Abstract

We present a case of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in an otherwise healthy 18-year-old man who presented with melena. Endoscopy revealed an ulcerated mass in the stomach and pathology confirmed this to be a malignant, poorly differentiated choriocarcinoma. Further imaging showed a left testicular mass with evidence of pulmonary, gastric, and brain metastases, and blood tests revealed an hCG level of 32,219 U/L. He was diagnosed with advanced metastatic testicular choriocarcinoma and underwent intensive induction chemotherapy and an orchidectomy. Metastatic testicular choriocarcinoma is a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Introduction

Pure testicular choriocarcinoma comprises less than 1% of all germ cell tumors.1 Choriocarcinomas metastasize early, with around half of patients having evidence of metastatic disease at first presentation2; however, less than 5% of patients have gastrointestinal (GI) involvement.3 Such patients may present with upper GI bleeding secondary to metastatic deposits in the gastric mucosa, or to nodal metastases eroding into the duodenum.

Case Report

An 18-year-old man was admitted with a 5-day history of black stools, lethargy, and dizziness. Blood pressure was 130/58 mm Hg and heart rate was 98 bpm. He was pale with no evidence of lymphadenopathy; chest was clear and abdomen was soft and non-tender with no organomegaly. Rectal examination revealed no evidence of bleeding or melena.

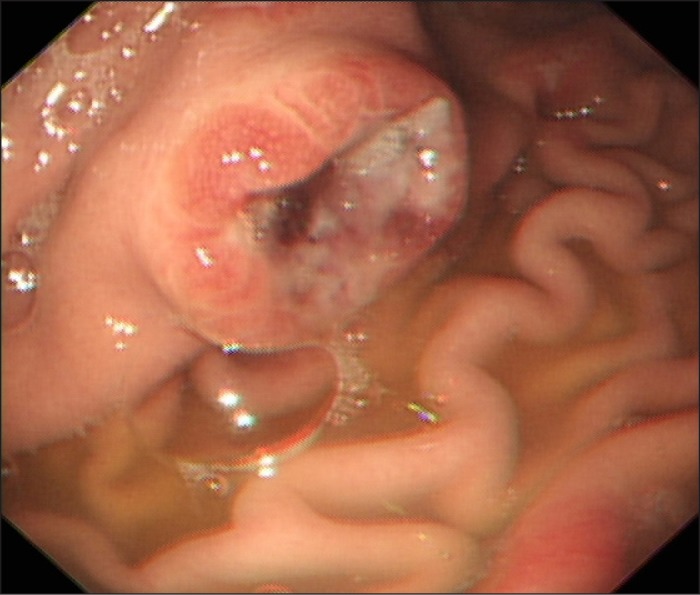

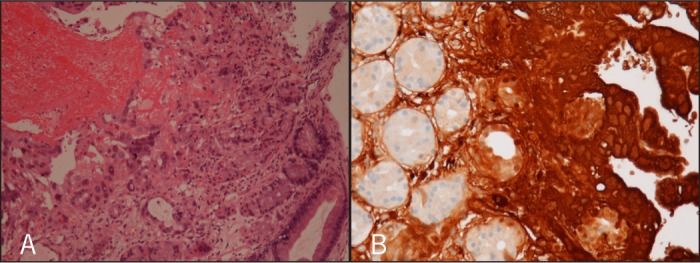

He had no significant past medical or family history. He took no regular medications and had no known drug allergies. He smoked 10 cigarettes a day, 3-4 g of cannabis per week, and was an occasional binge drinker. Admission laboratory values revealed a severe microcytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 4.7 g/dL. Following fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion, upper GI endoscopy revealed a 1.5-cm ulcerated mass on the lower body of the greater curve of the stomach (Figure 1). Biopsies revealed a poorly differentiated choriocarcinoma (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

A 1.5-cm ulcerated mass on the lower body of the greater curve of the stomach.

Figure 2.

(A) Biopsy revealed extensive hemorrhage and infiltration of gastric mucosa by trophoblastic epithelium, including syncitiotrophoblast consistent with metastatic choriocarcinoma. (B) Imunohistochemistry for human chorionic gonadotropin revealed intense (brown) positivity within tumor cells, while gastric glands remained negative, confirming the diagnosis.

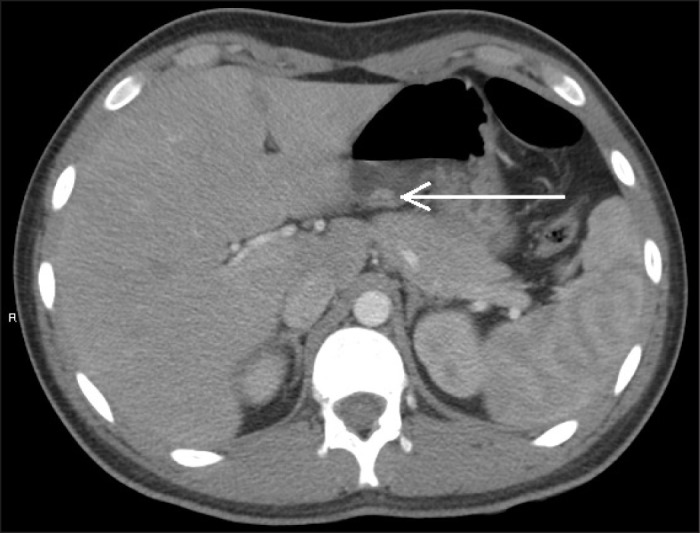

A computed tomography (CT) scan of his brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed multiple pulmonary nodules, low-volume left para-aortic lymphadenopathy, a vascular left testicular mass, a small enhancing lesion in the left parietal lobe, and a 1.2-cm mucosal-based lesion lying posteriorly within the gastric antrum (Figure 3). Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level was 32,219 U/L (normal: 1–5 U/L), in keeping with a diagnosis of choriocarcinoma. Testicular ultrasound confirmed a left testicular mass. The patient was diagnosed with advanced testicular choriocarcinoma, and given the presence of non-pulmonary visceral metastases, he was classified in a poor prognostic group with a 5-year survival of 48%, in keeping with the International Germ Cell Consensus (IGCC) classification system.4

Figure 3.

Abdominal CT showing 1.2-cm mucosal-based lesion lying posteriorly in the gastric antrum.

He was started on an intensive induction chemotherapy regimen consisting of carboplatin, bleomycin, vincristine, and cisplatin, followed by bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (CBOP-BEP). Radiology following completion of chemotherapy showed a reduction in the number and volume of pulmonary metastases and para-aortic lymphadenopathy, resolution of the brain metastasis, and a serum hCG level within normal limits. Following this, the patient failed to attend several appointments, including an orchidectomy. Several months later, his serum hCG level was rising, CT-positron emission tomography (PET) showed a new right adrenal metastasis, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed 5 new brain metastases. He underwent a left orchidectomy and was started on salvage chemotherapy with cisplatin, ifosfamide, and paclitaxel (TIP regimen). Having completed salvage chemotherapy at the time this report, the serum hCG level was within normal limits, and a CT-PET showed no fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity, consistent with response to treatment.

Discussion

Testicular germ cell tumors (GCTs) are rare, accounting for only around 1–2% of all malignancies in males. Pure choriocarcinoma of the testis makes up less than 1% of GCTs, and are most common in men aged 20–30 years.1,5 Choriocarcinoma is most often seen as a component of mixed germ cell tumors in around 8–10% of cases. Unlike other GCTs, choriocarcinomas metastasize early, spreading hematogenously to other sites, most often lung, liver, and brain.6 Half of patients will have metastatic disease at the time of presentation.2 Metastases have been reported in as many as 83% of patients, with most patients having multiple sites of metastases.7 Choriocarcinoma most commonly presents with symptoms secondary to metastases, rather than the primary tumor, which may go unnoticed. Patients can present initially with acute disorders secondary to hemorrhage or necrosis of either the primary lesion, or the metastases. Examples of this include hemoptysis, hematemesis, melena, and epistaxis, as well as hemorrhage into areas such as brain, scrotum, or peritoneum.8

Concentrations of hCG are elevated secondary to an increase in production by the syncytiotrophoblastic component of the tumor. HCG is an important marker, not only for diagnosis of choriocarcinoma, but for grading and monitoring response to treatment. An hCG level >50,000 IU/L puts the patient in the IGCC poor prognostic group.4

GI metastases are an unusual finding, most commonly arising from malignancies of the breast, lung, or metastatic melanoma.9 Fewer than 5% of patients have GI metastases from primary testicular choriocarcinoma.3 The stomach is the most common GI location; however, several case studies have reported lesions in the small intestine and colon.10 It is important to distinguish a primary testicular choriocarcinoma metastasizing to the GI tract from a primary gastric choriocarcinoma.2 Some authors recommend a testicular wedge biopsy, even in cases where a palpable testicular mass or radiologic evidence cannot be found, before labeling it as a primary gastric choriocarcinoma.2 Upper GI bleeding from metastatic disease is a very rare initial manifestation of a testicular carcinoma; however a malignant tumor should always be considered if a gastric ulcer is found.10,11 Endoscopic appearance of metastases can be variable and biopsy of the lesion is critical to determine the origin of the tumor and plan appropriate treatment.12

Disclosures

Author contributions: K. Lowe, J. Paterson, S. Armstrong, and C. Mowat wrote the manuscript. S. Walsh provided and interpreted the pathology images, and wrote the manuscript. M. Groome provided endoscopy images, wrote the manuscript, and is the article guarantor.

Financial disclosure: None to report.

Informed consent was obtained for this case report.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Dr. Alan McCulloch for providing the radiology images for this case report.

References

- 1.Sang-Cheol L, Kyoung HK, Sung HK, et al. Mixed testicular germ cell tumor presenting as metastatic pure choriocarcinoma involving multiple lung metastases that was effectively treated with high-dose chemotherapy. Cancer Res Treat. 2009;41(4):229–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harikumar R, Harish K, Aravindan KP, Thomas V. Testicular choriocarcinoma with gastric metastasis presenting as hematemesis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23(6):223–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson JL, Blute ML. Coffee grounds emesis: Rare presentation of testicular cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Urology. 2004;64(2):376–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. International germ cell consensus classification: A prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(2):594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramón y Cajal S, Piñango L, Barat A, et al. Metastatic pure choriocarcinoma of the testis in an elderly man. J Urol. 1987;137(3):516–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen X, Xu L, Chen X, et al. Testicular choriocarcinoma metastatic to skin and multiple organs: Two case reports and review of literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(4):486–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yokoi K, Tanaka N, Furukawa K, et al. Male choriocarcinoma with metastasis to the jejunum: A case report and review of the literature. J Nippon Med Sch. 2008;75(2):116–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worster A, Sharma S, Mookadam F, Opie J. Acute presentation of choriocarcinoma: A case study and review of the literature. CJEM. 2002;4(2):111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green LK. Hematogenous metastases to the stomach: A review of 67 cases. Cancer. 1990;65(7):1596–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molina Infante J, Beceiro Pedreño I, Ripoll Noiseux C, et al. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to metastatic choriocarcinoma with gastric and colonic involvement. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2004;96(1):77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura A, Ikeda Y, Morishita S, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding arising from metastatic testicular tumor. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(5):650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanthan R, Sharanowski K, Senger JL, et al. Uncommon mucosal metastases to the stomach. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]