140 | 0 | 0.42 | 0.06/0.05 | 197 | 172/92 | 108 | 33 | 64 |

| 70 | 0 | 0.34 | 0.05/0.04 | 220 | 202/105 | 93 | 27 | 72 |

| 35 | 0 | 0.29 | 0.04/0.03 | 212 | 235/112 | 127 | 41 | 68 |

| 15 | 0 | 0.176 | 0.012/0.011 | 253 | 119/81 | 59 | 14 | 54 |

| 15 | 40 | 0.201 | 0.014/0.014 | 326 | 156/106 | 62 | 25 | 71 |

| 15 | 80 | 0.141 | 0.010/0.009 | 403 | 277/164 | 91 | 29 | 53 |

| pCa | ||||||||

| 3 | 0.3924 | 0.036/0.039 | ND | ND | 89 | 34 | 103 | |

| 4 | 0.4381 | 0.043/0.047 | ND | ND | 137 | 49 | 135 | |

| 5 | 0.263 | 0.025/0.027 | ND | ND | 112.9 | 41 | 129 | |

| 6 | 0.3225 | 0.026/0.028 | ND | ND | 107.2 | 35 | 91 | |

| 8 | 0.2979 | 0.025/0.028 | ND | ND | 128.4 | 60 | 96 | |

The persistence length and detachment force in Figures 2 and 3 are in agreement with lognormal distributions and the segmental length is in agreement with normal distribution. For lognormal distribution, standard statistic procedures give (a) the average, Mean = 10, (b) the upper and lower standard deviation limit, SD+/−=10 (10σ[log(X)]–1)/10 (1–10–σ[ log(X)]), and (c) the upper and lower standard error limit, SE+/−=10 〉log(X)〈 (10SE(log(X)]–1)/10 〉log(X)〈 (1–10–SE[log(X)]). For a normal distribution, standard error SE represent the uncertainty range of the mean value and is related to the standard deviation SD of the sample distribution as, SE=SD/ √(N[shy]1) where N is the sample counts. I=ionic strength.

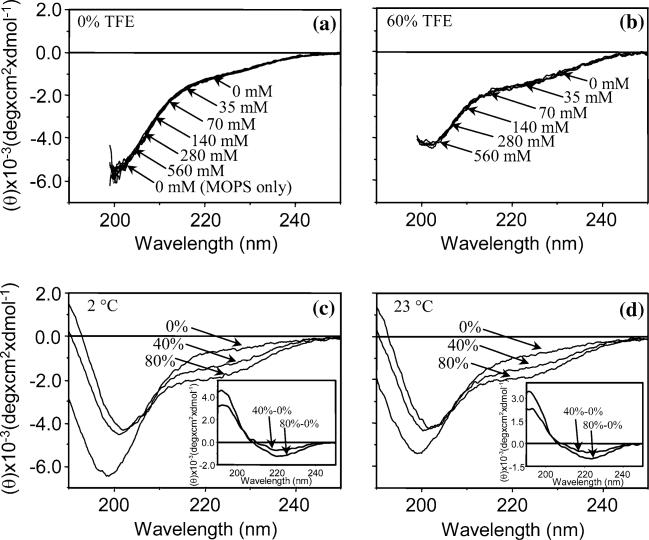

Ionic strength significantly affects TP1 elasticity, but not its secondary structure

To determine whether charge–charge interactions between the abundant ionic residues of TP1 would affect its elasticity, force curves of TP1 at various ionic strengths were measured over the same sample population by fluid-cell solution exchanges. The ionic strength dependence of TP1 elasticity was clearly evident from these measurements (Figure 3a). The mean persistence length of TP1 increased from an average of 0.30±0.04 nm to 0.60±0.07 nm when the ionic strength was increased from 35 to 560 mM (Figure 3a). The average segment length was comparable throughout the whole ionic strength range at ~100 nm (Figure 3b). The average detachment force at maximum TP1 extension remained relatively constant at about 220 to 170 pN (Figure 3b). The plotted persistence length and detachment force were from log-normal average values and their standard errors and standard deviations, respectively. The segment lengths varied linearly and were plotted as normal distribution means and their respective standard deviation ranges (Figure 3b and d). These statistics were chosen on the basis of the underlying stochastic distribution obtained for these parameters. As the solution ionic strength increased from 35 to 560 mM, the charge screening effect increased, as measured by the decrease of the Debye–Hückel length (that is proportional to (ionic strength)−½) from 1.6 to 0.4 nm (Figure 3a) (Baumann et al., 1997; Podgornik et al., 2000). At an ionic strength of 15 mM, the Debye–Hückel length increases to about 2.5 nm, so the exponential screening of charge interactions is much weaker. The correlation of the steep increase of PEVK persistence length and the sharp drop of Debye–Hückel length in the range of 35–140 mM ionic strength (Figure 3a) is especially striking and strongly suggests that charge–charge interactions play a dominant role in the apparent WLC persistence length of PEVK (Odijk, 1995; Baumann et al., 1997; Ha and Thirumalai, 1997; Ma et al., 2001; Podgornik et al., 2000).

Fig. 3.

Effects of ionic strength and TFE on TP1 elasticity. (a) The mean persistence lengths (closed circles with standard error bars, ●) and the Debye–Hückel screening length (inverted triangles, ▽) as a function of ionic strength from 35 to 560 mM. (b) The segment lengths (closed triangles, ▲) and detachment forces (open circles, ○) as a function of ionic strength. Error bars denote one standard deviation computed from the distributions. Experiments were carried out at room temperature (23°C) in buffer B (10 mM imidazole, 10 mM K-EGTA, 2.1 mM CaCl2, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaN3, pH 7.0, pCa 7.0), with the ionic strength adjusted with KCl. Free [Mg2+]=2.0 mM. pCa=7.0±0.1. (c) The mean persistence lengths (closed circles with standard error bars, ●) as a function of TFE concentration. (d) The segment lengths and detachment forces as a function of TFE concentration. Error bars denote one standard deviation computed from the distributions. Data were taken at 2°C in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH=7 and ionic strength at 15 mM). Data collection and analysis as in Figure 2.

To determine whether the ionic strength alters TP1 peptide conformation, circular dichroism spectra (CD) were obtained under a similar range of ionic conditions (Figure 4a and b). Changing the ionic strength had no effect on the CD spectra of TP1 protein (Figure 4a). This indicates that the average peptide conformation of the PEVK protein was not affected by the ionic interactions. Furthermore, no detectable spectral changes were observed in the absence or presence of MOPS-EGTA buffer, suggesting that these chemicals have no effect on the conformation of TP1. Changing the ionic strength of TP1 in 60% TFE/buffer (10 mM KPi, pH 7.0) similarly caused no further spectral change than those caused by 60% TFE alone (Figure 4b).

Fig. 4.

CD spectra for TP1 at different ionic strengths, temperatures and TFE concentrations. (a) CD spectra at ionic strengths of 0, 35, 70, 140, 280, and 560 mM KCl in 10 mM MOPS, pH7.0 with 10 mM K-EGTA, 2.1 mM CaCl2, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaN3, at 23°C. (b) CD spectra at ionic strengths of 0 mM, 35, 70, 140, 280 mM, and 560 mM KCl in 60% TFE in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, at 23°C. (c, d) CD spectra at 2 and 23°C at 0, 40 and 80% TFE in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0. Inset: difference CD spectra. Concentration of TP1 was 5 μM for all experiments. Spectra were recorded with a 1.0 nm bandwidth and resolution of 0.1 nm over the wavelength range 190 to 250 nm in a 0.1 cm path length cell. See (Ma and Wang, 2002) for further experimental details.

TTE affects TP1 secondary structure, not its elasticity

We have observed a marked effect of TFE on the secondary structure of TP1 as measured by CD spectroscopy. The CD spectra for TP1 in increasing amounts of TFE at two temperatures (2 and 23 C) indicated major changes in secondary structure (Figure 4c and d). The negative band at 199 nm in aqueous solution was lifted upward and red-shifted to 203 nm in 40% TFE and further to 204 nm in 80% TFE. The shoulder at 224 nm decreased with increasing TFE. These changes are consistent with the formation of α-helix and/or β-turn in TFE solution. The CD difference spectra (Figure 4c and d, insets) revealed the presence of type I β-turn rather than α-helix, which has a positive peak at 192 nm and negative bands around 224 nm (Woody, 1996).

Unexpectedly, and in contrast to the strong dependence on ionic strength, the mean persistence length did not vary significantly with the TFE concentration. The stochastic distribution of the persistence length at each TFE concentration was similar to that for various higher ionic strengths as tabulated in Table 1. Also the average persistence length was 0.19±0.04 nm for 0 and 40% TFE and appeared slightly smaller at 0.14±0.01 for 80% TFE (Figure 3c). These average persistence length values are consistent with an extrapolation of the ionic strength data in Figure 5a to 15 mM. The statistical mean segment lengths were ~70 nm and the mean detachment forces increased from 250 to 400 pN for the higher TFE concentration (Figure 3d). In all cases, comparable distributions of the elastic parameters were obtained for the TFE data and the ionic strength data (Table 1). These results demonstrate a limited effect of TFE on PEVK/TP1 elasticity at the force sensitivity and extension rates explored in our AFM measurements.

Fig. 5.

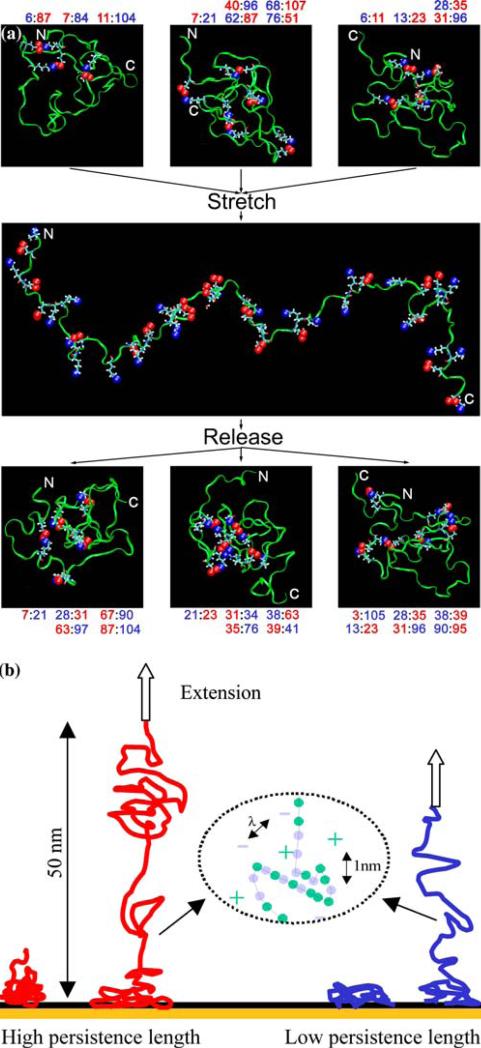

Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrating the manifold of configurations that PEVK can adopt after synthesis and stretching. (a) Probable structures for the fetal PEVK exons 170–173 (Gutierrez-Cruz et al., 2001) were generated using the TRADES software package (Feldman and Hogue, 2000). Plausible conformers were generated with FOLDTRAJ. Six with the smallest radius of gyration and one with the largest were selected and put into a water box such that at least 5Å of water surrounded the protein, with five Cl− ions to neutralize the system. The systems were minimized for 1000 steps and subjected to 1000 ps of molecular dynamics simulation using NAMD (Kale et al., 1999) with a molecular interaction cutoff of 10Å. The simulations were setup and visualized with VMD (Humphrey et al., 1996). Selected lysine and glutamate residues are highlighted showing how neighboring chains interact through the charge pairs. The oxygen atoms on the glutamate residues are shown in red and the nitrogen atom on the lysine residues in blue. Color coded numbers indicate the residues forming salt bridges. The structures at the top are three of many possible configurations that the polypeptide can adopt. When the polypeptide is stretched, the chain becomes extended and the charge groups can no longer interact. The middle panel shows a highly extended (although not fully) configuration with all of the charge groups highlighted. Upon release, compact configurations reform with different charge pairing schemes as shown in the bottom panel. In each structure the N’ indicates the amino terminus of the polypeptide chain. This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf PC/Linux cluster at the NIH, Bethesda, MD (http://biowulf.nih.gov). (b) One polyampholyte-many springs. Two different wrapping’ schemes of charge interactions may lead to distinct persistence lengths. The mechanical stretching extends polypeptides over length scales of tens to hundreds of nanometers, and affects charge interactions at the nanometer scale that is comparable to the charge screening length, λ.

Calcium concentration affects TP1 elasticity, but not its secondary structure

To determine whether charge–charge interactions between the abundant glutamate residues of TP1 and Ca+2 would affect its elasticity, force curves of TP1 at various pCa values were measured over the same sample population by fluid-cell solution exchanges. The mean persistence length increased from 0.29 to 0.41 nm with increasing calcium concentration from pCa 5–8 to pCa 3–4, Table 1. The persistence length did not increase monotonically with calcium concentration over the range study, but changed abruptly between pCa 4 and pCa 5. The average segment length was comparable throughout the whole pCa range at ~115 nm (Table 1).

To determine whether calcium concentration alters TP1 peptide conformation, circular CD were obtained under a similar range of pCa (data not shown). Changing the pCa in a NH4COOH-EGTA buffer had no effect on the CD spectra of TP1 protein and yielded spectra similar to those in varying ionic strength (Figure 4a) This indicates that the average peptide conformation of the PEVK protein was not affected by the change in calcium ion concentration. The 41% increase in persistence length of TP1 when going from a pCa of 5–8 to a pCa of 3–4 (Table 1) is similar in direction and magnitude to the change in persistence length when going from an ionic strength of 35 to 140 mM (Table 1). Calcium dependent changes in the elasticity of fragment of soleus PEVK have been reported recently (Labeit et al., 2003). However, in soleus PEVK the persistence length decreases monotonically from pCa 9 to pCa 3 by about 11%. In TP1, chelation of calcium by the glutamates would reduce the number of possible salt bridges that could form, leading to an increased persistence length.

Mechanisms for broad dispersion of PEVK elasticity

Our force spectroscopy experiments show a broad dispersion of molecular elasticity. Several mechanisms are conceivable and supported by molecular dynamics simulations (Figure 5). The first one is that each polypeptide chain can wrap into different configurations, with different networks of electrostatic interactions (Figure 5a). Each of these configurations will have a different force response (Figure 5b). When PEVK is stretched and then released, different energetically or kinetically equivalent charge interactions may lead to a new set of configurations. Charge screening will affect the propensity of the peptide chains to self-interact and will alter the distribution of configurations and therefore persistence lengths. Linke et al. (1998) and Minajeva et al. (2001) previously observed that titin-based dynamic stiffness decreased with higher ionic strength in myofibrils that have been treated with gelsolin to selectively remove the actin and tropomyosin/ troponin. Since a major change in the ionic environment of titin PEVK is expected following the removal of acidic actin protein, the observed ionic strength-sensitivity of titin stiffness may well reflect alteration of charge pairing schemes of PEVK in the proximity of parallel PEVK segments or highly basic nebulin that resisted extraction (Funatsu et al., 1994; Gutierrez-Cruz et al., 2001). The direct interaction of titin PEVK with nebulin and actin in a calcium and S100A sensitive manner in the skeletal sarcomere represent a separate and distinct mechanism of modulating titin molecular elasticity (Trombitas and Granzier 1997; Gutierrez-Cruz et al., 2001; Linke et al., 2002).

In summary, we propose that distributed configurations resulting from the high density of charged amino-acid residues in this extremely flexible PEVK protein are a major contributor to the broad distribution of persistence length.

Conclusion

Ex una plurimae spirae: out of one (polyampholyte) – many springs

While most biopolymers are polyampholytes, the open configuration, flexibility and charge profiles of the titin PEVK segment distinguish itself structurally and mechanically from the globular domains of titin (with their signature sawtooth force curves) (Rief et al., 1997) as well as to stiff DNA molecules (Baumann et al., 1997; Podgornik et al., 2000), and rigid polyampholytes (Ha and Thirumalai, 1997) for which the persistence length decreases with increasing ionic strength. It is worth noting that different wrapping schemes allowed by a flexible and highly charged polymer may well be the basis for a novel mechanism that creates a broad range of elasticity from a single poly-peptide or possibly parallel polypeptides in the sarcomere. This ‘one polyampholyte-many springs’ concept has intriguing implications. If a given unique polypeptide sequence can be wrapped into many configurations, each with a different intrinsic elasticity, then during sarcomere stretching, the ensemble of PEVK configurations unravel in the order of persistence length and thus provide a highly desirable smoothing of the stochastic nature of the individual molecules. In contrast, the abrupt mechanical unfolding of globular domains such as Ig and Fn would lead to a bumpy response all with the approximately the same force for a given extension rate. If the elasticity only occurred in such a step-wise manner, different parts of the sarcomere could potentially extend significantly different from others. The broad range of elastic responses provided by PEVK would ensure a homogeneous stretching of individual sarcomeres (Wang et al., 2001). In the sarcomere, direct screening of the charge–charge interactions in the PEVK segment may result from binding with exogenous ions such as calcium (Labeit et al., 2003) or with charge-rich thin filament proteins such as nebulin, actin, tropomyosin and troponin, or calcium sensor proteins such as S100 and calmodulin (Gutierrez-Cruz et al., 2001; Yamasaki et al., 2001; Linke et al., 2002; Ma and Wang, 2002). Moreover, the different peptides coded for by the PEVK exons may exhibit different behaviors when subject to these different perturbations, even though they may have similar sequences. This would lead to an exquisitely sensitive way of modulating titin elasticity for any given PEVK isoform, depending on its environment and interactions with other proteins and ions, and the degree and history of stretching and external mechanical load.

In view of the myriad of titin PEVK-like exons in vertebrate and invertebrate muscles and the developmentally and tissue-regulated differential splicing of these PEVK exons to generate chemical diversity of this important spring element (this volume), the proposed physical and mechanical diversity of each PEVK polyampholyte presents new challenges in more ways than one.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAMS, NIH, HHS.

References

- Adzhubei AA, Sternberg MJE. Left-handed polyproline-ii helices commonly occur in globular-proteins. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:472–493. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang ML, Centner T, Fornoff F, Geach AJ, Gotthardt M, McNabb M, Witt CC, Labeit D, Gregorio CC, Granzier H, et al. The complete gene sequence of titin, expression of an unusual approximate to 700-kDa titin isoform, and its interaction with obscurin identify a novel Z-line to I-band linking system. Circ Res. 2001;89:1065–1072. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann CG, Smith SB, Bloomfield VA, Bustamante C. Ionic effects on the elasticity of single DNA molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6185–6190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante C, Marko JF, Siggia ED, Smith S. Entropic elasticity of lambda-phage DNA. Science. 1994;265:1599–1600. doi: 10.1126/science.8079175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion-Vazquez M, Oberhauser AF, Fisher TE, Marszalek PE, Li H, Fernandez JM. Mechanical design of proteins studied by single-molecule force spectroscopy and protein engineering. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2000;74:63–91. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(00)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow EL, Shimizu K. Lognormal Distributions: Theory and Application. Dekker; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman HJ, Hogue CWV. A fast method to sample real protein conformational space. Proteins. 2000;39:112–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes JG, Jin AJ, Wang K. Atomic force microscope study of the effect of the immobilization substrate on the structure and force-extension curves of a multimeric protein. Langmuir. 2001;17:3067–3075. [Google Scholar]

- Freiburg A, Trombitas K, Hell W, Cazorla O, Fougerousse F, Centner T, Kolmerer B, Witt C, Beckmann JS, Gregorio CC. Series of exon-skipping events in the elastic spring region of titin as the structural basis for myofibrillar elastic diversity. Circ Res. 2000;86:1114–1121. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.11.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funatsu T, Anazawa T, Ishiwata SI. Structural and functional reconstitution of thin-filaments in skeletal-muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1994;15:158–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00130426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaser M. Identification of new repeating motifs in titin. Proteins. 2001;43:145–149. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20010501)43:2<145::aid-prot1026>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Cruz G, Van Heerden AH, Wang K. Modular motif, structural folds and affinity profiles of the PEVK segment of human fetal skeletal muscle titin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7442–7449. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha BY, Thirumalai D. Persistence length of intrinsically stiff polyampholyte chains. J Phys II. 1997;7:887–902. [Google Scholar]

- Horowits R. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharm. Springer-Verlag Berlin; Berlin: 1999. The Physiological Role of Titin in Striated Muscle. pp. 57–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:33. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale L, Skeel R, Bhandarkar M, Brunner R, Gursoy A, Krawetz N, Phillips J, Shinozaki A, Varadarajan K, Schulten K. NAMD2: greater scalability for parallel molecular dynamics. J Comput Phys. 1999;151:283–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kellermayer MSZ, Smith SB, Bustamante C, Granzier HL. Complete unfolding of the titin molecule under external force. J Struct Biol. 1998;122:197–205. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1998.3988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermayer MSZ, Smith SB, Bustamante C, Granzier HL. Mechanical fatigue in repetitively stretched single molecules of titin. Biophys J. 2001;80:852–863. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76064-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellermayer MSZ, Smith SB, Granzier HL, Bustamante C. Folding-unfolding transitions in single titin molecules characterized with laser tweezers. Science. 1997;276:1112–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeit D, Watanabe K, Witt C, Fujita H, Wu YM, Lahmers S, Funck T, Labeit S, Granzier H. Calcium-dependent molecular spring elements in the giant protein titin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13716–13721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235652100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeit S, Kolmerer B. Titins – giant proteins in charge of muscle ultrastructure and elasticity. Science. 1995;270:293–296. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labeit S, Kolmerer B, Linke WA. The giant protein titin – Emerging roles in physiology and pathophysiology. Circ Res. 1997;80:290–294. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HB, Linke WA, Oberhauser AF, Carrion-Vazquez M, Kerkviliet JG, Lu H, Marszalek PE, Fernandez JM. Reverse engineering of the giant muscle protein titin. Nature. 2002;418:998–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature00938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HB, Oberhauser AF, Redick SD, Carrion-Vazquez M, Erickson HP, Fernandez JM. Multiple conformations of PEVK proteins detected by single-molecule techniques. Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10682–10686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191189098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke WA, Ivemeyer M, Mundel P, Stockmeier MR, Kolmerer B. Nature of PEVK-titin elasticity in skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8052–8057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke WA, Kulke M, Li HB, Fujita-Becker S, Neagoe C, Manstein DJ, Gautel M, Fernandez JM. PEVK domain of titin: an entropic spring with actin-binding properties. J Struct Biol. 2002;137:194–205. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2002.4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Kan LS, Wang K. Polyproline II helix is a key structural motif of the elastic PEVK segment of titin. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3427–3438. doi: 10.1021/bi0022792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K, Wang K. Interaction of nebulin SH3 domain with titin PEVK and myopalladin: implications for the signaling and assembly role of titin and nebulin. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama K, Kimura S. Connectin: from Regular to Giant Sizes of Sarcomeres. Elastic Filaments of the Cell. 2000:25–33. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4267-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama K, Kimura S, Ohashi K, Kuwano Y. Connectin, an elastic protein of muscle. identification of “titin” with connectin. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1981;89:701–709. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minajeva A, Kulke M, Fernandez JM, Linke WA. Unfolding of titin domains explains the viscoelastic behavior of skeletal myofibrils. Biophys J. 2001;80:1442–1451. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odijk T. Stiff chains and filaments under tension. Macromolecules. 1995;28:7016–7018. [Google Scholar]

- Podgornik R, Hansen PL, Parsegian VA. Elastic moduli renormalization in self-interacting stretchable polyelectrolytes. J Chem Phys. 2000;113:9343–9350. [Google Scholar]

- Rief M, Gautel M, Oesterhelt F, Fernandez JM, Gaub HE. Reversible unfolding of individual titin immunoglobulin domains by AFM. Science. 1997;276:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Caamano S, Fernandez JM. The elasticity of individual titin PEVK exons measured by single molecule atomic force microscopy. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6261–6264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trombitas K, Granzier H. Actin removal from cardiac myocytes shows that near Z line titin attaches to actin while under tension. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C662–C670. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tskhovrebova L, Trinick J. Role of titin in vertebrate striated muscle. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B-Biol Sci. 2002;357:199–206. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tskhovrebova L, Trinick J. Properties of titin immunoglobulin and fibronectin)3 domains. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46351–46354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tskhovrebova L, Trinick J, Sleep JA, Simmons RM. Elasticity and unfolding of single molecules of the giant muscle protein titin. Nature. 1997;387:308–312. doi: 10.1038/387308a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter JC, Adams MD, Myers EW, Li PW, Mural RJ, Sutton GG, Smith HO, Yandell M, Evans CA, Holt RA. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1058040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. Sarcomere-associated cytoskeletal lattices in striated muscle. Review and hypothesis. Cell Muscle Motil. 1985;6:315–369. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-4723-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Forbes JG, Jin AJ. Single molecule measurements of titin elasticity. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2001;77:1–44. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(01)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, McClure J, Tu A. Titin: major myofibrillar components of striated muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:3698–3702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MD, Yin H, Landick R, Gelles J, Block SM. Stretching DNA with optical tweezers. Biophys J. 1997;72:1335–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78780-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Nair P, Labeit D, Kellermayer MSZ, Greaser M, Labeit S, Granzier H. Molecular mechanics of cardiac titin's PEVK and N2B spring elements. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11549–11558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200356200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson MP. The structure and function of proline-rich regions in proteins. Biochem J. 1994;297:249–260. doi: 10.1042/bj2970249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody RW. Theory of circular dichroism of proteins. In: Fasman GD, editor. Circular Dichroism and the Conformational Analysis of Biomolecules. Plenum Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki R, Berri M, Wu Y, Trombitas K, McNabb M, Kellermayer MSZ, Witt C, Labeit D, Labeit S, Greaser M. Titin-actin interaction in mouse myocardium: passive tension modulation and its regulation by calcium/S100A1. Biophys J. 2001;81:2297–2313. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75876-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]