Our results indicate that multidetector CT regional strain analysis has the potential to detect abnormalities in myocardial function in cardiomyopathy in a manner similar to cardiac MR strain analysis.

Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the use of cine multidetector computed tomography (CT) to detect changes in myocardial function in a swine cardiomyopathy model.

Materials and Methods

All animal protocols were in accordance with the Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing Research and Training and approved by the University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee. Strain analysis of cine multidetector CT images of the left ventricle was optimized and analyzed with feature-tracking software. The standard of reference for strain was harmonic phase analysis of tagged cardiac magnetic resonance (MR) images at 3.0 T. An animal model of cardiomyopathy was imaged with both cardiac MR and 320-section multidetector CT at a temporal resolution of less than 50 msec. Three groups were evaluated: control group (n = 5), aortic-banded myocardial hypertrophy group (n = 5), and aortic-banded and cyclosporine A– treated cardiomyopathy group (n = 5). Histologic samples of the myocardium were obtained for comparison with strain results. Dunnett test was used for comparisons of the concentric remodeling group and eccentric remodeling group against the control group.

Results

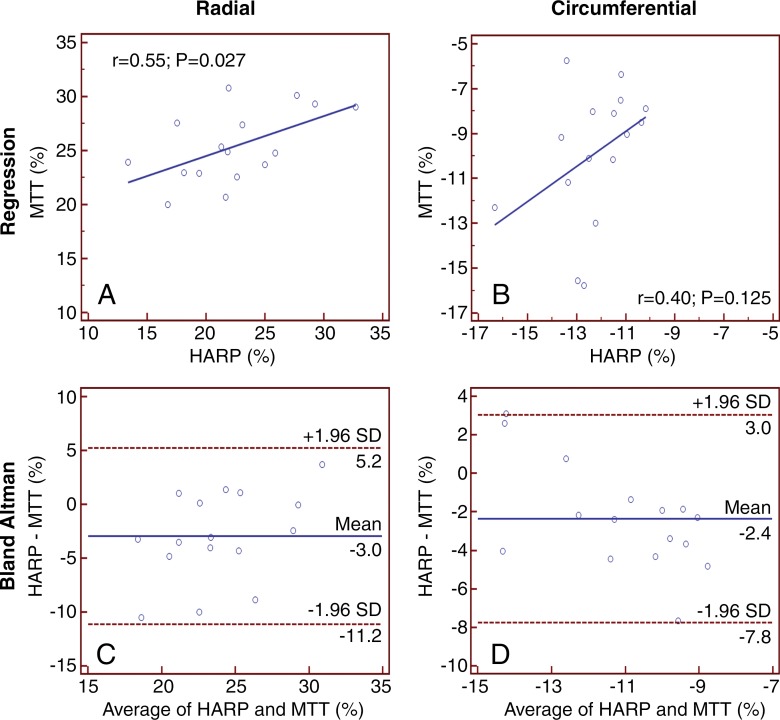

Collagen volume fraction ranged from 10.9% to 14.2%; lower collagen fraction values were seen in the control group than in the cardiomyopathy groups (P < .05). Ejection fraction and conventional metrics showed no significant differences between control and cardiomyopathy groups. Radial strain for both cardiac MR and multidetector CT was abnormal in both concentric (cardiac MR 25.1% ± 4.2; multidetector CT 28.4% ± 2.8) and eccentric (cardiac MR 23.2% ± 2.0; multidetector CT 24.4% ± 2.1) remodeling groups relative to control group (cardiac MR 18.9% ± 1.9, multidetector CT 22.0% ± 1.7, P < .05, all comparisons). Strain values for multidetector CT versus cardiac MR showed better agreement in the radial direction than in the circumferential direction (r = 0.55, P = .03 vs r = 0.40, P = .13, respectively).

Conclusion

Multidetector CT strain analysis has potential to identify regional wall-motion abnormalities in cardiomyopathy that is not otherwise detected using conventional metrics of myocardial function.

© RSNA, 2015

Introduction

Advances in multidetector computed tomography (CT) have resulted in lower radiation dose and higher temporal resolution for imaging of the coronary arteries and myocardium. Multidetector CT has proven to be robust and accurate for detection of coronary artery stenosis (1,2) and has shown high clinical (3) and economical (4) relevance. However, comprehensive evaluation of the myocardium will also need to involve characterization of cardiac function at both a regional and global level.

The reference standard for characterization of cardiac regional function is currently tagged cardiac magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (5). Tagged MR image acquisition and processing for strain analysis remains time consuming and is thus usually not performed for clinical studies. However, regional function analysis of the myocardium with multidetector CT has been shown to identify focal wall-motion abnormalities in a manner analogous to cardiac MR strain (6) due to myocardial infarction (7).

In contrast, a common feature of many nonischemic cardiomyopathies is the development of diffuse interstitial and replacement myocardial fibrosis (8). Depending on the extent of the disease, regional and global motion abnormalities are associated with interstitial fibrosis. Noninvasive detection of myocardial function abnormalities in diffuse disease is challenging and relies on quantitative analysis of myocardial strain. We hypothesized that strain measurements would help detect differences between the cardiomyopathy groups and the control group. The purpose of this study was to investigate the use of cine multidetector CT to detect changes in myocardial function in a swine cardiomyopathy model.

Materials and Methods

Animal Preparation

All animal protocols were in accordance with the Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing Research and Training and approved by the University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee. The animals used in the current study were previously characterized (9,10) in terms of concentric (hypertrophy) and eccentric (dilatation, increased mass) remodeling of the left ventricle (LV). In brief, intact male Yucatan miniature swine (27–30 kg; 8 months old) were matched for body mass and cardiac function. Animals were randomly assigned to control (n = 5), aortic-banded (concentric hypertrophy) group (n = 5), and aortic-banded and cyclosporine A–treated cardiomyopathy (eccentric remodeling, heart failure) group (n = 5). Mild hypertrophy and heart failure was induced with aortic banding for a period of 20 weeks (10,11) by using previously published techniques (11), with in vivo determination of LV and mean arterial pressure prior to humane euthanasia. Cross sections of the LV matched to cardiac MR and multidetector CT short-axis images were formalin fixed, embedded in paraffin, and stained for assessment of fibrosis and collagen as previously described (12).

Cardiac MR Parameters and Analysis

Cardiac MR images were obtained with a 3.0-T imager (Biograph mMR; Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) with a phase-array coil. Grid short-axis tagged cardiac MR images were acquired by using an electrocardiographically triggered fast gradient-echo sequence, with a spatial modulation of magnetization (repetition time msec/echo time msec, 15.5/2.3; flip angle, 10°; field of view, 360 × 400 mm; section thickness, 6 mm; gap, 4 mm; phase resolution, 75%–85%; matrix size, 256 × 256; tag distance, 6 mm; segmentation factor, three; temporal resolution, 16 msec). Tagged images were analyzed by using the reference standard method, harmonic phase-analysis software (HARP, version 4.3.1; Diagnosoft, Morrisville, NC) (13).

Imaging for myocardial scar was performed by using late gadolinium enhancement cardiac MR after intravenous infusion of gadopentetate dimeglumine (0.15 mmol per kilogram of body weight, Magnevist; Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Wayne, NJ) via a 20-gauge peripheral catheter. Phase-sensitive inversion-recovery late gadolinium enhancement cardiac MR imaging was performed 15 minutes after injection.

Multidetector CT Scanning

Multidetector CT images were acquired with an Aquilion 320 One Vision scanner (Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) with echocardiographic monitoring. A 60 mL bolus of nonionic contrast agent iodixanol (Visipaque, 320 mg iodine per milliliter; GE Healthcare, Oslo, Norway) was used at a 5-mL/sec flow rate at a dose of 2 mL/kg, followed by a saline bolus chaser using a double-head power injector. Bolus tracking was performed to yield homogeneous enhancement of the ventricular cavity (14).

Cine cardiac images were acquired with the following parameters: gantry rotation time, 275 msec; tube current, 350–450 mA; tube voltage, 120 kV; collimation, 0.5 mm; isotropic image matrix, 512 × 512 pixels; three to four R-R interval segmented acquisition (average temporal resolution, 49 msec). Multidetector CT images were reconstructed with multiple segment iterative reconstruction algorithms (AIDR3D standard; Toshiba Medical Systems). Twenty images were reconstructed every 5% over the R-R interval.

Images were transferred to a dedicated off-line workstation (Vitrea 2; Vital Images, Minnetonka, Minn). They were reformatted into apical, middle, and basal short-axis views according to the 16-segment model from the American Heart Association classification, with 5-mm section thickness. Window level was adjusted to optimize the contrast between tissue and blood. Cine images were stored in the audio video interleave, or AVI, uncompressed format.

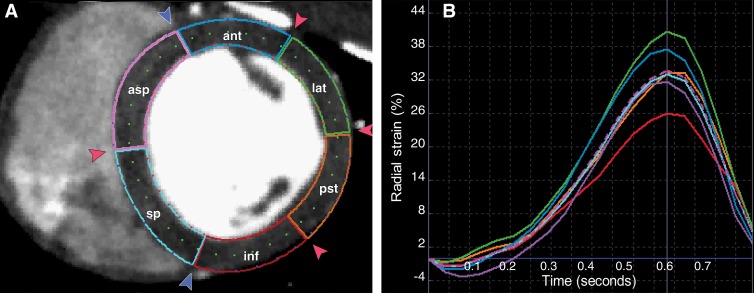

Cine multidetector CT AVI images were uploaded into multimodality tissue-tracking software (Toshiba, v.6.0, Tokyo, Japan) for regional strain calculation (7). Multimodality tissue tracking was used to calculate strain between sequential image frames, from systole to diastole, by using an on-screen pixel pattern template-matching technique adapted from echocardiography (15). After semiautomatic contouring of the endocardial and epicardial borders, multiple tracking points (small pixel patterns representing tissue contours) were identified. Around each tracking point, a template image (10 × 10 mm) was assigned. By searching in the following frame for the most similar template image, the new location of the tracking point was determined. A squared error function was used to test for template similarity. From these correspondences made between frames, motion vectors were created and strain was quantified (Fig 1).

Figure 1:

Multimodality tissue tracking analysis for multidetector CT images. A, American Heart Association segmentation of short axis into anterior (ant), anterior septal (asp), inferior (inf ), lateral (lat), septal (sp), and posterior (pst) segments at the mid LV at end diastole. B, Strain curve of multimodality tissue tracking analysis for multidetector CT images. The y-axis represents percentage of radial strain. The x-axis represents time during the cardiac cycle. Tracing of endocardial and epicardial borders was performed at end diastole (A ).

The inferior and anterior insertion points of the right ventricle on the interventricular septum were used as reference for cardiac segmentation. End systole was determined as the time of aortic valve closure. Segments with inadequate tracking were excluded from strain analysis. After successful tracking, the magnitude and timing of peak systolic radial strain for each of six equiangular segments was extracted and used for further analyses. To compare strain measurements obtained with multidetector CT to those obtained with tagged cardiac MR imaging, multidetector CT data were also grouped according to the American Heart Association 16-segment analysis by using tagged cardiac MR images and anatomic landmarks and intracavitary diameter. Two experienced cardiovascular imaging researchers (M.W.T. and F.S.R., with 8 and 3 years of experience, respectively) evaluated image quality independently.

Statistical Methods

Data are presented as means ± standard error. Dunnett test was used for comparisons of the concentric remodeling group and eccentric remodeling group against control group. Validation comparison of strain values for harmonic phase analysis and multimodality tissue tracking was evaluated by using linear-regression analysis and Bland-Altman plots. Intra- and interobserver variability in multidetector CT strain measurements were evaluated for the midsection by using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in a two-way random model: ICC less than 0.40, poor agreement; ICC of 0.40 to 0.75, good agreement; ICC greater than 0.75, excellent agreement. Significant differences were considered at a P value < .05. Statistical analyses were performed by using MedCalc 12.2.1 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) software.

Results

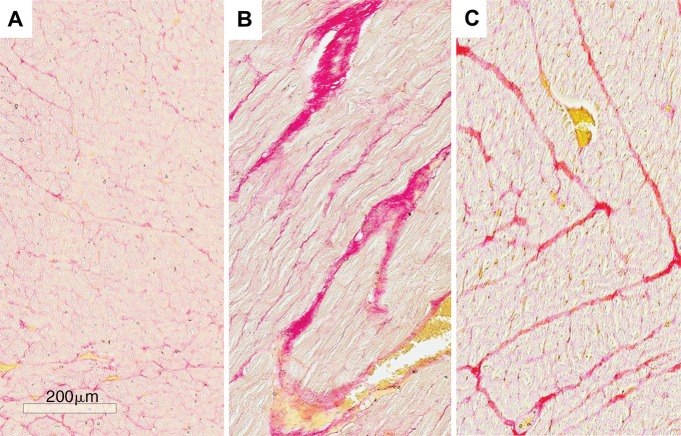

Histologic analysis was performed in 15 animals. Animals in the control group showed evidence of less collagen compared with animals in the concentric and eccentric remodeling groups (Fig 2). Overall, the mean collagen volume fraction was 10.9% in the control group compared with 14.2% and 12.5% in the concentric and eccentric remodeling groups, respectively (P < .05 for both comparisons). No focal scars were detected at late gadolinium enhancement cardiac MR or histologic examination.

Figure 2:

Representative photomicrographs of histologic analysis for collagen staining in, A, control group with 10% collagen volume fraction (CVF ), B, concentric remodeling group with 15% CVF, and, C, eccentric remodeling group with 13% CVF. (Picrosirius red stain; scale bar, 200 μm).

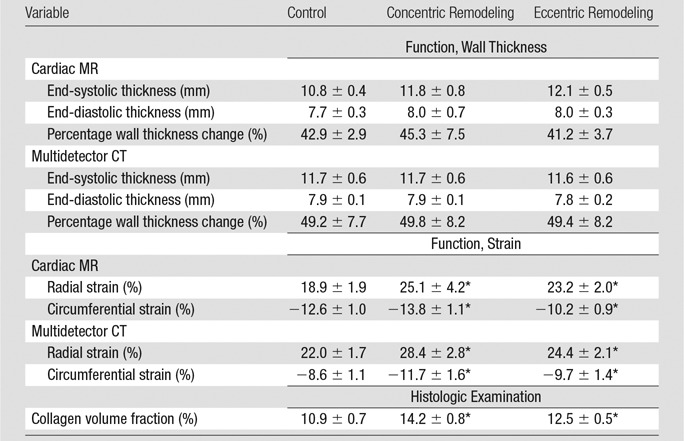

Cardiac MR and multidetector CT imaging examinations were available in 12 of 15 animals (two in control and one in concentric remodeling groups were excluded due to inadequate image quality). This resulted in a total of 192 segments available for function analysis, of which 167 (87%) were analyzable with both cardiac MR imaging and multidetector CT. Global and regional measures of LV structure obtained at multidetector CT, cardiac MR imaging, and histologic examination are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

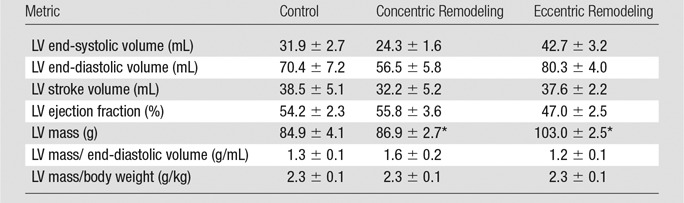

Table 1.

Global Metrics of LV Structure from Multidetector CT

Note.—Data are means ± standard error.

*Significant differences from the control group (P < .05).

Table 2.

Cardiac MR Imaging versus Multidetector CT Regional Function versus Histologic Examination

Note.—Data are means ± standard error.

*Significant differences from the control group (P < .05).

LV mass was greatest in the eccentric remodeling group (103 g) compared with concentric remodeling group (87 g) and control group (85 g) (P < .05 vs control). When adjusted for body weight or end-diastolic volume, LV mass was not significantly different. Conventional function metrics obtained with both multidetector CT and cardiac MR, such as ejection fraction, were lower in the eccentric remodeling group than in the control group but were not statistically significant (eg, ejection fraction, 47% vs 54%, respectively, at multidetector CT, P > .05). Similarly, comparisons between the control group versus cardiomyopathy groups showed no statistically significant group differences in conventional parameters, such as stroke volume, end-diastolic volume, and end-systolic volume (Table 1). Mean wall thickness was greater with both multidetector CT and cardiac MR in the concentric remodeling group compared with the control group but was not significantly different (11.8 vs 10.8 mm, respectively, P > .05). In contrast to the above metrics, mean radial and circumferential strain for both multidetector CT and cardiac MR were significantly different in the cardiomyopathy groups compared with the control group (Table 2), suggesting greater sensitivity of the strain measures.

Figure 3 depicts comparison of strain values for multidetector CT versus tagged cardiac MR for each of the 16 segments. For peak radial strain, cardiac MR absolute strain values were higher than multidetector CT values, with a mean difference of −3.0% ± 4.2 (Fig 3, C). For peak circumferential strain, cardiac MR absolute strain values were lower than the multidetector CT values, with a mean difference of −2.4% ± 2.3 (Fig 3, D). Strain values for multidetector CT compared with cardiac MR showed better agreement in the radial direction than in the circumferential direction (r = 0.55, P = .03 vs r = 0.40, P = .13, respectively). Inspection of the Bland-Altman plot did not reveal any systematic bias.

Figure 3:

Graphs compare strain values for harmonic phase analysis of tagged cardiac MR images (HARP) and multimodality tissue tracking (MT T ) analysis of multidetector CT images according to the American Heart Association 16-segment model. Radial strain determined with, A, regression analysis and, C, Bland-Altman analysis between multidetector CT and tagged cardiac MR imaging. Circumferential strain determined with, B, regression analysis and, D, Bland-Altman analysis between multidetector CT and tagged cardiac MR imaging.

There was good interobserver agreement (ICC = 0.45) and excellent intraobserver agreement (ICC = 0.85). Multimodality tissue tracking for multidetector CT strain analysis required 69 seconds ± 2 per two-dimensional section compared with 175 seconds ± 4 per two-dimensional section for harmonic phase analysis for tagged cardiac MR.

Discussion

Comprehensive evaluation of myocardial disease involves both global and regional evaluation of myocardial function. In this study, we evaluated animals displaying both eccentric and concentric myocardial remodeling (10) along with supporting histologic analysis. We found that mean radial and circumferential strain, measured with both multidetector CT and cardiac MR imaging, was significantly different in the diseased groups than in the control group. The results indicate that multidetector CT regional strain analysis has the potential to detect abnormalities in myocardial function in cardiomyopathy in a manner similar to cardiac MR strain analysis.

Previous studies have shown that multidetector CT can accurately assess global metrics of myocardial structure and function, such as ejection fraction, LV mass, and LV volumes (16,17). In such studies, cardiac MR is frequently the standard of reference, a method we continue in the current study. However, myocardial disease usually proceeds from regional to global abnormalities. Regional analysis of myocardial structure has been investigated with cine multidetector CT and is typically evaluated in a semiquantitative fashion; wall motion is scored visually as normokinetic, hypokinetic, akinetic, or dyskinetic (16,18). Alternatively, percentage change in wall thickness can also quantify regional myocardial function (19,20). These anatomic approaches are particularly effective for evaluation of myocardial scar related to infarction. This has led to research such as ours investigating the quantification of regional cardiac strain.

An aspect of the current study is the comparison of both the reference standard (cardiac MR) and multidetector CT with relevant histologic changes in the myocardium. In addition, we focused on a disease model where indexes of global function or wall-thickening measure showed only subtle changes in response to the disease process. Previously, Helle-Valle et al (7) showed abnormalities with multidetector CT regional strain (21) in 16 patients with myocardial infarction. For myocardial infarction, late gadolinium enhancement cardiac MR is a standard of reference that has been shown to have excellent agreement with histologic analysis for focal scars. However, approximately 50% of patients with heart failure have normal ejection fraction, typically without focal myocardial scar. The pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction is very challenging to identify by using conventional anatomic cardiac MR or multidetector CT indexes of structure and function and often includes myocardial remodeling and fibrosis (22,23). Collagen deposition in the myocardium is a common end point of many diseases of the myocardium, as well as a mechanism that is also present in advanced aging (24). As hypertension progresses and becomes quite severe, LV remodeling occurs. In this study, the degree of systolic hypertension was insufficient to result in large functional change, but definite differences between control and cardiomyopathy groups were identified when regional LV function was evaluated.

Our results showed that radial strain obtained by using multidetector CT was in better agreement with radial strain obtained by using cardiac MR compared with comparisons of circumferential strain (Fig 3). Radial strain evaluation may be the strength of multidetector CT due to the high spatial resolution of the method (< 1 mm). This should allow accurate tracking of high-contrast regions at the endocardial and epicardial borders. However, for midwall circumferential strain, no CT features are typically available for tracking. By comparison, cardiac MR grids allow accurate tracking of midwall circumferential strain. In our study, as well as that of Helle-Valle (7), improved speed of analysis was present for multidetector CT compared with cardiac MR tagging.

An alternative approach to regional analysis of myocardial function with cine multidetector CT is available. The stretch quantifier for endocardial engraved zones, or SQUEEZ, algorithm allows evaluation of endocardial deformation, although a simple mathematical relation between strain and SQUEEZ deformation may not be found (25). These factors lead to our further investigation of cardiac strain in multidetector CT.

Limitations of this study include high temporal resolution for cine multidetector CT function, which may result in high radiation exposure. Technologic innovations in model-based iterative reconstruction and low tube voltage imaging are tools that have resulted in lower radiation dose. The number of animals in each group was small, and larger sample sizes may have shown that global function parameters could help detect differences between groups. Ultimately, translational studies in humans are needed, although generally histologic information is not available in human studies.

In conclusion, our results suggest that cine multidetector CT can be used to detect regional dysfunction in an experimental model of cardiomyopathy in a manner comparable to cardiac MR tagging. This study points to the potential of cine multidetector CT to allow comprehensive evaluation of myocardial function.

Advance in Knowledge

■ Myocardial strain analysis of cine multidetector CT images helps identify differences between control and cardiomyopathy groups (P < .05 for comparison to both tagged cardiac MR and histologic findings).

Implication for Patient Care

■ Strain analysis of the left ventricle with cine multidetector CT has the potential to be part of a comprehensive evaluation of the myocardial and coronary anatomy and function in patient studies.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge Fady Dawoud, PhD, for his efforts in the experimental work and preparation.

Received October 4, 2014; revision requested November 4; final revision received December 4; accepted December 22; final version accepted January 20, 2015.

Supported by the Oxford Cambridge NIH Training Program and a University of Missouri–Institute of Clinical and Translational Science Project Grant.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program CL090019-04 and EB000072-04.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: M.T.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.W. disclosed no relevant relationships. F.S.R. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.Y. disclosed no relevant relationships. D.V. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.D.V. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. A.L. disclosed no relevant relationships. J.A.C.L. Activities related to the present article: institution received grant support from Toshiba Medical Systems. Activities not related to the present article: institution received grant support from Toshiba Medical Systems. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. J.A.N. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.E. disclosed no relevant relationships. D.A.B. disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviations:

- ICC

- intraclass correlation coefficient

- LV

- left ventricle

References

- 1.Nikolaou K, Knez A, Rist C, et al. Accuracy of 64-MDCT in the diagnosis of ischemic heart disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187(1):111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton-Craig CR, Friedman D, Achenbach S. Cardiac computed tomography: evidence, limitations and clinical application. Heart Lung Circ 2012;21(2):70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewey M, Teige F, Schnapauff D, et al. Noninvasive detection of coronary artery stenoses with multislice computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Intern Med 2006;145(6):407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewey M, Hamm B. Cost effectiveness of coronary angiography and calcium scoring using CT and stress MRI for diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Eur Radiol 2007;17(5):1301–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shehata ML, Cheng S, Osman NF, Bluemke DA, Lima JA. Myocardial tissue tagging with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2009;11(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tee M, Noble JA, Bluemke DA. Imaging techniques for cardiac strain and deformation: comparison of echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance and cardiac computed tomography. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2013;11(2):221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helle-Valle TM, Yu WC, Fernandes VRS, Rosen BD, Lima JA. Usefulness of radial strain mapping by multidetector computer tomography to quantify regional myocardial function in patients with healed myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2010;106(4):483–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mewton N, Liu CY, Croisille P, Bluemke D, Lima JA. Assessment of myocardial fibrosis with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57(8):891–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiemstra JA, Gutiérrez-Aguilar M, Marshall KD, et al. A new twist on an old idea. II. Cyclosporine preserves normal mitochondrial but not cardiomyocyte function in mini-swine with compensated heart failure. Physiol Rep 2014;2(6):e12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiemstra JA, Liu S, Ahlman MA, et al. A new twist on an old idea: a two-dimensional speckle tracking assessment of cyclosporine as a therapeutic alternative for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Physiol Rep 2013;1(7):e00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall KD, Muller BN, Krenz M, et al. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: chronic low-intensity interval exercise training preserves myocardial O2 balance and diastolic function. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;114(1):131–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emter CA, Tharp DL, Ivey JR, Ganjam VK, Bowles DK. Low-intensity interval exercise training attenuates coronary vascular dysfunction and preserves Ca²⁺-sensitive K⁺ current in miniature swine with LV hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011;301(4):H1687–H1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osman NF, Kerwin WS, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Cardiac motion tracking using CINE harmonic phase (HARP) magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 1999;42(6):1048–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cademartiri F, Nieman K, van der Lugt A, et al. Intravenous contrast material administration at 16-detector row helical CT coronary angiography: test bolus versus bolus-tracking technique. Radiology 2004;233(3):817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogawa K, Hozumi T, Sugioka K, et al. Usefulness of automated quantitation of regional left ventricular wall motion by a novel method of two-dimensional echocardiographic tracking. Am J Cardiol 2006;98(11):1531–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annuar BR, Liew CK, Chin SP, et al. Assessment of global and regional left ventricular function using 64-slice multislice computed tomography and 2D echocardiography: a comparison with cardiac magnetic resonance. Eur J Radiol 2008;65(1):112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asferg C, Usinger L, Kristensen TS, Abdulla J. Accuracy of multi-slice computed tomography for measurement of left ventricular ejection fraction compared with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol 2012;81(5):e757–e762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu YW, Tadamura E, Yamamuro M, et al. Estimation of global and regional cardiac function using 64-slice computed tomography: a comparison study with echocardiography, gated-SPECT and cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Int J Cardiol 2008;128(1):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bax JJ. Imaging: myocardial thinning is not always transmural scarring. Nat Rev Cardiol 2013;10(7):370–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah DJ, Kim HW, James O, et al. Prevalence of regional myocardial thinning and relationship with myocardial scarring in patients with coronary artery disease. JAMA 2013;309(9):909–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abraham TP, Nishimura RA. Myocardial strain: can we finally measure contractility? J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37(3):731–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Díez J. Mechanisms of cardiac fibrosis in hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007;9(7):546–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martos R, Baugh J, Ledwidge M, et al. Diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: improved accuracy with the use of markers of collagen turnover. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11(2):191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olivetti G, Giordano G, Corradi D, et al. Gender differences and aging: effects on the human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26(4):1068–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pourmorteza A, Schuleri KH, Herzka DA, Lardo AC, McVeigh ER. A new method for cardiac computed tomography regional function assessment: stretch quantifier for endocardial engraved zones (SQUEEZ). Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;5(2):243–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]