Abstract

Objective

Previous reports of RAPID-PsA (NCT01087788) demonstrated efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol (CZP) over 24 weeks in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA), including patients with prior antitumour necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. We report efficacy and safety data from a 96-week data cut of RAPID-PsA.

Methods

RAPID-PsA was placebo-controlled to week 24, dose-blind to week 48 and open-label to week 216. We present efficacy data including American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) responses, HAQ-DI, pain, minimal disease activity (MDA), modified total Sharp score (mTSS) and ACR responses in patients with/without prior anti-TNF exposure, in addition to safety data.

Results

Of 409 patients randomised, 273 received CZP from week 0. 54 (19.8%) CZP patients had prior anti-TNF exposure. Of patients randomised to CZP, 91% completed week 24, 87% week 48 and 80% week 96. ACR responses were maintained to week 96: 60% of patients achieved ACR20 at week 24, and 64% at week 96. Improvements were observed with both CZP dose regimens. ACR20 responses were similar in patients with (week 24: 59%; week 96: 63%) and without (week 24: 60%; week 96: 64%) prior anti-TNF exposure. Placebo patients switching to CZP displayed rapid clinical improvements, maintained to week 96. In patients with ≥3% baseline skin involvement (60.8% week 0 CZP patients), PASI responses were maintained to week 96. No progression of structural damage was observed over the 96-week period. In the Safety Set (n=393), adverse events occurred in 345 patients (87.8%) and serious adverse events in 67 (17.0%), including 6 fatal events.

Conclusions

CZP efficacy was maintained to week 96 with both dose regimens and in patients with/without prior anti-TNF exposure. The safety profile was in line with that previously reported from RAPID-PsA, with no new safety signals observed with increased exposure.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Anti-TNF, TNF-alpha, DMARDs (biologic), Psoriatic Arthritis, Spondyloarthritis

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Previous reports of RAPID-PsA demonstrated the efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol (CZP) over 24 weeks for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

What does this study add?

CZP efficacy was maintained to week 96 with both CZP dose regimens and in patients with and without prior antitumour necrosis factor (TNF) exposure.

No clinically relevant progression of structural damage over the long term was demonstrated in patients treated with CZP.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Given that there is an ever increasing number of patients who have been exposed to anti-TNF agents, the data presented here, demonstrating a similar efficacy with CZP regardless of prior anti-TNF exposure, may be used to advise treatment decisions in future clinical practice.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a complex, multifaceted systemic disease associated with a substantial long-term disease burden. Over one-half of patients exhibit progressive, erosive disease with subsequent impairment in clinical function within 2 years of disease onset.1 2 In addition to articular manifestations, which can include peripheral joint disease, enthesitis, dactylitis and axial involvement, patients with PsA often experience a substantial extra-articular burden of disease, including psoriatic skin disease, nail disease and inflammatory bowel disease.

Patients with PsA have significantly impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL) compared to the general population, with patients with PsA who suffer from psoriatic skin involvement having an even greater burden, particularly in terms of the psychosocial aspects of HRQoL.3 4 Given the chronic nature of PsA, it is important to demonstrate the maintenance of short-term benefits over longer periods. This is particularly relevant for objective disease measures such as structural damage, assessed using X-rays, where investigation of the sustained treatment effect is required over a longer period of time.

Certolizumab pegol (CZP) is a PEGylated Fc-free antitumour necrosis factor (TNF) that has been shown to reduce the signs and symptoms of PsA over 24 weeks,5 while providing inhibition of structural damage6 and improvements in patient-reported outcomes (PROs).7 The objective of this publication is to report the safety and efficacy of two CZP dosing regimens in patients with PsA over 96 weeks, as measured by clinical, patient-reported and radiographic outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patient eligibility criteria for the RAPID-PsA trial (NCT01087788) have been reported previously.5 Briefly, patients aged ≥18 years, with active PsA of ≥6 months’ duration, as defined by the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR), were included.8 Patients must have experienced failure to ≥1 disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), and up to 40% of patients could have experienced secondary failure to one prior anti-TNF (loss of efficacy or intolerance to TNF-antagonist treatment). Patients with evidence of latent or active tuberculosis were excluded unless prophylactic treatment of latent tuberculosis had begun at least 4 weeks prior to baseline.

Trial design

Treatment procedures

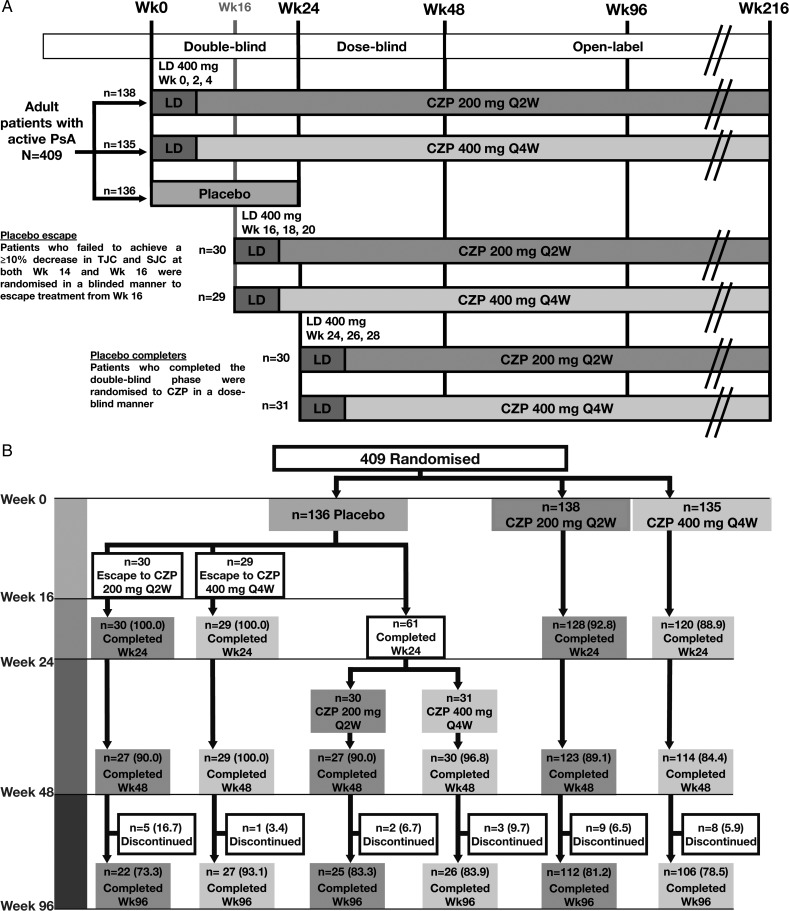

RAPID-PsA is a phase 3 randomised multicentre trial in patients with PsA, which was double-blind and placebo-controlled to week 24, dose-blind to week 48 and an open-label extension (OLE) to week 216. We report data from an interim analysis of the dose-blind period (weeks 24–48) and the first 48 weeks of the OLE (ie, 96 weeks from the study start). Patients were randomised 1:1:1 to placebo, or subcutaneous CZP 400 mg at weeks 0, 2 and 4 (loading dose) followed by either CZP 200 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) or CZP 400 mg every 4 weeks (Q4W) (figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Trial design and (B) Patient disposition to week 96 of the RAPID-PsA trial, and (C) Kaplan-Meier plot of time to withdrawal for any reason, and due to lack of efficacy or adverse events for patients originally randomised to CZP. Data shown for the randomised set. AE, adverse event; CZP, certolizumab pegol; LD, loading dose; Q2W, every 2 weeks; wk, week; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count.

Figure 1.

Continued.

Patients originally randomised to CZP continued on their assigned dose. Placebo patients who failed to achieve ≥10% improvement from baseline in tender and swollen joint counts at both weeks 14 and 16 (early escape) were re-randomised 1:1 at week 16 to CZP 200 mg Q2W or CZP 400 mg Q4W, following CZP loading dose (figure 1A). The remaining placebo patients were re-randomised to CZP at week 24 in a similar manner.

Original randomisation was stratified by investigator site and prior anti-TNF exposure, based on an interactive voice response system. At all study sites, all investigators and other healthcare professionals involved in safety or efficacy assessments were completely blind to the study medications. Owing to some differences in the presentation and viscosity of CZP and placebo, all study treatments were administered by dedicated, unblinded, trained study centre personnel with no other involvement in the study, to maintain study blinding. Strict rules were applied to limit and control the communication between the blinded healthcare professionals, the local unblinded study centre personnel and study sponsor personnel.

Evaluations

The primary clinical (American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response at week 12) and radiographic (change from baseline in modified total Sharp score (mTSS) at week 24) end points of RAPID-PsA are reported elsewhere.5 6 Efficacy variables were measured to week 96 and included ACR20/50/70 and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75/90/100 response rates. The proportion of patients achieving minimal disease activity (MDA) (defined as patients fulfilling at least 5 of 7 MDA criteria)9 was also analysed.

The Disease Activity Score (28-joint count) based on C-reactive protein (DAS28(CRP)) was used to evaluate joint involvement, and the proportion of patients achieving DAS28(CRP) ≤3.2 is also reported. Other clinical features of PsA included enthesitis (Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI))10 and dactylitis (Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI)).10 Patient-reported quality of life measures were also reported, including pain (visual analogue scale (VAS)), fatigue (VAS), function (Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; HAQ-DI) and short-form 36-item health survey component summaries (SF-36 mental component summary (MCS) and SF-36 physical component summary (PCS)).

Radiographic damage for patients originally randomised to CZP was assessed to week 96 as part of a third reading campaign, during which radiographs taken at baseline and at weeks 24 and 48 were re-read, in addition to week 96 radiographs (as opposed to using data from the first (24 weeks) or second (48 weeks) reading campaigns). Radiographs were also read for patients originally randomised to placebo who switched to CZP treatment at either week 16 or 24. For these patients, it was of interest to evaluate the change in mTSS while on CZP following their re-randomisation. Therefore, for these patients, mTSS change was assessed from CZP initiation, that is, from their last available radiograph before initiation of CZP treatment (week 12 for patients escaping at week 16, or week 24 for patients switching at week 24).

Safety analyses included all adverse events (AEs) and routine laboratory analyses performed at every trial visit through to week 96.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy results are presented for patients randomised to CZP at baseline, though selected results are presented for patients re-randomised from placebo to CZP. Response rates (%) are calculated considering patient withdrawal and missing evaluation as non-response (non-responder imputation (NRI)). Missing quantitative efficacy assessments were imputed by carrying forward the last observation (LOCF). Selected results are also presented as observed data from those completing the week 96 assessment.

Radiographic outcomes reported include mTSS11 change from baseline (for patients originally randomised to placebo who switched to CZP, mTSS change was assessed relative to their last available radiograph before initiation of CZP treatment) and the percentage of patients with mTSS non-progression (defined either as change from baseline in mTSS ≤0 or ≤0.5). Radiographic outcomes were estimated for patients originally randomised to CZP, for patients originally randomised to placebo who switched to CZP, and for subgroups of patients at low or high risk of further structural progression (defined as a baseline mTSS above (>) or below (≤) the median baseline mTSS of 3.5).

Progression of mean mTSS was analysed using a mixed effect model for repeated measures (MMRM) with mTSS as the dependent variable, where treatment regimen and visit were fixed-effect factors, with treatment regimen by visit as an interaction term. Actual mTSS values, rather than change from Baseline, were analysed to allow the inclusion of all available mTSS assessments in the analysis, even if the Baseline assessment was missing. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to account for within-subject correlation. Data are presented as the least squares mean with 95% CIs or as the percentage of patients with mTSS non-progression.

Clinical efficacy data were summarised descriptively with no inferential statistics. Quantitative efficacy measures over time are summarised by arithmetic mean and SD. Efficacy measures are predominantly presented for the Randomized Set. However, certain efficacy outcomes pertaining to specific disease manifestations are reported in subpopulations of patients suffering from these manifestations. ACR response rates were analysed in all patients and those with and without prior anti-TNF exposure. PASI was measured in patients with ≥3% BSA (body surface area) psoriatic skin involvement at baseline and in a post hoc analysis of patients who additionally had baseline PASI ≥10. LEI was assessed in patients with enthesitis at baseline (LEI ≥1) and dactylitis in patients with dactylitis at baseline (≥1 dactylitic digit with a circumference ≥10% larger compared with the contralateral digit).

Patient retention for CZP patients was summarised with a Kaplan-Meier plot. Furthermore, patient withdrawal due to AEs or loss of efficacy was estimated with a Kaplan-Meier plot in which patients withdrawing for other reasons were censored at the time of withdrawal.

Safety data are presented for all patients treated with at least one dose of CZP at any stage during the 96-week trial period. AE incidences are reported as the proportion of all patients in the Safety Set and in terms of the event rate (ER) per 100 patient-years (PY) of exposure.

Results

Patient population and disposition

A total of 409 patients were randomised, of whom 273 received CZP from week 0 (baseline). Of the patients randomised to CZP at baseline, 248 (90.8%) patients completed to week 24, 237 (86.8%) patients completed to week 48 and 218 (79.9%) patients completed to week 96. Between weeks 24 and 48, 6 of these patients (2.2%) withdrew due to an AE and 3 (1.1%) due to loss of efficacy. Between week 48 and week 96, 7 (2.6%) patients withdrew due to an AE and 5 (1.8%) due to loss of efficacy. The Kaplan-Meier analysis indicates that if only withdrawals due to AEs or loss of efficacy were considered, the estimated retention rate at week 96 was 86.5%, rather than the 79.9% for all withdrawals (figure 1C).

Of 136 patients originally randomised to placebo at baseline, 59 escaped early and were re-randomised to CZP at week 16, while 61 completed the double-blind phase and were re-randomised at week 24 (figure 1B).

Baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups (table 1). It was noted that placebo patients who did not meet escape criteria had lower disease activity at baseline in HAQ-DI (as was also noted in a CZP study in rheumatoid arthritis12), skin disease (PASI) and structural damage (mTSS), when compared to placebo patients who escaped at week 16.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease severity characteristics for patients originally randomised to CZP at week 0 or re-randomised from placebo at weeks 16 and 24 of the RAPID-PsA study

| CZP 200 mg Q2W |

CZP 400 mg Q4W |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 0 CZP (n=138) | PBO→CZP week 16 (n=30) |

PBO→CZP week 24 (n=30) | Week 0 CZP (n=135) | PBO→CZP week 16 (n=29) |

PBO→CZP week 24 (n=31) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age, years | 48.2±12.3 | 48.0±11.6 | 47.8±11.4 | 47.1±10.8 | 49.3±10.0 | 45.0±10.7 |

| Sex, % female | 53.6 | 56.7 | 63.3 | 54.1 | 65.5 | 51.6 |

| Race, % white | 97.8 | 100 | 100 | 98.5 | 96.6 | 93.5 |

| Weight, kg | 85.8±17.7 | 82.8±18.7 | 81.1±16.5 | 84.8±18.7 | 78.9±21.5 | 87.3±23.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.5±6.2 | 28.9±5.5 | 28.5±4.1 | 29.6±6.6 | 28.1±7.0 | 30.9±9.3 |

| Arthritis characteristics | ||||||

| Time from psoriatic arthritis diagnosis,* years | 9.6±8.5 | 7.7±7.3 | 7.3±7.5 | 8.1±8.3 | 10.6±10.3 | 6.3±5.7 |

| CRP† (mg/L), median (minimum–maximum) | 7.0 (0.3–238.0) | 6.5 (0.2–100.0) | 8.7 (0.3–32.3) | 9.1 (0.1–87.0) | 10.3 (1.1–80.7) | 10.3 (0.7–60.0) |

| ESR (mm/h), median (minimum–maximum) | 35.0 (5.0–125.0) | 32.5 (15–91) | 32.0 (20–95) | 33.0 (4.0–120.0) | 35.0 (10–92) | 31.0 (6–70) |

| Tender joint count (0–68 joints) | 21.5±15.3 | 19.4±15.2 | 17.0±13.8 | 19.6±14.8 | 18.4±11.2 | 21.2±16.0 |

| Swollen joint count (0–66 joints) | 11.0±8.8 | 10.0±7.9 | 9.7±7.0 | 10.5±7.5 | 10.0±6.2 | 10.0±7.5 |

| HAQ-DI (range 0–3) | 1.3±0.7 | 1.3±0.6 | 1.2±0.6 | 1.3±0.6 | 1.5±0.6 | 1.1±0.7 |

| Modified total Sharp score | 15.4±27.9 | 25.3±50.2 | 18.5±24.8 | 20.9±45.3 | 37.0±79.2 | 15.5±30.3 |

| Erosion score | 9.4±16.2 | 15.7±29.6 | 10.7±14.0 | 12.9±25.3 | 21.7±43.3 | 9.7±17.4 |

| Joint space narrowing score | 6.0±12.4 | 9.7±20.9 | 7.8±12.0 | 8.0±20.5 | 15.2±36.2 | 5.7±13.5 |

| Psoriasis characteristics | ||||||

| Psoriasis BSA ≥3%, n (%) | 90 (65.2) | 18 (60.0) | 20 (66.7) | 76 (56.3) | 20 (69.0) | 16 (51.6) |

| PASI,‡ median (minimum–maximum) | 7.0 (0.6–72.0) | 9.1 (0.5–20.1) | 4.6 (0.3–20.4) | 8.1 (0.6–51.8) | 7.7 (0.6–37.9) | 6.0 (1.2–36.9) |

| Prior use of synthetic DMARDs, n (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 61 (44.2) | 17 (56.7) | 18 (60.0) | 68 (50.4) | 11 (37.9) | 17 (54.8) |

| ≥2 | 74 (53.6) | 12 (40.0) | 12 (40.0) | 64 (47.4) | 17 (58.6) | 14 (45.2) |

| Concomitant use of NSAIDs to week 96, n (%) | 106 (76.8) | 25 (83.3) | 20 (66.7) | 105 (77.8) | 22 (75.9) | 26 (83.9) |

| Prior anti-TNF exposure, n (%) | 31 (22.5) | 9 (30.0) | 3 (10.0) | 23 (17.0) | 7 (24.1) | 2 (6.5) |

| Concomitant use of MTX to week 96, n (%) | 90 (65.2) | 18 (60.0) | 20 (66.7) | 87 (64.4) | 19 (65.5) | 20 (64.5) |

Data are shown for the Randomised Set. Except where indicated otherwise, values are the mean±SD.

*From the start date of primary disease.

†Normal range of CRP <8.0 mg/L.

‡PASI scores reported for patients with psoriasis body surface area ≥3% at baseline.

BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CRP, C reactive protein; CZP, certolizumab pegol; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; MTX, methotrexate; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PBO, placebo; Q2W, every 2 weeks; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Of patients originally randomised to CZP 200 mg Q2W or CZP 400 mg Q4W, 31 (22.5%) and 23 (17.0%) had prior anti-TNF exposure, respectively (table 1). The most common reason reported for discontinuation of prior anti-TNF treatment was a secondary loss of response (table 2). At baseline, of the 63.7% of CZP-randomised patients taking concomitant methotrexate, the majority (78.7%) received oral medication. The mean (±SD) weekly dose of methotrexate was 17.5 mg±11.4.

Table 2.

Reasons for discontinuation of prior anti-TNF (before enrolment in the RAPID-PsA study)

| Week 0 placebo (n=26) | Week 0 CZP 200 mg Q2W (n=31) | Week 0 CZP 400 mg Q4W (n=23) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior anti-TNF exposure, n (%) | 26 (19.1) | 31 (22.5) | 23 (17.0)* |

| Adalimumab | 13 (9.6) | 10 (7.2) | 10 (7.4) |

| Etanercept | 9 (6.6) | 15 (10.9) | 8 (5.9) |

| Infliximab | 2 (1.5) | 5 (3.6) | 5 (3.7) |

| Golimumab | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Reason for discontinuation of prior anti-TNF, n (%) | |||

| Primary lack of response | 3 (11.5) | 2 (6.5) | 0 |

| Secondary loss of response | 8 (30.8) | 9 (29.0) | 6 (26.1) |

| Intolerance | 2 (7.7) | 5 (16.1) | 0 |

| Partial response | 1 (3.8) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (13.0) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

| Other | 12 (46.2) | 13 (41.9) | 13 (56.5) |

| Bicytopenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

| Bowel perforation | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

| Financial reasons | 4 (15.4) | 7 (22.6) | 5 (21.7) |

| Drug unavailable | 3 (11.5) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (4.3) |

| End of clinical evaluations | 3 (11.5) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (4.3) |

| Insurance reasons | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (13.0) |

| Painful injection site reactions | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 0 |

| Family planning reasons | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Preparation for surgery | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.3) |

Data shown for patients from the randomised set of patients from RAPID-PsA with prior anti-TNF exposure.

*One patient had past use of both adalimumab and etanercept.

CZP, certolizumab pegol; Q2W, every 2 weeks; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Efficacy outcomes

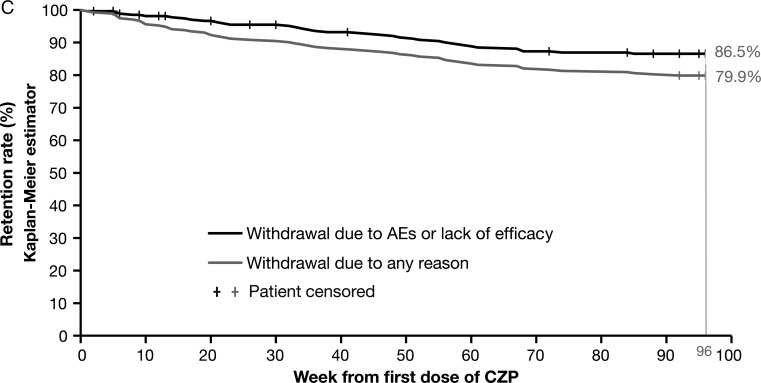

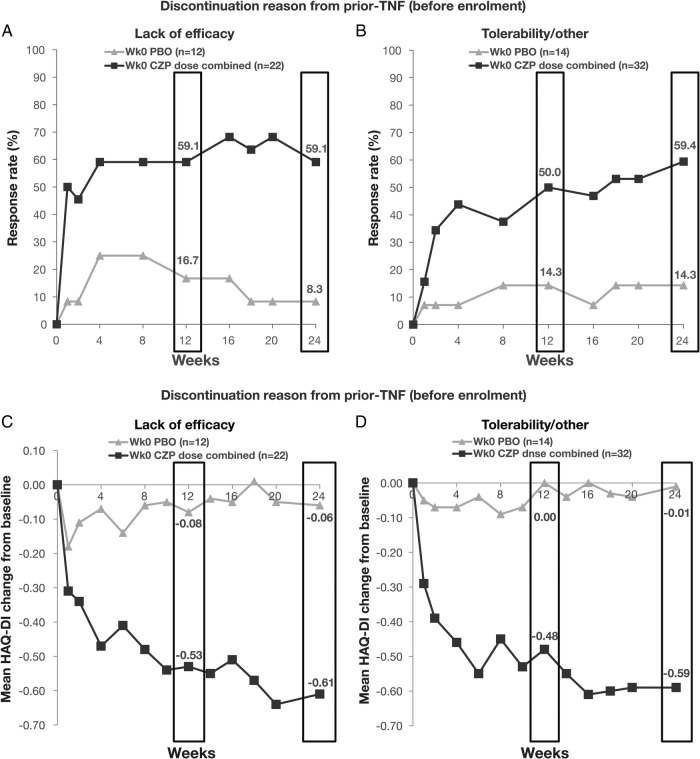

Rapid improvements observed in the 24-week double-blind phase in components of the ACR response (including HAQ-DI and pain, figure 2) were maintained to week 96. Improvements in ACR, observed for both CZP dose regimens over 24 weeks, were maintained to week 48 of the dose-blind phase and to week 96 of the OLE (figure 2A). Imputation of ACR20 response using NRI gave a week 96 response rate of 64% compared to 81% when using observed data (combined CZP doses (table 3)). Similar maintenance of efficacy was observed in continuous disease activity measures such as DAS28(CRP), and in the proportion of patients achieving DAS28 <2.6 or DAS28 ≤3.2 (table 3). Improvements observed to week 24 in MDA, a stringent treatment target that includes joint, skin and patient-reported components, were also maintained to week 96 (table 3).

Figure 2.

Clinical and patient-reported outcomes for patients randomised to CZP 200 mg Q2W and CZP 400 mg Q4W to week 96. (A) ACR response rates; (B) ACR20 response rates for placebo patients re-randomised to CZP; (C) PASI75 and PASI90 response rates for patients with ≥3% BSA psoriasis at baseline; (D) PASI90 response rates for patients with ≥3% BSA psoriasis and PASI ≥10 at baseline; (E) mean HAQ-DI score and (F) mean pain score. Data are shown for the Randomised Set. Missing categorical data were imputed by non-responder imputation; missing continuous measures were imputed by the last observation carried forward. HAQ-DI was scored on a 0–3 scale and pain on a 0–100 numerical rating scale. ACR, American College of Rheumatology; BSA, body surface area; CZP, certolizumab pegol; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; wk, week; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

Table 3.

Clinical outcomes and PROs at weeks 12, 24, 48 and 96 for patients randomised to CZP at baseline (200 mg Q2W and 400 mg Q4W doses combined)

| Week 0 CZP dose combined (N=273) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 12 (imputation) | Week 24 (imputation) | Week 48 (imputation) | Week 96 (imputation) | Week 96 (observed) | ||

| Score | n | |||||

| Clinical outcomes | ||||||

| ACR20, n (%) | 150 (54.9) | 164 (60.1) | 181 (66.3) | 175 (64.1) | 175 (80.6) | 217 |

| TNF-naïve* | 121 (55.3) | 132 (60.3) | 148 (67.6) | 141 (64.4) | 141 (79.2) | 178 |

| TNF-experienced† | 29 (53.7) | 32 (59.3) | 33 (61.1) | 34 (63.0) | 34 (87.2) | 39 |

| ACR50, n (%) | 94 (34.4) | 115 (42.1) | 130 (47.6) | 136 (49.8) | 136 (62.7) | 217 |

| TNF-naïve* | 74 (33.8) | 91 (41.6) | 104 (47.5) | 109 (49.8) | 109 (61.2) | 178 |

| TNF-experienced† | 20 (37.0) | 24 (44.4) | 26 (48.1) | 27 (50.0) | 27 (69.2) | 39 |

| ACR70, n (%) | 51 (18.7) | 71 (26.0) | 89 (32.6) | 95 (34.8) | 95 (43.8) | 217 |

| TNF-naïve* | 39 (17.8) | 57 (26.0) | 71 (32.4) | 77 (35.2) | 77 (43.3) | 178 |

| TNF-experienced† | 12 (22.2) | 14 (25.9) | 18 (33.3) | 18 (33.3) | 18 (46.2) | 39 |

| PASI75, n (%)‡ | 78 (47.0) | 102 (61.4) | 107 (64.5) | 88 (53.0) | 88 (72.7) | 121 |

| TNF-naïve§ | 56 (43.1) | 73 (56.2) | 81 (62.3) | 70 (53.8) | 70 (73.7) | 95 |

| TNF-experienced¶ | 22 (61.1) | 29 (80.6) | 26 (72.2) | 18 (50.0) | 18 (69.2) | 26 |

| PASI90, n (%)‡ | 35 (21.1) | 69 (41.6) | 76 (45.8) | 73 (44.0) | 73 (60.3) | 121 |

| TNF-naïve§ | 25 (19.2) | 48 (36.9) | 59 (45.4) | 59 (45.4) | 59 (62.1) | 95 |

| TNF-experienced¶ | 10 (27.8) | 21 (58.3) | 17 (47.2) | 14 (38.9) | 14 (53.8) | 26 |

| PASI100, n (%)‡ | 20 (12.0) | 37 (22.3) | 57 (34.3) | 55 (33.1) | 55 (45.5) | 121 |

| MDA, n (%) | 70 (25.6) | 95 (34.8) | 106 (38.8) | 112 (41.0) | 112 (51.6) | 217 |

| ΔBL DAS28(CRP) | −1.6 (1.2) | −1.9 (1.3) | −2.1 (1.3) | −2.2 (1.4) | −2.4 (1.3) | 218 |

| DAS28(CRP) <2.6, n (%) | 77 (28.2) | 114 (41.8) | 120 (44.0) | 135 (49.5) | 135 (61.9) | 218 |

| DAS28(CRP) ≤3.2, n (%) | 125 (45.8) | 154 (56.4) | 162 (59.3) | 161 (59.0) | 161 (73.9) | 218 |

| ΔBL LEI** | −1.8 (1.8) | −1.9 (1.8) | −2.0 (1.8) | −2.0 (1.9) | −2.2 (1.8) | 131 |

| ΔBL LDI†† | −38.2 (56.2) | −47.3 (55.3) | −47.1 (55.0) | −48.6 (55.5) | −48.1 (40.0) | 57 |

| ΔBL mNAPSI‡‡ | −1.1 (2.1) | −1.9 (2.2) | −2.1 (2.3) | −2.4 (2.3) | −2.6 (2.2) | 158 |

| PROs | ||||||

| ΔBL HAQ-DI | −0.4 (0.52) | −0.5 (0.60) | −0.5 (0.61) | −0.5 (0.63) | −0.6 (0.61) | 217 |

| ΔBL pain | −24.7 (26.3) | −28.5 (27.2) | −30.6 (28.3) | −31.3 (29.9) | −35.5 (28.5) | 217 |

| ΔBL fatigue | −1.7 (2.2) | −2.0 (2.5) | −2.2 (2.5) | −2.4 (2.5) | −2.7 (2.4) | 208 |

| ΔBL PsAQoL | −3.2 (4.8) | −3.9 (5.1) | −4.2 (5.2) | −4.5 (5.4) | −5.0 (5.4) | 215 |

| ΔBL SF-36 PCS | 7.1 (8.4) | 8.0 (9.1) | 8.5 (9.2) | 9.0 (10.0) | 10.0 (9.9) | 213 |

| ΔBL SF-36 MCS | 3.7 (9.5) | 4.5 (10.0) | 4.0 (10.1) | 3.9 (11.3) | 4.9 (11.0) | 213 |

Data are shown for the Randomised Set. Data were imputed using NRI for missing categorical data and LOCF for missing continuous measures, except for DAS28(CRP) <2.6 or ≤3.2 for which LOCF was used. Data are shown as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified.

*TNF-naïve patients, n=219.

†TNF experienced patients, n=54.

‡PASI data presented for patients with baseline BSA≥3% (n=166).

§TNF-naïve patients with BSA≥3%, n=130.

¶TNF experienced patients with BSA≥3%, n=36.

**LEI reported for patients with enthesitis at baseline (n=172).

††LDI reported for patients with ≥1 dactylitic digit with a circumference ≥10% larger compared with the contralateral digit (n=73).

‡‡mNAPSI reported for patients with nail involvement at baseline (n=197).

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; BL, baseline; BSA, body surface area; CRP, C reactive protein; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DAS, Disease Activity Score; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; LDI, Leeds Dactylitis Index; LEI, Leeds Enthesitis Index; LOCF, carrying forward the last observation; MCS, mental component summary; MDA, minimal disease activity; mNAPSI: modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; NA, not available; NRI, non-responder imputation; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PCS, physical component summary; PRO, patient-reported outcome; PsAQoL, psoriatic arthritis quality of life; Q2W, every 2 weeks; SF-36, short-form 36-item; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Patients originally randomised to placebo who were re-randomised to CZP treatment at week 16 or 24 saw improvements in ACR20 response rates following CZP treatment (figure 2B).

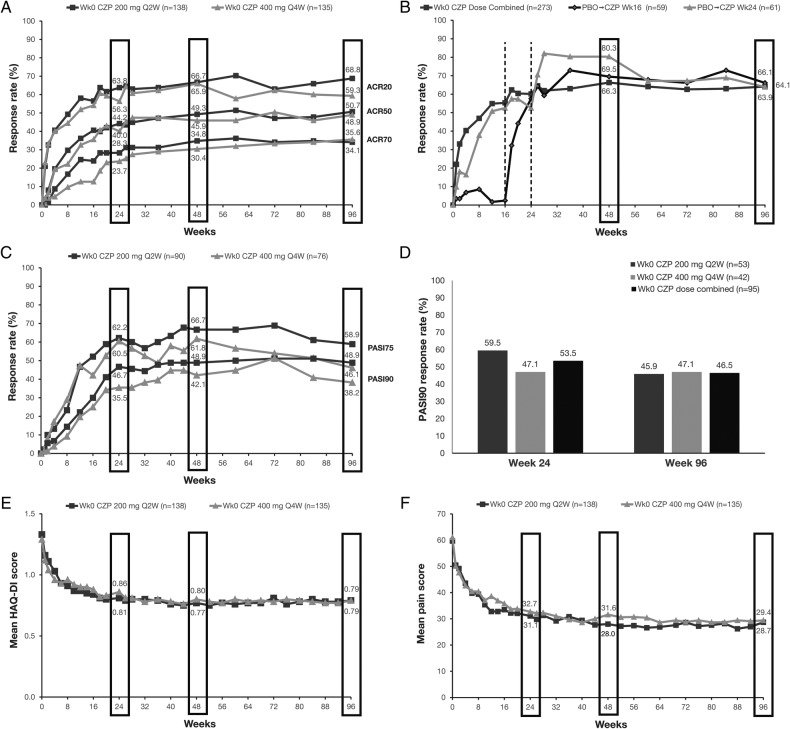

ACR responses were similar between patients with and without prior anti-TNF exposure (table 3). Improvements in ACR20 response and HAQ-DI were similar regardless of whether patients had discontinued prior anti-TNF treatment due to loss of efficacy or other reasons (figure 3).

Figure 3.

ACR20 response rate (A and B) or mean change from baseline in HAQ-DI (C and D) in patients who discontinued prior anti-TNF treatment due to: (A and C) lack of efficacy; (B and D) tolerability or other reasons. Data shown for patients from the Randomised Set of patients from RAPID-PsA with prior anti-TNF exposure. Missing categorical data were imputed by non-responder imputation; missing continuous measures were imputed by the last observation carried forward. ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CZP, certolizumab pegol; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; wk, week.

Improvements observed to week 24 were maintained to week 96 in all PROs measured, including pain, fatigue, HAQ-DI and SF-36 component summaries (table 3).

For patients with ≥3% BSA psoriasis at baseline, improvements in PASI75 and PASI90 response rates seen over 24 weeks were maintained to week 96 (figure 2C) and were similar in patients with and without prior anti-TNF exposure (table 3). Furthermore, 33.1% of patients achieved a PASI100 response at week 96 (combined CZP doses, table 3). Absolute PASI scores were also maintained between weeks 48 and 96, with a mean (±SD) PASI score of 2.6±7.0 at week 48 and 2.6±6.6 at week 96 for combined CZP doses.

Greater improvements in PASI75 response rates were observed for patients with baseline PASI ≥10 (81% and 74% achieved PASI75 at week 24, 78% and 77% at week 48, and 65% and 59% at week 96 for CZP 200 mg Q2W (n=37) and CZP 400 mg Q4W (n=34), respectively) compared to patients with baseline PASI <10 (49% and 50% achieved PASI75 at week 24, 59% and 50% at week 48, and 55% and 36% at week 96 for CZP 200 mg Q2W (n=53) and CZP 400 mg Q4W (n=42), respectively). Greater improvements were also seen in PASI90 and PASI100 (figure 2D and appendix).

For patients with dactylitis, enthesitis or nail involvement at baseline, improvements observed to week 24 in LDI, LEI or modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (mNAPSI), respectively, were sustained to week 96 (table 3).

Data from this radiographic reading campaign indicated that there was no clinically relevant change in radiographic progression in patients treated with CZP to week 96, as measured by change from baseline in mTSS (0.14 (95% CI −0.04 to 0.33)). Progression was also very low during the CZP treatment period for patients initially randomised to placebo who were reallocated to CZP at either week 16 or 24 (−0.08 (95% CI −0.42 to 0.27); and 0.04 (95% CI −0.30 to 0.38), respectively). Similar radiographic outcomes were seen in patients treated with either CZP dose regimen (table 4A).

Table 4.

Change from study Baseline in mTSS over 96 weeks—MMRM approach

|

(A) For patients originally randomised to CZP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 0 CZP 200 mg Q2W N=138 | Week 0 CZP 400 mg Q4W N=135 | Week 0 CZP dose combined N=273 | |

| Baseline (week 0) | |||

| LS mean (SE) | 14.0 (3.5) | 18.1 (3.6) | 16.1 (2.5) |

| 95% CI | (7.1 to 21.0) | (11.1 to 25.2) | (11.1 to 21.0) |

| Median | 4.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Q1–Q3 | 0.8–14.8 | 1.0–13.0 | 1.0–14.5 |

| Week 24 | |||

| LS mean CFB (SE) | 0.04 (0.06) | 0.14 (0.07) | 0.09 (0.05) |

| 95% CI | (−0.09 to 0.16) | (0.02 to 0.27) | (0.00 to 0.18) |

| Median CFB | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Week 48 | |||

| LS mean CFB (SE) | 0.08 (0.09) | 0.13 (0.09) | 0.11 (0.06) |

| 95% CI | (−0.09 to 0.25) | (−0.04 to 0.30) | (−0.01 to 0.23) |

| Median CFB | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Week 96 | |||

| LS mean CFB (SE) | 0.10 (0.13) | 0.19 (0.14) | 0.14 (0.09) |

| 95% CI | (−0.16 to 0.36) | (−0.08 to 0.46) | (−0.04 to 0.33) |

| Median CFB | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

|

(B) For patients originally randomised to PBO | ||

|---|---|---|

| PBO to CZP at week 16* N=75 |

PBO to CZP at week 24 N=61 |

|

| Actual mTSS prior to initiation of CZP treatment | ||

| LS mean (SE) | 26.3 (4.9) | 16.5 (5.3) |

| 95% CI | (16.7 to 35.9) | (6.0 to 26.9) |

| Median | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| Q1–Q3 | 0.5–29.5 | 0.5–15.0 |

| Change in mTSS during CZP treatment (over 32 or 24 weeks)—week 48 | ||

| LS mean (SE) | 0.07 (0.11) | 0.02 (0.11) |

| 95% CI | (−0.16 to 0.29) | (−0.20 to 0.23) |

| Median change | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Change in mTSS during CZP treatment (over 80 or 72 weeks)—week 96 | ||

| LS mean (SE) | −0.08 (0.17) | 0.04 (0.17) |

| 95% CI | (−0.42 to 0.27) | (−0.30 to 0.38) |

| Median change | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Data are shown for the Randomised Set. LS means and corresponding SEs and 95% CIs are estimated using a mixed model with mTSS as the dependent variable, treatment and visit as fixed-effect factors, treatment by visit as an interaction term, and by specifying an unstructured covariance matrix. Medians are calculated based on the observed values.

*The PBO to CZP at week 16 treatment group also includes participants randomised to PBO withdrawing before having the opportunity to switch to CZP.

CFB, change from baseline; CZP, certolizumab pegol; LS, least squares; MMRM, mixed effect model for repeated measures; mTSS, modified total Sharp score; PBO: Placebo; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

For patients originally randomised to CZP, those with baseline mTSS >3.5 (and therefore at increased risk of further progression) had, on average, a slightly higher radiographic progression to week 96 than patients with baseline mTSS <3.5, though the progression remained remarkably low in both subgroups (mTSS >3.5: 0.24 (95% CI −0.14 to 0.62); and mTSS ≤3.5: 0.07 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.15); table 5). The proportion of patients with mTSS non-progression to week 96 remained high with both cut-off values (mTSS ≤0: 74.3%; mTSS ≤0.5: 87.2%; week 0 CZP-randomised patients, combined doses, observed data; table 6). Similar results were observed for placebo patients re-randomised to CZP (tables 4B, 5B and 6B).

Table 5.

Change from baseline in mTSS at week 96 by baseline subgroups—MMRM approach

|

(A) For patients originally randomised to CZP | ||

|---|---|---|

| Week 0 CZP dose combined LS mean (SE) (95% CI) |

||

| Study Baseline (week 0) | Week 96 | |

| Baseline mTSS ≤3.5 (N=138) | ||

| Actual mTSS | 1.2 (0.1) (1.0 to 1.4) |

1.2 (0.1) (1.0 to 1.4) |

| CFB in mTSS | – | 0.07 (0.04) (0.00 to 0.15) |

| Baseline mTSS >3.5 (N=131) | ||

| Actual mTSS | 32.1 (4.7) (22.8 to 41.4) |

32.4 (4.7) (23.1 to 41.7) |

| CFB in mTSS | – | 0.24 (0.19) (−0.14 to 0.62) |

|

(B) For patients originally randomised to PBO | ||

|---|---|---|

| PBO to CZP at week 16 LS mean (SE) (95% CI) |

PBO to CZP at week 24 LS mean (SE) (95% CI) |

|

| Baseline mTSS ≤3.5 | ||

| Number of patients | 37 | 29 |

| Actual mTSS prior to initiation of CZP treatment | 1.1 (0.2) (0.7 to 1.5) |

0.9 (0.2) (0.5 to 1.3) |

| Change in mTSS during CZP treatment (over 80 or 72 weeks) | 0.14 (0.05) (0.03 to 0.24) |

−0.03 (0.06) (−0.14 to 0.08) |

| Baseline mTSS >3.5 | ||

| Number of patients | 35 | 30 |

| Actual mTSS prior to initiation of CZP treatment | 53.0 (9.1) (35.0 to 71.0) |

32.1 (9.9) (12.7 to 51.5) |

| Change in mTSS during CZP treatment (over 80 or 72 weeks) | −0.31 (0.37) (−1.03 to 0.42) |

0.11 (0.35) (−0.58 to 0.81) |

Data are shown for the randomised set. LS means and corresponding SEs and 95% CIs are estimated using a mixed model with mTSS as the dependent variable, treatment and visit as fixed-effect factors, treatment by visit as an interaction term, and by specifying an unstructured covariance matrix. Medians are calculated based on the observed values.

CFB, change from baseline; CZP, certolizumab pegol; LS, least squares; MMRM, mixed effect model for repeated measures; mTSS, modified total Sharp score; PBO, placebo; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

Table 6.

Rate of mTSS non-progression at week 96—observed case

| (A) For patients originally randomised to CZP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 0 CZP 200 mg Q2W N=138 | Week 0 CZP 400 mg Q4W N=135 | Week 0 CZP dose combined N=273 | |

| Assessed for progression, n | 112 | 106 | 218 |

| Rate of non-progression at week 96 (change from Baseline in mTSS ≤0.5) | |||

| Non-progressors, n (%)* | 98 (87.5) | 92 (86.8) | 190 (87.2) |

| Rate of non-progression at week 96 (change from Baseline in mTSS ≤0) | |||

| Non-progressors, n (%)* | 82 (73.2) | 80 (75.5) | 162 (74.3) |

| (B) For patients originally randomised to PBO (after 80 or 72 weeks of CZP treatment for PBO patients switching at weeks 16 and 24, respectively) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PBO to CZP at week 16† N=59 |

PBO to CZP at week 24† N=61 |

PBO to CZP† N=120 |

|

| Assessed for progression, n | 51 | 53 | 104 |

| Rate of non-progression over 80 or 72 weeks (change from CZP Baseline in mTSS ≤0.5)—week 96 | |||

| Non-progressors, n (%)* | 48 (94.1) | 50 (94.3) | 98 (94.2) |

| Rate of non-progression over 80 or 72 weeks (change from CZP Baseline in mTSS ≤0)—week 96 | |||

| Non-progressors, n (%)* | 39 (76.5) | 47 (88.7) | 86 (82.7) |

Data are shown for the Randomised Set.

*Percentage is based on the number of participants assessed for progression at the visit.

†PBO patients who withdrew prior to switching to CZP were not considered.

CZP, certolizumab pegol; mTSS, modified total Sharp score; PBO, placebo; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

Safety

The safety set consisted of 393 patients who received at least one dose of CZP at any stage of the 96-week trial period. Total exposure to week 96 was 606 PY. During this period, AEs occurred in 345 patients (87.8%; ER per 100 PY=329.8), the majority of which were considered by the investigator to be mild or moderate in nature (table 7). Serious AEs (SAEs) occurred in 67 patients (17.0%; ER=14.5/100 PY), with the highest number reported for the Infection and Infestations System Organ Class. Of the 16 infections considered serious (4.1%; ER=3.3/100 PY), there were no cases of active tuberculosis. The most common serious infections were pneumonia, HIV, erysipelas and urinary tract infections, of which there were two cases reported for each (0.5%; ER=0.3/100 PY). During the 96-week trial period, 36 patients experienced an AE leading to withdrawal (9.2%; table 7).

Table 7.

TEAEs during 96 weeks of the RAPID-PsA trial

| CZP 200 mg Q2W N=198 n (%) [ER] |

CZP 400 mg Q4W N=195 n (%) [ER] |

All CZP N=393 n (%) [ER] |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 175 (88.4) [339.2] | 170 (87.2) [320.0] | 345 (87.8) [329.8] |

| TEAEs by intensity* | |||

| Mild | 151 (76.3) | 148 (75.9) | 299 (76.1) |

| Moderate | 113 (57.1) | 103 (52.8) | 216 (55.0) |

| Severe | 23 (11.6) | 22 (11.3) | 45 (11.5) |

| Drug-related TEAEs | 82 (41.4) | 86 (44.1) | 168 (42.7) |

| Infections† | 125 (63.1) [95.6] | 113 (57.9) [96.9] | 238 (60.6) [96.2] |

| Upper respiratory infections‡ | 25 (12.6) [13.7] | 31 (15.9) [13.7] | 56 (14.2) [13.7] |

| Serious infections | 7 (3.5) [2.6] | 9 (4.6) [4.0] | 16 (4.1) [3.3] |

| Serious TEAEs | 31 (15.7) [13.4] | 36 (18.5) [15.7] | 67 (17.0) [14.5] |

| Death | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | 6 (1.5) |

| Withdrawal due to TEAEs§ | 22 (11.1) | 14 (7.2) | 36 (9.2) |

| Cardiac disorders | 4 (2.0) | 0 | 4 (1.0) |

| Eye disorders | 2 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (0.5) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) |

| Infections and infestations | 6 (3.0) | 6 (3.1) | 12 (3.1) |

| Investigations | 4 (2.0) | 1 (0.5) | 5 (1.3) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (0.8) |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified, including cysts and polyps | 1 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) |

| Nervous system disorders | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.3) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 5 (2.5) | 0 | 5 (1.3) |

Data shown for the Safety Set of all patients who received at least one dose of CZP at any stage of the 96-week trial period.

*As determined by the investigator.

†System Organ Class.

‡Preferred Term; ER per 100 patient-years.

§A patient could have more than one discontinuation reason.

CZP, certolizumab pegol; ER, event rate; Q2W, every 2 weeks; TEAE, treatment emergent adverse event.

Four malignancies (1.0%; ER=0.7/100 PY) were reported during the 96-week (double-blind, dose-blind and OLE) treatment period of this trial including two cases of breast cancer, one case of lymphoma and one previously reported in situ stage 0 cervix carcinoma in the double-blind treatment period occurring after 8 days of CZP treatment.5

During the 96-week trial period, six patients experienced an AE leading to death, three of which were previously reported: one myocardial infarction, one sudden death5 and one breast cancer;13 and three of which occurred between weeks 48 and 96, including one cardiac arrest, one case of infection (sepsis) and one lymphoma. Both cardiac events were considered unrelated to study medication by the investigator.

Discussion

Results from the RAPID-PsA trial demonstrate that the efficacy of CZP in treating the signs and symptoms of PsA was sustained over 96 weeks. Furthermore, efficacy was maintained in patients with prior anti-TNF exposure, an important finding given the fact that patients with PsA frequently cycle between different anti-TNF treatments14 and that other biologicals have not shown such strong efficacy as a secondary biological treatment.15 Efficacy was also demonstrated in these patients whether or not they withdrew from their prior anti-TNF treatment due to a lack of efficacy.

Maintenance of improvements was observed across a broad range of disease manifestations including dactylitis, enthesitis, cutaneous manifestations and peripheral arthritis. The improvements in skin measures are particularly important for patients’ quality of life, given the finding that patients with PsA who also suffer from psoriatic skin involvement (60.8% of the week 0 CZP-randomised RAPID-PsA patient population had ≥3% BSA psoriasis at baseline) have a greater HRQoL burden than patients with PsA without skin involvement.4

Furthermore, analysis of X-ray data did not reveal any clinically relevant progression of structural damage, as measured by mTSS, over 96 weeks of CZP exposure. Similar results were observed with both CZP dose regimens and for the CZP treatment period in patients originally randomised to placebo who later switched to CZP.

MMRM was selected as the method for analysing the week 96 mTSS data presented here. The use of MMRM relies on the assumption that patients who drop out prior to week 96 would have outcomes similar to other patients in the same treatment group had they continued in the study.16 In a previous report of mTSS data based on the 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of RAPID-PsA, different methods for imputation of missing data were considered.6 The methods used in that report were appropriate given the context of a placebo-controlled comparison at an early time point with relatively few missing data points. However, MMRM was deemed preferable for this long-term (96-week) analysis of radiographic progression for patients on CZP as it is a model-based approach which utilises all available data, even for those patients with missing data at one or more visits.

The safety profile of CZP was similar to previous reports of CZP in PsA, axSpA and RA, and no new safety signals were reported. The most frequent AEs were infections (ER=96.2/100 PY), of which the most common was upper respiratory tract infection (ER=13.7/100 PY).

Previous trials of anti-TNF agents have addressed the problem of missing efficacy data using a variety of approaches. While NRI may provide a conservative estimate of long-term treatment efficacy, presenting observed data alongside this can be informative, since it provides information based solely on those patients remaining on treatment.18 In this publication, we therefore present both observed and imputed data in the intention-to-treat population, which is considered to give a more representational perspective on real-life clinical practice.18 19 The maintenance of improvements with CZP treatment to week 96 of RAPID-PsA was demonstrated using both methodologies.

Both the CZP 200 mg Q2W and CZP 400 mg Q4W dosing regimens were shown to provide maintained efficacy, providing flexibility in dosing options available to patients who respond to CZP therapy.

In conclusion, the improvements in clinical and patient-reported outcomes, which were observed over 24 weeks of the RAPID-PsA trial in both CZP dosing regimens, were maintained throughout the dose-blind trial period to week 48 and the OLE to week 96. The maintenance of improvements was observed in patients regardless of prior anti-TNF exposure. Skin outcomes were also maintained to week 96 and improvements were particularly strong in patients with severe skin involvement at baseline. This study also demonstrated the prevention of any clinically relevant change in structural damage, as measured by mTSS, for patients treated with CZP, in line with reported findings from trials of other anti-TNFs in PsA.20–23 The safety profile of CZP in PsA over 96 weeks was consistent with that observed during 24 weeks, with no new safety signals reported.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the patients, the investigators and their teams who took part in this study; they also acknowledge Marine Champsaur (previously of UCB Pharma, Belgium) and Owen Davies (UCB Pharma, UK) for their critical review, Tommi Nurminen (UCB Pharma, Germany) for assistance with mTSS analyses and Oana Purcaru (UCB Pharma, Belgium) for the critical review and contribution to the mTSS analyses, and Costello Medical Consulting, UK, for their writing and editorial assistance, which was funded by UCB Pharma.

Appendix.

Long-term efficacy outcomes to week 96 of the RAPID-PsA trial for patients originally randomised to CZP

| Mean value (SD) or n (%) of patients | Week 0 CZP 200 mg Q2W (n=138) | Week 0 CZP 400 mg Q4W (n=135) | Week 0 CZP dose combined (n=273) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| MDA, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) |

| DAS28(CRP), mean (SD) | 5.0 (1.0) | 5.0 (1.0) | 5.0 (1.0) |

| DAS28(CRP) <2.6, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) |

| DAS28(CRP) ≤3.2, n (%) | 4 (2.9) | 3 (2.2) | 7 (2.6) |

| LEI, mean (SD)* | 3.1 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.6) | 3.0 (1.6) |

| LDI, mean (SD)† | 45.3 (36.0) | 56.8 (75.9) | 51.3 (60.0) |

| mNAPSI, mean (SD)‡ | 3.1 (1.8) | 3.4 (2.2) | 3.3 (2.0) |

| Week 48 | |||

| ACR20, n (%) (NRI) | 92 (66.7) | 89 (65.9) | 181 (66.3) |

| TNF-naïve§ | 74 (69.2) | 74 (66.1) | 148 (67.6) |

| TNF-experienced¶ | 18 (58.1) | 15 (65.2) | 33 (61.1) |

| ACR50, n (%) (NRI) | 68 (49.3) | 62 (45.9) | 130 (47.6) |

| TNF-naïve§ | 54 (50.5) | 50 (44.6) | 104 (47.5) |

| TNF-experienced¶ | 14 (45.2) | 12 (52.2) | 26 (48.1) |

| ACR70, n (%) (NRI) | 48 (34.8) | 41 (30.4) | 89 (32.6) |

| TNF-naïve§ | 38 (35.5) | 33 (29.5) | 71 (32.4) |

| TNF-experienced¶ | 10 (32.3) | 8 (34.8) | 18 (33.3) |

| PASI75, n (%)** (NRI) | 60 (66.7) | 47 (61.8) | 107 (64.5) |

| PASI≥10†† | 29 (78.4) | 26 (76.5) | 55 (77.5) |

| PASI<10‡‡ | 31 (58.5) | 21 (50.0) | 52 (54.7) |

| PASI90, n (%)** (NRI) | 44 (48.9) | 32 (42.1) | 76 (45.8) |

| PASI≥10†† | 21 (56.8) | 17 (50.0) | 38 (53.5) |

| PASI<10‡‡ | 23 (43.4) | 15 (35.7) | 38 (40.0) |

| PASI100, n (%)** (NRI) | 36 (40.0) | 21 (27.6) | 57 (34.3) |

| PASI≥10†† | 17 (45.9) | 10 (29.4) | 27 (38.0) |

| PASI<10‡‡ | 19 (35.8) | 11 (26.2) | 30 (31.6) |

| MDA, n (%) (NRI) | 55 (39.9) | 57 (37.8) | 106 (38.8) |

| DAS28(CRP), mean (SD) (LOCF) | 2.9 (1.3) | 3.1 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.3) |

| ΔBL DAS28(CRP), mean (SD) (LOCF) | −2.2 (1.3) | −2.0 (1.3) | −2.1 (1.3) |

| DAS28(CRP) <2.6, n (%) (LOCF) | 66 (47.8) | 54 (40.0) | 120 (44.0) |

| DAS28(CRP) ≤3.2, n (%) (LOCF) | 83 (60.1) | 79 (58.5) | 162 (59.3) |

| LEI, mean (SD)* (LOCF) | 1.0 (1.7) | 0.9 (1.6) | 0.9 (1.7) |

| ΔBL LEI, mean (SD)* (LOCF) | −2.1 (1.8) | −2.0 (1.8) | −2.0 (1.8) |

| LDI, mean (SD)† (LOCF) | 5.6 (17.0) | 2.9 (11.3) | 4.2 (14.3) |

| ΔBL LDI, mean (SD)† (LOCF) | −39.7 (33.1) | −53.9 (69.1) | −47.1 (55.0) |

| mNAPSI, mean (SD)‡ | 1.2 (1.8) | 1.1 (1.7) | 1.1 (1.7) |

| ΔBL mNAPSI, mean (SD)‡ (LOCF) | −1.9 (2.3) | −2.4 (2.3) | −2.1 (2.3) |

| Week 96 | |||

| ACR20, n (%) (NRI) | 95 (68.8) | 80 (59.3) | 175 (64.1) |

| TNF-naïve§ | 73 (68.2) | 68 (60.7) | 141 (64.4) |

| TNF-experienced¶ | 22 (71.0) | 12 (52.2) | 34 (63.0) |

| ACR50, n (%) (NRI) | 70 (50.7) | 66 (48.9) | 136 (49.8) |

| TNF-naïve§ | 54 (50.5) | 55 (49.1) | 109 (49.8) |

| TNF-experienced¶ | 16 (51.6) | 11 (47.8) | 27 (50.0) |

| ACR70, n (%) (NRI) | 47 (34.1) | 48 (35.6) | 95 (34.8) |

| TNF-naïve§ | 35 (32.7) | 42 (37.5) | 77 (35.2) |

| TNF-experienced¶ | 12 (38.7) | 6 (26.1) | 18 (33.3) |

| PASI75, n (%)** (NRI) | 53 (58.9) | 35 (46.1) | 88 (53.0) |

| PASI≥10†† | 24 (64.9) | 20 (58.8) | 44 (62.0) |

| PASI<10‡‡ | 29 (54.7) | 15 (35.7) | 44 (46.3) |

| PASI90, n (%)** (NRI) | 44 (48.9) | 29 (38.2) | 73 (44.0) |

| PASI≥10†† | 17 (45.9) | 16 (47.1) | 33 (46.5) |

| PASI<10‡‡ | 27 (50.9) | 13 (31.0) | 40 (42.1) |

| PASI100, n (%)** (NRI) | 33 (36.7) | 22 (28.9) | 55 (33.1) |

| PASI≥10†† | 9 (24.3) | 10 (29.4) | 19 (26.8) |

| PASI<10‡‡ | 24 (45.3) | 12 (28.6) | 36 (37.9) |

| MDA, n (%) (NRI) | 55 (39.9) | 57 (42.2) | 112 (41.0) |

| DAS28(CRP), mean (SD) (LOCF) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.9 (1.4) | 2.8 (1.4) |

| ΔBL DAS28(CRP), mean (SD) (LOCF) | −2.2 (1.4) | −2.1 (1.3) | −2.2 (1.4) |

| DAS28(CRP) <2.6, n (%) (LOCF) | 66 (47.8) | 69 (51.1) | 135 (49.5) |

| DAS28(CRP) ≤3.2, n (%) (LOCF) | 82 (59.4) | 79 (58.5) | 161 (59.0) |

| LEI, mean (SD)* (LOCF) | 1.1 (1.8) | 0.8 (1.5) | 1.0 (1.7) |

| ΔBL LEI, mean (SD)* (LOCF) | −1.9 (1.8) | −2.1 (1.9) | −2.0 (1.9) |

| LDI, mean (SD)† (LOCF) | 2.4 (11.1) | 2.9 (11.3) | 2.7 (11.1) |

| ΔBL LDI, mean (SD)† (LOCF) | −42.9 (35.5) | −53.9 (69.1) | −48.6 (55.5) |

| mNAPSI, mean (SD)‡ (LOCF) | 0.9 (1.6) | 0.9 (1.4) | 0.9 (1.5) |

| ΔBL mNAPSI, mean (SD)‡ (LOCF) | −2.2 (2.3) | −2.6 (2.3) | −2.4 (2.3) |

Data shown are for the Randomised Set. Non-responder imputation was used for dichotomous outcomes and the last observation carried forward was used for continuous outcomes.

*The numbers of patients with enthesitis at baseline in CZP 200 mg Q2W, CZP 400 mg Q4W and CZP doses combined groups were 88, 84 and 172, respectively.

†The numbers of patients with dactylitis at baseline in CZP 200 mg Q2W, CZP 400 mg Q4W and CZP doses combined groups were 35, 38 and 73, respectively.

‡The numbers of patients with nail disease at baseline in CZP 200 mg Q2W, CZP 400 mg Q4W and CZP doses combined groups were 92, 105 and 197, respectively.

§The numbers of patients without prior anti-TNF exposure in CZP 200 mg Q2W, CZP 400 mg Q4W and CZP doses combined groups were 107, 112 and 219, respectively.

¶The numbers of patients with prior anti-TNF exposure in CZP 200 mg Q2W, CZP 400 mg Q4W and CZP doses combined groups were 31, 23 and 54, respectively.

**The numbers of patients with baseline psoriasis BSA≥3% in CZP 200 mg Q2W, CZP 400 mg Q4W and CZP doses combined groups were 90, 76 and 166, respectively.

††The numbers of patients with psoriasis BSA≥3% and PASI score ≥10 at baseline in CZP 200 mg Q2W, CZP 400 mg Q4W and CZP doses combined groups were 37, 34 and 71, respectively.

‡‡The numbers of patients with psoriasis BSA≥3% and PASI score <10 at baseline in CZP 200 mg Q2W, CZP 400 mg Q4W and CZP doses combined groups were 53, 42 and 95, respectively.

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; BL, baseline; BSA, body surface area; CRP, C reactive protein; CZP, certolizumab pegol; DAS, Disease Activity Score; LDI, Leeds Dactylitis Index; LEI, Leeds Enthesitis Index; LOCF, carrying forward the last observation; MDA, minimal disease activity; NRI, non-responder imputation; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; Q2W, every 2 weeks; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in the acquisition and interpretation of data from the RAPID-PsA study and also critically reviewed each draft of the manuscript before approving the final version.

Funding: UCB Pharma sponsored the study and the development of the manuscript. In addition to content approval by the authors, UCB signed off on the manuscript following a full review to ensure that the publication did not contain any information which has the potential to damage the intellectual property of UCB.

Competing interests: PM has received grant/research support and/or consultant fees and/or speaker's bureau fees from (Abbott) AbbVie, Amgen, BiogenIdec, BMS, Celgene, Crescendo, Genentech, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma and Vertex. AD has received grant/research support and/or consultant fees from Abbott, Amgen, Janssen, Novartis and UCB Pharma. RF has received grant/research support and/or consultant fees from Abbott, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, BiogenIdec, BMS, Genetech Inc, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis and UCB Pharma. JW has received consultant fees and grants from UCB Pharma. DG has received consultation fees and/or research grants from Abbott, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Johnson & Johnson, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma. PL has received consultant fees from Roche. AT has received grant/research support and/or consultant fees and/or speaker fees from Abbive, Amgen, Celgene, Genentech-Roche, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma. MK has received grants from Abbott, Amgen and Pfizer. OF has received grants from Abbvie, BMS, MSD, Pfizer and Roche and been involved in Clinical Trials for Abbvie, BMS, Lilly, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB Pharma; and Ad boards for Abbvie, Celgene, Janssen, Roche and UCB Pharma; and Speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Celgene, Janssen, Pfizer and UCB Pharma. RL has received grant/research support and/or consultant fees and/or speaker's bureau fees from Abbott, Ablynx, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Centocor, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Novartis, Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Schering-Plough, UCB Pharma and Wyeth. M. de Longueville, BH and LP are employees of UCB Pharma. DvdH has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Augurex, BMS, Celgene, Centocor, Chugai, Covagen, Daiichi, Eli-Lilly, GSK, Janssen Biologics, Merck, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, UCB Pharma and Vertex; and is the Director of Imaging Rheumatology bv.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lee S, Mendelsohn A, Sarnes E. The burden of psoriatic arthritis: a literature review from a global health systems perspective. P T 2010;35:680–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers WA, Gottlieb AB, Mease P. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: clinical features and disease mechanisms. Clin Dermatol 2006;24:438–47. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mease PJ, Menter MA. Quality-of-life issues in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: outcome measures and therapies from a dermatological perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:685–704. 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mease PJ, van Tubergen A, Deodhar A et al. Comparing health-related quality of life across rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: analyses from certolizumab pegol clinical trial baseline data. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:766 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.2269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mease PJ, Fleischmann R, Deodhar A et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a phase 3 double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study (RAPID-PsA). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:48–55. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Heijde D, Fleischmann R, Wollenhaupt J et al. Effect of different imputation approaches on the evaluation of radiographic progression in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results of the RAPID-PsA 24-week phase III double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study of certolizumab pegol. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:233–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gladman D, Fleischmann R, Coteur G et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on multiple facets of psoriatic arthritis as reported by patients: 24-week patient-reported outcome results of a phase III, multicenter study. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1085–92. 10.1002/acr.22256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P et al. Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73. 10.1002/art.21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:48–53. 10.1136/ard.2008.102053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mease PJ. Measures of psoriatic arthritis: Tender and Swollen Joint Assessment, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI), Modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (mNAPSI), Mander/Newcastle Enthesitis Index (MEI), Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI), Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC), Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesis Score (MASES), Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI), Patient Global for Psoriatic Arthritis, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Psoriatic Arthritis Quality of Life (PsAQOL), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC), Psoriatic Arthritis Joint Activity Index (PsAJAI), Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA), and Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index (CPDAI). Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:S64–85. 10.1002/acr.20577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Heijde D, Sharp J, Wassenberg S et al. Psoriatic arthritis imaging: a review of scoring methods. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:ii61–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smolen JS, Emery P, Ferraccioli GF et al. Certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis patients with low to moderate activity: the CERTAIN double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:843–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mease P, Fleischmann R, Wollenhaupt J et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol over 48 weeks on signs and symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis with and without prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor exposure. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:S132–3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glintborg B, Østergaard M, Krogh NS et al. Clinical response, drug survival, and predictors thereof among 548 patients with psoriatic arthritis who switched tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor therapy: results from the Danish Nationwide DANBIO Registry. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1213–23. 10.1002/art.37876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritchlin C, McInnes I, Kavanaugh A et al. Maintenance of efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite prior conventional nonbiologic and anti-TNF biologic therapy: 1 yr results of the PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:A48–A. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaVange LM. The role of statistics in regulatory decision making. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2014;48:10–19. 10.1177/2168479013514418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gladman D, Fleischmann R, Coteur G et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on multiple facets of psoriatic arthritis as reported by patients: 24-week patient-reported outcome results of a phase III, multicenter study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:1085–92. 10.1002/acr.22256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papp KA, Fonjallaz P, Casset-Semanaz F et al. Analytical approaches to reporting long-term clinical trial data. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2001–8. 10.1185/03007990802215315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ 1999;319:670–4. 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kavanaugh A, Antoni CE, Gladman D et al. The infliximab multinational psoriatic arthritis controlled trial (IMPACT): results of radiographic analyses after 1 year. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1038–43. 10.1136/ard.2005.045658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mease PJ, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX et al. Continued inhibition of radiographic progression in patients with psoriatic arthritis following 2 years of treatment with etanercept. J Rheumatol 2006;33:712–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kavanaugh A, van der Heijde D, McInnes IB et al. Golimumab in psoriatic arthritis: one-year clinical efficacy, radiographic, and safety results from a phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2504–17. 10.1002/art.34436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Ritchlin CT et al. Adalimumab for long-term treatment of psoriatic arthritis: Forty-eight week data from the adalimumab effectiveness in psoriatic arthritis trial. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:476–88. 10.1002/art.22379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]