Abstract

Developmental processes and their results, morphological characters, are inherited through transmission of genes regulating development. While there is ample evidence that cis-regulatory elements tend to be modular, with sequence segments dedicated to different roles, the situation for proteins is less clear, being particularly complex for transcription factors with multiple functions. Some motifs mediating protein-protein interactions may be exclusive to particular developmental roles, but it is also possible that motifs are mostly shared among different processes. Here we focus on HoxA13, a protein essential for limb development. We asked whether the HoxA13 amino acid sequence evolved similarly in three limbless clades: Gymnophiona, Amphisbaenia and Serpentes. We explored variation in ω (dN/dS) using a maximum-likelihood framework and HoxA13sequences from 47 species. Comparisons of evolutionary models provided low ω global values and no evidence that HoxA13 experienced relaxed selection in limbless clades. Branch-site models failed to detect evidence for positive selection acting on any site along branches of Amphisbaena and Gymnophiona, while three sites were identified in Serpentes. Examination of alignments did not reveal consistent sequence differences between limbed and limbless species. We conclude that HoxA13 has no modules exclusive to limb development, which may be explained by its involvement in multiple developmental processes.

Keywords: development, evolution, HoxA13, molecular signatures, limblessness

Introduction

Evolution of morphological diversity has fascinated biologists, but only in the past half-century the investigation of mechanisms underlying the origin and establishment of specific phenotypes became possible through the combination of genetics, evolution and developmental biology in the field so-called Evo-Devo (Evolution of Development, see Raff, 2000; Hall, 2012). Consolidation of Evo-Devo fostered the search for variations in developmental processes likely responsible for the distribution of heritable phenotypic variance that potentially could be molded by natural selection (Brakefield, 2006; 2011).

Differences in gene expression during developmental processes often can be explained by sequence variation in cis-regulatory elements but coding region variations of transcription factors are also a possible source of developmental variation. Mutations in cis-regulatory elements have been argued to be a more likely source of adaptive genetic variation, a trend that is often found when investigating cis-regulatory evolution for phenotypic divergence (Stern, 2000; Wray, 2007; Mansfield, 2013). Recent studies, however, provide a wide range of evidence supporting the contribution of mutations in coding regions of transcription factor genes for the diversification of phenotypes (Galant and Carroll, 2002; Lynch et al., 2008, Crow et al., 2009; Brayer et al., 2011). Such findings imply that transcriptions factors do not remain functionally equivalent during evolution (Galant and Carroll, 2002; Ronshaugen et al., 2002; Lynch et al., 2008; Crow et al., 2009), and that the adaptive evolution of transcription factors proteins may be involved in the origin of new phenotypes (Lynch et al., 2004; Lynch and Wagner, 2008; Crow et al., 2009; Brayer et al., 2011). A disparity emerging from current literature is that there is ample evidence that cis-regulatory elements tend to be modular, with dedicated sequence segments for different developmental roles, but the role of transcription factor proteins is more complex due to the potential for pleiotropic constraints. Discussions about sequence modules dedicated to specific developmental roles in transcription factor proteins is particularly complex for homeotic proteins involved in multiple functions, and two alternative scenarios emerge (Sivanantharajah and Percival-Smith, 2015): there may be specific motifs mediating protein-protein interactions that are exclusive to particular developmental roles, while other motifs within the same protein are shared among different developmental processes, for instance the highly conserved homeodomain. In the second scenario, changes in a given sequence segment that plays two developmental roles likely affect both processes, as well as their results (i.e. the morphological characters established in the developing embryo), so that any motif involved in multiple developmental processes would be expected to be under pleiotropic constraint (for recent discussions about the topic see Pavlicev and Wagner, 2012; Pavlicev and Widder, 2015).

The counterpoint between the presence of motifs dedicated to specific developmental roles and a pleiotropic constraint that may be imposed by the commitment of some motifs to multiple functions may be investigated through combination of two approaches: 1) a transcription factor protein known to be involved in more than one developmental process, and 2) a phylogenetic framework where one developmental process was suppressed but another remains effective in the organism. HOX proteins emerge as good candidates because they play central roles during embryo development in the specification of structures along the vertebrate anterior-posterior body axis, and have also acquired several functions including development of limbs and the urogenital system (Hsieh-Li et al., 1995; Taylor et al., 1997; Kobayashi and Behringer, 2003; Sivanantharajah and Percival-Smith, 2015). The transcription factor HoxA13, in particular, is essential for several functions (Fromental-Ramain et al., 1996; Innis et al., 2002; Shou et al., 2013): during limb development it regulates formation of digits, phalangeal joints and carpal/tarsal elements (Stadler et al., 2001; Knosp et al., 2004, 2007; Perez et al., 2010); during organogenesis, it modulates development of digestive and urogenital tracts, including differentiation of the mammalian female reproductive system (Taylor et al., 1997). Moreover, there is evidence for pleiotropy effects on HoxA13 and mutations in this gene simultaneously affect the development of the urogenital system and the limbs (Mortlock and Innis, 1997; Goodman et al., 2000). Specifically, in mice a 50 base-pair deletion at the first exon of HoxA13 results in hypodactyly (Mortlock et al., 1996), while the expansion of an N-terminal polyalanine in this first exon is associated with limb and genitourinary abnormalities in humans (Goodman et al., 2000).

A good evolutionary scenario to test for the presence of sequence segments exclusively dedicated to a given function in the pleiotropic HoxA13gene is the recurrent evolution of limbless morphologies in basal lineages of Tetrapoda. Evolution of snakelike morphologies in Lepidosauria and Lissamphibia is characterized by body elongation and limb loss (Woltering, 2012). In this scenario, the presence and identity of limb-specific sequence segments in the protein would be supported by identification of sequence changes in HoxA13 that are common to different limbless lineages. In contrast, the likelihood that all motifs involved in limb development are also committed to other developmental functions would receive support if it is found that there are no consistent sequence differences between limbed and limbless species. In the present study we compared the molecular sequence variation of HoxA13 among three tetrapod snakelike lineages that independently lost limbs: Serpentes, Amphisbaenia and Gymnophiona. We used both likelihood-ratio tests implemented in PAML (Yang, 2007) and visual inspections of the alignments to compare HoxA13 sequences among these three snakelike lineages.

Material and Methods

Tissue samples were obtained from Museum Herpetological Collections or Private Zoological Collections, and the molecular database for HoxA13assembled was complemented with sequences available at GenBank (see Table S1). Genomic DNA was extracted from the tissue samples using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. In this study we focused on the first exon of HoxA13 due to described phenotypic effects of mutations in this region and the general conservation of the homeodomain which is coded for in exon 2 (Mortlock et al., 1996; Goodman et al., 2000). Gene fragments of HoxA13 exon-1 (375 to 455 bp), were amplified from one individual of each species using the following conditions: 50 to 100 ng of DNA and primers at 10 μM concentration combined with PCR Master Mix (Reddymix, 2.5 mM MgCl2; Abgene, Inc.) to a final reaction volume of 50 μL; thermocycling conditions consisted of 30 or 35 cycles (1 min at 94 °C, 1 min of annealing at 48–52 °C, 1 min at 72 °C), followed by a terminal extension step (5 to 8 min at 72 °C). Primers used to amplify Hoxa13 were synthesized based on sequences from Mortlock et al. (2000), as follows:

F1, 5-CTATGACAGCCTCCGTGCTC-3;

F2, 5-ATCGAGCCCACCGTCATGTTTCTCTACGAC-3;

R1, 5-CGAGCTCTGTGCCGTCGCCGAGTAGGGACT-3;

R2, 5-TGGTAGAAAGCAAACTCCTTG-3.

The PCR products were gel-purified using the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean- up System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Genes were cloned using the pGEM-T vector system (Promega) and E.coli -competent cells (DH5α). Three to eight clones of each species were sequenced to control for errors during PCR amplification. Sequencing was performed in both directions with the vector primers T7 and SP6 (sequence according to technical manual pGEM-T Vector System-Promega), using an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

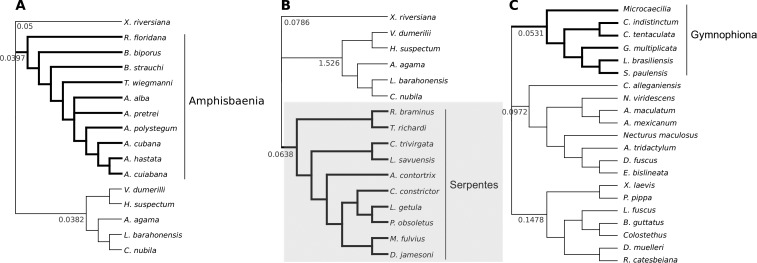

In total, we sequenced HoxA13 from 23 species of Squamata and Lissamphibia, and downloaded 24 additional HoxA13 sequences from GenBank. All sequences obtained were aligned using ClustalW algorithm (Thompson et al., 1994) implemented in the software BioEdit sequence alignment editor, and the alignment was manually improved based on amino acid translated sequences. The alignment was first visually inspected for indels, and no conspicuous patterns common to all three snakelike lineages were identified. In order to investigate natural selection acting on the sequence of HoxA13 exon-1 in the three snakelike lineages that represent independent limb losses, we performed molecular evolution analyses in three separate data sets (Figure 1): A) limbed lizards versus Amphisbaenia; B) limbed lizards versus Serpentes; C) limbed amphibians (anurans and salamanders) versus Gymnophiona (caecilians). Such analyses are implemented under a phylogenetic framework, so we adopted the phylogenetic hypothesis proposed by Pyron et al.(2013) for Squamata and that proposed by Pyron and Wiens (2011) for Lissamphibia.

Figure 1. Topology used for test models of molecular signatures of HoxA13 in limbless lineages. The models of molecular signatures of HoxA13 were tested in the three main comparisons. A) limbed lizards versus Amphisbaenia; B) limbed lizards versus Serpentes; C) limbed amphibians (anurans and salamanders) versus Gymnophiona. The tree to conduct the analyses of variable ω among lineages and sites is based on published literature (Pyron et al., 2013 for Squamata and Pyron and Wiens. 2011 for Lissamphibia). The bold branches correspond to the groups labeled as ‘foreground branches’. The shaded tree represents the one where the branch-site model identified signatures of positive selection. The values represented in each branch correspond an independent ω ratio that corresponds to ratio of the rate of non-synonymous substitutions (dN) to the rate of synonymous substitutions (dS) in a maximum likelihood framework.

In order to investigate the possible roles of relaxed or directional selections on the evolution of HoxA13 in the limbless lineages, we explored the variation in ω, the ratio of the rate of non-synonymous substitutions (dN) to the rate of synonymous substitutions (dS), in a maximum likelihood framework using the codeml program implemented in PAML (Yang, 2007). In these tests, indels were deleted, so that only portions of the alignment that were unambiguous were used for the dN/dS analyses. We conducted the “free ratio” branch model (Model 1), which assumes an independent ω ratio for each branch. Although very effective, this test is generally conservative once this approach averages substitution rates over all amino acid sites in the sequence (Bamshad and Wooding, 2003). As most amino acid sites are expected to be highly conserved and adaptive evolution most likely affects only a few sites, we also applied the branch-site model that estimates rates of evolution in a codon-by-codon basis on a specific branch of the tree. In addition, with this model we could test whether the limbless lineages share common sites under positive selection that could have evolved convergently. In that sense, models of molecular signatures representing directional selection or neutral evolution were tested in the HoxA13 of snakes, amphisbaenians and caecilians using the branch-site model A implemented in PAML (Zhang et al., 2005; Yang, 2007). This model tests for positive selection on individual sites along a specific lineage of the tree, called foreground branch, where the other lineages are background branches. In our case, the limbless lineages were labeled as fore-ground branches as depicted on Figure 1. In this method, codon sites are categorized into four classes 0, 1, 2a, and 2b with respective proportions of p0, p1, p2a, and p2b. In site class 0, negative selection is assumed on both the foreground and background branches, with 0 < ω0 < 1. In site class 1, codons are assumed to evolve neutrally in all lineages, with ω1 = 1. In class 2a, it is assumed that positive selection operates on the foreground branch with ω2 > 1, and that negative selection operates on the background branches, with ω = ω0. Finally in class 2b, positive selection is allowed on the foreground branch with ω2 > 1, but no selection is assumed for the background branches. The corresponding null model is the same as model A, except that no selection is assumed on the foreground branch in classes 2a and 2b, and ω2 is fixed to 1. The nested models were compared using the likelihood-ratio test (LRT), and the level of significance was 0.05. If the null hypothesis is rejected, a Bayes empirical approach is used to calculate the posterior probabilities that each site has evolved under positive selection on the foreground lineage (Yang et al., 2005). Each branch-site model was run multiple times, with three starting ω values (0.5, 1, and 2) to check the existence of multiple local optima, as recommended.

Because the branch-site model implemented in PAML can be limiting due to the necessary specification of foreground lineages and the assumption that ω = 1 for all background lineages (Zhang et al., 2005), we also examined HoxA13 for signatures of episodic selection using the mixed model of evolution (MEME, Murrell et al., 2012) and the fixed-effect likelihood (FEL) model of molecular evolution performed with HyPhy in Datamonkey server (Delport et al., 2010). The FEL model estimates the ratio of dN/dS on a site-by-site basis, without assuming an a priori distribution across sites. The MEME model allows the distribution of the estimated ω value to vary among sites and branches, and identifies episodes of positive selection that affect only a subset of lineages.

Results

We sequenced the exon-1 of HoxA13 in a total of 23 species, being five species of Amphisbaenia, seven of Caudata, five of Gymnophiona, and six of Anura (see details in Supplementary Table S1). The database was complemented with 24 published sequences of HoxA13 downloaded from GenBank: five species of Amphisbaenia and six of limbed lizards, ten snake species, one species of Caudata, one of Gymnophiona and one of Anura (details given in Supplementary Table S1). Analyses of HoxA13 molecular evolution were implemented as follows: (1) limbed lizards versus Amphisbaenia (Figure 1A); (2) limbed lizards versusSerpentes (Figure 1B); and (3) limbed amphibians versus Gymnophiona (Figure 1C). To address the global evolutionary pressure acting on the HoxA13 gene in these lineages we obtained their ω (dN/dS) throughout the model M1 (“free model”) in the branch model. The ω values obtained for limbless lineages are much lower than the neutral rate and ranged from 0.0397 to 0.0638 (Figure 1), being equal or lower than the corresponding values of the other lineages (0.0382 to 1.526). These values indicate that HoxA13 in the limbless lineages experienced strong purifying selection, even when “released” from one important function (limb and digits formation).

To investigate whether there are sites under positive selection and to determine whether some amino acid sites could have undergone convergent contributions to developmental changes in the limbless lineages, we applied the robust branch-site model. The likelihood-ratio tests (LRTs) support the model of adaptive evolution in HoxA13 only in Serpentes, while in Amphisbaenia and in Gymnophiona the fit of the null model for neutral evolution was not significantly different than the alternative model (Table 1). The evidence for positive selection in HoxA13detected by the branch-site model indicates that, when the stem lineage of Serpentes was labeled as foreground branch, the model estimating a class of sites with a ω value greater than 1 (model A) had a significantly better fit than the null model (Table 1). In this model, three codons were identified as being under positive selection in HoxA13 only in the Serpentes lineage: sites 46, 88 and 121 (Table 1). Models of non-neutral evolution were not supported in amphisbaenians and caecilians, as the likelihoods of a branch-site model and the null one were not statistically different in these lineages (Table 1), indicating that limb loss did not imprint consistent sequence differences onto the HoxA13 gene between limbed and limbless lineages.

Table 1. Summary of likelihood-ratio tests performed using branch-site models implemented in PALM. Log-likelihood values of different models tested using Amphisbaena, Serpentes or Gymnophiona labeled as foreground branches. LnL corresponds to the likelihood value. Sites inferred under positive selection in Serpentes had posterior probabilities values of 0.64, 0.76 and 0.51, respectively.

| Foreground branch | Model | LnL | LRT | p | Positively selected sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serpentes | Model A | −1620.1549 | 3.967 | 0.046 | 46, 88, 121 |

| Null | −1622.1386 | ||||

| Amphisbaenia | Model A | − 1287.5078 | 0 | > 0.05 | - |

| Null | − 1287.5078 | ||||

| Gymnophiona | Model A | −1777.4047 | 0 | > 0.05 | - |

| Null | −1777.4047 |

The absence of consistent sequence differences in HoxA13 between limbed and limbless lineages was also corroborated in the analyses performed using MEME, where we identified episodic positive selection only in codon 66 in the ancestral lineage of all snakes, and in two amphisbaenian species (A. polystegum and A. cuiabana), as shown in the Supplementary Figure S1. This codon was not the same identified in Serpentes by the branch-site model implemented in PAML; the FEL model did not identify any codon under positive selection in our dataset.

Discussion

This study investigated whether there are limb-specific sequence elements in the transcription factor protein HoxA13. We used as model system the recurrent independent evolution of limbless lineages within Tetrapoda. In this framework, identification of molecular signatures in HoxA13 that are common to independently derived limbless lineages would suggest the presence of limb-specific sequence segments in the protein, while no consistent sequence differences between limbed and limbless species suggests that all motifs involved in limb development are also committed to other developmental functions. The conceptual basis underpinning the first prediction relies on evidence that genetic elements dedicated to the development of a particular structure tend to get lost when the corresponding structure is lost in evolution (Graur and Li, 1999), as observed in the loss of pelvic spines in lake morphs of sticklebacks (Bell, 1987) and of penile spines in humans (Reno et al., 2013). In these examples, a dedicated cis-regulatory element has been lost in evolution coincidentally with the loss of the morphological structure, suggesting the existence of sequence modules dedicated to specific developmental processes. We apply this reasoning to coding regions and investigated amino acid sequence variation in the first exon of HoxA13 to test for specific amino acid sequence motifs in transcription factor proteins that may be exclusively dedicated to certain biological roles.

Analyses of molecular evolution in the pleiotropic HoxA13 gene were applied to the evolutionary scenario of recurrent evolution of limbless tetrapod lineages, here represented by three snakelike clades (see Woltering, 2012): Gymnophiona (Lissamphibia), Amphisbaenia and Serpentes (Lepidosauria). We investigated the overall constraint, the site-specific evolutionary rates, and evidence of positive selection acting on HoxA13. None of our analyses revealed a signal specific to and shared by the three snakelike clades investigated. Specifically, our comparisons of evolutionary models based on likelihood-ratio tests provided low global values of ω, and the branch-site model failed to detect evidence of positive selection acting on any site along the branch leading to the Amphisbaenia and the Gymnophiona lineages, identifying three sites evolving under positive selection of HoxA13only in snakes. From these results we conclude that the first exon of HoxA13 does not have limb-specific sequence motifs, and propose that all protein-protein interaction motifs of the HoxA13 protein necessary for limb development are also involved in the establishment of other structures. Nonetheless, we recognize that HoxA13 limb-specific motifs may actually exist although remaining unidentified under the approach used here, though unlikely given the sequence evidence presented in this study. There could still be limb-specific motifs in the C-terminal tail that is coded for by exon 2 and which is not covered by the data analyzed here.

Evolution of snakelike tetrapods involves interlocked changes in different traits: limb reduction/loss occurs simultaneously with body elongation (Gans, 1975; Lande, 1978). Two major clades represented here, Lepidosauria and Lissamphibia, differ in the evolutionary patterns of such morphological transitions. Lissamphibia has fewer independent events of snakelike evolution (three transitions in salamanders [Parra-Olea and Wake, 2011] plus the origin of Gymnophiona [Pyron and Wiens, 2011; San Mauro et al., 2014]) when compared to Lepidosauria (at least 26 independent origins; Wiens et al., 2006). These transitions likely involved changes in genes underlying the development of the modified structures. For example, snakelike organisms exhibit an acceleration of the somitogenesis clock rhythm, a delay in the shrinkage of pre-somitic mesoderm (PSM), changes in expression domains of Hox genes, and a differential interpretation of Hox codes by downstream genes in the pre-caudal region (Cohn and Tickle, 1999; Woltering et al., 2009; Di-Poï et al., 2010; Woltering, 2012). These modifications in developmental processes culminate on increased numbers of vertebrae and the consequent body elongation, as well as a vertebral deregionalization associated with limb loss (Woltering, 2012; but see Head and Polly, 2015). Variation in expression domains of Hox genes is particularly relevant in this context because Hox proteins are essential for morphogenesis and patterning of the vertebrate skeleton during embryo development (Krumlauf, 1994; Pearson et al., 2005). The gene HoxA13 in particular is expressed in both the developing autopodia, genital tubercle mesenchyme, and the hindgut and cloacal region, the later resulting in the development of the intestine and urogenital tracts from its terminal end (Dollé et al., 1991a,b; Warot et al., 1997). For our study this gene is an ideal candidate not only because it is involved in the development of traits remarkably modified in snakelike morphologies (e.g. limbs, digestive system and reproductive tract), but also because changes in HoxA13 likely encompass pleiotropy due to its involvement in different developmental processes (for pleiotropic effects of mutations in Hox see Mortlock and Innis, 1997).

The absence of consistent differences between limbed and limbless species in sequence elements of the transcription factor HoxA13 favors the scenario where limb-development motifs in the protein are also committed to other developmental processes. Evidence for this interpretation is also provided by mutations of HoxA13 that are causal for the so-called hand-foot-genital syndrome (Mortlock and Innis, 1997). Such pleiotropic effect of a limb gene on penile structures is explained by the likely serial homology of hind limbs and external genitalia in squamates (Tschopp et al., 2014). Such homology reinforces that changes in limb-related amino acids of the HoxA13 protein are likely to also affect the development of the penis, implying associated fitness costs.

The genetic and evolutionary connections between external genitalia (penis) and limbs may explain the absence of limb-specific variation in the HoxA13amino acid sequence for at least for the two lepidosaurian clades, Serpentes and Amphisbaenia, which have limb-related penises. At this point we do not have a plausible explanation for the evidence for directional selection on the HoxA13 coding sequence in the stem lineage of snakes. It is important to note, though, that the function of Hox genes has undergone substantial reorganization in squamates and snakes in particular (Di-Poï et al., 2010), so there might be other structures in snakes where HoxA13 has acquired novel or modified functions. For example, a characteristic of the Serpentes lineage is the presence cloacal scent glands, a morphological trait evoked previously as a possible candidate for a new function that co-opted HoxA13 in the clade (Kohlsdorf et al., 2008). The hypothesis that HoxA13 may be involved in the development of snake-specific cloacal scent glands has been tested by our group, but no HoxA13 transcripts expressed in these rudiments have been identified using RT-PCR (results not shown). The functional significance of the positive selection detected in the HoxA13 of Serpentes remains therefore under investigation.

The explanation for the lack of a limb-loss signal in the HoxA13amino acid sequence based on the genital-limb connection described by Tschopp et al. (2014) is not applicable to caecilians. These animals do universally have a male copulatory organ, the phalloidium, but this structure is an inverted cloaca and not a body appendage (Gower and Wilkinson, 2002). Given that there are no obvious limb-related appendages in caecilians, one could expect a signal of limb loss in these animals. In fact, there is a substitution from isoleucine (I) to a methionine (M) at position 6 and a deletion of three amino acids (two alanines and a glutamine- AAQ) at positions 76 to 78 of the alignment that are specific to caecilians. However, it is hard to dissect functional significance from phylogenetic signal in these patterns because our dataset lacks additional snakelike and penis-less amphibians other than caecilians, a morphology represented by limbless urodeles.

In summary, we conclude that there is no evidence for limb-specific/exclusive sequence motifs in the HoxA13 amino acid sequence coded for by exon 1, at least in squamates, so that all sequence elements of this part of the protein that are necessary for limb development seem also committed to other developmental processes. We note though, that the C-terminal tail that is coded for by exon 2 is not covered by this study and, thus, we cannot exclude the presence of limb-specific motifs in this part of the HoxA13 molecule.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge FAPESP for PhD fellowships awarded to MBG (2010/00447-7) and SRM (2012/13165-5), and research grants awarded to TK (FAPESP 2011/18868-1, and SISBIOTA FAPESP 2010/52316-3 with CNPq 563232/2010-2) and GPW (NSF#1353691, JTF#54860). We also thank CAPES for a PhD fellowship awarded to MES and a post-doctoral fellowship to MFN. Finally, we acknowledge curators from the collections listed in Supplementary Table 1 for donation of tissue samples used to sequence HoxA13 in the present study.

Supplementary Material.

List of species used in the bioinformatic analyses.

Results from HyPhy analyses in the Data-monkey server.

The following online material is available for this article:

Table S1- List of species used in the bioinformatic analyses.

Figure S1 - Results from HyPhy analyses in the Data-monkey server.

This material is available as part of the online article from http://www.scielo.br/gmb.

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Igor Schneider

References

- Bamshad M, Wooding SP. Signatures of natural selection in the human genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:99–111. doi: 10.1038/nrg999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA. Interacting evolutionary constraints in pelvic reduction of threespine sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus (Pisces, Gasterosteidae) Biol J Linn Soc. 1987;31:347–382. [Google Scholar]

- Brayer KJ, Lynch VJ, Wagner GP. Evolution of a derived protein-protein interaction between HoxA11 and Foxo1a in mammals caused by changes in intramolecular regulation. Proc Natl Acad SciUSA. 2011;108:E414–E420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100990108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakefield PM. Evo-devo and constraints on selection. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakefield PM. Evo-devo and accounting for Darwin’s endless forms. Phil Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2011;366:2069–2075. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn M, Tickle C. Developmental basis of limblessness and axial patterning in snakes. Nature. 1999;399:474–479. doi: 10.1038/20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow KD, Amemiya CT, Roth J, Wagner GP. Hypermutability of HoxA13a and functional divergence from its paralog are associated with the origin of a novel developmental feature in zebrafish and related taxa (cypriniformes) Evolution. 2009;63:1574–1592. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delport W, Poon AFY, Frost SDW, Kosakovsky Pond SL. Datamonkey 2010: A suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2455–2457. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di-Poï N, Montoya-Burgos JI, Miller H, Pourquié O, Milinkovitch MC, Duboule D. Changes in Hox genes’ structure and function during the evolution of the squamate body plan. Nature. 2010;464:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature08789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollé P, Izpisua-Belmonte JC, Brown JM, Tickle C, Duboule D. HOX-4 genes and the morphogenesis of mammalian genitalia. Genes Dev. 1991a;5:1767–1776. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.10.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollé P, Izpisúa-Belmonte JC, Boncinelli E, Duboule D. The Hox-4.8 gene is localized at the 5′ extremity of the Hox-4 complex and is expressed in the most posterior parts of the body during development. Mech Dev. 1991b;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(91)90067-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromental-Ramain C, Warot X, Messadecq N, LeMeur M, Dollé P, Chambon P. Hoxa-13 and Hoxd-13 play a crucial role in the patterning of the limb autopod. Development. 1996;122:2997–3011. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galant R, Carroll SB. Evolution of a transcriptional repression domain in an insect Hox protein. Nature. 2002;415:910–913. doi: 10.1038/nature717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans C. Tetrapod limblessness: Evolution and functional corollaries. Am Zool. 1975;15:455–467. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman FR, Bacchelli C, Brady AF, Brueton LA, Fryns JP, Mortlock DP, Scambler PJ. Novel HOXA13 mutations and the phenotypic spectrum of Hand-Foot-Genital Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:197–202. doi: 10.1086/302961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gower DJ, Wilkinson M. Phallus morphology in caecilians (Amphibia, Gymnophiona) and its systematic utility. Bull Nat Hist Mus Zool. 2002;68:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Graur D, Li WH. Fundamentals of Molecular Evolution. 2nd edition. Sinauer Associates Inc; Sunderland: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hall BK. Evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-Devo): Past, present, and future. Evolution: Educ Outreach. 2012;2:184–193. [Google Scholar]

- Head JJ, Polly PD. Evolution of the snake body form reveals homoplasy in amniote Hox gene function. Nature. 2015;520:86–89. doi: 10.1038/nature14042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh-Li HM, Witte DP, Weinstein M, Branford W, Li H, Small K, Potter SS. Hoxa 11 structure, extensive anti-sense transcription, and function in male and female fertility. Development. 1995;121:1373–1385. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis JW, Goodman FR, Bacchelli C, Williams TM, Mortlock DP, Sateesh P, Guttmacher AE. A HOXA13 allele with a missense mutation in the homeobox and a dinucleotide deletion in the promoter underlies Guttmacher syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2002;19:573–574. doi: 10.1002/humu.9036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knosp WM, Scott V, Bächinger HP, Stadler HS. HOXA13 regulates the expression of bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 7 to control distal limb morphogenesis. Development. 2004;131:4581–4592. doi: 10.1242/dev.01327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knosp WM, Saneyoshi C, Shou S, Bächinger HP, Stadler HS. Elucidation, quantitative refinement, and in vivo utilization of the HOXA13 DNA binding site. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6843–6853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi A, Behringer RR. Developmental genetics of the female reproductive tract in mammals. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:969–980. doi: 10.1038/nrg1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlsdorf T, Cummings MP, Lynch VJ, Stopper GF, Takahashi K, Wagner GP. A molecular footprint of limb loss: Sequence variation of the autopodial identity gene Hoxa-13. J Mol Evol. 2008;67:581–593. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumlauf R. Hox genes in vertebrate development. Cell. 1994;78:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande R. Evolutionary mechanism of limb loss in tetrapods. Evolution. 1978;32:73–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1978.tb01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch VJ, Wagner GP. Resurrecting the role of transcription factor change in developmental evolution. Evolution. 2008;62:2131–2154. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch VJ, Roth JJ, Takahashi K, Dunn CW, Nonaka DF, Stopper GF, Wagner GP. Adaptive evolution of HoxA-11 and HoxA-13 at the origin of the uterus in mammals. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;271:2201–2207. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield JH. Cis-regulatory change associated with snake body plan evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sc USA. 2013;110:10473–10474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307778110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortlock DP, Innis JW. Mutation of HOXA13 in hand-foot-genital syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;15:179–180. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortlock DP, Post LC, Innis JW. The molecular basis of hypodactyly (Hd): A deletion in Hoxa13 leads to arrest of digital arch formation. Nat Genet. 1996;13:284–289. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortlock DP, Sateesh P, Innis JW. Evolution of N-terminal sequences of the vertebrate Hoxa-13 protein. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:151–158. doi: 10.1007/s003350010029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murrell B, Wertheim JO, Moola S, Weighill T, Scheffler K, Kosakovosky Pond SL. Detecting diversifying sites subject to episodic diversifying selection. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Olea G, Wake DB. Extreme morphological and ecological homoplasy in tropical salamanders. Proc Natl Acad ScUSA. 2001;98:7888–7891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131203598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlicev M, Wagner GP. A model of developmental evolution: Selection, pleiotropy and compensation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2012;27:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlicev M, Widder S. Wiring for independence: Positive feedback motifs facilitate individuation of traits and development and evolution. J Exp Zool Mol Dev Evol. 2015;324B:104–113. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.22612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JC, Lemons D, McGinnis W. Modulating Hox gene functions during animal body patterning. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:893–904. doi: 10.1038/nrg1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez WD, Weller CR, Shou S, Stadler HS. Survival of hoxa13 homozygous mutants reveals a novel role in digit patterning and appendicular skeletal development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:446–457. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyron AR, Wiens JJ. A large-scale phylogeny of Amphibia including over 2800 species, and a revised classification of extant frogs, salamanders, and caecilians. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2011;61:543–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyron RA, Burbrink FT, Wiens JJ. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13:e93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff RA. Evo-devo: The evolution of a new discipline. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:74–79. doi: 10.1038/35049594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reno PL, McLean CY, Hines JE, Capellini TD, Bejerano G, Kingsley DM. A penile spine/vibrissa enhancer sequence is missing in modern and extinct humans but Is retained in multiple primates with penile spines and sensory vibrissae. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronshaugen M, McGinnis N, McGinnis W. Hox protein mutation and macroevolution of the insect body plan. Nature. 2002;415:914–917. doi: 10.1038/nature716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Mauro D, Gower DJ, Müller H, Loader SP, Zardoya R, Nussbaum RA, Wilkinson M. Life-history evolution and mitogenomic phylogeny of caecilian amphibians. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2014;73:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou S, Carlson HL, Perez WD, Stadler HS. HOXA13 regulates Aldh1a2 expression in the autopod to facilitate interdigital programmed cell death. Dev Dyn. 2013;242:687–698. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivanantharajah L, Percival-Smith A. Differential pleiotropy and HOX functional organization. Dev Biol. 2015;398:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler HS, Higgins KM, Capecchi MR. Loss of Eph-receptor expression correlates with loss of cell adhesion and chondrogenic capacity in Hoxa13 mutant limbs. Development. 2001;128:4177–4188. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern DL. Perspective: Evolutionary developmental biology and the problem of variation. Evolution. 2000;54:1079–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor HS, Heuvel GV, Igarashi P. A conserved Hox axis in the mouse and human female reproductive system: Late establishment and persistent adult expression of the Hoxa cluster genes. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:1338–1345. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.6.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschopp P, Sherratt E, Sanger TJ, Groner AC, Aspiras AC, Hu JK, Tabin CJ. A relative shift in cloacal location repositions external genitalia in amniote evolution. Nature. 2014;516:391–394. doi: 10.1038/nature13819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warot X, Fromental-Ramain C, Fraulob V, Chambon P, Dollé P. Gene dosage-dependent effects of the Hoxa-13 and Hoxd-13 mutations on morphogenesis of the terminal parts of the digestive and urogenital tracts. Development. 1997;124:4781–479. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.23.4781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens JJ, Brandley MC, Reeder TW. Why does a trait evolve multiple times within a clade? Repeated evolution of snakelike body form in squamate reptiles. Evolution. 2006;60:93–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltering JM. From lizard to snake; behind the evolution of an extreme body plan. Curr Genomics. 2012;13:e289. doi: 10.2174/138920212800793302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltering JM, Vonk FJ, Müller H, Bardine N, Tuduce IL, de Bakker MA, Richardson MK. Axial patterning in snakes and caecilians: Evidence for an alternative interpretation of the Hox code. Dev Biol. 2009;332:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray GA. The evolutionary significance of cis-regulatory mutations. Nature Rev Genet. 2007;8:206–216. doi: 10.1038/nrg2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Wong WS, Nielsen R. Bayes empirical Bayes inference of amino acid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1107–1118. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Nielsen R, Yang Z. Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:2472–2479. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of species used in the bioinformatic analyses.

Results from HyPhy analyses in the Data-monkey server.