Abstract

Pemphigus is a group of immune-mediated bullous disorders, which often cause fragile blisters and extensive lesions of the skin or mucous membranes, such as in the mouth. This disease could be life-threatening in some cases. During pregnancy, its condition will become more complicated due to the change in the mother’s hormone level and the effect of drug therapy on both the mother and her fetus. Thus, it will be more difficult to identify the clinical manifestations and to establish the treatment plan. In this article, we present a comprehensive review of pemphigus and pregnancy by analyzing 47 cases of pemphigus reported between 1966 and 2014, with diagnosis before or during pregnancy. The aim of this study is to make a comprehensive review of pemphigus and pregnancy, provide organized and reliable information for obstetricians, dermatologists, physicians, and oral medicine specialists.

Pemphigus is characterized by widely distributed bullae and erosions on the skin and mucosa membranes. There are mainly 3 types of pemphigus: Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), Pemphigus foliaceus (PF), and other variants of pemphigus.1,2 The pathogenesis of pemphigus is associated with autoantibodies directed against transmembrane glycoproteins of desmosomes, which causes steric hindrance to homophilic adhesion of desmogleins, and results in the formation of Dsg1-depleted desmosomes in PF and Dsg3-depleted desmosomes in PV.3,4 Pemphigus usually affects the elderly, and genetics play an important role in predisposition.5,6 Pemphigus could involve one or more mucosae, while PV often shows extensive lesions of the oral mucosa.7,8 When it occurs in pregnancy, the condition becomes more complex.9 Early diagnosis and individually adjusted therapy are needed to avoid any risk for mother or child.10 The purpose of this article is to make a comprehensive review of the pemphigus and pregnancy, and provide organized and reliable information for clinicians.

Basic demographics

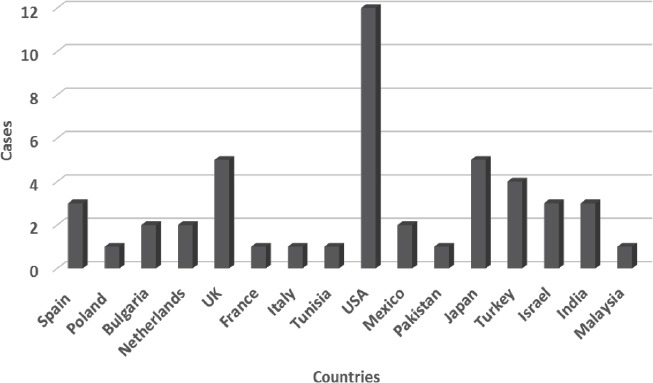

The existing reseasrch is mainly focused on case reports and retrospective studies. References were retrieved by an electronic search strategy “(pemphigus [MeSH Terms]) AND pregnancy [MeSH Terms] Filters: Case Reports” on PubMed, and a total of 62 cases were reviewed. Of the 62 cases, 14 were excluded based on abstract, which indicated discussion about gestational pemphigoid, and 7 were excluded because they were non-English. Finally, we included 41 relevant case reports according to their titles and abstracts. These 41 case reports between 1966 and 2014 involved 47 women identified with pemphigus before (n=21 cases) or during pregnancy (n=26 cases). These cases of pemphigus and pregnancy have been reported in different populations, Asia, Europe, and North America, with more than in Africa, South America, and Oceania (Figure 1). A recent study from the United Kingdom has suggested an incidence of PV of 0.68 cases per 100,000 persons per year. The incidence varies in different areas, being more common in the Near and Middle East than in Western Europe and North America.11-14

Figure 1.

Regional distribution of 47 cases of pemphigus and pregnancy between 1966 and 2014.

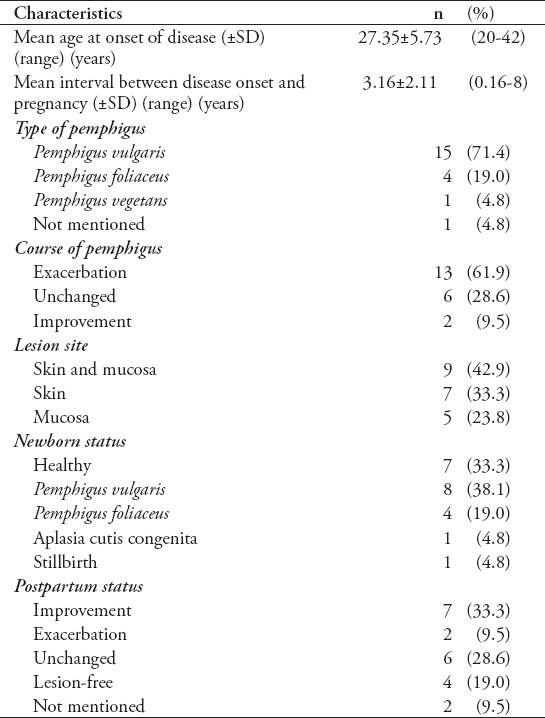

We analyzed the characteristics of 21 patients with pemphigus diagnosed before pregnancy. Among them, 71.4% were diagnosed as PV, 19% as PF, 4.8% as Pemphigus vegetans, while the remaining was indefinite. The age of onset of pemphigus was generally 20-42 years old (mean age 27.35±5.73), with a mean interval of 3.16±2.11 years between disease onset and pregnancy. The pemphigus course was characterized by exacerbation (61.9%), improvement (9.5%), and remaining stable (28.6%) during the pregnancy. The newborn status is meaningful for our conclusion. The incidence of neonatal pemphigus was as high as 57.1% (including 38.1% of PV and 19% of PF). In contrast, the percentage of healthy neonates was only 33.3%, which may be considered to be publication bias (Table 1).15-31

Table 1.

Characteristics of 21 patients with pemphigus diagnosed between 1966 and 2013.

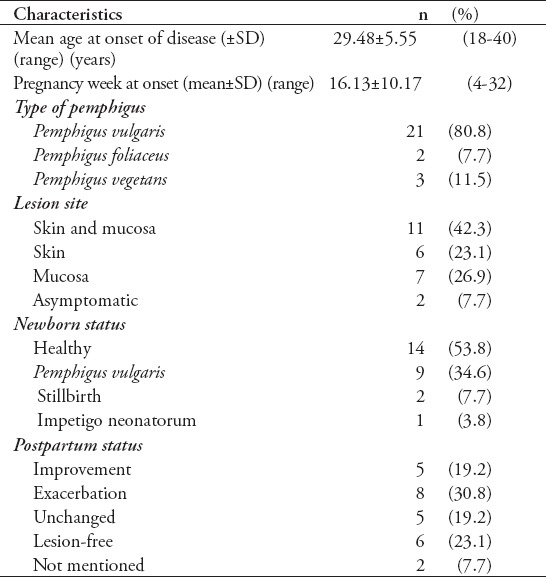

It seems to be quite a rare phenomenon that pregnancy as a triggering factor of PV seems to be quite a rare phenomenon.13 Table 2 summarizes 26 cases with onset of pemphigus during pregnancy between 1996 and 2013. The mean onset of pemphigus was during 16.13±10.17 (4-32) weeks of pregnancy. Among the cases, 2 cases were asymptomatic, while the remaining 24 patients’ lesion sites were on skin (23.1%), mucosa (26.9%), or both of them (42.3%). Most of the patients (53.8%) gave birth to a healthy, full-term neonate. There were 34.6% of neonate PV and 3.8% of impetigo neonatorum. Pregnancy resulted in stillbirth in 2 of 26 cases (7.7%), which is considerable in our series. The postpartum status of the mothers was also unoptimistic. Only 42.3% entered remission (including 19.2% of improvement and 23.1% of lesion-free), while the proportion of exacerbation was high at 30.8%, which is still considerable (Table 2).4,14,19,32-52

Table 2.

Characteristics of 26 patients with pemphigus diagnosed during pregnancy between 1966 and 2013.

Effects on the mother

If a pregnant woman becomes sick (such as pemphigus), she is more likely to suffer from disorders of the neuroendocrine system and immune system due to the state of high pressure.53 According to the current study, the mother’s condition may exacerbate, enter into remission, or remain stable during the pregnancy.54 The disease is aggravated most likely during the first, second trimester, and postpartum, then is relived during the third trimester.15 This may be due to the increased level of endogenous corticosteroid hormone chorion and subsequent immunosuppression.40,55 Although some literature reports the postpartum flare of pemphigus due to the rapid drop of corticosteroid hormones levels, the postpartum status in our study was optimistic, only 2 cases (9.5%) of pemphigus diagnosed before pregnancy and 8 cases (30.8%) of pemphigus diagnosed during pregnancy exacerbated after delivery.19,56 However, some patients with pemphigus during pregnancy may not show any obvious changes, especially those patients in remission.9,15

Effects on the mode of delivery

Goldberg et al32 and Fainaru et al14 indicated that the trauma of vaginal delivery can result in extension and deterioration of the wound. In a cesarean section, patients who receive long-term steroid therapy will increase the risk, and the disease itself, and corticosteroid therapy may complicate wound healing. Therefore, delivery by cesarean section is the absence of additional benefits. Except for obstetric contraindications, vaginal delivery is recommended. Although it is a potential risk that local blisters may result in passive transfer of antibodies to the fetus through the breast milk, breastfeeding is not contraindicated.

Effects on the pregnancy outcome

Pregnancy outcome includes live birth, stillbirth, spontaneous abortion, and induced abortion.57 Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy may result in abortion, fetal growth retardation, intrauterine death, premature delivery, and in approximately 30% neonatal PV of the newborns.58 In this article, we will discuss the 3 most common outcomes of pemphigus in pregnancy: normal fetal outcome, neonatal pemphigus, and stillbirth.

Normal fetal outcome

Most of the patients with pemphigus can give birth to a normal full-term, healthy newborn through vaginal delivery or cesarean section, depending on the collaborative efforts of the dermatologist and obstetrician.56 In our study, although there were only 7 (33.3%) healthy neonates from the cases with pemphigus diagnosis before pregnancy, we considered it likely to be an underestimate due to the less frequent reports of successful deliveries than that of neonatal adverse outcomes.

Neonatal pemphigus

Neonatal pemphigus is a rarely reported transitory autoimmune blistering disease. It is clinically characterized by transient flaccid blisters and erosions on the skin and rarely on the mucous membranes.17 The disease can be self-healing at 2-3 weeks without special treatment, and does not have long-term clinical significance. No new vesicles or bullae appears in the newborn after birth. Neonatal PV has never been reported to persist beyond the neonatal period and progress to adult disease.17,34,35,39 Neonatal pemphigus is mainly due to the transplacental transmission of antibodies, and only a very small amount of immunoglobulin G (IgG) is synthesized by the neonate itself.36,59 Pemphigus IgG is found both in the fetal circulation and fixed to the fetal epidermis in a characteristic intercellular distribution, while IgA, IgM, IgE, and IgD generally do not participate in the passive transport.60 Contrary to PV, PF in pregnant women rarely leads to neonatal skin lesions.61 The absence of skin disease in the newborns may be due to low transfer of IgG4 autoantibodies through the placenta, and the “immunosorbent” effect of the placenta to contain desmosomes and desmogleins.62-65 This is because to the distribution and cross-compensation of the pemphigus antigens desmoglein 3 and 1 in neonatal and adult skin or mucosa are different.60

Stillbirth

In the literature, the rate of stillbirth in pemphigus during pregnancy was reported to range from 1.4-27%.18,33,56,66 In contrast to the high percentage of some previous observations, pregnancy ended in stillbirth in only one case (4.8%) of pemphigus diagnosed before pregnancy and 2 cases (7.7%) of pemphigus diagnosed during pregnancy in our study. The occurrence of stillbirth emphasizes the management problems encountered when a pemphigus patient becomes pregnant.56,66

No relevance has been indicated between maternal treatment regimen and fetal outcome.38,67 Instead of particular medications, adverse pregnancy outcomes seem to be correlated more closely to poor maternal disease control, higher maternal serum, and umbilical cord blood antibody titers.38

Treatment options

Almost all types of pemphigus patients experience severe worsening of the disease after delivery if there is a lack of treatment during pregnancy (n=66). Treatment is often required to control both maternal diseases and fetal outcomes.68 The current study suggested that standard therapy gives priority to systemic glucocorticoids, alone or in combination with other immunosuppressive agents such as immunosuppressant, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) or plasmapheresis.15,32,69 If the disease worsens during the first trimester, a medical termination of pregnancy may be considered, and if it happens during the second and third trimester, application of corticosteroids is a safe treatment.20 The treatment of pemphigus patients diagnosed during pregnancy is similar to the treatment before pregnancy.38

Glucocorticoids

The use of systemic steroids is considered safe in pregnancy, and glucocorticoid remains the first-line agent for treatment with low dosages when patients are mildly ill.70 Some corticosteroids such as prednisone (FDA pregnancy category B), featured with a fast action and high pharmacological effect, can be safely used as immunosuppressive drugs during pregnancy as they do not readily cross the placenta. Prednisone is the safest drug compared with other less used glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone and betamethasone.71,72 The dose of prednisone/prednisolone should be reduced to the lowest effective dose, and standardized doses are still experimental.15,19,32,56

Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppression of steroid-sparing agents are needed when pemphigus has to be controlled by larger doses of medications. Azathioprine is the most widely used steroid-sparing agent for pemphigus.73,74 Cyclosporine is believed to be less effective in the treatment of pemphigus, but it is the safest corticosteroid-sparing agent in pregnancy.38,69 Mycophenolatemofetil, cyclophosphamide, and methotrexate are strongly discouraged or even contraindicated in pregnancy.38,72

Intravenous immunoglobulin

There is moderate evidence suggestive of an effective and safe effect of IVIg as an auxiliary therapy in pregnancy patients with pemphigus.75-77 Therefore, when pregnancy is associated with significant medical problems or disease states, clinicians may need to consider using IVIg early.78

Plasmapheresis

Plasmapheresis is a useful alternative immunosuppressive therapy in pregnancy, which can be used as adjuvant therapy, combined with systemic corticosteroids, reducing the dosage of glucocorticoid treatment.21

In conclusion, the patients may suffer from pemphigus before or during pregnancy. The condition of pemphigus and pregnancy can interact with each other and make the treatment and prognosis of these diseases more complicated, presenting challenges for the clinician. Pregnancy may precipitate or aggravate pemphigus, and new born babies of such patients may have a normal outcome or neonatal pemphigus, or, rarely, a stillbirth. Current treatment of pemphigus coexisting with pregnancy priorities systemic glucocorticoids, alone or in combination with other immunosuppressive agents such as immunosuppressants, IVIg or plasmapheresis. The number of reported cases of pemphigus in pregnancy is too small to predict the change of conditions for an individual patient. In summary, pemphigus and pregnancy is still an indistinct area that needs collaborative work by obstetricians, dermatologists, neonatologists, endocrinologists, and oral medicine specialists, to establish a mechanism of multi-disciplinary treatment.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Kitajima Y, Aoyama Y. A perspective of pemphigus from bedside and laboratory-bench. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2007;33:57–66. doi: 10.1007/s12016-007-0036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruocco E, Wolf R, Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Romano F, Lo Schiavo A. Pemphigus: associations and management guidelines: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:382–390. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joly P, Gilbert D, Thomine E, Zitouni M, Ghohestani R, Delpech A, et al. Identification of a new antibody population directed against a desmosomal plaque antigen in Pemphigus and Pemphigus foliaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;108:469–475. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12289720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hertl M, Niedermeier A, Borradori L. Autoimmune bullous skin disorders. Ther Umsch. 2010;67:465–482. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930/a000080. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firooz A, Mazhar A, Ahmed AR. Prevalence of autoimmune diseases in the family members of patients with Pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(3 Pt 1):434–437. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker BA, Gaspari AA. Pemphigus vulgaris and vegetans. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:429–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott JE, Ahmed AR. The blistering diseases. Med Clin North Am. 1998;82:1239–1283. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70415-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kneisel A, Hertl M. Autoimmune bullous skin diseases. Part 1: Clinical manifestations. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:844–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07793.x. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torgerson RR, Marnach ML, Bruce AJ, Rogers RS., 3rd Oral and vulvar changes in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renner R, Sticherling M. Chronic inflammatory and autoimmune mediated dermatoses during pregnancy. Course and prognosis for mother and child. Hautarzt. 2010;61:1021–1026. doi: 10.1007/s00105-010-2007-7. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langan SM, Smeeth L, Hubbard R, Fleming KM, Smith CJ, West J. Bullous pemphigoid and Pemphigus vulgaris. Incidence and mortality in the UK: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a180. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon DG, Krutchkoff D, Kaslow RA, Zarbo R. Pemphigus in Hartford County, Connecticut, from 1972 to 1977. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1035–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bialynicki-Birula R, Dmochowski M, Maj J, Gornowicz-Porowska J. Pregnancy-triggered maternal pemphigus vulgaris with persistent gingival lesions. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2011;19:170–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fainaru O, Mashiach R, Kupferminc M, Shenhav M, Pauzner D, Lessing JB. Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: a case report and review of literature. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1195–1197. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.5.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalayciyan A, Engin B, Serdaroglu S, Mat C, Aydemir EH, Kotogyan A. A retrospective analysis of patients with pemphigus vulgaris associated with pregnancy. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:396–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.48299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terpstra H, de Jong MC, Klokke AH. In vivo bound pemphigus antibodies in a stillborn infant. Passive intrauterine transfer of pemphigus vulgaris? Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:396–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campo-Voegeli A, Muñiz F, Mascaró JM, García F, Casals M, Arimany JL, et al. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris with extensive mucocutaneous lesions from a mother with oral pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:801–805. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storer JS, Galen WK, Nesbitt LT, Jr, DeLeo VA. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982;6:929–932. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)80127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruach M, Ohel G, Rahav D, Samueloff A. Pemphigus vulgaris and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1995;50:755–760. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199510000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanwar AJ, Thami GP. Pemphigus vulgaris and pregnancy--a reappraisal. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;39:372–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1999.tb03421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shieh S, Fang YV, Becker JL, Holm A, Beutner EH, Helm TN. Pemphigus, pregnancy, and plasmapheresis. Cutis. 2004;73:327–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Jornet P, Bermejo-Fenoll A. Gingival lesions as a first symptom of pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy. Br Dent J. 2005;199:91–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonifazi E, Milioto M, Trashlieva V, Ferrante MR, Mazzotta F, Coviello C. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris passively transmitted from a clinically asymptomatic mother. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 Suppl):S113–S114. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muhammad JK, Lewis MA, Crean SJ. Oral pemphigus vulgaris occurring during pregnancy. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:121–124. doi: 10.1046/j.0904-2512.2001.00000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hern S, Vaughan Jones SA, Setterfield J, Du Peloux Menag H, Greaves MW, Rowlatt R, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy with favourable foetal prognosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:260–263. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.1998.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bialynicki-Birula R, Dmochowski M, Maj J, Gornowicz-Porowska J. Pregnancy-triggered maternal Pemphigus vulgaris with persistent gingival lesions. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2011;19:170–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okubo S, Sato-Matsumura KC, Abe R, Aoyagi S, Akiyama M, Yokota K, Shimizu H. The use of ELISA to detect desmoglein antibodies in a pregnant woman and fetus. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1217–1218. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.9.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galarza C1, Gutiérrez EL, Ramos W, Tello M, Ronceros G, Alvizuri S, et al. Endemic Pemphigus foliaceus in a pregnant woman. Report of one case. Rev Med Chil. 2009;137:1205–1208. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moncada B, Kettelsen S, Hernandez-Moctezuma JL, Ramirez F. Neonatal Pemphigus vulgaris: role of passively transferred pemphigus antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:465–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb04542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaufman AJ, Ahmed AR, Kaplan RP. Pemphigus, myasthenia gravis, and pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(2 Pt 2):414–418. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergman R, Sujov P, Peled M, Diaz L, Etzioni A. Primary persistent autoimmune disorder in a neonate. Lancet. 1999;353:124. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)76161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg NS, DeFeo C, Kirshenbaum N. Pemphigus vulgaris and pregnancy: risk factors and recommendations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(5 Pt 2):877–879. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70123-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okano M, Takijiri C, Aoki T, Wada Y, Hayashi A, Fuke Y, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris associated with pregnancy. A case report from Japan. Acta Derm Venereol. 1990;70:517–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merlob P, Metzker A, Hazaz B, Rogovin H, Reisner SH. Neonatal Pemphigus vulgaris. Pediatrics. 1986;78:1102–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chowdhury MM, Natarajan S. Neonatal Pemphigus vulgaris associated with mild oral Pemphigus vulgaris in the mother during pregnancy. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:500–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hup JM, Bruinsma RA, Boersma ER, de Jong MC. Neonatal Pemphigus vulgaris: transplacental transmission of antibodies. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:468–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piontek JO, Borberg H, Sollberg S, Krieg T, Hunzelmann N. Severe exacerbation of Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: successful treatment with plasma exchange. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:455–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lehman JS, Mueller KK, Schraith DF. Do safe and effective treatment options exist for patients with active Pemphigus vulgaris who plan conception and pregnancy? Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:783–785. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wasserstrum N, Laros RK., Jr Transplacental transmission of pemphigus. JAMA. 1983;249:1480–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gushi M, Yamamoto Y, Mine Y, Awazawa R, Nonaka K, Taira K, et al. Neonatal Pemphigus vulgaris. The Journal of Dermatology. 2008;35:529–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2008.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iftikhar N, Ejaz A, Butt UA, Ali S. Aplasia cutis congenita associated with azathioprine. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:782–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eyre RW, Stanley JR. Maternal Pemphigus foliaceus with cell surface antibody bound in neonatal epidermis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:25–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirsch R, Anderson J, Weinberg JM, Burnstein P, Echt A, Fermin J, et al. Neonatal Pemphigus foliaceus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 Suppl):S187–S189. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lorente LAI, Bernabeu-Wittel J, Dominguez-Cruz J, Conejo-Mir J. Neonatal Pemphigus foliaceus. J Pediatr. 2012;161:768. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker DC, Kolar KA, Hebert AA, Jordon RE. Neonatal Pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1308–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parlowsky T, Welzel J, Amagai M, Zillikens D, Wygold T. Neonatal Pemphigus vulgaris: IgG4 autoantibodies to desmoglein 3 induce skin blisters in newborns. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:623–625. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fenniche S, Benmously R, Marrak H, Dhaoui A, Ammar FB, Mokhtar I. Neonatal Pemphigus vulgaris in an infant born to a mother with Pemphigus vulgaris in remission. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:124–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daniel Y, Shenhav M, Botchan A, Peyser MR, Lessing JB. Pregnancy associated with pemphigus. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102:667–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb11410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abouleish EI, Elias MA, Lopez M, Hebert AA. Spinal anesthesia for cesarean section in a case of Pemphigus foliaceus. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:449–450. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199702000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Avalos-Díaz E, Olague-Marchan M, López-Swiderski A, Herrera-Esparza R, Díaz LA. Transplacental passage of maternal Pemphigus foliaceus autoantibodies induces neonatal pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:1130–1134. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.110400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ugajin T, Yahara H, Moriyama Y, Sato T, Nishioka K, Yokozeki H. Two siblings with neonatal Pemphigus vulgaris associated with mild maternal disease. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:192–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Driscoll AM. Urinary oestriol excretion in pregnant patient given large doses of prednisone. Br Med J. 1969;1:556–557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5643.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parker VJ, Douglas AJ. Stress in early pregnancy: maternal neuro-endocrine-immune responses and effects. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;85:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmutz JL. Dermatological diseases influenced by pregnancy. Presse Med. 2003;32:1809–1812. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaplan RP, Callen JP. Pemphigus associated diseases and induced pemphigus. Clin Dermatol. 1983;1:42–71. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(83)90022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kardos M, Levine D, Gurcan HM, Ahmed RA. Pemphigus vulgaris in pregnancy: analysis of current data on the management and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64:739–749. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181bea089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shahir AK, Briggs N, Katsoulis J, Levidiotis V. An observational outcomes study from 1966-2008, examining pregnancy and neonatal outcomes from dialysed women using data from the ANZDATA Registry. Nephrology (Carlton) 2013;18:276–284. doi: 10.1111/nep.12044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meurer M. Pemphigus diseases in children and adolescents. Hautarzt. 2009;60:208–216. doi: 10.1007/s00105-009-1733-1. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bjarnason B, Flosadottir E. Childhood, neonatal, and stillborn Pemphigus vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:680–688. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hilario-Vargas J, Vitorio IB, Stamey C, Culton DA, Prisayanh P, Rivitti EA, et al. Analysis of Anti-desmoglein 1 Autoantibodies in 68 Healthy Mother/Neonate Pairs from a Highly Endemic Region of Fogo Selvagem in Brazil. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2014;5 doi: 10.4172/2155-9554.1000209. pii: 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rocha-Alvarez R, Friedman H, Campbell IT, Souza-Aguiar L, Martins-Castro R, Diaz LA. Pregnant women with endemic Pemphigus foliaceus (Fogo Selvagem) give birth to disease-free babies. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:78–82. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12611868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malek A, Sager R, Zakher A, Schneider H. Transport of immunoglobulin G and its subclasses across the in vitro-perfused human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(3 Pt 1):760–767. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Malek A. Ex vivo human placenta models: transport of immunoglobulin G and its subclasses. Vaccine. 2003;21:3362–3364. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aplin JD, Jones CJ, Harris LK. Adhesion molecules in human trophoblast - a review. I. Villous trophoblast. Placenta. 2009;30:293–298. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harris LK, Jones CJ, Aplin JD. Adhesion molecules in human trophoblast - a review. II. Extravillous trophoblast. Placenta. 2009;30:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daneshpazhooh M, Chams-Davatchi C, Valikhani M, Aghabagheri A, Mortazavizadeh SM, Barzegari M, et al. Pemphigus and pregnancy: a 23-year experience. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:534. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.82404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ross MG, Kane B, Frieder R, Gurevitch A, Hayashi R. Pemphigus in pregnancy: a reevaluation of fetal risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155:30–33. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Braunstein I, Werth V. Treatment of dermatologic connective tissue disease and autoimmune blistering disorders in pregnancy. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:354–363. doi: 10.1111/dth.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mimouni D, Nousari CH, Cummins DL, Kouba DJ, David M, Anhalt GJ. Differences and similarities among expert opinions on the diagnosis and treatment of Pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1059–1062. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(03)02738-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ramsey-Goldman R, Schilling E. Immunosuppressive drug use during pregnancy. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1997;23:149–167. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70320-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ostensen M, Ramsey-Goldman R. Treatment of inflammatory rheumatic disorders in pregnancy: what are the safest treatment options? Drug Saf. 1998;19:389–410. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199819050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Armenti VT, Moritz MJ, Davison JM. Drug safety issues in pregnancy following transplantation and immunosuppression: effects and outcomes. Drug Saf. 1998;19:219–232. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199819030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Connell W, Miller A. Treating inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy: risks and safety of drug therapy. Drug Saf. 1999;21:311–323. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199921040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vaughan Jones SA, Hern S, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Black MM. A prospective study of 200 women with dermatoses of pregnancy correlating clinical findings with hormonal and immunopathological profiles. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:71–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ahmed AR, Gurcan HM. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin therapy during pregnancy in patients with Pemphigus vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1073–1079. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sher G1, Zouves C, Feinman M, Maassarani G, Matzner W, Chong P, et al. A rational basis for the use of combined heparin/aspirin and IVIG immunotherapy in the treatment of recurrent IVF failure associated with antiphospholipid antibodies. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1998;39:391–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gurcan HM, Jeph S, Ahmed AR. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in autoimmune mucocutaneous blistering diseases: a review of the evidence for its efficacy and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:315–326. doi: 10.2165/11533290-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jolles S. A review of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (hdIVIg) in the treatment of the autoimmune blistering disorders. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:127–1231. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]