Abstract

Gynecomastia is an enlargement of male breast resulting from a proliferation of its glandular component, and it is usually due to an altered estrogen-androgen balance. It should be differentiated from pseudogynecomastia, which is characterized by fat deposition without glandular proliferation and from breast carcinoma. Gynecomastia could be physiological in neonates and pubertal or pathological due to drug intake, chronic liver, or renal disease, hyperthyroidism, testicular or adrenal neoplasms, and hypogonadism whether primary, or secondary. Properly organized work-up is needed to reach the cause of gynecomastia. Here, we reported a case of a young Omani man with gynecomastia with the aim of creating awareness of the occurrence of Klinefelter’s syndrome (KS) in patients with gynecomastia, to observe any differences in clinical presentation of KS from those reported in the literature, and highlight the needed diagnostic work-up and treatment.

Gynecomastia is an enlargement of male breast resulting from a proliferation of its glandular component. It is usually benign, bilateral, and characterized by the presence of a rubbery or firm mass around the nipples. It usually results from either increased estrogen level, increased breast sensitivity to estrogen,1 or low testosterone level. The highest incidence of gynecomastia is reported during neonatal period, puberty, and aging due to physiological disturbances. Pseudogynecomastia, which is often seen in obese men, refers to fat deposition without glandular proliferation and should be differentiated from gynecomastia. Therefore, male breast enlargement can be fatty (pseudogynecomastia or lipomastia), pure gynecomastia, or mixed. Our objective in presenting this particular case is to create awareness of the occurrence of Klinefelter’s syndrome (KS) in patients with gynecomastia, to observe any differences in clinical presentation of KS from those reported in the literature, and highlight the needed diagnostic work-up and treatment.

Case Report

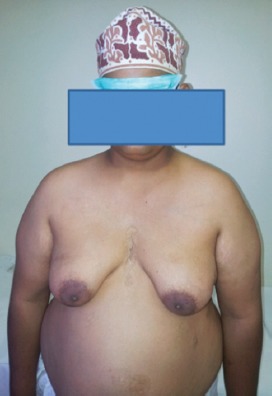

We report a 28-year-old single man with bilateral breasts enlargement, which was noticed since the age of 15 years. At the onset, it was painful, but the pain disappeared with time. No history suggestive of headache, visual changes, testicular trauma, or systemic or sexually transmitted diseases. Family, surgical and drug histories were unrevealing. On examination, he was obese (weight 89.8 Kg, height 159 cm, body mass index 35.9) and has an arm span of 165 cm. Systemic examination was unremarkable apart from mild hepatomegaly. Local examination revealed bilateral soft breast enlargement 14×10×10 cm (Figure 1), with non tender sub-areolar mass concentric, areola (3.5 x 3.5 cm), with regular borders, and free from underlying and overlying tissues. He has a little facial hair, scanty axillary and pubic hair, small and atrophic testes, and small non-buried penis. All routine biochemical reports were within normal limits. Hormonal assay revealed hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism on the basis of low serum total testosterone, high luteinizing hormone, and high follicle stimulating hormone with normal prolactin, estradiol, thyroid stimulating hormone, cortisol, beta human chorionic gonadotrophin, and alpha fetoprotein. Abdominal and pelvic CT was normal apart from fatty liver. Scrotal ultrasound showed significantly small testes, but with normal echotexture and shape. Bilateral ultrasound showed enlarged breasts, very small and difficulty visualized glandular tissue, normal nipples, areola, subcutaneous and fatty tissues, and axillary regions. Bilateral mammography showed predominantly fatty tissue and there were no masses, abnormal fibroglandular tissues, calcifications, or axillary lymph nodes. Semen analysis showed Azoospermia. Cytogenetic analysis, which showed 47 XXY karyotype diagnostic of Klinefelter’s syndrome (KS).

Figure 1.

A photograph of an obese male with bilateral breast enlargement.

Discussion

Gynecomastia was classified by Simon into several categories based on the size of the breast and skin redundancy.2 Pathological causes of gynecomastia include drug intake, chronic liver or renal disease, hyperthyroidism, adrenal neoplasms or hypogonadism whether primary as KS or secondary. Furthermore, the prevalence of gynecomastia increases with an increase in the body mass index, probably due to the paracrine effects of estradiol produced by subareolar fat on glandular tissue.3 In other cases, gynecomastia is idiopathic where no cause could be identified. Our patient is obese and has a Grade 3 mixed gynecomastia. His little facial hair guided us to carry out complete examination and further work-up, which revealed scanty axillary and pubic hair, small and atrophic testes, small penile size, eunuchoidal build (arm span longer than height), and hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism. Klinefelter’s syndrome was confirmed by cytogenetic analysis. Klinefelter’s syndrome is found in approximately 0.1-0.2% of the male population, and it presents differently according to the age. Before puberty, usually, no findings can be detected although slightly smaller testicular volume is sometimes noticed. However, after puberty, KS presents with signs and symptoms of androgen deficiency and infertility.4 Only 10% of cases were identified prenatally, 26% were diagnosed in childhood or adult life, leaving 64% undiagnosed.5 Therefore, a high index of suspicion is thus required to make clinical diagnosis. Patients with KS accounts for 4% of male breast-cancer cases and 20 times higher risk of breast cancer than males without KS.6 The cornerstone treatment of KS is by sufficient testosterone replacement, which should be started as early as possible.7 Intracytoplasmic sperm injection technique offers a hope for fertility and live births.8 Some patients with KS might need mastectomy for cosmetic purposes and increased cancer risk.7

In conclusion, KS is the most common genetic cause of human male infertility and should be considered in patients with gynecomastia and hypogonadism. Many cases are missed due to poor clinical suspicion, diverse clinical presentation, and difficult accessibility of cytogenetic analysis in some countries. Early diagnosis and hormonal replacement can virtually improve the quality of life and prevent serious complications. We highlight this case because our patient is obese and breast enlargement could be explained as pseudogynecomastia, and this low suspicion index may interfere with further diagnostic work-up.

Footnotes

Case Reports.

Case reports will only be considered for unusual topics that add something new to the literature. All Case Reports should include at least one figure. Written informed consent for publication must accompany any photograph in which the subject can be identified. Figures should be submitted with a 300 dpi resolution when submitting electronically or printed on high-contrast glossy paper when submitting print copies. The abstract should be unstructured, and the introductory section should always include the objective and reason why the author is presenting this particular case. References should be up to date, preferably not exceeding 15.

References

- 1.Glass AR. Gynecomastia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1994;23:825–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samdal F, Kleppe G, Amland PF, Abyholm F. Surgical treatment of gynaecomastia. Five years’ experience with liposuction. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1994;28:123–130. doi: 10.3109/02844319409071189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgiadis E, Papandreou L, Evangelopoulou C, Aliferis C, Lymberis C, Panitsa C, et al. Incidence of gynaecomastia in 954 young males and its relationship to somatometric parameters. Ann Hum Biol. 1994;21:579–587. doi: 10.1080/03014469400003582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanfranco F, Kamischke A, Zitzmann M, Nieschlag E. Klinefelter’s syndrome. Lancet. 2004;364:273–283. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16678-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramsky L, Chapple J. 47,XXY (Klinefelter syndrome) and 47, XYY: estimated rates of and indication for postnatal diagnosis with implications for prenatal counselling. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17:363–368. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199704)17:4<363::aid-pd79>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smyth CM, Bremner WJ. Klinefelter syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1309–1314. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.12.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen H, Windle ML, Starr LJ. Klinefelter syndrome. [Updated: 2015 July 1; Accessed 2013 August 22]. Available from URL: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/945649-overview .

- 8.Ron-El R, Raziel A, Strassburger D, Schachter M, Bern O, Friedler S. Birth of healthy male twins after intracytoplasmic sperm injection of frozen-thawed testicular spermatozoa from a patient with nonmosaic Klinefelter syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:832–833. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00710-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]