Abstract

Pericardiocentesis (PC) is both a diagnostic and a potentially life-saving therapeutic procedure. Currently echocardiography-guided pericardiocentesis is considered the standard clinical practice in the treatment of large pericardial effusions and cardiac tamponade. Although considered relatively safe, this invasive procedure may be associated with certain risks and potentially serious complications. This review provides a summary of pericardiocentesis and a focused overview of the potential complications of this procedure.

Keywords: Bedside procedure, complications, pericardiocentesis, review, ultrasound guidance

INTRODUCTION

Pericardiocentesis (PC) was first described in 1653 by Riolanus, who outlined the trephination of the sternum to relieve fluid surrounding the heart.[1] The “blind” approach to PC used in the past, failed to gain wide support due to high morbidity, with serious or life-threatening complications exceeding 20% and mortality approaching 6%.[2,3,4] However, with the development of ultrasound-guided techniques in the 1970s, PC has become essential in the diagnosis and management of most hemodynamically significant pericardial effusions.[5] Ultrasound-guided diagnostic and therapeutic PC is currently considered the standard clinical practice in the treatment of pericardial effusions.[6] The procedure can be performed safely in an outpatient setting for carefully selected, stable patients.[7] It is well-tolerated in all age groups, including children,[8] and can be performed quickly in unstable patients[9] to relieve symptoms of pericardial tamponade.[10] In significant pericardial effusions, echocardiography-guided PC has high success rates of >95% with relatively little risk [Figure 1]. The morbidity rate is approximately 1–3% and the mortality rate from injuries directly caused by the procedure is less than 1%.[2]

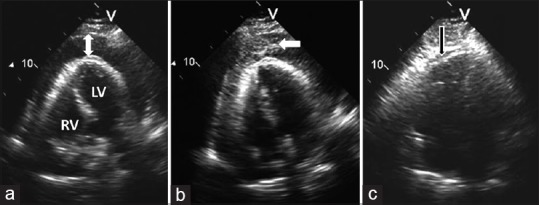

Figure 1.

Ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis in a patient with malignant pericardial effusion and tamponade. (a) Apical view of the heart showing large circumferential pericardial effusion (arrow); (b) Intrapericardial injection of agitated saline (whitish-gray cloud of microbubbles of air) verifies correct positioning of the pericardiocentesis needle (arrow); and (c) following pericardiocentesis, the right ventricle has expanded and no residual pericardial effusion is seen within the pericardial sac (arrow). LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle

Despite the standardization of PC, there is no comprehensive literature review summarizing all known complications associated with this procedure. Thus, our group performed a comprehensive search of global medical literature on this topic, including cross-referenced, non-indexed articles. We present a detailed review of the complications of PC, including relevant topics such as procedural indications, anatomic considerations, and preventive strategies.

ETIOLOGIES OF PERICARDIAL EFFUSION

The etiologies of pericardial effusions requiring intervention have changed over time. Historically, the most common causes of pericardial effusions were malignancy and uremia.[6] Pericardial effusions secondary to tuberculosis were more prevalent among the economically disadvantaged patients, and hospitals caring for underserved populations.[11] Recent studies indicate that pericardial effusions occurring as a complication of percutaneous catheter-based procedures are increasing.[12,13,14,15,16] The incidence of cardiac perforation is 1.5–4.7% for valvuloplasty,[15,17] 0.2–1% for radiofrequency ablation,[18,19] 0.1–0.2% for electrophysiological study,[20,21] 0.03% for coronary angioplasty,[22] 0.5% for cardiac biopsy,[23] and 0.01% for diagnostic catheterization.[15] Potentially fatal complications such as iatrogenic right and left ventricular perforation have also been reported.[24,25]

The increase in numbers of iatrogenic pericardial effusions from catheter-based procedures accounts for the significant percentage of PCs being performed in patients on anticoagulant therapy.[13] This alone may have a significant effect on the overall risk associated with the procedure. Approximately half of patients who underwent PC had taken an anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent the same day.[13] Patients undergoing catheter-based procedures may be at higher risk for presenting acutely with overt tamponade because they are more likely to be receiving antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents for existing cardiovascular disease. Studies show that over 95% of patients requiring PC after a cardiac intervention received at least one anticoagulant or antiplatelet agent on the day of the procedure. A significant proportion of such patients received up to 3 or more of such agents.[13] As expected, anticoagulation is a relative contraindication to performing PC per the European Cardiology Society guidelines and may have an impact on the risk profile and complication rate associated with PC.[11]

Ho et al.,[26] showed that PC performed for pericardial effusion post catheter-based cardiac intervention is associated with higher rates of acute complications when compared to other causes of pericardial effusion. These differences may be explained by variations in the volume of pericardial effusions and the acuity of tamponade development. Large volume effusions have a greater pericardial space available for needle insertion, with suggested effusion size of >20 mm prior to drainage in the absence of an acute tamponade.[27] In addition, acute iatrogenic pericardial effusion and tamponade is hemorrhagic in nature and the fluid is indistinct from blood in cardiac chambers. This would significantly reduce the certainty of positioning of the PC needle tip in the correct location. Thus, there is a lower risk of injuring surrounding structures when draining a large, chronic, serous or serosanguineous pericardial effusions compared to a small, acute hemorrhagic effusions.[26] Larger, malignant chronic effusions tend to be recurrent, and may require repeat intervention.[26]

PROCEDURAL INDICATIONS

The primary indication for PC is cardiac tamponade, accounting for >80% of PC procedures.[28,29] Cardiac tamponade is a class I indication for PC according to the European Society of Cardiology guidelines for management of pericardial diseases.[30] A large (>20 mm) pericardial effusion may also be considered for PC (Class IIa recommendation),[30] particularly for diagnostic purposes. Relative indications for drainage based on echocardiography findings include the following: (a) right atrial and/or right ventricular collapse in diastole, or (b) development of a large effusion in less than 1 month.[27] PC is not typically performed when an effusion is noted to be resolving on its own or less invasive methods can be used to make the diagnosis and treat the source of the effusion.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Aortic dissection, myocardial rupture, and traumatic effusion with hemodynamic instability are all contraindications for PC[30] and warrant immediate surgical correction[10] [Figure 2]. PC can only act as a temporizing measure in the event that the patient decompensates en route to the operating room. Other relative contraindications include uncorrected coagulopathy, concurrent or active anticoagulant therapy, and thrombocytopenia (platelet count of <50).[31] Relative contraindications can be reevaluated on a case-by-case basis for special considerations, including acute or symptomatic tamponade and anticipated hemodynamic collapse. Inaccessible (e. g., loculated posterior collections), presence of extensive adhesions, and purulent pericardial effusions are other potential contraindications to PC.

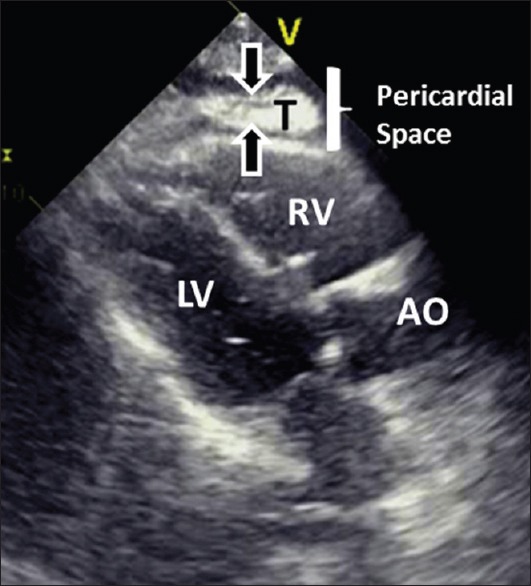

Figure 2.

Intrapericadial hematoma in a patient with acute myocardial infarction and cardiac rupture. The thrombus (T) is shown as an echogenic mass inside the pericardial space. Immediate transfer to operating room for relief of tamponade and repair of the ruptured myocardium can be life-saving. AO = aorta; LV = left ventricle; RV = right ventricle

INFORMED CONSENT

Universal procedural precautions, patient verification and identification protocols should be used when circumstance allows.[32] PC may be performed under implied consent when used in life-saving circumstances. However, a formal informed consent should be obtained in less emergent settings. Despite potentially serious complications, one U. K. study demonstrated that only half of the PCs performed in a series of patients had evidence of written consent in the medical notes.[30]

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

The pericardial sac is a double-walled membrane that surrounds the heart and is located in the middle mediastinum along with the ascending aorta, pulmonary trunk, superior vena cava, azygos vein and main bronchi. It extends from the fifth to the eight thoracic vertebrae, posterior to the sternum and between the second to sixth costal cartilages.[33] Table 1 describes the three possible approaches for draining pericardial effusions. In general, the anatomic approach to PC is dictated by the location of the largest collection of fluid and the ease of percutaneous access.

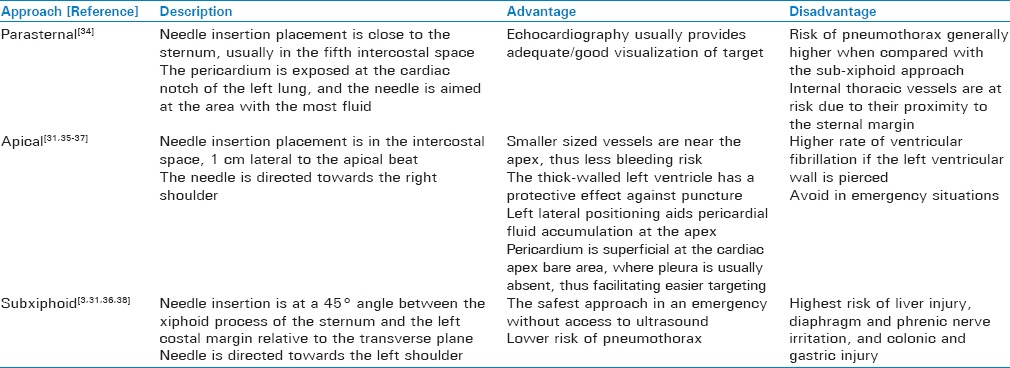

Table 1.

Outline of described pericardiocentesis approaches

OVERVIEW OF COMPLICATIONS

Subsequent sections will discuss more frequent complications of PC including rates, severity, and other important procedural and non-procedural considerations. Major complications (incidence 1-2%) include mortality, cardiac arrest, cardiac perforation leading to tamponade, pericardial/epicardial thrombus, cardiac chamber laceration requiring surgery, injury to an intercostal vessel, pneumothorax requiring chest tube placement, ventricular tachycardia, pulmonary edema and local/systemic infection.[14,24,37,39,40] Minor complications include small pneumothorax, vasovagal response with transient hypotension, non-sustained supraventricular tachycardia, pericardial catheter occlusion, and pleuropericardial fistula.[14,37] Mortality associated with ultrasound-guided PC is low (<1%) and the overall complication rate may vary between 4% and 20%.[3,4,14,36,41,42] These complications will now be discussed, focusing on signs/symptoms, diagnostic considerations, and clinical management. An overview of pericardiocentesis complications is provided in Table 2.

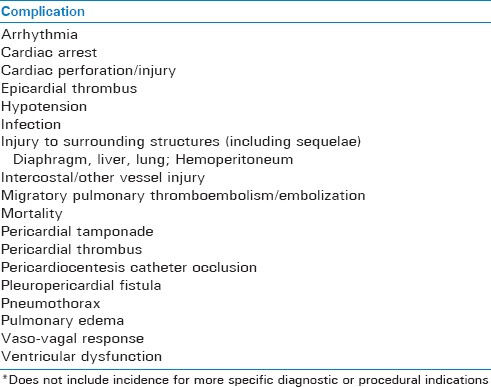

Table 2.

Overview of reported complications of pericardiocentesis (alphabetical)

Cardiac perforation/Iatrogenic tamponade

The cardiac perforation rate is approximately 1%. In studies evaluating catheter-based pericardial effusions presenting with tamponade, approximately half presented while patients were still at the medical facility where PC was performed, while the remaining half developed after leaving the medical facility.[8,43,44] The median presentation time was 5 hours.[8,43,44] Because of the very real possibility of late presentation, especially following a catheter-based procedure, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for this complication. Although the optimal duration of such post-procedural monitoring has not been clearly defined, the authors of this report recommend and observation period of 4–6 hours for asymptomatic patients and 6–24 hours for those who exhibit any form of post-procedural symptoms (depending on symptom duration and resolution).

The so-called “rescue pericardiocentesis” for pericardial effusion has also been associated with the development of intrapericardial and subepicardial thrombi in adult and pediatric patients due to cardiac puncture.[40,45,46] Several findings suggest an intrapericardial thrombus: (a) failure of symptom improvement following therapeutic PC; (b) detection of a new homogeneous, immobile mass attached to the epicardium with extension into the parietal pericardium; and (c) new crescent-shaped echogenic density on 2-D-echogardiography.[45,46] Detection of intrapericardial thrombus following PC on non-hemorrhagic effusion suggests cardiac puncture.[45] This can be further supported by: (a) new ST-segment elevation (current of injury) on electrocardiogram; (b) rapid clotting of aspirated fluid; (c) identical dye dilution curves obtained from injection of indocyanine green through a PC needle and via intravenous catheter; and (d) similar values of hematocrit, PO2, PCO2, pH, and bicarbonate of the aspirated fluid and arterial blood.[14,47,48,49]

Hemodynamic derangement

Hemodynamic derangement can arise from ventricular dysfunction (VD) as a complication of PC. Reported spectrum of clinical manifestations includes cardiogenic shock,[50] cardiogenic pulmonary edema,[51] and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema,[52] all of which can develop within hours to several days after the procedure.[53] Pericardiocentesis may also contribute to profound hypoxia or right ventricular dilation, with subsequent cardiopulmonary failure.[53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]

Pericardial decompression syndrome

Pulmonary edema following PC for cardiac tamponade can be life threatening.[63] Although infrequent, it is by no means rare. Pulmonary edema occurs primarily as a consequence of paradoxical left ventricular dysfunction post-PC.[39] This is a well-defined clinical entity that mechanistically is yet to be fully explained. Various pathophysiologic mechanisms have been suggested, including considerations discussed in this section and other parts of this review.

Manyari et al.,[64] studied this phenomenon specifically in post-PC patients. The authors used equilibrium gated radionuclide ventriculography immediately before and after PC in 10 patients (of whom 5 had cardiac tamponade). In patients with tamponade, right ventricular end-diastolic volume increased more than left ventricular end-diastolic volume (72% vs. 56%) following PC.[64] Although the study did not evaluate change in right ventricular stroke volume, the measured increase in right ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes represented a 76% increase in right ventricular stroke volume, significantly higher than the calculated 64% increase in left ventricular stroke volume. This imbalance may help explain the rapid increase in pulmonary vascular and left atrial volumes as well as an abrupt increase in the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, contributing to the development of pulmonary edema.[64]

The pericardial decompression syndrome is heterogeneous in presentation and does not seem to be specifically associated with any particular cause of pericardial effusion. It has been associated with both surgical pericardiostomy and pericardiocentesis. Finally, it has been described in various literature sources under different names, including “pulmonary edema,” “ventricular dysfunction or failure,” and “low cardiac output syndrome.” The use of the term “pericardial decompression syndrome” is an attempt to simplify nomenclature and focus on commonalities between the above-listed pathologic states.[52,63,64,65,66]

Pneumopericardium

Another important complication of PC is pneumopericardium, or the presence of air along with fluid in the pericardial sac. This develops when a direct communication between pleura and pericardium forms, air is introduced during the aspiration procedure, or when there is a leak in the drainage system.[67,68,69,70,71] Chest radiograph is the best initial study of choice, demonstrating a wide separation of the pericardium from the heart. Other studies include transthoracic echocardiography, which shows bubbles “swirling” around the heart,[72] and computed tomography, which can confirm air and fluid in the pericardial sac. Close monitoring is typically sufficient for the majority of cases of post-PC pneumopericardium, which is a self-limited phenomenon that tends to resolve spontaneously. However, in patients with hemodynamic instability and accompanying pericardial effusion, repeated PC is the treatment of choice. Careful procedural technique that minimizes air entry into the drainage catheter is crucial to prevent such a complication.[67,68,69,70,71,73]

Cardiac arrhythmia and vasovagal reaction

Pericardiocentesis has been associated with complications such as vasovagal reaction, transient arrhythmia, sinus node dysfunction, and transient or persistent ST- or PR-segment elevation.[74,75,76] ST-or PR-segment elevation has been used as a monitoring technique for the detection of inadvertent myocardial injury, but myocardial laceration without associated EKG changes is not uncommon.[76] Persistent ST-elevation post-PC requires special attention as it may reflect subepicardial injury commonly seen in acute coronary occlusion due to thrombosis or vasospasm. Post-PC persistent ST-elevation should warrant additional investigation for myocardial or coronary artery injury using either echocardiography or in some cases coronary arteriography before initiating treatment of ischemia, especially in the setting of potential thrombosis.[37,74,75,76,77]

Iatrogenic injury to surrounding structures

Erroneous introduction/excursion of the PC drainage catheter can result in superior vena cava perforation, transhepatic perforation of the hepatic veins, as well as IVC and right atrial perforation/injury.[78] The subxiphoid approach can also cause intraprocedural injury to the diaphragm, the phrenic nerve, liver, colon and stomach.[79,80] These complications highlight the very real potential for adverse sequelae associated with PC. It has been recommended that experienced clinicians should perform these procedures with a cardiothoracic unit available in the event of a major complication.[79,80]

MISCELLANEOUS COMPLICATIONS AND TOPICS

Migratory pulmonary thromboembolism/embolization

Extremely rare complications of PC include the potentially fatal migratory pulmonary thromboembolism and shearing and embolization of the outer coat of the guidewire. An abrupt increase in venous return following PC in at-risk patients may result in migration of deep venous thrombus and fatal pulmonary embolism.[81,82]

Hemorrhagic peritonitis/hemoperitoneum

The literature describes hemoperitoneum and hemorrhagic peritonitis following the subxiphoid approach.[83,84] More specifically, perforation of the diaphragm or peritoneum during PC in the setting of anticoagulation can result in clot dislodgment from the diaphragm puncture site, potentially causing subsequent hemorrhagic peritonitis and hemoperitoneum.[83,84]

COMPLICATIONS OF PERICARDIAL ACCESS IN ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY

Recent advances in cardiac electrophysiology include the successful radiofrequency ablation of ventricular tachycardias (VT). While initially all ablations were endocardial, the last decade has seen the rise of epicardial ablations. Originally done to treat VT from Chagas disease this has become a great tool in the treatment of non-ischemic cardiomyopathies, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasias and even in some cases of ischemic cardiomyopathies. It is also useful in ablation of select supra-ventricular arrhythmias.[85,86,87] Since the procedure involves gaining a dry pericardial access, with no pericardial effusion in between, it is technically demanding and carries its own set of complications. Injury to myocardium, right ventricular puncture and damage to epicardial vessels can occur during access. Other injuries related to access, catheter manipulation and ablation are also well described and can affect any of the surrounding structures including the phrenic nerve, lungs, or the esophagus.[88,89,90,91] As experience with these procedures has increased, practitioners have learned to perform access in various high-risk populations groups - patients who are obese, those with prior coronary artery bypass surgery, those on heparin, and those with history of non-coronary cardiac procedures.[92,93,94,95] Another recent development includes the use of various atrial-appendage closure devices many of which require an epicardial access. This carries risks similar to those of epicardial access during ablation.[96]

RECENT PROCEDURAL ADVANCEMENTS

Strategies such as continuous ECG monitoring, fluoroscopy, and echocardiography guidance during PC have greatly reduced complication rates compared to those in blind manipulations. However, the risks and complications of PC described in this paper are still very much real and prevalent. Recent advancements introduced to reduce procedure-related complications are as follows: (a) PC with a visual puncture system; (b) Echocardiography-guided PC with a probe-mounted needle; and (c) administration of agitated saline after needle insertion into the pericardial space to avoid entering a ventricular cavity or other undesired space.[3,5,97] In the future, guidelines regarding the rate and volume of pericardial fluid removal could help prevent some of the complications discussed herein, particularly in patients with pre-existing ventricular pathology.

CONCLUSION

Pericardiocentesis can be a potentially life-saving procedure. It has both diagnostic and therapeutic relevance and can be performed at relatively low risk. Complications associated with PC are rare, but can be severe and even life-threatening. The frequency, nature, and severity of complications can vary markedly depending on exact procedural indications and patient-specific risk factors. For smaller, acute pericardial effusions, techniques such as fluoroscopy, a visual puncture system, or other means of image-directed guidance may be necessary. With careful patient selection, taking into consideration the etiology, volume, and location of the pericardial effusion, the risks of PC can be further minimized.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Loukas M, Walters A, Boon JM, Welch TP, Meiring JH, Abrahams PH. Pericardiocentesis: A clinical anatomy review. Clin Anat. 2012;25:872–81. doi: 10.1002/ca.22032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen CT, Lee E, Luo H, Siegel RJ. Echocardiographic guidance for diagnostic and therapeutic percutaneous procedures. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2011;1:11–36. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2011.09.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ainsworth CD, Salehian O. Echo-guided pericardiocentesis: Let the bubbles show the way. Circulation. 2011;123:e210–1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.005512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kil UH, Jung HO, Koh YS, Park HJ, Park CS, Kim PJ, et al. Prognosis of large, symptomatic pericardial effusion treated by echo-guided percutaneous pericardiocentesis. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:531–7. doi: 10.1002/clc.20305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maggiolini S, Bozzano A, Russo P, Vitale G, Osculati G, Cantù E, et al. Echocardiography-guided pericardiocentesis with probe-mounted needle: Report of 53 cases. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2001;14:821–4. doi: 10.1067/mje.2001.114009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osranek M, Bursi F, O’Leary PW, Bruce CJ, Sinak LJ, Chandrasekaran K, et al. Hand-carried ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis and thoracentesis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:480–4. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(03)00080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drummond JB, Seward JB, Tsang TS, Hayes SN, Miller FA., Jr Outpatient two-dimensional echocardiography-guided pericardiocentesis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1998;11:433–5. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(98)70022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsang TS, El-Najdawi EK, Seward JB, Hagler DJ, Freeman WK, O’Leary PW. Percutaneous echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis in pediatric patients: Evaluation of safety and efficacy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1998;11:1072–7. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(98)70159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsang TS, Freeman WK, Barnes ME, Reeder GS, Packer DL, Seward JB. Rescue echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis for cardiac perforation complicating catheter-based procedures. The Mayo Clinic experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1345–50. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitch MT, Nicks BA, Pariyadath M, McGinnis HD, Manthey DE. Videos in clinical medicine. Emergency pericardiocentesis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:e17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm0907841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbs CR, Watson RD, Singh SP, Lip GY. Management of pericardial effusion by drainage: A survey of 10 years’ experience in a city centre general hospital serving a multiracial population. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:809–13. doi: 10.1136/pmj.76.902.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abramov D, Tamariz MG, Fremes SE, Guru V, Borger MA, Christakis GT, et al. Trends in coronary artery bypass surgery results: A recent, 9-year study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:84–90. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inglis R, King AJ, Gleave M, Bradlow W, Adlam D. Pericardiocentesis in contemporary practice. J Invasive Cardiol. 2011;23:234–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsang TS, Enriquez-Sarano M, Freeman WK, Barnes ME, Sinak LJ, Gersh BJ, et al. Consecutive 1127 therapeutic echocardiographically guided pericardiocenteses: Clinical profile, practice patterns, and outcomes spanning 21 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:429–36. doi: 10.4065/77.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedrich SP, Berman AD, Baim DS, Diver DJ. Myocardial perforation in the cardiac catheterization laboratory: Incidence, presentation, diagnosis, and management. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;32:99–107. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810320202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baim DS, Diver DJ, Feit F, Greenberg MA, Holmes DR, Weiner BH, et al. Coronary angioplasty performed within the thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction II study. Circulation. 1992;85:93–105. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isner JM. Acute catastrophic complications of balloon aortic valvuloplasty. The Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1436–44. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Complications of radiofrequency ablation: A French experience. Le Groupe de Rythmologie de la Societe Francaise de Cardiologie. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1996;89:1599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lesh MD, Van Hare GF, Schamp DJ, Chien W, Lee MA, Griffin JC, et al. Curative percutaneous catheter ablation using radiofrequency energy for accessory pathways in all locations: Results in 100 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:1303–9. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90338-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horowitz LN. Safety of electrophysiologic studies. Circulation. 1986;73:II28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vignati G, Bruschi G, Mauri L, Annoni G, Frigerio M, Martinelli L, et al. Percutaneous device closure of iatrogenic left ventricular wall pseudoaneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:e31–3. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seggewiss H, Schmidt HK, Mellwig KP, Everlien M, Strick S, Fassbender D, et al. Acute pericardial tamponade after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). A rare life threatening complication. Z Kardiol. 1993;82:721–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deckers JW, Hare JM, Baughman KL. Complications of transvenous right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy in adult patients with cardiomyopathy: A seven-year survey of 546 consecutive diagnostic procedures in a tertiary referral center. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:43–7. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90049-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunishige H, Ishbashi Y, Kawasaki M, Yamakawa T. Surgical treatment of iatrogenic cardiac injury induced by pericardiocentesis; report of a case. Kyobu Geka. 2011;64:419–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hangalapura BN, Kaiser MG, Poel JJ, Parmentier HK, Lamont SJ. Cold stress equally enhances in vivo pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression in chicken lines divergently selected for antibody responses. Dev Comp Immunol. 2006;30:503–11. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho MY, Wang JL, Lin YS, Mao CT, Tsai ML, Wen MS, et al. Pericardiocentesis adverse event risk factors: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Cardiology. 2015;130:37–45. doi: 10.1159/000368796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006;113:1622–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.561514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balmain S, Hawkins NM, MacDonald MR, Dunn FG, Petrie MC. Pericardiocentesis practice in the United Kingdom. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1515–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy CL, Minor MA, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK. Does this patient with a pericardial effusion have cardiac tamponade? JAMA. 2007;297:1810–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.16.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maisch B, Seferoviæ PM, Ristiæ AD, Erbel R, Rienmüller R, Adler Y, et al. Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pricardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:587–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clarke DP, Cosgrove DO. Real-time ultrasound scanning in the planning and guidance of pericardiocentesis. Clin Radiol. 1987;38:119–22. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(87)80005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwiatt M, Tarbox A, Seamon MJ, Swaroop M, Cipolla J, Allen C, et al. Thoracostomy tubes: A comprehensive review of complications and related topics. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2014;4:143–55. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.134182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore KL, Agur AM. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. Dalley AF Essential clinical anatomy; pp. 692–693. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsang TS, Freeman WK, Sinak LJ, Seward JB. Echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis: Evolution and state-of-the-art technique. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:647–52. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)64888-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Last RJ. Edinburgh Lothian. 7th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1984. Anatomy, regional and applied; p. xxiv. 612. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Treasure T, Cotter L. How to aspirate the pericardium. Br J Hosp Med. 1980;24:488–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong B, Murphy J, Chang CJ, Hassenein K, Dunn M. The risk of pericardiocentesis. Am J Cardiol. 1979;44:1110–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(79)90176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrahams PH, Webb PJ. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1975. Clinical anatomy of practical procedures; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vandyke WH, Jr, Cure J, Chakko CS, Gheorghiade M. Pulmonary edema after pericardiocentesis for cardiac tamponade. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:595–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198309083091006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meliones JN, Snider AR, Beekman RH, Bengur AR, Bogaards MA. Echocardiographic detection of pericardiocentesis-induced subepicardial and intramyocardial hematoma. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:820–1. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90776-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buchanan CL, Sullivan VV, Lampman R, Kulkarni MG. Pericardiocentesis with extended catheter drainage: An effective therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:817–20. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00666-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duvernoy O, Borowiec J, Helmius G, Erikson U. Complications of percutaneous pericardiocentesis under fluoroscopic guidance. Acta Radiol. 1992;33:309–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fejka M, Dixon SR, Safian RD, O’Neill WW, Grines CL, Finta B, et al. Diagnosis, management, and clinical outcome of cardiac tamponade complicating percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1183–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02831-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Outcomes of clinically significant idiopathic pericardial effusion requiring intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:704–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin CS, Jan YI, Chen HY, Hou SH, Kuo CC. Two-dimensional echocardiographic detection of pericardiocentesis-induced intrapericardial thrombus. Chest. 1984;86:787–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.86.5.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schuster AH, Nanda NC. Pericardiocentesis induced intrapericardial thrombus: Detection by two-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J. 1982;104:308–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zipes DP, Braunwald E. 7th ed. Philadelphia: W. B Saunders; 2005. Braunwald's heart disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine; p. xxi. 2183, 75. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stone JR, Martin RH. Bloody pericardial fluid or intracardiac blood? A method for quick and accurate differentiation. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:592–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mann W, Millen JE, Glauser FL. Bloody pericardial fluid. The value of blood gas measurements. JAMA. 1978;239:2151–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.239.20.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Braverman AC, Sundaresan S. Cardiac tamponade and severe ventricular dysfunction. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:442. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-5-199403010-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Downey RJ, Bessler M, Weissman C. Acute pulmonary edema following pericardiocentesis for chronic cardiac tamponade secondary to trauma. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:1323–5. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199110000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glasser F, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH, Cotton E, Niederman MS. Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema after pericardial drainage for cardiac tamponade. Chest. 1988;94:869–70. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.4.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ligero C, Leta R, Bayes-Genis A. Transient biventricular dysfunction following pericardiocentesis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:102–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sunderji I, Kuhl M, Mathew T. Post pericardiocentesis low cardiac output syndrome in a patient with malignant thymoma. BMJ Case Rep 2009. 2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.12.2008.1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolfe MW, Edelman ER. Transient systolic dysfunction after relief of cardiac tamponade. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:42–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-1-199307010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brauner FB, Nunes CE, Fabra R, Riesgo A, Thomé LG. Acute left ventricular systolic dysfunction after pericardial effusion drainage. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1997;69:421–3. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x1997001200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chamoun A, Cenz R, Mager A, Rahman A, Champion C, Ahmad M, et al. Acute left ventricular failure after large volume pericardiocentesis. Clin Cardiol. 2003;26:588–90. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960261209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Uemura S, Kagoshima T, Hashimoto T, Sakaguchi Y, Doi N, Nakajima T, et al. Acute left ventricular failure with pulmonary edema following pericardiocentesis for cardiac tamponade--a case report. Jpn Circ J. 1995;59:55–9. doi: 10.1253/jcj.59.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moreno Flores V, Pascual Figal DA, Caro Martínez C, Valdés-Chávarri M. Transient left ventricular dysfunction following pericardiocentesis. An unusual complication to bear in mind. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62:1071–2. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)73277-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aqel R, Dobbs J, Lau Y, Lloyd S, Gupta H, Zoghbi GJ. Transjugular biopsy of a right atrial mass under intracardiac echocardiographic guidance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:1072.e5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anguera I, Pare C, Perez-Villa F. Severe right ventricular dysfunction following pericardiocentesis for cardiac tamponade. Int J Cardiol. 1997;59:212–4. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(97)02918-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Armstrong WF, Feigenbaum H, Dillon JC. Acute right ventricular dilation and echocardiographic volume overload following pericardiocentesis for relief of cardiac tamponade. Am Heart J. 1984;107:1266–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90289-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karamichalis JM, Gursky A, Valaulikar G, Pate JW, Weiman DS. Acute pulmonary edema after pericardial drainage for cardiac tamponade. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:675–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Manyari DE, Kostuk WJ, Purves P. Effect of pericardiocentesis on right and left ventricular function and volumes in pericardial effusion. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:159–62. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bernal JM, Pradhan J, Li T, Tchokonte R, Afonso L. Acute pulmonary edema following pericardiocentesis for cardiac tamponade. Can J Cardiol. 2007;23:1155–6. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(07)70887-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skalidis EI, Kochiadakis GE, Chrysostomakis SI, Igoumenidis NE, Manios EG, Vardas PE. Effect of pericardial pressure on human coronary circulation. Chest. 2000;117:910–2. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.3.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Choi WH, Hwang YM, Park MY, Lee SJ, Lee HY, Kim SW, et al. Pneumopericardium as a complication of pericardiocentesis. Korean Circ J. 2011;41:280–2. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2011.41.5.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Delgado-Montero A, Carbonell A, Camino A, Jimenez-Mena M, Zamorano JL. An unexpected outcome after pericardiocentesis. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1845–6. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3048-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim HR, Choi D, Chung JW, Youn YN, Shim CY. Tension pneumopericardium after removal of pericardiocentesis drainage catheter. Cardiol J. 2009;16:477–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Methachittiphan N, Boonyaratavej S, Kittayarak C, Bhumimuang K, Mankongpaisarnrung C, Pinyoluksana KO, et al. Pneumohydropericardium with cardiac tamponade after pericardiocentesis. Heart. 2012;98:93. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mullens W, Dupont M, De Raedt H. Pneumopericardium after pericardiocentesis. Int J Cardiol. 2007;118:e57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yuce M, Sari I, Davutoglu V, Ozer O, Usalan C. Bubbles around the heart: Pneumopericardium 10 days after pericardiocentesis. Echocardiography. 2010;27:E115–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Slavich M, Briguglia D, Sacco FM, Lafelice I, Meloni C, Cianflone D. Occasional evidence of pneumopericardium after pericardiocentesis. G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2010;11:602–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bishop LH, Jr, Estes EH, Jr, McIntosh HD. The electrocardiogram as a safeguard in pericardiocentesis. J Am Med Assoc. 1956;162:264–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.1956.02970210004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cotoi S, Moldovan D, Caraºcã E, Incze A, Herszenyi L, Podoleanu D. Sinus node dysfunction occurring immediately after pericardiocentesis. Physiologie. 1987;24:63–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hsia HH, Kander NH, Shea MJ. Persistent ST-segment elevation following pericardiocentesis: Caution with thrombolytic therapy. Intensive Care Med. 1988;14:77–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00254130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gueron M, Hirsch M, Wanderman K. Letter: Myocardial laceration not shown by ECG during pericardiocentesis. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:938. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197510302931819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dabbah S, Fischer D, Markiewicz W. Pericardiocentesis ending in the superior vena cava. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;64:492–4. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knudson JD. Diseases of the pericardium. Congenit Heart Dis. 2011;6:504–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2011.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Emmert MY, Frauenfelder T, Falk V, Wilhelm MJ. Emergency pericardiocentesis: A word of caution! Accidental transhepatic intracardiac placement of a pericardial catheter. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:e31–2. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reddy SC, Kamath P, Talwar KK, Saxena A, Wasir HS. Guide wire outer coat shearing and embolisation: An unusual complication of pericardiocentesis. Int J Cardiol. 1997;60:15–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(97)02965-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Warsame TA, Yang HS, Mookadam F, Sorajja D, Den Y, Moustafa SE, et al. Fatal migratory pulmonary thromboembolism following successful pericardiocentesis. Echocardiography. 2010;27:E125–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bender F. Hemoperitoneum after pericardiocentesis in a CAPD patient. Perit Dial Int. 1996;16:330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luckraz H, Kitchlu S, Youhana A. Haemorrhagic peritonitis as a late complication of echocardiography guided pericardiocentesis. Heart. 2004;90:e16. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.024075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berte B, Yamashita S, Sacher F, Cochet H, Hooks D, Aljefairi N, et al. Epicardial only mapping and ablation of ventricular tachycardia: A case series. Europace. 2015 doi: 10.1093/europace/euv072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sarkozy A, Tokuda M, Tedrow UB, Sieria J, Michaud GF, Couper GS, et al. Epicardial ablation of ventricular tachycardia in ischemic heart disease. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:1115–22. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roberts-Thomson KC, Seiler J, Steven D, Inada K, Michaud GF, John RM, et al. Percutaneous access of the epicardial space for mapping ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias in patients with and without prior cardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:406–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lim HS, Sacher F, Cochet H, Berte B, Yamashita S, Mahida S, et al. Safety and prevention of complications during percutaneous epicardial access for the ablation of cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:1658–65. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Killu AM, Friedman PA, Mulpuru SK, Munger TM, Packer DL, Asirvatham SJ. Atypical complications encountered with epicardial electrophysiological procedures. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:1613–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koruth JS, Aryana A, Dukkipati SR, Pak HN, Kim YH, Sosa EA, et al. Unusual complications of percutaneous epicardial access and epicardial mapping and ablation of cardiac arrhythmias. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:882–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.965731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hsieh CH, Ross DL. Case of coronary perforation with epicardial access for ablation of ventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:318–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.09.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Killu AM, Ebrille E, Asirvatham SJ, Munger TM, McLeod CJ, Packer DL, et al. Percutaneous epicardial access for mapping and ablation is feasible in patients with prior cardiac surgery, including coronary bypass surgery. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:94–101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wan SH, Killu AM, Hodge DO, Packer DL, Mulpuru S, Asirvatham SJ, et al. Obesity does not increase complication rate of percutaneous epicardial access. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014;25:1174–9. doi: 10.1111/jce.12485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tschabrunn CM, Haqqani HM, Cooper JM, Dixit S, Garcia FC, Gerstenfeld EP, et al. Percutaneous epicardial ventricular tachycardia ablation after noncoronary cardiac surgery or pericarditis. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:165–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Page SP, Duncan ER, Thomas G, Ginks MR, Earley MJ, Sporton SC, et al. Epicardial catheter ablation for ventricular tachycardia in heparinized patients. Europace. 2013;15:284–9. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miller MA, Gangireddy SR, Doshi SK, Aryana A, Koruth JS, Sennhauser S, et al. Multicenter study on acute and long-term safety and efficacy of percutaneous left atrial appendage closure using an epicardial suture snaring device. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:1853–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu X, Feng Y, Xu G, Zhang Y, Qian J, Deng H, et al. A new strategy for pericardiocentesis with a visual puncture system: The feasibility and efficiency study in a pericardial effusion model. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:e128–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]