Abstract

Background

The effectiveness of intra-articular hyaluronic acid (IAHA) injection for knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is debated.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of IAHA for patients with KOA by analysing data from trials of IAHA versus placebo with low risk of bias, to provide the highest level of evidence.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with a low risk of bias (adequate randomisation and concealment and double-blind design) that investigated IAHA versus placebo (saline solution) injection were eligible. The primary efficacy measure was pain intensity and secondary outcome function at 3 months. The treatment effect was summarised with the standardised mean difference (SMD) calculated from differences in means of pain and function measures between treatment and control groups at 3 months. Trials were pooled by a random-effects model with DerSimonian and Laird weights. Statistical heterogeneity was explored by a visual exploration of forest plots and the I2 statistic.

Results

A total of eight RCTs (2 199 randomised patients) met our inclusion criteria. IAHA significantly reduced the pain intensity (SMD=−0.21, 95% CI (95% CI) −0.32 to −0.10) and improved function (SMD=−0.12, 95% CI −0.22 to −0.02). Trials showed no heterogeneity.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis of high-quality trials of IAHA versus placebo shows that IAHA provides a moderate but real benefit for patients with KOA.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Outcomes research, Treatment

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Several meta analyses have been conducted with hyaluronic acid that yielded conflicting results.

What does this study add?

This meta analysis was conducted with randomised controlled trials of low risk of bias to avoid any garbage in-garbage out phenomenon.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

This meta analysis supports the use of hyaluronic acid to alleviate pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis.

Introduction

Apart from its large impact on disability,1 knee osteoarthritis (KOA) has recently been found to be associated with increased risk of mortality.2 3 The main risk factors for this excess mortality are cardiovascular disease and walking disability,2 3 which highlights the importance of alleviating pain and improving function in such patients by promoting a non-sedentary lifestyle.

In clinical practice, both acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used as analgesics for OA. However, patients with KOA often have comorbidities such as obesity and hypertension,4 which precludes the use of such analgesics in all patients. Indeed, in addition to the well-known toxicity of NSAIDs,5 the effect of acetaminophen on OA symptoms are modest at best (effect size 0.18 (0.11–0.25).6 7 Also, recent data point to cardiovascular side effects and gastrointestinal toxicity, which raise concerns about the risk/benefit ratio of this widely prescribed drug.8

In addition to oral treatments, intra-articular hyaluronic acid (IAHA) are often used in daily practice for managing KOA. The effectiveness of IAHA, used for more than 20 years, has been much debated. Initially recommended by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI),9 the European League Against Rheumatism10 and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR),11 HA is now not recommended by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons12 and conditionally recommended by the ACR;13 the OARSI recently provided an uncertain recommendation.6

Expert opinion from these international societies was mainly based on results from meta-analyses (MAs), which are essential for evidence-based decision-making in clinical practice. Two of the last MAs of HA14 15 highlighted some pitfalls in the methodological quality of some randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of HA. This point is crucial because metaepidemiological studies have well demonstrated that the poor methodological quality of trials can be associated with a biased estimation of the treatment effect, which in turn can lead to biased estimations from the MA (‘garbage in—garbage out’).16

To clarify the debate on the efficacy of HA, we performed a new MA restricted to trials of IAHA with the lowest risk of bias. Indeed, such an MA is considered to provide the highest level of evidence available for evaluating an intervention.

Methods

This study is reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and MAs (PRISMA) checklist.17 It was performed according to a protocol established before the start of the literature search and data analysis.

Eligibility criteria

We included trials that met the following criteria: (1) RCT, (2) unconfounded comparison of IAHA to IA placebo injection (saline solution) in patients with KOA, and (3) highest methodological quality defined by adequate randomisation and concealment of randomisation and double-blind design. The criteria of low risk of bias were chosen from results of an explanatory analysis of subgroups by Rutjes et al15 and previous meta-epidemiological studies.18 19

Information source and search

We systematically searched MEDLINE via PubMed, EMBASE via OVID, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the last search performed in December 2013, for published original articles without any restriction on language. We used a search strategy of free text terms and MeSH terms relevant to HA, viscosupplementation and KOA. In a first step, we searched for the following terms: “Hyaluronic Acid” [MeSH Terms]+OR+“Viscosupplementation” [MeSH Terms]+OR+“Viscosupplements” [MeSH Terms])+AND+(“Osteoarthritis, Knee” [MeSH Terms])+AND+(Randomized Controlled Trial [pt]). In a second step, we searched for the subsequent terms: Hyaluronic Acid [MeSH Terms] OR Hyaluronic Acid [TIAB] OR hyaluronate [TIAB] OR Hyaluronan [TIAB] OR hyaluron [TIAB] OR hylan [TIAB] OR synvisc [TIAB] OR orthovisc [TIAB] OR ostenil [TIAB] OR suplasyn [TIAB] OR arthrum [TIAB] OR synovial [TIAB] OR artz [TIAB] OR biotty [TIAB] OR go-on [TIAB] OR healon [TIAB] OR hyaject [TIAB] OR hyalgan [TIAB] OR hyalart [TIAB] OR hyalectin [TIAB] OR nuflexxa [TIAB] OR euflexxa [TIAB] OR polireumin [TIAB] OR hygag [TIAB] OR nrd101 [TIAB] OR replasyn [TIAB] OR supartz [TIAB] OR artzal [TIAB] OR supartz [TIAB] OR Viscosupplementation [MeSH Terms] OR Viscosupplementation [TIAB] OR Viscosupplementations [TIAB] OR Viscosupplements [MeSH Terms] OR Viscosupplements [TIAB] AND Osteoarthritis, Knee [MeSH Terms] OR Knee Osteoarthritides [TIAB] OR Knee Osteoarthritis [TIAB] OR Osteoarthritis Of Knee [TIAB] OR Osteoarthritis Of Knees [TIAB]) AND (“clinical"[TIAB] AND “trial"[TIAB]) OR “clinical trials” [MeSH Terms] OR “clinical trial” [Publication Type] OR “random” [TIAB] OR “random allocation” [MeSH Terms] OR “therapeutic use” [MeSH Subheading]). We also searched the reference lists of all identified relevant studies and review articles, conference abstracts, books and the ClinicalTrials.gov registry for eligible articles.

Study selection

We screened titles and abstracts of identified articles and obtained the full-text article for potential reports for further assessment. Studies that did not meet all criteria were excluded.

Data collection process

Data extraction involved a computer-assisted standardised data-collection form with detailed instructions for data extraction and coding. From eligible articles, we collected data on study characteristics (sample size, number of treatment groups, study design, follow-up duration, funding source, registry number); patient characteristics (sex, age, duration of symptoms, disease severity); interventions (type of comparator, type, dose, intensity, and duration of treatment); outcome measures (mean (SD) baseline and final score, analysis of covariance estimates (SE) when available for each group); and information needed to assess the risk of bias and methodological quality.

Summary measures

The prespecified main outcome was pain intensity at a prespecified end point—3 months—or the nearest end point if missing, and the secondary outcome was physical function (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index or Lequesne index).

Synthesis of results

The impact of viscosupplementation compared with placebo (saline injection) was expressed as the standardised mean difference (SMD) with its 95% CI by the Hedges’ g estimator. The SMD is the mean divided by the standard deviation (SD) of the difference in pain or function between the viscosupplementation and placebo groups. Data were pooled using a random-effects model and the DerSimonian and Laird method20 to give a more conservative estimate of the effect of viscosupplementation, allowing for any heterogeneity between studies. To better appreciate the clinical relevance of the magnitude of the treatment effect, we used back-transformation of the SMD to an OR.21 22 The corresponding OR for the SMD was derived as follows: OR=exp (1.81*d). The OR estimating the relative risk is a more common measure of treatment effects than the SMD. This derived OR extrapolates the value of the OR that would have been obtained if a discretisation of the visual analog scale (VAS) had been performed with a treatment failure threshold. Thus, an OR=0.5 means that the treatment reduces, by dividing by 2, the odds of treatment failure (approximately the risk of treatment failure).

Risk of bias across studies

Statistical heterogeneity in study results was explored by a visual inspection of forest plots and quantified by I2 and τ2 statistics.23 Potential publication bias was explored by a visual inspection of funnel plots and Egger's test for funnel asymmetry.24

All analyses involved the use of R and the Meta package (R Core Team 2014).

Results

Study selection

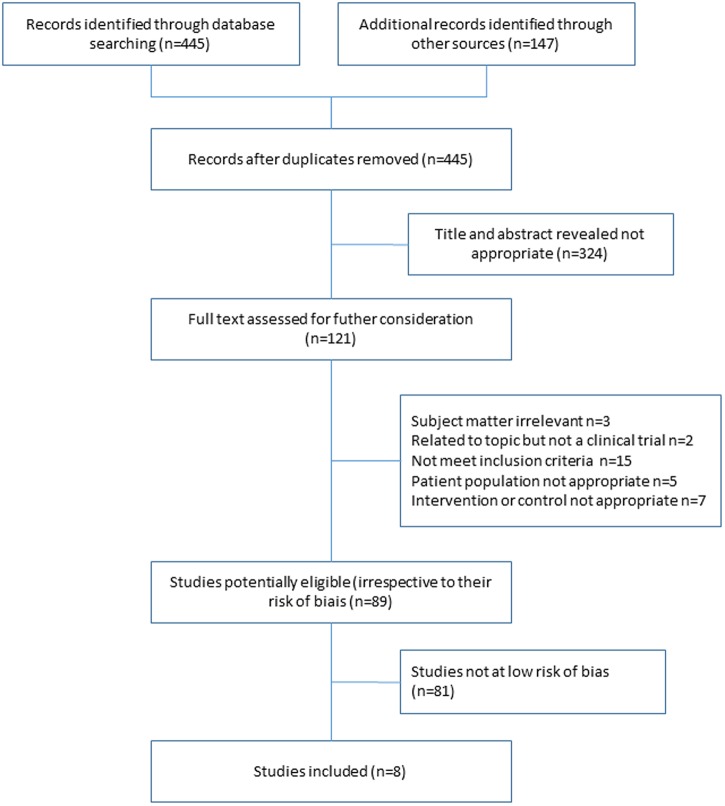

Our literature search yielded 445 potentially relevant articles. We added 147 references, and after excluding duplicates, reviews and non-eligible studies by reading the titles and abstracts, we retrieved 141 potential full-text papers. Finally, we included eight articles of trials of IAHA versus placebo (figure 1).25–32 Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included reports.

Figure 1.

Flow of the search for articles and trial assessment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis of intra-articular injection of HA versus placebo (saline solution)

| Author, year | Molecular weight of HA (kDa) | Number of injections/ number of cycles | Cross-linked | Industry funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shichikawa, 198325 | NA | 5/1 | No | Unclear |

| Puhl, 199326 | 900 | 5/1 | No | Yes |

| Altman, 200427 | 1000 | 1/1 | No | Yes |

| Petrella, 200629 | 600 | 3/1 | No | Yes |

| Lundsgaard, 200830 | 700 | 4/1 | No | Yes |

| Altman, 200928 | 3000 | 3/1 | No | Yes |

| Chevalier, 201032 | 6000 | 1/1 | Yes | Yes |

| Navarro-Sarabia, 201131 | 900 | 5/4 | No | Yes |

HA, hyaluronic acid; NA, not available.

Trial characteristics

Articles for the eight trials were published between 1983 and 2011 and randomised 2199 patients. All trials used a parallel-group design and all had an adequately generated random sequence, adequately concealed treatment allocation and adequately blinded patients and outcome assessors. The length of the studies ranged from 12 to 160 weeks and sample sizes from 168 to 588 (table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients included in the meta-analysis

| Trial | Age (years) |

Women (%) |

KL grade 3/4 (%) |

Level of pain |

BMI (kg/m2) |

Duration of symptoms (years) |

No randomised/ analysed (n) experimental control |

Time of assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shichikawa et al25 | NA | 83 | 24.5 | 63.5 (0–100) | NA | NA | 114/96 | 114/102 | 12 weeks |

| Puhl et al26 | 61 | 64 | NA | 52.7 (mm, VAS) | 26.9 | NA | 102/95 | 107/100 | 9 weeks |

| Altman et al27 | 63 | 55 | 38.5 | 10.1 (WOMAC) | 29.9 | 6 | 173/172 | 174/174 | 13 weeks |

| Petrella and Petrella29 | 63 | 45 | 25.6 | 20.3 (WOMAC) | 30.4 | NA | 53/53 | 53/53 | 40 months |

| Lundsgaard et al30 | 69 | 55 | 36.8 | 54.5 (mm, VAS) | 29.4 | 8 | 84/81 | 84/80 | 12 weeks |

| Altman et al28 | 62 | 63 | 60.0 | 55.1 (mm, VAS) | 32.7 | NA | 293/291 | 295/295 | 12 weeks |

| Chevalier et al32 | 63 | 71 | 54.4 | 2.27 (WOMAC) | 29.3 | 6 | 124/124 | 129/129 | 12 weeks |

| Navarro-Sarabia et al31 | 64 | 84 | 27.4 | 70.4 (mm, VAS) | 28.6 | 8 | 153/149 | 153/152 | 24 weeks |

BMI, body mass index; NA, not applicable; VAS, visual analog scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

Effect on joint pain

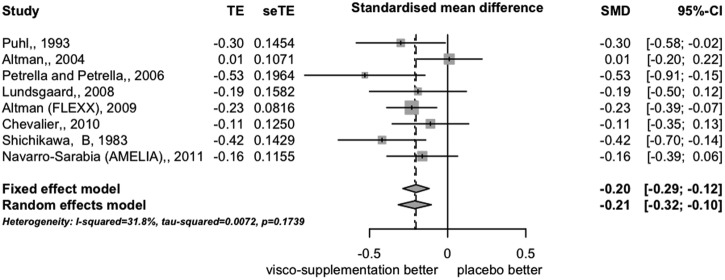

The eight trials provided data on pain level (VAS) at month 3. The SMD (random-effects model) was −0.21 (95% CI −0.32 to −0.10) favouring IAHA (figure 2), which corresponds to an OR of 0.68. We detected no significant heterogeneity between trials: I2=32% and τ2=0.007.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of differences in pain intensity expressed as effect size (standardised mean difference) at 12 weeks (8 trials).

Effect on joint function

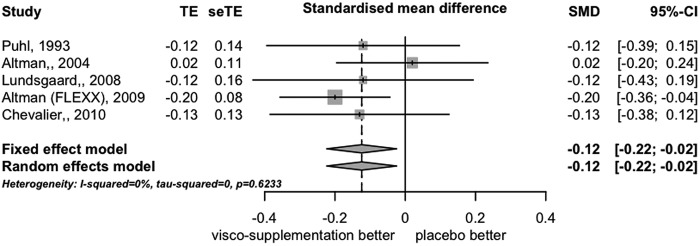

Five trials contributed to the MA of function-related outcomes. The SMD was −0.12 (95% CI −0.22 to −0.02), which corresponds to an OR of 0.80; we found no heterogeneity among trials (I2=0% and τ2=0.0) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of differences in function expressed as effect size (standardised mean difference) at 12 weeks (5 trials).

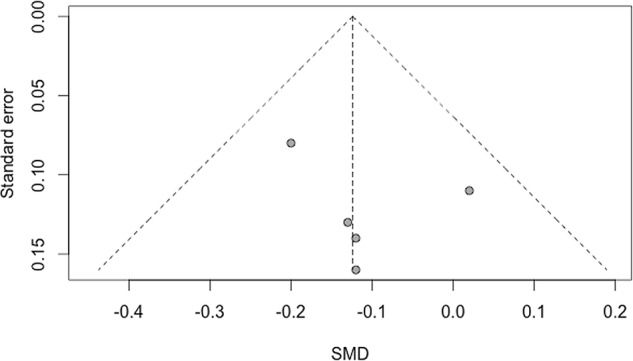

Risk of bias across studies

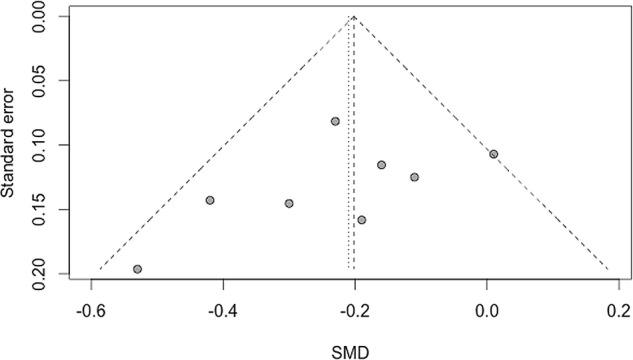

We found no evidence of bias across trials for pain and function outcomes (figures 4 and 5, respectively).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot of standardised mean difference (SMD) for pain intensity.

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of standardised mean difference (SMD) for physical function.

Discussion

The findings from our systematic review and MA restricted to high-quality trials of IAHA versus placebo additionally contribute to the debate on the efficacy of IAHA for KOA. We found an effect size (SMD) for pain of 0.21, which is moderate but clinically relevant on an individual patient basis according to the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) consensus.33

Several reviews and MAs examining the effects of IAHA have produced divergent results.14 15 34–40 Most MAs (n=7) found HA to be more effective than placebo or marginally effective, and only two studies found that HA did not differ from placebo.38 39

One explanation for this discrepancy could be differences in the trials pooled and the data extracted for the MA. From the 89 clinical trials potentially eligible for our review, only eight were at low risk of bias and thus included in our study. Most of our RCTs of IAHA did not fulfil the criteria for a high-quality trial, as was previously found.14 15 Pitfalls were mainly related to inadequate randomisation, inadequate concealment and inadequate blinding of patients, which are frequent in trials assessing non-pharmacological treatments of OA.41 42

Since low-quality studies might bias the MA itself, we conducted an MA of high-quality trials and prespecified criteria. We chose these criteria according to an explanatory analysis of subgroups15 and results of meta-epidemiological studies:18 19 adequate random sequence, concealment of treatment and blinding of patients and outcome assessment.

In directly comparing results from our eight trials,25–32 the SMD for pain at 3 months was −0.20 (95% CI −0.12 to −0.29; fixed-effects model) and −0.21 (−0.10 to −0.32; random-effects model), with I²=32%, τ2=0.0072. These estimates for pain are lower than that reported by Rutjes et al15 (effect size (ES)=0.37 (95% CI 0.28 to 0.46; τ=0.09; Egger test <0.001), who analysed 71 trials. In contrast, our results are close to those reported by Bannuru et al14 (ES for pain −0.29, −0.22 and 0.20 at 12, 16 and 24 weeks, respectively), who restricted their analysis to high-quality trials defined as those with more than 100 randomised participants and reporting intention-to-treat analyses, adequate blinding and allocation concealment.

A global analysis of previously published MAs34–40 showed an ES for IAHA for pain with KOA at 3 months between 0.20 and 0.30. Of note, these estimates are greater than that for acetaminophen (ES=−0.13, 95% CI −0.22 to −0.04),7 a drug recommended by the OARSI6 and the ACR.13 A recent MA comparing the relative efficacy of IAHA and NSAIDs in KOA concluded equal effectiveness of both treatments in alleviating pain at 4 and 12 weeks.43

Given the chronicity of pain in OA and the common presence of cardiovascular comorbidities, the benefits and risks of drugs given for this condition must be carefully weighed. Rutjes et al15 found that HA can increase the risk of serious adverse events. However, these findings, never reported in an MA, have raised severe criticism in terms of the methodology used to assess HA safety.44 45 Therefore, given the limited range of available treatments for KOA and the frequency of comorbidities, IAHA may be an appropriate therapeutic option for patients who fail to respond to oral treatments.

The limitations to our MA include the potential for publication bias. Indeed, we included only published trials and therefore cannot exclude that inclusion of some small, negative, non-published studies might have biased our results.46 47 In addition, it should be noted that our time point assessment was 3 months, which can be considered a short period of time. In addition, this MA assessed the efficacy of HA as a whole, and did not distinguish separately the different type of HA.

In conclusion, this MA of RCTs of IAHA versus placebo for KOA, with a low risk of bias, shows that IAHA may have a moderate but real benefit for patients with KOA. Given the paucity of well-tolerated effective treatments and the well-known toxicity of NSAIDs, IAHA should be considered to alleviate pain and improve function, in particular for patients with comorbidities.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Laura Smales for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: PR, MM and MC conceived the study and interpreted the data. The manuscript was written by PR and MM. XC, HKE, FE, YH, PO and JS revised it critically and provided substantial changes. MC and MM performed the statistical analysis.

Funding: This study was funded by Affinité Santé (CRO). The funder was not involved in the design, implementation, results and writing of this study.

Competing interests: PR received fees from BioIbérica, Fidia, IBSA, Expanscience, Genévrier, Sanofi, Rottapharm, Servier, Flexion Therapics and Ménarini. XC received fees from Flexion therapics, Moebius, Sanofi and Genévrier. . YH is the founder and chairman of Synolyne Pharma. He received speaker fees from IBSA, BioIberica, Tilman SA and Expanscience. PO received fees from Génévrier and Rottapharm. JS received fees from Expanscience, TRB Chemedica and Servier. MC received fees from Affinités Santés. MM received fees from Pierre Fabre, ChromaPharma, TRB Chemedica, Genévrier, Rottapharm, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ferring, Bioventus and Sanofi.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1323–30. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochberg MC. Mortality in osteoarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2008;26:S120–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuesch E, Dieppe P, Reichenbach S et al. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. BMJ 2011;342:d1165 10.1136/bmj.d1165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson VL, Hunter DJ. The epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2014;28:5–15. 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhala N, Emberson J, Merhi A et al. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2013;382:769–79. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60900-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Judd MG et al. Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD004257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richette P. How safe is acetaminophen in rheumatology? Joint Bone Spine 2014;81:4–5. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:137–62. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1145–55. 10.1136/ard.2003.011742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.No authors listed]. Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1905–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jevsevar DS, Brown GA, Jones DL et al. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons evidence-based guideline on: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee, 2nd edition. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:1885–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:465–74. 10.1002/acr.21596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bannuru RR, Natov NS, Dasi UR et al. Therapeutic trajectory following intra-articular hyaluronic acid injection in knee osteoarthritis—meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:611–19. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rutjes AW, Juni P, da Costa BR et al. Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:180–91. 10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 2001;323:42–6. 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ et al. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273:408–12. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520290060030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz KF. Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;274:1456–8. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530180050029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DerSimonian R, Charette LJ, McPeek B et al. Reporting on methods in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 1982;306:1332–7. 10.1056/NEJM198206033062204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furukawa TA. From effect size into number needed to treat. Lancet 1999;353:1680 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01163-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med 2000;19:3127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shichikawa K, Maeda A, Ogawa N. [Clinical evaluation of sodium hyaluronate in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee]. Ryumachi 1983;23:280–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puhl W, Bernau A, Greiling H et al. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate in osteoarthritis of the knee: a multicenter, double-blind study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1993;1:233–41. 10.1016/S1063-4584(05)80329-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altman RD, Akermark C, Beaulieu AD et al. Efficacy and safety of a single intra-articular injection of non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12:642–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman RD, Rosen JE, Bloch DA et al. A double-blind, randomized, saline-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of EUFLEXXA for treatment of painful osteoarthritis of the knee, with an open-label safety extension (the FLEXX trial). Semin Arthritis Rheum 2009;39:1–9. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2009.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrella RJ, Petrella M. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of intraarticular hyaluronic acid for osteoarthritis of the knee. J Rheumatol 2006;33:951–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lundsgaard C, Dufour N, Fallentin E et al. Intra-articular sodium hyaluronate 2mL versus physiological saline 20mL versus physiological saline 2mL for painful knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. Scand J Rheumatol 2008;37:142–50. 10.1080/03009740701813103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navarro-Sarabia F, Coronel P, Collantes E et al. A 40-month multicentre, randomised placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and carry-over effect of repeated intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid in knee osteoarthritis: the AMELIA project. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1957–62. 10.1136/ard.2011.152017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chevalier X, Jerosch J, Goupille P et al. Single, intra-articular treatment with 6ml hylan G-F 20 in patients with symptomatic primary osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:113–19. 10.1136/ard.2008.094623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21. 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang CT, Lin J, Chang CJ et al. Therapeutic effects of hyaluronic acid on osteoarthritis of the knee. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A:538–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V et al. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(2):CD005321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo GH, LaValley M, McAlindon T et al. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2003;290:3115–21. 10.1001/jama.290.23.3115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modawal A, Ferrer M, Choi HK et al. Hyaluronic acid injections relieve knee pain. J Fam Pract 2005;54:758–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arrich J, Piribauer F, Mad P et al. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2005;172:1039–43. 10.1503/cmaj.1041203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medina JM, Thomas A, Denegar CR. Knee osteoarthritis: should your patient opt for hyaluronic acid injection? J Fam Pract 2006;55:669–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller LE, Block JE. US-approved intra-articular hyaluronic acid injections are safe and effective in patients with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, saline-controlled Trials. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 2013;6:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marty M. The specific challenge to conduct high quality trials assessing non pharmacological treatments of osteoarthritis. In: Henrotin Y, Bennell K, Rannou F eds. Nonpharmacological therapies in the management of osteoarthritis. Bentham Science Publishers, 2012:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boutron I, Tubach F, Giraudeau B et al. Methodological differences in clinical trials evaluating nonpharmacological and pharmacological treatments of hip and knee osteoarthritis. JAMA 2003;290:1062–70. 10.1001/jama.290.8.1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bannuru RR, Vaysbrot EE, Sullivan MC et al. Relative efficacy of hyaluronic acid in comparison with NSAIDs for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;43:593–9. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR. Osteoarthritis: is viscosupplementation really so unsafe for knee OA? Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8:635–6. 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruyere O, Cooper C, Pelletier JP et al. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: a report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;44(3):253–63. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dwan K, Gamble C, Williamson PR et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias—an updated review. PLoS ONE 2013;8: e66844 10.1371/journal.pone.0066844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kicinski M. Publication bias in recent meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e81823 10.1371/journal.pone.0081823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]