Abstract

Biallelic mutations in the gene encoding centrosomal CDK5RAP2 lead to autosomal recessive primary microcephaly (MCPH), a disorder characterized by pronounced reduction in volume of otherwise architectonical normal brains and intellectual deficit. The current model for the microcephaly phenotype in MCPH invokes a premature shift from symmetric to asymmetric neural progenitor-cell divisions with a subsequent depletion of the progenitor pool. The isolated neural phenotype, despite the ubiquitous expression of CDK5RAP2, and reports of progressive microcephaly in individual MCPH cases prompted us to investigate neural and non-neural differentiation of Cdk5rap2-depleted and control murine embryonic stem cells (mESC). We demonstrate an accumulating proliferation defect of neurally differentiating Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC and cell death of proliferative and early postmitotic cells. A similar effect does not occur in non-neural differentiation into beating cardiomyocytes, which is in line with the lack of non-central nervous system features in MCPH patients. Our data suggest that MCPH is not only caused by premature differentiation of progenitors, but also by reduced propagation and survival of neural progenitors.

Keywords: CDK5RAP2, MCPH, mental retardation, neural differentiation, primary microcephaly, stem cell

Abbreviations

- Cdk5rap2

Cyclin-dependent kinase-5 regulatory subunit-associated protein 2

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- MCPH

autosomal recessive primary microcephaly

- NPCs

neuroepithelial progenitor cells

- mESC

murine embryonic stem cells

- mLIF

murine leukemia inhibitory factor

- qPCR

quantitative real-time PCR.

Introduction

Autosomal recessive primary microcephaly (MCPH) is a rare neurodevelopmental disease characterized by intellectual disability and pronounced reduction in brain volume.1 The latter affects disproportionally the cerebral cortex, rendering MCPH a model disorder for neocortical development. The prevailing model for the microcephaly phenotype of MCPH invokes a stem cell defect with a premature shift of progenitor cell cleavage planes and subsequently of symmetric to asymmetric cell divisions. This entails premature neurogenesis, a depletion of the progenitor pool, and a reduction of the final number of neurons.1-4 A shift of the cleavage plane is most likely not the only underlying mechanism as microcephaly still occurs in MCPH mouse models where the cleavage plane is unaltered.5,6

Specifically, for MCPH caused by biallelic mutations of the cyclin-dependent kinase-5 regulatory subunit-associated protein 2 gene CDK5RAP2,7-10 underlying mechanisms include a deregulation of CDK5RAP2 in centrosome function, spindle assembly and orientation, and/or response to DNA damage (reviewed in refs. Eleven, 12). We recently described mitotic spindle defects, lagging chromosomes, and abnormal centrosomes in patient-derived lymphoblastoid cells.10 Cdk5rap2 mutant or Hertwig's anemia mice have small brains and thin cortices already at early stages of neurogenesis during embryonic development.2 These mice demonstrate abnormal morphology and orientation of mitotic spindles in progenitors with putative shift from symmetric to asymmetric divisions and a predisposition to chromosomal aneuploidy.2 Moreover, they display phenotypes suggestive of a delay in mitotic progression, an early exit from the cell cycle, a decrease of progenitors as development proceeds, and increased apoptosis of progenitors and neurons prior to and at the onset of neurogenesis.2 While Cdk5rap2 downregulation through shRNAi in vivo was likewise associated with decreased cell proliferation, early cell cycle exit, and increased premature neuronal differentiation, apoptosis was not increased.3

Data from early studies using Hertwig's anemia mice, when these mice were known only for their haematopoietic phenotype and not for microcephaly, indicate accumulating proliferation defects and cell death of differentiating stem cells. In this line, anemia was reported to result from a ‘loss’ of cells during erythroid differentiation of pluripotent stem cells, rather than from proliferation defects of multi- or pluripotent stem cells.13 In addition, a significant decrease of mitosis and a massive increase in germinal cell degeneration was reported during embryonic development of testes and ovaries.14

In addition to popular models and based on previous data, we hypothesized that microcephaly in MCPH is caused by the accumulation of 2 defects, an accumulating proliferation defect of differentiating neural stem cells and from cell death of differentiating and early postmitotic cells. To study the stem cell defect in MCPH caused by CDK5RAP2 dysfunction, we generated stable Cdk5rap2-depleted murine embryonic stem cell (mESC) lines through lentivirus infection. In the present study, we report the cellular consequences of a loss of Cdk5rap2 in mESC. We are thereby able to attribute the microcephaly phenotype in MCPH3 at least partially to a defect of neural mESC proliferation, survival, and differentiation. We further demonstrate that this effect is present in neural differentiation, but not in non-neural mESC differentiation into beating cardiomyocytes.

Results

To characterize the role of CDK5RAP2 in mESC proliferation and differentiation and thereby also of a stem cell defect in the microcephaly and intellectual disability phenotype of MCPH, we studied the expression of Cdk5rap2 in mESC and the effect of a stable shRNAi-lentivirus induced Cdk5rap2 depletion.

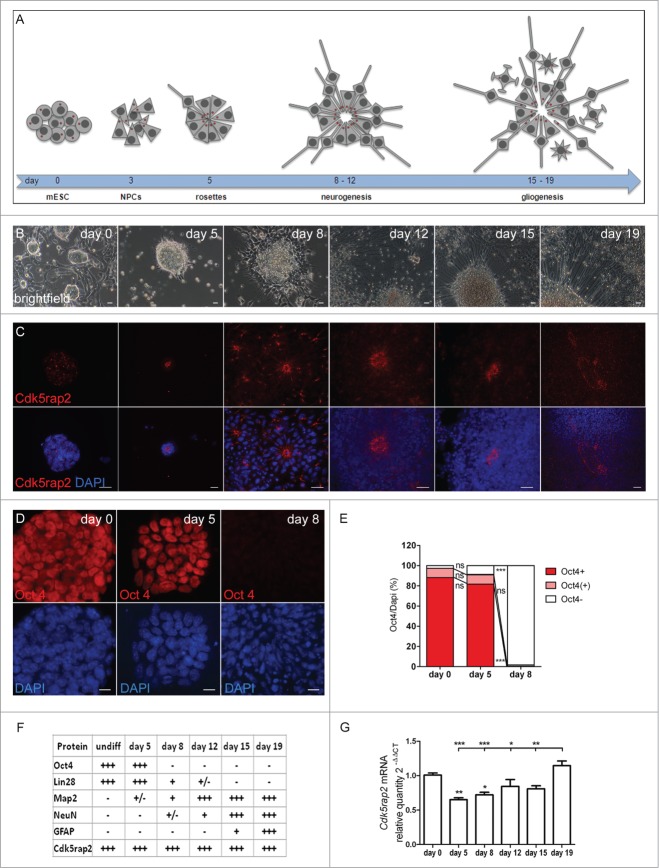

Neural differentiation of mESC

mESC maintained in an undifferentiated, proliferating state in the presence of mLIF form colonies, i.e. tight clusters of cells with well-defined boundaries (Fig. 1A–C). About 97% of these colonies were immunopositive for the stem cell marker Oct4 (Fig. 1D, E). For induction of neural differentiation, we applied a protocol that enables a neural differentiation in adherent monolayers through removal of mLIF and FBS in a defined medium rather than additional steps of EB formation in suspension cultures (Fig. S1A).15-17 This method avoids a selection of subpopulations through re-plating of cells during differentiation and thereby rather integrates all developing cells and cell types in a culture.15 Following differentiation induction on day 1, cells were proliferating and formed cell clusters that progressively organized in rosette-like structures by day 5 and began to extend first processes by day 8 (Fig. 1A, B). A compact network of processes sprouting from neuronal and glial cells within expanded rosette-like cell clusters was visible on days 12, 15, and 19 (Fig. 1A, B). These rosettes consist of radially arranged neuroepithelial progenitor cells (NPCs), which have an apico-basal polarity and are comparable with NPCs in the embryonic neural tube.16 On day 5, about 91% of these cell clusters contained highly Oct4-positive cells, while at day 8 nearly all of them (98%) were Oct4-immunonegative (Fig. 1D, E). Map2-positive, early neurons were first detected between days 5 and 8 (Figs. 1F and 2A) and had increased strongly by day 12. NeuN-positive, mature neurons were first detected in the periphery of rosette-formations between days 8 and 12 (Figs. 1F and 2B; Fig. S2) with increasing numbers on the following days. Single cells, positive for the astrocyte marker GFAP were identified on day 15 with increasing numbers on day 19 (Figs. 1F and 2C). Cells in the center of rosettes remained proliferative, thereby establishing large cell clusters (data not shown).

Figure 1 (See previous page).

Neural differentiation of mESC. (A–C) Scheme, phase contrast microscopy pictures, and immunocytochemistry of successive phases and cellular stages during neural differentiation of mESC. (A) Undifferentiated mESC formed colonies. After neural differentiation induction, pluripotent mESC developed into neuroepithelial precursor cells (NPCs). By day 5, these NPCs were organized in rosette-formations, giving rise to developing neurons around days 8 to 12 (neurogenesis) and to astrocytes by day 15 (gliogenesis). Processes extended from the cell clones by day 8, sprouted further and formed networks around day 12, resulting in a compact network of neuronal and glial fibers by day 19. Cells in the center of rosettes still proliferated, thereby establishing large cell clusters. Red dots depict centrosomes. (B) Phase contrast microscopy images illustrating morphological changes of mESC during neural differentiation. Scale bars 20 μm. (C) Cdk5rap2 (red) adopted a strongly polarized position in the center of rosettes from day 5 to day 12; this formation slowly disappeared around day 15. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Immunofluorescence images, scale bars 20 μm. (D) mESC were immunopositive for the stem cell marker Oct4 (red) on days 0 and 5, but not on day 8 after neural differentiation induction. DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Immunofluorescence images, scale bars 10 μm. (E) On day 0 and 5 about 97% and 91%, respectively, of all cell groups were Oct4-immunopositive (n = 3 per group, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison Test), while at day 8 nearly all of them (98%) were immunonegative. (F) Presence of cells positive for Cdk5rap2, stem cell markers (Oct4, Lin28) and markers for differentiated cells (Map2, NeuN, Gfap) during neural differentiation analyzed by immunocytochemistry: -, not present; +/−, first positive cells detectable; +, some positive cells; +++, many positive cells. (G) Cdk5rap2 mRNA levels, analyzed by qPCR, in undifferentiated mESC and during neural differentiation in vitro (n=6 per group, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison Test). Cdk5rap2 expression decreased at the beginning of differentiation and rose again, especially at the later stage (day 19) when astrocytes appeared in the differentiating mESC culture. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

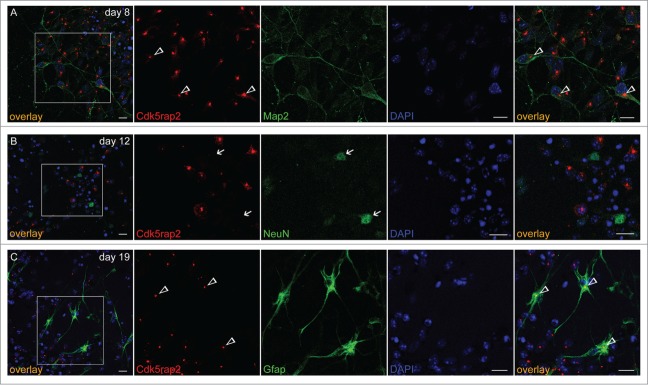

Figure 2.

Cdk5rap2 in neurons and glial cells. Cdk5rap2 (red) was present in postmitotic cells immunopositive for (A) Map2 (green; marker for early neurons) and (C) Gfap (green; marker for glial cells), but not in (B) NeuN-positive cells (green; marker for mature neurons). Arrowheads, Cdk5rap2-positive centrosomes; arrows, NeuN-positive and Cdk5rap2–negative cells; confocal images, scale bars 10 μm.

Cdk5rap2 in undifferentiated mESC and throughout neural differentiation

In undifferentiated mESC, Cdk5rap2 localized to the centrosome throughout the cell cycle and co-localized with γ-tubulin and pericentrin (Fig. S3A, B). During inter- and prophase, Cdk5rap2 further accumulated in close vicinity to the cis-Golgi matrix protein marker GM130 with no clear co-localization as reported in HeLa cells18 (Fig. S3C). This result is consistent with our previous finding in human lymphoblastoid cells.10

Upon neural differentiation and the formation of rosette-like structures with highly polarized cells, Cdk5rap2 still co-localized with centrosome markers and adopted a strongly polarized position within the cells by day 8 (Fig. 1A, C; Fig. S4A). This position was first detected on day 5, when 3 main types of cell agglomerations could be detected: (i) those still expressing the stem cell marker Oct4 and without a polarized position of Cdk5rap2, (ii) those organized in rosettes which were already negative for Oct4, had thus lost their pluripotent stem cell character, and showed a strongly polarized Cdk5rap2 position, and (iii) an intermediate type just beginning to organize in rosettes and still partially Oct4-positive (Fig. 1E). Specifically, Cdk5rap2 signals assembled in the center of rosettes, reflecting the apical localization of centrosomes in the polarized NPCs.16 Again, Cdk5rap2 was localized in close proximity to the cis-Golgi marker GM130, which was arranged radially veering toward the center of rosette-formations (Fig. 4B). Acetylated α-tubulin-positive primary cilia originated from Cdk5rap2-stained basal centrosomes, possibly acting as basal bodies, and extended into the lumen of the rosette formations (Fig. 4C). Rosette formations develop into large 3-dimensional cell groups through ongoing proliferation of NPCs. Cdk5rap2 further assembles in the center of these cell groups, forming large spherical clusters, which subsequently disassemble between days 15 and 19 (Fig. 1A, C). We detected Cdk5rap2 in progenitors, Map2-positive early neurons, and GFAP-positive astrocytes, but not in NeuN-positive mature neurons (Fig. 2). This is consistent with our previous results in the developing and adult murine neocortex.19 Cdk5rap2 expression as detected by qPCR decreases at the beginning of differentiation and rises again in later stages of neural differentiation parallel to gliogenesis (Fig. 1G).

Figure 4.

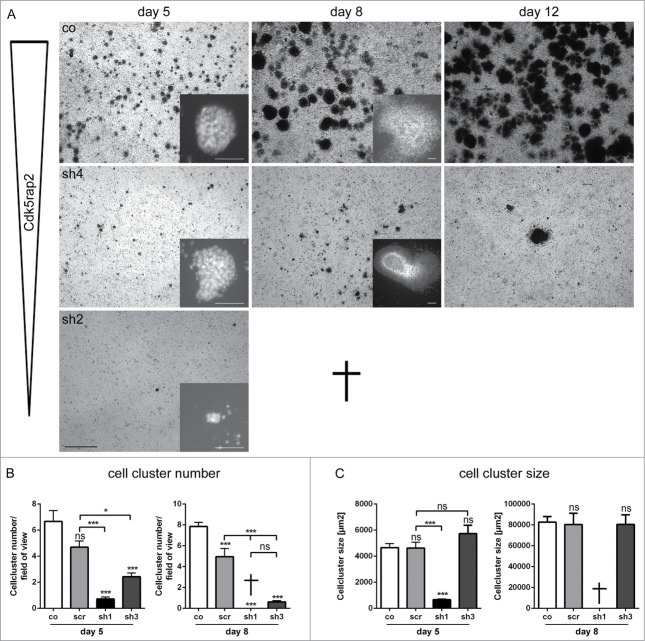

Loss of mESC cell culture during neural stem cell differentiation through strong Cdk5rap2 downregulation. (A) Low magnification of mESC culture growth after neural differentiation induction depicted complete loss of clone sh2 (similar results for sh1, data not shown) and only few surviving cell groups in clone sh4 (similar results for sh3, data not shown). Pictures of day 15 and 19 are similar to day 12; results for scr are similar to co (data not shown). Phase contrast microscopy pictures, black scale bar 1 mm. Inset pictures show representative cell clusters in higher magnification. White scale bars 50 μm. (B) Cell cluster number and (C) size at day 5 and 8 of neural differentiation (n = 6 per group, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison Test). At day 5, cell cluster number and size was strongly reduced in clones with strongly downregulated Cdk5rap2 (sh1, sh2). Cell clusters of clones with intermediately downregulated Cdk5rap2 (sh3, sh4) were reduced in number, but not in size. At day 8, cultures of clones sh1 and sh2 were completely lost. In cultures of clones sh3 and sh4 few cell clusters with normal size were present. Abbreviations: Co, control; scr, scramble; sh1–4, shRNAi clones 1–4; ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Generation of stable Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC

To study the stem cell defect hypothesized to cause MCPH, we generated stable Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC lines. For this, we infected mESC with 4 Cdk5rap2 shRNAi lentivirus constructs A-D or a scramble sequence (Fig. S5A). We detected a significant downregulation of Cdk5rap2 with constructs B, C, and D when compared to the effect of the scramble shRNAi construct, through qPCR and immunocytology (Fig. S5A, B). The most efficient Cdk5rap2 downregulation occurred when mESC were infected with shRNAi construct B. To reduce variability of the Cdk5rap2 downregulation efficiency between cell clusters within one cell culture, we established 16 single clone-derived cultures from mESC infected with the shRNAi construct B (Fig. S5C). Downregulation of Cdk5rap2 mRNA in these cultures was confirmed through qPCR (Fig. S5D). Four clones were selected for further studies, the 2 clones sh1 and sh2 with a strong downregulation of Cdk5rap2 mRNA to about 20% and the 2 clones sh3 and sh4 with intermediate downregulation to about 40% of normal RNA levels (Fig. S5F). The findings established through qPCR were consistent with our findings when we analyzed these cultures via Western blot and immunocytology (Fig. S5E–G). Notably, in mitotic cells, a faint centrosomal Cdk5rap2 immunopositivity was present even in clones with strong downregulation of Cdk5rap2.

Cdk5rap2 downregulation causes proliferation defect of undifferentiated mESC

Because CDK5RAP2 impacts on human brain size and has been associated with progenitor proliferation, we next sought to examine the effect of Cdk5rap2 downregulation on mESC proliferation, cell survival, cell cycle, and the integrity of the centrosome and the mitotic spindle apparatus in shRNAi-treated mESC. Cdk5rap2 co-localized with the centrosomal protein γ-tubulin throughout the cell cycle in control mESC (Fig. S6A). In shRNAi mESC sh1 and sh2 with strong downregulation of Cdk5rap2, we detected a more diffuse γ-tubulin staining around the centrosome, while total γ-tubulin levels were not reduced as detected through Western blot (Fig. S6A–C). Pericentrin localization was normal in Cdk5rap2 shRNAi mESC when compared to control mESC, and we did not detect spindle defects (data not shown). Cdk5rap2 shRNAi caused decreased rates of cell culture growth that was mainly due to a reduction of proliferation of undifferentiated mESC, which correlated in severity with the degree of Cdk5rap2 reduction (Fig. 3A–C). Apoptosis rates differed among the 4 shRNAi clones and could not be correlated with Cdk5rap2 presence in mESC (Fig. 3D, data not shown). As Cdk5rap2 knockdown has been reported to cause increased cell cycle exit leading to premature neuronal differentiation in vivo,3 we analyzed cell cycle distributions of undifferentiated mESC clones by flow cytometry. They showed similar proliferation (similar S-phase fractions) of vital cells comparing sh1–4, scramble, and control (Fig. S7A). In control mESC we observed beginning/first fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus stacks in prometaphase and subsequent dispersion of small Golgi vesicles in the cytoplasm until reassembly in the 2 forming daughter cells during telophase (Fig. S3C). This is consistent with previous reports in HeLa cells.20,21 Analysis of the Golgi integrity through immunostaining with the cis-Golgi marker GM130 revealed a premature Golgi fragmentation during mitosis in the mESC clone with strongly downregulated Cdk5rap2 (sh2) (Fig. S8). In contrast to control mESC, in which the Golgi apparatus fragmentation began in prometaphase and reassembly occurred in the daughter cells during cytokinesis, in clone sh2, the Golgi fragmented earlier in prophase and had already disappeared by prometaphase. In mESC with intermediate Cdk5rap2 downregulation (sh3), the timing was similar to control mESC. This result is in line with our findings in cultured immortalized lymphoblasts from patients with MCPH3.10 In addition, Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC did not show increased sensitivity to cell-stress applied through treatment with the apoptosis inducing substances22,23 H2O2 or staurosporine (Fig. S7B).

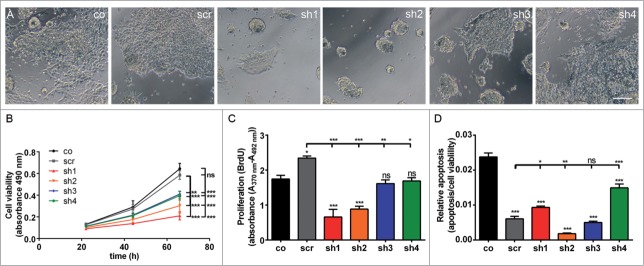

Figure 3.

Proliferation defect of undifferentiated mESC with Cdk5rap2 downregulation, but no enhanced spontaneous apoptosis. (A) Phase contrast microscopy pictures of cultures at DIV3; note the reduced density and size of cell clusters particularly for clones sh1 and sh2. Scale bar 100 μm. (B) Cell viability of undifferentiated mESC days in vitro (DIV) 1–3 of culturing (n = 4 −12 per group, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison Test) demonstrated a reduced growth of Cdk5rap2 shRNAi cell cultures. (C) Proliferation and (D) relative apoptosis of undifferentiated mESC at DIV3 (n = 4 −6 per group, one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001, Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison Test). Proliferation was strongly or moderately reduced for strongly (sh1 and sh2) or intermediately Cdk5rap2-downregulated clones (sh3 and sh4), respectively. Apoptosis varied between shRNAi clones and was not increased compared to control cells at DIV3. Abbreviations: Co, control; scr, scramble; sh1–4, shRNAi clones 1–4; ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Cdk5rap2 downregulation causes a severe proliferation defect and apoptosis during neural mESC differentiation

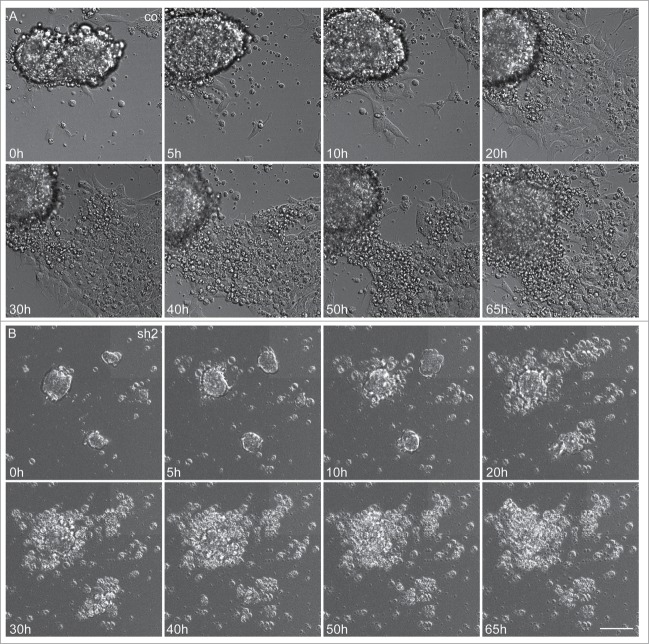

Induction of neural differentiation of strongly Cdk5rap2-downregulated mESC clones resulted in a strong decrease of proliferation rates and cell survival as well as a failure of rosette-formation. Cdk5rap2 shRNAi mESC clones with strong Cdk5rap2 downregulation (sh1, sh2) did not survive differentiation (Fig. 4A). Here, cell cluster numbers and cell cluster sizes were reduced strongly on day 5 and cultures had disintegrated by day 8 (Fig. 4A–C). We therefore also analyzed clones with intermediate Cdk5rap2 downregulation (sh3, sh4), which were still viable at day 19 (Fig. 4A, data not shown). In these clones, cell clusters were also significantly reduced in number but not in size at day 5 and day 8 (Fig. 4A–C). Only few ‘cell aggregates’ had formed by day 12. Live-cell imaging recordings confirmed that the main defect in Cdk5rap2-depleted cultures emerged already by day 3 of neural differentiation (Fig. 5A, B, Movies S1 and S2): In control cultures, cells proliferated rapidly, and subsequently migrated into the periphery while still keeping contact to adjacent cells, leading to an expansion of the cell clusters and the formation of monolayers between cell clusters. Cdk5rap2-depleted cell clusters were already much smaller on day 3 of neural differentiation with cells at the edge of these clusters rapidly losing contact to adjacent cells and undergoing cell death. Thus, no cells migrating away from the cell clusters could be visualized, and by day 5 after differentiation induction no viable cells remained. We further analyzed proliferation, apoptosis, and growth behavior during this early phase of neural differentiation. Knockdown of Cdk5rap2 caused decreased rates of cell culture growth of differentiating mESC, which was both due to a reduction of proliferation and an increase of apoptosis (Fig. 6A, B). Apoptosis was particularly increased in the first days of neural differentiation (Fig. 6B).

Figure 5.

Severely reduced proliferation and apoptosis of neuroepithelial cells in Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC. Representative, sequential bright field live-cell imaging pictures starting at day 3 after differentiation induction (imaging 65h, pictures taken every 7 min, scale bar 50 μm). (A) In control cultures, cells proliferated rapidly, leading to an extension of the cell clusters, and subsequently migrated into the periphery while still keeping contact to adjacent cells. Monolayers between cell clusters were formed. (B) Cdk5rap2-depleted cell clusters were already much smaller at the beginning of live-cell imaging and cells at the edge of these clusters lost contact to adjacent cells and underwent cell death. Thereby, no viable cells were left at day 5 after differentiation induction (images 50 and 65 h), and no migrating cells were visible. Abbreviations: Co, control; scr, scramble; sh1–4, shRNAi clones 1–4.

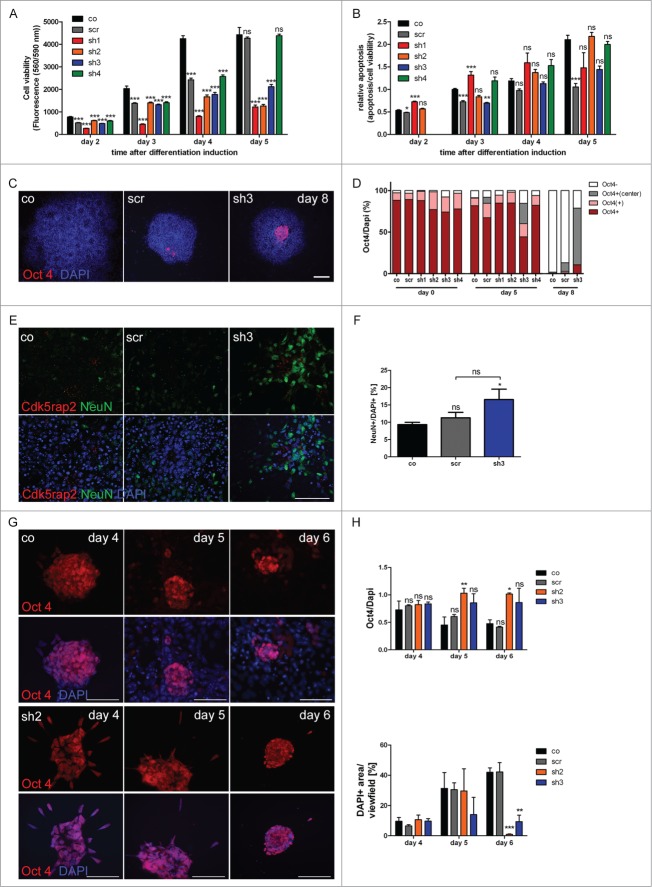

Figure 6 (See previous page).

Accumulating proliferation defect and apoptosis of neurally differentiating mESC. (A) Cell viability and (B) relative apoptosis of neurally differentiating mESC. Severely affected cell viability in clones with strongly downregulated Cdk5rap2 (sh1, sh2) as well as in clone sh3, becoming clearly apparent at day 5 after neural differentiation induction. Significant increase of apoptosis in clone sh1 on days 2 and 3 after differentiation induction. (C) Representative Immunofluorescence pictures at day 8 depicting the typical loss of Oct4-positivity (red) in control and scramble cell groups, while Cdk5rap2-downregulated clones still contained Oct4-positive cells in their center; DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar 100 μm. (D) Oct4 quantification of undifferentiated (day 0) mESC and at day 5 and 8 of neural differentiation (n = 3 per group, 2-way ANOVA, Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison Test). No significant differences in Oct4 staining were detected between the undifferentiated clones. At day 5 after differentiation induction, in clone sh3 significantly less cell groups were Oct4-positive (***P < 0.001), but significantly more cell groups with Oct4-positive cells in the center (**P < 0.01) were present compared to the control mESC. At day 8, in clone sh3 significantly less cell groups were Oct4-negative (***P < 0.001) compared to control/scramble mESC and significantly more were Oct4-positive (*P < 0.05) or had Oct4-positive cells in their center (***P < 0.001). No premature loss of Oct4-positivity was detected in Cdk5rap2-downregulated mESC. (E) In control and scramble cultures, NeuN-positive Neurons (green) were distributed harmoniously in the periphery of rosette-formations on day 15, while in downregulated clones they arranged in abnormal clusters (clone sh3, similar results for sh4, data not shown); Cdk5rap2 (red), DAPI (blue); confocal pictures, scale bar 50 μm. (F) Quantification of NeuN-positive cells relative to DAPI at day 15 after neural differentiation induction revealed an increase of NeuN-positive mature neurons in clone sh3. (G) No premature spontaneous differentiation of Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC. At day 6 after withdrawal of mLIF, cells in sh2 were still Oct4-positive (red), while most cells in the control were already Oct4-negative at day 5; DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). Immunofluorescence pictures, scale bars 50 μm. (H) Quantification of Oct4-positive cells during spontaneous differentiation after withdrawal of mLIF and amount of cells determined indirectly by measurement of DAPI-positive area per view field. At day 4 after withdrawal of mLIF no significant differences could be found between the control, scramble and shRNAi clones sh2 and sh3. At day5 and 6 the relative amount of Oct4-positive cells was significantly increased in the Cdk5rap2 strongly downregulated clone sh2, whereas the number of all DAPI-positive cells was dramatically reduced. Results for the clone with intermediate Cdk5rap2 downregulation (sh3) showed the same trend, but were not significant.

Cdk5rap2 downregulation affects neurogenesis

To verify the prevailing hypothesis of premature neurogenesis being a part of the MCPH pathomechanism, we analyzed loss of stem cell marker Oct4 and emergence of neuronal marker NeuN in Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC, control, and scramble. No premature loss of stem cell marker Oct4 appeared in the Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC when mLIF-treatment was discontinued to allow neural (Fig. 6C, D) or spontaneous (Fig. 6G, H) differentiation. Here, Oct4-positive cells were even discerned longer than in the control/scramble cultures when neural differentiation was induced (Fig. 6C, D) and also when cells differentiated spontaneously only by withdrawal of mLIF (Fig. 6G, H). While most cell clusters were already Oct4 negative in the controls on day 8 of neural differentiation, 68% of the surviving sh3 clones contained grouped Oct4-positive progenitors in their center (Fig. 6D). Similarly, in spontaneous mESC differentiation, the relative amount of Oct4-positive cells was increased significantly in sh2 and showed a trend toward an increase in sh3, when compared to control and scramble mESC by days 5 and 6 (Fig. 6H). Here, the total amount of cells was decreased significantly by day 6. While at this time about 42% confluent control and scramble cultures contained 41–48% Oct4-positive cells, the only 1–10% confluent sh2 and sh3 cultures had 86–100% Oct4-positive cells. These results indicate a loss of early differentiating cells in Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC upon spontaneous differentiation since cell death is increased in parallel to a (compensatory) increase of proliferating cells. This effect is even more severe in induced neural differentiation of strongly Cdk5rap2-depleted clones as none of these survive differentiation. In clone sh3, the fraction of cells expressing the neuron marker NeuN was increased at day 15 of neural differentiation when compared to the control situation (Fig. 6E, F), indicative of premature neurogenesis. NeuN-positive cells were arranged in abnormal clusters in the periphery of large, spherical cell agglomerates.

Cdk5rap2 downregulation does not affect non-neural differentiation into contracting cardiomyocytes

To study the effects of Cdk5rap2 downregulation on non-neural differentiation, the ability of the clones to differentiate via the cardiac lineage was investigated in differentiation assays of the validated embryonic stem cell test (EST),24 which exploits the ability of pluripotent mESC to differentiate into cardiac tissue upon removal of the cytokine mLIF. In the presence of fetal bovine serum, the cardiomyocyte lineage is the predominant differentiation route in mESC cells, resulting in contractile areas within the embryoid body (EB) outgrowth. In a number of studies it has been demonstrated that these cells share properties with major cardiac cell types (atrial-, ventricle-, purkinje-, and pacemaker-like cells), show functional electrophysiological activity, and display dose-dependent pharmacological responses to cardioactive drugs.25-28 Mesoderm-derived cardiomyocytes are among the first cells acquiring functionality in the embryo. The extent of differentiation in the EST assay is assessed as the number of beating EB outgrowths after 10 d of culture. Applying the criteria of the validated EST for normal cardiac differentiation that is at least 21 out of 24 wells containing contracting myocardial cells, cardiac differentiation was unaffected in the Cdk5rap2 shRNAi mESC clone with strong Cdk5rap2 downregulation (sh1) similar to that in control and scramble clones (Fig. 7).

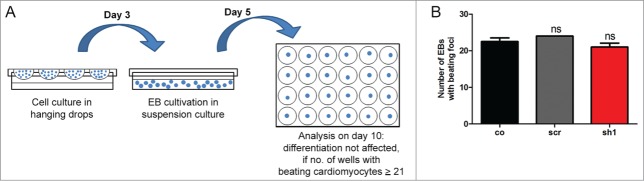

Figure 7.

Loss of Cdk5rap2 does not affect non-neural mESC differentiation into beating cardiomyocytes. (A) Scheme of assay to evaluate mESC differentiation into beating cardiomyocytes according to the validated embryonic stem cell test.24 (B) Normal cardiac differentiation was obtained for a Cdk5rap2 shRNAi mESC clone with strong Cdk5rap2 downregulation (sh1) as well as for control and scramble (n = 3 experiments, 24 wells each, one-way ANOVA, p = 0.1238, Bonferroni's Multiple Comparison Test, ns, not significant). Abbreviations: Co, control; scr, scramble; sh1–4, shRNAi clones 1–4; ns, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that microcephaly in MCPH3 results not only from a premature shift from symmetric to asymmetric mESC division and a subsequent depletion of the progenitor pool, but also from subsequent proliferation defects of differentiating stem cells and from cell death of proliferative and early postmitotic cells (Fig. 8). We further demonstrate that this effect occurs in neural but not in non-neural differentiation of stem cells.

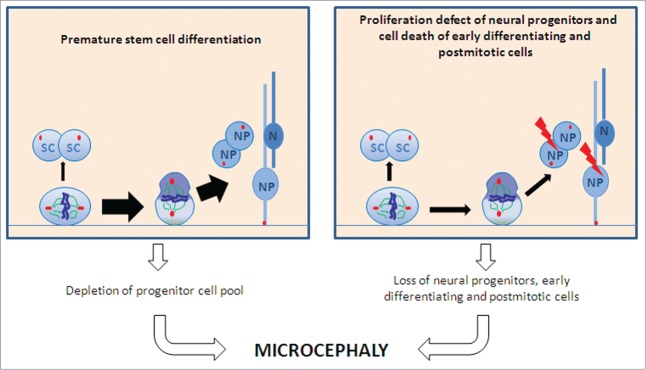

Figure 8.

Schematic of proposed pathomechanisms underlying microcephaly in MCPH. A premature shift from symmetric to asymmetric cell division with a subsequent depletion of the progenitor pool (left part) and proliferation defects of differentiating stem cells and cell death of proliferative cells and early postmitotic cells (right part) lead to microcephaly. Abbreviations: SC, stem cell; N, neuron; NP, neural precursor.

To study in detail the stem cell defect in MCPH caused by CDK5RAP2 dysfunction, we generated stable Cdk5rap2-depleted mESCs through lentivirus infection and analyzed their phenotype during neural and non-neural differentiation. This mESC culture-based model conveniently imitates neural development of MCPH patients through induction of neural differentiation of Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC (Figs. 1, 2, Fig. S5). We detected a slight proliferation defect already in undifferentiated, symmetrically proliferating Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC, which was not due to an enhanced sensitivity toward apoptosis inducing factors (Fig. 3, Fig. S7). We further detected a reduction of centrosomal but not of total γ-tubulin and a premature fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus (Figs. S6, S8). However, neither abnormal mitotic spindle morphology nor changes in cell cycle distribution could be detected in undifferentiated mESC (Fig. S7 and data not shown), while a premature cell cycle exit had been reported in more differentiated neural progenitors.2,3 Our findings are in line with previous reports in MCPH3 patient lymphoblastoid cells,10 in neuronal precursors of Hertwig's anemia mice,2 in Cdk5rap2 siRNA electroporated murine brains,3 and in various tumor cell lines.29-33

The most prominent effect of Cdk5rap2 downregulation in mESC was apparent after induction of neural differentiation, which resulted in a complete loss of cell cultures with strongly downregulated Cdk5rap2 (Figs. 4, 5, Movies S1 and S2). This defect was due to both a severe reduction in proliferation and an increase of apoptosis of early differentiating cells, NPCs. After induction of neural differentiation, proliferation of NPCs is essential for cell culture survival by producing a sufficient number of neurally differentiating cells. In Cdk5rap2-depleted cell cultures, the proliferation defect was increased strongly after differentiation induction. Furthermore, we detected cells ‘breaking out’ of their cell clusters, presumably by losing contact to adjacent cells and undergoing apoptosis. This severe proliferation defect is in line with previous descriptions of reduced apical progenitors and increased cell-cycle exit in the murine neocortex.2,3

Rosette formation after neural differentiation of mESC is acknowledged as a model for neural tube development in vivo, where pluripotent mESC develop into NPCs.16 The strict assembly of Cdk5rap2 at the centrosome and basal bodies of primary cilia in the center of rosettes and cell clusters during neural differentiation implies that Cdk5rap2 may play a role in the organization of these cell clusters. Here, the strongly ‘polarized’ positioning of Cdk5rap2 may be important for apical-basal polarity of NPCs, as described for other centrosomal proteins.34 Processes such as the polarization of differentiating NPCs are crucial for normal central nervous system development.35 This not only applies to neural progenitors where, e.g., the apical-basal polarity is key for sustaining interkinetic nuclear migration and thus maintaining the neural progenitor pool during neocortical development,36,37 but also to postmitotic cells such as neurons.38,39 Reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis of NPCs secondary to a loss of Cdk5rap2 can ultimately result in a reduced generation of neurons and subsequently in the microcephaly phenotype typical for MCPH. The increased proportion of NeuN-positive neurons at day 15 of neural differentiation in Cdk5rap2-reduced mESC in parallel to the reduction of the total number of cells in these cell cultures supports the hypothesis that microcephaly in MCPH3 results also from a temporary increase of progenitor differentiation leading to a depletion of the stem cell pool.

Given the current model that CDK5RAP2 mutations cause microcephaly not only via the temporarily increased differentiation of stem cells, but also through a premature shift from symmetric to asymmetric cell divisions and thus premature neurogenesis, we applied a protocol that enables spontaneous mESC differentiation after withdrawal of mLIF. We hereby investigated whether Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC generally tend to differentiate prematurely or if this is specific for neural differentiation. In spontaneous differentiation of mESCs, we detected neither a premature loss of stem cell markers (Fig. 6), nor a premature differentiation into beating cardiomyocytes (data not shown) in Cdk5rap2-depleted cell cultures. This indicates that Cdk5rap2 depletion does not lead to premature differentiation in all tissues.

Since biallelic CDK5RAP2 gene mutations cause an isolated brain phenotype in humans despite CDK5RAP2 expression in several tissues,2,40 we addressed the question whether Cdk5rap2 downregulation has a different effect on mESC differentiation into neurons and glial cells versus differentiation into beating cardiomyocytes. We demonstrate that non-neural differentiation into beating cardiomyocytes is not affected in mESC with strongly downregulated Cdk5rap2 with regard to the criteria of the validated EST (Fig. 7). This indicates that loss of Cdk5rap2 function does not affect differentiation in general, but must impair a mechanism, such as polarization, which is important for neural differentiation, but not for differentiation into cardiomyocytes. For non-neural tissues not affected in patients with MCPH, it can be speculated that loss of Cdk5rap2 can be in part compensated in progenitor proliferation and differentiation and/or that its role in those tissues is not as crucial for development.

Taken together, our results support our hypothesis that microcephaly in MCPH3 results not only from a premature differentiation as previously reported, but also from an accumulating proliferation defect of differentiating cells as well as from cell death of differentiating and early postmitotic cells. In view of the ‘isolated’ neurological phenotype of MCPH3 and with respect to the Cdk5rap2 localization during neural differentiation, it is most likely that Cdk5rap2 further plays a role in functions, which are exclusively important in neuronal development. Further studies are needed to enlighten the role and impact of Cdk5rap2 in these functions.

Materials and Methods

mESC culture

mESC (W4/129S6 originally developed by Wojtek Auerbach in the laboratory of Dr. Alexandra L. Joyner at the New York University School of Medicine) were cultured in maintenance medium, consisting of high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco, https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/41965039) supplemented with 15% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/10270106), 2 mM glutamine (Gibco, https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/25030024), 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco, https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/15140122), 1% nonessential amino acids (Gibco, https://www.lifetechnologies.com/order/catalog/product/11140035), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/m7522), and 1000 U/ml murine leukemia inhibitory factor (mLIF; Chemicon, http://www.merckmillipore.com/DE/de/product/ESGRO%C2%AE-Leukemia-Inhibitory-Factor-%28LIF%29%2C-1-million-units1-mL,MM_NF-ESG1106). The cytokine mLIF, which is known to sustain mESC self-renewal,41,42 was added to the medium to maintain the mESC in an undifferentiated, proliferating status. In addition, 2 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/p9620) was added to the medium of W4/scramble and W4/shRNAi cells to selectively culture those cells that stably express shRNA. Cells were passaged every second to third day.

mESC differentiation into neural cells

Neural differentiation was induced according to a modified protocol based on the method of Visan et al. 201215 (Fig. S1A). In addition, 1 μg/ml puromycin was added to the medium of W4/scramble and W4/shRNAi cells to selectively culture those cells that stably express shRNA.

mESC differentiation into contracting cardiomyocytes

To analyze the ability of mESC to differentiate via the cardiac route, differentiation assays were performed according to the validated protocol described previously24 (Fig. S1B).

Spontaneous mESC differentiation

For the spontaneous, non-directed differentiation of mESC through mLIF withdrawal, cells were plated in maintenance medium without mLIF. Medium was changed every second to third day (Fig. S1C).

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qPCR were performed with established methods.43 Primer and probe sequences and PCR conditions are given in Tables S1 and S2.

Protein extraction procedure and Western blot

Protein extraction and Western blot was performed with established methods. A comprehensive list of antibodies is given in Table S3.

Immunocytology

Coverslips were incubated in 4% PFA for fixation and subsequently in staining buffer (0.2% gelatin, 0.25% triton X-100, 10% donkey normal serum in PBS 1x; Sigma-Aldrich, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/g2500, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/t8787, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/d9663) for 30 minutes at RT for blocking. Coverslips were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies in the staining buffer followed by an incubation with the corresponding secondary antibodies for 2 hours at RT. Nuclei were labeled with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/d9542). See Table S3 for a comprehensive list of antibodies and concentrations.

Lentivirus shRNAi, stable Ckd5rap2-depleted mESC, and establishment of isolated mESC clone cultures

To establish cell lines with stable Cdk5rap2 downregulation, mESC were infected with Cdk5rap2 MISSION® shRNAi lentiviral transduction particles (shRNAi-A: GCACATCTACAAGACGAACAT; shRNAi-B: GCCATCAAGATACGATTCATT; shRNAi-C: CCTCAAGACTTACTAATGGAA; shRNAi-D: CGTGAGATCATGGAGGACTAT; Sigma-Aldrich, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/genes/CDK5RAP2). In addition, MISSION® non-target shRNAi control transduction particles representing a scramble control were used as a negative infection control. The infection was performed according to a modified protocol from the manufacturer (Fig. S1D). To establish homogeneous Cdk5rap2-depleted mESC clones (Fig. S1E), single clone-derived colonies from a culture infected with Cdk5rap2 shRNAi clone B were isolated by picking each of them with a glass Pasteur pipette and transferring them individually to a separate well of a 96-well plate. Colonies were expanded for 10 d before aliquots were used for RNA-extraction and immunostaining to analyze the efficiency of Cdk5rap2 downregulation. For all further experiments a not infected control (co) and the scramble control (scr) were used in parallel to Cdk5rap2-depleted clones.

Quantification of cell cluster size and number

For quantification studies, cells were fixed at day 5 and 8 after neural differentiation induction, and nuclei were labeled with DAPI. From each sample, 7 pictures were taken using a 10x objective, providing a 2.312 mm2 view area. Number and size of cell groups were calculated using ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Quantification of cell viability, apoptosis, and proliferation

Cell viability was quantified using the MTS-based CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, https://www.promega.de/products/cell-health-and-metabolism/cell-viability-assays/celltiter-96-aqueous-one-solution-cell-proliferation-assay-_mts_/), the Fluorimetric CellTiter-Blue® Cell Viability Assay (Promega, https://www.promega.de/products/cell-health-and-metabolism/cell-viability-assays/celltiter_blue-cell-viability-assay/), and/or by counting the cells using a Neubauer hemocytometer. Apoptosis and proliferation were assessed by multiplexing with the ApoONE® Homogeneous Caspase-3/7 Assay (Promega, https://www.promega.de/products/cell-health-and-metabolism/apoptosis-assays/fluorometric-and-colorimetric-caspase-assays/apo_one-homogeneous-caspase_3_7-assay/) and by using the colorimetric Cell Proliferation BrdU-ELISA (Roche Diagnostics, http://lifescience.roche.com/shop/products/cell-proliferation-elisa-brdu-colorimetric-), respectively, according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Spontaneous and induced apoptosis assays

To determine the sensitivity of cell clones toward apoptosis-inducing agents, cells were treated with staurosporine (0.2 μM; Tocris, http://www.tocris.com/dispprod.php?ItemId=1570#.VNM-96Mwe70) or H2O2 (300 μM, Sigma-Aldrich, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/product/sigma/h1009) for 18 h, and cell viability, apoptosis, and proliferation were analyzed as described above.

Live-cell imaging

For live-cell imaging at early stages of neural differentiation, mESC were plated on 35 mm Fluoro dish cell culture dishes (World Precision Instruments, http://www.wpi-europe.com/products/cell-and-tissue/fluorodish-cell-culture/fd35–100.aspx) at day 1 of neural differentiation. Images were collected every 7 minutes with an exposure time of 100–135 ms over a time period of 68 hours (day 3 to 6 of neural differentiation) using the Axio Observer Z1 platform (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, http://www.zeiss.de/microscopy/de_de/home.html) with a plan-apochromat 20x/0.8 M27 objective.

Cell cycle analysis

For cell cycle analysis, cells were detached with trypsin 0.05% and EDTA 0.02%, pelleted and stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI in a buffer containing 154 mM NaCl, 0.1 M TRIS pH 7.4, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2% BSA, and 0.1% NP40. Univariate flow histograms were recorded on a triple-laser equipped LSRII flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, http://www.bdbiosciences.com/eu/bd-lsr-ii/c/744818) using UV excitation. Data was quantified with the MPLUS AV software package (Phoenix Flow Systems, http://www.phnxflow.com/).

Imaging

Phase contrast microscopy pictures were taken with an AxioVert 40 CFL microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy), fluorescently labeled cells were imaged with a fluorescent Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, http://www.olympus-ims.com/de/microscope/bx51p/), and confocal-microscopy images were taken by an lsm5exciter Zeiss confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy). All images were processed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc.., http://www.adobe.com/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Victor Tarabykin, Gregory Wulczyn, Robert Nitsch, Richard Friedl, Gisela Stoltenburg-Didinger, Julia König, Jessica Fassbender, Birgitta Slawik (differentiation assays of the validated EST), and Susanne Kosanke for discussions and technical assistance.

Funding

Our research was supported by the German Research Foundation (SFB665), the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH), the Sonnenfeld Stiftung, and the DAAD.

References

- 1.Kaindl AM, Passemard S, Kumar P, Kraemer N, Issa L, Zwirner A, Gerard B, Verloes A, Mani S, Gressens P.. Many roads lead to primary autosomal recessive microcephaly. Prog Neurobiol 2010; 90:363-83; PMID:19931588; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lizarraga SB, Margossian SP, Harris MH, Campagna DR, Han AP, Blevins S, Mudbhary R, Barker JE, Walsh CA, Fleming MD.. Cdk5rap2 regulates centrosome function and chromosome segregation in neuronal progenitors. Development 2010; 137:1907-17; PMID:20460369; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.040410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchman JJ, Tseng HC, Zhou Y, Frank CL, Xie Z, Tsai LH.. Cdk5rap2 interacts with pericentrin to maintain the neural progenitor pool in the developing neocortex. Neuron 2010; 66:386-402; PMID:20471352; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fish JL, Kosodo Y, Enard W, Paabo S, Huttner WB.. Aspm specifically maintains symmetric proliferative divisions of neuroepithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:10438-43; PMID:16798874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0604066103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pulvers JN, Bryk J, Fish JL, Wilsch-Brauninger M, Arai Y, Schreier D, Naumann R, Helppi J, Habermann B, Vogt J, et al.. Mutations in mouse Aspm (abnormal spindle-like microcephaly associated) cause not only microcephaly but also major defects in the germline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:16595-600; PMID:20823249; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1010494107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fietz SA, Huttner WB.. Cortical progenitor expansion, self-renewal and neurogenesis-a polarized perspective. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2011; 21:23-35; PMID:21036598; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.conb.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond J, Roberts E, Springell K, Lizarraga SB, Scott S, Higgins J, Hampshire DJ, Morrison EE, Leal GF, Silva EO, et al.. A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size. Nat Genet 2005; 37:353-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassan MJ, Khurshid M, Azeem Z, John P, Ali G, Chishti MS, Ahmad W.. Previously described sequence variant in CDK5RAP2 gene in a Pakistani family with autosomal recessive primary microcephaly. BMC Med Genet 2007; 8:58; PMID:17764569; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2350-8-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pagnamenta AT, Murray JE, Yoon G, Sadighi Akha E, Harrison V, Bicknell LS, Ajilogba K, Stewart H, Kini U, Taylor JC, et al.. A novel nonsense CDK5RAP2 mutation in a Somali child with primary microcephaly and sensorineural hearing loss. Am J Med Genet A 2012; 158A:2577-82; PMID:22887808; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ajmg.a.35558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Issa L, Mueller K, Seufert K, Kraemer N, Rosenkotter H, Ninnemann O, Buob M, Kaindl AM, Morris-Rosendahl DJ.. Clinical and cellular features in patients with primary autosomal recessive microcephaly and a novel CDK5RAP2 mutation. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013; 8:59; PMID:23587236; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1750-1172-8-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraemer N, Issa L, Hauck SC, Mani S, Ninnemann O, Kaindl AM.. What's the hype about CDK5RAP2? Cell Mol Life Sci 2011; 68:1719-36; PMID:21327915; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-011-0635-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Megraw TL, Sharkey JT, Nowakowski RS.. Cdk5rap2 exposes the centrosomal root of microcephaly syndromes. Trends Cell Biol 2011; 21:470-80; PMID:21632253; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barker JE, Bernstein SE.. Hertwig's anemia: characterization of the stem cell defect. Blood 1983; 61:765-9; PMID:6831040 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell ES, McFarland EC, Peters H.. Gametic and pleiotropic defects in mouse fetuses with Hertwig's macrocytic anemia. Dev Biol 1985; 110:331-7; PMID:4018402; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90092-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visan A, Hayess K, Sittner D, Pohl EE, Riebeling C, Slawik B, Gulich K, Oelgeschläger M, Luch A, Seiler AE.. Neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells as a tool to assess developmental neurotoxicity in vitro. Neurotoxicology 2012; 33:1135-46; PMID:22732190; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abranches E, Silva M, Pradier L, Schulz H, Hummel O, Henrique D, Bekman E.. Neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells in vitro: a road map to neurogenesis in the embryo. PLoS One 2009; 4:e6286; PMID:19621087; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0006286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ying QL, Stavridis M, Griffiths D, Li M, Smith A.. Conversion of embryonic stem cells into neuroectodermal precursors in adherent monoculture. Nat Biotechnol 2003; 21:183-6; PMID:12524553; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nbt780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z, Wu T, Shi L, Zhang L, Zheng W, Qu JY, Niu R, Qi RZ.. A conserved motif of CDK5RAP2 mediates its localization to centrosomes and the Golgi complex. J Biol Chem 2010; 285(29):22658-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Issa L, Kraemer N, Rickert CH, Sifringer M, Ninnemann O, Stoltenburg-Didinger G, Kaindl AM.. CDK5RAP2 Expression During Murine and Human Brain Development Correlates with Pathology in Primary Autosomal Recessive Microcephaly. Cereb Cortex 2013; 23:2245-60; PMID:22806269; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/cercor/bhs212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucocq JM, Warren G.. Fragmentation and partitioning of the Golgi apparatus during mitosis in HeLa cells. EMBO J 1987; 6:3239-46; PMID:3428259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbins E, Gonatas NK.. The Ultrastructure of a Mammalian Cell during the Mitotic Cycle. J Cell Biol 1964; 21:429-63; PMID:14189913; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.21.3.429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chae HJ, Kang JS, Byun JO, Han KS, Kim DU, Oh SM, Kim HM, Chae SW, Kim HR.. Molecular mechanism of staurosporine-induced apoptosis in osteoblasts. Pharmacol Res 2000; 42:373-81; PMID:10987998; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/phrs.2000.0700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng G, Kaplowitz N.. Mechanism of staurosporine-induced apoptosis in murine hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2002; 282:G825-34; PMID:11960779; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpgi.00467.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seiler AE, Spielmann H.. The validated embryonic stem cell test to predict embryotoxicity in vitro. Nat Protoc 2011; 6:961-78; PMID:21720311; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nprot.2011.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maltsev VA, Rohwedel J, Hescheler J, Wobus AM.. Embryonic stem cells differentiate in vitro into cardiomyocytes representing sinusnodal, atrial and ventricular cell types. Mech Dev 1993; 44:41-50; PMID:8155574; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90015-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sachinidis A, Fleischmann BK, Kolossov E, Wartenberg M, Sauer H, Hescheler J.. Cardiac specific differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Cardiovasc Res 2003; 58:278-91; PMID:12757863; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0008-6363(03)00248-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wobus AM, Wallukat G, Hescheler J.. Pluripotent mouse embryonic stem cells are able to differentiate into cardiomyocytes expressing chronotropic responses to adrenergic and cholinergic agents and Ca2+ channel blockers. Differentiation 1991; 48:173-82; PMID:1725163; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1991.tb00255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banach K, Halbach MD, Hu P, Hescheler J, Egert U.. Development of electrical activity in cardiac myocyte aggregates derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003; 284:H2114-23; PMID:12573993; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpheart.01106.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fong KW, Choi YK, Rattner JB, Qi RZ.. CDK5RAP2 is a pericentriolar protein that functions in centrosomal attachment of the gamma-tubulin ring complex. Mol Biol Cell 2008; 19:115-25; PMID:17959831; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E07-04-0371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S, Rhee K.. CEP215 is involved in the dynein-dependent accumulation of pericentriolar matrix proteins for spindle pole formation. Cell Cycle 2010; 9:774-83; PMID:20139723 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haren L, Stearns T, Luders J.. Plk1-dependent recruitment of gamma-tubulin complexes to mitotic centrosomes involves multiple PCM components. PLoS One 2009; 4:e5976; PMID:19543530; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0005976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Liu D, Lv S, Wang H, Zhong X, Liu B, Wang B, Liao J, Li J, Pfeifer GP, et al.. CDK5RAP2 is required for spindle checkpoint function. Cell Cycle 2009; 8:1206-16; PMID:19282672; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.8.8.8205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim S, Rhee K.. Importance of the CEP215-pericentrin interaction for centrosome maturation during mitosis. PLoS One 2014; 9:e87016; PMID:24466316; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0087016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manning JA, Colussi PA, Koblar SA, Kumar S.. Nedd1 expression as a marker of dynamic centrosomal localization during mouse embryonic development. Histochem Cell Biol 2008; 129:751-64; PMID:18239929; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00418-008-0392-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shitamukai A, Matsuzaki F.. Control of asymmetric cell division of mammalian neural progenitors. Dev Growth Differ 2012; 54:277-86; PMID:22524601; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2012.01345.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie Z, Moy LY, Sanada K, Zhou Y, Buchman JJ, Tsai LH.. Cep120 and TACCs control interkinetic nuclear migration and the neural progenitor pool. Neuron 2007; 56:79-93; PMID:17920017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taverna E, Huttner WB.. Neural progenitor nuclei IN motion. Neuron 2010; 67:906-14; PMID:20869589; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiner O, Sapir T.. Polarity regulation in migrating neurons in the cortex. Mol Neurobiol 2009; 40:1-14; PMID:19330467; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12035-009-8065-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Anda FC, Pollarolo G, Da Silva JS, Camoletto PG, Feiguin F, Dotti CG.. Centrosome localization determines neuronal polarity. Nature 2005; 436:704-8; PMID:16079847; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature03811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ching YP, Qi Z, Wang JH.. Cloning of three novel neuronal Cdk5 activator binding proteins. Gene 2000; 242:285-94; PMID:10721722; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00499-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith AG, Heath JK, Donaldson DD, Wong GG, Moreau J, Stahl M, Rogers D.. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature 1988; 336:688-90; PMID:3143917; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/336688a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams RL, Hilton DJ, Pease S, Willson TA, Stewart CL, Gearing DP, Wagner EF, Metcalf D, Nicola NA, Gough NM.. Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature 1988; 336:684-7; PMID:3143916; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/336684a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraemer N, Neubert G, Issa L, Ninnemann O, Seiler AE, Kaindl AM.. Reference genes in the developing murine brain and in differentiating embryonic stem cells. Neurol Res 2012; 34:664-8; PMID:22735032; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1179/1743132812Y.0000000060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]