Abstract

As worldwide life expectancy rises, the number of candidates for surgical treatment of gastric carcinoma over 70 years will increase. This study aims to examine outcomes after gastric carcinoma in elderly patients. This study is a retrospective review of 697 patients undergoing gastrectomy with radical intent for gastric carcinoma during January 2007 to January 2013. A total of 534 patients were less than 70 years old (group A), and 163 patients 70 years or greater (group B). We analyzed the effect of age on short and long-term variables including overall survival and disease-free survival. Major morbidity was observed to occur in 19 patients of group A, and 15 of group B. Mortality, both 30-day and 90-day was observed in 1 and 3 of group A, and 3 and 6 of group B. Five-year overall survival and disease-free survival was 61% and 60% for group A, 50% and 43% for group B respectively. Gastrectomy should be carefully considered in patients 70 years old and can be justified with low mortality and acceptable long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Gastric carcinoma, gastrectomy, elderly age

Introduction

Gastric carcinoma is a disease that specially affects the elderly, showing a peak incidence after age 60 [1]. Moreover, recent studies have reported that patients over 70 years old have an increased incidence of gastric carcinoma [2]. Gastric carcinoma in the elderly often occurs in patients with significant comorbidities contributing to the complexity of a treatment strategy [3-7]. As worldwide actuarial life expectancy increases, the number of candidates for radical gastrectomy over 70 years old will progressively increase.

Controversy around the candidacy of elderly patients to tolerate radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy remains primarily in 2 forms; whether age by itself is an independent risk factor for complications and death, and whether there is a survival benefit from radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy in the elderly [6-8]. Several single-institution series have reported greater rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality in the elderly age group when compared with their younger counterparts, while others have reported similar outcomes [9]. This study aims to examine short and long-term outcomes after radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy in elderly patients (≥70 years old) when compared with younger counterparts.

Patients and methods

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki rules. This retrospective research was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. The need for informed consent from all patients was waived because this was retrospective study.

The study population includes consecutive patients undergoing gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy with radical intent for operable gastric carcinoma at our institution between January 2007 and January 2013. Surgical techniques for gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy was mainly determined by tumor location. Laparoscopic radical gastrectomy was performed in some cases. Additional exclusions include those patients undergoing multivisceral resection. Demographics, clinicopathologic data, short-term and long-term outcomes were recorded. The tumor stage of gastric cancer was based on the 7th edition of the TNM classification of gastric cancer, which was proposed by Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA) and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) [10-12]. The lymph nodes staging was based on the 3rd English edition of Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma proposed by JGCA [10-12]. For those of the patients operated before 2010, their staging was recalculated to match the latest TNM edition by UICC, JGCA and AJCC.

Upper endoscopy was performed on all patients, whereupon a diagnosis of gastric carcinoma was confirmed. All patients were evaluated with endoscopic ultrasonography, computed tomographic scans of brain, chest, and abdomen, and ultrasonography of abdomen. Positron emission tomography-computerized tomography (PET-CT), staging laparoscopy and bone scanning were performed in selected cases. Pulmonary function tests were routinely obtained and cardiac stress testing if risk factors were present.

For distal gastrectomy, the D2 lymphadenectomy in our study were as follows: right cardiac lymph nodes (No. 1 station), lesser curvature lymph nodes (No. 3 station), lymph nodes along the left gastroepiploic vessels (No. 4sb station), lymph nodes along the right gastroepiploic vessels (No. 4d station), suprapyloric lymph nodes (No. 5 station), infrapyloric lymph nodes (No. 6 station), left gastric artery lymph nodes (No. 7 station), common hepatic artery lymph nodes of anterosuperior group (No. 8a station), coeliac artery lymph nodes (No. 9 station), lymph nodes along the proximal splenic artery (No. 11p station) and lymph nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament (No. 12a station). For total gastrectomy, the D2 lymphadenectomy in our study were as follows: the lymph nodes dissected in distal gastrectomy, lesser curvature lymph nodes (No. 3 station), lymph nodes along the short gastric vessels (No. 4sa station), lymph nodes at the splenic hilum (No. 10 station) and lymph nodes along the distal splenic artery (No. 11d station).

Long-term follow up data were obtained from our follow-up database. The overall survival was assessed from the date of gastrectomy until the last follow up or death of any cause. The disease-free survival was calculated from the date of gastrectomy until the date of cancer recurrence or death of any cause. Disease recurrence was defined as locoregional recurrence, peritoneal recurrence or distant metastasis [13-16], proven by radiology or pathology. The last follow up was January 2015.

For statistical analysis, SPSS 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. For variables following normal distribution, data were presented as mean and standard deviations and were analyzed by student t test. For variables following non-normal distribution, data were expressed as median and range and were compared by Mann-Whitney U-test. Differences of semiquantitative results were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U-test. Differences of qualitative results were analyzed by chi-square test or Fisher exact test where appropriate. Survival rates were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method; differences between the two groups were analyzed with the log-rank test. Univariate analyses were performed to identify prognostic variables related to overall survival and disease-free survival. Univariate variables with probability values less than 0.05 were selected for inclusion in the multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression model. Adjusted odds ratios (HR) along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Search of our prospectively structured database revealed 697 consecutive patients who underwent gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy with curative intent between January 2007 and January 2012.

Patients were divided into 2 groups based on age. Of these, 534 patients were less than 70 years old (group A), and 163 patients were 70 years old or greater (group B). Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. The frequency of comorbidities, number of comorbidities, and higher ASA score were significantly higher in the 70 years old or greater (group B).

Table 1.

Demographics of patients undergoing gastrectomy

| <70 years (n=534) | ≥70 years (n=163) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 59 (41-68) | 75 (70-81) | 0.000 |

| Gender (Male:Female) | 326:208 | 101:62 | 0.834 |

| Comorbidities | 0.009 | ||

| Coronary artery disease | 12 | 8 | |

| Hypertension | 23 | 19 | |

| Chronic atrial fibrillation | 6 | 16 | |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 8 | 29 | |

| Chronic heart failure | 2 | 11 | |

| Perihpheral vascular disease | 2 | 6 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 | 4 | |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 1 | 5 | |

| Cirrhosis | 2 | 6 | |

| Number of comorbidities | 0.000 | ||

| 0 | 478 | 66 | |

| 1 | 55 | 92 | |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| ≥3 | 0 | 2 | |

| ASA score | 0.000 | ||

| I | 494 | 107 | |

| II | 39 | 52 | |

| III | 1 | 4 | |

| Clinical TNM stage | 0.475 | ||

| I | 26 | 11 | |

| II | 369 | 102 | |

| III | 139 | 50 |

Total gastrectomy was the most frequent type of gastrectomy in our study population, followed by distal gastrectomy (Table 2). The type of gastrectomy, the operative time and estimated blood loss were similar in the two groups. patients in group A (<70 years) spent a median of 12 days of postoperative hospital stay, patients in group B (≥70 years) spent 15 days (P=0.020). There were no significant differences in pathological stage (P=0.235) and differentiation (P=0.598).

Table 2.

Operative and pathological stage

| <70 years (n=534) | ≥70 years (n=163) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of gastrectomy | 0.623 | ||

| Total gastrectomy | 368 | 109 | |

| Distal gastrectomy | 166 | 54 | |

| Operative time (min) | 190 (150-300) | 180 (160-240) | 0.258 |

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | 354 (190-600) | 328 (160-520) | 0.840 |

| Length of postoperative stay (days) | 12 (6-32) | 15 (9-39) | 0.020 |

| Histological differentiation | 0.598 | ||

| Differentiated | 279 | 89 | |

| Undifferentiated | 255 | 74 | |

| Pathological TNM stage (7th UICC) | 0.235 | ||

| IB | 12 | 3 | |

| IIA | 103 | 36 | |

| IIB | 156 | 52 | |

| IIIA | 118 | 32 | |

| IIIB | 72 | 26 | |

| IIIC | 73 | 14 |

The distribution of complications, morbidity occurring within 30 postoperative days, according to age groups can be observed in Table 3. The severity of postoperative complications was graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. Major complications were defined as grades 3, 4 and 5. Minor complications were classified as 1 and 2. The detail of Clavien-Dindo classification has been reported elsewhere [17]. The overall complications and major complications were higher in group B (≥70 years) (P=0.0.002 and 0.007, respectively). Mortality at 30 days and at 90 days were higher in group B (≥70 years) (P=0.000).

Table 3.

Postoperative course in patients undergoing gastrectomy

| <70 years (n=534) | ≥70 years (n=163) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall complications n (%) | 57 (10.7%) | 33 (20.2%) | 0.002 |

| Major complications n | 19 | 15 | 0.007 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 3 | 4 | |

| Anastomosis leakage | 10 | 8 | |

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | 3 | 2 | |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 3 | 1 | |

| Minor complications n | 38 | 18 | 0.147 |

| Wound infection | 11 | 6 | |

| Ileus | 16 | 7 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 6 | 3 | |

| Atelectasis | 5 | 2 | |

| Mortality | 0.000 | ||

| 30 day | 1 | 2 | |

| 90 day | 3 | 6 |

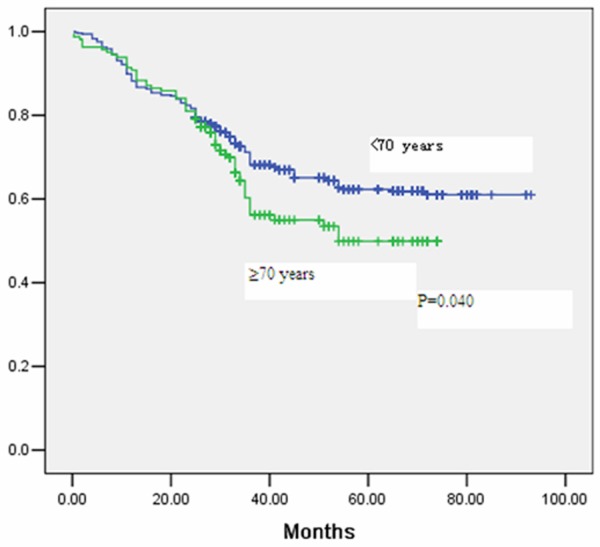

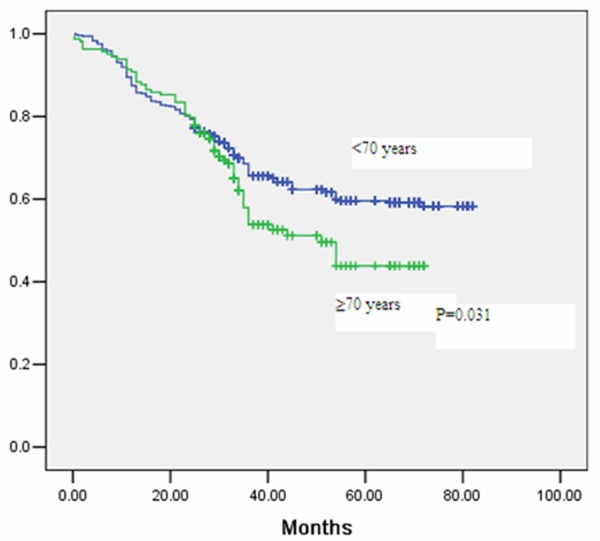

The median follow-up period was 43 months in the whole cohort. Five-year overall survival was 61% for patients in group A (<70 years), and 50% in group B (≥70 years) as seen in Figure 1 (P=0.040). Multivariate analysis for overall survival can be observed in Table 4. Five-year disease-free survival was 60% for patients in group A (<70 years), and 43% in group B (≥70 years), as seen in Figure 2 (P=0.031). Advanced age was seen to be significantly associated with a decrease in overall survival and disease-free survival in multivariate analysis, even when adjusting for cancer differentiation, pathological TNM stage, adjuvant therapy, and major postoperative complications (Tables 4 and 5).

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier curve for overall survival after gastrectomy stratified by age group.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis for overall survival in patients undergoing gastrectomy

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <70 years | 1.00 | |

| ≥70 years | 2.78 (1.59-5.847) | 0.023 |

| Cancer differentiation | ||

| Differentiated | 1.00 | |

| Undifferentiated | 1.89 (0.39-3.80) | 0.658 |

| pathological TNM stage | ||

| I | 1.00 | |

| II | 1.68 (0.58-3.41) | 0.558 |

| III | 3.58 (1.58-5.03) | 0.035 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | |

| No | 1.98 (0.36-2.58) | 0.487 |

| Major postoperative complications | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.98 (1.19-5.56) | 0.001 |

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier curve for disease-free survival after gastrectomy stratified by age group.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis for disease-free survival in patients undergoing gastrectomy

| Factors | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <70 years | 1.00 | |

| ≥70 years | 3.58 (1.98-5.98) | 0.030 |

| Cancer differentiation | ||

| Differentiated | 1.00 | |

| Undifferentiated | 2.58 (0.28-1.58) | 0.089 |

| pathological TNM stage | ||

| I | 1.00 | |

| II | 2.36 (0.50-3.25) | 0.254 |

| III | 4.52 (2.15-4.87) | 0.025 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| Yes | 1.00 | |

| No | 1.36 (0.15-1.35) | 0.487 |

| Major postoperative complications | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 2.69 (1.25-3.98) | 0.002 |

Discussion

Life expectancy worldwide is growing, and it is anticipated that by the year 2050 at least 16% of the world’s population will be at least 65 years old. Age 70 or greater was used in this analysis because most of the previous literature defines 70 years as a cutoff for the elderly people [18-24]. Previous literatures reported that worse prognosis was observed in patients 70 years old compared with younger patients [18-24]. Our data support similar observations of published series on gastrectomy in the elderly where patients 70 years or older exhibited a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease and pulmonary diseases compared with patients less than 70 years. In contrast to some reports [18-21], we observed a significant increase in postoperative 30-day complications in patients greater than 70 years at 20.2% compared with 10.7% in patients younger than 70 years. Despite these observations, postoperative hospital stay was only 3 day longer (median 15 days) in the patients 70 years or older compared with 12 days in patients less than 70 years.

To the best of knowledge, there is no report that document 90-day mortality after radical gastrectomy. Postoperative 30-day and 90-day mortality in our study was 1.2% and 3.7% in patients 70 years or older, while it was 0.18% and 0.56% for patients less than 70 years. We observed a 6.6-fold increase in 90-day mortality in patients undergoing radical gastrectomy in patients greater than 70 years or greater. Multivariate analysis confirmed that higher age and higher major postoperative complications were independent predictors of overall survival and disease-free survival in our series. Although there is some controversy regarding the influence of age on postoperative complications after radical gastrectomy, the majority of publications report 30-day mortality rates of 0.00% to 1.9% in patients less than 70 years and 1.2% to 2.6% in patients older than 70 years, which were significantly different [22-24].

Increasing age was associated with reduced overall survival and disease-free survival in patients undergoing radical gastrectomy in our series. This phenomenon can be attributed to comorbidities and reduced physiologic reserve in patients 70 years or older; however, decreased disease-free survival may be related to impaired immunosurveillance in the elderly patients. The disease-free survival rates have been reported to be similar between age groups or to be decreased in elderly patients.

This study has several limitations. There is an inherent selection bias in choosing patients for radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy. Although some objective criteria (Karnofsky performance score, ASA score, comorbidities, and clinical TNM stage) were used to deny patients a radical resection, surgeons’ judgment was difficult to measure. Furthermore, adjuvant chemotherapy was employed less frequently with advancing age compared with younger patients. This phenomenon may contribute to worse long-term prognosis. Quality of life assessment was not analyzed in this cohort and represents a major limitation, which will be part of a subsequent study.

In conclusion, elderly patients with gastric carcinoma show more frequently with comorbidities, when compared with patients less than 70 years. More specifically, they have higher rates of postoperative morbidity and mortality, and decreased overall and disease-free survival rates. Multivariate analysis of the significant variables in this study did not identify tumor differentiation, tumor subtype, cancer stage, or gender as independent predictors of poor prognosis in the elderly. It is more evident that offering radical gastrectomy to patients greater than 70 years requires careful consideration and should be performed in centers of excellence.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the patients, their families and our hospital colleagues who participated in this research.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Correa P. Gastric cancer: overview. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2013;42:211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piazuelo MB, Correa P. Gastric cáncer: Overview. Colomb Med (Cali) 2013;44:192–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bi YM, Chen XZ, Jing CK, Zhou RB, Gao YF, Yang LB, Chen XL, Yang K, Zhang B, Chen ZX, Chen JP, Zhou ZG, Hu JK. Safety and survival benefit of surgical management for elderly gastric cancer patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1801–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeon TY, Kim DH, Son GM, Lee SH, Hwang SH. Risk factors for delayed gastric emptying caused by anastomosis edema after subtotal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1794–1800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato H, Kitani K, Isono S, Takeyama H, Yukawa M, Inoue M, Kanaizumi H. Comparison of gastric cancer surgery between patients aged>80 years and<79 years: complications and multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:1785–1793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu JF, Yang B, Fang L, Li YP, Shi YJ, Yu XC, Zhang MC. Safety and efficacy of laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer in the elderly. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:3562–3567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emir S, Sözen S, Bali I, Gürdal SÖ, Turan BC, Yıldırım O, Yetişyiğit T. Outcome analysis of laporoscopic D1 and D2 dissection in patients 70 years and older with gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:3501–3511. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oya H, Komatsu Y, Shimizu D, Koike S, Tagami K, Kodera Y. Curative surgery for gastric cancer of the elderly in a Japanese regional hospital. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:1673–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coniglio A, Tiberio GA, Busti M, Gaverini G, Baiocchi L, Piardi T, Ronconi M, Giulini SM. Surgical treatment for gastric carcinoma in the elderly. J Surg Oncol. 2004;88:201–205. doi: 10.1002/jso.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3) Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sano T, Aiko T. New Japanese classifications and treatment guidelines for gastric cancer: revision concepts and major revised points. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:97–100. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tegels JJ, De Maat MF, Hulsewé KW, Hoofwijk AG, Stoot JH. Improving the outcomes in gastric cancer surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13692–13704. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fock KM. Review article: the epidemiology and prevention of gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:250–160. doi: 10.1111/apt.12814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yegin EG, Duman DG. Staging of esophageal and gastric cancer in 2014. Minerva Med. 2014;105:391–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foo M, Crosby T, Rackley T, Leong T. Role of (chemo)-radiotherapy in resectable gastric cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2014;26:541–550. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH, Nam BH, Ryu KW. Tumor differentiation is not a risk factor for lymph node metastasis in elderly patients with early gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1771–1776. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim JH, Lee DH, Shin CM, Kim N, Park YS, Jung HC, Song IS. Clinicopathological features and surgical safety of gastric cancer in elderly patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:1639–1645. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.12.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eguchi T, Fujii M, Takayama T. Mortality for gastric cancer in elderly patients. J Surg Oncol. 2003;84:132–136. doi: 10.1002/jso.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunisaki C, Akiyama H, Nomura M, Matsuda G, Otsuka Y, Ono HA, Shimada H. Comparison of surgical outcomes of gastric cancer in elderly and middle-aged patients. Am J Surg. 2006;191:216–124. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pisanu A, Montisci A, Piu S, Uccheddu A. Curative surgery for gastric cancer in the elderly: treatment decisions, surgical morbidity, mortality, prognosis and quality of life. Tumori. 2007;93:478–484. doi: 10.1177/030089160709300512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saif MW, Makrilia N, Zalonis A, Merikas M, Syrigos K. Gastric cancer in the elderly: an overview. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:709–717. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirashima K, Watanabe M, Shigaki H, Imamura Y, Ida S, Iwatsuki M, Ishimoto T, Iwagami S, Baba Y, Baba H. Prognostic significance of the modified Glasgow prognostic score in elderly patients with gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1040–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0855-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]