Abstract

Ultrasound scan of the spleen is an integral part of the overall abdominal examination. Due to its anatomical position, physical examination of the spleen is frequently supplemented with an ultrasound which plays a special role in the differential diagnostics of splenic diseases and facilitates the determination of further diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Similarly to other types of ultrasound scans, the examiner should be familiar with all significant clinical information as well as results of examinations and tests conducted so far. This enables to narrow the scope of search for etiological factors and indicate specific disease entities in the findings as well as allows for accurate assessment of coexistent pathologies. The article presents the standards of the Polish Ultrasound Society concerning the apparatus, preparation for the examination, technique and description of the findings. The authors discuss the normal anatomy of the spleen and the most common pathologies ranging from splenomegaly to splenic traumas. The indications for the contrast-enhanced ultrasound and characteristic patterns of enhancement of individual focal lesions are presented. This article is supplemented with photographic documentation, which provides images of the discussed lesions. The ultrasound examination, if carried out in compliance with current standards, allows for accurate interpretation of detected changes. This article has been prepared on the basis of the Ultrasound Examination Standards of the Polish Ultrasound Society (2011) and updated with the current knowledge.

Keywords: spleen ultrasound examination, standards of spleen ultrasound examination, splenic diseases, focal lesions of the spleen, splenic traumas

Abstract

Badanie ultrasonograficzne śledziony jest integralną częścią badania jamy brzusznej. Z uwagi na anatomiczne położenie badanie fizykalne śledziony często uzupełnia się badaniem ultrasonograficznym, odgrywającym szczególną rolę w diagnostyce różnicowej chorób śledziony, wyznaczającym kierunki dalszego postępowania diagnostycznego i terapeutycznego. Podobnie jak w przypadku innych rodzajów badań ultrasonograficznych, badający powinien mieć dostęp do wszystkich istotnych informacji klinicznych i wyników dotychczas wykonanych badań. Umożliwi to zawężenie obszaru poszukiwań czynników etiologicznych ze wskazaniem, w wyniku badania, na konkretne jednostki chorobowe i dokładną ocenę współistniejących patologii. W artykule przedstawiono standardy badania ultrasonograficznego śledziony Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego dotyczące aparatury, przygotowania do badania, jego techniki i opisu. Omówiono prawidłową budowę śledziony oraz jej najczęstsze zmiany patologiczne, zaczynając od splenomegalii, a kończąc na urazach śledziony. Przedstawiono wskazania do wykonania badania ultrasonograficznego z użyciem środków kontrastujących oraz omówiono charakterystyczne wzorce wzmocnienia poszczególnych zmian ogniskowych. Do pracy dołączono dokumentację zdjęciową, obrazującą omawiane zmiany. Wykonanie badań zgodnie z obowiązującymi standardami pozwala na optymalną ocenę narządu oraz prawidłową interpretację wykrytych zmian. Praca została przygotowana na podstawie publikacji pt. Standardy badań ultrasonograficznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego (2011) i uzupełniona o aktualne doniesienia.

Introduction

Ultrasound examination (US) is one of the first diagnostic examinations performed when abdominal symptoms appear. The US of the spleen is recommended to assess and monitor the size of the spleen in the course of various diseases, to diagnose uncharacteristic resistance in the left hypochondriac region as well as to assess posttraumatic changes. The correct interpretation of these pathologies is facilitated by clinical data including the results of the tests and examinations conducted so far.

Due to technological progress of ultrasound equipment, final diagnoses may be frequently established solely on the basis of the ultrasound scan without the need to perform further imaging examinations, including invasive ones. The evidence for the foregoing is provided in the clinical tests which say that ultrasound examinations conducted with the use of contrast agents (CEUS – contrast-enhanced ultrasound) give comparable results regarding sensitivity and specificity of detecting and determining the character of focal lesions in the spleen, to computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)(1). The EFSUMB (European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology) recommends the CEUS of the spleen in order to: 1) assess the character of the focal lesions in the spleen visualized in a standard US examination; 2) detect malignant focal lesions in oncological patients when the findings of other imaging examinations (CT, MRI) are unclear; 3) confirm the infarction of the spleen; 4) confirm the presence of accessory spleens (when focal lesions in the splenic hilum are detected)(1). CEUS examinations are also recommended in patients with abdominal trauma in order to exclude injuries of the spleen, in patients with little spleen to differentiate between asplenia and functional hyposplenia as well as to confirm abscesses and hematomas(2).

Apparatus

According to the standards of the Polish Ultrasound Society, the equipment for abdominal ultrasound examinations should meet the following requirements(3):

electronic convex broadband transducers with the frequency from 2 to 5 MHz. The examination is most frequently conducted with the convex probe of 3.5 MHz;

at least 128 transmit/receive channels;

display with the grey scale of 256 shades;

second harmonic imaging option;

color, pulsed and power Doppler;

the possibility to enlarge a frozen and real-time images without much loss in resolution;

examination playback stored in the memory (loop playback);

regulation of the beam focus sites;

measurement software;

ultrasound image storing system.

For contrast enhanced examinations, the ultrasound equipment must meet the following requirements: electronic broadband or multi-frequency transducers, the software to conduct examinations with low or high mechanical indices, complete Doppler options and the possibility to measure time

Preparation for examination

In order to obtain optimal conditions to assess the spleen, it is recommended to perform ultrasound on an empty stomach. The patient should not eat for 6-8 hours and drink for 2 hours before the examination(3).

Examination technique

Due to the anatomical position of the spleen, it is best accessible when the patients assume supine position and next, right lateral position with their left arm placed behind the head, which broadens the intercostal space. The examination may be supplemented with an assessment made in the sitting or standing positions, which in some cases, it is the best method of spleen imaging. The transducer should be applied obliquely along the 9th or 10th intercostal space in the anterior axillary, midaxillary or sometimes, in the posterior axillary lines(3). By a swinging movement of the transducer, longitudinal sections of the spleen are obtained. The most optimal scan is the one which presents the whole spleen from the superior to the inferior pole as well as its hilum and splenic vessels(4). These projections also show the costodiaphragmatic recess, left subdiaphragmatic area, recess between the spleen and left kidney and the tail of the pancreas. The assessment of the spleen in transverse and oblique sections constitute a supplementation of the longitudinal one(3). The patient should breathe easily during the examination since after deep inhalation, the superior pole of the spleen becomes covered by the lowering lung(4).

Evaluation of the shape, echogenicity and size of the spleen

In the longitudinal section, the spleen takes the shape of a crescent but the proportion of its length to its width may differ. In some patients, the spleen is narrow and long whereas in others, it is wide and short(4). Moreover, anatomical variants also affect its shape. Such variants include: accessory spleens, prominent poles and persistent fetal lobulation(5). If the spleen is not visible in its typical localization, it should be searched for in an ectopic position: to the back towards the left kidney or in the pelvis minor. Wandering spleen is anchored on a long vascular pedicle which enables its movement and entails the risk of torsion with subsequent splenic infarction(6).

The echogenicity of the normal spleen is usually higher than that of the liver. However, in some patients, it may be normo- or hypoechoic in relation to the liver(6). The echostructure of this organ is homogenous and fine-grained. Diffuse or focal loss of echogenicity may accompany the pathologies of the reticuloendothelial system and increased echogenicity of the parenchyma is observed in some patients suffering from storage diseases.

The dimensions of the normal spleen should no exceed the following values: 120 mm in length, 70 mm in width and 40 mm in thickness(4). Frequently, the length of the spleen is considered a single, sufficient and adequate factor determining its size, which is helpful in monitoring the course of various diseases(7). In the case of substantial splenomegaly, reaching the left wing of the ilium, the precise measurement of the spleen size is frequently problematic. In such situations, one may sum up the images in the same sections, measure the fragment which is not covered by the left costal margin or in the examination description, provide the approximate localization of the inferior pole.

Evaluation of the splenic hilum

In the splenic hilum, one may see the splenic artery and slightly wider splenic vein whose diameter should not exceed 10 mm in normal conditions(4). The vessels of the collateral circulation occurring in portal hypertension may also be noticed as slight, round or tortuous hypoechoic structures with anastomoses that are clearly visible in a Doppler examination. Doppler ultrasound scan enables to differentiate between the collateral vessels and lymph nodes (figs. 1, 2). In the splenic hilum, the following structures may be visualized: tumor of the tail of the pancreas, tumor of the splenic flexure of the colon as well as neoplasm arising from the kidney and the lateral limb of the left adrenal gland.

Fig. 1.

Enlarged lymph nodes in a patient with lymphoma (arrows)

Fig. 2.

Collateral vessels in the splenic hilum (arrows)

In 0.1–11% of the examined population, an anatomical variant is detected in the hilum, i.e. accessory spleen. It is usually a single change with the size of 10–40 mm and the echogenicity identical to that of the splenic parenchyma. In most cases, it is located at one third of the lower length of the hilum or sometimes, in the area of the poles(5) (fig. 3). The accessory spleen may become enlarged in the course of all the diseases which result in splenomegaly. Additionally, it may hypertrophy after splenectomy(7).

Fig. 3.

Three accessory spleens (arrows)

Pathologies of the spleen

Splenomegaly

The enlargement of the spleen (splenomegaly) is the most common splenic pathology. It is a non-specific symptom and may occur in:

generalized or local inflammation;

hematological and proliferative diseases;

vascular changes (hepatic cirrhosis, portal hypertension, thrombosis of the portal and splenic veins, Budd-Chiari syndrome, obstruction of the inferior vena cava, rightsided cardiac failure and constrictive pericarditis);

storage diseases (Gaucher disease, Hunter syndrome and Niemann-Pick disease);

Wegener's granulomatosis, amyloidosis and sarcoidosis;

immune system disorders (lupus erythematosus, AIDS and Felty's syndrome);

idiopathic splenomegaly.

Storage diseases

These are a group of inherited disorders caused by the lack of the activity of one of the enzymes. Consequently, the substances accumulate in lysosomes and do not undergo degradation but are deposited in body tissues(8, 9). As a consequence of the affected liver and spleen, cirrhosis and hypersplenism may occur. The spleen is enlarged to various degrees, its echogenicity remains normal or the areas of fibrosis and infarction may occur. The most common storage diseases include Gaucher disease, Hunter syndrome and Niemann-Pick disease.

Focal lesions

More than a half of all splenic focal lesions are benign (the most common are infarctions and cysts). In the remaining cases, malignant lesions, such as lymphoma, are diagnosed. As far as echogenicity is concerned, the lesions are divided into cystic and solid, including hypo- and hyperechoic ones (tab. 1). In order to facilitate the differentiation of the character of lesions, a contrast-enhanced ultrasound examination might be conducted.

Tab. 1.

Division of focal lesions of the spleen in terms of their echogenicity

| Cystic lesions | Hypoechoic lesions | Lesions of mixed or increased echogenicity |

|---|---|---|

| Primary cysts Secondary cysts Parasitic cysts Hematoma Abscess Metastases Pseudoaneurysm Lymphangioma Splenoma Infarction |

Lymphomas Metastases Infarction Abscess Microabscesses Mycotic abscesses Tuberculosis Histoplasmosis Amyloidosis Sarcoidosis Immune system diseases |

Hemangioma Splenoma Angiosarcoma Tuberculosis Histoplasmosis Toxocarosis Pneumocystosis Schistosomiasis Abscess |

Benign focal lesions

In the CEUS examination, benign lesions present the same level of perfusion as the parenchyma. Thus, they are isointense in comparison to the surrounding parenchyma with long-lasting enhancement in the delayed phase(10, 11). Sometimes, however, the patterns of enhancement of benign and malignant lesions may overlap as in angiomas which show contrast wash-out in an identical way to malignant lesions(1).

Infarction

It is one of the most common benign lesions of the spleen. It is caused by a thrombus in the branch of the splenic artery and appears in the course of various hematological diseases (lymphomas, leukemias, myelofibrosis, hypercoaguability, polycythemia or sickle-cell anemia), cardiovascular conditions (endocarditis, atrial fibrillation, artificial valves, vascular prostheses or left atrial thrombosis), traumas, pancreatitis and pancreatic neoplasms, generalized septic conditions as well as immune system disorders(5). The possibility of infarction needs to be taken into account in patients reporting sudden pleural pain in the left hypochondriac region as well as temperature, chills, nausea and vomiting. In the US image, infarction takes the form of a pyramid turned upside down towards the capsule of the spleen (fig. 4). The echogenicity changes depending on the infarction phase. At first, it is hypoechoic, or sometimes, anechoic. Next, the echogenicity increases. Contrary to adjacent healthy tissue, the infarction area is characterized by the lack of flow in Doppler examination(7). This is a valuable factor which enables to distinguish infarcts of uncharacteristic shape and echogenicity from other focal lesions during CEUS examination in which the infarction area remains hypointense in all phases in relation to the surrounding parenchyma(2). The most common remote consequence of infarction is the formation of pseudocysts, abscesses or calcifications in the splenic parenchyma.

Fig. 4.

Splenic infarction of a characteristic pyramid-like shape (Z)

Cyst

Primary (congenital) cysts are lined with epithelium or endothelium and rarely occur in the spleen. Secondary cysts (pseudocysts) are more common. They usually occur as a result of traumatic changes, post-inflammatory lesions and infarction. Parasitic hydatid cysts, on the other hand, usually develop in the liver (60%), brain or lungs and, more seldom, in the spleen. They are characterized by thick walls, septations and the presence sister cysts inside the lumen. Nonetheless, congenital and acquired cysts may present similar features. If the diameters of primary or secondary cysts exceed 50 mm, the risk of rupturing or bleeding into the lumen is increased (fig. 5). Such complications are usually accompanied by severe pain in the left hypochondriac region. Large cysts constitute an indication for a surgical intervention with the preservation of the healthy splenic parenchyma to the extent possible(5).

Fig. 5.

Congenital cyst with extravasated blood. The cholesterol crystals cause high echogenicity of the lumen

Angioma

Angiomas constitute nearly 10% of benign lesions of the spleen. Histologically, they may be divided into hemangiomas and lymphangiomas. The latter, however, are very rare. In US examinations, they are visualized as wellcircumscribed and usually hyperechoic lesions (fig. 6) but their echogenicity may as well be low of mixed. Their signal becomes enhanced in CEUS examinations in the arterial phase. In the subsequent phases, they remain hypointense in relation to the surrounding parenchyma(11). The solidcystic forms usually concern lymphangiomas which in Doppler examinations show peripheral vascularity. As a result of the blood deposited in large angiomas, coagulopathy, anemia or thrombocytopenia (Kasabach-Merritt syndrome) may occur.

Fig. 6.

Splenic angioma (crosses)

Calcifications

They are usually outcomes of cysts, abscesses, infarction foci or trauma/hematoma(7). They may form in the wall of vessels, cysts and neoplastic lesions. Single calcifications of little clinical significance are the most common. Numerous ones however, raise suspicions of infections such as HIV viral infection, tuberculosis, pneumocystosis, mycosis (candidosis or aspergillosis). They frequently accompany various metabolic disorders(5).

Abscesses

Abscesses of the spleen result from infections spreading by the blood (usually in generalized septic conditions), by contiguity (inflammatory processes of organs such as pancreas, kidney or splenic flexure of the colon) or they are a consequence of splenic infarction or trauma(5). Depending on the factors responsible for infection, there are bacterial and mycotic abscesses. They may reach various sizes and be multiple or single in the form of uni- , bi-, or multilocular lesions.

Bacterial abscesses usually have a well-developed and vascularized capsule (so called pseudocapsule). They are round or oval. Their lumina may be anechoic, hypoechoic, of mixed echogenicity or hyperechoic(5). The presence of reflections inside the lesion, which are typical of gas with incomplete, i.e. dirty, shadowing or the comet-tail artifact attest to anaerobic bacterial infection.

In the case of tuberculous infections especially in the miliary form, the spleen is affected in about 80–100%. In such a situation, slight hyperechoic areas are visible in the entire splenic parenchyma and diffuse calcifications may constitute their outcome (fig. 7). In the case of tuberculosis, it is necessary to assess the liver, lymph nodes and peritoneal cavity in search for the free fluid.

Fig. 7.

Hyperechoic lesions of the spleen – the outcome of the tuberculous process

The diagnostics of fungal microabscesses may cause certain difficulties. They constitute 25% of all splenic abscesses. In the US image they present themselves as slight (2–4 mm) hypoechoic areas scattered in the entire organ. First and foremost, microabscesses are found in immunocompromised patients (with AIDS, the history of chemotherapy or organ transplant)(5).

Mature mycotic abscesses, which are usually caused by Candida and Aspergillus, may present various ultrasound images. Their most characteristic feature is the “wheelwithin-a-wheel” pattern (hypoechoic center made of necrotic cells surrounded by hyperechoic layer of inflamed cells). The remaining variants, such as a “target” pattern (alternating concentric hypo- and hyperechoic rims), hypoor hyperechoic lesions are non-specific (fig. 8). In the differential diagnostics of abscesses, it is very important to combine US findings with clinical data and results of laboratory tests. In the case of doubts, it is recommended to verify the findings by performing ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy or contrast-enhanced examinations. The inside of the abscess, which is filled with fluid or necrosis, is hypointense in relation to the normal splenic parenchyma and in the delayed phase, one may solely observe the enhancement of the septations and pseudocapsule(1, 2).

Fig. 8.

Mycotic abscess of the spleen – the appearance of the “target”

Splenoma

It is a benign tumor formed from a “mixture” of splenic tissues (vascular channels of various width which are lined with endothelium without the features of atypia and stroma, similar to the red splenic pulp with or without lymphatic nodules)(12). It usually occurs as a solitary formation. Its multiple form may be observed in the course of tuberous sclerosis and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. In US examinations, the lesion is well-circumscribed, homogeneous or non-homogeneous and includes cysts, calcifications or areas of necrosis. Sometimes, its echogenicity is decreased or mixed (fig. 9). In CEUS examinations in the early phase, choristomas present enhancement which is homogeneous and isointense in relation to the splenic parenchyma. The enhancement slightly increases in the parenchymal phase(11).

Fig. 9.

Splenoma (arrow)

Malignant focal lesions

The most common malignant lesions in the spleen include: generalized lymphoma, leukemic infiltrations and angiosarcoma. In CEUS examinations, the enhancement in the early phase with subsequent quick contrast wash-out is characteristic of lymphomas and metastases(1, 2, 11).

Primary malignant neoplasms

Primary malignant neoplasms of the spleen occur seldom.

Angiosarcoma is usually a solitary, well-circumscribed, hypo- or normoechoic tumour with high growth potential. It quickly metastasises to the lymph nodes and liver. It is detected in patients exposed to asbestos or polyvinyl chloride.

Primary splenic lymphoma constitutes about 1% of all lymphomas(5). Similarly to the secondary involvement of the lymphatic system and irrespective of the form of the lesion (uni- or multilocular), it usually presents low echogenicity, which very rarely is higher that the echogenicity of the healthy spleen.

Metastases to the spleen

Secondary involvement of the spleen or other structures of the lymphatic system by malignant neoplasms constitutes the evidence of the generalization of the disease(4). In US examinations, such lesions are more frequently diagnosed in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphomas than in those with Hodgkin's disease. This happens because non-Hodgkin lymphomas much more often affect the organs in the abdominal cavity, including the spleen, liver and retroperitoneal lymph nodes(5).

In the case of non-Hodgkin lymphomas at the early stage, the liver and spleen are involved in 30% of patients and in further stages – in 60% of patients. In Hodgkin lymphoma, however, the spleen becomes affected in 30% of patients only in the advanced stages. The abdominal form of the disease more often affects the lymph nodes and liver than the spleen. US images are diversified both in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The spleen may become slightly or moderately enlarged and the echogenicity of the parenchyma may remain normal. Some patients present diffuse or focal areas of decreased echogenicity or cyst-like areas which may be single or multiple (figs. 10, 11).

Fig. 10.

Single lymphoma in the form of a solid-cystic focal lesion

Fig. 11.

Splenic parenchyma infiltrated by lymphoma

In the course of leukemias, the spleen undergoes enlargement, which is rarely accompanied by the change of echogenicity. Furthermore, as in the case of lymphomas, abdominal lymphadenopathy is observed(7).

The metastases to the spleen occur in 7.5% of patients suffering from malignant neoplasms. Out of epithelial neoplasms, metastases to the spleen come from carcinomas of: the ovary, mammary gland, colon, uterine body and cervix, prostate gland, stomach, pancreas, esophagus and thyroid gland. Out of non-epithelial neoplasms, however, most of the metastases come from cutaneous melanoma(13, 14) (fig. 12 A, B). Similarly to the liver, the image of the metastases in the spleen is diversified even in the case of one malignant neoplasm. On the other hand, several malignancies may present similar US images. Therefore, the origin of the neoplasm cannot be determined on the basis of US examinations.

Fig. 12 A.

Metastases of the melanoma to the spleen – the appearance of the “target” (arrow)

Fig. 12 B.

Metastasis of the melanoma to the spleen as a solitary cyst-like focal lesion (arrow)

Most of the tumors present decreased echogenicity (it is more rarely increased). They may be cystic-solid and include the areas of necrosis as well as calcifications or show the “bull's eye” pattern (i.e. hyperechoic center and hypoechoic rim). Isolated metastases to the spleen usually come from ovarian carcinoma as well as melanoma and constitute an indication for surgical intervention. Rarely are metastases to the spleen the first symptom of a neoplastic disease. If there is no primary focus, ultrasound enables to verify the metastases by means of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy.

Vascular changes

Splenic vein thrombosis usually accompanies portal vein thrombosis and presents identical etiology (usually pancreatitis or a clot of neoplastic origin). Thrombosis results in splenomegaly and collateral circulation. In the B-mode examination, the enlargement of the spleen is a specific symptom. Doppler examination, however, confirms the lack of flow in the splenic vein as well as the presence of collateral vessels and the clot in the lumen of the splenic vein, whose width exceeds 10 mm(7).

Aneurysms of the splenic artery are uncommon. They become clinically significant when the diameter exceeds 20 mm, which raises the risk of rupturing and hemorrhage. They usually appear in connection with portal hypertension or during pregnancy. In US examinations, they present themselves as cystic lesions in the splenic hilum. They show the evidence of arterial flow in color and spectral Doppler examinations(7) (fig. 13 A, B).

Fig. 13 A.

Aneurysm of the splenic artery (arrow)

Fig. 13 B.

Aneurysm of the splenic artery

False aneurysm of the splenic artery is a very rare complication of usually acute (and more seldom, chronic) pancreatitis and abdominal trauma(15). Sometimes, it appears as a result of splenic infarction or neoplastic infiltration(7). In B-mode examinations, pseudoaneurysms are frequently mistaken for cysts or fluid reservoir around the pancreas after its inflammation. For accurate diagnosis, Doppler examination or angio-CT are necessary(15).

Splenic traumas

The spleen is especially susceptible to direct injuries as a result of trauma to the left hypochondriac region or 9th–11th ribs as well as to indirect blunt injuries such as a fall from height or traffic accident. Clinical injuries of the spleen are divided into the single-stage lesions, resulting in an immediate rupture with instant hemorrhage into the peritoneal cavity, and two-stage lesions resulting in a delayed rupture. In the latter, a subcapsular hematoma occurs which may either rupture into the peritoneal cavity or absorb after various periods of time(16).

Generally applicable US criteria concerning splenic traumas (so called Asher criteria) include the following features of the injury: enlargement, irregular contour of the capsule, alteration of the contours with the change of the patient's position, double contour sign and the presence of free fluid in the peritoneal cavity(17). In unstable patients, a US examination is conducted according to a standardized procedure called FAST (Focused Assessment Sonography for Trauma). Stable patients, who are not in a life-threatening condition, undergo US examinations according to the standards of the Polish Ultrasound Society(3).

The most severe splenic trauma, which is an indication for emergency surgery, comprises rupture of the splenic capsule with the laceration of the parenchyma and intraperitoneal hemorrhage(18). The US image presents hypoechoic, irregular area of the hematoma between the divided parenchymal fragments. Some fluid appears around the spleen as well as in other areas of the abdomen. The intraperitoneal blood resorbs within 2–4 weeks. However, several months to a year are needed for the blood within the spleen to absorb. The outcomes of hematoma may include its complete resorption, formation of pseudocyst or, more rarely, superinfection with the formation of an abscess (4).

Splenic rupture without the laceration of the parenchyma is undetectable in US examinations. The only sign of such a condition may be the presence of the fluid in the peritoneal cavity(4).

Splenic trauma may also result in subcapsular and intraparenchymal hematomas with preserved integrity of the capsule (figs. 14, 15). Although in such cases, clinical symptoms are minimal, patients require to be monitored due to the risk of delayed splenic rupture(4).

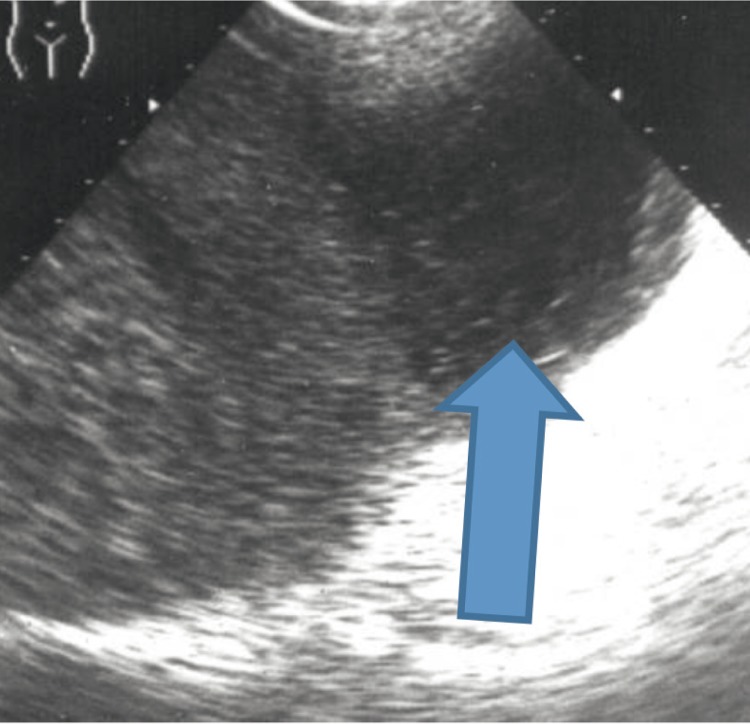

Fig. 14.

Subcapsular hematoma of the spleen (arrow)

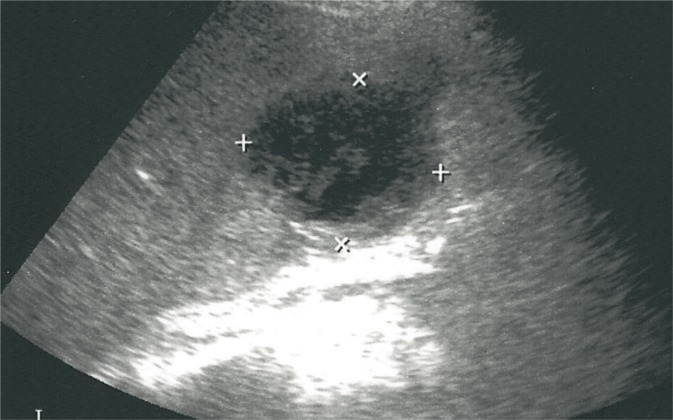

Fig. 15.

Splenic hematoma (crosses)

Initially, intraparenchymal hematoma/parenchymal contusion is an isoechoic area which is difficult to distinguish from normal parenchyma. Later, however, the contusion area becomes heterogeneous and, finally, hypoechoic with scattered tissue elements(4).

Subcapsular hematomas are most frequently localized at the convex area of the spleen and are crescent-shaped. Their echogenicity may vary and depends on their formation period. In the acute phase, as a result of fibrin creation, the echogenicity of the hematoma is increased. In later periods, the echogenicity decreases until anechoic areas are formed(18).

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage or formation of subcapsular hematoma may be initially manifested by the enlargement of the spleen to various degrees.

Spontaneous splenic ruptures occur seldom, usually in the diseases manifested by splenomegaly(4).

Examination description

The examination description should include the patient's personal details, date of examination, name of the facility in which the examination was performed, name of the scanner as well as the type of the transducer and its frequency. Next, the size (length and width in mm), contours and echogenicity of the spleen should be described as well as possible anatomical variants, all abnormal morphological changes and (if possible) their number, size, echogenicity, echostructure (solid or cystic), localization and, finally, vascularity. Moreover, the splenic hilum should be thoroughly checked for the presence of the collateral vessels or enlarged lymph nodes. The examination description should be ended with specific conclusions as well as suggestions for further diagnostic algorithm and check-up examinations(3). In the case of detecting abnormal morphological changes, the photographic documentation should be attached to the description with the specification of the number of the photographs. Finally, the finding description should be stamped and singed by the examiner.

Conclusion

Ultrasound examination constitutes the primary diagnostic method to diagnose and differentiate between pathological changes in the spleen. The examination performed according to the standards of the Polish Ultrasound Society will allow for an optimal assessment of this organ and accurate interpretation of detected changes indicating (in appropriate cases) a therapeutic method or further diagnostic examinations.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not report any financial or personal links with other persons or organizations, which might affect negatively the content of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication

References

- 1.Piscaglia F, Nolsøe C, Dietrich CF, Cosgrove DO, Gilja OH, Bachmann Nielsen M, et al. The EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Practice of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS): update 2011 on non-hepatic applications. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33:33–59. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popescu A, Sporea I, Şirli R, Dănilă M, Nicoliţă D, Martie A. The role of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with second generation contrast agents in the evaluation of focal splenic lesions. Med Ultrason. 2009;11:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jakubowski W, editor. Praktyczna Ultrasonografia. 4. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2011. Standardy badań ultrasonograficznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego; pp. 158–160. 355–357. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jakubowski W, editor. Praktyczna Ultrasonografia. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2003. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna w gabinecie lekarza rodzinnego; pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakubowski W, editor. Praktyczna Ultrasonografia. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2005. Błędy i pomyłki w diagnostyce ultrasonograficznej; pp. 124–137. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates JA. Ultrasonografia jamy brzusznej. In: Jakubowski W, editor. 2. Wrocław: Elsevier Urban & Partner; 2012. p. 175. red. wyd. pol. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates JA. Ultrasonografia jamy brzusznej. In: Jakubowski W, editor. 1. Wrocław: Elsevier Urban & Partner; 2006. pp. 135–148. red. wyd. pol. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubicka K, Kawalec W, editors. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL; 2010. Pediatria. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobrzańska A, Ryżko J, editors. Podręcznik do Państwowego Egzaminu Lekarskiego i egzaminu specjalizacyjnego. Wrocław: Urban & Partner; 2005. Pediatria. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu X, Yu J, Liang P, Liu F. Real-time contrast-enhanced ultrasound in diagnosing of focal spleen lesions. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Herbay A, Barreiros AP, Ignee A, Westendorff J, Gregor M, Galle PR, et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography with SonoVue: differentiation between benign and malignant lesions of the spleen. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:421–434. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.4.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H, Maeda K. Hamartoma of the spleen. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:147–151. doi: 10.5858/133.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Compérat E, Bardier-Dupas A, Camparo P, Capron F, Charlotte F. Splenic metastases: clinicopathologic presentation, differential diagnosis, and pathogenesis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:965–969. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-965-SMCPDD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadasik D, Kostecki J, Zaniewski M. Guzy przerzutowe do śledziony – przegląd literatury. Chirurgia Polska. 2008;10:175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wroński K, Dziki Ł, Cywiński J, Pakuła D, Bocian R, Dziki A. Chirurgiczne leczenie tętniaka rzekomego tętnicy śledzionowej po ostrym zapaleniu trzustki – opis dwóch przypadków i przegląd literatury. Ostry Dyżur. 2010;3:68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Góral R, editor. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL; 1992. Zarys chirurgii; p. 673. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakubowski W, editor. Praktyczna Ultrasonografia. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2004. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna w ostrych chorobach jamy brzusznej; pp. 180–189. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer H, Dobrinski W, editors. 1. Wrocław: Urban & Partner; 1996. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna; pp. 159–169. [Google Scholar]