Abstract

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) is related to inflammation and plays an important role in the development of cancer. PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism might influence the risk of cancer by regulating production of PPARG gene. Hence, a comprehensive meta-analysis was conducted to explore the association of PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism with cancer susceptibility. An extensive search of PubMed and Embase databases for all relevant publications was carried out. A total of 38 publications with 16,844 cancer cases and 23,736 controls for PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism were recruited in our study. Our results indicated that PPARG rs1801282 C>G variants were associated with an increased cancer risk in Asian populations and gastric cancer. In summary, the findings suggest that PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism may play a crucial role in malignant transformation and the development of cancer.

Keywords: Cancer, polymorphism, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, meta-analysi

Introduction

With the dramatic increase of the incidence of cancer and cancer-relative mortality, cancer has become one of the major public health burdens. For this reason, novel cancer biomarkers are needed urgently for prevention and early detection of malignance. Carcinogenesis is a very complicated process and has not been fully understood. It is believed that the development of cancer is influenced by susceptibility genes and environmental factors.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG), a type of nuclear hormone receptor, acts as an important transcriptional regulator of cellular differentiation, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism [1]. PPARG also owns certain anti-inflammatory properties [2,3]. Activation of PPARG reduces the production of multiple cytokines (e.g., interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha) by antagonizing the role of the signal transducer and activator of transcription, nuclear factor kappa-B and transcription factors activator protein 1, which suppresses induction of the inflammatory response [4,5]. Since PPARG has been supported to take part in cell growth and differentiation, it has been hypothesized that the disorder of PPARG contributes to malignant transformation and the development of cancer. The PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism, a SNP in exon 2 of PPARG, encodes a proline→alanine substitution at amino acid residue 12 (Pro12Ala). This mutation reduces the transcription of PPARγ2 [3]. The PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism has been extensively investigated and was found to be correlated with the risk of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes [6-9]. Furthermore, the evidence is mounting that PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism might affect individual susceptibility to certain types of malignancy (e.g., gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer and colorectal cancer) [10-14].

Recently, the association between this polymorphism in PPARG gene and cancer risk was extensively examined. A meta-analysis supported that PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism was associated with the increased risk of gastric cancer, but this polymorphism was not correlated with overall cancer risk [15]. Up to now, 43 publications focus on the correlation of the PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism with cancer risk, and the observed results remain conflicting. In the present study, we harnessed an updated meta-analysis on the eligible studies to further investigate the association of PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism with the risk of cancer.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Eligible publications were extracted by exhaustively electronic search of PubMed and Embase databases using the following terms: (Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma or PPARγ or PPARG) and (polymorphism or SNP or mutation or variant) and (cancer or carcinoma or malignance). References of retrieved studies, comments, meta-analyses, reviews and letters were manually searched for additional publications. There was no limitation of language and the last research was performed on July 15, 2014.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were defined as follows: (a) The publications assessed the association of PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism with cancer risk; (b) The studies designed as a case-control or cohort study; (c) The sufficient data could be extracted to calculate an odds ratio (OR) with its 95% CI; (d) In these articles, the genotype distributions among controls were consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). The major exclusion criteria were: (a) not a case-control or cohort study; (b) overlapping data; (c) comments, letters, reviews, animal studies and editorials; (d) cancer prognosis and treatment. In certain publications, the data were reported on different subgroups; we treated them as separate studies.

Data extraction

From each eligible study, data were extracted independently by three authors (Y. Wang, Y. Chen and H. Jiang). The following terms were collected: the surname of first author, year of publication, country, numbers of subjects and genotype frequencies of cases and controls, cancer type, ethnicity, genotyping method, and evidence of HWE in controls. If there were any discrepancies, they were resolved following a discussion between all reviewers.

Statistical analysis

HWE in controls was tested by a web-based Pearson’s χ2 test (http://ihg.gsf.de/cgi-bin/hw/hwa1.pl). We used crude ORs with corresponding 95% CIs as an assessment of the association between PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism with cancer risk. A P<0.05 was considered significant. Heterogeneities were assessed using Cochran’s Q-statistic and I2 test. When I2>50% or P<0.10, there was significant heterogeneity, then the random-effects model was applied [16], otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used [17]. Subgroup analyses were conducted by ethnicity and cancer type. Sensitivity analysis was performed by nonparametric “trim-and-fill” method. The Begg’s test and Egger’s test were both used to determine the evidence of publication bias [18]. For publication bias test, statistical significance was defined as P<0.1. In our study, all the statistical analyses were conducted with Stata 12.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and P values were two-sided.

Results

Characteristics of studies

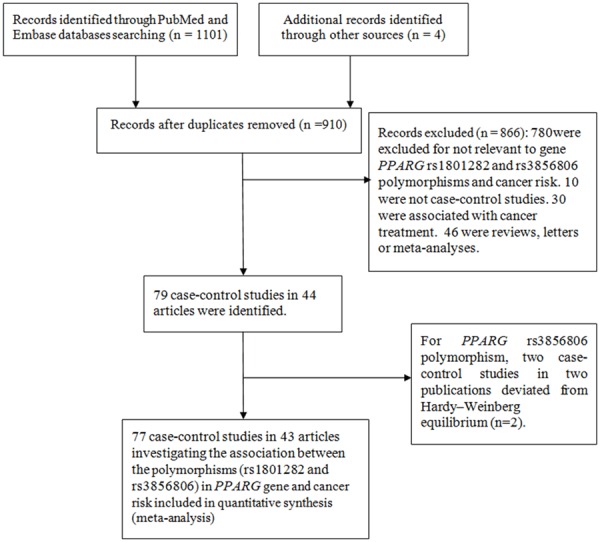

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 1101 publications were retrieved. According to the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, there were 38 publications (including 51 individual studies) on the PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism [10,11,13,14,19-52]. Among them, fifteen investigated colorectal cancer [13,14,19-28], seven investigated breast cancer [12,29-33,35], five investigated ovarian cancer [36,37], five investigated gastric cancer [10,38-41], four investigated lung cancer [42-45], four investigated prostate cancer [37,46-48], two investigated pancreatic cancer [11,49], two investigated melanoma [50] and two investigated glioblastoma [51]. Other articles investigated skin cancer [52], endometrial cancer [37], bladder cancer [37], cervical cancer [37] and renal cell carcinoma [37]. Among these, 28 were from Caucasians, 12 were from Asians and 11 were from mixed populations. The characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The genotype distributions are listed in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included and excluded process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of all included studies in the meta-analysis

| study | Publication year | Ethnicity | Country | Cancer type | Sample size (case/control) | Genotype method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kopp et al. | 2013 | Caucasians | Denmark | prostate cancer | 370/370 | RT-PCR |

| Martinez-Nava et al. | 2013 | mixed | Mexico | breast cancer | 208/220 | RT-PCR |

| Canbay et al. | 2012 | Caucasians | Turkey | gastric cancer | 86/129 | PCR-RFLP |

| Crous-Bou et al. | 2012 | Caucasians | Israel | colorectal cancer | 1780/1864 | Illumina Beadstation and BeadExpress |

| Petersen et al. | 2012 | Caucasians | Denmark | breast cancer | 798/798 | TaqMan |

| Abuli et al. | 2011 | Caucasians | Spain | colorectal cancer | 515/502 | MALDI-TOF MS |

| Tang et al. | 2011 | mixed | USA | pancreatic cancer | 1070/1175 | TaqMan |

| Lim et al. | 2011 | Asians | Singapore | lung cancer | 298/718 | RT-PCR |

| Wu et al. | 2011 | Asians | China | breast cancer | 291/589 | RT-PCR |

| Bazargani et al. | 2010 | Caucasians | Iran | gastric cancer | 79/152 | PCR–RFLP |

| Pinheiro et al. | 2010 | Caucasians | UK | ovarian cancer | 233/663 | Taqman |

| Pinheiro et al. | 2010 | Caucasians | UK | ovarian cancer | 1120/1160 | Taqman |

| Tsilidis et al. | 2009 | mixed | USA | colorectal cancer | 208/381 | Taqman |

| Fesinmeyer et al. | 2009 | mixed | USA | pancreatic cancer | 83/166 | TaqMan |

| Wang et al. | 2009 | mixed | USA | prostate cancer | 258/258 | TaqMan |

| Kury et al. | 2008 | Caucasians | France | colorectal cancer | 1023/1121 | TaqMan |

| Prasad et al. | 2008 | Asians | India | gastric cancer | 62/286 | PCR-RFLP |

| Tahara et al. | 2008 | Asians | Japan | gastric cancer | 215/201 | PCR-RFLP |

| Vogel et al. | 2008 | Caucasians | Denmark | lung cancer | 403/744 | TaqMan |

| Justenhoven et al. | 2008 | Caucasians | German | breast cancer | 688/724 | MALDI-TOF MS |

| Gallicchio et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | USA | breast cancer | 61/933 | TaqMan |

| Wang et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | USA | breast cancer | 488/488 | TaqMan |

| Mossner et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | German | melanoma | 335/355 | PCR-RFLP |

| Mossner et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | German | melanoma | 497/435 | PCR-RFLP |

| Vogel et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | Denmark | colorectal cancer | 355/753 | TaqMan |

| Zhang et al. | 2007 | Asians | China | lung cancer | 45/45 | DNA sequence |

| Vogel et al. | 2007 | Caucasians | Denmark | skin cancer | 304/315 | TaqMan |

| Kuriki et al. | 2006 | Asians | Japan | colorectal cancer | 128/238 | PCR-CTPP, PCR-RFLP |

| Theodoropoulos et al. | 2006 | Caucasians | Greece | colorectal cancer | 222/200 | PCR-RFLP |

| Liao et al. | 2006 | Asians | China | gastric cancer | 104/104 | PCR-RFLP |

| Siezen et al. | 2006 | Caucasians | The netherlands | colorectal cancer | 204/399 | DNA sequence |

| Siezen et al. | 2006 | Caucasians | The netherlands | colorectal cancer | 487/750 | DNA sequence |

| Slattery et al. | 2005 | mixed | USA | colorectal cancer | 2371/2972 | TaqMan |

| McGreavey et al. | 2005 | Caucasians | UK | colorectal cancer | 478/733 | TaqMan |

| Jiang et al. | 2005 | Asians | India | colorectal cancer | 59/291 | PCR-RFLP |

| Jiang et al. | 2005 | Asians | India | colorectal cancer | 242/291 | PCR-RFLP |

| Campa et al. | 2004 | Caucasians | Norway | lung cancer | 250/214 | TaqMan |

| Landi et al. | 2003 | Caucasians | Spain | colorectal cancer | 139/326 | TaqMan |

| Landi et al. | 2003 | Caucasians | Spain | colorectal cancer | 238/326 | TaqMan |

| Paltoo et al. | 2003 | Caucasians | Finland | prostate cancer | 193/188 | MALDI-TOF |

| Memisoglu et al. | 2002 | mixed | USA | breast cancer | 725/953 | PCR-RFLP |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | Caucasians | UK | Renal cell carcinoma | 40/62 | DGGE |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | Caucasians | UK | ovarian cancer | 31/62 | DGGE |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | Asians | Japan | ovarian cancer | 28/215 | DGGE |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | Asians | Japan | cervical cancer | 20/215 | DGGE |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | Asians | Japan | bladder cancer | 31/215 | DGGE |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | mixed | USA | ovarian cancer | 26/80 | DGGE |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | mixed | USA | endometrial cancer | 69/80 | DGGE |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | mixed | USA | prostate cancer | 38/80 | DGGE |

| Zhou et al. | 2000 | mixed | USA | glioblastoma | 52/80 | PCR |

| Zhou et al. | 2000 | Caucasians | German | glioblastoma | 44/60 | PCR |

RT-PCR: reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction. MALDI-TOF MS: Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry. PCR-RFLP: polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism. PCR-CTPP: polymerase chain reaction with confronting two-pair primers. DGGE: denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis.

Table 2.

Distribution of PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism genotype and allele among cases and controls

| Study | Publication year | Case | Control | Case | Control | HWE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| CC | CG | GG | CC | CG | GG | G | C | G | C | |||

| Kopp et al. | 2013 | 241 | 90 | 3 | 245 | 87 | 2 | 96 | 572 | 91 | 577 | 0.050905 |

| Martı´nez-Nava et al. | 2013 | 165 | 43 | 0 | 169 | 49 | 2 | 43 | 373 | 53 | 387 | 0.448105 |

| Canbay et al. | 2012 | 68 | 14 | 4 | 116 | 12 | 1 | 22 | 150 | 14 | 244 | 0.287345 |

| Crous-Bou et al. | 2012 | 710 | 102 | 0 | 1307 | 163 | 9 | 102 | 1522 | 181 | 2777 | 0.117069 |

| Petersen et al. | 2012 | 616 | 167 | 15 | 569 | 209 | 20 | 197 | 1399 | 249 | 1347 | 0.87691 |

| Abuli et al. | 2011 | 426 | 87 | 2 | 419 | 80 | 3 | 91 | 939 | 86 | 918 | 0.697001 |

| Tang et al. | 2011 | 826 | 216 | 10 | 871 | 236 | 23 | 236 | 1868 | 282 | 1978 | 0.140851 |

| Lim et al. | 2011 | 274 | 23 | 1 | 653 | 64 | 1 | 25 | 571 | 66 | 1370 | 0.660099 |

| Wu et al. | 2011 | 260 | 29 | 0 | 546 | 40 | 0 | 29 | 549 | 40 | 1132 | 0.392337 |

| Bazargani et al. | 2010 | 60 | 18 | 1 | 134 | 17 | 1 | 20 | 138 | 19 | 285 | 0.573866 |

| Pinheiro et al. | 2010 | 166 | 56 | 2 | 487 | 144 | 13 | 60 | 388 | 170 | 1118 | 0.540142 |

| Pinheiro et al. | 2010 | 831 | 228 | 16 | 882 | 241 | 13 | 260 | 1890 | 267 | 2005 | 0.441786 |

| Tsilidis et al. | 2009 | 165 | 37 | 1 | 295 | 68 | 6 | 39 | 367 | 80 | 658 | 0.370123 |

| Fesinmeyer et al. | 2009 | 60 | 22 | 1 | 139 | 27 | 0 | 24 | 142 | 27 | 305 | 0.254053 |

| Wang et al. | 2009 | 198 | 57 | 0 | 189 | 58 | 7 | 57 | 453 | 72 | 436 | 0.327667 |

| Kury et al. | 2008 | 822 | 194 | 7 | 896 | 212 | 13 | 208 | 1838 | 238 | 2004 | 0.9079 |

| Prasad et al. | 2008 | 39 | 18 | 5 | 214 | 67 | 5 | 28 | 96 | 77 | 495 | 0.926116 |

| Tahara et al. | 2008 | 194 | 21 | 0 | 193 | 8 | 0 | 21 | 409 | 8 | 394 | 0.773449 |

| Vogel et al. | 2008 | 301 | 93 | 9 | 544 | 187 | 13 | 111 | 695 | 213 | 1275 | 0.502205 |

| Justenhoven et al. | 2008 | 452 | 135 | 6 | 462 | 145 | 15 | 147 | 1039 | 175 | 1069 | 0.372101 |

| Gallicchio et al. | 2007 | 48 | 7 | 1 | 689 | 188 | 18 | 9 | 103 | 224 | 1566 | 0.223793 |

| Wang et al. | 2007 | 376 | 87 | 15 | 375 | 98 | 5 | 117 | 839 | 108 | 848 | 0.615475 |

| Mossner et al. | 2007 | 239 | 84 | 11 | 258 | 86 | 7 | 106 | 562 | 100 | 602 | 0.957311 |

| Mossner et al. | 2007 | 372 | 115 | 7 | 324 | 102 | 6 | 129 | 859 | 114 | 750 | 0.522918 |

| Vogel et al. | 2007 | 252 | 96 | 7 | 550 | 190 | 13 | 110 | 600 | 216 | 1290 | 0.460144 |

| Zhang et al. | 2007 | 39 | 6 | 0 | 41 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 84 | 4 | 86 | 0.755033 |

| Vogel et al. | 2007 | 220 | 83 | 1 | 232 | 77 | 6 | 85 | 523 | 89 | 541 | 0.894139 |

| Kuriki et al. | 2006 | 120 | 7 | 0 | 221 | 17 | 0 | 7 | 247 | 17 | 459 | 0.567742 |

| Theodoropoulos et al. | 2006 | 164 | 48 | 10 | 118 | 70 | 12 | 68 | 376 | 94 | 306 | 0.707193 |

| Liao et al. | 2006 | 84 | 17 | 3 | 95 | 9 | 0 | 23 | 185 | 9 | 199 | 0.644642 |

| Siezen et al. | 2006 | 160 | 40 | 1 | 325 | 70 | 2 | 42 | 360 | 74 | 720 | 0.389723 |

| Siezen et al. | 2006 | 387 | 92 | 8 | 596 | 146 | 8 | 108 | 866 | 162 | 1338 | 0.723797 |

| Slattery et al. | 2005 | 1840 | 496 | 35 | 2283 | 645 | 44 | 566 | 4176 | 733 | 5211 | 0.839204 |

| McGreavey et al. | 2005 | 366 | 80 | 9 | 403 | 100 | 10 | 98 | 812 | 120 | 906 | 0.202319 |

| Jiang et al. | 2005 | 46 | 13 | 0 | 230 | 57 | 4 | 13 | 105 | 65 | 517 | 0.768946 |

| Jiang et al. | 2005 | 194 | 44 | 4 | 230 | 57 | 4 | 52 | 432 | 65 | 517 | 0.768946 |

| Campa et al. | 2004 | 2 | 52 | 192 | 4 | 47 | 161 | 436 | 56 | 369 | 55 | 0.792322 |

| Landi et al. | 2003 | 111 | 15 | 3 | 243 | 61 | 5 | 21 | 237 | 71 | 547 | 0.60618 |

| Landi et al. | 2003 | 200 | 31 | 0 | 243 | 61 | 5 | 31 | 431 | 71 | 547 | 0.60618 |

| Paltoo et al. | 2003 | 121 | 64 | 8 | 128 | 54 | 6 | 80 | 306 | 66 | 310 | 0.916738 |

| Memisoglu et al. | 2002 | 563 | 148 | 14 | 752 | 190 | 11 | 176 | 1274 | 212 | 1694 | 0.795703 |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | 37 | 3 | 0 | 49 | 11 | 2 | 3 | 77 | 15 | 109 | 0.191855 |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | 27 | 4 | 0 | 49 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 58 | 15 | 109 | 0.191855 |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | 27 | 1 | 0 | 203 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 55 | 13 | 417 | 0.061618 |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 203 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 39 | 13 | 417 | 0.061618 |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | 29 | 2 | 0 | 203 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 60 | 13 | 417 | 0.061618 |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | 21 | 5 | 0 | 68 | 12 | 0 | 5 | 47 | 12 | 148 | 0.468322 |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | 56 | 13 | 0 | 68 | 12 | 0 | 13 | 125 | 12 | 148 | 0.468322 |

| Smith et al. | 2001 | 34 | 4 | 0 | 68 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 72 | 12 | 148 | 0.468322 |

| Zhou et al. | 2000 | 37 | 15 | 0 | 68 | 12 | 0 | 15 | 89 | 12 | 148 | 0.468322 |

| Zhou et al. | 2000 | 35 | 9 | 0 | 46 | 14 | 0 | 9 | 79 | 14 | 106 | 0.306283 |

HWE: Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

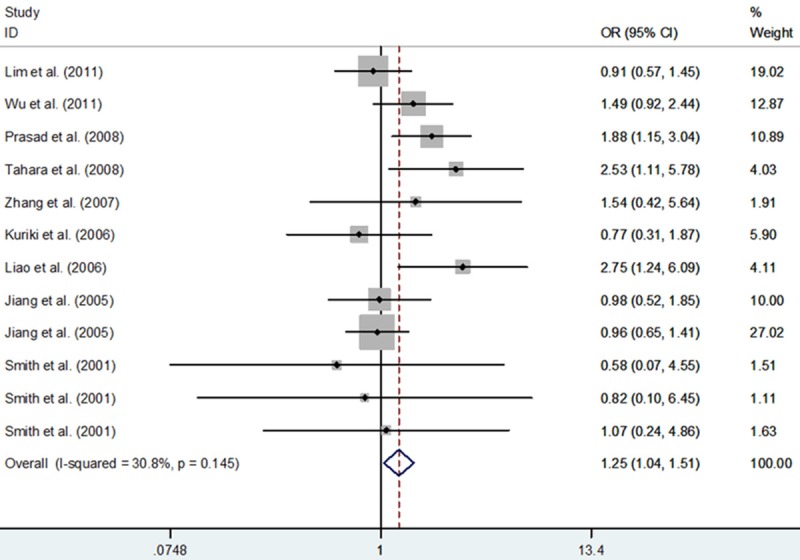

Quantitative synthesis

In total, 51 studies with 16,844 cancer cases and 23,736 controls focused on the relationship of PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism with cancer risk. Overall, our results did not support any statistical evidence of the association between PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism and cancer. As Caucasians, Asians and mixed populations were involved in our study, we performed subgroup analyses base on different ethnicities. The results showed that PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism was a risk factor for cancer in Asians: GG+CG vs. CC (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.01-1.50; P = 0.039), GG vs. CG+CC (OR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.15-4.86; P = 0.020), GG vs. CC (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.18-5.01; P = 0.016) and G vs. C (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.04-1.51; P = 0.018) (Table 3; Figure 2). With respect to a subgroup analysis by cancer type, the results of the combined analyses showed that PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism was associated with gastric cancer risk in five genetic models: GG+CG vs. CC (OR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.61-3.07; P<0.001), GG vs. CG+CC (OR, 4.95; 95% CI, 1.86-13.16; P = 0.001), GG vs. CC (OR, 5.51; 95% CI, 2.06-14.79; P = 0.001), CG vs. CC (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.44-2.82; P<0.001) and G vs. C (OR, 2.26; 95% CI, 1.69-3.02; P<0.001) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Different comparative genetic models results of this meta-analysis in the subgroup analysis by race

| Polymorphism | Genetic comparison | Population | OR (95% CI); P | Test of heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| (p-Value, I2) | Model | ||||

| rs1801282 C>G | GG+CG vs. CC | All | 1.00 (0.93-1.07); 0.987 | 0.007, 35.7% | R |

| Asians | 1.23 (1.01-1.50); 0.039 | 0.272, 17.6% | F | ||

| Caucasians | 0.96 (0.88-1.05); 0.402 | 0.009, 43.2% | R | ||

| Mixed | 0.98 (0.90-1.07); 0.656 | 0.305, 14.6% | F | ||

| GG vs. CG+CC | All | 0.97 (0.83-1.14); 0.713 | 0.175, 16.8% | F | |

| Asians | 2.36 (1.15-4.86); 0.020 | 0.808, 0.0% | F | ||

| Caucasians | 0.98 (0.80-1.18); 0.800 | 0.415, 3.3% | F | ||

| Mixed | 0.76 (0.39-1.45); 0.399 | 0.055, 51.4% | R | ||

| GG vs. CC | All | 0.94 (0.79-1.12); 0.511 | 0.101, 22.5% | F | |

| Asians | 2.43 (1.18-5.01); 0.016 | 0.785, 0.0% | F | ||

| Caucasians | 0.94 (0.75-1.16); 0.543 | 0.302, 11.0% | F | ||

| Mixed | 0.75 (0.39-1.46); 0.399 | 0.049, 52.6% | R | ||

| CG vs. CC | All | 1.00 (0.93-1.07); 0.956 | 0.047, 26.3% | R | |

| Asians | 1.20 (0.98-1.47); 0.083 | 0.439, 0.5% | F | ||

| Caucasians | 0.96 (0.88-1.05); 0.402 | 0.023, 37.9% | R | ||

| Mixed | 0.99 (0.91-1.09); 0.870 | 0.488, 0.0% | F | ||

| G vs. C | All | 1.00 (0.94-1.07); 0.952 | 0.001, 42.3% | R | |

| Asians | 1.25 (1.04-1.51); 0.018 | 0.145, 30.8% | F | ||

| Caucasians | 0.97 (0.89-1.05); 0.466 | 0.005, 45.6% | R | ||

| Mixed | 0.97 (0.89-1.05); 0.459 | 0.158, 30.3% | F | ||

F indicates fixed model; R indicates random model.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis with a fixed-effect for the association of cancer risk with the PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism in Asians (allele comparing model).

Table 4.

Different comparative genetic models results of this meta-analysis in the subgroup analysis by cancer type

| Polymorphism | Genetic comparison | Cancer type | OR (95% CI); P | Test of heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| (p-Value, I2) | Model | ||||

| rs1801282 C>G | GG+CG vs. CC | All | 1.00 (0.93-1.07); 0.987 | 0.007, 35.7% | R |

| Prostate cancer | 1.02 (0.82-1.27); 0.836 | 0.482, 0.0% | F | ||

| Breast cancer | 0.93 (0.78-1.10); 0.395 | 0.076, 47.5% | R | ||

| Gastric cancer | 2.22 (1.61-3.07); <0.001 | 0.922, 0.0% | F | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 0.94 (0.87-1.02); 0.131 | 0.125, 30.6% | F | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.27 (0.61-2.65); 0.529 | 0.024, 80.2% | R | ||

| Lung cancer | 0.95 (0.75-1.19); 0.636 | 0.623, 0.0% | F | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 1.02 (0.86-1.21); 0.792 | 0.828, 0.0% | F | ||

| Melanoma | 1.03 (0.83-1.29); 0.764 | 0.619, 0.0% | F | ||

| Glioblastoma | 1.42 (0.53-3.79); 0.481 | 0.125, 57.6% | R | ||

| Other cancers | 1.01 (0.74-1.37); 0.968 | 0.459, 0.0% | F | ||

| GG vs. CG+CC | All | 0.97 (0.83-1.14); 0.713 | 0.175, 16.8% | F | |

| Prostate cancer | 0.76 (0.16-3.58); 0.726 | 0.104, 55.8% | R | ||

| Breast cancer | 1.00 (0.51-1.98); 0.991 | 0.045, 55.9% | R | ||

| Gastric cancer | 4.95 (1.86-13.16); 0.001 | 0.910, 0.0% | F | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 0.86 (0.65-1.12); 0.258 | 0.770, 0.0% | F | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.02 (0.10-10.55); 0.985 | 0.126, 57.4% | R | ||

| Lung cancer | 1.17 (0.80-1.72); 0.420 | 0.845, 0.0% | F | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 0.98 (0.53-1.80); 0.946 | 0.497, 0.0% | F | ||

| Melanoma | 1.35 (0.66-2.78); 0.409 | 0.506, 0.0% | F | ||

| Glioblastoma | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Other cancers | 0.40 (0.10-1.51); 0.174 | 0.319, 14.5% | F | ||

| GG vs. CC | All | 0.94 (0.79-1.12); 0.511 | 0.101, 22.5% | F | |

| Prostate cancer | 0.77 (0.16-3.81); 0.752 | 0.094, 57.7% | R | ||

| Breast cancer | 0.97 (0.49-1.93); 0.930 | 0.039, 57.2% | R | ||

| Gastric cancer | 5.51 (2.06-14.79); 0.001 | 0.920, 0.0% | F | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 0.83 (0.63-1.09); 0.183 | 0.729, 0.0% | F | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.12 (0.09-13.61); 0.931 | 0.107, 61.6% | R | ||

| Lung cancer | 1.49 (0.72-3.09); 0.287 | 0.756, 0.0% | F | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 0.98 (0.54-1.81); 0.960 | 0.507, 0.0% | F | ||

| Melanoma | 1.36 (0.66-2.80); 0.402 | 0.492, 0.0% | F | ||

| Glioblastoma | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Other cancers | 0.39 (0.10-1.50); 0.172 | 0.319, 14.6% | F | ||

| CG vs. CC | All | 1.00 (0.93-1.07); 0.956 | 0.047, 26.3% | R | |

| Prostate cancer | 1.05 (0.84-1.31); 0.684 | 0.693, 0.0% | F | ||

| Breast cancer | 0.91 (0.80-1.02); 0.108 | 0.118, 40.9% | F | ||

| Gastric cancer | 2.01 (1.44-2.82); <0.001 | 0.820, 0.0% | F | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 0.95 (0.88-1.03); 0.207 | 0.113, 32.0% | F | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.26 (0.66-2.39); 0.485 | 0.050, 73.9% | R | ||

| Lung cancer | 0.92 (0.73-1.17); 0.507 | 0.637, 0.0% | F | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 1.03 (0.87-1.22); 0.747 | 0.872, 0.0% | F | ||

| Melanoma | 1.01 (0.80-1.27); 0.914 | 0.763, 0.0% | F | ||

| Glioblastoma | 1.42 (0.53-3.79); 0.481 | 0.125, 57.6% | R | ||

| Other cancers | 1.08 (0.79-1.47); 0.642 | 0.578, 0.0% | F | ||

| G vs. C | All | 1.00 (0.94-1.07); 0.952 | 0.001, 42.3% | R | |

| Prostate cancer | 1.00 (0.82-1.21); 0.981 | 0.278, 22.1% | F | ||

| Breast cancer | 0.94 (0.80-1.12); 0.515 | 0.040, 54.5% | R | ||

| Gastric cancer | 2.26 (1.69-3.02); <0.001 | 0.909, 0.0% | F | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 0.94 (0.88-1.01); 0.091 | 0.195, 23.4% | F | ||

| Pancreatic cancer | 1.23 (0.59-2.60); 0.580 | 0.014, 83.4% | R | ||

| Lung cancer | 1.00 (0.83-1.21); 0.993 | 0.743, 0.0% | F | ||

| Ovarian cancer | 1.01 (0.87-1.18); 0.857 | 0.739, 0.0% | F | ||

| Melanoma | 1.05 (0.86-1.29); 0.616 | 0.497, 0.0% | F | ||

| Glioblastoma | 1.37 (0.58-3.23); 0.477 | 0.150, 51.8% | R | ||

| Other cancers | 0.94 (0.71-1.24); 0.652 | 0.392, 2.5% | F | ||

F indicates fixed model; R indicates random model.

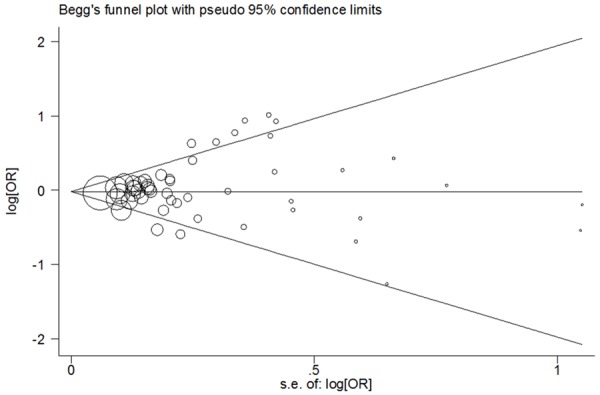

Tests for publication bias

We used Begg’s Funnel plot and Egger’s test to examine publication bias of included studies. No statistical evidence of publication bias was identified in all genetic models (G vs. C: Begg’s test P = 0.709, Egger’s test P = 0.202; GG vs. CC: Begg’s test P = 0.879, Egger’s test P = 0.935; CG vs. CC: Begg’s test P = 0.372, Egger’s test P = 0.168; GG+CG vs. CC: Begg’s test P = 0.380, Egger’s test P = 0.157; GG vs. CG+CC: Begg’s test P = 1.000, Egger’s test P = 0.676; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

For PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism, Begg’s funnel plot analysis for publication bias (allele comparing model).

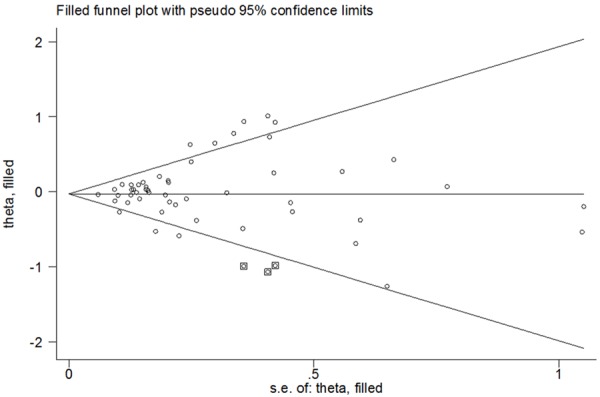

Sensitivity analyses

Influence of the potential publication bias involved in the meta-analysis on the pooled ORs and CIs was assessed by non-parametric “trim-and-fill” method and the filling of any potential studies did not significantly altered the final decision, suggesting that our results were stable and statistically robust: GG+CG vs. CC (adjusted pooled OR, 0.971; 95% CI, 0.897-1.051; P = 0.464), GG vs. CG+CC (adjusted pooled OR, 1.025; 95% CI, 0.865-1.213; P = 0.779), GG vs. CC (adjusted pooled OR, 1.002; 95% CI, 0.835-1.203; P = 0.982), CG vs. CC (adjusted pooled OR, 0.975; 95% CI, 0.905-1.051; P = 0.506) and G vs. C (adjusted pooled OR, 0.982; 95% CI, 0.911-1.059; P = 0.641) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

For PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism, Filled funnel plot of meta-analysis (allele comparing model).

Tests for heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed by the χ2-based Q-test in overall genetic models and sub-group analyses. We explored the main source of heterogeneity in sub-group analyses of ethnicity and cancer type. In current study, Caucasians, mixed populations, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer and prostate cancer provided potential sources of heterogeneity.

Discussion

The PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism has been popularly examined on the risk of many cancers; however, the results of such studies are inconsistent. To address the gap, we performed an updated meta-analysis of published studies. The results indicated that PPARG rs1801282 C>G was not associated with the risk of overall cancer. The results from our sub-group analyses suggested that there was an effective modification of the cancer risk among Asians and gastric cancer patients.

Accumulating evidences demonstrated that the PPARG gene is related to malignance, which plays an important role in the pathogenesis of multiple cancers in some clinical studies and animal models. The association between PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism and cancer risk has been widely explored. The prior study reported that PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism was associated with reduced transactivation activity, lower body mass index and improved insulin sensitivity among middle-aged and elderly Caucasians [3]. PPARG gene variants may increase susceptibility of colorectal cancer by interruption of the metabolism of a high fat diet [53]. In the current study, a significantly increased risk of cancer correlated with PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism was overt among Asians and gastric cancer patients. Our results suggest different cancerigenic mechanisms of different cancers and different population. A previous meta-analysis was performed to determine the effect of PPARG polymorphisms on the risk of cancer [15]. Comparing with that, our pooled analyses have some merits. First, this is a larger samples meta-analysis not only to analyze the association between PPARG rs1801282 C>G and cancer susceptibility in different races and different cancer types, but also to support the rs1801282 C>G polymorphism is a risk factor in Asians and gastric cancer. Second, we carried out a more extensively pooled analysis by calculating five different comparison models and performing sub-group analyses.

Since heterogeneity across studies may affect the strengths of results, we conducted sub-group analyses. In our study, relatively high heterogeneity was observed. Then, the random-effect model was utilized when significant heterogeneity was found. Meanwhile, to analyze the major source of heterogeneity, we conducted sub-group analyses by races and cancer types. Results of meta-analysis showed that heterogeneity greatly reduced or vanished in some sub-groups. We also performed non-parametric “trim-and-fill” method to verify the stability of our results. The adjusted ORs and CIs were not materially altered, suggesting that the results of our study were reliable and suggestive. The publication bias across studies for the correlation of PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism with cancer risk was not observed.

Some limitations should be noted in this meta-analysis when interpreting the results. First of all, only published literatures were included in our study, some unpublished investigations that might also be fit for the inclusion criteria were ignored. Secondly, due to limited individual data (e.g., age, sex and other environmental factors) in some studies, we did not perform a more precise analysis, which limited further assessments to a certain extent. Finally, in some subgroups, sample sizes were relatively small, which might have insufficient power to get a reliable result. In the future, studies with larger sample sizes will be needed to validate these associations.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that PPARG rs1801282 C>G polymorphism is a candidate for susceptibility to gastric cancer and Asians. Further studies with larger samples and detailed environmental factors will be needed to confirm our results.

Acknowledgements

Grant support: The project was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant No. 2014J01298 and 2015J01435), the Medical Innovation Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant No. 2015-CX-9) and the National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Program.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Cho MC, Lee K, Paik SG, Yoon DY. Peroxisome Proliferators-Activated Receptor (PPAR) Modulators and Metabolic Disorders. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:679137. doi: 10.1155/2008/679137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robbins GT, Nie D. PPAR gamma, bioactive lipids, and cancer progression. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:1816–1834. doi: 10.2741/4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deeb SS, Fajas L, Nemoto M, Pihlajamaki J, Mykkanen L, Kuusisto J, Laakso M, Fujimoto W, Auwerx J. A Pro12Ala substitution in PPARgamma2 associated with decreased receptor activity, lower body mass index and improved insulin sensitivity. Nat Genet. 1998;20:284–287. doi: 10.1038/3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satoh T, Toyoda M, Hoshino H, Monden T, Yamada M, Shimizu H, Miyamoto K, Mori M. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma stimulates the growth arrest and DNA-damage inducible 153 gene in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:2171–2180. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutter S, Knabl J, Andergassen U, Jeschke U. The Role of PPARs in Placental Immunology: A Systematic Review of the Literature. PPAR Res. 2013;2013:970276. doi: 10.1155/2013/970276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Liu J, Ouyang Y, Fang M, Gao H, Liu L. The association between the Pro12Ala variant in the PPARgamma2 gene and type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity in a Chinese population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Dai L, Zhang J, Wang P, Chai Y, Ye H, Zhang J, Wang K. Cyclooxygenase-2 polymorphisms and the risk of gastric cancer in various degrees of relationship in the Chinese Han population. Oncol Lett. 2012;3:107–112. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Youssef SM, Mohamed N, Afef S, Khaldoun BH, Fadoua N, Fadhel NM, Naceur SM. A Pro 12 Ala substitution in the PPARgamma2 polymorphism may decrease the number of diseased vessels and the severity of angiographic coronary artery. Coron Artery Dis. 2013;24:347–351. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328361a95e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lwow F, Dunajska K, Milewicz A, Laczmanski L, Jedrzejuk D, Trzmiel-Bira A, Szmigiero L. ADRB3 and PPARgamma2 gene polymorphisms and their association with cardiovascular disease risk in postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2013;16:473–478. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2012.738721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canbay E, Kurnaz O, Canbay B, Bugra D, Cakmakoglu B, Bulut T, Yamaner S, Sokucu N, Buyukuncu Y, Yilmaz-Aydogan H. PPAR-gamma Pro12Ala polymorphism and gastric cancer risk in a Turkish population. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5875–5878. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.11.5875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fesinmeyer MD, Stanford JL, Brentnall TA, Mandelson MT, Farin FM, Srinouanprachanh S, Afsharinejad Z, Goodman GE, Barnett MJ, Austin MA. Association between the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma Pro12Ala variant and haplotype and pancreatic cancer in a high-risk cohort of smokers: a pilot study. Pancreas. 2009;38:631–637. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181a53ef9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen RK, Larsen SB, Jensen DM, Christensen J, Olsen A, Loft S, Nellemann C, Overvad K, Kristiansen K, Tjonneland A, Vogel U. PPARgamma-PGC-1alpha activity is determinant of alcohol related breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2012;315:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landi S, Moreno V, Gioia-Patricola L, Guino E, Navarro M, de Oca J, Capella G Bellvitge Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Association of common polymorphisms in inflammatory genes interleukin (IL)6, IL8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, NFKB1, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3560–3566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theodoropoulos G, Papaconstantinou I, Felekouras E, Nikiteas N, Karakitsos P, Panoussopoulos D, Lazaris A, Patsouris E, Bramis J, Gazouli M. Relation between common polymorphisms in genes related to inflammatory response and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5037–5043. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i31.5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu W, Li Y, Wang X, Chen B, Liu S, Wang Y, Zhao W, Wu J. PPARgamma polymorphisms and cancer risk: a meta-analysis involving 32,138 subjects. Oncol Rep. 2010;24:579–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hua Z, Li D, Xiang G, Xu F, Jie G, Fu Z, Jie Z, Da P, Li D. PD-1 polymorphisms are associated with sporadic breast cancer in Chinese Han population of Northeast China. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:195–201. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayram S, Akkiz H, Ulger Y, Bekar A, Akgollu E, Yildirim S. Lack of an association of programmed cell death-1 PD1.3 polymorphism with risk of hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility in Turkish population: a case-control study. Gene. 2012;511:308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.09.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crous-Bou M, Rennert G, Salazar R, Rodriguez-Moranta F, Rennert HS, Lejbkowicz F, Kopelovich L, Lipkin SM, Gruber SB, Moreno V. Genetic polymorphisms in fatty acid metabolism genes and colorectal cancer. Mutagenesis. 2012;27:169–176. doi: 10.1093/mutage/ger066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abuli A, Fernandez-Rozadilla C, Alonso-Espinaco V, Munoz J, Gonzalo V, Bessa X, Gonzalez D, Clofent J, Cubiella J, Morillas JD, Rigau J, Latorre M, Fernandez-Banares F, Pena E, Riestra S, Paya A, Jover R, Xicola RM, Llor X, Carvajal-Carmona L, Villanueva CM, Moreno V, Pique JM, Carracedo A, Castells A, Andreu M, Ruiz-Ponte C, Castellvi-Bel S Gastrointestinal Oncology Group of the Spanish Gastroenterological Association. Case-control study for colorectal cancer genetic susceptibility in EPICOLON: previously identified variants and mucins. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:339. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsilidis KK, Helzlsouer KJ, Smith MW, Grinberg V, Hoffman-Bolton J, Clipp SL, Visvanathan K, Platz EA. Association of common polymorphisms in IL10, and in other genes related to inflammatory response and obesity with colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1739–1751. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9427-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kury S, Buecher B, Robiou-du-Pont S, Scoul C, Colman H, Le Neel T, Le Houerou C, Faroux R, Ollivry J, Lafraise B, Chupin LD, Sebille V, Bezieau S. Low-penetrance alleles predisposing to sporadic colorectal cancers: a French case-controlled genetic association study. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:326. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuriki K, Hirose K, Matsuo K, Wakai K, Ito H, Kanemitsu Y, Hirai T, Kato T, Hamajima N, Takezaki T, Suzuki T, Saito T, Tanaka R, Tajima K. Meat, milk, saturated fatty acids, the Pro12Ala and C161T polymorphisms of the PPARgamma gene and colorectal cancer risk in Japanese. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:1226–1235. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slattery ML, Curtin K, Wolff R, Ma KN, Sweeney C, Murtaugh M, Potter JD, Levin TR, Samowitz W. PPARgamma and colon and rectal cancer: associations with specific tumor mutations, aspirin, ibuprofen and insulin-related genes (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:239–249. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0411-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGreavey LE, Turner F, Smith G, Boylan K, Timothy Bishop D, Forman D, Roland Wolf C, Barrett JH Colorectal Cancer Study Group. No evidence that polymorphisms in CYP2C8, CYP2C9, UGT1A6, PPARdelta and PPARgamma act as modifiers of the protective effect of regular NSAID use on the risk of colorectal carcinoma. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:713–721. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000174786.85238.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang J, Gajalakshmi V, Wang J, Kuriki K, Suzuki S, Nakamura S, Akasaka S, Ishikawa H, Tokudome S. Influence of the C161T but not Pro12Ala polymorphism in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma on colorectal cancer in an Indian population. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:507–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogel U, Christensen J, Dybdahl M, Friis S, Hansen RD, Wallin H, Nexo BA, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Andersen PS, Overvad K, Tjonneland A. Prospective study of interaction between alcohol, NSAID use and polymorphisms in genes involved in the inflammatory response in relation to risk of colorectal cancer. Mutat Res. 2007;624:88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siezen CL, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Peeters PH, Kram NR, van Doeselaar M, van Kranen HJ. Polymorphisms in the genes involved in the arachidonic acid-pathway, fish consumption and the risk of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:297–303. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Nava GA, Burguete-Garcia AI, Lopez-Carrillo L, Hernandez-Ramirez RU, Madrid-Marina V, Cebrian ME. PPARgamma and PPARGC1B polymorphisms modify the association between phthalate metabolites and breast cancer risk. Biomarkers. 2013;18:493–501. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2013.816776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu MH, Chu CH, Chou YC, Chou WY, Yang T, Hsu GC, Yu CP, Yu JC, Sun CA. Joint effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma genetic polymorphisms and estrogen-related risk factors on breast cancer risk: results from a case-control study in Taiwan. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:777–784. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallicchio L, McSorley MA, Newschaffer CJ, Huang HY, Thuita LW, Hoffman SC, Helzlsouer KJ. Body mass, polymorphisms in obesity-related genes, and the risk of developing breast cancer among women with benign breast disease. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, McCullough ML, Stevens VL, Rodriguez C, Jacobs EJ, Teras LR, Pavluck AL, Thun MJ, Calle EE. Nested case-control study of energy regulation candidate gene single nucleotide polymorphisms and breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:589–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Memisoglu A, Hankinson SE, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ. Lack of association of the codon 12 polymorphism of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma gene with breast cancer and body mass. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:597–603. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogel U, Christensen J, Nexo BA, Wallin H, Friis S, Tjonneland A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated [corrected] receptor-gamma2 [corrected] Pro12Ala, interaction with alcohol intake and NSAID use, in relation to risk of breast cancer in a prospective study of Danes. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:427–434. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Justenhoven C, Hamann U, Schubert F, Zapatka M, Pierl CB, Rabstein S, Selinski S, Mueller T, Ickstadt K, Gilbert M, Ko YD, Baisch C, Pesch B, Harth V, Bolt HM, Vollmert C, Illig T, Eils R, Dippon J, Brauch H. Breast cancer: a candidate gene approach across the estrogen metabolic pathway. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108:137–149. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9586-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinheiro SP, Gates MA, De Vivo I, Rosner BA, Tworoger SS, Titus-Ernstoff L, Hankinson SE, Cramer DW. Interaction between use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and selected genetic polymorphisms in ovarian cancer risk. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2010;1:320–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith WM, Zhou XP, Kurose K, Gao X, Latif F, Kroll T, Sugano K, Cannistra SA, Clinton SK, Maher ER, Prior TW, Eng C. Opposite association of two PPARG variants with cancer: overrepresentation of H449H in endometrial carcinoma cases and underrepresentation of P12A in renal cell carcinoma cases. Hum Genet. 2001;109:146–151. doi: 10.1007/s004390100563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bazargani A, Khoramrooz SS, Kamali-Sarvestani E, Taghavi SA, Saberifiroozi M. Association between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma gene polymorphism (Pro12Ala) and Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric carcinogenesis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1162–1167. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.499959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prasad KN, Saxena A, Ghoshal UC, Bhagat MR, Krishnani N. Analysis of Pro12Ala PPAR gamma polymorphism and Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric adenocarcinoma and peptic ulcer disease. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1299–1303. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tahara T, Arisawa T, Shibata T, Nakamura M, Wang F, Maruyama N, Kamiya Y, Nakamura M, Fujita H, Nagasaka M, Iwata M, Takahama K, Watanabe M, Hirata I, Nakano H. Influence of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)gamma Plo12Ala polymorphism as a shared risk marker for both gastric cancer and impaired fasting glucose (IFG) in Japanese. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:614–621. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9944-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao SY, Zeng ZR, Leung WK, Zhou SZ, Chen B, Sung JJ, Hu PJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma Pro12Ala polymorphism, Helicobacter pylori infection and non-cardia gastric carcinoma in Chinese. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim WY, Chen Y, Ali SM, Chuah KL, Eng P, Leong SS, Lim E, Lim TK, Ng AW, Poh WT, Tee A, Teh M, Salim A, Seow A. Polymorphisms in inflammatory pathway genes, host factors and lung cancer risk in Chinese female never-smokers. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:522–529. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campa D, Zienolddiny S, Maggini V, Skaug V, Haugen A, Canzian F. Association of a common polymorphism in the cyclooxygenase 2 gene with risk of non-small cell lung cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:229–235. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogel U, Christensen J, Wallin H, Friis S, Nexo BA, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Overvad K, Tjonneland A. Polymorphisms in genes involved in the inflammatory response and interaction with NSAID use or smoking in relation to lung cancer risk in a prospective study. Mutat Res. 2008;639:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang YTC, Mao W. The Pro12Ala polymorphism of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma 2 gene in lung cancer. Zhejiang Medicine. 2007;29:1257–1259. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kopp TI, Friis S, Christensen J, Tjonneland A, Vogel U. Polymorphisms in genes related to inflammation, NSAID use, and the risk of prostate cancer among Danish men. Cancer Genet. 2013;206:266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang MH, Helzlsouer KJ, Smith MW, Hoffman-Bolton JA, Clipp SL, Grinberg V, De Marzo AM, Isaacs WB, Drake CG, Shugart YY, Platz EA. Association of IL10 and other immune response- and obesity-related genes with prostate cancer in CLUE II. Prostate. 2009;69:874–885. doi: 10.1002/pros.20933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paltoo D, Woodson K, Taylor P, Albanes D, Virtamo J, Tangrea J. Pro12Ala polymorphism in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) gene and risk of prostate cancer among men in a large cancer prevention study. Cancer Lett. 2003;191:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00617-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tang H, Dong X, Hassan M, Abbruzzese JL, Li D. Body mass index and obesity- and diabetes-associated genotypes and risk for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:779–792. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mossner R, Meyer P, Jankowski F, Konig IR, Kruger U, Kammerer S, Westphal G, Boettger MB, Berking C, Schmitt C, Brockmoller J, Ziegler A, Stapelmann H, Kaiser R, Volkenandt M, Reich K. Variations in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma gene and melanoma risk. Cancer Lett. 2007;246:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou XP, Smith WM, Gimm O, Mueller E, Gao X, Sarraf P, Prior TW, Plass C, von Deimling A, Black PM, Yates AJ, Eng C. Over-representation of PPARgamma sequence variants in sporadic cases of glioblastoma multiforme: preliminary evidence for common low penetrance modifiers for brain tumour risk in the general population. J Med Genet. 2000;37:410–414. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.6.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogel U, Christensen J, Wallin H, Friis S, Nexo BA, Tjonneland A. Polymorphisms in COX-2, NSAID use and risk of basal cell carcinoma in a prospective study of Danes. Mutat Res. 2007;617:138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murtaugh MA, Ma KN, Caan BJ, Sweeney C, Wolff R, Samowitz WS, Potter JD, Slattery ML. Interactions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor {gamma} and diet in etiology of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1224–1229. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]