Abstract

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) is the fifth most produced oil crop worldwide. Besides lack of water, fungal diseases are the most limiting factors for the crop. Several species of Arachis are resistant to certain pests and diseases. This study aimed to successfully cross the A-genome with B-K-A genome wild species previously selected for fungal disease resistance, but that are still untested. We also aimed to polyplodize the amphihaploid chromosomes; cross the synthetic amphidiploids and A. hypogaea to introgress disease resistance genes into the cultivated peanut; and analyze pollen viability and morphological descriptors for all progenies and their parents. We selected 12 A-genome accessions as male parents and three B-genome species, one K-genome species, and one A-genome species as female parents. Of the 26 distinct cross combinations, 13 different interspecific AB-genome and three AA-genome hybrids were obtained. These sterile hybrids were polyploidized and five combinations produced tetraploid flowers. Next, 16 combinations were crossed between A. hypogaea and the synthetic amphidiploids, resulting in 11 different hybrid combinations. Our results confirm that it is possible to introgress resistance genes from wild species into the peanut using artificial hybridization, and that more species than previously reported can be used, thus enhancing the genetic variability in peanut genetic improvement programs.

Keywords: peanut, interspecific hybrids, polyploidization, colchicine, pollen viability

Introduction

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) is the fifth most produced oil crop worldwide and is also an important food crop (USDA, 2013a). Peanut production worldwide is reported to be greater than 36 million tons per year (USDA, 2013b). In Brazil, approximately 85,000 hectares are farmed in peanuts, and 230,000 tons were produced in 2011 (Martins, 2011). The main problem in peanut production comprises the following fungal diseases: late and early leaf spot, rust, web blotch, and scab.

Species of the genus Arachis have been intensively studied, and several wild species are more resistant to diseases compared to A. hypogaea (Stalker and Moss, 1987; Fávero et al., 2009). The genus Arachis includes 80 species, with 31 belonging to the section Arachis (Krapovickas and Gregory, 1994; Valls and Simpson, 2005). Many species of this section can be crossed with A. hypogaea using artificial hybridization and polyploidization techniques. Introgressing wild genes into the cultivated peanut not only improves important traits, i.e., disease resistances, but also enlarges the peanuts genetic basis. The section Arachis comprises annual and perennial diploid species with varying degrees of similarity to the two tetraploid genomes, A. hypogaea and A. monticola Krapov. & Rigoni (Krapovickas and Gregory, 1994). The perennial species of section Arachis have 20 chromosomes, are closely associated with the A-genome, and are genetically very closely related. Thus, they cross with each other more easily than with non-A-genome species (Stalker, 1989; Stalker et al., 1991), and can be identified by the presence of the small A chromosome pair (Husted, 1933, 1936). Species of section Arachis that lack this small chromosome pair are more heterogeneous, comprising a group with 2n = 18 chromosomes (Lavia, 1998; Peñaloza and Valls, 2005), another with six subtelocentric chromosome pairs (Fernández and Krapovickas, 1994), and a third group with 20 metacentric or submetacentric chromosomes. This third group includes A. ipaënsis (Fernández and Krapovickas, 1994), the most probable donor of the peanut B-genome, and other species with distinct degrees of affinity to A. magna, A. gregoryi, and A. valida (Robledo and Seijo, 2010).

Three pathways were described (Simpson, 1991; Simpson et al., 2001) to introgress genes from wild species into A. hypogaea: (1) hexaploid, (2) tetraploid x tetraploid, and (3) diploid x diploid/tetraploid. This last introgression pathway exhibited the most promising results in other studies (Burow et al., 2001; Fávero et al., 2006), and also in this current study. A variation of this technique was conducted by Simpson and Starr (2001), who first crossed two wild diploids with the A-genome and then crossed them with a B-genome diploid, following the aforementioned steps.

On average, hybrids between A. hypogaea and amphidiploids (AABB) have a higher bivalent association than hybrids between A. hypogaeaand single autopolyploids (AAAA), which represents an additional pathway that produces the most normal meiosis, and consequently, higher pollen fertility (Singh, 1986). This author observed differences between hybrids [(A. batizocoi Krapov. & W. C. Gregory x A. diogoi Hoehne) x A. hypogaea] and their reciprocal crosses, showing that cytoplasmatic differences occur and that A. hypogaea should be used as the female parent due to the resulting pollen viability and seed production. Furthermore, the hybridization between two synthetic autotetraploids derived from two wild species following a cross between A. hypogaea may increase the proportion of desirable traits (Singh et al., 1991). This occurs due to the homeologous pairing observed, which results in genetic changes for both A. hypogaea genomes.

Simpson and Starr (2001) first reported a peanut cultivar resistant to root-knot nematode introgressed from Arachis wild species, named cv. COAN.Molecular markers (DNA probes) were used to study chromatin introgression of this synthetic amphiploid, resistant to the nematode Meloidogyne arenaria, into cultivated peanut (Burow et al., 2001). In the variant pathway crosses {A. hypogaea x[A. batizocoi x(A. cardenasii Krapov. & W. C. Gregory x A. diogoi)]}, they found that chromatin from A-genome wild species, A. cardenasiiand A. diogoi, formed chromosomal mosaicism, indicating recombination events between the species. In the tetraploid progeny, chromosome recombination was similar to that observed in A. hypogaea, where recombination usually occurred between chromosomes from the same genome (A or B). Enhanced yield in lines were obtained from crosses between A. cardenasii and A. hypogaea, showing that wild species of Arachis have useful genes that improve quantitative traits in the cultivated peanut; one recurrent selection cycle was enough to increase yield by approximately 6% (Guok et al., 1986). These authors found that other traits decreased, such as fruit length (1 cm fruit-1/cycle) and extra-large seed count (2.2% per cycle).

This study aimed to successfully cross A-genome with B-K-A genome wild species previously selected for fungal disease resistance, but that are still untested. We also aimed to polyploidize the amphihaploid chromosomes; cross the synthetic amphidiploids and A. hypogaea to introgress the disease resistance genes into the cultivated peanut; and analyze pollen viability and morphological descriptors for all of the progenies and their parents.

Material and Methods

Plant material

The following wild species were used in this study: A. batizocoiKrapov. & W. C. Gregory, collector code K 9484 (BRA-013315); A. cardenasii Krapov. & W. C. Gregory, GKP 10017 (BRA-013404); A. diogoi Hoehne, GK 10602 (BRA-013391); A. duranensis Krapov. & W. C. Gregory, VNvEv 14167 (BRA-036200); A. gregoryi C.E.Simpson, Krapov. & Valls VSGr 6389 (BRA-012696); A. helodes Martius ex Krapov. & Rigoni, VSGr 6325 (BRA-012505); A. hoehnei Krapov. & W. C. Gregory, KG 30006 (BRA-036226); A. ipaënsis Krapov. & W. C. Gregory, KGPScS 30076 (BRA-036234); A. kempff-mercadoi Krapov., W. C. Gregory & C. E. Simpson V 13250 (BRA-030643); A. kuhlmanniiKrapov. & W. C. Gregory VPoJSv 10506 (BRA-024953); A. kuhlmannii VSPmSv 13721 (BRA-033723); A. linearifolia Valls, Krapov. & C. E. Simpson VPoBi 9401 (BRA-022608); A. magna Krapov., W. C. Gregory & C. E. Simpson VSPmSv 13751 (BRA-033812); A. magna KGSSc 30097 (BRA-036871); A. simpsonii Krapov. & W. C. Gregory VSPmSv 13710 (BRA-033685); A. stenosperma Krapov. & W. C. Gregory VGaRoSv 12488 (BRA-030651); A. stenosperma Lm 3 (BRA-036005); and A. villosa Benth, VGoMrOv 12812 (BRA-030813). The genotypes of A. hypogaea subsp. fastigiata var. fastigiata were as follows: cv. BR1 (BRA-033383) and cv. IAC-Tatu-ST (BRA-011606). The genotypes of A. hypogaea subsp. hypogaea var. hypogaea were as follows: cv. IAC-Runner 886 (BRA-037389) and cv. IAC Caiapó (BRA-037371).

Seeds from these wild species were provided by the ArachisGermplasm Bank of Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology, Brasília, Brazil, and cultivated peanut seeds were provided by the Agronomic Institute (Instituto Agronomico), Campinas, Brazil.

Crosses

The species and their cross combinations were chosen based on evaluating the following: resistance to Cercospora arachidicola Hori, Cercosporidium personatum (Benk & Curt.) Deighton, and Puccinia arachidis Speg (Fávero et al., 2009), genetic diversity, life cycle, and seed production. We also preferred using Brazilian accessions and those in previous evolutionary studies on cultivated peanut (Kochert et al., 1991; Fernández and Krapovickas, 1994; Krapovickas and Gregory, 1994; Kochert et al., 1996; Raina and Mukai, 1999a,b).

Diploid male parents (12 A-genome accessions) were crossed between diploid female parents (four B-genome accessions, one K-genome accession, and one A-genome accession), totaling 25 different combinations (Table 1). B-and K-genome accessions were used as female parents because they are annual and more prolific seed producers than most A-genome accessions used in this study. Arachis hoehnei was included among the female parents because previous studies conducted with this species classified it as B-genome sensu lato (Krapovickas and Gregory, 1994; Holbrook and Stalker, 2003), however it is actually an A-genome species (Tallury et al., 2005; Cunha et al., 2008; Friend et al., 2010; Ren et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011). Hybridization involved emasculation of the female parent’s buds in the early evening and then pollination early the next morning. After hybrid polyploidization, according to colchicine treatment described below, 16 different combinations were crossed between four female parents (A. hypogaea cultivars) and four male parents (synthetic amphidiploids – [A. hoehnei x A. helodes]4x; [A. hoehnei x A. cardenasii]4x; [A. gregoryix A. linearifolia]4x) ; [A. gregoryi x A. villosa]4x.

Table 1. Genome assignment of the parents, Number of pollinations, number of hybrids, success rate, and pollen viability in diploid (PV 2x %) and tetraploid (PV 4x %) conditions for each combination of accessions of diploid species of Arachis analyzed.

| Crosses (species and germplasm accessions) | Genome assignment | Number of pollinations | Number of hybrids | Success rate (%) | PV 2x (%) | PV 4x (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. batizocoi 9484 x A. cardenasii 10017 | KK x AA | 39 | 12 | 30.77 | 0.13 f | |

| A. batizocoi 9484 x A. kempff-mercadoi 13250 | KK x AA | 75 | 21 | 28.00 | 0.40 f | |

| A. batizocoi 9484 x A. helodes 6325 | KK x AA | 35 | 8 | 22.86 | 0.79 f | |

| A. gregoryi 6389 x A. duranensis 14167 | BB x AA | 9 | 2 | 22.22 | 4.25 ef | |

| A. batizocoi 9484 x A. duranensis 14167 | KK x AA | 19 | 4 | 21.05 | 0.38 f | |

| A. ipaënsis 30076 x A. villosa 12812 | BB x AA | 88 | 17 | 19.32 | 0.84 f | |

| A. magna 13751 x A. stenosperma 3 | BB x AA | 61 | 6 | 9.84 | 2.86 f | |

| A. gregoryi 6389 x A. linearifolia 9401 | BB x AA | 26 | 2 | 7.69 | 22.99 a | 73.78 |

| A. magna 13751 x A. linearifolia 9401 | BB x AA | 70 | 3 | 4.29 | - | |

| A. magna 13751 x A. cardenasii 10017 | BB x AA | 54 | 2 | 3.70 | 4.76 ef | |

| A. gregoryi 6389 x A. stenosperma 12488 | BB x AA | 228 | 3 | 1.32 | 4.90 ef | |

| A. hoehnei 30006 x A. helodes 6325 | AA x AA | 261 | 1 | 0.38 | 18.97 b | 96.57 |

| A. gregoryi 6389 x A. villosa 12812 | BB x AA | 218 | 2 | 0.92 | 7.68 de | 49.25 |

| A. hoehnei 30006 x A. simpsonii 13710 | AA x AA | 227 | 1 | 0.44 | 16.25 bc | 76.60 |

| A. gregoryi 6389 x A. kuhlmannii 13721 | BB x AA | 256 | 1 | 0.39 | 12.26 cd | |

| A. hoehnei 30006 x A. cardenasii 10017 | AA x AA | 260 | 1 | 0.38 | 24.36 a | 82.17 |

| A. magna 30097 x A. simpsonii 13710 | BB x AA | 251 | 0 | 0.00 | - | |

| A. magna 30097 x A. kuhlmannii 10506 | BB x AA | 291 | 0 | 0.00 | - | |

| A. magna 30097 x A. kempff-mercadoi 13250 | BB x AA | 254 | 0 | 0.00 | - | |

| A. magna 30097 x A. diogoi 10602 | BB x AA | 308 | 0 | 0.00 | - | |

| A. gregoryi 6389 x A. diogoi 10602 | BB x AA | 187 | 0 | 0.00 | - | |

| A. hoehnei 30006 x A. stenosperma 12488 | AA x AA | 262 | 0 | 0.00 | - | |

| A. batizocoi 9484 x A. stenosperma 3 | KK x AA | 87 | 0 | 0.00 | - | |

| A. batizocoi 9484 x A. villosa 12812 | KK x AA | 22 | 0 | 0.00 | - | |

| A. gregoryi 6389 x A. cardenasii 10017 | BB x AA | 21 | 0 | 0.00 | - | |

| Total | 3609 | 86 |

Means not followed by the same letter statistically differ at 5% significance.

Hybrid identification

The hybrids were identified by morphological traits and microsatellite markers. The following morphological markers were used: flower color (if the male parents had yellow flowers, so did its hybrid) and web blotch (Phoma arachidicola) resistance (hybrids from crosses between A. hypogaea and amphidiploids were resistant, but when selfed were susceptible after natural infection under screen-house conditions).

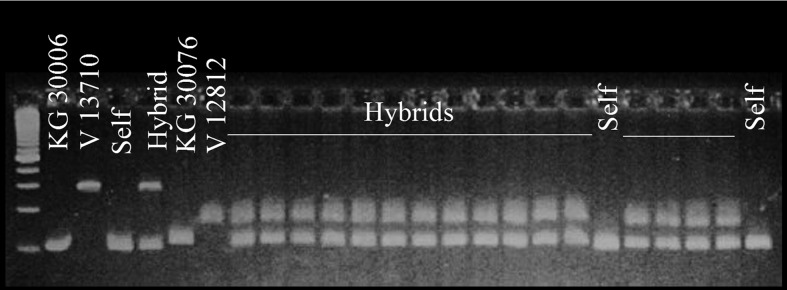

Leaves from each progeny plant were individually collected and DNA was extracted according to the adapted protocol by Murray and Thompson (1980). The DNA was quantified using agarose gels (1.2%) at 80 V for 1 h and diluted to 2.5 ngmL−1 concentration. The PCR reaction for DNA amplification contained the following reagent cocktail: PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, and 50 mM KCl), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM dNTPs, 5 pmol of each primer pair (A1-041, 5′-CGCCACAAGATTAACAAGCACC-3′ and (F) 5′-GCTGGGATCATTGTAGGGAAGG-3′ (R); A1-558, 5′-TGTGACACCATCAATCAAAGGG-3′ (F) and 5′-CAAAACCCAAATCATCACCACC-3′ (R); and LEC-1, (AT) 5′-CAAGCATCAACAACAACGA-3′ (F) and 5′-GTCCGACCACATACAAGAGTT-3′ (R)), 5 U Taq DNA Polymerase, and 10 mg mL−1 BSA (bovine serum albumine), which was mixed separately from DNA; then 2.5 ng mL−1 DNA was added; and Milli-Q sterile water was added to complete the reaction volume to 13 μL. Mineral oil (50 μL) was added to prevent the cocktail from evaporating. The amplification reaction conditions were as follows: denaturation for 5 min at 94 °C; 29 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 56 °C (60 °C for primer pairs A1-041 and A1-558), and 1 min at 72 °C; and a final extension of 7 min at 72 °C. The amplified products were separated by electrophoresis in 4% agarose gel (9 pv−1), using TBE buffer (0.09 of Tris; 0.09 M boric acid, and 2 mM EDTA), pH 8.0, at constant 90 V cm−1. The gels were stained with 10 mL ethidium bromide (10 mg mL−1) diluted in 100 mL TBE and visualized under ultraviolet light (GELDOC 2000, BIORAD). Figure 1 presents PCR amplifications using the LEC primer pair for two hybrid combinations between A-genome wild species (A. hoehnei - KG 30006 and A. simpsonii V 13710) and A- and B-genome wild species (A. ipaënsis KGBPScS 30076 and A. villosa V 12812), and their progeny.

Figure 1. Combinations between Arachis hoehnei and A. simpsonii and A. ipaënsis and A. villosa and their progeny. Agarose gel, using LEC primer.

The morphological traits were evaluated at approximately 210 days after hybrid germination, with adaptations based on the descriptors used for wild species of Arachis (IBPGR, 1990). Descriptors for the V 9401 (A. linearifolia) and V 13721 (A. kuhlmannii) accessions were not evaluated because the plants died at the onset of morphological characterization.

Morphological characterization

The hybrids were morphologically characterized at the Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology Laboratory. The following 27 traits were evaluated: basal and distal leaflet lengths and widths, petiole and petiolule lengths, lengths of the free and adnate portions of the stipules, located on the main axis and lateral branches; width of stipules on the lateral branches; anthocyanin presence on the branches and petiole; standard length, wing length, lower lip length, and hypanthium length of the flowers; and presence of bristles and trichomes on the petiole and leaflet edge. Five leaves were measured per plant, one on the main axis and the other four on the lateral branches, always considering the first expanded leaf and counting from the branch apex.

The data were analyzed using Pearson correlation and principal component analysis (PCA). We used the SAS® software, v 8.2, (PROC COMP function) and constructed 2D graphs based on the values for PC1, PC2 of each trait multiplied by the mean values of each trait from each genotype in Windows Microsoft Excel. The diploid and tetraploid structures were measured and t-test was used for mean comparisons. Based on the PC1 and PC2 values multiplied by the mean values for each trait from each genotype, a bi-dimensional figure was created that corresponds to the genetic diversity of the hybrids and their respective parents.

Plant height was measured along the main axis. The following traits were evaluated on the lateral branch: longest lateral branch length; basal and distal leaflet lengths and widths; internode lengths, (1), (2), and (3); petiole and petiolule lengths; lengths and widths of the free and adnate portions of the stipules; trichomes on the center, edge, and midvein of abaxial and adaxial leaflets, petiole, petiolule, and stipules (center and edge of free and adnate portions); anthocyanin presence on the stipules; and presence of bristles on the leaflet edge, petiole, petiolule, and free and adnate portions of the stipules.

In the amphihaploid and amphidiploid plants, we observed nine descriptors for the main axis, nine for lateral branches, and seven descriptors for flower structures. The amphihaploid plant from A. hoehnei x A. cardenasii cross was not evaluated because it was in too poor condition to compare with the amphidiploid plants.

Colchicine treatment

Ten 20-cm-long cuttings were taken by genotype and placed in bioassay tubes (growing tip down) containing 0.2% colchicine solution (solution approximately 10 cm high). The tubes were sealed with PVC plastic and kept under controlled conditions under fluorescent light at between 28 and 30 °C for 8–12 h. The cuttings were washed under running water for approximately 20 min and planted with rooting hormone in plastic cups containing Plantmax vegetable substrate. The cups were placed in plastic trays and wrapped in a transparent plastic bag to maintain high moisture content. After approximately 20 days, the rooted cuttings were transferred to pots.

The polyploid cuttings were identified by chromosome counts from the adventitious root tips according to Fávero et al. (2004).

Pollen viability evaluation

Eight flowers from each hybrid combination, at the diploid and tetraploid levels, were used to evaluate pollen viability. Each flower was opened and the pollen was placed onto a slide and stained using one drop of 2% acetocarmine.

Stomata characterization

Four newly expanded leaflets from each hybrid combination were cut and scraped until just the abaxial epidermal peel remained. The leaflet tissues were observed on slides under an Axioskop photomicroscope. The stomata were counted by obtaining the mean from five areas under the microscope (at 20x magnification), and mean stomatal size was obtained by measuring 100 stomata using an ocular micrometric scale. The data were subjected to analysis of variance and t-test (p < 0.05) to compare each hybrid combination and means from the amphihaploid and amphidiploid individuals.

Results and Discussion

Crossability between wild species

We obtained between zero and 21 seeds from each diploid cross combination (Table 1). This variation was most likely due to the inherent difficulty in obtaining hybrids from crosses between species with different genomes. Some seeds remained ungerminated, such as those from crosses involving the A. magna accession (KGSSc 30097), and a few seedlings died at the earlier experimental stages. One seed with above-average dormancy was produced, but even treatment with Ethrel solution was unable to break the dormancy.

The microsatellite markers were highly efficient in detecting hybrid individuals (Figure 1). We were able to successfully determine the status of the progeny, whether hybrids or not.

The number of pollinations differed among the hybrid combinations because the number of flowers produced by the female and male parents varied (Table 1). Of the 3,609 pollinations, 86 hybrid plants were obtained. The mean pollination success rate was 4.99%. Of the 25 different hybrid combinations, 16 resulted in hybrid plants, resulting in a 64% efficiency rate.

Based on our results, the crosses can be divided into three large groups. The first group comprises those with the highest success rates, i.e., highest seed count obtained (up to 19.32%). These results confirm that A. batizocoi, often used as a bridge-species for introgressing genes from wild species into the cultivated peanut (Simpson, 1997), is very efficient in interspecific crosses. Very similar results were obtained for the hybridization between A. batizocoi x A. kempff-mercadoi (Tallury et al., 2005). These authors stated that after 34 pollinations, their hybrid combination resulted in a 21% success rate, seven hybrid plants, and 1% pollen viability in hybrids. Arachis gregoryi is morphologically and cytogenetically very similar to A. magna and A. ipaënsis (Robledo and Seijo, 2010). The latter, together with A. duranensis (Kochert et al., 1991; Krapovickas and Gregory, 1994), are the main candidates as parents for the cultivated peanut (Seijo et al., 2004; Fávero et al., 2006).

The second group had success rates ranging between 0.38% and 9.84%. Because A. hoehnei is an A-genome species that was misclassified as B-genome for many years, such hybrids were only used if they were able to cross with B-genome species, followed by polyploidization and hybridization with A. hypogaea.

The third group comprises the following crosses that failed to produce hybrids. The A. magna accession (KGSSc 30097), corresponding to the population that provided the type specimen, failed to produce a hybrid when crossed between any of the A-genome species chosen as male parents. Thus, although A. hoehnei has a genome formula of AA, it remains genetically distant from the other A-genome species that it was crossed with.

Many molecular-based researchers have found that A-genome species remained in different subgroups than B-genome species sensu lato (Cunha et al., 2008; Friend et al., 2010: Wang et al., 2011). This indicates that, although A-genome species are included in section Arachis, A-genome and B-genome species are genetically distant enough to explain the low success rate and fertility of the interspecific hybrids obtained in our study.

Difficulties in obtaining successful hybrids from the crosses K-genome A. batizocoi (K 9484) x A-genome A. kuhlmannii (KG 30008) and K-genome A. batizocoi (K 9484) x A-genome A. cardenasii (GKP 10017) were reported (Stalker et al., 1991), where one died and the other produced stunted plants, respectively. However, when crossing A. batizocoi with other species, such as A-genome A. diogoi (KG 30001), they obtained 35 hybrid plants. In our study, we obtained hybrid plants with normal growth from crossing A. batizocoi (K 9484) and A. cardenasii (GKP 10017), contrasting with results reported by Stalker et al. (1991).

Morphological traits of diploid hybrids and parents

The eigenvalues for the morphological data showed that the first three components combined explained 85.68% (PC1 = 0.46, PC2 = 0.71, PC3 = 0.86) of the total variation in the morphological traits).

Of the 62 traits evaluated, 15 were considered important for discriminating between accessions and hybrids. The descriptors were selected by behavior and importance according to the first principle component (PC1). Most of the descriptors chosen that best explained the variation in PC1 were also listed as key descriptors in the second (PC2) and third components (PC3). The descriptors selected for the group analysis and codes used for identification were as follows (in order of importance): longest lateral branch length (cmRL); internode length from lateral branch (2) (dee2RL); internode length from lateral branch (3) (dee3RL); internode length from lateral branch (1) (dee1RL); petiole length on the main axis (cpEC); basal leaflet length on the main axis (cf1EC); distal leaflet length on the main axis (cf2EC); basal leaflet width on the main axis (lf1EC); basal leaflet width on the lateral branch (lf1RL); plant height (apEC); distal leaflet width on the main axis (lf2EC); basal leaflet length on the lateral branch (cf1RL); distal leaflet width on the lateral branch (lf2RL); petiole length on the lateral branch (cpRL); and distal leaflet length on the lateral branch (cf2RL).

Morphological variation was studied in the progeny produced from crosses between A. hypogaea and A. cardenasii, triploids that were polyploidized and selfed many times until obtaining tetraploid and fertile conditions (Stalker et al., 1979). Based on PCA, the first two axes (PC1 and PC2) combined explained 63.4% of the total variation. Most of the hybrids of the F6C5 generation appeared to be most similar to A. hypogaea. However, several plants were similar to A. cardenasii. These morphological differences observed among plants can be explained by genes being introgressed into the genome of A. hypogaea or via chromosomal substitution. The fruit length and seed width traits seemed to be most important in distinguishing between wild and cultivated species. The seed length:seed width ratio separated three out of four cultivated species varieties. In characterizing infection by Cercospora arachidicola, only a few hybrid plants could be considered highly resistant.

There is a high positive correlation (ranging from 0.70 to 0.99) among all of the traits related to leaflet length (proximal and distal on the main axis and lateral branch), leaflet width (proximal and distal on the main axis and lateral branch), and petiole length (on the main axis and lateral branch). These are consistent results because the traits are from the same category, i.e., leaflet shape and size. There were positive correlations (ranging from 0.61 to 0.74) among internode lengths (1, 2, and 3). There were positive correlations (ranging from 0.45 to 0.81) between plant height and internode lengths (1, 2, and 3) on the main axis. There were positive correlations between petiole length on the lateral branch and plant height (0.45) and petiole length on the lateral branch and distance between the second and third stipules on the lateral branch (0.39). The other traits evaluated remained uncorrelated. As these values can be considered reliable, we recommend a more detailed emphasis on the correlated traits in future studies.

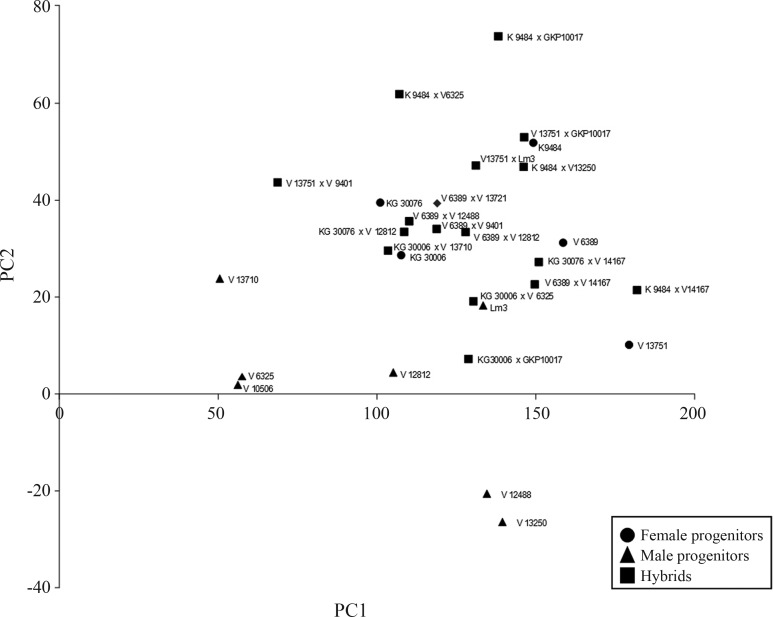

According to Figure 2, each cross type exhibited different behaviors. The male parents are located more to the left of the graph and the female ones to the right. The hybrids A. batizocoi K 9484 x A. helodes V 6325, A. batizocoi K 9484 x A. cardenasii GKP 10017, A. magna V 13751 x A. cardenasii GKP 10017, A. magna V 13751 x A. stenosperma Lm 3, and A. gregoryi V 6389 x A. villosa V 12812 are located above their respective parents on the graph. It means that the results of the main morphological descriptors for hybrids are very different to both parent values. The hybrids A. hoehnei KG 30006 x A. cardenasii GKP10017, A. batizocoi K 9484 x A. kempff-mercadoi V 13250, A. ipaënsisKG 30076 x A. villosa V 12812, A. hoehnei KG 30006 x A. simpsonii V 13710, and A. hoehneiKG 30006 x A. helodes V 6325 are between their two respective parents, but closer to the female ones. Based on the principal components, values of the main morphological descriptors of hybrids were between the values of both parents. The hybrid A. magna V 13751 x A. linearifolia V 9401 is located far from its female parent which means that the results of the main morphological descriptors for hybrids are very different to the female parent values. The hybrids A. gregoryi V 6389 x A. kuhlmannii V 13721, A. gregoryi V 6389 x A. linearifolia V 9401, A. gregoryi V 6389 x A. stenosperma V 12488, and A. gregoryi V 6389 x A. villosa V 12812 are close to each other and to A. gregoryi V 6389. The hybrids resulting from A. duranensis V 14167 as male parent are closer to one another and farther from their respective female parents, except hybrids resulting from A. gregoryi as female parent. As it was not possible to take measurements for the V 14167 accession, we can only infer that it and its hybrid would have been located on the right side of the graph. The hybrids were usually closer to the female parents than the male parents. This means that there may be some cytoplasmic genes capable of influencing the hybrid plants’ phenotype.

Figure 2. PCA of 15 main descriptors for Arachis accession female and male parents and their hybrids.

Colchicine treatment

The cuttings with tetraploid leaves had diploid rooting systems, so we avoided treating the rooted area with colchicine to allow for rooting. Therefore, only the shoots of the cuttings were treated to obtain amphidiploid plants. The colchicine treatment was efficient, although many cuttings died and others were chimeric plants (having both diploid and tetraploid cells). Using detached leaves to obtain root tips is effective for observing cells in mitotic metaphase (Fávero et al., 2004) where several metaphase cells were observed per plant in our study. The hybrid combination between A. ipaënsis KG 30076 and A. duranensis V 14167 exhibits polyploid cells after eight hours of colchicine exposure (Fávero et al., 2006). All of the other hybrid combinations required 12 hours of colchicine exposure to effectively double.

The chimeric plants were capable of producing seeds because some of their flowers were tetraploid (Table 1). It is possible to obtain tetraploid plants from these seeds because they were produced by fusion between diploid gametes. Although chromosome doubling is a research bottleneck, this pathway for introgressing genes into cultivated peanut plants is still the most successful compared to other tested methods (Simpson, 1991).

Pollen viability evaluation in amphihaploids and amphidiploids

Flowers on the diploid hybrids had sterile pollen and the anthers were unable to open. When these anthers are artificially opened, the pollen stays attached. When tetraploid flowers (from interspecific hybrids AABB) are artificially opened, pollen is released the same way as in flowers on normal fertile accessions from the germplasm bank. The diploid and tetraploid plants were distinct according to the stained pollen viability test (Table 1), as follows: the mean stained pollen data for the diploids hybrids ranged from 0.13 to 24.36 and for the tetraploids ranged from 49.25 to 96.57 (Table 1). Mallikarjuna et al.(2011) obtained 17 new amphidiploids and also achieved pollen fertility. Although pollen viability in tetraploid individuals was considered very high, only the amphidiploids A. gregoryi x A. linearifolia and A. ipaënsis x A. duranensis produced up to 30 seeds and the other amphidiploids produced very few seeds.

Morphological characterization in amphihaploids and amphidiploids

There were differences between diploid and tetraploid plants for all of the hybrid combinations, except for A. hoehnei KG 30006 x A. cardenasii GKP 10017. The amphihaploid plant was in poor condition and thus could not be measured and compared with the amphidiploid individuals.

There were differences between the diploid and tetraploid individuals in most of the hybrid combinations for the following morphological descriptors (Table 2): A) distal and basal leaflet widths, petiole and petiolule lengths, and length of the free portion and width of the adnate portion of the stipules, on the main axis; B) basal leaflet length and width of the adnate portion of the stipules, on the lateral branch; and C) standard length, wing length, lower lip length, and hypanthium length of the flowers.

Table 2. Morphological descriptors on the main axis, lateral branch, and flowers and stomata size under diploid (2x) and tetraploid (4x) conditions (in millimeters).

| Descriptors | Ploidy | KG 30006 x V 6325 | KG 30006 x V 13710 | V 6389 x V 9401 | KG 30076 x V 14167 1 | KG 30006 x GKP 10017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main Axis | ||||||

| Distal leaflet length | 2x | 28.88 | 30.39 | 37.27* | 45.59 | - |

| 4x | 28.72 | 48.73 | 65.62* | 51.47 | 45.45 | |

| Basal leaflet length | 2x | 25.14 | 26.8* | 31.4* | 38.53 | - |

| 4x | 26.51 | 43.75* | 57.12* | 46.22 | 39.58 | |

| Distal leaflet width | 2x | 11.66* | 13.7* | 13.57* | 25.74 | - |

| 4x | 16.94* | 19.59* | 23.23* | 29.69 | 23.44 | |

| Basal leaflet width | 2x | 9.88* | 10.45* | 10.58* | 21.76 | - |

| 4x | 13.33* | 15.2* | 19.00* | 23.39 | 19.38 | |

| Petiolule length | 2x | 6.92* | 6.47* | 11.03* | 15.61* | - |

| 4x | 9.21* | 12.12* | 16.48* | 19.16* | 11.64 | |

| Petiole length | 2x | 31.46* | 24.54* | 30.34* | 58.02* | - |

| 4x | 53.53* | 49.14* | 64.4* | 71.73* | 50.28 | |

| Stipules (adnate) length | 2x | 6.78 | 8.71 | 7.36* | 12.34* | - |

| 4x | 6.43 | 12.75 | 10.13* | 14.99* | 10.36 | |

| Stipules (free) length | 2x | 13.87 | 14.24* | 16.14* | 21.35* | - |

| 4x | 14.31 | 25.9* | 35.93* | 30.22* | 23.04 | |

| Stipules (adnate) width | 2x | 2.69* | 1.79* | 2.82* | 3.36* | - |

| 4x | 3.71* | 3.4* | 4.75* | 4.62* | 4.72 | |

| Lateral Branch | ||||||

| Distal leaflet length | 2x | 23.08 | 20.59 | 26.34 | 27.16* | - |

| 4x | 18.43 | 28.28 | 28.67 | 37.64* | 25.24 | |

| Basal leaflet length | 2x | 16.00* | 16.01* | 21.4 | 23.13* | - |

| 4x | 20.66* | 25.55* | 25.12 | 33.22* | 21.8 | |

| Distal leaflet width | 2x | 11.95 | 12.16* | 14.32 | 21.89* | - |

| 4x | 13.84 | 20.01* | 16.11 | 31.17* | 21.37 | |

| Basal leaflet width | 2x | 10.19 | 9.78* | 9.91 | 17.75* | - |

| 4x | 10.47 | 16.71* | 12.32 | 23.25* | 17.27 | |

| Petiole length | 2x | 24.97 | 13.88* | 27.71 | 22.08* | - |

| 4x | 22.23 | 22.88* | 22.69 | 36.88* | 23.21 | |

| Petiolule length | 2x | 6.7 | 3.7 | 9.00 | 11.14* | - |

| 4x | 7.19 | 8.95 | 9.7 | 16.07* | 8.85 | |

| Stipules (adnate) length | 2x | 6.82* | 3.83 | 5.82* | 6.75* | - |

| 4x | 4.82* | 4.16 | 4.94* | 8.37* | 5.24 | |

| Stipules (free) length | 2x | 11.7 | 9.22* | 11.23* | 14.21 | - |

| 4x | 11.23 | 16.69* | 17.89* | 15.98 | 14.62 | |

| Stipules (adnate) width | 2x | 2.59* | 2.92* | 2.93* | 4.01* | - |

| 4x | 3.5* | 4.54* | 4.69* | 5.55* | 4.17 | |

| Flower | ||||||

| standard length | 2x | 1.37* | 0.83* | 1.28* | 1.30 | |

| 4x | 1.50* | 2.40* | 1.75* | 1.45 | ||

| standard width | 2x | 1.68 | 1.27 | 1.44* | 1.71 | |

| 4x | 1.81 | 1.22 | 1.64* | 1.69 | ||

| wing length | 2x | 0.84* | 0.82* | 0.74* | 0.81 | |

| 4x | 0.95* | 1.05* | 0.88* | 0.84 | ||

| wing width | 2x | 0.86* | 0.47* | 0.72 | 0.81 | |

| 4x | 0.95* | 0.65* | 0.70 | 0.84 | ||

| lower lip length | 2x | 0.77* | 0.70* | 0.63* | 0.64* | |

| 4x | 0.90* | 0.88* | 0.90* | 0.82* | ||

| back lip length | 2x | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.57* | 0.61* | |

| 4x | 0.72 | 0.68 | 0.64* | 0.71* | ||

| hypanthium length | 2x | 5.05 | 5.04* | 3.70* | 3.47* | |

| 4x | 4.51 | 5.89* | 4.78* | 4.47* | ||

| No. stomata/area | 2x | 131.65 | 104.65 | 140.35 | 121.05 | 146.9 |

| 4x | 86.1 | 97.25 | 61.95 | 96.45 | 102.65 | |

| Stomata size (μm) | 2x | 8.72 | 9.08 | 9.28 | 8.52 | 9.00 |

| 4x | 11.92 | 11.20 | 12.58 | 10.96 | 12.42 |

Values that differed between treatments, considering cut-off at 5% probability.

Data for flower descriptors of KG 30076 x V 14167 have already been published by Fávero et al. (2006).

The hybrid A. hoehnei KG 30006 x A. simpsonii V 13710 exhibited the most morphological structures with gigantism effects. In roses, chromosome-doubling using oryzalin made some of the morphological traits appear larger, i.e., leaf thickness, induced darker green leaf color, and increased the leaflet width:leaflet length ratio in all diploid-to-tetraploid conversions and one triploid-to-hexaploid conversion; the internodes were longer in amphidiploids than amphihaploids (Kermani et al., 2003).

The sizes of flower structures differed between amphihaploid and amphidiploid individuals for most of the traits and hybrid combinations (Table 2). This corroborates results found in amphidiploids of Dianthus caryophyllus and D. japonicus (Nimura et al., 2006). A plausible explanation for these differences among the hybrid combinations is higher polyploid efficiency with increasing flower size. Flowers on the hybrid A. hoehnei x A. cardenasii were already large under diploid conditions, so perhaps there was no expansion in the mechanism when doubled.

Stomata characterization

Stomata size and count differed between amphihaploid and amphidiploid individuals for all of the hybrid combinations (Table 2). There was an interaction between hybrids and ploidy level. The amphihaploid plants had more and smaller stomata per area compared to amphidiploid plants for all of the combinations by t-test. These results corroborates the data obtained by Singsit and Ozias-Akins (1992) in interspecific hybris of Arachis, A. hypogaea, A. stenosperma, A. batizocoi and A. villosulicarpa. In banana plants (Vandenhout et al., 1995), where more, smaller stomata per area was correlated with low ploidy level, and vice versa. This has been observed as well in watermelon (Sari et al., 1999), black wattle (Beck et al., 2003), and many other species. However, stomata size is not a reliable criterion for characterizing ploidy level in Hemarthria altissima (Tedesco et al., 1999). Thus, stomatal characterization is useful for distinguishing between amphihaploid and amphidiploid plants in Arachis and many other genera.

Hybridizations between synthetic amphidiploids and Arachis hypogaea

After hybridization of 1,814 flowers, 27 different hybrid types were obtained from crosses between A. hypogaea and synthetic amphidiploids, with success rates ranging from 0 to 5.26% (Table 3). The percentage of hybrids obtained compared with pollination count (success rate) varied according to the parents. Hybrids from crosses involving the amphidiploid [A. hoehnei x A. cardenasii]4x exhibited boat-shaped leaves, typical of species A. hoehnei. Trichomes along the leaf edges were also occasionally observed. Hybrids between the Runner types IAC Caiapó and IAC Runner and the amphidiploids [V6389 A. gregoryi x V9401 A. linearifolia]4x expressed traits differently compared to hybrids from crosses between the Spanish types IAC Tatu ST and BR-1 and [V6389 A. gregoryi x V9401 A. linearifolia]4x. Hybrids from crosses using Runner types as parents produced seeds and hybrids from crosses using Spanish types or IAC-Tatu-ST x [KG30006 A. hoehnei xV 6325 A. helodes]4x as parents failed to produce flowers. The hybrids IAC-Caiapó x [KG30006 A. hoehnei x GKP10017 A. cardenasii]4x, IAC-Tatu-ST x [KG30006 A. hoehnei x GKP10017 A. cardenasii]4x, and BR-1 x [V 6389 A. gregoryi x V 12812 A. villosa]4x produced flowers, but no seeds.

Table 3. Crosses between Arachis hypogaea accessions and the synthetic amphidiploids, the number of pollinations achieved, number of hybrid plants obtained, success rate, and number of F2seeds.

| Accessions of A. hypogaea | Accessions | Number of pollinations | Number of hybrid plants | Success rate (%) | Number of F2 seeds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BR 1 | X | [V 6389 x V 12812]4x | 19 | 1 | 5.26 | 0 |

| IAC-Caiapó | X | [V 6389 x V 12812]4x | 22 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 |

| IAC-Runner | X | [V 6389 x V 12812]4x | 27 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 |

| IAC-Tatu-ST | X | [V 6389 x V 12812]4x | 41 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 |

| BR 1 | X | [KG 30006 x GKP 10017]4x | 56 | 1 | 1.79 | 0 |

| IAC-Caiapó | X | [KG 30006 x GKP 10017]4x | 93 | 1 | 1.08 | 0 |

| IAC-Runner | X | [KG 30006 x GKP 10017]4x | 89 | 1 | 1.12 | 0 |

| IAC-Tatu-ST | X | [KG 30006 x GKP 10017]4x | 56 | 1 | 1.79 | 0 |

| IAC-Tatu-ST | X | [V 6389 x V 9401]4x | 231 | 11 | 4.76 | 0 |

| IAC-Caiapó | X | [V 6389 x V 9401]4x | 141 | 1 | 0.71 | 7 |

| IAC-Runner | X | [V 6389 x V 9401]4x | 190 | 2 | 1.05 | 11 |

| BR 1 | X | [V 6389 x V 9401]4x | 160 | 2 | 1.25 | 0 |

| IAC-Tatu-ST | X | [KG 30006 x V 6325]4x | 181 | 2 | 1.11 | 0 |

| IAC-Caiapó | X | [KG 30006 x V 6325]4x | 147 | 4 | 2.72 | 0 |

| IAC-Runner | X | [KG 30006 x V 6325]4x | 210 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 |

| BR 1 | X | [KG 30006 x V 6325]4x | 151 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 |

| Total | 1814 | 27 |

The microsatellite markers allowed us to distinguish between selfed and hybrid individuals within the progenies.

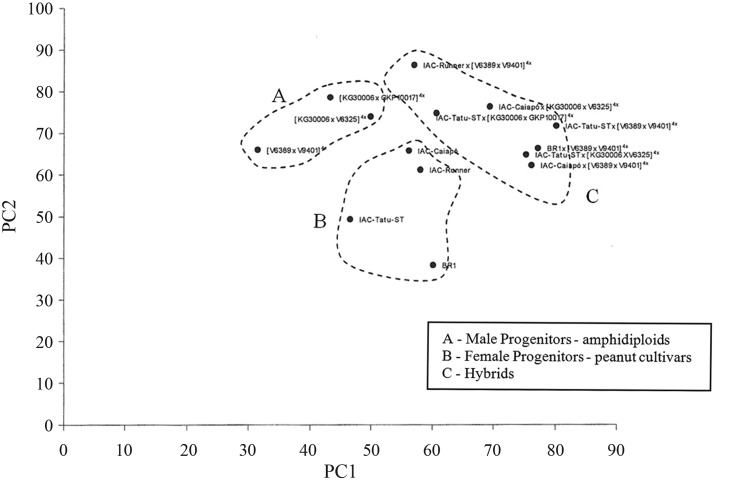

Morphological characterization of F1 hybrids between amphidiploids and A. hypogaea

The mean morphological data on four male parents, three female parents, and seven hybrid combinations were used in principal component analysis (Figure 3). Plants of the other hybrid combinations and one amphidiploid (A. gregoryi x A. villosa) were too poor in condition to be included in the analysis. Of the 23 morphological traits evaluated, 15 were selected as the most important for distinguishing genotypes, i.e., they explained a great part of the total variance observed in PC1 (46.68%). Likewise, in studying Eleusine coracana, 11 out of 29 traits should be discarded from analysis (Hussaini et al., 1997). These discarded traits were mostly vegetative and highly affected by environmental factors, but the reproductive data associated with panicle traits were less affected.

Figure 3. PCA of F1 hybrids obtained by crossing between amphidiploids and A. hypogaea, and their parents.

The 15 traits we propose to be considered for distinguishing phenotypes are: length of the free portion of the stipules, petiole and petiolule lengths, stipule width, distal and basal leaflet lengths, and distal and basal leaflet widths, on the main axis; distal and basal leaflet lengths, petiole and petiolule lengths, length of the free portion of the stipules, and distal and basal leaflet widths, on the lateral branch. These 15 descriptors can be used in future studies on hybrids associated with these traits, thus reducing the number of necessary variables to analyze. Out of these traits we selected in this study, the following 10 descriptors were also used by Fávero et al. (2006): petiole length, distal and basal leaflet lengths, and distal and basal leaflet widths, on the main axis; distal and basal leaflet lengths, petiole length, and distal and basal leaflet widths, on the lateral branch.

We observed that the three principal components explained 91.13% of the total variance among the genotypes. This is satisfactory, since according to Cruz and Regazzi (1997), the three principal components used in studies on genetic diversity explained 80% of the total variance. These results can be compared those of with two other studies (Fávero et al., 2004; and Monçato L (1995) MSc Thesis, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio Mesquita Filho”, Botucatu) also working with wild species and hybrids of Arachis, where 85% and 70% explained the variation, respectively.

The following trends occurred in the correlation matrix (Table 4) using the 15 morphological descriptors that best explained the variation among the genotypes: 1) structures from lateral branches were correlated; 2) the same structures at different locations were correlated, such as length of the free portion of the stipules on the main axis and on the lateral branch, or distal leaflet width on the lateral branch and on the main axis; and 3) some descriptors were correlated, such as basal leaflet length on the main axis and length of the free portion of the stipules on the lateral branch. The correlations between the descriptors were considered significant at 5% probability.

Table 4. Pearson Correlation Coefficient among the 15 main morphological traits selected by PCA.

| ceplEC | cpEC | cpcEC | cfbEC | lfbEC | cfaEC | lfaEC | cpRL | CpcRL | cfbRL | lfbRL | cfaRL | lfaRL | ceplRL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cepaEC | 0.37250 | 0.67749 | 0.63906 | 0.25834 | 0.36064 | 0.32833 | 0.38760 | 0.18725 | 0.18168 | 0.10231 | 0.17339 | 0.06464 | 0.13203 | 0.27303 |

| ceplEC | 0.25490 | 0.19777 | 0.42333 | 0.34562 | 0.59166 | 0.37524 | 0.43510 | 0.45701 | 0.55123 | 0.41775 | 0.54939 | 0.40908 | 0.63894 | |

| cpEC | 0.89217 | 0.32697 | 0.66794 | 0.43380 | 0.69563 | 0.31975 | 0.34412 | 0.21856 | 0.40449 | 0.17780 | 0.37299 | 0.18083 | ||

| cpcEC | 0.20093 | 0.61218 | 0.30156 | 0.58684 | 0.25754 | 0.30851 | 0.14790 | 0.31147 | 0.12319 | 0.29382 | 0.08002 | |||

| cfbEC | −0.03601 | 0.92978 | 0.39393 | 0.22632 | 0.25693 | 0.45542 | 0.30729 | 0.43767 | 0.32124 | 0.37383 | ||||

| lfbEC | 0.19895 | 0.82556 | 0.57778 | 0.66224 | 0.47820 | 0.72009 | 0.46818 | 0.69055 | 0.31061 | |||||

| cfaEC | 0.57200 | 0.37904 | 0.40092 | 0.59825 | 0.46392 | 0.58664 | 0.47001 | 0.50291 | ||||||

| lfaEC | 0.61737 | 0.68435 | 0.61047 | 0.80999 | 0.58790 | 0.78829 | 0.38618 | |||||||

| cpRL | 0.88291 | 0.85104 | 0.84182 | 0.82180 | 0.80457 | 0.64927 | ||||||||

| cpcRL | 0.78751 | 0.85026 | 0.79257 | 0.85033 | 0.59138 | |||||||||

| cfbRL | 0.85815 | 0.98580 | 0.85049 | 0.83243 | ||||||||||

| lfbRL | 0.83725 | 0.98489 | 0.64448 | |||||||||||

| cfaRL | 0.84764 | 0.84738 | ||||||||||||

| lfaRL | 0.65378 |

Trait codes: distal leaflet lengths on main axis (cfaEC); basal leaflet lengths on main axis (cfbEC); distal leaflet widths on main axis (lfaEC); basal leaflet widths on main axis (lfbEC); petiolule length on main axis (cpcEC); petiole length on main axis (cpEC); length of the adnate portions of the stipules on main axis (cepaEC); length of the free portions of the stipules on main axis (ceplEC); distal leaflet lengths on lateral branches (cfaRL); basal leaflet lengths on lateral branches (cfbRL); distal leaflet widths on lateral branches (lfaRL); basal leaflet widths on lateral branches (lfbRL); petiole length on lateral branches (cpRL); petiolule length on lateral branches (cpcRL); length of the free portions of the stipules on lateral branches (ceplRL). Bold data show correlation between traits at 5% probability.

According to Figure 3, there are three distinct groups: 1) hybrid group, 2) female parent group (A. hypogaea), and 3) male parent group (amphidiploids). The main traits that distinguish the genotypes are distal leaflet length, basal leaflet length, and petiole length on the lateral branch.

We found that the structures are largest in the hybrids from crosses between A. hypogaea and the amphidiploids, followed by the A. hypogaea accessions, and finally the synthetic amphidiploids. The larger structures in the triple interspecific hybrids may be explained by the heterosis effect.

Our results confirm that it is possible to introgress genes from wild species into the cultivated peanut using artificial hybridization, and that two more species than previously reported can be used. Maybe the utilization of in vitro techniques to rescue the embryos may increase the number of hybrid combinations. It is thus possible to apply this novel approach using 15 descriptors to enhance the genetic variability in peanut genetic improvement programs.

Conclusions

In this study, we observed that it is possible to obtain synthetic amphidiploids from sterile hybrids between previously untested A- and B- or K-genome wild species. Species such as A. batizocoi, A. gregoryi, and A. magna can be used as female parents and many A-genome species can be used as male parents in future crosses to introgress desirable genes into the cultivated peanut. Most morphological traits in the amphihaploid and amphidiploid hybrids were distinguished by size, where the gigantism effect was observed in the amphidiploids. In Arachis, it is possible to differentiate between diploid and tetraploid plants based on stomata size and count as it is also possible to generate hybrids from crosses between A. hypogaea and new fertile synthetic amphiploids, producing new hybrid combinations and enhancing the genetic variability for use in genetic improvement programs. The morphological characterization showed that there is genetic diversity between hybrids and their respective parents.

Acknowledgments

A.P.F. and N.A.V. thank the Foundation for Research Support of the State of São Paulo (FAPESP) for providing grants and financial assistance. J.F.M.V. and N.A.V. thank the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for providing research grants and financial assistance.

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Everaldo Gonçalves de Barros

References

- Beck SL, Dunlop RW, Fossey A. Stomatal length and frequency as a measure of ploidy level in black wattle, Acacia mearnsii (de Wild) Botl J Linn Soc. 2003;141:177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Burow MD, Simpson CE, Starr JL, Paterson AH. Transmission genetics of chromatin from a synthetic amphidiploid to cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.): Broadening the gene pool of a monophyletic polyploid species. Genetics. 2001;159:823–837. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.2.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz CD, Regazzi AJ. Modelos Biométricos Aplicados ao Melhoramento Genético. 2nd ed. UFV; Viçosa: 1997. 390 [Google Scholar]

- Cunha FB, Nobile PM, Hoshino AA, Moretsohn MC, Lopes CR, Gimenes MA. Genetic relationships among Arachis hypogaea L. (AABB) and diploid Arachis species with AA and BB genomes. Gen Res Crop Evol. 2008;55:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fávero AP, Cuco SM, Aguiar-Perecin MRL, Valls JFM, Vello NA. Rooting in leaf petioles of Arachis for cytological analysis. Cytologia. 2004;69:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Fávero AP, Simpson CE, Valls JFM, Vello NA. Study of the evolution of cultivated peanut through crossability studies among Arachis ipäensis, A. duranensis, and A. hypogaea . Crop Sci. 2006;46:1546–1552. [Google Scholar]

- Fávero AP, Moraes SA, Garcia AAF, Valls JFM, Vello NA. Characterization of rust, early and late leaf spot resistance in wild and cultivated peanut germplasm. Sci Agric. 2009;66:110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández A, Krapovickas A. Cromosomas y evolución en Arachis(Leguminosae) Bonplandia. 1994;8:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Friend SA, Quandt D, Tallury SP, Stalker HT, Hilu KW. Species, genomes, and section relationships in the genus Arachis (Fabaceae): A molecular phylogeny. Plant Syst Evol. 2010;290:185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Guok HP, Wynne JC, Stalker HT. Recurrent selection within a population from an interspecific peanut cross. Crop Sci. 1986;26:249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook CC, Stalker HT. Peanut breeding and genetics resources. Plant Breed Rev. 2003;22:297–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hussaini SH, Goodman MM, Timothy DH. Multivariate analysis and the geographical distribution of the world collection of finger millet. Crop Sci. 1997;17:257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Husted L. Cytological studies of the peanut Arachis. 1. Chromosome number and morphology. Cytologia. 1933;5:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Husted L. Cytological studies of the peanut Arachis. 2. Chromosome number, morphology and behavior, and their application to the problem of the origin of the cultivated forms. Cytologia. 1936;7:396–423. [Google Scholar]

- IBPGR . Preliminary descriptors for Arachis (IBPGR/ICRISAT) - International Crop Network Series. 2. Report on a workshop of the genetic resources of wild Arachis species. International Board for Plant Genetic Resources; Rome: 1990. p. 125. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, Patancheru. [Google Scholar]

- Kermani MJ, Sarasan V, Roberts AV, Yokoya K, Wentworth J, Sieber VK. Oryzalin-induced chromosome doubling in Rosa and its effect on plant morphology and pollen viability. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;107:1195–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1374-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochert G, Halward T, Branch WD, Simpson CE. RFLP variability in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) cultivars and wild species. Theor Appl Genet. 1991;81:565–570. doi: 10.1007/BF00226719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochert G, Stalker HM, Gimenes M, Galgaro L, Lopes CR, Moore K. RFLP and cytogenetic evidence on the origin and evolution of allotetraploid domesticated peanut, Arachis hypogaea(Leguminosae) Am J Bot. 1996;83:1282–1291. [Google Scholar]

- Krapovickas A, Gregory WC. Taxonomia del género Arachis(Leguminosae) Bonplandia. 1994;8:1–186. [Google Scholar]

- Lavia GI. Karyotypes of Arachis palustris and A. praecox (Section Arachis), two species with basic chromosome number n=9. Cytologia. 1998;63:177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Mallikarjuna N, Senthilvel S, Hoisington D. Development of new sources of tetraploid Arachisto broaden the genetic base of cultivated groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Genetic Res Crop Evol. 2011;58:889–907. [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Thompson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular-weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimura M, Kato J, Horaguchi H, Mii M, Sakai K, Katoh T. Induction of fertile amphidiploids by artificial chromosome-doubling in interspecific hybrid between Dianthus caryophyllus L. and D. japonicusThunb. Breed Sci. 2006;56:303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Peñaloza APS, Valls JFM. Chromosome number and satellited chromosome morphology of eleven species of Arachis (Leguminosae) Bonplandia. 2005;14:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Raina SN, Mukai Y. Detection of a variabel number of 18S-5.8S-26S and 5S ribosomal DNA loci by fluorescent in situ hybridization in diploid and tetraploid Arachis species. Genome. 1999a;42:52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Raina SN, Mukai Y. Genomic in situ hybridization in Arachis(Fabaceae) identifies the diploid wild progenitors of cultivated (A. hypogaea) and related wild (A. monticola) peanut species. Plant Syst Evol. 1999b;214:251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Raina SN, Rani V, Kojima T, Ogihara Y, Singh KP, Devarumath RM. RAPD and ISSR fingerprints as useful genetic markers for analysis of genetic diversity, varietal identification, and phylogenetic relationships in peanut (Arachis hypogaea) cultivars and wild species. Genome. 2001;44:763–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X, Huang J, Liao B, Zhang X, Jiang H. Genomic affinities of Arachis genus and interspecific hybrids were revealed by SRAP markers. Genet Res Crop Evol. 2010;57:903–913. [Google Scholar]

- Robledo G, Seijo G. Species relationships among the wild B genome of Arachis species (section Arachis) based on FISH mapping of rDNA loci and heterochromatin detection: A new proposal for genome arrangement. Theor Appl Genet. 2010;121:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00122-010-1369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari N, Abak K, Pitrat M. Comparison of ploidy level screening methods in watermelon: Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum and Nakai. Sci Hort. 1999;82:265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Seijo JG, Lavia GI, Fernández A, Krapovickas A, Ducasse D, Moscone EA. Physical mapping of the 5S and 18S-25S rRNA genes by fish as evidence that Arachis duranensis and A. ipaënsis are the wild diploid progenitors of A. hypogaea . Am J Bot. 2004;91:1294–1303. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.9.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CE. Pathways for introgression of pest resistance into Arachis hypogaea L. Peanut Sci. 1991;18:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CE. Abstract Simposio Latino-Americano de Recursos Genéticos Vegetais. IAC; Campinas: 1997. Introgression of root-nematode resistance into Arachis. p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CE, Starr JL. Registration of ‘Coan’ peanut. Crop Sci. 2001;41:918. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CE, Krapovickas A, Valls JFM. History of Arachis including evidence of A. hypogaea L. progenitors. Peanut Sci. 2001;28:78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK, Stalker HT, Moss JP. Cytogenetics and use of alien genetic variation in groundnut improvement. In: Tsuchiya T, Gupta PK, editors. Chromosome Engineering in Plants: Genetics, Breeding, Evolution. Part B. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1991. pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Singh AK. Utilization of wild relatives in the genetic improvement of Arachis hypogaea L. 8. Synthetic amphidiploids and their importance in interspecific breeding. Theor Appl Genet. 1986;72:433–439. doi: 10.1007/BF00289523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singsit C, Ozias-Akins P. Rapid estimation of ploidy levels in in vitro-regenerated interspecific Arachis hybrids and fertile triploids. Euphytica. 1992;64:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Stalker HT. Utilizing wild species for crop improvement. In: Stalker HT, Chapman C, editors. IBPGR Training Courses: Lecture Series, 2 Scientific Management of Germplasm: Characterization, Evaluation and Enhancement. International Board for Plant Genetic Resources; Rome: 1989. pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Stalker HT, Dhesi JS, Parry DC, Hahn JH. Cytological and interfertility relationships of Arachis Section Arachis . Am J Bot. 1991;78:238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Stalker HT, Moss JP. Speciation, citogenetics and utilization of Arachis species. Advanc Agron. 1987;41:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Stalker HT, Wynne JC, Company M. Variation in progenies of an Arachis hypogaea x diploid wild species hybrid. Euphytica. 1979;28:675–684. [Google Scholar]

- Tallury SP, Hilu KW, Milla SR, Friend SA, Alsaghir M, Stalker HT, Quandt D. Genomic affinities in Arachis section Arachis (Fabaceae): Molecular and cytogenetic evidence. Theor Appl Genet. 2005;111:1229–1237. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco SB, Battistin A, Valls JFM. Diâmetro dos grãos de pólen e tamanho dos estômatos em acessos diplóides e tetraplóides de Hemarthria altissima (Poiret) Stapf & Hubbard (Gramineae) Ciênc Rural. 1999;29:273–76. [Google Scholar]

- Valls JFM, Simpson CE. New species of Arachis L. (Leguminosae) from Brazil, Paraguay and Bolivia. Bonplandia. 2005;14:35–63. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenhout H, Ortiz R, Vuylsteke D, Swennen R, Bai KV. Effect of ploidy on stomatal and other quantitative traits in plantain and banana hybrids. Euphytica. 1995;83:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Wang CT, Wang XZ, Tang YY, Chen DX, Cui FG, Zhang JC, Yu SL. Phylogeny of Arachis based on internal transcribed spacer sequences. Genet Res Crop Evol. 2011;58:311–319. [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- Martins R. Amendoim: Produção, exportação e a safra 2011/2012. Anál Ind do Agron. 2011;2011;6(11) http://www.iea.sp.gov.br/out/LerTexto.php?codTexto=12242. (22 May 2013). [Google Scholar]

- USDA 2013a. United State Department of Agriculture (USDA), http://www.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/psdreport.aspx?hidReportRetrievalName=BVS&hidReportRetrievalID=918&hidReportRetrievalTemplateID=1(August 5, 2013).

- USDA 2013b. United State Department of Agriculture (USDA), http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/MannUsda/viewDocumentInfo.do?documentID=1290. Table 46.xls (February 12, 2013).