Abstract

Background: Pain is the most common complaint of patients on the first day after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC). The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of local anesthesia with bupivacaine and intravenous parecoxib on postoperative abdominal pain relief up to 24 h after surgery. Methods: One hundred and eighty patients who underwent LC were randomized to one of three groups with sixty patients each: Group A received 50 mg 0.5% bupivacaine subcutaneously at trocar sites before incision closure; Group B received intravenous parecoxib (40 mg) after entering the recovery room; Group C did not receive postoperative analgesia unless needed and was served as control. The postoperative pain at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after the operation was assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS). Secondary outcomes, including intraoperative and postoperative complications, the incidence of shoulder pain, pethidine requirements, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and hospital stay were also recorded. Results: At 1, 2, and 4 hours after surgery, VAS pain scores were significantly lower in group A and B compared with group C (P < 0.05 for all). There was no significant difference among the three groups at 8, 12, and 24 hours after the procedure (P > 0.05 for all). A repeated-measures ANOVA analysis revealed that VAS pain scores over the first 24 hours after LC were significantly lower in group A and B compared with group C (P = 0.014 and P = 0.029 for between-group comparison, respectively). Furthermore, the percentage of patients requiring postoperative rescue analgesics was significantly higher in group C as compared with group A and group B (P = 0.018). Conclusion: Local anesthesia with bupivacaine and intravenous parecoxib are both effective at decreasing postoperative pain and pethidine requirements after LC.

Keywords: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, postoperative pain, bupivacaine, parecoxib

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is considered the gold standard for the treatment of symptomatic gallstone disease [1]. LC is associated with less postoperative pain, reduced analgesic consumption, shorten the recovery period, and shorter hospital stay, as compared with traditional open procedure [2]. In spite of this, the severity of postoperative abdominal and shoulder pain is still significant, which restricts LC as a same-day procedure in a substantial number of patients. The pathophysiological mechanisms that contribute to postoperative pain are initiated by tissue damage resulting from surgical incisions, removal of the gallbladder from the liver bed, stretching of nerve endings and irritation of the diaphragm by carbon dioxide. These factors trigger peripheral nerve endings and cause pain [3]. Moreover, the process of central sensitization increases postoperative perceived pain in the area of tissue damage and in the surrounding areas as well [4].

Various studies have been performed for reducing the pain after LC by blocking these sites using subcutaneous infiltration or intraperitoneal instillation of long-acting local anesthetics such as bupivacaine, ropivacaine, and levobupivacaine [5-8]. However, the efficacy of local anesthetics is still controversial. The injectable COX-2 inhibitor, parecoxib, which is a selective class of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), could play an important role in perioperative pain management by reducing the inflammatory response in the periphery, modulating nociceptors, and attenuating central sensitization [9]. Although several trials have evaluated the efficacy of parecoxib, evidence comparing parecoxib as an alternative to local anesthetics is lacking.

The aim of this randomized controlled trial was to compare the efficacy of local anesthesia with bupivacaine versus intravenous parecoxib on postoperative pain relief within the first 24 hours after LC.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study was conducted at the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital between March 2013 and May 2014. The study has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before operation. Patients with symptomatic gallstone disease were candidates for inclusion in this study. Exclusion criteria for safety and standardization were: (1) age below 18 years or over 80 years; (2) pregnancy; (3) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade III or higher; (4) acute cholecystitis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis; (5) had significant comorbid diseases of liver, kidneys, or heart; (6) history of alcohol or drug addiction; (7) allergy to the study drugs; (8) chronic pain syndrome or chronic narcotic use.

One hundred and eighty patients were randomized to one of three groups with sixty patients each according to a computer generated randomization list. The patients in Group A received 50 mg 0.5% bupivacaine (diluted with 10 ml normal saline at 1:1 ratio), which was infiltrated subcutaneously at trocar sites before incision closure. The patients in Group B received intravenous parecoxib (40 mg) after entering the recovery room. The patients in Group C did not receive postoperative analgesia unless needed. The demographic and clinical data that included patient age, gender, body mass index (BMI), clinical diagnosis, and ASA physical status were recorded.

Surgical procedure

All the surgical procedures were performed by the same surgical team. After induction of anesthesia, all the patients were placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position (30°). LC was performed using the standard three-port technique, which consists of a 10-mm port via the umbilical incision, a 10-mm port in the epigastric area, and a 5-mm trocar at the right anterior axillary line. Pneumoperitoneum was created through umbilical trocar with CO2 and intra-abdominal pressure was maintained at 10-12 mmHg during the whole procedure. The cystic duct and artery were clipped with absorbable clips (Lapro-Clip; Tyco Healthcare, Covidien, Norwalk, Conn., USA). The gallbladder was then dissected free off the liver bed with hook cautery and removed with a plastic bag through the umbilical port site. Vicryl 1-0 (Ethicon Inc., Johnson&Johnson, Somerville, New Jersey, USA) was used for closure of the transverse fascia at the 10-mm trocar sites and Ethilon 4-0 (Ethicon Inc.) for skin closure. In patients of Group A, bupivacaine was infiltrated subcutaneously at trocar sites before incision closure.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was postoperative abdominal pain as measured by a visual analog scale (VAS) of 0 to 10, where 0 corresponds to no pain at all and 10 indicates the worst pain ever experienced by the patient. The patient was asked to indicate a score from 0 to 10 corresponding to the perceived pain at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after the operation. If the score 6 or higher on VAS at any of the postoperative visits were noted, 100 mg pethidine intramuscular injection was given.

Secondary outcome measures included: intraoperative complications, including bile duct injury, perforation of the gallbladder (bile spillage), and bleeding that necessitated intervention; shoulder pain; nausea and vomiting; pethidine requirements; postoperative complications during the hospital admission; and length of hospital stay.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables (operative time, anesthesia time, postoperative activity time, hospital stay, pain scores) were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed using independent t-test. Categorical variables (gender and ASA score were depicted as male-to-female ratio and I/II ratio) were recorded as numbers (percentages) and compared using the χ2 test. For VAS, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) model was used to compare the overall efficacy of interventions across six time intervals. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

One hundred and eighty patients were eligible after evaluation and were allocated to one of three groups. Thirteen patients were excluded from the analysis; seven patients had Jackson-Pratt drain placement at the end of the procedure due to bile spillage at the surgical bed, and in the other six patients the procedure was converted to open cholecystectomy owing to inability to determine the anatomical structures adequately. Baseline characteristics and clinical data of the three groups are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences among the three groups with respect to age, gender, BMI, the ASA grade, anesthesia time, operation time, postoperative activity time, and length of hospital stay.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and clinical data of the study participants

| Characteristics | Group A (n = 60) | Group B (n = 60) | Group C (n = 60) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 56.6 | 56.6 | 51.0 | 0.1924 |

| Gender (M/F) | 18/42 | 18/42 | 25/35 | 0.3317 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.7 | 25.0 | 25.1 | 0.7496 |

| ASA grade (I/II) | 50/10 | 44/16 | 46/14 | 0.5638 |

| Anesthesia time (min) | 62.0 | 66.8 | 66.4 | 0.6492 |

| Operation time (min) | 51.4 | 54 | 54.7 | 0.3661 |

| Postoperative activity time (h) | 10.6 | 11.2 | 10.6 | 0.4528 |

Group A: 50 mg 0.5% bupivacaine, Group B: intravenous parecoxib (40 mg), Group C: did not receive postoperative analgesia unless needed. n = number of patients; M/F: male-to-female ratio; BMI = body mass index; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status.

Primary outcome measure

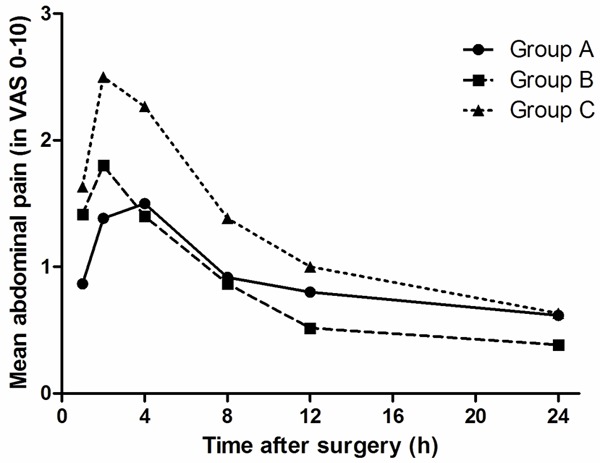

Figure 1 shows the abdominal pain scores for the experimental and control groups during the first 24 h after surgery. At 1, 2, and 4 hours after surgery, VAS pain scores were significantly lower in group A and B compared with group C (P < 0.05 for all). There was no significant difference among the three groups at 8, 12, and 24 hours after the procedure (P > 0.05 for all). A repeated-measures ANOVA analysis revealed that VAS pain scores over the first 24 hours after LC were significantly lower in group A and B compared with group C (P = 0.014 and P = 0.029 for between-group comparison, respectively).

Figure 1.

Visual analogue scale scores at different time intervals during the first 24 h after surgery.

Secondary outcome measures

No major complications were observed within the first 24 hours after operation (Table 2). Nor were there any side-effects resulting from use of the trial medication. There was no significant difference in bile spillage rate, bleeding rate, incidence of nausea and vomiting, and length of hospital stay among the three groups (P > 0.05 for all). Group A had lower the incidence of shoulder pain than group B and group C (P = 0.022, Table 2). The percentage of patients requiring postoperative rescue analgesics was significantly higher in group C as compared with group A and group B (P = 0.018). All patients presented two weeks after surgery in the outpatient department, and no untoward or major complications were observed.

Table 2.

Secondary outcome measures

| Group A (n = 60) | Group B (n = 60) | Group C (n = 60) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bile spillage (N/Y) | 46/14 | 43/17 | 47/13 | 0.1448 |

| Bleeding (≤ 20 mL/> 20 mL) | 58/2 | 54/6 | 52/8 | 0.0734 |

| Shoulder pain (N/Y) | 54/6 | 43/17 | 47/13 | 0.0219 |

| Nausea and vomiting (N/Y) | 49/11 | 50/10 | 53/7 | 0.0563 |

| Pethidine requirements (N/Y) | 56/4 | 58/2 | 49/11 | 0.0182 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 0.3969 |

n = number of patients; N/Y = No/Yes.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that, compared with the control group, both local anesthesia with bupivacaine and intravenous parecoxib significantly reduced postoperative pain within the first 24 hours after LC. In an analysis of secondary outcomes, more patients required pethidine for analgesia in group C than group A and group B, which was consistent with the VAS pain scores.

The origins of pain after LC are multifactorial and include visceral pain from dissected peritoneum surrounding the gallbladder, somatic pain from retained intraperitoneal blood or bile, insufflation of carbon dioxide with distension of the parietal peritoneum and with traumatic injury related to the trocars [3,10]. Several trials have examined the above pain components and the results were controversial. Keith and his colleagues [11] assessed the efficacy of injection of bupivacaine to the anterior surface of the liver, gallbladder and porta hepatis during LC and found this does not influence postoperative pain. However, in another prospective randomized clinical trial, Francesco et al. [12] evaluated the effectiveness of 0.5% bupivacaine positioned in the gallbladder soaking a sheet of regenerated oxidized cellulose called “Tabotamp” and the result showed the use of local anesthetic soaking Tabotamp in the gallbladder bed is safe and not economically demanding and can provide advantages in increasing postoperative comfort. Intraperitoneal local anesthetic nebulization is another novel approach to pain management after LC [13]. This approach can provide uniform dispersion of local anesthetic particles throughout the peritoneal cavity [14]. However, the analgesic effectiveness of intraperitoneal local anesthetic nebulization may depend upon the nebulization device and the delivery mode. Alkhamesi and colleagues [15] reported that nebulization of bupivacaine using a custom-made device significantly reduced pain after LC. Compared with intraperitoneal ropivacaine instillation, nebulization of ropivacaine using a high-frequency vibrating membrane nebulizer reduced should pain and the time to unassisted walking after LC [16]. In contrast, Zimmer and colleagues [17] did not find significant differences in pain or analgesic consumption after bupivacaine nebulization using the Insuflow device.

Surgical incision is perhaps the most important pain component because it has been reported that incisional pain is more intense than visceral pain and is dominant during the first 48 h after LC [18]. Subcutaneous infiltration of local anesthetics at the port site has also been the subject of several trials. Liu et al. [19] reported that local anesthesia with ropivacaine at the port site in LC patients significantly decreased postoperative pain immediately. While in another randomized double-blind study, Papagiannopoulou et al. [20] concluded that local tissue infiltration with levobupivacaine is more effective than ropivacaine in reducing the postoperative pain associated with LC. In the present study, our findings indicated that infiltrating bupivacaine after LC through the port site reduced postoperative pain and the number of patients requiring postoperative analgesics than patients who did not receive postoperative local anesthesia.

Parecoxib, the first injectable COX-2 inhibitor, was introduced into clinical practice in 2001. It could provide effective pain control, in addition to a lesser degree of platelet dysfunction and gastrointestinal toxicity compared to nonselective NSAIDs [21]. It is now increasingly used in ambulatory or day-case surgery because it reduces opioid consumption, improves pain scores, and results in earlier hospital discharge and return to normal function [22]. In the present study, we observed a significant reduction in postoperative VAS scores within the first 24h after LC in patients who received parecoxib as compared with those who did not. The number of patients requiring pethidine was also lower in group B than in group C, which was in consistent with the pain scores. However, we did not observed any differences in length of hospital stay between patients who received parecoxib and those who did not. Therefore, parecoxib may not offer any benefit of length of hospital stay because LC is hard to improve upon.

In conclusion, local anesthesia with bupivacaine and intravenous parecoxib are both effective at decreasing postoperative pain after LC. Also, these two approaches decreases the number of patients who require postoperative rescue analgesics.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jian Gong, MD, for helping with the clinical data collection.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Soper NJ, Stockmann PT, Dunnegan DL, Ashley SW. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The new “gold standard”? Arch Surg. 1992;127:917–921. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420080051008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keus F, de Jong JA, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD006231. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hilvering B, Draaisma WA, van der Bilt JD, Valk RM, Kofman KE, Consten EC. Randomized clinical trial of combined preincisional infiltration and intraperitoneal instillation of levobupivacaine for postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2011;98:784–789. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618–1625. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68700-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moiniche S, Jorgensen H, Wetterslev J, Dahl JB. Local anesthetic infiltration for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopy: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review of intraperitoneal, port-site infiltration and mesosalpinx block. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:899–912. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200004000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kucuk C, Kadiogullari N, Canoler O, Savli S. A placebo-controlled comparison of bupivacaine and ropivacaine instillation for preventing postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Today. 2007;37:396–400. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Louizos AA, Hadzilia SJ, Leandros E, Kouroukli IK, Georgiou LG, Bramis JP. Postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a placebo-controlled double-blind randomized trial of preincisional infiltration and intraperitoneal instillation of levobupivacaine 0.25 per cent. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1503–1506. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-3002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papadima A, Lagoudianakis EE, Antonakis P, Filis K, Makri I, Markogiannakis H, Katergiannakis V, Manouras A. Repeated intraperitoneal instillation of levobupivacaine for the management of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2009;146:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reuben SS. Update on the role of nonsteroidal antiinflmmatory drugs and coxibs in the management of acute pain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2007;20:440–450. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3282effb1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindgren L. Pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Do we do our best? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1997;41:191–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1997.tb04663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts KJ, Gilmour J, Pande R, Hodson J, Lam FT, Khan S. Double-blind randomized sham controlled trial of intraperitoneal bupivacaine during emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12:310–316. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(13)60049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feroci F, Kroning KC, Scatizzi M. Effectiveness for pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy of 0.5% bupivacaine-soaked Tabotamp placed in the gallbladder bed: a prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2214–2220. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahokehr A, Sammour T, Soop M, Hill AG. Intraperitoneal use of local anaesthetic in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Hepatobiliary Pancreas Sci. 2010;17:637–656. doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greib N, Schlotterbeck H, Dow WA, Joshi GP, Geny B, Diemunsch PA. An evaluation of gas humidifying devices as a means of intraperitoneal local anesthetic administration for laparoscopic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:549–551. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318176fa1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alkhamesi NA, Peck DH, Lomax D, Darzi AW. Intraperitoneal aerosolization of bupivacaine reduces postoperative pain in laparoscopic surgery: a randomized prospective controlled double-blind clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:602–606. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bucciero M, Ingelmo PM, Fumagalli R, Noll E, Garbagnati A, Somaini M, Joshi GP, Vitale G, Giardini V, Diemunsch P. Intraperitoneal ropivacaine nebulization for pain management after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a comparison with intraperitoneal instillation. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:1266–1271. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31822d447f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmer PW, McCann MJ, O’Brien MM. Bupivacaine use in the Insuflow device during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a prospective randomized double-blind controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1524–1527. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0804-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee IO, Kim SH, Kong MH, Lee MK, Kim NS, Choi YS, Lim SH. Pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: the effect and timing of incisional and intraperitoneal bupivacaine. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48:545–550. doi: 10.1007/BF03016830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu YY, Yeh CN, Lee HL, Wang SY, Tsai CY, Lin CC, Chao TC, Yeh TS, Jan YY. Local anesthesia with ropivacaine for patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2376–2380. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papagiannopoulou P, Argiriadou H, Georgiou M, Papaziogas B, Sfyra E, Kanakoudis F. Preincisional local infiltration of levobupivacaine vs ropivacaine for pain control after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1961–1964. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9256-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akaraviputh T, Leelouhapong C, Lohsiriwat V, Aroonpruksakul S. Effiacy of perioperative parecoxib injection on postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective, randomized study. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2005–2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshi GP. Pain management after ambulatory surgery. Ambulatory Surg. 1999;7:3–12. [Google Scholar]