Abstract

Background and Objective

The literature lacks knowledge about information preferences and decision-making in young prostate cancer patients. This study provides insight into information sources consulted and factors dictating treatment decision-making in young prostate cancer patients.

Methods

Subjects were identified from pathology consult service of a National Center of Excellence. Questionnaires were mailed to 986 men, under 50 years of age, diagnosed with Gleason score 6 prostate cancer between 2001 and 2005.

Results

Four hundred ninety-three men responded. The most common primary therapies were surgery 397 (81.4%), radiation 52 (10.7%), and active surveillance (AS) 26 (5.3%). Participants with at least some college education (P = 0.003) or annual income >$100,000 (P = 0.003) were more likely to consult three or more doctors. Amongst all treatments, “doctor's recommendation” was the most influential information source, although relatively less important in the AS group. Internet was the second most frequent information source. Participants with higher education (P = 0.0003) and higher income (P = 0.002) considered sexual function more important while making a treatment choice. Only 2% of the men preferred a passive role in the decision-making. Informed decision-making was preferred more by patients who chose radiation and AS while shared decision-making was preferred more by surgery patients (P < 0.05). The majority (89%) of the respondents did not regret their decision. No difference in satisfaction levels was found between different treatment modalities.

Conclusions

This study provides insight into information sources consulted, such as the greater internet use, and various factors dictating treatment decision-making in young prostate cancer patients. There was an overall very high satisfaction rate regardless of the therapy chosen.

Keywords: information seeking, decision-making, prostate cancer

Introduction

Relatively few studies evaluating information seeking behavior and decision-making preferences have been done in prostate cancer patients [1–9]. All the studies were done in older men with a mean age well above 60 years. Prior studies have not explored the treatment-related preferences of the unique subset of young (<50 years) prostate cancer patients. These young patients face the dilemma of balancing the need for definitive curative therapy given their long life expectancy, against the chance of therapy associated morbidity, such as impotence and incontinence that impacts their quality of life to a relatively greater extent than the typical older prostate cancer patient.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instrument

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, a 48-item five-page questionnaire examining information-seeking behavior and decision-making preferences of prostate cancer patients was designed. Questions pertained to: (1) patient demographics, treatment, and serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels (15 questions); (2) information sources used by patients (11 questions); (3) decision-making process (16 questions); and (4) post-decision-making satisfaction (6 questions). To determine patient's role in decision-making, they were asked if they preferred “Shared decision-making”—decision made between physician and myself; “Informed decision-making”— decision made by myself based on various sources of information; or relied on physician to make decision.

Study Population

Consecutive men (1,551) under 50 years of age diagnosed with Gleason score 6 clinically localized prostate cancer were identified from the consult service of one of the authors (J.I.E.) at The Johns Hopkins Department of Pathology between 2001 and 2005. Current addresses were obtained for 986 (64%) patients and the surveys were mailed in August 2008. After 3 months, the surveys were re-mailed to patients who did not respond.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Analysis Software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NY). Means were compared between groups using the t-test, analysis of variance or their non-parametric alternatives if the distribution could not be normalized. Proportions were compared using chi-square tests for contingency tables.

Results

Four hundred ninety-three responses (50%) were obtained. Two patients had died due to unrelated causes and the questionnaires were returned by the wives. Two patients refused to participate and one patient answered fewer than 50% of the questions and was dropped. The remaining 488 questionnaires (>80% questions answered) were considered for analysis.

Three hundred ninety-seven (81.4%) and 52 (10.7%) of the participants chose “Surgery” and “Radiation,” respectively, as their primary therapy while 26 (5.3%) opted for “Active Surveillance” (AS). The remaining 13 (2.7%) men (4 cryosurgery, 3 hormonal ablation alone, and 6 no option checked) were categorized as “Others.”

Treatment Selection: Demographics

Table I describes the patient demographics. Among demographic attributes, only marital status was significantly associated with treatment, with more married men choosing surgery or radiation than AS (P < 0.002). Serum PSA levels at diagnosis were lower in AS patients compared to patients undergoing surgery or radiation, P = 0.014.

Table I. Patient Demographics Stratified by Treatment.

| Participant characteristics | Surgery (n = 397) | Radiation (n = 52) | Active surveillance (n = 26) | Other treatments (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (min–max) in years | 45.7 (31–50) | 46.6 (35–50) | 46.6 (38–50) | 42.9 (41–49) |

| Race (n = 480) | ||||

| White (%) | 350 (90.0) | 42 (80.8) | 25 (96.2) | 12 (92.3) |

| Non-white (%) | 39 (10.0) | 10 (19.2) | 1 (3.9) | 1 (7.7) |

| Marital status (n = 486) | ||||

| Married (%) | 348 (87.9) | 42 (82.4) | 16 (61.5) | 9 (69.2) |

| Non-married (%) | 48 (12.1) | 9 (17.7) | 10 (38.5) | 4 (30.80) |

| Education (n = 486) | ||||

| High school and under (%) | 49 (12.4) | 7 (13.8) | 3 (11.6) | 1 (7.7) |

| College (%) | 110 (27.8) | 14 (27.5) | 5 (19.2) | 4 (30.8) |

| Grad School (%) | 237 (59.9) | 30 (58.8) | 18 (69.2) | 8 (61.5) |

| Employment (n = 485) | ||||

| Employed (%) | 376 (95.4) | 48 (92.3) | 25 (96.2) | 12 (92.3) |

| Unemployed (%) | 18 (4.6) | 4 (7.7) | 1 (3.9) | 1 (7.7) |

| Household income (n = 472) | ||||

| <$100,000 (%) | 177 (45.7) | 19 (40.4) | 14 (53.9) | 4 (33.3) |

| >$100,000 (%) | 210 (54.3) | 28 (59.6) | 12 (46.2) | 8 (66.7) |

| Family history of prostate cancer (n = 485) | ||||

| Positive (%) | 165 (41.7) | 18 (36.0) | 14 (53.9) | 8 (61.5) |

| Negative (%) | 231 (58.3) | 32 (64.0) | 12 (46.2) | 5 (38.5) |

| Mean PSA (ng/ml) (range) | 7.8 (0–800.0) | 5.4 (0.7–16.0) | 3.6 (0.8–9.7) | 6.1 (0–11.4) |

Information-Seeking After Diagnosis

Table II describes the various information sources used by the participants and the role of physicians in providing information. Most patients consulted multiple information sources, with no difference among the treatment groups. Physicians were cited as an information source somewhat more frequently among whites than non-whites (97% vs.90%, P = 0.04). The frequency with which physicians were cited also increased with education, P = 0.036. Similarly, the frequency increased with income, with 88% of those with annual incomes <$50,000 compared to 97% of those with incomes ≥$50,000, P = 0.029. Over half of the participants consulted >3 doctors before deciding on their therapy. Participants with at least some college education (P = 0.003) or annual income >$100,000 (P = 0.003) were more likely to consult three or more doctors while making a decision. Patients who chose AS made more consultation visits before initiating treatment than patients who chose surgery (P = 0.01).

Table II. Information Sources Used and Role of Physicians in Treatment Decisions-Making.

| % of respondents | |

|---|---|

| Information sources used (n = 482)a | |

| Urologist | 96 |

| Internet | 58 |

| Spouse | 50 |

| Primary care/other physician | 41 |

| Radiation oncologist | 26 |

| Medical oncologist | 15 |

| Nurse, other family members, friends, printed material, TV | Small percentage for each |

| No. of information sources used (n = 482) | |

| ≤3 | |

| >3 | |

| Doctors consulted before treatment (n = 477) | |

| 1 | 11 |

| ≥3 | |

| ≥4 | |

| ≥5 | |

| Consultation visits before treatment (n = 463) | |

| 1 | 10 |

| ≥3 | |

| ≥5 | |

| Treatment options discussed by doctora | |

| Surgery (n = 479) | 99 |

| Brachytherapy (n = 476) | 88 |

| External beam radiation therapy (n = 475) | 78 |

| Watchful waiting (n = 474) | 75 |

| Only one treatment endorsed by doctors (n = 475) | |

| Yes | 81 |

| Side effects discussed by doctor (n = 477) | |

| Yes | 98 |

| Doctors recommended against watchful waiting (n = 475) | |

| Yes | 76 |

Patients could choose more than one answer.

Among patients whose physicians endorsed a single treatment, 91% received a recommendation for surgery and while only 4% were recommended radiation. Among patients who chose surgery, 79% said that the doctors recommended against AS, while only 42% of patients who chose AS said that the doctors recommended against AS (P < 0.0001).

Treatment Decision-Making: Most Influential Factor

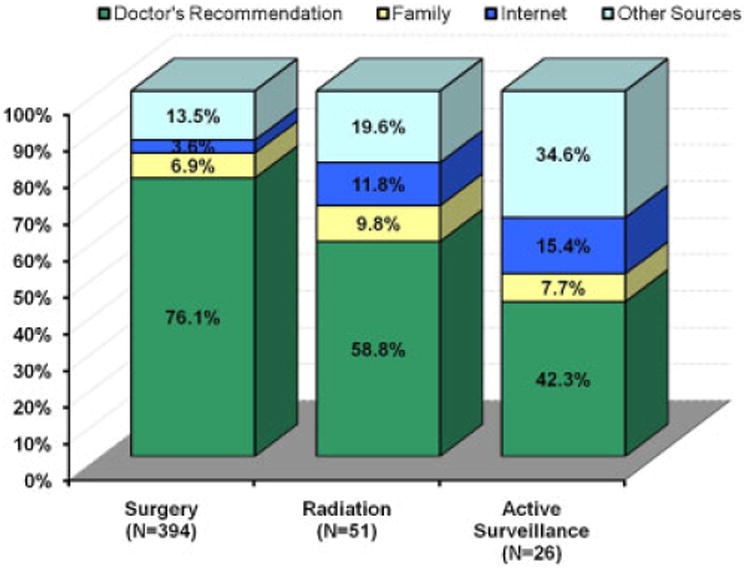

Figure 1 depicts the most influential factors in making treatment decisions; these factors differed significantly among the treatment groups, P < 0.0001. Although “doctor's recommendation” was the most influential factor regardless of treatment group, it was cited by fewer AS patients than surgery or radiation patients. Conversely, “other sources” including media, articles in medical journals, books, and discussion with someone they knew who had the same treatment were relatively more influential for men selecting AS.

Fig. 1.

The most influential factors in making treatment decisions.

Concern for Side-Effects

Ninety percent of the respondents were concerned about sexual function while 84% for urinary function, and 66% for bowel function. Participants with college or higher education level (P = 0.0003) and income over $100,000 (P = 0.002) considered sexual function more influential in treatment choice than incontinence. Incontinence was more influential for high school educated patients compared to those with higher education (P = 0.009).

Reasons for Selecting a Treatment

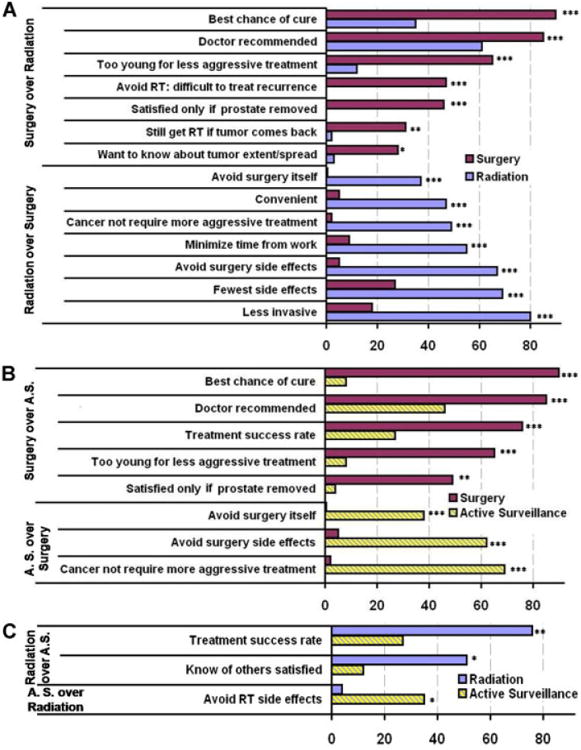

Reasons that occurred significantly more frequently among one treatment group than another are depicted in Figure 2. “Doctor's recommendation” was most commonly cited regardless of treatment group.

Fig. 2.

Reasons for selecting a treatment. A: Surgery versus radiation. B: Surgery versus active surveillance. C: Radiation versus active surveillance. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Patient Role in Decision-Making

Only 2% of the men preferred a passive role, that is, relying solely on the physician, in treatment decision-making. 52.3% preferred “Shared decision-making between physician and myself” while 45.8% preferred “Informed decision made by myself based on information.” Better educated men preferred “Informed decision-making” over “Shared decision-making” (P = 0.011). Informed decision-making was also preferred more by patients who chose radiation and AS while shared decision-making was preferred more by surgery patients (P = 0.0004).

Post-Treatment Satisfaction

The majority (89%) of patients did not regret their decision. Feelings of regret after treatment were higher in those with high school or college education compared to graduate school education (P = 0.007) and those with lower income (P < 0.0001). Non-married patients found the decision more difficult to make (P = 0.032), were more worried (P = 0.0005) and experienced more distress (P = 0.011) while making treatment decisions. Patients choosing radiation found the decision more difficult to make than patients who chose surgery (P = 0.0007). Patients who chose AS were more worried whether they made the right decision than patients who chose surgery (P = 0.009). No difference in satisfaction levels was found between different treatment modalities.

Discussion

Most patients with prostate cancer are relatively old with a median age of 67. Data from SEER show that for men either 30 or 40 years of age, there is only a 0.3% risk in each cohort of developing clinical cancer by age 50 [10]. In a study of 324,684 prostate needle biopsies (1995–2002), only 3.7% were received in 2001 from men <50 years of age [11]. The detection rate of cancer per biopsy was 0.08% and 1.9% of men aged 30–39 and 40–49, respectively. This contrasts with rates of 13.5%, 34%, and 39% for men aged 50–59, 60–69, and 70–79, respectively.

When confronted with prostate cancer, men are often bewildered by the numerous treatment options, none which have been definitively proven to be superior. These treatment decisions are potentially harder for young men with prostate cancer given the greater impact therapy will have due to their longer life expectancy. Furthermore, issues relating to preserving sexual function are likely more influential in younger men. Young patients, thus, actively seek information from multiple information sources and multiple physicians before ultimately deciding on their therapy. Men with higher education and income consulted an increased number of physicians while making a decision. The information sources used by the participants in our study are similar to those described by Ramsey et al. [8], where urologists are the most common information source. The younger men in our study used the internet for information (58%) more than older prostate cancer patients in prior studies from Canada (29%), Australia (40%), and the United States (33%) [3,12,13]. More than half of the patients consulted their family and friends before making decisions thus emphasizing the role of social support. Non-married men in our study found treatment-related decisions more difficult to make and were more worried about their decision, further highlighting the importance of social support. Christie et al. [14] also reported better coping with prostate cancer diagnosis in patients who spent greater time talking to family and friends about their options.

As expected, surgery was chosen by the majority of young men with prostate cancer. There was less physician support to select radiation. As in other studies done in older men, younger patients considered doctor's recommendation as the most influential factor in decision-making [7,9]. Urologists typically recommend surgery in young men with prostate cancer due to their long life expectancy and the assumption that this offers the best chance of long-term cure. The most common reason patients chose surgery was the perception that it provided the best chance of cure, similar to studies in older patients [15]. Whereas surgery was discussed as a treatment option in 99% of cases, brachytherapy, external beam radiotherapy, and AS were discussed in only 88%, 78%, and 75% of cases, respectively. Physicians recommended against AS in 75% of cases.

While it is not surprising that surgery was favored over AS because the latter was considered less aggressive treatment, many younger patients also felt that radiation was less aggressive therapy than surgery. Another perceived advantage of surgery over radiation was the difficulty of treating disease if tumor recurred after radiation. Almost half of the patients cited that they were satisfied only if the prostate was removed from their body, a belief shared by older men [5]. Approximately one-third men cited that by having a prostatectomy they would have accurate knowledge of tumor extent.

Men choosing radiation or AS, in addition to the desire to avoid surgery side effects, also cited general avoidance of surgery as a factor into their decision. The less invasive nature of radiation therapy was the primary reason for choosing this treatment as opposed to prostatectomy, similar to what has been reported in older men [5].

In several studies of prostate cancer patients with mean ages in the mid 60s, fear of incontinence as opposed to impotence was a greater factor in their decision-making [5,16]. The current study showed that younger patients placed more importance on sexual function than urinary function when choosing treatment. We also found that sexual function was relatively more valued in the decision process in patients with higher education and with higher income. Incontinence was a more influential factor for less educated patients. One possible explanation is that less educated patients may have jobs involving manual labor, which would be more affected by incontinence. In patients with higher education, lifestyle issues such as potency could play a greater role in their decision-making. In the current study, cost of treatment was not an important factor in treatment decision-making in younger men, similar to what has been found in older men [16–19].

In two studies published in 1995 and 2002 from the same investigators, 40% and 92.5% of prostate cancer patients, respectively, preferred an active or collaborative role in decision-making [20,21]. The difference was attributed to younger age (mean age 71 years vs. 61 years) of the patients in the second study. In our study, 98% preferred an active or collaborative role in the decision-making, reflecting even younger patients. Active decision-making was approximately equally split between a “shared decision-making” between the physician and patient as opposed to “informed decision-making” made by the patient using various sources of information. Shared decision-making has been correlated with literacy [22]. Not surprisingly, informed decision requiring an even more active investigation of treatment choices occurred more frequently among men with graduate level education. In addition, men who chose radiation or AS preferred informed decision. These men often received conflicting opinions as to what treatment they should undergo, requiring informed decision to decide amongst the choices.

One of the limitations of the study is lack of detailed information on the non-responders (subjects being consults), many of whom may have never received the survey. Nevertheless, it is likely that patients in the current study are representative of early prostate cancer in general in young men in terms of their disease and eventual treatment selected. In these young men with Gleason 6 cancer, cases were typically sent for consultation either by the urologist or the pathologist not because of the difficulty of the pathologic diagnosis but as a result of the desire to have expert confirmation of prostate cancer in such young men. The majority of studies analyzing treatment decisions in men with prostate cancer consist are small (<100 men) with a mean age in their mid 60s [9]. Our ability to analyze data from approximately 500 men with prostate cancer diagnosed before age of 50 is a result of reviewing approximately 15,000 prostate needle biopsy cases annually in our service. By considering only men diagnosed during a recent 5-year time interval we minimized confounding due to secular trends.

By including men with a uniform Gleason score, differences in disease aggressiveness as a contributing factor to treatment decisions present in other studies could be minimized [3]. Also since all men had clinically localized Gleason 6 cancer, all therapies were potentially viable. If we had included higher grade disease, AS would not have been a treatment option. Other potential biases were removed by including cases from a large number of physicians and geographical areas. Examples of single or limited multi-institution studies with selection bias include ones where institutions focused on radiation therapy, or only compared radiation to brachytherapy [5,12,23].

Another major limitation is recall bias because of the retrospective nature of the study, which has been demonstrated in older men with prostate cancer [24]. The design of the study with a relatively short diagnosis interval minimized the differences between those diagnosed from 2001 to 2005 relative to their recall in answering the questionnaire in 2008. A 3-year interval from the last date of diagnosis to the time of questionnaire submission was selected to ascertain patient satisfaction with their treatment choice, as it may take a year or more for certain post-therapy morbidities to improve and stabilize.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into information sources consulted by young prostate cancer patients, such as the greater use of the internet. It also highlights various factors dictating treatment decision-making in this population. Physicians should inform patients of the relative advantages and disadvantages of the various therapies, especially those that are most influential in the decision-making process. It is encouraging that almost all patients considered that they played either an active or collaborative role in their decision, as opposed to passively accepting what was dictated to them by the physician. Finally, despite the distress associated with being diagnosed with prostate cancer at such a young age, there was an overall very high satisfaction rate with their treatment regardless of the therapy chosen.

References

- 1.Cegala DJ, Bahnson RR, Clinton SK, David P, Gong MC, Monk JP, III, Nag S, Pohar KS. Information seeking and satisfaction with physician-patient communication among prostate cancer survivors. Health Commun. 2008;23(1):62–69. doi: 10.1080/10410230701806982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berry DL, Ellis WJ, Woods NF, Schwien C, Mullen KH, Yang C. Treatment decision-making by men with localized prostate cancer: The influence of personal factors. Urol Oncol. 2003;21(2):93–100. doi: 10.1016/s1078-1439(02)00209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steginga SK, Occhipinti S, Gardiner RA, Yaxley J, Heathcote P. Making decisions about treatment for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2002;89(3):255–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry DL, Ellis WJ, Russell KJ, Blasko JC, Bush N, Blumenstein B, Lange PH. Factors that predict treatment choice and satisfaction with the decision in men with localized prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2006;5(3):219–226. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2006.n.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmboe ES, Concato J. Treatment decisions for localized prostate cancer: Asking men what's important. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(10):694–701. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.90842.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong F, Stewart DE, Dancey J, Meana M, McAndrews MP, Bunston T, Cheung AM. Men with prostate cancer: Influence of psychological factors on informational needs and decision making. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel HR, Mirsadraee S, Emberton M. The patient's dilemma: Prostate cancer treatment choices. J Urol. 2003;169(3):828–833. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000052056.27609.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramsey SD, Zeliadt SB, Arora NK, Potosky AL, Blough DK, Hamilton AS, Van Den Eeden SK, Oakley-Girvan I, Penson DF. Access to information sources and treatment considerations among men with local stage prostate cancer. Urology. 2009;74(3):509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.01.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeliadt SB, Ramsey SD, Penson DF, Hall IJ, Ekwueme DU, Stroud L, Lee JW. Why do men choose one treatment over another? : A review of patient decision making for localized prostate cancer. Cancer. 2006;106(9):1865–1874. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horner MJRL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Feuer EJ, Huang L, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Lewis DR, Eisner MP, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006. Vol. 2010. Bethseda: Cancer Statistics Branch of the NCI; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowe FC, Gilbert SM, Kahane H. Evidence of increased prostate cancer detection in men aged 50 to 59: A review of 324,684 biopsies performed between 1995 and 2002. Urology. 2003;62(6):1045–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00782-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall JD, Boyd JC, Lippert MC, Theodorescu D. Why patients choose prostatectomy or brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer: Results of a descriptive survey. Urology. 2003;61(2):402–407. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pautler SE, Tan JK, Dugas GR, Pus N, Ferri M, Hardie WR, Chin JL. Use of the internet for self-education by patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;57(2):230–233. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Christie KM, Meyerowitz BE, Giedzinska-Simons A, Gross M, Agus DB. Predictors of affect following treatment decision-making for prostate cancer: Conversations, cognitive processing, and coping. Psycho-oncology. 2009;18(5):508–514. doi: 10.1002/pon.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazur DJ, Hickam DH. Patient preferences for management of localized prostate cancer. West J Med. 1996;165(1–2):26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Van Manen L, Svenson O. Patient-focussed decision-making in early-stage prostate cancer: Insights from a cognitively based decision aid. Health Expect. 2004;7(2):126–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford ED, Bennett CL, Stone NN, Knight SJ, DeAntoni E, Sharp L, Garnick MB, Porterfield HA. Comparison of perspectives on prostate cancer: Analyses of survey data. Urology. 1997;50(3):366–372. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demark-Wahnefried W, Schildkraut JM, Iselin CE, Conlisk E, Kavee A, Aldrich TE, Lengerich EJ, Walther PJ, Paulson DF. Treatment options, selection, and satisfaction among African American and white men with prostate carcinoma in North Carolina. Cancer. 1998;83(2):320–330. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980715)83:2<320::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman-Stewart D, Brundage MD, Hayter C, Groome P, Nickel JC, Downes H, Mackillop WJ. What questions do patients with curable prostate cancer want answered? Med Decis Making. 2000;20(1):7–19. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0002000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davison BJ, Degner LF, Morgan TR. Information and decision-making preferences of men with prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(9):1401–1408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davison BJ, Gleave ME, Goldenberg SL, Degner LF, Hoffart D, Berkowitz J. Assessing information and decision preferences of men with prostate cancer and their partners. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25(1):42–49. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200202000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SP, Knight SJ, Tomori C, Colella KM, Schoor RA, Shih L, Kuzel TM, Nadler RB, Bennett CL. Health literacy and shared decision making for prostate cancer patients with low socioeconomic status. Cancer Invest. 2001;19(7):684–691. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100106143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diefenbach MA, Dorsey J, Uzzo RG, Hanks GE, Greenberg RE, Horwitz E, Newton F, Engstrom PF. Decision-making strategies for patients with localized prostate cancer. Semin Urol Oncol. 2002;20(1):55–62. doi: 10.1053/suro.2002.30399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miles BJ, Giesler B, Kattan MW. Recall and attitudes in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 1999;53(1):169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]