Abstract

The association between cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) -1195G>A (rs689466) polymorphism and cancer risk has been extensively explored. However, the results of previous studies remain controversial. To address this gap, we performed an updated meta-analysis of fifty-eight studies involving a total of 50,672 subjects. Searching of PubMed and Embase databases was performed for publications on the association between COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and the risk of cancer. Statistical correlation was identified between COX-2 -1195G>A variants and overall cancer risk in five genetic models. In a sub-group analysis based on cancer type, significant association between COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and increased risk of gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and other cancers was found. In a sub-group analysis by ethnicity, increased cancer risk was observed among Asians instead of Caucasians, Africans and mixed populations. Furthermore, in a sub-group analysis based on cancer system, increased cancer risk was found in digestive system cancer and other system cancer. Non-parametric “trim-and-fill” method was harnessed as a sensitivity analysis method and the results suggested our findings reliable. In summary, the results of our meta-analysis highlight that COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism may be a risk factor for cancer.

Keywords: Cancer, gene polymorphism, cyclooxygenase-2, meta-analysis

Introduction

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that carcinogenesis is a multi-step and multi-factorial process that results from complex interactions of both environmental and genetic factors. The pathogenesis of malignance is very complicated and has not been clarified completely, although recent studies have kept a watchful eye on the role of the chronic infection and immune system [1,2]. Recently, evidence highlights that inflammatory factors of chronic infection may have a hand in the development of multiple cancers by mediating immune suppression, suppressing apoptosis and promoting cell proliferation [3-5]. For this reason, chronic infection is increasing as a hot spot in clinical and experimental cancer research [6,7].

Inflammatory factors of chronic infection have long been considered as a risk candidate for multiple human malignances [8-11]. Of late, Wang reported that the modifiable risk factors elucidate nearly 60% of cancer related deaths in China, with a prominent role of tobacco consumption and chronic infection [12].

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), an inducible enzyme, converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandins which are the effective mediators of inflammation reaction. It is reported that COX-2 is over-expressed in tumor tissue specimens, whereas in normal tissue, its expression is often undetectable [13,14]. Previous clinical and experimental investigation suggested that COX-1/-2 inhibitor attenuates the risk of carcinoma [15].

Of late, the association between COX-2 -1195G>A (rs689466) and cancer risk was extensively explored. Previous studies supported that COX-2 -1195G>A was associated with increased risk of overall cancer, especially in non-nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug users [16-18]. Recently, more investigations were performed to validate this potential correlation. Up to now, fifty-eight studies focus on the association of COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism with malignance, and the results remain conflicting. The aim of our study was to extensively investigate the association between COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and cancer risk by an updated meta-analysis.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

All publications investigating the association between COX-2 -1195G>A and cancer risk were identified by exhausted electronic literature searches of PubMed and Embase databases (published up to July 31, 2014) with search terms of ‘COX2’, ‘COX-2’, ‘Cyclooxygenase-2’, ‘Cyclooxygenase 2’, ‘rs689466’, ‘polymorphism’, ‘mutation’, ‘locus’, ‘SNP’, ‘neoplasm’, ‘carcinoma’, ‘cancer’, ‘tumor’, and ‘malignance’. Additionally, in searching, no language was restricted. The citations in retrieved publications, published reviews, comments and letters were also scanned for relevant publications.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included studies had to meet the following criteria: 1) they should be case-control or cohort study design; 2) they should focus on the association between COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and cancer; 3) they should supply the available frequencies of genotypes or alleles; 4) genotype distributions among controls were consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). The major exclusion criteria were: 1) no usable data reported; 2) overlapping data; 3) only relevant to oncotherapy; not case-control study or cohort study design; 5) comment, review, editorial, meta-analysis or letter.

Data extraction

In a standardized form, three researchers (Y. Wang, H. Jiang and T. Liu) extracted the data independently and the following items were extracted: the first author’s last name, year of publication, cancer type, country, populations, genotype frequencies and sample size (total cases and controls), genotype method. When we meet conflicting evaluations, differences were adjudicated and reached a consensus on all of the items after discussion among all reviewers.

Statistical analysis

Crude odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated to evaluate the strength of association between COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and cancer risk. The pooled ORs were conducted for five genetic models including allele comparing model (A vs. G), dominant model (AA+GA vs. GG), recessive model (AA vs. GA+GG), heterozygote comparison (GA vs. GG) and homozygote comparison (AA vs. GG). P < 0.05 (two tailed) was defined as statistically significant. We also performed stratification analyses by cancer type (any cancer type < 3 individual case-control studies was defined as ‘other cancers’), ethnicity and system. Heterogeneity was calculated by a chi square-based Q statistical and I2 test. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.1 or I2 > 50% and a random effect model (the DerSimonian-Laird method) was used [19], otherwise a fixed-effect model (the Mantel-Haenszel method) was applied [20]. A web-based HWE program (http://ihg.gsf.de/cgi-bin/hw/hwa1.pl) was harnessed to assess the evidence of HWE in controls. The potential publication bias was measured by the Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test. The statistical significance level was set at 0.05. Nonparametric “trim-and-fill” method was used to determine the stability of our results. All the statistical manipulations were performed using STATA (Version 12.0) statistical software (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas).

Results

Studies characteristics

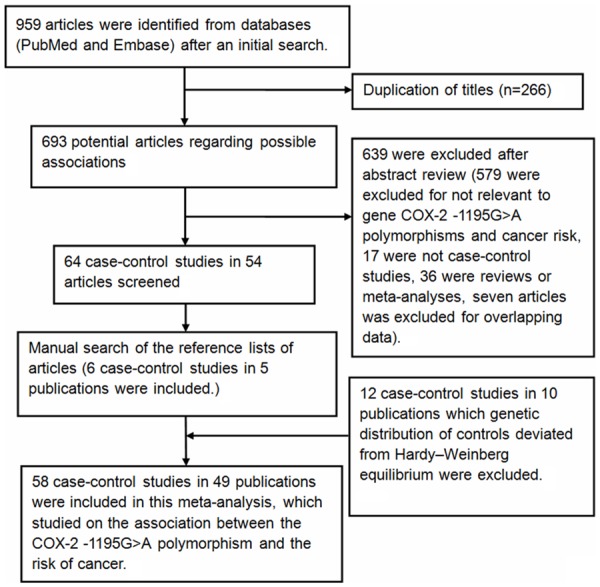

A total of 959 relevant publications were retrieved from electronic literature searches. The detailed selecting process was presented in Figure 1. In some publications, there were more than two independent groups, which were treated separately as individual studies [21-26]. Lastly, fifty-eight studies on the association of COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism with cancer risk were pooled [22,27-57]. Among them, eleven investigated colorectal cancer [21,26,34,55,58-60], eight investigated esophageal cancer [22,43,44,46,61,62], six investigated hepatocellular carcinoma [33,38,42,50,63,64], five investigated prostate cancer [29,36,57,65], four investigated gastric cancer [31,32,52,53], four investigated lymphoma [24,56], four investigated breast cancer [27,51,54,66], three investigated pancreatic cancer [47,48,67], and the others investigated gallbladder cancer [45], bladder cancer [30,37], head and neck cancer [28,68], leukemia [35,39], lung cancer [41,69], skin cancer [70,71] and oral cancer [40,49]. With respect to subjects, twenty-seven were Asians [27-53], twenty-five were Caucasians [21,24,26,57-71], four were mixed populations [22,54-56] and two were Africans [22,57]. Table 1 gives characteristics and Table 2 gives COX-2 -1195G>A genotype and allele frequencies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the study selection procedure in meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies in the meta-analysis

| Study | Publication year | Ethnicity | Country | Cancer type | Sample size (case/control) | Genotype method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moatter et al. | 2014 | Asians | Pakistan | breast cancer | 150/101 | PCR-RFLP |

| Gharib et al. | 2014 | Caucasians | Egypt | hepatocellular carcinoma | 120/130 | PCR-RFLP |

| Niu et al. | 2014 | Asians | China | head and neck cancer | 260/1047 | TaqMan |

| Sugie et al. | 2014 | Asians | Japan | prostate cancer | 134/86 | PCR-RFLP |

| Pereira et al. | 2014 | Caucasians | Portugal | colorectal cancer | 246/480 | MassARRAY iPLEX Gold technology |

| Chang et al. | 2013 | Asians | China | bladder cancer | 375/375 | PCR-RFLP |

| Andersen et al. | 2013 | Caucasians | Denmark | colorectal cancer | 970/1789 | KASP™ genotyping assay |

| Makar et al. | 2013 | Caucasians | USA | colorectal cancer | 1470/1837 | IlluminaTM GoldenGate |

| Makar et al. | 2013 | Caucasians | USA | colorectal cancer | 583/775 | IlluminaTM GoldenGate |

| Makar et al. | 2013 | Caucasians | USA | colorectal cancer | 959/1535 | IlluminaTM GoldenGate |

| Makar et al. | 2013 | Caucasians | USA | colorectal cancer | 505/839 | IlluminaTM GoldenGate |

| Kopp et al. | 2013 | Caucasians | Denmark | prostate cancer | 334/334 | RT-PCR |

| Shin et al. | 2012 | Asians | Korea | gastric cancer | 100/100 | PCR-RFLP |

| Li et al. | 2012 | Asians | China | gastric cancer | 296/319 | PCR-RFLP |

| Chang et al. | 2012 | Asians | China | hepatocellular carcinoma | 298/298 | PCR-RFLP |

| Zhang et al. | 2012 | Asians | China | colorectal cancer | 343/340 | PCR-RFLP |

| Talar-Wojnarowska et al. | 2011 | Caucasians | Poland | pancreatic cancer | 85/116 | PCR-RFLP |

| Bye et al. | 2011 | Africans | South Africa | esophageal cancer | 358/477 | TaqMan |

| Bye et al. | 2011 | mixed | South Africa | esophageal cancer | 201/427 | TaqMan |

| Zheng et al. | 2011 | Asians | China | leukemia | 446/725 | PCR-RFLP |

| Wu et al. | 2011 | Asians | China | prostate cancer | 218/436 | PCR-RFLP |

| Akkiz et al. | 2011 | Caucasians | Turkey | hepatocellular carcinoma | 129/129 | PCR-RFLP |

| Brasky et al. | 2011 | Caucasians | USA | breast cancer | 1077/1910 | RT-PCR |

| Gangwar et al. | 2011 | Asians | India | bladder cancer | 212/250 | PCR-RFLP |

| Fan et al. | 2011 | Asians | China | hepatocellular carcinoma | 780/780 | TaqMan |

| Piranda et al. | 2010 | mixed | Brazil | breast cancer | 318/273 | PCR-RFLP |

| Wang et al. | 2010 | Asians | China | leukemia | 266/266 | PCR-RFLP |

| Mittal et al. | 2010 | Asians | India | oral cancer | 193/137 | PCR-RFLP |

| Liu et al. | 2010 | Asians | China | lung cancer | 358/716 | PCR-RFLP |

| Liu et al. | 2010 | Asians | China | hepatocellular carcinoma | 210/210 | PCR–RFLP |

| Chen et al. | 2009 | Asians | China | esophageal cancer | 188/324 | PCR-RFLP |

| Hoff et al. | 2009 | Caucasians | The Netherlands | colorectal cancer | 326/369 | PCR-RFLP |

| Kristinsson et al. | 2009 | Caucasians | The Netherlands | esophageal cancer | 174/240 | PCR-RFLP |

| Kristinsson et al. | 2009 | Caucasians | The Netherlands | esophageal cancer | 70/240 | PCR-RFLP |

| Hu et al. | 2009 | Asians | China | esophageal cancer | 180/194 | PCR-RFLP |

| Srivastava et al. | 2009 | Asians | India | gallbladder cancer | 167/184 | PCR-RFLP |

| Thompson et al. | 2009 | mixed | USA | colorectal cancer | 422/481 | Taqman |

| Upadhyay et al. | 2009 | Asians | India | esophageal cancer | 174/216 | PCR-RFLP |

| Zhao et al. | 2009 | Asians | China | pancreatic cancer | 393/786 | PCR-RFLP |

| Peters et al. | 2009 | Caucasians | The Netherlands | head and neck cancer | 431/438 | PCR-RFLP |

| Chang et al. | 2009 | mixed | USA | lymphoma | 473/373 | TaqMan |

| Xu et al. | 2008 | Asians | China | pancreatic cancer | 283/566 | PCR-RFLP |

| Chiang et al. | 2008 | Asians | China | oral cancer | 377/442 | PCR-RFLP |

| Vogel et al. | 2008 | Caucasians | Denmark | lung cancer | 403/744 | TaqMan |

| Hoeft et al. | 2008 | Caucasians | Germany | lymphoma | 554/710 | TaqMan |

| Hoeft et al. | 2008 | Caucasians | Germany | lymphoma | 35/710 | TaqMan |

| Hoeft et al. | 2008 | Caucasians | Germany | lymphoma | 116/710 | TaqMan |

| Xu et al. | 2008 | Asians | China | hepatocellular carcinoma | 270/540 | PCR-RFLP |

| Cheng et al. | 2007 | Africans | USA | prostate cancer | 89/506 | Taqman |

| Cheng et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | USA | prostate cancer | 417/506 | Taqman |

| Moons et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | The Netherlands | esophageal cancer | 140/240 | PCR-RFLP |

| Lira et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | Italy | skin cancer | 107/133 | PCR-RFLP |

| Gao et al. | 2007 | Asians | China | breast cancer | 615/643 | PCR-RFLP |

| Vogel et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | Denmark | skin cancer | 322/322 | Taqman |

| Jiang et al. | 2007 | Asians | China | gastric cancer | 254/304 | PCR-RFLP |

| Siezen et al. | 2006 | Caucasians | Netherlands | colorectal cancer | 204/399 | PCR-RFLP |

| Siezen et al. | 2006 | Caucasians | Netherlands | colorectal cancer | 304/373 | PCR-RFLP |

| Liu et al. | 2006 | Asians | China | gastric cancer | 248/1523 | DHPLC |

PCR-RFLP: polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism; DHPLC: denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography analysis.

Table 2.

COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism genotype distribution and allele frequency

| Study | Publication year | Case | Control | Case | Control | HWE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| GG | GA | AA | GG | GA | AA | A | G | A | G | |||

| Moatter et al. | 2014 | 4 | 19 | 112 | 3 | 21 | 77 | 243 | 27 | 175 | 27 | 0.304270 |

| Gharib et al. | 2014 | 17 | 60 | 43 | 31 | 66 | 33 | 146 | 94 | 132 | 128 | 0.858603 |

| Niu et al. | 2014 | 61 | 126 | 72 | 222 | 542 | 271 | 270 | 248 | 1084 | 986 | 0.109869 |

| Sugie et al. | 2014 | 21 | 61 | 52 | 20 | 47 | 19 | 165 | 103 | 85 | 87 | 0.387570 |

| Pereira et al. | 2014 | 15 | 85 | 143 | 16 | 133 | 323 | 371 | 115 | 779 | 165 | 0.614121 |

| Chang et al. | 2013 | 89 | 181 | 105 | 97 | 171 | 107 | 391 | 359 | 385 | 365 | 0.090733 |

| Andersen et al. | 2013 | 47 | 313 | 587 | 61 | 560 | 1126 | 1487 | 407 | 2812 | 682 | 0.397081 |

| Makar et al. | 2013 | 57 | 455 | 910 | 67 | 509 | 1198 | 2275 | 569 | 2905 | 643 | 0.162224 |

| Makar et al. | 2013 | 20 | 185 | 376 | 29 | 237 | 509 | 937 | 225 | 1255 | 295 | 0.828845 |

| Makar et al. | 2013 | 33 | 287 | 619 | 63 | 496 | 958 | 1525 | 353 | 2412 | 622 | 0.904941 |

| Makar et al. | 2013 | 21 | 138 | 338 | 20 | 249 | 558 | 814 | 180 | 1365 | 289 | 0.205656 |

| Kopp et al. | 2013 | 13 | 111 | 210 | 12 | 112 | 210 | 531 | 137 | 532 | 136 | 0.533685 |

| Shin et al. | 2012 | 14 | 54 | 32 | 22 | 41 | 37 | 118 | 82 | 115 | 85 | 0.107125 |

| Li et al. | 2012 | 53 | 145 | 98 | 80 | 166 | 73 | 341 | 251 | 312 | 326 | 0.461235 |

| Chang et al. | 2012 | 70 | 144 | 84 | 74 | 145 | 81 | 312 | 284 | 307 | 293 | 0.569879 |

| Zhang et al. | 2012 | 50 | 216 | 77 | 94 | 184 | 62 | 370 | 316 | 308 | 372 | 0.089719 |

| Talar-Wojnarowska et al. | 2011 | 13 | 26 | 46 | 44 | 48 | 24 | 118 | 52 | 96 | 136 | 0.113223 |

| Bye et al. | 2011 | 0 | 44 | 301 | 1 | 47 | 417 | 646 | 44 | 881 | 49 | 0.786975 |

| Bye et al. | 2011 | 0 | 40 | 154 | 9 | 112 | 298 | 348 | 40 | 708 | 130 | 0.686305 |

| Zheng et al. | 2011 | 100 | 222 | 124 | 176 | 365 | 184 | 470 | 422 | 733 | 717 | 0.850095 |

| Wu et al. | 2011 | 57 | 100 | 61 | 104 | 210 | 122 | 222 | 214 | 454 | 418 | 0.464218 |

| Akkiz et al. | 2011 | 2 | 36 | 91 | 2 | 32 | 95 | 218 | 40 | 222 | 36 | 0.707524 |

| Brasky et al. | 2011 | 34 | 271 | 660 | 54 | 471 | 1199 | 1591 | 339 | 2869 | 579 | 0.353199 |

| Gangwar et al. | 2011 | 162 | 48 | 2 | 182 | 64 | 4 | 52 | 372 | 72 | 428 | 0.543520 |

| Fan et al. | 2011 | 204 | 390 | 186 | 205 | 381 | 194 | 762 | 798 | 769 | 791 | 0.522773 |

| Piranda et al. | 2010 | 3 | 62 | 224 | 3 | 51 | 190 | 510 | 68 | 431 | 57 | 0.838274 |

| Wang et al. | 2010 | 63 | 128 | 75 | 65 | 127 | 74 | 278 | 254 | 275 | 257 | 0.472808 |

| Mittal et al. | 2010 | 3 | 57 | 133 | 5 | 32 | 100 | 323 | 63 | 232 | 42 | 0.241040 |

| Liu et al. | 2010 | 84 | 172 | 102 | 178 | 345 | 193 | 376 | 340 | 731 | 701 | 0.336883 |

| Liu et al. | 2010 | 31 | 110 | 69 | 52 | 108 | 50 | 248 | 172 | 208 | 212 | 0.677855 |

| Chen et al. | 2009 | 42 | 88 | 58 | 57 | 165 | 102 | 204 | 172 | 369 | 279 | 0.487719 |

| Hoff et al. | 2009 | 12 | 101 | 213 | 13 | 124 | 232 | 527 | 125 | 588 | 150 | 0.470706 |

| Kristinsson et al. | 2009 | 15 | 59 | 100 | 6 | 80 | 154 | 259 | 89 | 388 | 92 | 0.240585 |

| Kristinsson et al. | 2009 | 5 | 26 | 39 | 6 | 80 | 154 | 104 | 36 | 388 | 92 | 0.240585 |

| Hu et al. | 2009 | 39 | 80 | 61 | 50 | 103 | 41 | 202 | 158 | 185 | 203 | 0.371617 |

| Srivastava et al. | 2009 | 104 | 52 | 11 | 142 | 37 | 5 | 74 | 260 | 47 | 321 | 0.185970 |

| Thompson et al. | 2009 | 9 | 138 | 275 | 15 | 168 | 297 | 688 | 156 | 762 | 198 | 0.130845 |

| Upadhyay et al. | 2009 | 126 | 46 | 2 | 168 | 45 | 3 | 50 | 298 | 51 | 381 | 0.994569 |

| Zhao et al. | 2009 | 85 | 194 | 114 | 212 | 401 | 173 | 422 | 364 | 747 | 825 | 0.521326 |

| Peters et al. | 2009 | 22 | 134 | 275 | 15 | 163 | 260 | 684 | 178 | 683 | 193 | 0.081594 |

| Chang et al. | 2009 | 19 | 124 | 314 | 13 | 99 | 249 | 752 | 162 | 597 | 125 | 0.422989 |

| Xu et al. | 2008 | 58 | 143 | 82 | 154 | 284 | 128 | 307 | 259 | 540 | 592 | 0.892966 |

| Chiang et al. | 2008 | 80 | 187 | 101 | 114 | 235 | 93 | 389 | 347 | 421 | 463 | 0.166848 |

| Vogel et al. | 2008 | 17 | 124 | 262 | 24 | 253 | 467 | 648 | 158 | 1187 | 301 | 0.143186 |

| Hoeft et al. | 2008 | 14 | 147 | 361 | 19 | 197 | 447 | 869 | 175 | 1091 | 235 | 0.627123 |

| Hoeft et al. | 2008 | 1 | 13 | 19 | 19 | 197 | 447 | 51 | 15 | 1091 | 235 | 0.627123 |

| Hoeft et al. | 2008 | 1 | 33 | 76 | 19 | 197 | 447 | 185 | 35 | 1091 | 235 | 0.627123 |

| Xu et al. | 2008 | 52 | 125 | 93 | 119 | 287 | 134 | 311 | 229 | 555 | 525 | 0.138287 |

| Cheng et al. | 2007 | 2 | 20 | 67 | 0 | 12 | 77 | 154 | 24 | 166 | 12 | 0.495255 |

| Cheng et al. | 2007 | 13 | 134 | 270 | 15 | 122 | 280 | 674 | 160 | 682 | 152 | 0.705855 |

| Moons et al. | 2007 | 3 | 54 | 83 | 10 | 76 | 154 | 220 | 60 | 384 | 96 | 0.871799 |

| Lira et al. | 2007 | 3 | 25 | 76 | 2 | 33 | 96 | 177 | 31 | 225 | 37 | 0.658979 |

| Gao et al. | 2007 | 121 | 305 | 175 | 150 | 327 | 166 | 655 | 547 | 659 | 627 | 0.652871 |

| Vogel et al. | 2007 | 10 | 95 | 199 | 15 | 121 | 179 | 493 | 115 | 479 | 151 | 0.338448 |

| Jiang et al. | 2007 | 48 | 132 | 74 | 62 | 163 | 79 | 280 | 228 | 321 | 287 | 0.186688 |

| Siezen et al. | 2006 | 10 | 59 | 127 | 20 | 128 | 243 | 313 | 79 | 614 | 168 | 0.557997 |

| Siezen et al. | 2006 | 19 | 132 | 283 | 41 | 226 | 422 | 698 | 170 | 1070 | 308 | 0.148689 |

| Liu et al. | 2006 | 44 | 116 | 88 | 377 | 771 | 375 | 292 | 204 | 1521 | 1525 | 0.626310 |

HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Meta-analysis results

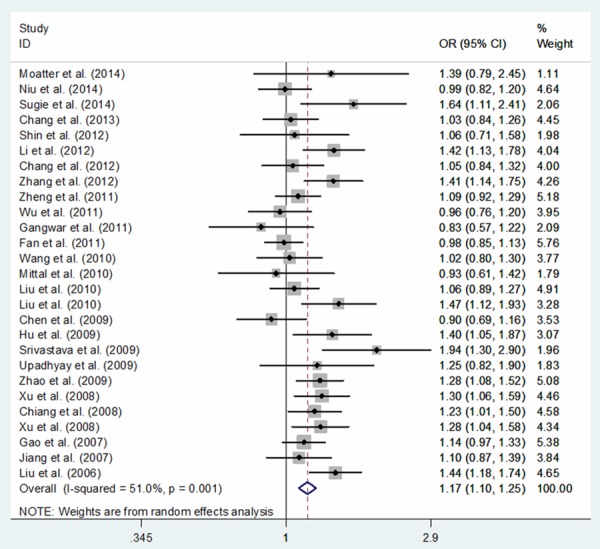

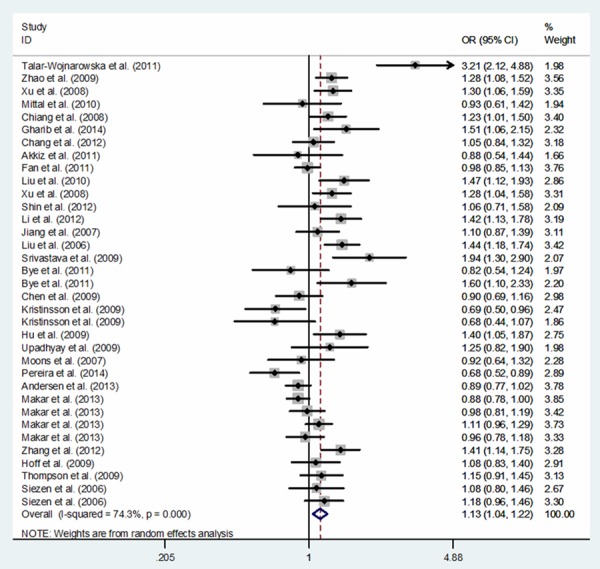

In total, 50,672 subjects (19,947 cases and 30,725 controls) were relevant to the association between COX-2 -1195G>A and cancer risk. Overall, significantly increased cancer risk was associated with the COX-2 -1195A allele: dominant model comparison AA+GA vs. GG (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.04-1.25; P = 0.007), recessive model comparison AA vs. GA+GG (OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.04-1.18; P = 0.003), homozygote comparison AA vs. GG (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.07-1.36; P = 0.002), heterozygote comparison GA vs. GG (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.00-1.18; P = 0.045) and allele comparison A vs. G (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.03-1.15; P = 0.002) (Table 3). In a sub-group analysis based on cancer type, the association between COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and an increased risk of gastric cancer was identified in five genetic models: AA+GA vs. GG (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.15-1.76; P = 0.001), AA vs. GA+GG (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81; P = 0.036), AA vs. GG (OR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.35-2.20; P < 0.001), GA vs. GG (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.02-1.60; P = 0.031) and A vs. G (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.16-1.47; P < 0.001), of pancreatic cancer in five genetic models: AA+GA vs. GG (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.12-2.48; P = 0.012), AA vs. GA+GG (OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.14-3.30; P = 0.015), AA vs. GG (OR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.27-4.40; P = 0.007), GA vs. GG (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.04-1.62; P = 0.022) and A vs. G (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.11-2.47; P = 0.013), of hepatocellular carcinoma in one genetic model: AA vs. GG (OR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.02-2.00; P = 0.039) and of other cancers in two genetic models: AA vs. GA+GG (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.03-1.25; P = 0.009) and A vs. G (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.02-1.16; P = 0.011) (Table 4). In a sub-group analysis by ethnicity, our results confirmed that COX-2 -1195A allele was associated with an increased cancer risk in Asians: AA+GA vs. GG (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.10-1.34; P < 0.001), AA vs. GA+GG (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.12-1.35; P < 0.001), AA vs. GG (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.20-1.55; P < 0.001), GA vs. GG (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.05-1.26; P = 0.003) and A vs. G (OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.10-1.25; P < 0.001), a borderline decreased cancer risk was identified in two genetic models: AA vs. GA+GG (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.48-1.01; P = 0.058) and A vs. G (OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.49-1.01; P = 0.056) in Africans, but not in Caucasians or mixed populations (Table 3; Figure 2). Additionally, in a sub-group analysis based on cancer system, a significant increased risk of digestive system cancer was confirmed in five genetic models: AA+GA vs. GG (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.06-1.39; P = 0.004), AA vs. GA+GG (OR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.04-1.26; P = 0.008), AA vs. GG (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.10-1.57; P = 0.003), GA vs. GG (OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.30; P = 0.018) and A vs. G (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.04-1.22; P = 0.003) and of other system cancer in one genetic model: AA vs. GA+GG (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.02-1.42; P = 0.026) (Table 5; Figure 3).

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphisms and cancer risk in a sub-group analysis by race

| Genetic comparison | Population | OR (95% CI); P | Test of heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| (p-Value, I2) | Model | |||

| AA+GA vs. GG | All | 1.14 (1.04-1.25); 0.007 | < 0.001, 43.4% | R |

| Asians | 1.22 (1.10-1.34); < 0.001 | 0.014, 41.4% | R | |

| Caucasians | 0.97 (0.80-1.17); 0.716 | 0.009, 44.6% | R | |

| Africans | 0.58 (0.09-3.61);0.556 | 0.280, 14.4% | F | |

| Mixed | 1.28 (0.79-2.08); 0.321 | 0.378, 2.9% | F | |

| AA vs. GA+GG | All | 1.11 (1.04-1.18); 0.003 | < 0.001, 56.5% | R |

| Asians | 1.23 (1.12-1.35); < 0.001 | 0.024, 38.3% | R | |

| Caucasians | 1.02 (0.93-1.12); 0.660 | < 0.001, 58.6% | R | |

| Africans | 0.69 (0.48-1.01); 0.058 | 0.265, 19.7% | F | |

| Mixed | 1.13 (0.96-1.33); 0.148 | 0.294, 19.2% | F | |

| AA vs. GG | All | 1.21 (1.07-1.36); 0.002 | < 0.001, 54.4% | R |

| Asians | 1.36 (1.20-1.55); < 0.001 | 0.006, 45.6% | R | |

| Caucasians | 0.99 (0.79-1.24); 0.940 | < 0.001, 57.9% | R | |

| Africans | 0.54 (0.09-3.31); 0.501 | 0.263, 20.0% | F | |

| Mixed | 1.31 (0.81-2.14); 0.273 | 0.338, 10.9% | F | |

| GA vs. GG | All | 1.09 (1.00-1.18); 0.045 | 0.073, 22.2% | R |

| Asians | 1.15 (1.05-1.26); 0.003 | 0.085, 28.5% | R | |

| Caucasians | 0.94 (0.82-1.08); 0.375 | 0.281, 12.8% | F | |

| Africans | 0.89 (0.13-6.02); 0.903 | 0.348, 0.0% | F | |

| Mixed | 1.22 (0.73-2.02); 0.451 | 0.513, 0.0% | F | |

| A vs. G | All | 1.09 (1.03-1.15); 0.002 | < 0.001, 63.9% | R |

| Asians | 1.17 (1.10-1.25); < 0.001 | 0.001, 51.0% | R | |

| Caucasians | 1.02 (0.93-1.11); 0.720 | < 0.001, 66.1% | R | |

| Africans | 0.70 (0.49-1.01); 0.056 | 0.186, 42.7% | F | |

| Mixed | 1.12 (0.97-1.30); 0.115 | 0.170, 40.3% | F | |

F indicates fixed model; R indicates random model.

Table 4.

Meta-analysis of COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphisms and cancer risk in a sub-group analysis by cancer type

| Genetic comparison | Cancer type | OR (95% CI); P | Test of heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| (p-Value, I2) | Model | |||

| AA+GA vs. GG | All | 1.14 (1.04-1.25); 0.007 | < 0.001, 43.4% | R |

| Breast cancer | 1.11 (0.88-1.39); 0.374 | 0.700, 0.0% | F | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1.16 (0.99-1.36); 0.060 | 0.169, 35.7% | F | |

| Prostate cancer | 1.00 (0.76-1.33); 0.984 | 0.453, 0.0% | F | |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.03 (0.78-1.36); 0.848 | 0.001, 65.6% | R | |

| Gastric cancer | 1.43 (1.15-1.76); 0.001 | 0.568, 0.0% | F | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.66 (1.12-2.48); 0.012 | 0.054, 65.8% | R | |

| Esophageal cancer | 0.91 (0.56-1.47); 0.697 | 0.013, 60.5% | R | |

| Lymphoma | 1.07 (0.67-1.70); 0.776 | 0.682, 0.0% | F | |

| Other cancers | 1.08 (0.96-1.21); 0.179 | 0.158, 28.5% | F | |

| AA vs. GA+GG | All | 1.11 (1.04-1.18); 0.003 | < 0.001, 56.5% | R |

| Breast cancer | 1.03 (0.90-1.17); 0.665 | 0.316, 15.1% | F | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1.22 (0.96-1.54); 0.100 | 0.040, 57.1% | R | |

| Prostate cancer | 1.01 (0.74-1.36); 0.962 | 0.031, 62.3% | R | |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.00 (0.91-1.11); 0.926 | 0.030, 49.9% | R | |

| Gastric cancer | 1.36 (1.02-1.81); 0.036 | 0.076, 56.3% | R | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.93 (1.14-3.30); 0.015 | 0.002, 83.3% | R | |

| Esophageal cancer | 1.00 (0.76-1.31); 0.989 | 0.013, 60.8% | R | |

| Lymphoma | 1.02 (0.86-1.21); 0.795 | 0.608, 0.0% | F | |

| Other cancers | 1.14 (1.03-1.25); 0.009 | 0.601, 0.0% | F | |

| AA vs. GG | All | 1.21 (1.07-1.36);0.002 | < 0.001, 54.4% | R |

| Breast cancer | 1.14 (0.88-1.47); 0.316 | 0.551, 0.0% | F | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1.43 (1.02-2.00); 0.039 | 0.032, 59.2% | R | |

| Prostate cancer | 1.08 (0.79-1.48); 0.619 | 0.156, 39.9% | F | |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.02 (0.78-1.35); 0.880 | 0.003, 62.7% | R | |

| Gastric cancer | 1.72 (1.35-2.20); < 0.001 | 0.336, 11.3% | F | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 2.36 (1.27-4.40); 0.007 | 0.006, 80.4% | R | |

| Esophageal cancer | 0.90 (0.46-1.77); 0.770 | 0.005, 65.1% | R | |

| Lymphoma | 1.07 (0.67-1.71); 0.761 | 0.668, 0.0% | F | |

| Other cancers | 1.13 (0.98-1.30); 0.090 | 0.427, 1.9% | F | |

| GA vs. GG | All | 1.09 (1.00-1.18); 0.045 | 0.073, 22.2% | R |

| Breast cancer | 1.07 (0.85-1.36); 0.556 | 0.784, 0.0% | F | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1.11 (0.94-1.31); 0.201 | 0.450, 0.0% | F | |

| Prostate cancer | 0.97 (0.72-1.30); 0.837 | 0.799, 0.0% | F | |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.03 (0.80-1.34); 0.798 | 0.009, 57.3% | R | |

| Gastric cancer | 1.28 (1.02-1.60); 0.031 | 0.518, 0.0% | F | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.30 (1.04-1.62); 0.022 | 0.608, 0.0% | F | |

| Esophageal cancer | 0.90 (0.58-1.42); 0.661 | 0.040, 52.4% | R | |

| Lymphoma | 1.06 (0.66-1.71); 0.812 | 0.692, 0.0% | F | |

| Other cancers | 1.04 (0.92-1.17); 0.531 | 0.193, 24.8% | F | |

| A vs. G | All | 1.09 (1.03-1.15); 0.002 | < 0.001, 63.9% | R |

| Breast cancer | 1.04 (0.94-1.15); 0.458 | 0.274, 22.9% | F | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1.17 (0.99-1.38); 0.057 | 0.026, 60.7% | R | |

| Prostate cancer | 1.00 (0.79-1.26); 0.976 | 0.027, 63.5% | R | |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.02 (0.92-1.13); 0.737 | 0.001, 67.9% | R | |

| Gastric cancer | 1.30 (1.16-1.47); < 0.001 | 0.209, 33.9% | F | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.66 (1.11-2.47); 0.013 | < 0.001, 88.1% | R | |

| Esophageal cancer | 0.99 (0.80-1.23); 0.936 | 0.003, 67.9% | R | |

| Lymphoma | 1.02 (0.88-1.19); 0.752 | 0.608, 0.0% | F | |

| Other cancers | 1.09 (1.02-1.16); 0.011 | 0.170, 27.2% | F | |

F indicates fixed model; R indicates random model.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and cancer risk in Asians: allele comparing model.

Table 5.

Meta-analysis of COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphisms and cancer risk in a sub-group analysis by cancer system

| Genetic comparison | Cancer system | OR (95% CI); P | Test of heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| (p-Value, I2) | Model | |||

| AA+GA vs. GG | All | 1.14 (1.04-1.25); 0.007 | < 0.001, 43.4% | R |

| Reproductive and breast cancer | 1.11 (0.88-1.39); 0.374 | 0.700, 0.0% | F | |

| Digestive system cancer | 1.22 (1.06-1.39); 0.004 | < 0.001, 57.8% | R | |

| Urogenital cancer | 1.00 (0.83-1.21); 0.999 | 0.555, 0.0% | F | |

| hematological malignancy | 1.08 (0.88-1.33); 0.445 | 0.903, 0.0% | F | |

| Respiratory system cancer | 1.01 (0.77-1.33); 0.919 | 0.320, 0.0% | F | |

| Other system cancer | 0.88 (0.67-1.16); 0.364 | 0.466, 0.0% | F | |

| AA vs. GA+GG | All | 1.11 (1.04-1.18); 0.003 | < 0.001, 56.5% | R |

| Reproductive and breast cancer | 1.03 (0.90-1.17); 0.665 | 0.316, 15.1% | F | |

| Digestive system cancer | 1.14 (1.04-1.26); 0.008 | < 0.001, 68.6% | R | |

| Urogenital cancer | 0.99 (0.79-1.24); 0.923 | 0.090, 45.3% | R | |

| hematological malignancy | 1.05 (0.92-1.20); 0.487 | 0.811, 0.0% | F | |

| Respiratory system cancer | 1.09 (0.90-1.32); 0.359 | 0.915, 0.0% | F | |

| Other system cancer | 1.21 (1.02-1.42); 0.026 | 0.563, 0.0% | F | |

| AA vs. GG | All | 1.21 (1.07-1.36); 0.002 | < 0.001, 54.4% | R |

| Reproductive and breast cancer | 1.14 (0.88-1.47); 0.316 | 0.551, 0.0% | F | |

| Digestive system cancer | 1.31 (1.10-1.57); 0.003 | < 0.001, 67.0% | R | |

| Urogenital cancer | 1.06 (0.83-1.35); 0.624 | 0.302, 16.8% | F | |

| hematological malignancy | 1.12 (0.89-1.42); 0.343 | 0.870, 0.0% | F | |

| Respiratory system cancer | 1.03 (0.76-1.41); 0.832 | 0.353, 0.0% | F | |

| Other system cancer | 0.97 (0.71-1.31); 0.821 | 0.420, 0.0% | F | |

| GA vs. GG | All | 1.09 (1.00-1.18); 0.045 | 0.073, 22.2% | R |

| Reproductive and breast cancer | 1.07 (0.85-1.36); 0.556 | 0.784, 0.0% | F | |

| Digestive system cancer | 1.15 (1.02-1.30); 0.018 | 0.008, 40.4% | R | |

| Urogenital cancer | 0.99 (0.81-1.22); 0.951 | 0.819, 0.0% | F | |

| hematological malignancy | 1.06 (0.85-1.32); 0.597 | 0.917, 0.0% | F | |

| Respiratory system cancer | 0.98 (0.73-1.30); 0.876 | 0.256, 22.5% | F | |

| Other system cancer | 0.81 (0.61-1.07); 0.143 | 0.543, 0.0% | F | |

| A vs. G | All | 1.09 (1.03-1.15); 0.002 | < 0.001, 63.9% | R |

| Reproductive and breast cancer | 1.04 (0.94-1.15); 0.458 | 0.274, 22.9% | F | |

| Digestive system cancer | 1.13 (1.04-1.22); 0.003 | < 0.001, 74.3% | R | |

| Urogenital cancer | 0.99 (0.84-1.16); 0.871 | 0.063, 49.8% | R | |

| hematological malignancy | 1.05 (0.95-1.16); 0.370 | 0.822, 0.0% | F | |

| Respiratory system cancer | 1.05 (0.92-1.21); 0.471 | 0.891, 0.0% | F | |

| Other system cancer | 1.08 (0.96-1.23); 0.206 | 0.302, 17.7% | F | |

F indicates fixed model; R indicates random model.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and cancer risk in digestive cancer system: allele comparing model.

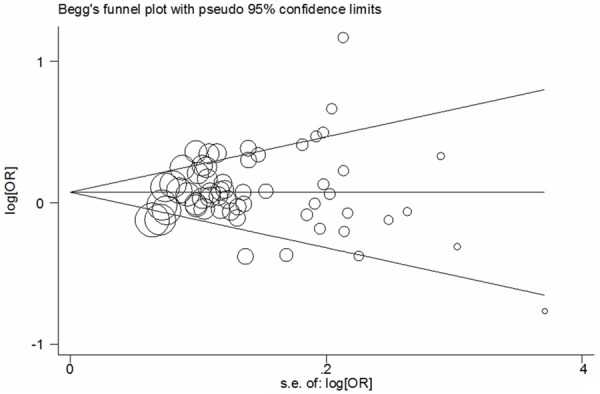

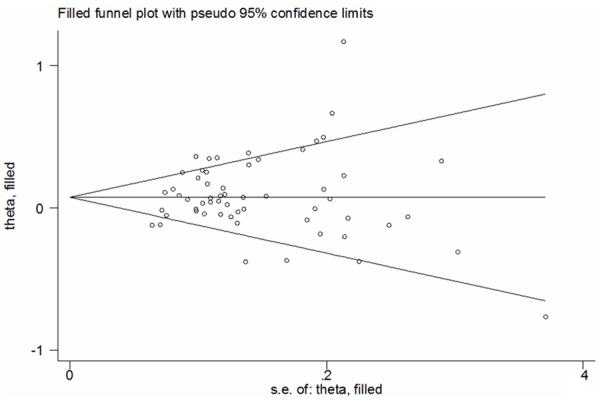

Publication bias

Results of Funnel plots and the Egger’s test indicated that there was no publication bias in this meta-analysis (A vs. G: Begg’s test P = 0.872, Egger’s test P = 0.372; AA vs. GG: Begg’s test P = 0.862, Egger’s test P = 0.981; GA vs. GG: Begg’s test P = 0.872, Egger’s test P = 0.908; AA+GA vs. GG: Begg’s test P = 0.995, Egger’s test P = 0.875; AA vs. GA+GG: Begg’s test P = 0.717, Egger’s test P = 0.088; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Begg’s funnel plot analysis for publication bias in overall cancer: allele comparing model.

Sensitivity analyses

Nonparametric “trim-and-fill” method was performed to determine the reliability of our results. The adjusted ORs and CIs were not qualitatively altered, which demonstrated COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism might be a risk factor for overall cancer risk (A vs. G: adjusted pooled OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.03-1.15, P = 0.002; AA vs. GG: adjusted pooled OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.07-1.36, P = 0.002; AA+GA vs. GG: adjusted pooled OR = 1.14, 95% CI: 1.04-1.25, P = 0.007; AA vs. GA+GG: adjusted pooled OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.02-1.18, P = 0.014; GA vs. GG: adjusted pooled OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.00-1.18, P = 0.045; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Filled funnel plot of meta-analysis in overall cancer: allele comparing model.

Heterogeneity

Significant heterogeneity was obvious in each model among the recruited studies. Sub-group analyses were conducted to explore the source of heterogeneity. The results supported that publications conducted in Asians, Caucasians, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, esophageal cancer and digestive system cancer might contribute to the major origin of heterogeneity.

Discussion

In the current meta-analysis, the results indicated that the COX-2 -1195G>A variants increased cancer risk, especially for gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and other cancers, such effect was still found in subgroup of digestive system cancer, other system cancer and Asians. Further investigations of the functional interpretation are warranted to comprehend the mechanisms for our results.

The COX-2 gene is located on chromosome 1q25.2-3 and is composed of ten exons that encode different functional domains. In 5’ region, there are several response elements, such as activation protein-2, nuclear factor kB, transforming growth factor, stimulatory protein-1 and cyclic adenosine monophosphate binding sites [72]. Mutation in these regulatory elements might alter gene transcription. As an example, a locus in one of the COX-2 promoter regions might change binding capacity for certain nuclear proteins, which suggested to be associated with the level of COX-2 expression [72]. A previous report showed that COX-2 -1195G>A variant modified the transcription of the COX-2 promoter, leading to several fold greater expression of COX-2 [73]. Combined with our results, these findings demonstrated that the -1195G>A mutation in COX-2 increased the risk of cancer, perhaps by modifying binding capacity for certain nuclear proteins and promoting the expression of COX-2 gene.

Since cancer types might affect the findings of meta-analysis, subgroup analysis was carried out. The results highlighted that COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism was associated with the risk of gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and other cancers, but not of esophageal cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer or lymphoma, which was consistent with previous meta-analysis [74-76]. However, these results should be explained with very caution. In some subgroups, only three or four studies were recruited for analysis, which might have insufficient power to obtain a reliable result. Therefore, these correlations need to be further confirmed or refuted in larger size, well-designed studies. Because race could also affect the findings, we conducted subgroup analysis. Our results demonstrated the COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism was associated with an increased cancer risk in Asians but not in Caucasians or mixed populations. While in Africans subgroup, a borderline evidence of association between the COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and cancer risk was identified. Considering only two moderate sample size studies were included and the findings might be due to fluke. Further studies should be performed to confirm the possible effects of COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism. In the current meta-analysis, the correlations observed in different system were analyzed as well. The results suggested that COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism was associated with the risk of digestive system cancer, which was consistent with previous study [16].

Compared with the previous meta-analyses, some advantages of current study should be adequately addressed. First of all, it updated all eligible data for COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and the risk of cancer. Then, our results corroborated COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism effected on pancreatic cancer for the first time. Finally, the methodological issues in pooled analysis (e.g., publication bias, sensitivity and heterogeneity), were all well explored. Although the primary results were stable and suggestive, there were some limitations of this analysis, which should be considered when interpreting the results. First of all, in some subgroup, only two or three eligible case-control studies were recruited; therefore, in these subgroups, the results might be a fluke. For example, in Africans, a borderline evidence of association between the COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and cancer risk was identified. In our study, however, only two studies were included, which might have limited the power to get an accurate result. Second, the eligible studies included only published studies, which might lead to bias, although the statistical data did not show it. Thirdly, large inter-study heterogeneity was observed in overall and some subgroups, which meant explanation of our results, should be very cautious. This could be due to other diversities between investigations, such as gender, age, specified type of cancer, ethnicity variations, smoking, drinking, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, different lifestyle factors, other environmental risk factors, selection criteria of subjects, and socio-economic factors as well. For lack of access to original data from the reviewed publications, these factors were not considered. Finally, the data of GWAS were not available; the power of the results might be limited.

In conclusion, the investigation of the relationship between COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphisms and cancer risk is very popular but controversial at present. Our results support that COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of cancer, especially, in gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, digestive system cancer and Asians subgroups. In the future, more large-scale and well-designed epidemiological studies are warranted to validate or refute these findings.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Jiangsu Province Natural Science Foundation (BK2010333, BK2011481).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Deans C, Rose-Zerilli M, Wigmore S, Ross J, Howell M, Jackson A, Grimble R, Fearon K. Host cytokine genotype is related to adverse prognosis and systemic inflammation in gastro-oesophageal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:329–339. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siemes C, Visser LE, Coebergh JW, Splinter TA, Witteman JC, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Pols HA, Stricker BH. C-reactive protein levels, variation in the C-reactive protein gene, and cancer risk: the Rotterdam Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:5216–5222. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gobel C, Breitenbuecher F, Kalkavan H, Hahnel PS, Kasper S, Hoffarth S, Merches K, Schild H, Lang KS, Schuler M. Functional expression cloning identifies COX-2 as a suppressor of antigen-specific cancer immunity. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1568. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tu B, Ma TT, Peng XQ, Wang Q, Yang H, Huang XL. Targeting of COX-2 expression by recombinant adenovirus shRNA attenuates the malignant biological behavior of breast cancer cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:8829–8836. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.20.8829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W, Bergh A, Damber JE. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression correlates with local chronic inflammation and tumor neovascularization in human prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3250–3256. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim PS, Ahmed R. Features of responding T cells in cancer and chronic infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han-You X. Chronic infection and other risk factors of cancer in China and other countries. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:267. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koyi H, Branden E, Gnarpe J, Gnarpe H, Steen B. An association between chronic infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae and lung cancer. A prospective 2-year study. APMIS. 2001;109:572–580. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2001.d01-177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohshima H, Bartsch H. Chronic infections and inflammatory processes as cancer risk factors: possible role of nitric oxide in carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1994;305:253–264. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(94)90245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Speiser DE, Utzschneider DT, Oberle SG, Munz C, Romero P, Zehn D. T cell differentiation in chronic infection and cancer: functional adaptation or exhaustion? Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:768–774. doi: 10.1038/nri3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ringelhan M, Heikenwalder M, Protzer U. Direct effects of hepatitis B virus-encoded proteins and chronic infection in liver cancer development. Dig Dis. 2013;31:138–151. doi: 10.1159/000347209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang JB, Jiang Y, Liang H, Li P, Xiao HJ, Ji J, Xiang W, Shi JF, Fan YG, Li L, Wang D, Deng SS, Chen WQ, Wei WQ, Qiao YL, Boffetta P. Attributable causes of cancer in China. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2983–2989. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakhle YS. COX-2 and cancer: a new approach to an old problem. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:1137–1150. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao Y, Prescott SM. Many actions of cyclooxygenase-2 in cellular dynamics and in cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:279–286. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruud J, Nilsson A, Engstrom Ruud L, Wang W, Nilsberth C, Iresjo BM, Lundholm K, Engblom D, Blomqvist A. Cancer-induced anorexia in tumor-bearing mice is dependent on cyclooxygenase-1. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;29:124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong J, Dai J, Zhang M, Hu Z, Shen H. Potentially functional COX-2 -1195G>A polymorphism increases the risk of digestive system cancers: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1042–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang Z, Nie ZL, Pan Y, Zhang L, Gao L, Zhang Q, Qu L, He B, Song G, Zhang Y, Shukui W. The Cox-2 -1195G>A polymorphism and cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 25 case-control studies. Mutagenesis. 2011;26:729–734. doi: 10.1093/mutage/ger040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagao M, Sato Y, Yamauchi A. A meta-analysis of PTGS1 and PTGS2 polymorphisms and NSAID intake on the risk of developing cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hua Z, Li D, Xiang G, Xu F, Jie G, Fu Z, Jie Z, Da P, Li D. PD-1 polymorphisms are associated with sporadic breast cancer in Chinese Han population of Northeast China. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayram S, Akkiz H, Ulger Y, Bekar A, Akgollu E, Yildirim S. Lack of an association of programmed cell death-1 PD1.3 polymorphism with risk of hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility in Turkish population: a case-control study. Gene. 2012;511:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.09.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makar KW, Poole EM, Resler AJ, Seufert B, Curtin K, Kleinstein SE, Duggan D, Kulmacz RJ, Hsu L, Whitton J, Carlson CS, Rimorin CF, Caan BJ, Baron JA, Potter JD, Slattery ML, Ulrich CM. COX-1 (PTGS1) and COX-2 (PTGS2) polymorphisms, NSAID interactions, and risk of colon and rectal cancers in two independent populations. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:2059–2075. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0282-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bye H, Prescott NJ, Matejcic M, Rose E, Lewis CM, Parker MI, Mathew CG. Population-specific genetic associations with oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in South Africa. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1855–1861. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY, Linsley PS, Freeman GJ, Green JM, Thompson CB, Bluestone JA. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1:405–413. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoeft B, Becker N, Deeg E, Beckmann L, Nieters A. Joint effect between regular use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, variants in inflammatory genes and risk of lymphoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:163–173. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dehaghani AS, Kashef MA, Ghaemenia M, Sarraf Z, Khaghanzadeh N, Fattahi MJ, Ghaderi A. PDCD1, CTLA-4 and p53 gene polymorphism and susceptibility to gestational trophoblastic diseases. J Reprod Med. 2009;54:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siezen CL, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Peeters PH, Kram NR, van Doeselaar M, van Kranen HJ. Polymorphisms in the genes involved in the arachidonic acid-pathway, fish consumption and the risk of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:297–303. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moatter T, Aban M, Iqbal W, Pervez S. Cyclooxygenase-2 Polymorphisms and Breast Cancer Associated Risk in Pakistani Patients. Pathol Oncol Res. 2014;21:97–101. doi: 10.1007/s12253-014-9792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niu Y, Yuan H, Shen M, Li H, Hu Y, Chen N. Association between cyclooxygenase-2 gene polymorphisms and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma risk. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:333–337. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugie S, Tsukino H, Mukai S, Akioka T, Shibata N, Nagano M, Kamoto T. Cyclooxygenase 2 genotypes influence prostate cancer susceptibility in Japanese Men. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:2717–2721. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1358-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang WS, Tsai CW, Ji HX, Wu HC, Chang YT, Lien CS, Liao WL, Shen WC, Tsai CH, Bau DT. Associations of cyclooxygenase 2 polymorphic genotypes with bladder cancer risk in Taiwan. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:5401–5405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin WG, Kim HJ, Cho SJ, Kim HS, Kim KH, Jang MK, Lee JH, Kim HY. The COX-2-1195AA Genotype Is Associated with Diffuse-Type Gastric Cancer in Korea. Gut Liver. 2012;6:321–327. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.3.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Dai L, Zhang J, Wang P, Chai Y, Ye H, Zhang J, Wang K. Cyclooxygenase-2 polymorphisms and the risk of gastric cancer in various degrees of relationship in the Chinese Han population. Oncol Lett. 2012;3:107–112. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang WS, Yang MD, Tsai CW, Cheng LH, Jeng LB, Lo WC, Lin CH, Huang CY, Bau DT. Association of cyclooxygenase 2 single-nucleotide polymorphisms and hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Chin J Physiol. 2012;55:1–7. doi: 10.4077/CJP.2012.AMM056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Ying LC, Peng HP, Zhang Jianzhi CXea. Relationship between polymorphisms in the promoter region of the COX-2 gene and susceptibility to colorectal cancer. World Chinese Journal of Digestology. 2012;20:8. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng J, Chen S, Jiang L, You Y, Wu D, Zhou Y. Functional genetic variations of cyclooxygenase-2 and susceptibility to acute myeloid leukemia in a Chinese population. Eur J Haematol. 2011;87:486–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu HC, Chang CH, Ke HL, Chang WS, Cheng HN, Lin HH, Wu CY, Tsai CW, Tsai RY, Lo WC, Bau DT. Association of cyclooxygenase 2 polymorphic genotypes with prostate cancer in taiwan. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:221–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gangwar R, Mandhani A, Mittal RD. Functional polymorphisms of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) gene and risk for urinary bladder cancer in North India. Surgery. 2011;149:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xuejiao Fan XQ, Yu HP, Zeng XY, Yang Y. Association of COX-2 gene SNPs with the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Chinese Journal of Cancer Prevention and Treatment. 2011;18:5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang CH, Wu KH, Yang YL, Peng CT, Wang RF, Tsai CW, Tsai RY, Lin DT, Tsai FJ, Bau DT. Association study of cyclooxygenase 2 single nucleotide polymorphisms and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Taiwan. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:3649–3653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mittal M, Kapoor V, Mohanti BK, Das SN. Functional variants of COX-2 and risk of tobacco-related oral squamous cell carcinoma in high-risk Asian Indians. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:622–626. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu CJ, Hsia TC, Wang RF, Tsai CW, Chu CC, Hang LW, Wang CH, Lee HZ, Tsai RY, Bau DT. Interaction of cyclooxygenase 2 genotype and smoking habit in Taiwanese lung cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:1195–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lifeng Liu JZ, Jusheng LIin. The relationship between Cyclooxygenase-2 gene -1195G/A genotype and risk of HBV-induced HCC: a case-control study in H an Chinese people. Chinese Journal of Gastroenterology Hepatology. 2010;19:3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen XB, Chen GL, Liu JN, Yang JZ, Yu DK, Lin DX, Tan W. [Genetic polymorphisms in STK15 and MMP-2 associated susceptibility to esophageal cancer in Mongolian population] . Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;43:559–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu HM, Kuo CH, Lee CH, Wu IC, Lee KW, Lee JM, Goan YG, Chou SH, Kao EL, Wu MT, Wu DC. Polymorphism in COX-2 modifies the inverse association between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma risk in Taiwan: a case control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srivastava K, Srivastava A, Pandey SN, Kumar A, Mittal B. Functional polymorphisms of the cyclooxygenase (PTGS2) gene and risk for gallbladder cancer in a North Indian population. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:774–780. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Upadhyay R, Jain M, Kumar S, Ghoshal UC, Mittal B. Functional polymorphisms of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) gene and risk for esophageal squmaous cell carcinoma. Mutat Res. 2009;663:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao D, Xu D, Zhang X, Wang L, Tan W, Guo Y, Yu D, Li H, Zhao P, Lin D. Interaction of cyclooxygenase-2 variants and smoking in pancreatic cancer: a possible role of nucleophosmin. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1659–1668. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu DK, Zhang XM, Zhao P, Cai JC, Zhao D, Tan W, Guo YL, Lin DX. [Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the promoter of cyclooxygenase COX-2 gene and hereditary susceptibility to pancreatic cancer] . Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008;88:1961–1965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chiang SL, Chen PH, Lee CH, Ko AM, Lee KW, Lin YC, Ho PS, Tu HP, Wu DC, Shieh TY, Ko YC. Up-regulation of inflammatory signalings by areca nut extract and role of cyclooxygenase-2-1195G>a polymorphism reveal risk of oral cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8489–8498. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.XU Dong-kui ZX-m, Zhao P. Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in promoter of COX-2 gene and hereditary susceptibility to hepatooellular carcinoma. Chinese Journal of Hepatobiliary Surgery. 2008;14:4. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao J, Ke Q, Ma HX, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Hu ZB, Zhai XJ, Wang XC, Qing JW, Chen WS, Jin GF, Liu JY, Tan YF, Wang XR, Shen HB. Functional polymorphisms in the cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) gene and risk of breast cancer in a Chinese population. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007;70:908–915. doi: 10.1080/15287390701289966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guojun Jiang HW, Zhou Y, Tan YF, Ding WL, et al. The correlation study between the nucleotide polymorphisms of cyclooxygenase-2 gene and the susceptibility to gastric cancer. Acta Universitatis Medicinalis Nanjing (Natural Science) 2007;27:5. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu F, Pan K, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ma J, Dong C, Shen L, Li J, Deng D, Lin D, You W. Genetic variants in cyclooxygenase-2: Expression and risk of gastric cancer and its precursors in a Chinese population. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1975–1984. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Piranda DN, Festa-Vasconcellos JS, Amaral LM, Bergmann A, Vianna-Jorge R. Polymorphisms in regulatory regions of cyclooxygenase-2 gene and breast cancer risk in Brazilians: a case-control study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:613. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson CL, Plummer SJ, Merkulova A, Cheng I, Tucker TC, Casey G, Li L. No association between cyclooxygenase-2 and uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A6 genetic polymorphisms and colon cancer risk. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2240–2244. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang ET, Birmann BM, Kasperzyk JL, Conti DV, Kraft P, Ambinder RF, Zheng T, Mueller NE. Polymorphic variation in NFKB1 and other aspirin-related genes and risk of Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:976–986. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng I, Liu X, Plummer SJ, Krumroy LM, Casey G, Witte JS. COX2 genetic variation, NSAIDs, and advanced prostate cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:557–561. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pereira C, Queiros S, Galaghar A, Sousa H, Pimentel-Nunes P, Brandao C, Moreira-Dias L, Medeiros R, Dinis-Ribeiro M. Genetic variability in key genes in prostaglandin E2 pathway (COX-2, HPGD, ABCC4 and SLCO2A1) and their involvement in colorectal cancer development. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andersen V, Holst R, Kopp TI, Tjonneland A, Vogel U. Interactions between diet, lifestyle and IL10, IL1B, and PTGS2/COX-2 gene polymorphisms in relation to risk of colorectal cancer in a prospective Danish case-cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoff JH, te Morsche RH, Roelofs HM, van der Logt EM, Nagengast FM, Peters WH. COX-2 polymorphisms -765G-->C and -1195A-->G and colorectal cancer risk. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4561–4565. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kristinsson JO, van Westerveld P, te Morsche RH, Roelofs HM, Wobbes T, Witteman BJ, Tan AC, van Oijen MG, Jansen JB, Peters WH. Cyclooxygenase-2 polymorphisms and the risk of esophageal adeno- or squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3493–3497. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moons LM, Kuipers EJ, Rygiel AM, Groothuismink AZ, Geldof H, Bode WA, Krishnadath KK, Bergman JJ, van Vliet AH, Siersema PD, Kusters JG. COX-2 CA-haplotype is a risk factor for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2373–2379. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gharib AF, Karam RA, Abd El Rahman TM, Elsawy WH. COX-2 polymorphisms -765G-->C and -1195A-->G and hepatocellular carcinoma risk. Gene. 2014;543:234–236. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akkiz H, Bayram S, Bekar A, Akgollu E, Ulger Y. Functional polymorphisms of cyclooxygenase-2 gene and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;347:201–208. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0629-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kopp TI, Friis S, Christensen J, Tjonneland A, Vogel U. Polymorphisms in genes related to inflammation, NSAID use, and the risk of prostate cancer among Danish men. Cancer Genet. 2013;206:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brasky TM, Bonner MR, Moysich KB, Ochs-Balcom HM, Marian C, Ambrosone CB, Nie J, Tao MH, Edge SB, Trevisan M, Shields PG, Freudenheim JL. Genetic variants in COX-2, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and breast cancer risk: the Western New York Exposures and Breast Cancer (WEB) Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:157–165. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1082-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Talar-Wojnarowska R, Gasiorowska A, Olakowski M, Lampe P, Smolarz B, Romanowicz-Makowska H, Malecka-Panas E. Role of cyclooxygenase-2 gene polymorphisms in pancreatic carcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4113–4117. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i36.4113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peters WH, Lacko M, Te Morsche RH, Voogd AC, Oude Ophuis MB, Manni JJ. COX-2 polymorphisms and the risk for head and neck cancer in white patients. Head Neck. 2009;31:938–943. doi: 10.1002/hed.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vogel U, Christensen J, Wallin H, Friis S, Nexo BA, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Overvad K, Tjonneland A. Polymorphisms in genes involved in the inflammatory response and interaction with NSAID use or smoking in relation to lung cancer risk in a prospective study. Mutat Res. 2008;639:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vogel U, Christensen J, Wallin H, Friis S, Nexo BA, Tjonneland A. Polymorphisms in COX-2, NSAID use and risk of basal cell carcinoma in a prospective study of Danes. Mutat Res. 2007;617:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lira MG, Mazzola S, Tessari G, Malerba G, Ortombina M, Naldi L, Remuzzi G, Boschiero L, Forni A, Rugiu C, Piaserico S, Girolomoni G, Turco A. Association of functional gene variants in the regulatory regions of COX-2 gene (PTGS2) with nonmelanoma skin cancer after organ transplantation. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Papafili A, Hill MR, Brull DJ, McAnulty RJ, Marshall RP, Humphries SE, Laurent GJ. Common promoter variant in cyclooxygenase-2 represses gene expression: evidence of role in acute-phase inflammatory response. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1631–1636. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000030340.80207.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang X, Miao X, Tan W, Ning B, Liu Z, Hong Y, Song W, Guo Y, Zhang X, Shen Y, Qiang B, Kadlubar FF, Lin D. Identification of functional genetic variants in cyclooxygenase-2 and their association with risk of esophageal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liang Y, Liu JL, Wu Y, Zhang ZY, Wu R. Cyclooxygenase-2 polymorphisms and susceptibility to esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2011;223:137–144. doi: 10.1620/tjem.223.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yan WF, Sun PC, Nie CF, Wu G. Cyclooxygenase-2 polymorphisms were associated with the risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a meta-analysis based on case-control studies. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:3323–3330. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0901-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bu X, Zhao C. The association between cyclooxygenase-2 1195 G/A polymorphism and hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence from a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:1479–1484. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]