Abstract

Holistic processing is a hallmark of face processing. There is evidence that holistic processing is strongest for faces at identification distance, 2 – 10 meters from the observer. However, this evidence is based on tasks that have been little used in the literature and that are indirect measures of holistic processing. We use the composite task– a well validated and frequently used paradigm – to measure the effect of viewing distance on holistic processing. In line with previous work, we find a congruency x alignment effect that is strongest for faces that are close (2m equivalent distance) than for faces that are further away (24m equivalent distance). In contrast, the alignment effect for same trials, used by several authors to measure holistic processing, produced results that are difficult to interpret. We conclude that our results converge with previous findings providing more direct evidence for an effect of size on holistic processing.

Keywords: Holistic Processing, Face Recognition, Complete Design, Composite Task

Introduction

Faces are a rich source of social information. At little more than a glance we can make judgments about a person's identity, emotional state, race, age and sex. No single facial feature contains all of the relevant information for making such judgments. Given this, it is perhaps unsurprising that faces, more than other objects, are processed holistically. For example, Young, Hellawell, and Hay (1987) demonstrated that subjects are slower to identify a face half (e.g., top or bottom) when it is aligned with the complementary half of a different face than when the two halves are misaligned. There is also evidence that holistic processing increases with expertise for non-face object categories, suggesting it may be an important strategy in skilled visual processing more generally (e.g., Boggan, Bartlett & Krawczyk, 2012; Bukach, Phillips, & Gauthier, 2010; Gauthier, Williams, Tarr, & Tanaka, 1998; Wong, Palmeri, Gauthier, 2009).

While holistic processing does not seem to be under voluntary control – that is, participants cannot simply choose to attend to one face part – it can be modulated by stimulus manipulations (e.g. orientation, timing, Rossion & Boremanse, 2009; Richler, Mack et al., 2011) and contextual variables (e.g. background grouping, Curby, Goldstein, & Blacker, 2013). Modulating variables such as these may help elucidate the mechanisms and neural basis of holistic processing, for example evidence of modulation by contextual grouping may implicate mechanisms involved in object-based attention (Curby et al., 2013). Another variable proposed to influence holistic processing is viewing distance (McKone, 2009). Viewing distance is known to disrupt face recognition in general (Loftus & Hartley, 2005), with face recognition ability declining monotonically beyond about 8 meters but remaining good at very close viewing distances. In the only study to date that has looked at the role of viewing distance on holistic processing, McKone (2009) measured the strength of holistic processing for faces at a broad range of viewing distances, ranging from 0.62 meters to 25.96 meters, changing both the distance between the participant and face image and (due to practical limitations) the size of the face image (to simulate viewing distance).

Unlike face recognition ability which appears to be unaffected by very close viewing distances (Loftus & Hartley, 2005), McKone (2009) found that holistic processing declined sharply at viewing distances of less than 2 meters. In addition, as viewing distance increased beyond about 10 meters, faces were processed less holistically. This second finding is perhaps the most surprising since it would seem easier to integrate across parts (or alternatively, harder to focus on a part) when a face is further away. One might expect that faces viewed at a greater distance would actually be more likely treated as an undifferentiated whole, given that there is less fine-grained information available (Loftus & Hartley, 2005) and more of the low spatial frequency information that some authors have suggested may drive holistic processing (Goffaux & Rossion, 2006). While there are many situations in which faces may be encountered at distances closer than 2 meters, these distances are unlikely to correspond to the distance at which people need to be recognized (they are more likely to be conversational distances with people that have already been identified). Likewise, as viewing distance is increased there could be other cues such as body shape or gait that are more important than face recognition for identification. The finding that holistic processing is strongest at distances at which face identification is generally performed (2 – 10 meters) suggests that holistic processing may be a strategy triggered by certain aspects of the stimulus (Jacoby et al., 2003; Bugg & Crump, 2012; Chua, Richler & Gauthier, 2014; submitted).

We revisit the effect of size on holistic processing because it is not clear how the measures of holistic processing used by McKone (2009) relate to more common and more direct ways to measure this construct. “Holistic processing” is used to refer to a host of phenomena that could reflect multiple mechanisms. The heterogeneity in methods used to measure this construct is problematic because there is little evidence that these different measures are related (e.g., Rossion, 2013 vs. Richler & Gauthier, 2013). Evidence for common constructs would typically come from correlational evidence, but because the majority of tasks in this area were not created to measure individual differences, their reliability is too low to observe anything but low correlations with one another (Ross et al., 2014; DeGutis et al, 2013). When reliability is low, a low correlation is difficult to interpret as it can simply reflect a limitation of measurements. For this reason, it is difficult to infer whether McKone's (2009) results would generalize to other measures of holistic processing. The two tasks used by McKone to measure holistic processing are a contrast-matching task (Martini, McKone, & Nakayama, 2006) and a Mooney face task (McKone, 2004). In the contrast matching task participants are shown two faces superimposed upon each other, one face is upright and the other one is inverted. The participant is then asked to adjust the contrast ratio of the two faces until they find the point of subjective equality. In general, the point of subjective equality will be found when the contrast of the inverted face is higher than that of the upright face. A higher contrast for the inverted face is taken to indicate more holistic processing. In the second task participants are shown a particularly hard to see Mooney face and asked, “how 3-dimensional does the face look?” on a 1-9 scale, with a higher rating (more three dimensional) taken to indicate more holistic processing. While these tasks do have some face validity, it is difficult to know how they relate to other more common measures of holistic processing.

The contrast-matching and Mooney tasks are also indirect measures of holistic processing, in that their relation to holistic processing largely rests on evidence that they show an inversion effect (Martini et al., 2006; McKone, 2004). In the contrast-matching task, the ratio of subjective equality is lowest (i.e. the upright face is at a lower contrast threshold than the inverted face) when the orientations are 180° apart and in the Mooney face task, the rated 3-dimensionality of the face is reduced as the face is rotated away from upright. There is strong evidence that inversion disrupts normal face recognition (see McKone & Yovel, 2009 and Rossion, 2008 for a review). It is doubtful however that this disruption can be solely attributed to a disruption of holistic processing. There is evidence for inversion effects in novel objects (e.g., Ashworth III, Vuong, Rossion, & Tarr, 2008). While there is a general consensus in the literature that holistic processing is reduced or abolished by inversion (e.g. Van Belle, De Graef, Verfaillie, Rossion, Lefèvre, 2010; Young et al., 1987; Richler, Mack et al., 2011), it does not follow that every inversion effect is explained by holistic processing (a point made before by other authors, Valentine, 1988; Robbins & McKone, 2006). Thus, while inversion often disrupts holistic processing, it is not a direct measure of this construct.

In this paper, we aimed to investigate the effect of viewing distance using a more direct measure of holistic processing, namely the composite task. In the composite task, participants must indicate whether the cued half, top or bottom, of a test face is the same as, or different from a study face. As in the classic demonstration by Young et al. (1987), a study face composed of two face halves is shown, followed by a blank screen or mask, and then a test face. Participants must then indicate by button press whether the cued half of the test face is the same as, or different from the study face. The task provides a fairly direct measure of holistic processing - if participants cannot inhibit a holistic strategy for processing the faces, their decision (same or different) will be influenced to some extent by the supposedly ignored half. Exactly how holistic processing is operationalized depends on the version of the composite task being used. In one version of the task, the to-be-ignored half is always different while the cued half of the study and test faces can be either the same or different. Holistic processing is operationalized as an alignment effect, with accuracy generally found to be lower on aligned-same trials compared to misaligned-same trials (e.g., Goffaux & Rossion, 2006). The other version of this task is an extended version of this design, often referred to as the ”complete” design, that includes the complementary trials in which the to-be-ignored half is the same across study and test (Gauthier & Bukach, 2007). When all trials are included, it is possible to calculate in addition to the alignment effect on the trials where the irrelevant part is different, a congruency x alignment interaction that is an alternative measure of holistic processing. On congruent trials, a failure to selectively attend to the cued part should facilitate performance, whereas, on incongruent trials, a failure to selectively attend to the cued part should hinder performance. This difference in performance between congruent and incongruent trials is reduced on misaligned trials (e.g., De Gutis, Wilmer, Mercado, & Cohan, 2013; Richler, Cheung, & Gauthier, 2011a; Richler, Tanaka, Brown, Gauthier, 2008).

While the composite task may be the current measure of choice for holistic processing, there is ample coverage of the ongoing debate surrounding two versions of the task. An entire issue of this Journal was devoted to a review of work based on the alignment effect and a critique of the extended design (Rossion 2013), with counter arguments (Richler & Gauthier, 2013). A recent meta-analysis of holistic processing compared the two versions of the task (Richler & Gauthier, 2014). While the extended design doubles the number of trials relative to the version with only different irrelevant trials, it produces an effect size that is about three times as large (Richler & Gauthier, 2014). When they have been compared in the same dataset, the two measures often do not lead to the same conclusions (Richler et al., 2012; Richler, Cheung, & Gauthier, 2011b). In the complete design, holistic processing can technically be evidenced by the presence of a congruency effect, because such an effect demonstrates that subjects are unable to ignore the task-irrelevant part. However, it is standard in group studies to use the interaction between congruency and alignment, as misalignment greatly reduces the congruency effect (Richler & Gauthier, 2014). The main advantage of the congruency x alignment effect over the alignment effect is robustness to manipulations that influence a particular response bias associated with alignment and congruency (as reviewed by Richler & Gauthier, 2014; see Meinhardt et al., 2014 for the same conclusion). In theory, both measures may tap into the same failures of selective attention in aligned faces, but the two effects show little relation across studies (r = .27, p=.18; Richler & Gauthier, 2014).

In this context, we decided to explore the role of size on holistic processing as measured by the composite task. Our primary measure will be the congruency x alignment effect, but by using the extended design, we can also calculate the alignment effect on trials where the irrelevant part is different. Richler et al. (2011) demonstrated that the standard alignment effect can be obtained in the context of the other trials. But it is possible that the alignment effect is influenced by such context, in line with evidence that the effect is sensitive to manipulations that influence response bias (Richler et al., 2011). Relevant to a size manipulation, the alignment effect has been found to be sensitive to spatial frequency (Goffaux, Hault, Michel, Vuong, & Rossion, 2005; Goffaux & Rossion, 2006), but there is evidence that this is mediated by response bias (Cheung, Richler, Palmeri, & Gauthier, 2008). This could be problematic in the current study given that viewing distance is known to change the relative contribution of low and high spatial frequency information (Loftus & Harley, 2005). Therefore, the alignment x congruency effect, which was not influenced by spatial frequency (Cheung, Richler, Palmeri, & Gauthier, 2008) provides a relatively stronger test of whether size itself influences holistic processing.

McKone (2009) noted the Mooney face and contrast matching tasks have the advantage over the composite task that they do not require participants to judge identity. This could be problematic because viewing distance affects identification accuracy, (although it depends more on cycles per face then on cycles per degree of visual angle (Liu et al., 2000). There is a possible confound with the composite measure of holistic processing because it relies on identifying face parts. However, given that holistic processing in the composite task is indexed by an interaction, it is not necessarily the case that as face recognition decreases, so must holistic processing (assuming that there are no floor or ceiling effects).

Given the practical limitations of large distance manipulations from the monitor, we opted to maintain a constant viewing distance from the monitor and to only manipulate image size. This was sufficient to test for the effect of size equivalent to distances spanning a range of 2 to 24 meters from the observer. Relative to a direct manipulation of distance, manipulating image size provides an equivalency in terms of the stimulus information available to the observer.

Method

Participants

One hundred and one volunteers were recruited from the Vanderbilt University participant panel (30 males, mean age 20.7 years, SD = 3.7). A sample size of 100 was pre-determined (one more subject was included by mistake) based on other work that looked at interactions between holistic processing in the extended design and other conditions (Chua, Richler & Gauthier, 2014). The effect size for holistic processing in the extended design is relatively large (meta-analysis of 48 independent datasets, N=1545, ηP2 = .32, 95% CI: .28, .35), such 95% power can be achieved with only 14 participants (at an alpha of .05). But its reliability is often low (DeGutis et al., 2013; Ross, Richler, & Gauthier, in press), such that larger sample sizes are required to test for interactions using this task, even in within-subjects designs. Subjects took part either for course credit or monetary compensation.

Stimuli

Thirty-six face images were drawn from the PUT Face Database (Kasiński, Florek, & Schmidt, 2008). All images were high-resolution, frontal views with the external features cropped removing the hair and ears but preserving the jaw line. The stimuli were converted to grayscale and cut in half to produce top and bottom face parts. The face parts were arbitrarily assigned to one of four sets, with the condition that the top and bottom parts from any given face were never paired in a set. Composite faces, used in each trial of the experiment, were constructed by randomly recombining the top and bottom parts within a given set and presenting them on a grey background separated by a white line. Misaligned stimuli were created by horizontally offsetting the top and bottom half such that the edge of one half fell approximately in the center of the other half. The composites in each set were rescaled to four different sizes 25.31, 8.44, 3.37, 2.11 cm, corresponding to 4.14, 1.38, 0.55 and 0.35 degrees of vertical visual angle respectively (viewed from 350cm). These visual angles were chosen, based on an average estimated head size of 14.46 cm (McKone, 2009), to span a broad range of natural viewing distances, namely, 200, 600, 1500 and 2400 cm between the viewer and the target. A visual pattern mask, created using the “tiny lens” filter in Photoshop, which has been used in several previous studies (e.g., Richler, Mack, Palmeri & Gauthier. 2011) was also used here.

Procedure

Subjects were seated in a dimly lit room and their head position was stabilized with a headrest at a distance of 350 cm from the monitor. Each subject completed four blocks, with each block containing 160 trials of faces at one size and from one set. Across participants the block order of face sets was kept constant and only the block order of face size was counterbalanced. On each trial, a fixation cross was presented for 200ms, followed by a study face for 200ms and then a visual pattern mask for 500ms. Next, a test face was presented for 200ms followed by a blank response screen that remained for 4800ms before moving on to the next trial. Timeouts were extremely rare (<1% of trials) and these trials were excluded from analyses. In all cases, subjects were instructed to respond by key press if the top part of the test face matched the top part of the study face. At the beginning of each block there was a 16-trial practice block to acquaint the subject with the stimuli.

Results

Congruency x alignment effect

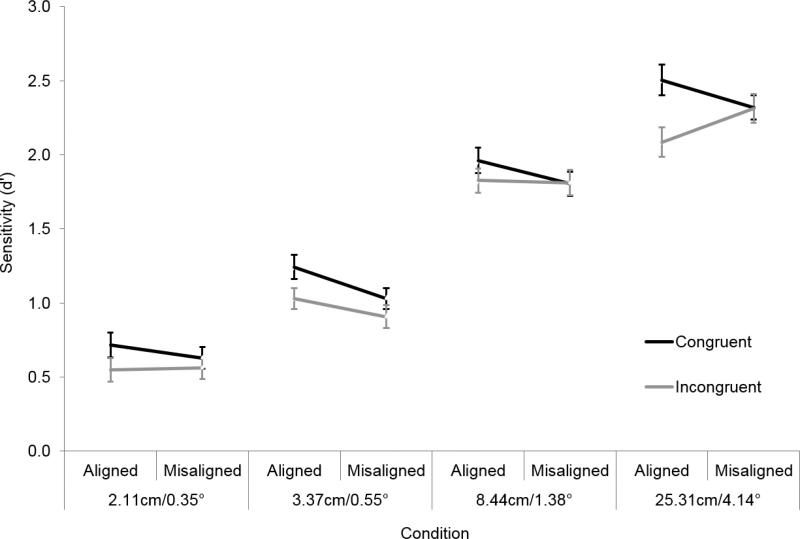

Two subjects were excluded from the analysis because they did not perform above chance across when the accuracy was combined across all the blocks. For each block the same/different accuracy scores for each of the four conditions (congruent aligned, congruent misaligned, incongruent aligned and incongruent misaligned) were converted to sensitivity, d’ (see Figure 1.). A 3 factors ANOVA (alignment, congruency and a linear contrast) revealed a significant main effect of alignment, F(1, 98) = 5.86, MSE = 1.61, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.06, and congruency, F(1, 98) = 52.76, MSE = 12.19, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.35, as well as a significant interaction, F(1, 98) = 17.10, MSE = 3.76, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.15. In addition, a linear trend analysis revealed a significant three-way interaction between alignment, congruency and composite size (using linear contrast weights), F(1, 98) = 4.36, MSE = 1.34, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.04. The magnitude of holistic processing varied from virtually none at the smallest size we used (visual angle = 0.35°; ηp2= .000; p=.77) to much more sizeable holistic processing at the largest size we used (visual angle = 4.14°; ηp2= .09; p=.003). As would be expected, the interaction of congruency with size was entirely driven by the aligned condition (ηp2= .05; p=.03) and was not observed in the misaligned condition (ηp2= .005; p=.47)1. While the accuracy is clearly lower in the smallest composite condition, participants were still well above chance in matching the face halves. Finally, although this was not the focus of our analyses, the correlation between the congruency x alignment for each participant across the different sizes is extremely low, with the average correlation between pairs of conditions essentially zero, r = -0.02. This is consistent with the fact that this version of the composite task, while highly sensitive at the group level, is generally not sufficiently reliable for individual differences analyses (Ross, Richler & Gauthier, 2014; Richler & Gauthier, 2014)

Figure 1.

Sensitivity d’ on congruent and incongruent trials as a function of alignment (aligned/misaligned) face size (cm)/visual angle (degrees). Error bars are 95% within-subjects confidence intervals.

Alignment effect on trials with different irrelevant parts

We also calculated the alignment effect as measured in prior work, based on the hit rate on trials where the irrelevant part is different (see Rossion, 2013). The alignment effect thus refers to performance on same misaligned trials – performance on same aligned trials. A linear trend analysis revealed a significant two-way interaction between alignment and image size (using linear contrast weights), F(1, 98) = 9.25, MSE = .1013, p=.003, ηp2 = .04. The direction of the linear trend for this alignment effect is the same as for the alignment x congruency effect, however unlike in that analysis there was no holistic processing for the two largest sizes (t(98) = 0.62, d = .06, p = .54 and t(98) = 1.27, d = .13, p = .21 respectively) suggesting that the effect was driven by a negative alignment effect (more accuracy for same aligned trials than same misaligned trials) for the two smallest sizes (t(98) = -2.20, d = -.22, p = .03 and t(98) = -2.85, -d = .29, p = .005 respectively). As in prior work (e.g., Harrison et al., 2014), the alignment effect correlated with the bias measure from the extended design (the alignment x congruency response bias) in all conditions (r = .39, r = .40, r = .34, r = .39 from the smallest to the largest face size).

Discussion

Previous work suggested that faces are processed less holistically outside of distances relevant to individuation, approximately 2 – 10m (McKone, 2009). One limitation of this previous research is that it inferred the degree of holistic processing from tasks that have not been standards in the measurement of holistic processing. Here, we extended these findings, using the composite task, which has been more widely used as a measure of holistic processing (e.g. Cheung et al, 2008; Curby et al., 2013; De Gutis et al, 2013; Gao et al, 2011; Meinhardt et al., 2014; Rossion, 2013; Zhou et al., 2012). In line with McKone (2009), we found that the magnitude of holistic processing was lower as faces were made smaller (i.e. further away), with no holistic processing for faces that were simulated to be 24m away. The fact that the results with the congruency x alignment effect, a measure of holistic processing with proven validity and sensitivity (Richler & Gauthier, 2014), align with those of McKone (2009) provides strong evidence that holistic processing is sensitive to viewing distance.

In contrast, a different measure, the alignment effect (Rossion, 2013), produced a different pattern. We did find a linear trend whereby the alignment effect was larger for the larger faces. However, the effect was driven by a negative alignment effect for the smallest two sizes of faces, rather than a positive alignment effect for the largest two sizes of faces. This negative alignment effect is both difficult to interpret and difficult to reconcile with the literature, given that our largest face size is similar to the face size used in most face recognition research. Consistent with prior work we found that the partial design measure across subjects was correlated with the alignment x congruency response bias, which may explain the aberrant pattern of results. Although congruency is not a factor of interest in the partial design, its influence on response bias cannot be factored out. Subjects perform a same/different task that is fully confounded with congruency, and performance on same trials can be influenced in two ways: 1) alignment can make the task harder on same trials and 2) alignment can affect the response bias associated with congruency. The two influences may operate to different extent for different subjects and cannot be distinguished without the complementary trials. In the present study, despite a very large sample size relative to prior work, the alignment effect did not capture normal holistic processing even at standard experimental sizes. The effect size for the alignment effect is smaller than it was in a recent analysis where publication bias was not a concern, because it was computed on a set of studies in which this particular effect was not the effect of interest (Richler & Gauthier, 2014). Publication bias is of course always a possible explanation when an effect does not replicate (Rosenthal, 1979). Also, note that because they care mostly about same trials, researchers measuring the alignment effect often include a larger proportion of same trials (Rossion, 2013), but this influences response bias (Richler et al., 2012) and therefore may have inflated prior estimates. It is also possible to argue that the alignment effect cannot be measured in the context of trials where the irrelevant part is the same, but there is no theoretical reason why this should be and would suggest an effect that is highly sensitive to context. In which case, it would not be advisable to use a measure in which potentially influential response biases cannot be measured.

Considerable evidence shows that under most circumstances holistic processing is automatically engaged when a face is encountered. Indeed, the logic of the composite task is that subjects are unable to selectively attend to just one part of the face. It is interesting to speculate about the specific factors that might reduce holistic processing outside of the 2 – 10 meter viewing range. At all viewing distances, the image can clearly be categorized as a face, though identifying information is very limited at the furthest distance. It may be that the limited range of spatial frequency information available causes the reduction in holistic processing at the furthest distances. However, by this account, spatial frequency filtering should also significantly reduce, or abolish, holistic processing and this was not found in prior work with the congruency x alignment effect (Cheung et al., 2008). An alternative is that a general reduction in available information was sufficient to bring about a change in strategy – viewing conditions may be sufficiently different not to trigger holistic processing. This would be consistent with the idea that holistic processing is a learned attention phenomenon (Chua et al., 2014; Chua et al., submitted).

As we pointed out in the introduction, the aim of this paper was to complement the measures of holistic processing used by McKone (2009). There are at least a dozen measures of holistic processing (Richler, Palmeri, & Gauthier, 2012). The task we chose is of particular theoretical interest because it has been shown to be a hallmark of face recognition relative to objects in novices (e.g. Wong et al., 2009). Moreover, it is sensitive to visual expertise with other categories of object (Wong et al., 2009; Bukach et al., 2010). The convergence of our results with the two measures used by McKone (2009) suggest that the three tasks may tap into the same construct, but an individual differences approach would be better suited to answer this questions.

One potential limitation of our study is that we chose to focus on what happens to holistic processing at a sizes that were equivalent to viewing distances of 2 meters or further, whereas McKone (2009) also looked both at closer viewing conditions. Our decision was based on the intuition that, to the extent that spatial attention can be directed away from the irrelevant part of the face by moving one's eyes (i.e. in the case that the participants field of vision is not sufficient to capture the whole face), a failure of selective attention is less likely to be observed. Thus, it is unclear that the composite task would be a valid measure of holistic processing at closer distances. Arguably, it would be possible to test somewhat closer than we did, though based on the current results we have no reason to suspect that the findings would be different to those reported by McKone (2009).

Overall, the findings presented here are in line with previous work and indicate that faces are processed most holistically in the range of 2 – 10 meters, a range of distances that corresponds to the typical distance at which facial information is used for identification (McKone, 2009). While both the “partial” and “complete” design measures of holistic processing show broadly similar patterns of results, the finding of a negative alignment effect using the partial design trials highlights the fact that not all measures of holistic processing can be assumed to measure the same thing.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NSF (Grant SBE-0542013), VVRC (Grant P30-EY008126) and NEI (Grant R01 EY013441-06A2). We thank Riaun Floyd for help with data collection.

Footnotes

Inspection of the RTs did not reveal any evidence of a speed accuracy trade off. Mean RTs were positively correlated with errors across conditions, r = 0.96. A 3 factors ANOVA (alignment, congruency and a linear contrast) revealed a significant main effect of alignment, F(1, 98) = 7.88, MSE = 31124, p < 0.05, but no effect of congruency, F(1, 98) = 1.68, MSE = 7740, p < 0.05 and a marginal interaction, F(1, 98) = 3.21, MSE = 9276, p < 0.05 but the a linear trend analysis did not show a significant three-way interaction, F(1, 98) = 0.73, MSE = 3833, p > 0.05.

References

- Ashworth ARS, Vuong QC, Rossion B, Tarr MJ. Recognizing rotated faces and Greebles: What properties drive the face inversion effect? Visual Cognition. 2008;16(6):754–784. [Google Scholar]

- Boggan AL, Bartlett JC, Krawczyk DC. Chess masters show a hallmark of face processing with chess. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2012;141(1):37–42. doi: 10.1037/a0024236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukach CM, Phillips SW, Gauthier I. Limits of generalization between categories and implications for theories of category specificity. Attention, Perception and Psychophysics. 2010:1865–1874. doi: 10.3758/APP.72.7.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civile C, McLaren RP, McLaren IP. The face inversion effect – Parts and wholes: Individual features and their configuration. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2013.828315. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung OS, Richler JJ, Palmeri TJ, Gauthier I. Revisiting the role of spatial frequencies in the holistic processing of faces. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2008;34(6):1327–1336. doi: 10.1037/a0011752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua K-W, Richler JJ, Gauthier I. Becoming a Lunari or Taiyo expert: Learned attention to parts drives holistic processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2014;40(3):1174–1182. doi: 10.1037/a0035895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curby KM, Goldstein RR, Blacker K. Disrupting perceptual grouping of face parts impairs holistic face processing. Attention, Perception and Psychophysics. 2013;75(1):83–91. doi: 10.3758/s13414-012-0386-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGutis J, Wilmer J, Mercado RJ, Cohan S. Using regression to measure holistic face processing reveals a strong link with face recognition ability. Cognition. 2013;126:87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Flevaris AV, Robertson LC, Bentin S. Priming global and local processing of composite faces: Revisiting the processing-bias effect on face perception. Attention, Perception and Psychophysics. 2011;73:1477–1486. doi: 10.3758/s13414-011-0109-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier I, Bukach C. Should we reject the expertise hypothesis? Cognition. 2007;103:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier I, Williams P, Tarr MJ, Tanaka J. Training “Greeble” experts: A framework for studying expert object recognition processes. Vision Research. 1998;38:2401–2428. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffaux V, Hault B, Michel C, Vuong QC, Rossion B. The respective role of low and high spatial frequencies in supporting configural and featural processing of faces. Perception. 2005;34:77–86. doi: 10.1068/p5370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffaux V, Rossion B. Faces are “spatial” – Holistic face perception is supported by low spatial frequencies. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2006;32:1023–1039. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.32.4.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SA, Gauthier I, Hayward WG, Richler JJ. Other-race effects manifest in overall performance, not qualitative processing style. Visual Cognition. 2014;22(6):843–864. [Google Scholar]

- Kasińsky A, Florek A, Schmidt A. The PUT face database. Image Processing & Communication. 2008;3:59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Loftus GR, Harley EM. Why is it easier to identify someone close than far away? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2005;12(1):43–65. doi: 10.3758/bf03196348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini P, McKone E, Nakayama K. Orientation tuning of human face processing estimated by contrast matching in transparency displays. Vision Research. 2006;46(13):2102–2109. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKone E. Isolating the special component of face recognition: Peripheral identification and a Mooney face. 2004;30:181–197. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.30.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKone E. Holistic processing for faces operates over a wide range of sizes but is strongest at identification rather than conversational distances. Vision Research. 2009;49(2):268–283. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKone E, Yovel G. Why does picture-plane inversion sometimes dissociate perception of features and spacing in faces, and sometimes not? Psychonomics Bulletin and Review. 2009;16(5):778–797. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.5.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt G, Meinhardt-Injac B, Persike M. The complete design in the composite face paradigm: role of response bias, target certainty, and feedback. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014;31 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00885. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler JJ, Cheung OS, Gauthier I. Holistic processing predicts face recognition. Psychological Science. 2011a;24(4):17, 464–471. doi: 10.1177/0956797611401753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler JJ, Cheung OS, Gauthier I. Beliefs alter holistic face processing... if response bias is not taken into account. Journal of Vision. 2011b;11(13):17, 1–13. doi: 10.1167/11.13.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler JJ, Gauthier I. A meta-analysis and review of holistic face processing. Psychological Bulletin. doi: 10.1037/a0037004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler JJ, Mack ML, Palmeri TJ, Gauthier I. Inverted faces are (eventually) processed holistically. Vision Research. 2011;51(3):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler JJ, Palmeri TJ, Gauthier I. Meanings, mechanisms, and measures of holistic processing. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler JJ, Tanaka JW, Brown DD, Gauthier I. Why does selective attention fail in face processing? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2008;34(6):1356–1368. doi: 10.1037/a0013080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler JJ, Wong YK, Gauthier I. Perceptual expertise as a shift from strategic interference to automatic holistic processing. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20(2):129–134. doi: 10.1177/0963721411402472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins R, McKone E. No face-like processing for objects-of-expertise in three behavioral tasks. Cognition. 2006;103(1):34–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. The “file drawer problem” and tolerance for null results. Psychological bulletin. 1979;86:638–641. [Google Scholar]

- Ross DA, Richler JJ, Gauthier I. Reliability of composite task measurements of holistic processing. Behavior Research Methods. doi: 10.3758/s13428-014-0497-4. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B. Picture-plane inversion leads to qualitative changes of face perception. Acta Psychologica. 2008;128:274–289. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B, Boremanse A. Nonlinear relationship between holistic processing of individual faces and picture-plane rotation: Evidence from the face composite illusion. Journal of Vision. 2009;8(4):1–13. doi: 10.1167/8.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossion B. The composite face illusion: A whole window into our understanding of holistic face perception. Visual Cognition. 2013;21(2):1–115. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine T. Upside-down faces: a review of the effect of inversion upon face recognition. British Journal of Psychology. 1988;79:471–491. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1988.tb02747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Belle G, De Graef P, Verfaillie K, Rossion B, Lefèvre P. Face inversion impairs holistic perception: evidence from gaze-contingent stimulation. Journal of Vision. 2010;10(5):10. doi: 10.1167/10.5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AC-N, Palmeri TJ, Gauthier I. Conditions for face-like expertise with objects: Becoming a Ziggerin expert – but which type? Psychological Science. 2009;20(9):1108–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AW, Hellawell D, Hay DC. Configurational information in face perception. Perception. 1987;16:747–759. doi: 10.1068/p160747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Cheng Z, Zhang X, Wong ACN. Smaller holistic processing of faces associated with face drawing experience. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2012;19(2):157–162. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]