Abstract

Systemic inflammation is accompanied by an increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and by either fever or hypothermia (or both). To study aseptic systemic inflammation, it is often induced in rats by the intravenous administration of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Knowing that bilirubin is a potent ROS scavenger, we compared responses to LPS between normobilirubinemic Gunn rats (heterozygous, asymptomatic; J/+) and hyperbilirubinemic Gunn rats (homozygous, jaundiced; J/J) to establish whether ROS mediate fever and hypothermia in aseptic systemic inflammation. These two genotypes correspond to undisturbed versus drastically suppressed (by bilirubin) tissue accumulation of ROS, respectively. A low dose of LPS (10 μg/kg) caused a typical triphasic fever in both genotypes, without any intergenotype differences. A high dose of LPS (1,000 μg/kg) caused a complex response consisting of early hypothermia followed by late fever. The hypothermic response was markedly exaggerated, whereas the subsequent fever response was strongly attenuated in J/J rats, as compared to J/+ rats. J/J rats also tended to respond to 1,000 μg/kg with blunted surges in plasma levels of all hepatic enzymes studied (alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transferase), thus suggesting an attenuation of hepatic damage. We propose that the reported exaggeration of LPS-induced hypothermia in J/J rats occurs via direct inhibition of nonshivering thermogenesis by bilirubin and possibly via a direct vasodilatatory action of bilirubin in the skin. This hypothermia-exaggerating effect might be responsible, at least in part, for the observed tendency of J/J rats to be protected from LPS-induced hepatic damage. The attenuation of the fever response to 1,000 μg/kg could be due to either direct actions of bilirubin on thermoeffectors or the ROS-scavenging action of bilirubin. However, the experiments with 10 μg/kg strongly suggest that ROS signaling is not involved in the fever response to low doses of LPS.

Keywords: antioxidants, bilirubin, fever, Gunn rats, hepatic damage, lipopolysaccharides, LPS, liver, reactive oxygen species, ROS, transferases

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- GGT

gamma-glutamyl transferase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NO

nitric oxide

- PG

prostaglandin

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Ta

ambient temperature

- Tb

body temperature

Introduction

Fever and hypothermia are symptoms of infection and inflammation. They are triggered via the production and release of endogenous proinflammatory mediators, including prostaglandin (PG) E2, by pathogen-sensing immune cells in peripheral tissues and in the brain.1-5 Intracellular signaling cascades activated by these endogenous mediators are complex and involve lipid, peptide, gaseous, and other messengers (for review, see reference 6).

They also include the reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion, and nitric oxide (NO).7,8 ROS are unstable, short-lived molecules that are thought to have 2 major functions. First, they are downstream molecular effectors of immune cell activation and, as such, are directly involved in killing and clearing microbial pathogens.9 Second, they are messengers within several intracellular signaling pathways and, in this role, affect multiple cell functions.10 Signaling properties of ROS are based on their ability to interact with many intracellular proteins, including redox-sensitive transcriptional factors and ion channels, as well as metal-containing enzymes responsible for production of proinflammatory mediators (for review, see reference 11).

While production of ROS by different cells and tissues in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS; often referred to as endotoxin) is well documented (for review, see reference 8), it is not clear whether ROS play roles in fever and hypothermia, the 2 thermoregulatory responses to LPS. Riedel et al.12,13 has proposed that oxidative stress is a crucial component in the pathogenesis of LPS fever, but the data used to substantiate their proposal are difficult to interpret. Riedel et al.12,13 observed an attenuation of LPS fever by high doses of dithiotreitol, methylene blue, aspirin, or α-lipolic acid and attributed fever-attenuating effects of these compounds to their free radical-scavenging action. However, all these compounds are nonselective radical scavengers; they also inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX),14 guanylyl cyclase,15 and secretory phospholipase A216 —important enzymes participating in the inflammatory response to LPS. Hence, the observed attenuation of LPS fever might have been due to inhibition of COX and other enzymes and not due to free radical scavenging.

Further complicating the issue, most exogenous ROS scavengers are water soluble and, therefore, can neutralize efficiently only substances dissolved in water (but not in lipids), whereas a large pool of free radicals accumulates in cellular membranes as lipoperoxides.17 These lipoperoxides are important mediators of oxidative stress, but they cannot be inactivated by conventional administration of water-soluble ROS scavengers. To dissect the roles of membrane ROS requires using lipophilic antioxidants.

Bilirubin is the end product of heme catabolism in mammals. This lipophilic molecule is generally considered a toxic waste that needs to be excreted.18,19 However, many studies have shown that bilirubin is a powerful antioxidant and efficient scavenger of lipoperoxide radicals in membranes.20,21 Hence, bilirubin can be used as a tool to inactivate water-insoluble, lipid-associated ROS. An established animal model to study the antioxidant activity of bilirubin in vivo is the Gunn rat model,22-24 named after C. H. Gunn, who characterized an autosomal recessive deficiency in uridine diphosphate glucuronyltransferase activity.25 This deficiency prevents the conjugation of bilirubin, which explains hyperbilirubinemia and neonatal jaundice in Gunn rats with the homozygous mutation (J/J), while heterozygous (J/+) rats are nonjaundiced. In J/J rats, the increased antioxidant activity due to hyperbilirubinemia has been proposed to contribute to the protection against the harmful effects of hyperoxia22 and of angiotensin II.23

Continuing our studies of the thermoregulatory responses to LPS in mutant rats (Zucker,26,27 Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima fatty,26,28 Koletsky,29 and Nagase analbuminemic30), the present work was focused on LPS-induced fever and hypothermia in J/J and J/+ Gunn rats. We also measured blood levels of biochemical markers of renal disfunction and hepatocyte damage in these rats following LPS administration.

Results

LPS-induced fever and hypothermia in Gunn rats

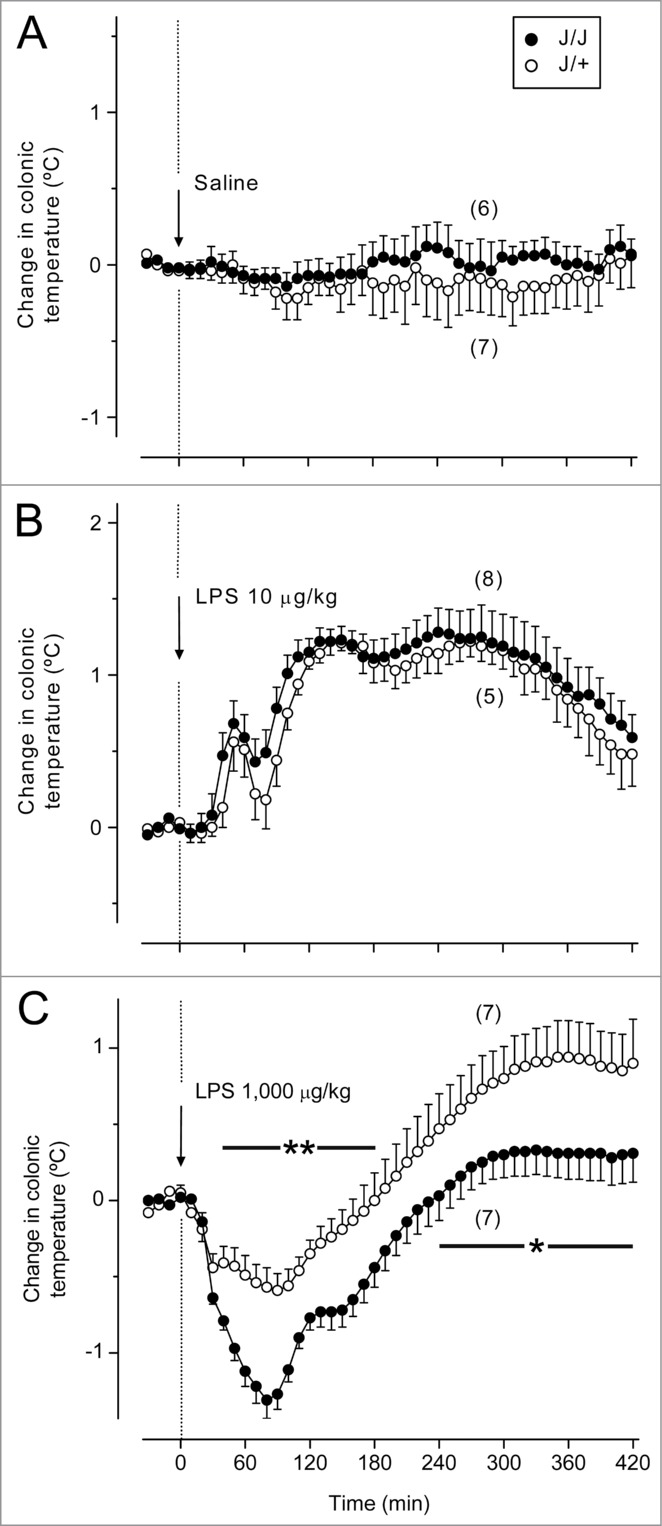

All experiments were conducted at an ambient temperature (Ta) of 30°C, which is within the thermoneutral zone for rats in our experimental setup.31 Two intravenous doses of LPS were used: the low (10 μg/kg) and the high (1,000 μg/kg). At 30°C, rats respond to the low dose of LPS with a polyphasic fever, and to the high dose with hypothermia followed by fever.3 In the present study, the intravenous injection of saline did not affect the colonic temperature (an index of deep body temperature, Tb) in either J/J or J/+ Gunn rats (Fig. 1A). To the low dose of LPS, both J/J and J/+ rats responded with a triphasic fever, with peaks at ∼50, 130, and 280 min post-injection (Fig. 1B). There were no significant differences in the Tb dynamics between the genotypes. To the high dose of LPS, J/+ rats responded with early hypothermia (nadir of –0.5°C at ∼90 min; P = 0.034 vs. saline) followed by fever (peak of 0.9°C at ∼360 min; P < 0.001 vs. saline) (Fig. 1C). The Tb response of J/J rats to the high dose of LPS was different from that of J/+ rats: the early hypothermic response (nadir of –1.2°C at ∼90 min, P < 0.001 vs. saline) was markedly exaggerated (P ≤ 0.004 for 40–180 min vs. J/+ rats), whereas the subsequent fever response (peak of 0.3°C, P = 0.039 vs. saline) was significantly attenuated (P < 0.05 for 240–420 min vs. J/+ rats).

Figure 1.

Deep (colonic) Tb responses of J/J and J/+ rats to the low (10 μg/kg, iv) and high (1,000 μg/kg, iv) doses of LPS. (A) Administration of the vehicle (saline) does not affect Tb in rats. (B) The low dose of LPS causes polyphasic fevers in J/J and J/+ rats, without any significant differences between the genotypes. (C) In J/+ rats, the high dose of LPS induces early hypothermia followed by late fever. In J/J rats, the hypothermic response is exaggerated, and the subsequent febrile response is attenuated, as compared to the J/+ controls. Time periods corresponding to significant intergenotype differences in the response to LPS are marked as * (P < 0.05) or ** (P < 0.01).

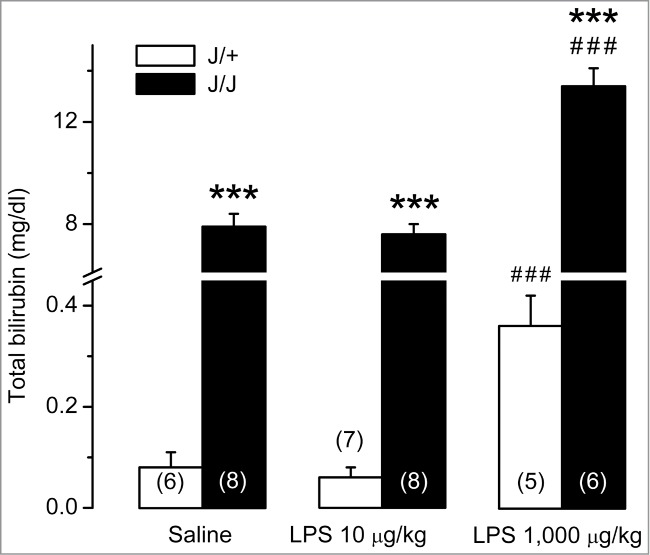

Plasma bilirubin in Gunn rats

Since LPS administration could induce liver failure, thereby causing (or exaggerating) hyperbilirubinemia, we examined blood bilirubin levels in J/J and J/+ rats under basal conditions and in LPS-induced systemic inflammation. As expected, the total plasma bilirubin level in saline-treated J/J rats was higher (by 2 orders of magnitude) than that in J/+ rats (P < 0.001, Fig. 2). The low dose of LPS did not affect the total bilirubin level in either genotype. However, in response to the injection of the high dose of LPS, the total bilirubin level surged in both J/+ and J/J rats (P < 0.001 vs. saline, for both genotypes). In J/J rats treated with the high dose of LPS, the total plasma bilirubin level remained higher than in J/+ controls (P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Blood bilirubin levels in J/J and J/+ rats. The total bilirubin level in blood plasma is dramatically higher in saline-treated J/J rats than in saline-treated J/+ controls. The low dose of LPS (10 μg/kg, iv) does not change the bilirubin level in either genotype. In response to the high dose of LPS (1,000 μg/kg, iv), the total bilirubin level increases in both genotypes, but remains substantially higher in J/J rats than in J/+ controls. ***, P < 0.001, intergenotype difference in the response to LPS. ###, P < 0.001, LPS vs. saline difference within the same genotype.

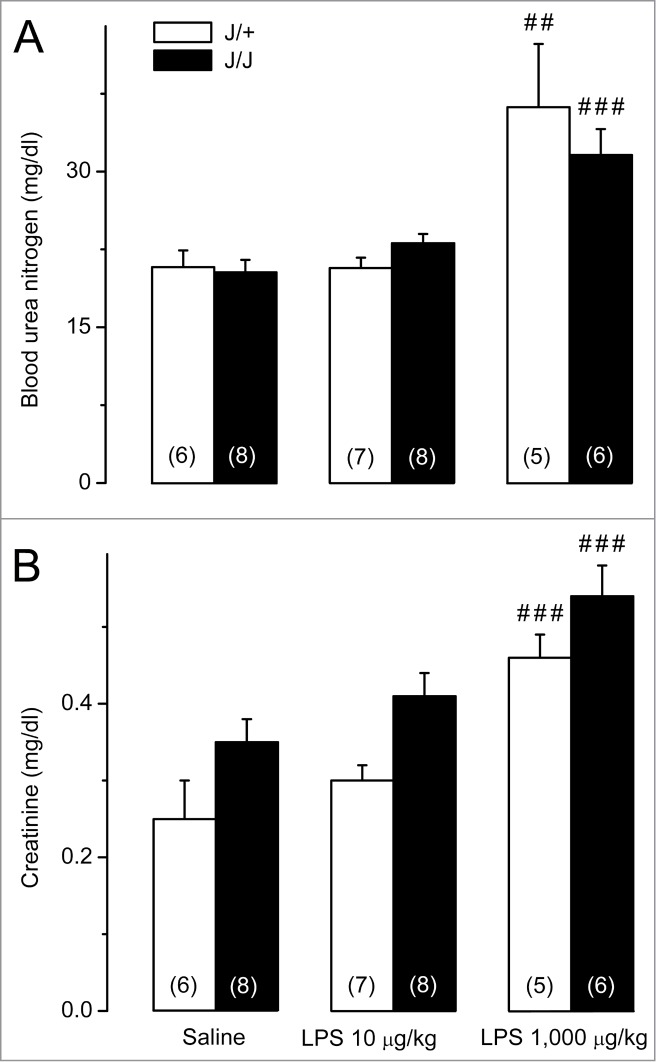

Renal disfunction and hepatic damage in Gunn rats after LPS administration

Plasma blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels were measured as markers of renal function.32 Neither of these markers differed significantly between saline-treated J/J and J/+ rats (Fig. 3). While administration of the low dose of LPS did not raise the renal disfunction markers, the high dose increased both BUN (Fig. 3A) and creatinine (Fig. 3B) in J/J (P ≤ 0.001 for both BUN and creatinine) and J/+ rats (P = 0.010 for BUN; P < 0.001 for creatinine) without any significant differences between the genotypes.

Figure 3.

Biochemical markers of renal disfunction in J/J and J/+ rats. (A) Plasma BUN levels do not differ between saline-treated J/J and J/+ rats and remain unchanged after administration of the low dose of LPS (10 μg/kg, iv). The high dose of LPS (1,000 μg/kg, iv) raises BUN in both genotypes, without any intergenotype difference. (B) Plasma creatinine levels do not differ between saline-treated J/J and J/+ rats and remain unchanged after administration of the low dose of LPS. The high dose of LPS raises plasma creatinine in both genotypes, without any intergenotype difference. Within each genotype, significant differences in the response to LPS (as compared to saline) are marked as ## (P < 0.01) or ### (P < 0.001).

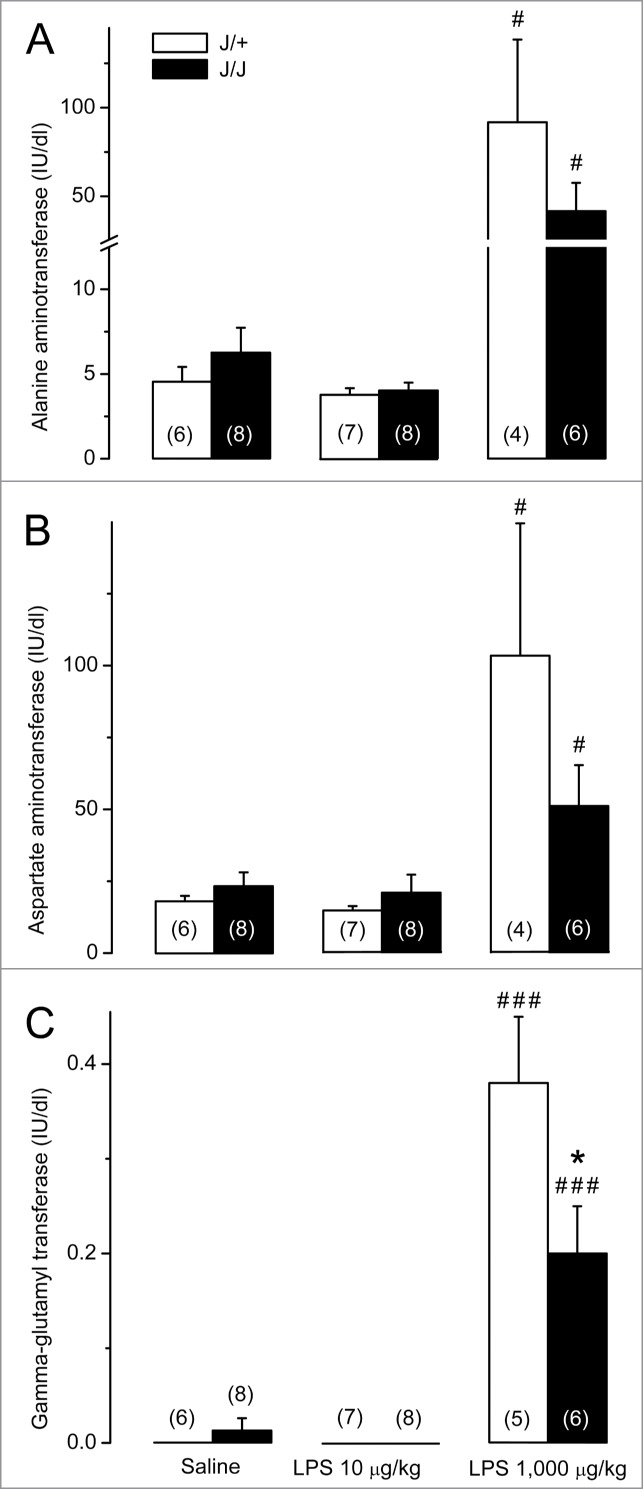

Plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) were used to assess hepatocyte damage.33 Activities of all 3 enzymes were within the normal range in J/J and J/+ rats after the injection of saline or the low dose of LPS (Fig. 4). When LPS was administered at the high dose, rats exhibited marked surges in ALT (P = 0.019 for J/+; P = 0.015 for J/J; Fig. 4A), AST (P = 0.021 for J/+; P = 0.041 for J/J; Fig. 4B), and GGT (P < 0.001 for both genotypes; Fig. 4C). In J/J rats, the surge was blunted for GGT (P = 0.042) and tended to be reduced for ALT (P = 0.208) and AST (P = 0.179), as compared to J/+ rats.

Figure 4.

Biochemical markers of hepatocyte damage in J/J and J/+ rats. (A) Plasma ALT levels do not differ between saline-treated J/J and J/+ rats and remain unchanged after the administration of the low dose of LPS (10 μg/kg, iv). In response to the high dose of LPS (1,000 μg/kg, iv), plasma ALT surges in both genotypes, but this surge tends to be blunted in J/J rats (as compared to the J/+ controls). (B) Plasma AST levels do not differ between J/J and J/+ rats after administration of saline or LPS at the low dose. In response to the high dose of LPS, AST surges in both genotypes, but the surge tends to be blunted in J/J rats). (C) Plasma GGT levels are near the detection threshold in J/J and J/+ rats after administration of saline or the low dose of LPS. Plasma GGT rises in both genotypes in response to the high dose of LPS, but the rise is significantly reduced in J/J rats. A significant (P < 0.05) intergenotype difference in the response to LPS is marked with *. Within each genotype, significant differences in the response to LPS (as compared to saline) are marked as # (P < 0.05) or ### (P < 0.001).

Discussion

LPS hypothermia is exaggerated in hyperbilirubinemic Gunn rats

The novel—and unexpected—finding of the present study is that hyperbilirubinemia in Gunn rats was associated with an exaggerated hypothermic response to LPS (Fig. 1C). This exaggeration is unlikely to be due to an attenuation of the ROS-mediated inflammatory signaling by bilirubin. Indeed, attenuating inflammatory signaling should decrease (not increase) the hypothermic response. Furthermore, while bilirubin, a potent ROS scavenger, has been shown repeatedly to attenuate inflammatory signaling,34-36 we did not find any literature data suggesting that it can amplify inflammatory signaling. An alternative, more plausible, mechanism of the exaggeration of LPS hypothermia might be an action of bilirubin on thermoeffectors. Gunn rats respond to administration of exogenous bilirubin (that further increases their hyperbilirubinemia) with a pronounced (∼3°C) drop in Tb.37 This drop is likely to reflect decreased thermogenesis, because bilirubin has been demonstrated to depress mitochondrial respiration in liver, heart, and brain tissues in vitro.38-40 And although brown adipose tissue (the main source of nonshivering, temperature-driven thermogenesis in rodents41) has not been studied, bilirubin is likely to have the same effect in brown fat as in all other tissues studied. A profound decrease in the threshold Tb for activation of thermogenesis is the principle autonomic thermoeffector mechanism of LPS-induced hypothermia.42 Although skin vasodilation is not the main mechanism of LPS-induced hypothermia,42 increased skin vasodilation in J/J rats could have contributed to their enhanced hypothermic response to LPS as well. Hyperbilirubinemia has been shown to attenuate the pressor effects of angiotensin II in Gunn rats23 and to lower angiotension II-dependent hypertension in mice,43,44 the latter effect being attributed to the blockade of superoxide production and possibly to enhanced vasorelaxation.43 In a study conducted in humans,45 hyperbilirubinemia exaggerated endothelium-dependent vasodilation of the brachial artery, which supplies subcutaneous and cutaneous tissues of the arm.

Hyperbilirubinemia differently affects fevers caused by low vs. high doses of LPS

The same action (or actions) on thermoeffectors could be responsible for the attenuation of the late fever response to the high dose of LPS in J/J rats, which was also observed in the present study (Fig. 1C). Since the thermoregulatory response to the high dose is a combination of early hypothermia and late fever, the exaggeration of the hypothermic response (and the resultant prolongation of this response) may be difficult to distinguish from an independent attenuation of the fever response.

Interestingly, the fever response to the low dose of LPS was not affected by hyperbilirubinemia in Gunn rats in our study (Fig. 1B), which is another novel observation. It suggests that ROS signaling is not involved in the febrile response, at least not to weak stimuli. It also extends our earlier conclusion that NO, a known ROS, is not involved in the pyrogenic signaling of LPS.46 However, it cannot be ruled out that hyperbilirubinemia blocks pro-pyretic ROS-mediated signaling triggered by high doses of LPS, i.e., doses that cause a prominent ROS response. For example, high doses of LPS (those that lead to shock and hypothermia) induce overexpression of the inducible NO synthase isoform,47,48 thus leading to the massive production of NO in rats.48,49 In contrast, lower (pyrogenic) doses of LPS suppress NO synthesis, possibly by inhibiting constitutive NO synthase isoforms.50,51

This proposed antipyretic, ROS-mediated action of bilirubin upon fevers caused by high doses of LPS would agree with several studies.12,13,52,53 In these studies, the febrile response to LPS was attenuated by antioxidants, whether water-soluble (such as methylene blue, dithiothreitol, aspirin, lipoic acid, natural antioxidants purified from spinach, or apocynin)12,13,52 or lipid-soluble (such as resveratrol and lipoic acid).12,53 Of those 4 studies, one53 involved administering an extremely high dose of LPS (4 mg/kg) to rats, whereas 3 other studies12,13,52 used 1–100 μg/kg doses in rabbits, the species that is ∼100 times more sensitive to LPS than rats. Interestingly, the high sensitivity of rabbits to LPS has been explained by the agile production of ROS in this species without a concomitant increase in the protective antioxidative enzymes.54 On the other hand, the relative resistance of rats to LPS has been ascribed to an increased activity of the endogenous antioxidant systems.54,55 It should also be noted that several ROS scavengers used in the studies discussed above12,13,52,53 inhibit the synthesis of PGE2, the principle mediator of fever,56,57 by acting on COX14,58-60 and secretory phospholipase A2.16 However, it is unlikely that all the reports of the fever-attenuating effects of ROS scavengers reflect an action on PG synthesis, because the antipyretic effect has been reported for multiple, structurally unrelated compounds. Furthermore, bilirubin (the focus of the present study) and several other ROS scavengers have not been shown to inhibit PGE2 synthesis, definitely not by an action independent from ROS neutralization. There are several studies showing that antioxidants (e.g., bilirubin, methylene blue, and apocynin) did not affect PGE2 synthesis or COX-2 expression in various models.61-64

Hyperbilirubinemia attenuates LPS-induced hepatic damage in Gunn rats

Compared to J/+ rats, J/J rats responded to the high dose of LPS with a blunted surge in GGT (Fig. 4C). The LPS-induced surges in 2 other transferases studied (ALT and AST) tended to be reduced, but the magnitude of the reduction did not reach the level of statistical significance (Fig. 4A, B). The revealed high sensitivity of GGT to hyperbilirubinemia was expected. Indeed, GGT is also a marker of oxidative stress,65 and the blood concentration of this enzyme is inversely related to the blood antioxidant activity.66,67 The observed effect of hyperbilirubinemia on the LPS-induced GGT response and the tendencies revealed (with regard to ALT and AST responses) agree with the previously reported protective action of bilirubin in endotoxin shock68 and other pathological conditions.69,70

The cytoprotective action of bilirubin is likely to be due to the suppression of oxidative stress, either directly (by scavenging ROS) or indirectly (by inhibiting the expression of free radical-generating enzymes, such as NO synthase and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase).68 By either mechanism, bilirubin potently suppresses the accumulation of lipophilic ROS in cell membranes,20,21 and the decreased accumulation of ROS prevents cell apoptosis and tissue injury associated with oxidative stress.70 Yet another mechanism of tissue protection by bilirubin in LPS-induced systemic inflammation could be the exaggeration of hypothermia. Hypothermia is an adaptive, active thermoregulatory response to high doses of LPS and other strong inflammatory stimuli.71 It involves cold-seeking behavior42,72,73 and is thought to be aimed at decreasing the metabolic requirements of tissues.3,71 In our studies,74,75 when rats were either allowed to select their preferred low Ta or maintained at a lower Ta chosen by the investigators during endotoxin shock or Escherichia coli infection, their survival rates increased. At least in some cases, the increased survival was coupled with a suppressed surge in ALT.75

Whereas markers of hepatocyte damage were affected by hyperbilirubinemia in the present study, markers of renal disfunction (BUN and creatinine) were not (Fig. 3), thus suggesting the lack of tissue protection in the kidneys. This is despite the fact that bilirubin has been shown to play a protective role in the kidneys, e.g., in diabetic nephropathy.76 The observed in the present study tissue specificity for the protective action of bilirubin may relate to the fact that the liver is the principal site for bilirubin metabolism. Due to this, bilirubin concentration in hepatocytes should be higher than anywhere else in the body, including renal epitheliocytes. Although bilirubin conjugation is defective in J/J rats,25 and these animals excrete only traces of bilirubin in the bile,77 they still have more than a 2-fold-higher concentration of bilirubin in the liver than in the kidneys.78

Summary and conclusions

We showed that hyperbilirubinemia in J/J Gunn rats was associated with a marked exaggeration of the early hypothermic response to the high dose of LPS (1,000 μg/kg), presumably through a direct inhibition of nonshivering thermogenesis by bilirubin and possibly also through a direct vasodilatatory action of bilirubin in the skin. This novel, hypothermia-exaggerating effect might be responsible, at least in part, for the observed tendency of J/J rats to respond to the high dose of LPS with attenuated hepatic damage.

Hyperbilirubinemia in Gunn rats was also associated with a deep attenuation of the late febrile response to the high (1,000 μg/kg) dose of LPS, but did not attenuate the fever response to the low (10 μg/kg) dose. The attenuation of the fever response to 1,000 μg/kg could be due to either direct actions of bilirubin on thermoeffectors (inhibition of nonshivering thermogenesis and induction of skin vasodilation) or the ROS-scavenging action of bilirubin attenuating pyrogenic signaling. However, the experiments with 10 μg/kg strongly suggest that ROS signaling is not involved in the fever response to low doses of LPS.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male J/J and J/+ Gunn rats were obtained from Harlan. They were housed in cages kept in a rack equipped with a Smart Bio-Pack ventilation system and Thermo-Pak temperature control system (Allentown Caging Equipment); the temperature of incoming air was maintained at 28°C. Standard rodent chow and tap water were available ad libitum. The room was on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 A.M.). The rats were housed in groups until they were subjected to surgery, after which they were caged singly. Animals were extensively handled and habituated to staying in wire-mesh conical confiners, which were later used in the experiments. At the time of the experiments the rats weighed 200–245 g, there was no significant difference between the body mass of rats of different genotypes. All procedures were conducted under protocols approved by the Legacy Health System and St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committees.

Intravenous catheterization

Four days before an experiment, each rat was implanted with a jugular catheter. The procedure was performed under ketamine-xylazine-acepromazine (55.6, 5.5, and 1.1 mg/kg ip, respectively) anesthesia and antibiotic (enrofloxacin, 1.1 mg/kg sc) protection. During the surgery, a rat was heated with a Deltaphase isothermal pad (Braintree Scientific). A small longitudinal incision was made on the ventral surface of the neck, left to the trachea. The left jugular vein was exposed, freed from its surrounding connective tissue, and ligated. A silicone catheter (ID 0.5 mm, OD 0.9 mm) filled with heparinized saline (50 U/ml) was passed into the superior vena cava through the jugular vein and secured in place with ligatures. The free end of the catheter was knotted, tunneled under the skin to the nape, and exteriorized. The wound on the ventral surface of the neck was sutured. To prevent postsurgical hypothermia, the animals were allowed to recover from anesthesia in an environmental chamber (model 3940; Forma Scientific) set to 28°C. The intravenous catheters were flushed with heparinized saline every other day.

Experimental setup

On the day of the experiment, each rat was placed in a confiner and equipped with a copper-constantan thermocouple (Omega Engineering) to measure colonic temperature (a measure of deep Tb). The thermocouple was inserted in the colon 10 cm deep beyond the anal sphincter and fixed to the tail with a loop of adhesive tape. To record Tb data, the thermocouple was plugged into a data logger (Cole-Parmer) connected to a computer. The rat in its confiner was then placed in an environmental chamber (Forma Scientific) set to a Ta of 30°C, which is a neutral Ta for rats in this setup.31 The implanted venous catheter was extended with a length of PE-50 tubing filled with saline. The extension was passed through a wall port and connected to a syringe filled with LPS or saline.

LPS administration

LPS from E. coli 0111:B4 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. A stock suspension of LPS (5 mg/ml) in pyrogen-free saline was stored at –20°C. On the day of the experiment, the stock was diluted to a final concentration of either 10 or 1,000 μg/ml. The diluted LPS suspension or saline was injected in a bolus (1 ml/kg) through the extension of the venous catheter. Deep Tb was monitored for 7 h after the injection.

Biochemical assays

To determine blood levels of total bilirubin and markers of renal disfunction and hepatocyte damage, rats were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine-acepromazine (5.6, 0.6, and 0.1 mg/kg ip, respectively) 24 h after LPS injection, and their arterial blood (5 ml) was collected by cardiac (left ventricle) puncture. The blood was immediately transferred to EDTA-containing Vacutainer tubes (Beckton Dickinson). The plasma was separated by centrifugation, aliquoted, and stored at –80°C until biological assays were performed. All samples were sent to the Legacy Central Laboratory, Portland, OR. ALT and AST activities in serum were determined according to the method of Reitman and Frankel,79 whereas GGT levels were assessed by the Szasz method.80 Total plasma bilirubin level, BUN, and creatinine concentration was determined according to the method described by Jendrassik et al.,81 Patton and Crouch,82 and Van Pilsum,83 respectively.

Statistical analysis

The Tb responses were compared by 2-way ANOVA followed by the Fisher least significant difference test by using Sigmaplot 11.0 (Systat Software). Blood levels of bilirubin and biochemical markers of renal and hepatic disfunction were compared with Student's t test. The effects were considered significant when P < 0.05. The data are reported as means ± SE.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This research has been supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grant R01NS41233 to AAR) and the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (grant PD 105532 to AG). AG acknowledges the Janos Bolyai Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

References

- 1. Wilhelms DB, Kirilov M, Mirrasekhian E, Eskilsson A, Kugelberg UO, Klar C, Ridder DA, Herschman HR, Schwaninger M, Blomqvist A, et al. Deletion of prostaglandin E2 synthesizing enzymes in brain endothelial cells attenuates inflammatory fever. J Neurosci 2014; 34:11684-90; PMID:25164664; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1838-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roth J, Blatteis CM. Mechanisms of Fever production and lysis: lessons from experimental LPS Fever. Compr Physiol 2014; 4:1563-604; PMID:25428854; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/cphy.c130033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Romanovsky AA, Almeida MC, Aronoff DM, Ivanov AI, Konsman JP, Steiner AA, Turek VF. Fever and hypothermia in systemic inflammation: recent discoveries and revisions. Front Biosci 2005; 10:2193-216; PMID:15970487; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2741/1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Saper CB, Romanovsky AA, Scammell TE. Neural circuitry engaged by prostaglandins during the sickness syndrome. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15:1088-95; PMID:22837039; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn.3159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steiner AA, Ivanov AI, Serrats J, Hosokawa H, Phayre AN, Robbins JR, Roberts JL, Kobayashi S, Matsumura K, Sawchenko PE, et al. Cellular and molecular bases of the initiation of fever. PLoS Biol 2006; 4:e284; PMID:16933973; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steiner AA, Branco LG. Fever and anapyrexia in systemic inflammation: intracellular signaling by cyclic nucleotides. Front Biosci 2003; 8:s1398-408; PMID:12957844; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2741/1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forman HJ, Torres M. Reactive oxygen species and cell signaling: respiratory burst in macrophage signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 166:S4-8; PMID:12471082; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1164/rccm.2206007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood 1998; 92:3007-17; PMID:9787133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Babior BM, Kipnes RS, Curnutte JT. Biological defense mechanisms. The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J Clin Invest 1973; 52:741-4; PMID:4346473; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI107236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lander HM. An essential role for free radicals and derived species in signal transduction. FASEB J 1997; 11:118-24; PMID:9039953 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thannickal VJ, Fanburg BL. Reactive oxygen species in cell signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2000; 279:L1005-28; PMID:11076791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Riedel W, Lang U, Oetjen U, Schlapp U, Shibata M. Inhibition of oxygen radical formation by methylene blue, aspirin, or alpha-lipoic acid, prevents bacterial-lipopolysaccharide-induced fever. Mol Cell Biochem 2003; 247:83-94; PMID:12841635; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1024142400835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Riedel W, Maulik G. Fever: an integrated response of the central nervous system to oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biochem 1999; 196:125-32; PMID:10448911; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1006936111474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Milton AS. Modern views on the pathogenesis of fever and the mode of action of antipyretic drugs. J Pharm Pharmacol 1976; 28:393-9; PMID:6743; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1976.tb04186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gruetter CA, Kadowitz PJ, Ignarro LJ. Methylene blue inhibits coronary arterial relaxation and guanylate cyclase activation by nitroglycerin, sodium nitrite, and amyl nitrite. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1981; 59:150-6; PMID:6112057; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1139/y81-025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jameel NM, Shekhar MA, Vishwanath BS. Alpha-lipoic acid: an inhibitor of secretory phospholipase A2 with anti-inflammatory activity. Life Sci 2006; 80:146-53; PMID:17011589; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Niki E. Antioxidants in relation to lipid peroxidation. Chem Phys Lipids 1987; 44:227-53; PMID:3311418; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0009-3084(87)90052-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McDonagh AF. Controversies in bilirubin biochemistry and their clinical relevance. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2010; 15:141-7; PMID:19932645; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.siny.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brites D. Bilirubin injury to neurons and glial cells: new players, novel targets, and newer insights. Semin Perinatol 2011; 35:114-20; PMID:21641483; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sedlak TW, Saleh M, Higginson DS, Paul BD, Juluri KR, Snyder SH. Bilirubin and glutathione have complementary antioxidant and cytoprotective roles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106:5171-6; PMID:19286972; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0813132106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stocker R, Yamamoto Y, McDonagh AF, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science 1987; 235:1043-6; PMID:3029864; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.3029864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dennery PA, McDonagh AF, Spitz DR, Rodgers PA, Stevenson DK. Hyperbilirubinemia results in reduced oxidative injury in neonatal Gunn rats exposed to hyperoxia. Free Radic Biol Med 1995; 19:395-404; PMID:7590389; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00032-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pflueger A, Croatt AJ, Peterson TE, Smith LA, d'Uscio LV, Katusic ZS, Nath KA. The hyperbilirubinemic Gunn rat is resistant to the pressor effects of angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2005; 288:F552-8; PMID:15536166; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajprenal.00278.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wallner M, Antl N, Rittmannsberger B, Schreidl S, Najafi K, Mullner E, Molzer C, Ferk F, Knasmuller S, Marculescu R, et al. Anti-genotoxic potential of bilirubin in vivo: damage to DNA in hyperbilirubinemic human and animal models. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013; 6:1056-63; PMID:23983086; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gunn CH. Hereditary acholuric jaundice: in a new mutant strain of rats. Journal of Heredity 1938; 29:137-9. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ivanov AI, Kulchitsky VA, Romanovsky AA. Does obesity affect febrile responsiveness? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25:586-9; PMID:11319666; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ivanov AI, Romanovsky AA. Fever responses of Zucker rats with and without fatty mutation of the leptin receptor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2002; 282:R311-6; PMID:11742853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ivanov AI, Kulchitsky VA, Romanovsky AA. Role for the cholecystokinin-a receptor in fever: a study of a mutant rat strain and a pharmacological analysis. J Physiol 2003; 547:941-9; PMID:12562931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Steiner AA, Dogan MD, Ivanov AI, Patel S, Rudaya AY, Jennings DH, Orchinik M, Pace TW, O'Connor K A, Watkins LR, et al. A new function of the leptin receptor: mediation of the recovery from lipopolysaccharide-induced hypothermia. FASEB J 2004; 18:1949-51; PMID:15388670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ivanov AI, Steiner AA, Patel S, Rudaya AY, Romanovsky AA. Albumin is not an irreplaceable carrier for amphipathic mediators of thermoregulatory responses to LPS: compensatory role of alpha1-acid glycoprotein. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2005; 288:R872-8; PMID:15576666; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00514.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Romanovsky AA, Ivanov AI, Shimansky YP. Selected contribution: ambient temperature for experiments in rats: a new method for determining the zone of thermal neutrality. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2002; 92:2667-79; PMID:12015388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramesh G, Zhang B, Uematsu S, Akira S, Reeves WB. Endotoxin and cisplatin synergistically induce renal dysfunction and cytokine production in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007; 293:F325-32; PMID:17494092; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajprenal.00158.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muftuoglu MA, Aktekin A, Ozdemir NC, Saglam A. Liver injury in sepsis and abdominal compartment syndrome in rats. Surg Today 2006; 36:519-24; PMID:16715421; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00595-006-3196-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kawamura K, Ishikawa K, Wada Y, Kimura S, Matsumoto H, Kohro T, Itabe H, Kodama T, Maruyama Y. Bilirubin from heme oxygenase-1 attenuates vascular endothelial activation and dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005; 25:155-60; PMID:15499042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kadl A, Pontiller J, Exner M, Leitinger N. Single bolus injection of bilirubin improves the clinical outcome in a mouse model of endotoxemia. Shock 2007; 28:582-8; PMID:17577133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kasap B, Soylu A, Ertoy Baydar D, Kiray M, Tugyan K, Kavukcu S. Protective effects of bilirubin in an experimental rat model of pyelonephritis. Urology 2012; 80:1389 e17-22; PMID:22995569; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.urology.2012.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Krukow N, Brodersen R. Toxic effects in the Gunn rat of combined treatment with bilirubin and orotic acid. Acta Paediatr Scand 1972; 61:697-703; PMID:5080650; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1972.tb15969.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kamisaka K, Gatmaitan Z, Moore CL, Arias IM. Ligandin reverses bilirubin inhibition of liver mitochondrial respiration in vitro. Pediatr Res 1975; 9:903-5; PMID:1196709; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1203/00006450-197512000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mustafa MG, Cowger ML, King TE. Effects of bilirubin on mitochondrial reactions. J Biol Chem 1969; 244:6403-14; PMID:4982202 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Noir BA, Boveris A, Garaza Pereira AM, Stoppani AO. Bilirubin: a multi-site inhibitor of mitochondrial respiration. FEBS Lett 1972; 27:270-4; PMID:4664225; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0014-5793(72)80638-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev 2004; 84:277-359; PMID:14715917; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Romanovsky AA, Shido O, Sakurada S, Sugimoto N, Nagasaka T. Endotoxin shock: thermoregulatory mechanisms. Am J Physiol 1996; 270:R693-703; PMID:8967396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stec DE, Storm MV, Pruett BE, Gousset MU. Antihypertensive actions of moderate hyperbilirubinemia: role of superoxide inhibition. Am J Hypertens 2013; 26:918-23; PMID:23482378; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/ajh/hpt038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vera T, Granger JP, Stec DE. Inhibition of bilirubin metabolism induces moderate hyperbilirubinemia and attenuates ANG II-dependent hypertension in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009; 297:R738-43; PMID:19571206; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.90889.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maruhashi T, Soga J, Fujimura N, Idei N, Mikami S, Iwamoto Y, Kajikawa M, Matsumoto T, Kihara Y, Chayama K, et al. Hyperbilirubinemia, augmentation of endothelial function, and decrease in oxidative stress in Gilbert syndrome. Circulation 2012; 126:598-603; PMID:22773454; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.105775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Steiner AA, Rudaya AY, Ivanov AI, Romanovsky AA. Febrigenic signaling to the brain does not involve nitric oxide. Br J Pharmacol 2004; 141:1204-13; PMID:15006900; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Titheradge MA. Nitric oxide in septic shock. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999; 1411:437-55; PMID:10320674; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0005-2728(99)00031-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bachetti T, Pasini E, Suzuki H, Ferrari R. Species-specific modulation of the nitric oxide pathway after acute experimentally induced endotoxemia. Crit Care Med 2003; 31:1509-14; PMID:12771626; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063269.35714.7E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jourd'heuil D, Gray L, Grisham MB. S-nitrosothiol formation in blood of lipopolysaccharide-treated rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 273:22-6; PMID:10873557; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Riedel W. Antipyretic role of nitric oxide during endotoxin-induced fever in rabbits. Int J Tissue React 1997; 19:171-8; PMID:9506319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Steiner AA, Antunes-Rodrigues J, McCann SM, Branco LG. Antipyretic role of the NO-cGMP pathway in the anteroventral preoptic region of the rat brain. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2002; 282:R584-93; PMID:11792670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lomnitski L, Carbonatto M, Ben-Shaul V, Peano S, Conz A, Corradin L, Maronpot RR, Grossman S, Nyska A. The prophylactic effects of natural water-soluble antioxidant from spinach and apocynin in a rabbit model of lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemia. Toxicol Pathol 2000; 28:588-600; PMID:10930047; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1177/019262330002800413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sebai H, Ben-Attia M, Sani M, Aouani E, Ghanem-Boughanmi N. Protective effect of resveratrol in endotoxemia-induced acute phase response in rats. Arch Toxicol 2009; 83:335-40; PMID:18754105; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00204-008-0348-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ben-Shaul V, Sofer Y, Bergman M, Zurovsky Y, Grossman S. Lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress in the liver: comparison between rat and rabbit. Shock 1999; 12:288-93; PMID:10509631; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00024382-199910000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lee KY, Perretta SG, Zar H, Mueller RA, Boysen PG. Increase in rat plasma antioxidant activity after E. coli lipopolysaccharide administration. Yonsei Med J 2001; 42:114-9; PMID:11293489; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3349/ymj.2001.42.1.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ivanov AI, Romanovsky AA. Prostaglandin E2 as a mediator of fever: synthesis and catabolism. Front Biosci 2004; 9:1977-93; PMID:14977603; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2741/1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Steiner AA, Hunter JC, Phipps SM, Nucci TB, Oliveira DL, Roberts JL, Scheck AC, Simmons DL, Romanovsky AA. Cyclooxygenase-1 or -2-which one mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced hypothermia? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2009; 297:R485-94; PMID:19515980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.91026.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Barbieri SS, Cavalca V, Eligini S, Brambilla M, Caiani A, Tremoli E, Colli S. Apocynin prevents cyclooxygenase 2 expression in human monocytes through NADPH oxidase and glutathione redox-dependent mechanisms. Free Radic Biol Med 2004; 37:156-65; PMID:15203187; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Egan RW, Paxton J, Kuehl FA, Jr. Mechanism for irreversible self-deactivation of prostaglandin synthetase. J Biol Chem 1976; 251:7329-35; PMID:826527 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kimura Y, Okuda H, Arichi S. Effects of stilbene derivatives on arachidonate metabolism in leukocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1985; 837:209-12; PMID:3931689; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0005-2760(85)90244-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Okamura T, Yoshida K, Toda N. Suppression by methylene blue of prostaglandin I2 synthesis in isolated dog renal arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1990; 254:198-203; PMID:2114477 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Salvemini D, Misko TP, Masferrer JL, Seibert K, Currie MG, Needleman P. Nitric oxide activates cyclooxygenase enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1993; 90:7240-4; PMID:7688473; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Paliege A, Pasumarthy A, Mizel D, Yang T, Schnermann J, Bachmann S. Effect of apocynin treatment on renal expression of COX-2, NOS1, and renin in Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2006; 290:R694-700; PMID:16467505; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00219.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mancuso C, Pistritto G, Tringali G, Grossman AB, Preziosi P, Navarra P. Evidence that carbon monoxide stimulates prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase activity in rat hypothalamic explants and in primary cultures of rat hypothalamic astrocytes. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1997; 45:294-300; PMID:9149104; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0169-328X(96)00258-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lee DH, Blomhoff R, Jacobs DR, Jr. Is serum gamma glutamyltransferase a marker of oxidative stress? Free Radic Res 2004; 38:535-9; PMID:15346644; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/10715760410001694026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lee DH, Gross MD, Jacobs DR, Jr. Association of serum carotenoids and tocopherols with gamma-glutamyltransferase: the Cardiovascular Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Clin Chem 2004; 50:582-8; PMID:14726472; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1373/clinchem.2003.028852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lim JS, Yang JH, Chun BY, Kam S, Jacobs DR, Jr., Lee DH. Is serum gamma-glutamyltransferase inversely associated with serum antioxidants as a marker of oxidative stress? Free Radic Biol Med 2004; 37:1018-23; PMID:15336318; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.06.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lanone S, Bloc S, Foresti R, Almolki A, Taille C, Callebert J, Conti M, Goven D, Aubier M, Dureuil B, et al. Bilirubin decreases nos2 expression via inhibition of NAD(P)H oxidase: implications for protection against endotoxic shock in rats. FASEB J 2005; 19:1890-2; PMID:16129699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ben-Amotz R, Bonagura J, Velayutham M, Hamlin R, Burns P, Adin C. Intraperitoneal bilirubin administration decreases infarct area in a rat coronary ischemia/reperfusion model. Front Physiol 2014; 5:53; PMID:24600401; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fphys.2014.00053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Oh SW, Lee ES, Kim S, Na KY, Chae DW, Chin HJ. Bilirubin attenuates the renal tubular injury by inhibition of oxidative stress and apoptosis. BMC Nephrol 2013; 14:105; PMID:23683031; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2369-14-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Romanovsky AA, Szekely M. Fever and hypothermia: two adaptive thermoregulatory responses to systemic inflammation. Med Hypotheses 1998; 50:219-26; PMID:9578327; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0306-9877(98)90022-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Almeida MC, Steiner AA, Branco LG, Romanovsky AA. Neural substrate of cold-seeking behavior in endotoxin shock. PLoS One 2006; 1:e1; PMID:17183631; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0000001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Almeida MC, Steiner AA, Branco LG, Romanovsky AA. Cold-seeking behavior as a thermoregulatory strategy in systemic inflammation. Eur J Neurosci 2006; 23:3359-67; PMID:16820025; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04854.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Romanovsky AA, Shido O, Sakurada S, Sugimoto N, Nagasaka T. Endotoxin shock-associated hypothermia. How and why does it occur? Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997; 813:733-7; PMID:9100963; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51775.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Liu E, Lewis K, Al-Saffar H, Krall CM, Singh A, Kulchitsky VA, Corrigan JJ, Simons CT, Petersen SR, Musteata FM, et al. Naturally occurring hypothermia is more advantageous than fever in severe forms of lipopolysaccharide- and Escherichia coli-induced systemic inflammation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2012; 302:R1372-83; PMID:22513748; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpregu.00023.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Fujii M, Inoguchi T, Sasaki S, Maeda Y, Zheng J, Kobayashi K, Takayanagi R. Bilirubin and biliverdin protect rodents against diabetic nephropathy by downregulating NAD(P)H oxidase. Kidney Int 2010; 78:905-19; PMID:20686447; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ki.2010.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kotal P, Van der Veere CN, Sinaasappel M, Elferink RO, Vitek L, Brodanova M, Jansen PL, Fevery J. Intestinal excretion of unconjugated bilirubin in man and rats with inherited unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatr Res 1997; 42:195-200; PMID:9262222; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1203/00006450-199708000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schmid R, Hammaker L. Metabolism and Disposition of C14-Bilirubin in Congenital Nonhemolytic Jaundice. J Clin Invest 1963; 42:1720-34; PMID:14083163; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI104858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Reitman S, Frankel S. A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. Am J Clin Pathol 1957; 28:56-63; PMID:13458125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Szasz G. A kinetic photometric method for serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase. Clin Chem 1969; 15:124-36; PMID:5773262 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Jendrassik L, Grof P. Simplified photometric methods for determination of blood-bilirubin. Biochemische Zeitschrift 1938; 297:81-9. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Patton CJ, Crouch SR. Spectrophotometric and kinetics investigation of Berthelot reaction for determination of ammonia. Analytical Chemistry 1977; 49:464-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/ac50011a034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Van Pilsum JF, Martin RP, Kito E, Hess J. Determination of creatine, creatinine, arginine, guanidinoacetic acid, guanidine, and methylguanidine in biological fluids. J Biol Chem 1956; 222:225-35; PMID:13366996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]