Abstract

BACKGROUND

Surveillance and focal therapy are increasingly considered for low risk prostate cancer (PC). We describe pathological characteristics of low risk PC at radical prostatectomy in contemporary patients.

METHODS

Five-hundred-fifty-two men from 2008 to 2012 with low risk (stage T1c/T2a, PSA ≤ 10 ng/ml, Gleason score ≤6) PC underwent radical prostatectomy. Slides were re-reviewed to grade and stage the tumor, map separate tumor nodules, and calculate their volumes.

RESULTS

Ninety-three (16.9%) men had prostatectomy Gleason score 3+4=7 or higher and were excluded. Five (0.9%) men had no residual carcinoma. Remaining 454 patients composed the study cohort. The median age was 57 years (36–73) and median PSA 4.4 ng/ml (0.4–9.9). Racial distribution was 77.5% Caucasian, 15.5% African American, and 7% other. The median total tumor volume was 0.38 cm3 (0.003–7.22). Seventy percent of the patients had bilateral tumor and 34% had a tumor nodule >0.5 cm3. The index lesion represented 89% (median) of the total tumor volume. Extraprostatic extension and positive margin were present in 5.7% and 9% of cases, respectively. The tumor nodules measuring >0.5 cm3 were located almost equally between the anterior (53%) and peripheral (47%) gland. The relationship between PSA and total tumor volume was weak (r = 0.13, P = 0.005). The relationship between PSA density and total tumor volume was slightly better (r = 0.26, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

Low risk prostate cancer is generally a low volume disease. Gleason score upgrade is seen in 16.9% of cases at radical prostatectomy. While the index lesion accounts for the bulk of the disease, the cancer is usually multifocal and bilateral. Neither PSA nor PSA density correlates well with the total tumor volume. Prostate size has a significant contribution to PSA level. These factors need to be considered in treatment planning for low risk prostate cancer.

Keywords: prostate cancer, Gleason score 6, multifocality, tumor volume, PSA, PSA Density

INTRODUCTION

There is a concern that prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening has resulted in the overdetection of low risk prostate cancers (PC) that are not clinically significant [1]. Consequently, there is increasing interest in minimizing or eliminating therapy that may result in significant side effects overweighing the benefits. Men with biopsy proven low risk PC have the options of observation or focal therapy, therefore it is important to understand these patients’ pathology. There is a paucity of recent detailed histologic evaluation of low risk PC especially after the modification of Gleason grading system in 2005 [2]. As we try to identify patients that are good candidates for limited intervention, a better understanding of the underlying pathology is important. Even when there is low risk cancer on biopsy and radical prostatectomy (RP) shows Gleason score less than 3 + 4 = 7, some RPs are considered to have significant cancer based on either tumor volume or pathologic stage. This study assesses these cases with lower RP grade for tumor volume, multifocality, and location. To that end, we have performed a detailed analysis of consecutive RP specimens in men with clinically low risk PC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Low risk PC has been defined according to The National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network (NCCN) as non-palpable (stage T1c) disease with PSA <10.0 ng/ml and biopsy Gleason Score ≤6 [3]. Unlike NCCN very low risk criteria (aka Epstein criteria), any number of positive cores on extended biopsy technique (10 + cores) is allowable for a low risk group as long as other criteria are met and PSA density is not used as a factor [4]. For the years 2008–2012, we identified 552 consecutive patients with low risk PC that underwent RP at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD. All men had cancer diagnosed by transrectal ultrasound-guided template biopsy sampling bilateral apex, mid, and base medially and laterally for a total of 12 cores. More than 95% of the patients underwent RP within three months of their diagnostic or most recent biopsy. Radical prostatectomy specimens were coated with India ink, measured, and then fresh prostates were weighted without seminal vesicles. After fixation the glands were serially sectioned at 3mm intervals perpendicular to the long axis of the gland and then submitted entirely by quadrants in regular size cassettes. The sections were labeled so that they could be exactly correlated with the location in the gland.

All specimens were re-reviewed by the two pathologists on a study (ONK and JIE) to grade the tumor and evaluate extraprostatic extension (tumor into periprostatic tissue) and status of margins of resection (positive or negative). Seminal vesicle invasion was defined as tumor invading the muscular coat of the seminal vesicles. Tumor grade was determined according to the recommendations of the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) 2005 consensus conference [2].

With the mapping, we determined the location and volume of each separate tumor nodule. We described distribution of the tumor nodules as anterior, posterior, and involving both regions without characterization of the zone of origin. Each tumor nodule was assigned an individual Gleason score. Dominant tumor nodule was determined as the largest and/or highest stage tumor focus. Tumor nodules were considered spatially separate if they were ≥3mm apart in a plane of section or ≥4mm on the adjacent sections [5]. To calculate tumor volume we photocopied the slides with mapped tumor in a background of 1mm grid magnifying the copy at 1.5 times (for ease of counting) and counted the number of square millimeters in each tumor nodule. To convert this into cubic millimeters we multiplied the total number of square millimeter in each tumor nodule by 3 (thickness of the tissue in a block) and by 1.12 (fixation shrinkage factor). Cubic millimeters were then converted into cubic centimeters [6]. PSA density (PSAD) was calculated by dividing preoperative PSA level by the prostate weight [7]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the patient weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2). We correlated the volume and location of the tumor nodule(s) with PSA, PSAD, race, and BMI. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Statistical Methods

Categorical outcomes were summarized with counts and percentages, and continuously distributed outcomes were summarized with the sample size, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum. We used Pearson’s correlation to assess relationships between continuously distributed outcomes expressed in log units. Subgroups were contrasted on continuous outcomes with Mann–Whitney U test. All statistical testing was two-sided with a significance level of 5%. We used R Version 2.15.3 throughout (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Ninety-three (16.9%) men had prostatectomy Gleason score 3 + 4 = 7 or higher and were excluded because by definition had adverse features based on Gleason score alone. Five (0.9%) men had no residual carcinoma at RP following a recommended examination protocol for such cases [8]. Remaining 454 patients composed the study cohort in whom detailed morphologic analysis of cancer at RP was performed. The median age was 57 years (36–73 years). The median PSA was 4.4 ng/ml (0.4–9.9 ng/ml). The Caucasians composed 77.5% (n = 352), 15.5% (n = 70) were African Americans, 1% (n = 6) were Asian men, and the race was not recorded in 26 (6%) individuals. The median BMI was 27.1 (15.9–43.9). The median prostate weight was 43.8 g (19.71–187 g) without seminal vesicles. The median total tumor volume was 0.38 cm3 (0.003–7.22 cm3) and 137 (30.2%) patients had unilateral tumor (69.8% bilateral tumors). Focal extraprostatic extension was found in 3.5% and non-focal in 2.2% of specimens. Nine percent had positive resection margin. None of the cases had seminal vesicle invasion. Pelvic lymph nodes were dissected in 453 (99.8%) cases and had no metastasis. The primary and secondary Gleason patterns were 3 in all the patients, but 26% had tertiary pattern 4 (<5% of tumor nodule volume). While this minor component of pattern 4 may in isolated cases have different biologic significance [9], most cases behave similar to pure Gleason score 3 + 3 = 6 cancers and in contemporary practice tertiary pattern is not included in postoperative nomograms so that such patients are followed as Gleason score 6 disease. For this reason we retained these men in the study group. The median PSAD was 0.10 ng/ml/cc (0.01–0.26). One hundred forty two (31.3%) patients had a single tumor nodule and 312 (68.7%) had multiple. One hundred sixty three patients (35.9%) had two separate tumor nodules, 116 (25.5%) had 3, and 33 (7.3%) had 4. One hundred ninety one patients (42%) had a total tumor volume >0.5 cm3. Thirty four percent had a tumor nodule ≥0.5 cm3 (including the 2% that had two tumor nodules ≥0.5 cm3). There were 52 patients with an isolated single lesion ≥0.5 cm3. The tumor nodules measuring >0.5 cm3 were almost as commonly located in the anterior prostate (53%) as they were in the peripheral zone (47%). The median volume of the largest tumor nodule was 0.29 cm3 (0.003–7.0 cm3), whereas the second largest lesion (if existed) had a median volume of 0.05 cm3 (0.003–1.12 cm3). The largest lesions represented on average 89% (median; 83% mean) of the total tumor volume (34%–100%). Overall, the index lesion was located in the anterior gland 30% of the time, the posterior (peripheral) gland 61% of the time, and involved both the anterior and posterior gland in 9% of the patients.

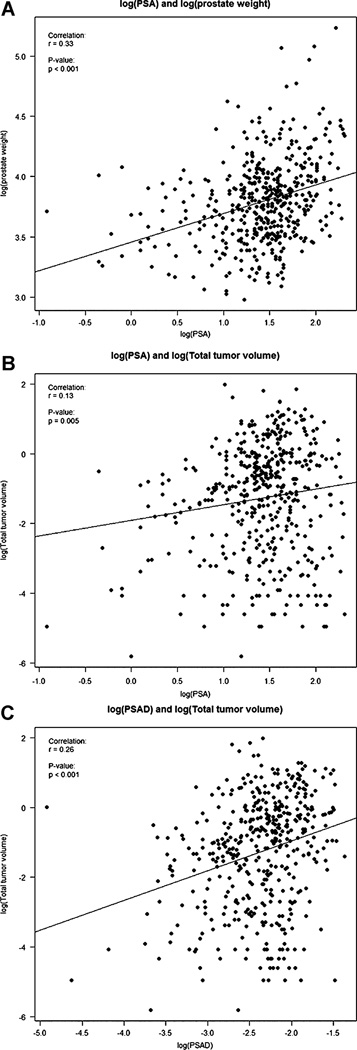

We did an extensive evaluation of PSA and PSAD versus prostate weight and total tumor volume. Overall, PSA increased in larger prostates (r = 0.33, P < 0.001) as indicated by the least square line in Figure 1A. The correlations between PSA and total tumor volume (r = 0.13, P = 0.005; Fig. 1B), PSAD and total tumor volume (r = 0.26, P < 0.001; Fig. 1C), and between BMI and prostate weight (r = 0.25, P < 0.001) were statistically significant. The correlations between BMI and PSA (0.06, P = 0.26) and BMI and total tumor volume (r = 0.01, P = 0.89) were not significant. The median PSA, prostate weight, total tumor volume, and volume of the dominant tumor nodule did not vary significantly between the race groups.

Fig. 1.

A. Correlation of log(PSA) and log(prostate weight), r = 0.33; P < 0.001. B. Correlation of log(PSA) and log(total tumor volume), r = 0.13; P = 0.005. C. Correlation of log(PSA density[PSAD]) and log(total tumor volume), r = 0.26; P < 0.001.

We arbitrarily evaluated the relationship between PSA and tumor volume for patients with PSA ≥4.0 and >4.0 ng/ml (Table I). There was a significant difference in tumor volume (P = 0.02) and more statistically significant difference in prostate weight and PSAD (P < 0.001, both). The correlation between PSA and total tumor volume for patients with lower PSA was r = 0.26, P < 0.001 (Table II). For patients with higher PSA the correlation was not significant (P = 0.15). The relationship between PSAD and total tumor volume was stronger for patients with PSA ≤0.4 ng/ml (r = 0.4, P < 0.001) and kept its significance for those with PSA >4.0 ng/ml (r =0.2, P = 0.001).

TABLE I.

Prostatectomy Findings

| Variable | PSA ≤ 4 (n = 188) | PSA > 4 (n = 266) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total tumor volume | 0.02a | ||

| N | 186 | 264 | |

| Mean ± SD | 0.56 ± 0.82 | 0.8 ± 1 | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 0.32 (0.09, 0.69) | 0.47 [0.09, 1.01] | |

| Min, max | 0, 7.22 | 0.01, 6.32 | |

| Prostate weight | <0.001a | ||

| N | 187 | 264 | |

| Mean ± SD | 42.8 ± 14.5 | 50.7 ± 21.7 | |

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 40.7 (32.4, 50.4) | 46.3 [37.2, 57.3] | |

| Min, Max | 19.7, 102 | 22, 187 | |

| PSA density | <0.001a | ||

| N | 187 | 265 | |

| Mean ± SD | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | |

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 0.07 (0.05, 0.09) | 0.12 (0.1, 0.15) | |

| Min, max | 0.01, 0.17 | 0.01, 0.26 |

Mann–Whitney U test.

TABLE II.

Correlation of PSA and PSA Density (PSAD) With Total Tumor Volume (TV)

| Correlation | PSA ≤ 4 | PSA > 4 |

|---|---|---|

| PSA versus TV | r = 0.26, P < 0.001 | r = −0.09, P = 0.15 |

| PSAD versus TV | r = 0.4, P < 0.001 | r = 0.2, P = 0.001 |

DISCUSSION

There is a paucity of studies evaluating the pathologic characteristics of PC with the detailed analysis of the prostate submitted entirely for histologic evaluation. This may be due to the fact that it is very labor intensive and is limited to academic institutions with high volume PC programs with dedicated genitourinary pathologists. In the current study, we have described the pathologic characteristics in contemporary patients with NCCN low risk PC (PSA <10 ng/ml, T1c, biopsy Gleason score 3 + 3 = 6). Overall, the goal of this manuscript is to describe that even in men with low Gleason score (i.e., 3 + 3 = 6) RP there may be significant disease defined by either tumor volume (>0.5 cm3) or stage (pT3a or pT3b). We believe these are important factors to convey that it is not only Gleason score, but other factors even in low risk disease may qualify patients as having significant cancer for either focal therapy or surveillance. The patients with Gleason score 3 + 4 = 7 and above at RP were excluded from the analysis because those are significant cancers by grade regardless of other findings. Moreover, such NCCN low risk patients whose RP revealed a higher grade cancer were described recently in a study validating the original and modified Epstein criteria in contemporary patients [10].

In the PSA screening era, there is an interest in determining whether some of the newly discovered non-palpable (T1c) biopsy proven Gleason score 3 + 3 = 6 PCs are in fact not significant, that is, pose no risk to the patients if no definitive therapy is applied. One approach has been to evaluate the volume of the cancer in relation to findings of high risk for spread, such as extraprostatic extension, seminal vesicle involvement, and positive surgical margin. A significant early study on the prevalence of clinically unsuspected PC was performed by Stamey et al. [11] The authors evaluated 139 patients undergoing cystoprostatectomy for non-prostate cancer reasons and found 55 (40%) harbored PC. This was at the beginning of the PSA era, so only about half of these patients had a pre surgery PSA measured. It is possible the number of unsuspected cancers would have been lower if they all had been prescreened, but only eight had a cancer larger than 0.5 cm3. Their premise was that although unsuspected PC was found frequently at autopsy, their evaluation of the epidemiological data showed that only 8% of living men would actually be diagnosed with clinically significant PC. From their cohort, they calculated that the 8% breakpoint based on cancer size was 0.5 cm3. The implication being that if the cancer was less than that size (or there was no cancer at that time), then it would have not become clinically significant in the patients’ lifetime. A more recent study reported a similar estimated threshold [12]. In a subgroup of patients undergoing prostatectomy for cancer detected in the Rotterdam screening program, a microsimulation model for this population calculated the life-time risk of diagnosed and clinically significant PC. In that model, the thresholds for significant tumors were 0.7 cm3 for the total tumor volume and 0.55 cm3 for the index lesion [12].

As part of their initial analysis, Stamey’s group found that few patients actually had cancers that small [11]. They went back and looked at 408 prostatectomies in the early PSA era and only 37/408 (9%) had cancers <0.5 cm3. A slightly more recent study showed the overall incidence of <0.5 cm3 cancers to be 4% [13]. Others showed that even when selecting for clinically non-palpable patients, only 19% had tumors less than 0.5 cm3 [14].

It’s possible that the 0.5 cm3 size may be overly conservative, which Noguchi et al. later acknowledged [15]. Using extraprostatic extension as a harbinger of risk, Dugan showed that no cancer less than 1.74 cm3 had this finding [13]. In the earlier series from The Johns Hopkins, no patient with a volume <0.5 cm3 recurred, although 13% had extraprostatic extension [7]. Later analysis seemed to confirm that 0.5 cm3 was a very reliable cut point [16], which, as we noted above, has been confirmed by others [12].

In our more modern cohort, looking at defined low risk patients, we found that a larger percentage of patients (58%) had a total tumor volume <0.5 cm3 and 66% had their dominant tumor less than that size. This may partially be explained by our exclusion of those men with Gleason upgrade at RP, but the implications are that in this modern cohort, if 0.5 cm3 is truly a measure of tumors that are significant, a large number of low risk PC patients could possibly be spared or delayed a definitive treatment.

An interesting finding is that most of our patients (68.7%) had multiple tumor nodules, but very few (2%) had more than one tumor nodule larger than 0.5 cm3. This is identical to Wolters’ et al data, where 68% of cancers were multifocal [12]. In Cheng’s et al. whole mount series of patients with <0.5 cm3 cancer volume, 69% were multifocal [17]. There was no extraprostatic extension and only 5% had positive margins. Overall, the cancer distribution in their patients was much more likely to be in the posterior gland (84%) than the anterior (16%). Our findings were somewhat similar in that the index (largest) lesion was peripheral 61%, anterior 30%, and extended to both zones 9% of the time. Elgamal et al in their T1c whole mount series reported an almost equal distribution between transition/anterior zone cancers (46%) and peripheral zone cancer (54%) [14] which we saw in the clinically significant (>0.5 cm3) lesions. In the earlier cohort of T1c patients from The Johns Hopkins, only 15% of the patients had anterior cancers with most having peripheral tumors (80%) [7]. Noted is that the median PSA was higher (8.1 ng/ml) and 38% of patients had PSA >10 ng/ml in that study. Interestingly, in the recent 2 studies performed in the same institution by two of the current authors (ONK and JIE) in individuals with NCCN clinically low and very low risk PC, the dominant anterior tumor was seen in around 29% of Caucasians and 44% – 51% of African American individuals making the contemporary surveillance criteria less reliable in the latter cohort. (10,18) We limited the current analysis to RP specimens of patients with NCCN low risk PC, but are uncertain whether that could account for the difference in tumor distribution.

Conceptually, if we consider that PSA produced by a given volume of benign prostatic tissue is fairly constant, then with the same amount of cancer the total PSA will be more representative of the cancer volume in smaller glands and less so in larger. Our findings are supportive of this. Overall, in this selected low risk cancer cohort PSA has shown a weaker association with the total tumor volume (r = 0.13; P = 0.005) than with the prostate weight (r = 0.33; P < 0.001). In patients with PSA ≤4.0 ng/ml, the correlation between PSA and tumor volume was significant compared to patients with PSA >4.0 ng/ml. While there was a borderline significant difference in total tumor volume (P = 0.02), the difference in prostate weight was strongly significant (P < 0.001). PSAD showed a better correlation with the tumor volume in patients with lower PSA (r = 0.4) and maintained its significance in patients with PSA >4 ng/ml. In a recent work we have shown a comparable superiority of PSAD in predicting cancer volume in NCCN low risk patients [10]. Our inability to show a stronger correlation between the cancer volume and PSA and PSAD was probably hampered by the overall small cancer volumes. Another clinical implication is that serum PSA levels approaching limit values of NCCN low risk criteria (i.e., 8–9.9 ng/ml) in men with T1c Gleason score 3 + 3 = 6 disease may be attributed to a larger prostate volume in a subset of patients. PSAD appears to be able to resolve this challenge warranting its role as one of the criteria in contemporary PC surveillance algorithms [7,10,18].

In summary, 16.9% of men with low risk PC on biopsy have higher grade cancer at RP. In 0.9% of men no residual disease is identified at RP. For the remaining 82.2% of men with low risk PC on biopsy with Gleason score 6 at RP, tumor nodules of significant clinical size (>0.5 cm3) are just as likely to be anterior as posterior. More than half of the patients (58%) have a total tumor volume of <0. 5 cm3, but more patients have multiple tumor nodules and bilateral disease with 66% of the patients in whom dominant tumor nodules are <0. 5 cm3. Neither PSA nor PSA density correlates well with the total tumor volume in this cohort with overall low volume disease. Prostate size has a significant contribution to PSA level. These factors need to be considered in planning for low intervention and surveillance approaches in low risk PC.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ganz PA, Barry JM, Burke W, Col NF, Corso PS, Dodson E, Hammond ME, Kogan BA, Lynch CF, Newcomer L, Seifter EJ, Tooze JA, Viswanath K, Wessells H. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference: Role of active surveillance in the management of men with localized prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:591–595. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-8-201204170-00401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Jr, Amin MB, Egevad LL. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1228–1242. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173646.99337.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohler J, Bahnson RR, Boston B, Busby JE, D’Amico A, Eastham JA, Enke CA, George D, Horwitz EM, Huben RP, Kantoff P, Kawachi M, Kuettel M, Lange PH, Macvicar G, Plimack ER, Pow-Sang JM, Roach M, 3rd, Rohren E, Roth BJ, Shrieve DC, Smith MR, Srinivas S, Twardowski P, Walsh PC. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:162–200. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tosoian JJ, JohnBull E, Trock BJ, Landis P, Epstein JI, Partin AW, Walsh PC, Carter HB. Pathological outcomes in men with low risk and very low risk prostate cancer: Implications on the practice of active surveillance. J Urol. 2013;190:1218–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wise AM, Stamey TA, McNeal JE, Clayton JL. Morphologic and clinical significance of multifocal prostate cancers in radical prostatectomy specimens. Urology. 2002;60:264–269. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hussain TO, Epstein JI. Initial high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia with carcinoma on subsequent prostate needle biopsy: Findings at radical prostatectomy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1165–1167. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182206da8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein JI, Walsh PC, Carmichael M, Brendler CB. Pathologic and clinical findings to predict tumor extent of nonpalpable (stage T1c) prostate cancer. JAMA. 1994;271:368–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffield AS, Epstein JI. Detection of cancer in radical prostatectomy specimens with no residual carcinoma in the initial review of slides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:120–125. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318185723e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross HM, Kryvenko ON, Cowan JE, Simko JP, Wheeler TM, Epstein JI. Do adenocarcinomas of the prostate with Gleason score (GS) ≤ 6 have the potential to metastasize to lymph nodes? Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1346–1352. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182556dcd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kryvenko ON, Carter HB, Trock BJ, Epstein JI. Biopsy criteria for determining appropriateness for active surveillance in the modern era. Urology. 2014;83:869–874. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stamey TA, Freiha FS, McNeal JE, Redwine EA, Whittemore AS, Schmid HP. Localized prostate cancer. Relationship of tumor volume to clinical significance for treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:933–938. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3+<933::aid-cncr2820711408>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolters T, Roobol MJ, van Leeuwen PJ, van den Bergh RC, Hoedemaeker RF, van Leenders GJ, Schroder FH, van der Kwast TH. A critical analysis of the tumor volume threshold for clinically insignificant prostate cancer using a data set of a randomized screening trial. J Urol. 2011;185:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dugan JA, Bostwick DG, Myers RP, Qian J, Bergstralh EJ, Oesterling JE. The definition and preoperative prediction of clinically insignificant prostate cancer. JAMA. 1996;275:288–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elgamal AA, Van Poppel HP, Van de Voorde WM, Van Dorpe JA, Oyen RH, Baert LV. Impalpable invisible stage T1c prostate cancer: Characteristics and clinical relevance in 100 radical prostatectomy specimens–a different view. J Urol. 1997;157:244–250. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noguchi M, Stamey TA, McNeal JE, Yemoto CM. Relationship between systematic biopsies and histological features of 222 radical prostatectomy specimens: Lack of prediction of tumor significance for men with nonpalpable prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;166:104–109. discussion. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein JI, Chan DW, Sokoll LJ, Walsh PC, Cox JL, Rittenhouse H, Wolfert R, Carter HB. Nonpalpable stage T1c prostate cancer: Prediction of insignificant disease using free/total prostate specific antigen levels and needle biopsy findings. J Urol. 1998;6:2407–2411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng L, Jones TD, Pan CX, Barbarin A, Eble JN, Koch MO. Anatomic distribution and pathologic characterization of small-volume prostate cancer (<0.5 ml) in whole-mount prostatectomy specimens. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1022–1026. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundi D, Kryvenko ON, Carter HB, Ross AE, Epstein JI, Schaeffer EM. Pathological examination of radical prostatectomy specimens in men with very low risk disease at biopsy reveals distinct zonal distribution of cancer in black american men. J Urol. 2014;191:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]