Abstract

P-glycoprotein (Pgp) [the product of the MDR1 (ABCB1) gene] at the blood-brain barrier (BBB) limits central nervous system (CNS) entry of many prescribed drugs, contributing to the poor success rate of CNS drug candidates. Modulating Pgp expression could improve drug delivery into the brain; however, assays to predict regulation of human BBB Pgp are lacking. We developed a transgenic mouse model to monitor human MDR1 transcription in the brain and spinal cord in vivo. A reporter construct consisting of ∼10 kb of the human MDR1 promoter controlling the firefly luciferase gene was used to generate a transgenic mouse line (MDR1-luc). Fluorescence in situ hybridization localized the MDR1-luciferase transgene on chromosome 3. Reporter gene expression was monitored with an in vivo imaging system following D-luciferin injection. Basal expression was detectable in the brain, and treatment with activators of the constitutive androstane, pregnane X, and glucocorticoid receptors induced brain and spinal MDR1-luc transcription. Since D-luciferin is a substrate of ABCG2, the feasibility of improving D-luciferin brain accumulation (and luciferase signal) was tested by coadministering the dual ABCB1/ABCG2 inhibitor elacridar. The brain and spine MDR1-luc signal intensity was increased by elacridar treatment, suggesting enhanced D-luciferin brain bioavailability. There was regional heterogeneity in MDR1 transcription (cortex > cerebellum) that coincided with higher mouse Pgp protein expression. We confirmed luciferase expression in brain vessel endothelial cells by ex vivo analysis of tissue luciferase protein expression. We conclude that the MDR1-luc mouse provides a unique in vivo system to visualize MDR1 CNS expression and regulation.

Introduction

The drug efflux transporter P-glycoprotein (Pgp) is the product of the ABCB1/MDR1 gene. Drug transporting Pgp is a critical part of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and essential in preventing the blood-to-brain penetration of substrates (Schinkel et al., 1995). However, BBB Pgp also prevents brain delivery of drugs acting on the central nervous system (CNS), including those for brain tumor treatment.

Cranial BBB Pgp is regulated by a number of signaling pathways. In mice the pregnane X receptor (PXR) mediates induction of BBB Pgp by a variety of ligands, including the prototypical mouse PXR agonist pregnenolone-16α-carbonitrile. The glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) has been shown to mediate dexamethasone induction of rodent BBB Pgp (Narang et al., 2008). Activators of the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), including 1,4-bis[2(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benezene and phenobarbital, induced Pgp protein and function in rat and mouse brain capillaries ex vivo (Wang et al., 2010). Spinal BBB Pgp is regulated by activators of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and Nrf2 (Campos et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014).

The human MDR1 promoter contains PXR and CAR regulatory sequences at about −8 kb (Geick et al., 2001), and human MDR1 transcription can be induced in human liver and intestinal cell models by prototypical PXR and CAR activators (Schuetz et al., 1996a; Hartley et al., 2004). However, data on regulation of human BBB MDR1 in vivo is lacking, despite the fact that there are numerous reasons to understand and predict how MDR1 is regulated at the human BBB in vivo (Miller, 2010). The most extensively described immortalized human BBB cells (hCMEC/D3) (Weksler et al., 2013) maintain a low level of Pgp expression but have barely detectable expression of PXR and CAR and failed to show PXR and CAR regulation of MDR1 (Dauchy et al., 2009). It is unclear whether the cultured cells fail to retain regulation seen in vivo or whether there are differences between rodents and humans in regulation of BBB MDR1. Mouse PXR and CAR are expressed in brain and spinal capillaries and regulate mouse Pgp expression (Bauer et al., 2004), and mice humanized with hPXR can similarly regulate mouse BBB Pgp (Miller et al., 2008). However, these models cannot predict the potential of the human MDR1 5′-regulatory sequences to respond to these same regulators in the brain in vivo.

A mouse mdr1a-luc model has previously been generated in which the luciferase reporter was inserted into the genomic locus of the mouse mdr1a gene by homologous recombination (Gu et al., 2009, 2013) and bioluminescent imaging was used to study in vivo transcription of the mouse mdr1a promoter. However, mdr1a transcription was not reported in the mdr1a-luc mouse CNS. To gain better understanding of human MDR1 regulation, we created a transgenic mouse model with the human MDR1 promoter driving a luciferase reporter. The MDR1-luc mouse demonstrated luciferase signal in the brain and spine that can be used to study real-time in vivo transcriptional regulation of the human MDR1 gene. In addition, we show that treatment of mice with elacridar (an inhibitor of Abcg2/Bcrp at the BBB) can improve the magnitude of the luciferase signal in the brain and spine, presumably by increasing the CNS accumulation of the known Bcrp substrate D-luciferin.

Materials and Methods

Materials

1,4-Bis[2(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benezene, elacridar, rifampin, and dexamethasone were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and sodium phenobarbital was purchased from J.T. Baker Inc. (Phillipsburg, NJ).

Animals

Friend virus B (FVB) mice were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY). All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in accordance with the U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Creation of MDR1-Luc Transgenic Mice

The human MDR1-luciferase plasmid was generated by amplifying the human MDR1 promoter (−9,912/+180, relative to the transcription initiation site) and ligating it into the KpnI/SmaI site of pGL3Basic (Promega, Madison, WI) as described previously (Schuetz et al., 2002). The transgene was linearized by restriction enzyme digestion and the purified fragment was microinjected into single cell-stage FVB embryos and implanted into pseudo-pregnant mice.

MDR1-Luc Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from mouse tails using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Two methods were used to determine the presence or absence of luciferase in genomic DNA. Luciferase [255 base pair (bp) fragment] was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified using primers lucS (TTCGCAGCCTACCGTGGTGTT) and lucAS (GGCAGACCAGTAGATCCAGAG) and HotMaster Taq DNA polymerase (5 Prime Inc., Gaithersburg, MD). PCR conditions included an initial denaturation (94°C for 2 minutes), followed by 32 cycles of denaturation (94°C for 20 seconds), annealing (55°C for 20 seconds), synthesis (65°C for 30 seconds), and a final synthesis (65°C for 1 minute). The amplicon was visualized on a 2% agarose gel. Alternatively, mice were genotyped using real-time PCR with specific probes designed to detect luciferase (Transnetyx, Cordova, TN). Insertion of the entire MDR1 promoter was confirmed by PCR amplification using genomic DNA from MDR1-luc mice and eight sets of human MDR1-specific primers that specifically amplified regions between −9447 and +180 bp of the human MDR1 promoter transgene.

Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Assay (MLPA) to Genotype Zygosity of MDR1-Luc Transgene Alleles

Since the exact insertion site of the MDR1-luc transgene was not known, MLPA was used to genotype transgene zygosity. During the MLPA, an oligonucleotide ligation reaction was performed, followed by PCR using a fluorescein-conjugated primer, such that the amount of PCR product generated for each genomic sequence was directly proportional to the number of input copies. The mice bearing Luc transgene alleles were analyzed by designing our own MLPA Luc probe set to have an amplification product size of 140 bp. Three control probes elsewhere in the mouse genome were used, with amplification products ranging in size from 108, 114, and 136 bp (Kozlowski et al., 2007). Each probe set was composed of a 5′ half-probe and a 3′ half-probe, each containing a unique target-specific sequence, a stuffer sequence, and universal primer sequences on their 5′ and 3′ ends (Kozlowski et al., 2007). All probes were synthesized at 25-N scale and purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY); the 3′ half-probes were synthesized with 5′ phosphate to facilitate ligation.

MLPA Reaction

All reagents except for the probe mixes were obtained from MRC-Holland (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and the reactions were performed according to the manufacturers’ protocol. The MLPA was performed by incubating 50 ng (10 ng/µl using DNA suspension buffer (TEKnova, Hollister, CA) of mouse tail genomic DNA in 5 µl at 98°C for 5 minutes, and then cooling to room temperature, mixing with 1.5 µl of Luc transgene-specific probe mixture (containing 1.5 fmol each probe) and 1.5 µl Selective Adaptor Ligation, Selective Amplification (SALSA) hybridization buffer, denaturing (95°C for 2 minutes), and hybridizing (60°C for 16 hours). Hybridized probes were then ligated at 54°C for 15 minutes by addition of 32 µl ligation mixture. Following heat inactivation, 40 µl ligation reaction was mixed with 10 µl PCR mixture (SALSA polymerase, dNTPs, and universal primers, one of which was labeled with fluorescein), and subjected to PCR (35 cycles). Amplification products were diluted in water (1:10) and then 1:9 in Hi-Di formamide (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY) containing 1/36 volume of GeneScan 500 LIZ size standard (Applied Biosystems), to a final dilution of 20- to 200-fold, and then were separated by size on a 3730XL DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Electropherograms were analyzed by GeneMapper version 5 (Applied Biosystems), and peak height data were exported to an Excel table. Normalization of peak height data was done by dividing each Luc transgene peak height by the average signal from three control probes, followed by division by a similar value calculated from a set of reference samples known to be heterozygotes for the transgene allele. This ratio reflects the copy number of the Luc transgene.

MLPA Luc Probe Set for Mouse Transgene.

The following probe set was used: 5′ half-probe [(75 nucleotide (nt)] [5′ universal prime, GGGTTCCCTAAGGGTTGGA (19 nt); 5′ stuffer, cgctactact (10 nt), 5′ target, AATTGGAATCCATCTTGCTCCAACACCCCAACATCTTCGACGCAGG (46 nt)] and 3′ half-probe (65 nt) [3′ target, TGTCGCAGGTCTTCCCGACGATGACGCCGGTGAACTT (37 nt); 3′ stuffer, gacca (5 nt); and 3′ universal primer, TCTAGATTGGATCTTGCTGGCGC (23 nt)], with a total product length of 140 bp. The control probe sets were used exactly as indicated (Kozlowski et al., 2007). The probe set consisted of a 5′ half-probe and a 3′ half-probe. Each probe contained universal primer, stuffer, and target sequences, the latter of which was specific for the transgene being assessed. The total length of the PCR product assessed by capillary electrophoresis is shown by the total product length. The primers used for PCR were SALSA forward primer (labeled), *GGGTTCCCTAAGGGTTGGA; and SALSA reverse primer (unlabeled), GTGCCAGCAAGATCCAATCTAGA.

MDR1-Luc Transgene Localization by Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

The purified MDR1-luc plasmid was labeled with digoxigenin-11dUTP (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN) by nick translation, combined with sheared mouse DNA and a biotinylated chromosome 3 centromere-specific probe (Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD), and hybridized to metaphase chromosomes derived from the lungs of two heterozygous MDR1-luc transgenic mice in a solution containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, and 2× standard saline citrate. Probes were detected by incubating the slide in fluorescein-labeled anti-digoxigenin antiserum for the MDR1-luc transgene and a biotin-labeled centromeric control probe for chromosome 3 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The chromosomes were then stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and analyzed. To determine a band assignment for the transgene insertion sites, measurements were made of the specifically hybridized chromosome to determine the position of the transgene relative to the heterochromatic-euchromatic boundary and the telomere of the specifically hybridizing chromosome. The MDR1-luc mice were found to have a transgene insertion that is 10% of the distance from the heterochromatic-euchromatic boundary to the telomere of chromosome 3, an area that corresponds to band 3A to 3B.

In Vivo Bioluminescent Imaging of MDR1-Luc Reporter Mice

Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane gas (2%, inhalation) and given an i.p. injection of D-firefly luciferin (240 mg/kg) (Gold Biotechnology, St. Louis, MO). Mice were placed into the chamber of a Xenogen IVIS 200 imaging system and bioluminescence images were obtained under isoflurane anesthesia using 1 minute exposures beginning 10 minute after D-luciferin injection (http://www.xenogen.com/demo4.html). The images were quantitatively analyzed by Living Image version 4.3.1 image analysis software (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA). Total bioluminescence measurements (photon/s) were quantified over a contour drawn around brain and coronal slices. Results were repeated two to three times in independent animals. All in vivo images are scaled to maximum intensity of 1 × 105 photons/s/cm2/sr.

MDR1-Luc Mice Drug Treatments

Female MDR1-luc transgenic mice (8–12 weeks) (n = 3–5/group) were treated with drugs that were selected based on clinical relevance and previous data demonstrating that the drugs are prototypical Pgp inducers (Supplemental Material; Supplemental Table 1). Some mice were treated by oral gavage with elacridar (100 mg/kg) suspension (prepared in 0.5% methocel 60 HG and 1% Tween 80 (Sigma) to obtain a 10 mg/ml formulation) the final 4 hours before in vivo imaging.

Ex Vivo Imaging of Bioluminescence in Brain Slices from MDR1-Luc Transgenic Mice

After in vivo imaging, mice were immediately sacrificed under anesthesia by carbon dioxide gas following cervical dislocation. Whole brain was immediately dissected out of the skull and dorsal and ventral of the brain image were taken. The brain was immobilized on a brain slicer matrix (Zivic Instruments, Pittsburgh, PA) and coronally sliced at 2 mm thickness. The brain slices were placed into individual wells of a 12-well plate. D-luciferin was directly reapplied on each brain slice and a coronal image was taken from both sides of the slices. Dorsal, ventral, sagittal, and coronal images were scaled to a maximum intensity of 1 × 105 photons/s/cm2/sr, while microdissected brain images were scaled to a maximum intensity of 3.5 × 104 photons/s/cm2/sr.

Quantitation of Fluroescently Immunostained Mouse Pgp and CD31 in Coronal Brain Slices

MDR1-luc adult mice were perfused with cold phosphate-buffered saline and 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were removed and processed for paraffin embedding. Embedded tissue was cut at 4 µm thickness. Slides were deparaffinized and antigens retrieved with Target Retrieval solution pH 6.0 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) in a pressure cooker for 15 minutes. After retrieval, slides were rinsed, treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide, and blocked with 3% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBST). Slides were incubated with purified rabbit anti-Pgp antibody (1:50,000) (raised to a peptide containing amino acids 555–575 of human Pgp prepared by Dr. John Schuetz, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN) and goat anti CD31 IgG (1:300) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 1 hour. Stained slides were rinsed three times in PBST and then incubated with Alexa donkey anti-rabbit 568 or Alexa donkey anti-goat 488 secondary antibody (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) at 1:500 for 1 hour and coverslipped with Permount (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Imaging was performed on a wide-field Nikon TE2000S microscope (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, NY) equipped with a 20× 0.75NA Plan Apochromat Lens, (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, NY) and a Photometrics Coolsnap K4 camera (Photometric Scientific, Tucson, AZ). Fluorescent images were captured by using 3 × 3 binning and cropping to the center of the chip, resulting in individual images that were 512 × 512 pixels. Images were captured as montages and were typically comprised of 1000–1300 images. Quantitation was performed using NIS Elements software (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, NY). Each channel was thresholded to distinguish the signal above the background, and the mean intensities for each thresholded channel were calculated. In total, 18 measurements of 39,992 µm2 size (the region of interest) were randomly selected per region and taken for both the frontal cortex and cerebellum. Numerical values were determined for binary area [total area of pixels that show any intensity within the threshold for the region of interest (and this could be bright or dim)]; binary sum (total intensity within the set threshold); and binary mean intensity (sum intensity/binary area). To determine differences in vessel density in each region, the binary area for CD31 in the frontal cortex versus cerebellum was compared. To determine the expression of Pgp per brain capillary in each region we calculated the mean Pgp intensity/mean CD31 intensity for the frontal cortex versus cerebellum.

All statistical calculations were performed using statistical program R (a language and environment for statistical analysis; http://www.R-project.org). Group differences were analyzed nonparametrically using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare the mean intensity of Pgp (normalized to the mean intensity of CD31) for each square between the frontal cortex and cerebellum.

Colorimetric Immunostaining of Luciferase in Mouse Brain

Adult mice (MDR1-luc and FVB controls) were perfused with cold phosphate-buffered saline and 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and processed for paraffin embedding. Embedded tissue was cut at 4 μm thickness. These slides were deparaffinized and antigens were retrieved with Target Retrieval solution pH 6 (Dako) in a pressure cooker for 15 minutes. After retrieval, slides were rinsed, treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide, and blocked with Background Sniper (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA), followed by primary antibody staining with rabbit anti-luciferase IgG (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) or rabbit IgG isotype control antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) in a humidified chamber overnight at 4°C. Stained slides were rinsed three times in PBST (0.3% Triton X-100), and then incubated with rabbit-on-rodent HRP-polymer secondary (Biocare Medical). Slides were rinsed three times in PBST, and then color detection was completed using diaminobenzidine (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and counterstained with diluted hematoxylin (1:7 dilution Thermo Fisher Scientific). Slides were then dehydrated and coverslipped with Permount (#SP15-500, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Light microscopy was performed at 60× on a Nikon microscope.

Results

MDR1-Luc Transgenic Mice.

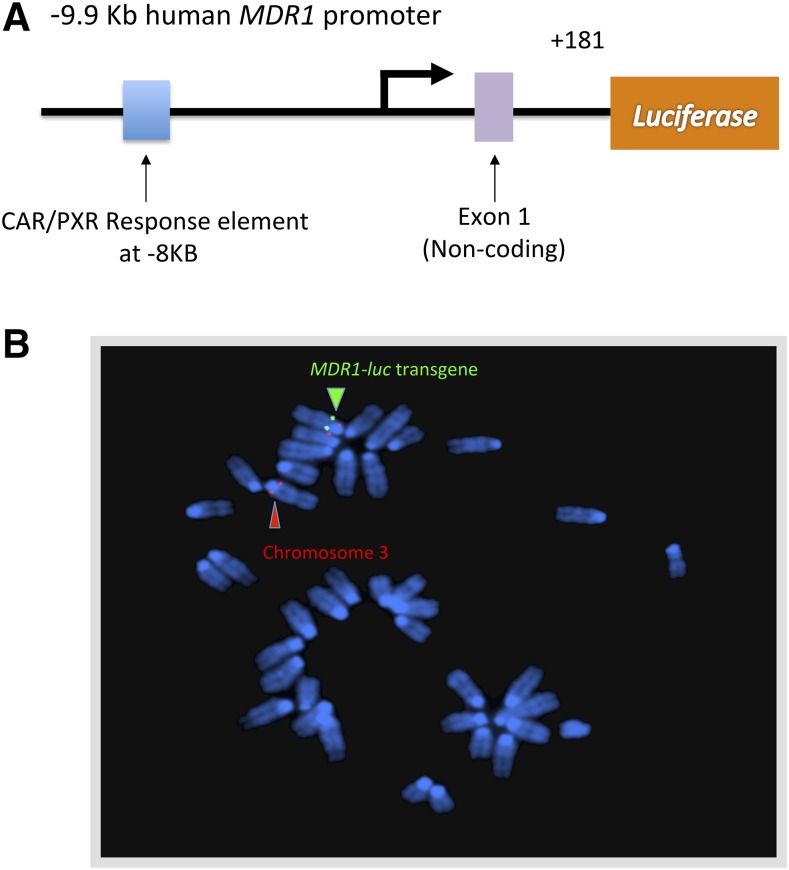

We developed MDR1-luc mouse lines containing ∼10 kb of 5′-flanking human MDR1 sequence directing expression of luciferase (Fig. 1A). After zygote microinjection and implantation, we identified multiple founder lines based on PCR screening and mouse tail luminescence. Two founder lines showed luciferase expression in brain and spine and one of these transgenic lines was selected for this study. We performed fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of MDR1-luc in heterozygous transgenic mice. The MDR1-luc mice had insertion of the transgene at a single location on chromosome 3 (Fig. 1B) and it was observed in all metaphase spreads examined from this line. PCR analysis of genomic DNA from the transgenic line with primers covering 9766 bp of the human MDR1 promoter confirmed that the entire promoter had inserted into the mouse genome.

Fig. 1.

MDR1-luc transgene. (A) Map of the MDR1-luc transgene. (B) Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of heterozygous MDR1-luc mouse lung fibroblast metaphase chromosomes with the MDR1-luc transgene probe (green) and a biotinylated chromosome 3 centromere specific probe (red) localizing the MDR1-luc transgene insertion to band 3A to 3B on chromosome 3.

MDR1-Luc Is Inducible in the Head and Spine of Reporter Mice by Activators of CAR, PXR, and GCR, and the Bcrp/Abcg2 Inhibitor, Elacridar, Further Increases Brain Bioluminescence.

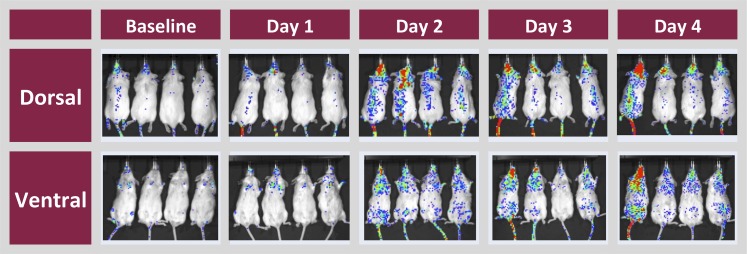

In vivo dorsal and ventral imaging of transgenic mice showed that the highest basal level of luciferase activity was in the head region and in some mice along the spine (Fig. 2). The MDR1-luc construct contains the regulatory cluster of nuclear response elements (−7864 to −7817 bp relative to the transcription start site of the human MDR1 gene) (Geick et al., 2001). Since Pgp is induced at the BBB by CAR activators (Bauer et al., 2004), mice were treated with the potent CAR agonist 1,4-bis[2(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benezene (Tzameli et al., 2000). Relative to baseline luciferase activity, there was a time-dependent induction of luminescence in the brain and spine. This pattern demonstrated that the human MDR1 5′-flanking sequence was sufficient to direct CNS expression of the luciferase reporter.

Fig. 2.

Induction of MDR1-luc in the head and spinal region of reporter mice by 1,4-bis[2(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benezene (TCPOBOP). MDR1-luc mice were treated daily with TCPOBOP and bioluminescence images were captured ventrally and dorsally 24 hours after each dose on four consecutive days. Red indicates the highest expression of MDR1-luc in each image.

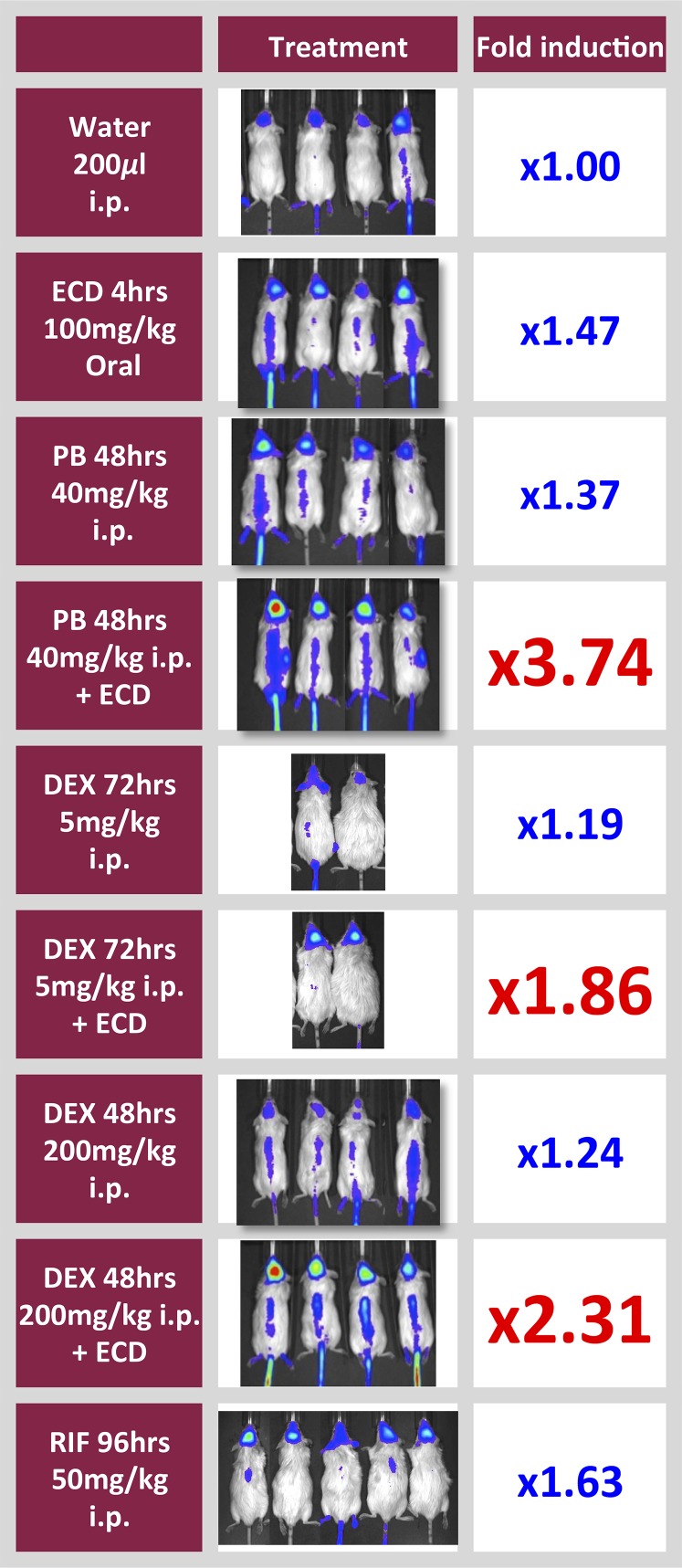

We next tested whether human MDR1 transcription was induced by other drugs demonstrated to increase Pgp in the brains of mice in vivo (Bauer et al., 2004; Narang et al., 2008). Treatment with phenobarbital (CAR activator) and with dexamethasone (GCR and PXR activators) increased MDR1-luc transcription in brains of the transgenic mice (Fig. 3). Since D-luciferin is a substrate of Bcrp (Zhang et al., 2007), a transporter that can limit brain availability of D-luciferin at the BBB (Bakhsheshian et al., 2013), we treated mice with an oral dose of elacridar (100 mg/kg) for 4 hours in order to maximize the brain-to-plasma concentration (Sane et al., 2012). Elacridar increased the total MDR1-luc bioluminescent signal up to 2-fold in vehicle- and drug-treated mice (Fig. 4); however, it did not change the regional pattern of MDR1-luc expression in the brain and spine of any mice. Elacridar’s effect appears to be due to inhibition of Bcrp, and not induction of Pgp, because the 4 hour treatment with elacridar failed to activate PXR and increase Pgp in an in vitro test system (unpublished observation).

Fig. 3.

Induction of MDR1-luc by PXR, CAR, and GCR agonists in reporter mice, and enhanced bioluminescence by elacridar. Mice received i.p. injections of vehicle (water), dexamethasone (DEX), or phenobarbital (PB) for 5 hours. Some mice also received oral gavage of elacridar (ECD) for 4 hours. Luciferase activity was optically measured in vivo at baseline and after drug treatment. Fold induction represents the change in photons in the brain region collected after 5 hours of drug treatment divided by the photons at time zero in the same animals and is given as the mean value of four animals/group.

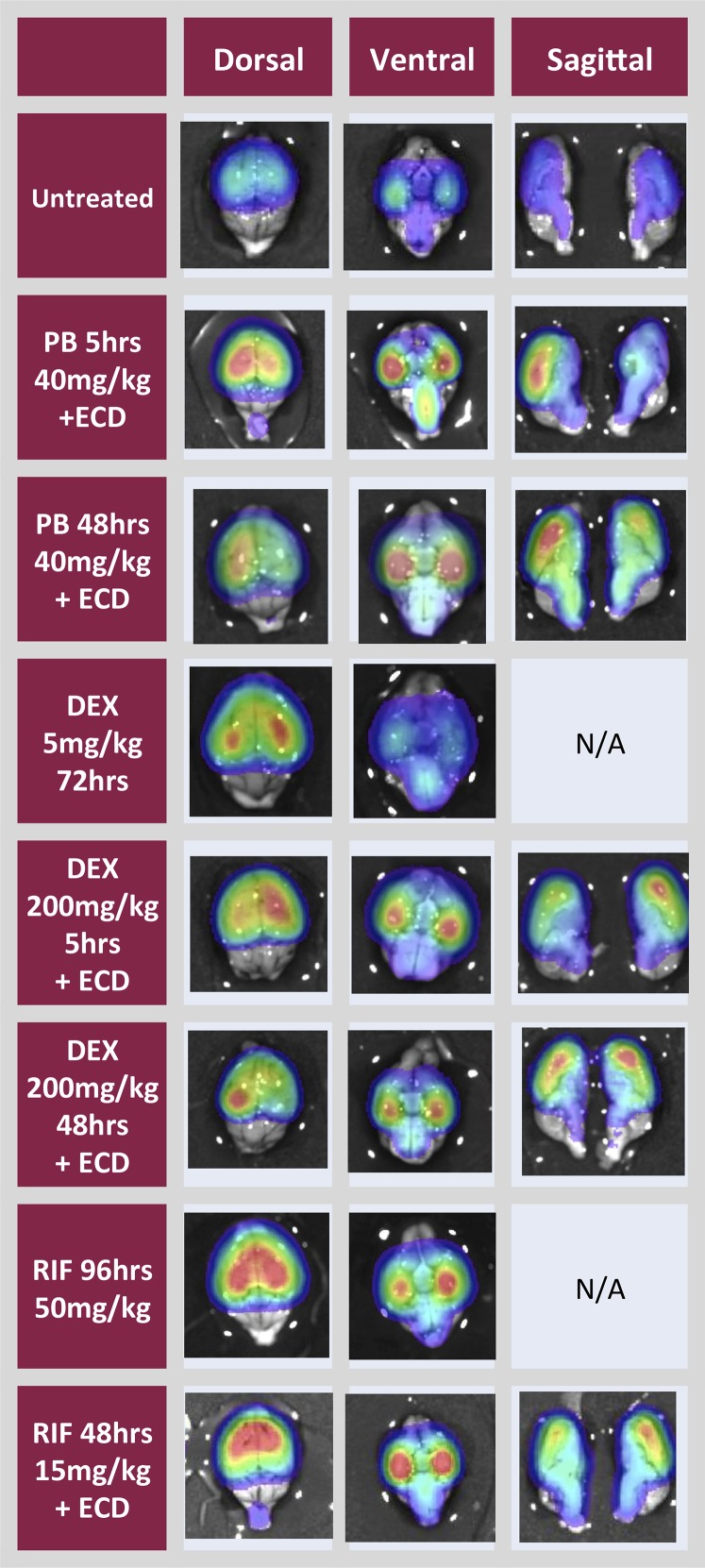

Fig. 4.

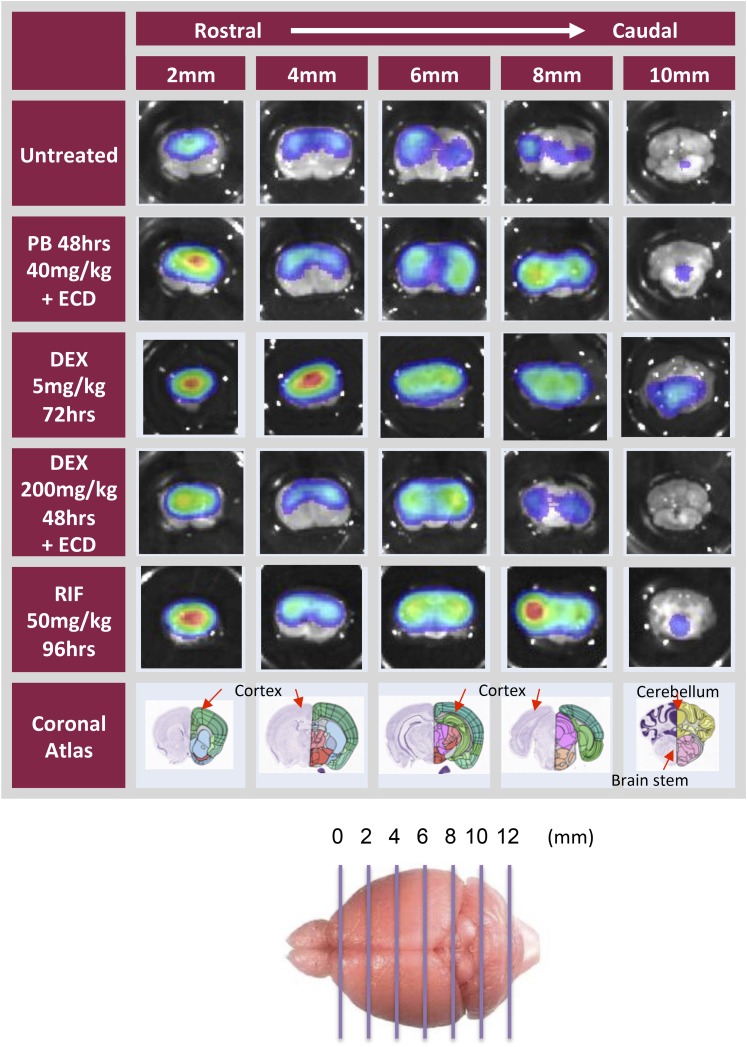

Ex vivo analysis of brains from MDR1-luc mice treated with inducers. Mice received i.p. injections of dexamethasone (DEX), phenobarbital (PB), or rifampicin (RIF) for 5 hours or every 24 hours for two consecutive days. Some mice also received oral gavage of elacridar (ECD) for the last 4 hours. Mice were injected with luciferin. Brains were removed, placed in luciferin solution, and then bioluminescence was optically imaged from the dorsal or ventral plane or in brain sagittal sections.

Brain Localization of the Human MDR1-Luc Signal versus Mouse Pgp by Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

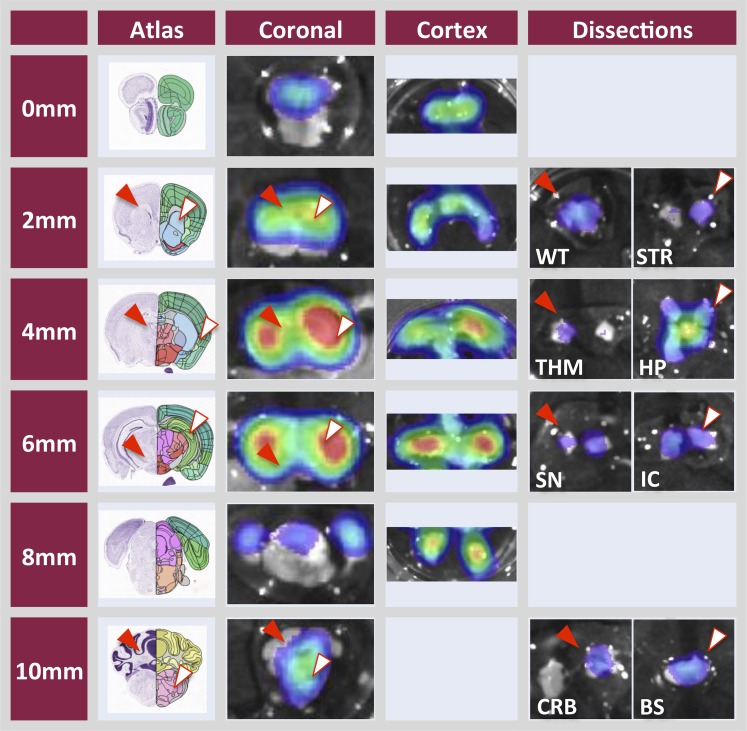

Brains from the MDR1-luc mice imaged in vivo were excised and imaged dorsally, ventrally, and sagitally (Fig. 4), and in serial coronal slices (Fig. 5), to further localize regional distribution of MDR1-luc bioluminescence. The luciferase distribution pattern was unique in the MDR1-luc model compared with other transgenic reporter mice such as androgen receptor element–luciferase mice (Dart et al., 2013), estrogen receptor element–luciferase mice (Stell et al., 2008), and tyrosine hydroxylase promoter–luciferase mice (Dodd et al., 2011). While the intensity of MDR1 transcription increased with various inducers, the distribution pattern of luciferase signal throughout the brain was similar, regardless of inducer. All chemicals increased MDR1 transcription to a greater extent in the cortex compared with the cerebellum. The coronal slices were further dissected and the luciferase signal was higher in the cortex versus cerebellum and was expressed in the white matter, thalamus, striatum, hippocampus, substantia nigra, brain stem, and internal capsule (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Ex vivo analysis of brains from MDR1-luc mice treated with inducers shows regional differences in transcriptional activity. Mice were treated with drugs, as indicted in the Fig. 4 legend, or with rifampicin (RIF) every 24 hours for four consecutive days, Mice injected with luciferin. Brains were immediately removed, sliced coronally (2 mm thickness), placed in a luciferin solution, and then bioluminescence imaged. The corresponding brain coronal image from the Allen Brain Atlas (http://www.brain-map.org) is included for reference to anatomic regions.

Fig. 6.

Ex vivo analysis of brains from MDR1-luc mice treated with inducers shows regional differences in transcriptional activity. Mice were treated with phenobarbital for 48 hours and elacridar, as indicated in the Fig 4 legend, and injected with luciferin. Brains were removed, sliced coronally (2 mm thickness), and further microdissected into nine regions (cortex; WT, white matter; STR, striatum; THM, thalamus; HP, hippocampus; SN, substantia nigra; IC, internal capsule; CRB, cerebellum; and BS, brain stem). The corresponding brain coronal image from the Allen Brain Atlas (http://www.brain-map.org) is included for reference to anatomic regions.

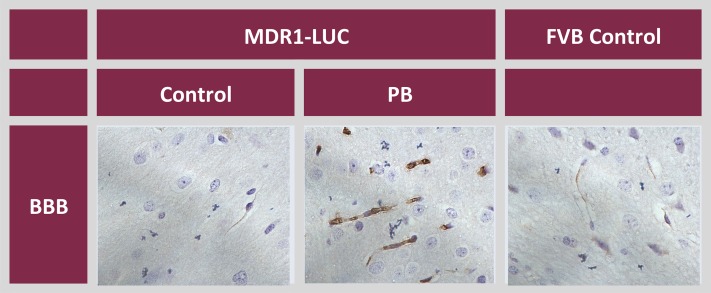

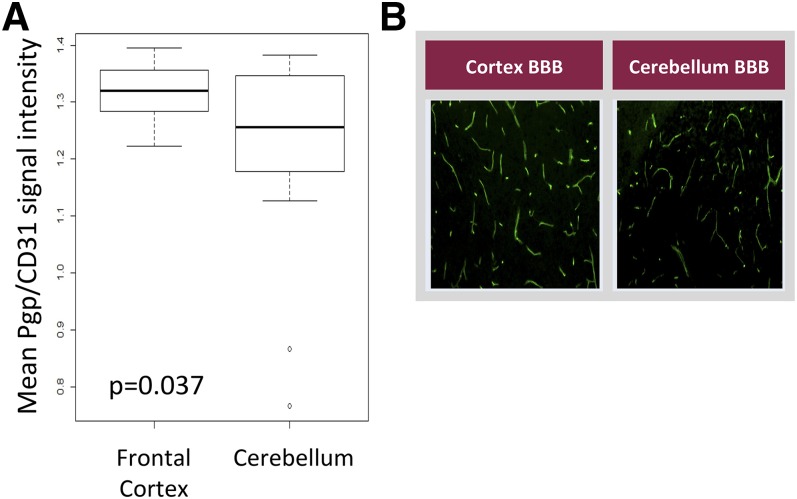

Brain tissue was processed for colorimetric IHC using an anti-luciferase antibody. The luciferase signal was localized to the BBB of vehicle-treated MDR1-luc mice, and was induced in the endothelial cells of capillaries of phenobarbital-treated MDR1-luc mice (Fig. 7). To determine whether mouse Pgp showed a similar regional pattern of brain expression in these same mice, MDR1-luc brain tissue was processed by fluorescent IHC using anti-Pgp and anti-CD31 (a vessel endothelial specific marker) antibodies and the fluorescent signal intensity was quantified. Consistent with the regional variation in MDR1-luc transcription, the mean mouse BBB Pgp signal, normalized to the CD31 signal, was higher in the frontal cortex compared with the cerebellum (Fig. 8). Regional differences in mouse brain local blood flow rates, brain capillary density, perfusion rate, and Pgp activity have been reported. Local cerebral blood flow was reported to be 1.65- to 1.82-fold greater in regions of brain cortex versus cerebellum (Otsuka et al., 1991; Zhao and Pollack, 2009). Thus, the regional differences in MDR1-luc reporter activity documented by photon imaging appear to mirror regional differences reported in blood flow, capillary density, and Pgp expression (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Luciferase expression in the brains of MDR1-luc mice. Immunostaining of luciferase (brown) in paraffin sections from the brains of FVB control mice and MDR1-luc mice treated with vehicle (control) or phenobarbital (PB) + elacridar, as described in the Fig. 5 legend, and images were captured at 63×. Luciferase immunostaining in the BBB is shown.

Fig. 8.

Regional heterogeneity in mouse brain Pgp expression and capillary density. (A) MDR1-luc mouse brains were analyzed by dual fluorescent IHC for mouse Pgp and CD31, the fluorescent signals were quantitated, and the mean intensity of Pgp was normalized to CD31 in the frontal cortex and cerebellum. Box plots indicate second and third quartiles. The bold line within the box represents the median and the whiskers represent the range after excluding the outliers. (B) Fluorescent immunostaining of BBB Pgp in C57BL/6 mouse brain in the cortex and cerebellum.

Discussion

A transgenic mouse was developed containing ∼10 kb of the 5′-regulatory region of human MDR1 driving a luciferase reporter in FVB mice in order to study the regulation of human BBB MDR1. This humanized model allowed real-time monitoring of MDR1 transcriptional activity throughout the mouse brain using the luciferase reporter, repeated measurements on the same animal (as opposed to sacrifice at specific time points), rapid detection of perturbations to gene expression, and characterization of the in vivo response. MDR1 brain and spine transcription increased following treatment with PXR, CAR, and GCR activators. Ex vivo luciferase immunostaining of brain tissue confirmed that MDR1 transcriptional activity was localized to vessel capillary endothelial cells. Thus, the MDR1-luc mouse offers an in vivo model to noninvasively monitor MDR1 regulation, both quantitatively and spatially.

This Study also Confirmed that a Bcrp Inhibitor Could Enhance Optimal Imaging of a Luciferase Reporter Gene in Mouse Brain, Presumably by Enhancing D-Luciferin Brain Bioavailability.

The brain penetration of 14C-D-luciferin in mice has been previously shown to be very low (Berger et al., 2008), which is consistent with the finding that luciferin is a Bcrp substrate (Zhang et al., 2007). Indeed, treatment with Bcrp inhibitors enhanced D-luciferin brain penetration of a low dose of D-luciferin (18 mg/kg) (Bakhsheshian et al., 2013), suggesting BBB Bcrp can limit brain availability of D-luciferin. At the D-luciferin concentrations used in most studies (and this one) (i.p. 240 mg/kg), luciferin can clearly penetrate the BBB as evidenced by MDR1-luc brain signals, even without a Bcrp blocker. However, oral elacridar pretreatment enhanced the brain luminescence, suggesting BBB Bcrp still limits some D-luciferin brain penetration, even at the high doses used here.

Our data show that the MDR1-luc signal was not uniformly distributed in mouse brain and was consistently higher in the cortex versus cerebellum in both untreated and treated mice. In addition, quantitative IHC analysis found the mean Pgp expression in mouse brain was significantly higher in the cortex compared with the cerebellum (Fig. 8). These results are consistent with several lines of evidence that Pgp activity shows regional distribution in the brain. First, Zhao and Pollack (2009) previously performed in situ brain perfusion of Pgp substrates in Pgp wild-type and knockout mice and found that the rate of regional perfusion flow and the Pgp efflux activity were directly proportional to the local capillary density in mouse brain. For example, pons, medulla, and cerebellum had the lowest vascular volume and functional flow rate, lowest blood perfusion flow rate, and lowest Pgp efflux ratio. Conversely, colliculi, thalamus, and parietal cortex had the highest vascular volume and functional flow rate and the highest Pgp efflux ratio. Second, some animal studies with positron emission tomography imaging have reported that Pgp inhibition increases substrate penetration to the greatest extent in the cerebellum (Zoghbi et al., 2008) and to the least extent in the frontal cortex. This result is interpreted to mean that Pgp function is lower in the cerebellum versus the cortex, which results in a greater effect of the Pgp inhibitor on Pgp function in the cerebellum versus the cortex. Hence, the regionality of MDR1-luc expression is consistent with the literature reports on regionality in Pgp-mediated efflux, which also has potential pharmacological implications, for example, since opioid receptors (targets of Pgp opioid substrates) are also concentrated in the thalamus and cortex regions (Inturrisi, 2002).

We Recognize that the Regional Patterns of MDR1-Luc Activity May Not Simply Be Due to Heterogeneity in Its Expression.

First, regional blood flow differences would also result in regional differences in local D-luciferin substrate delivery/distribution, and this could very well affect luminescence intensity. Hence, the brain regions with the largest vascular volume (cortex > cerebellum) would correspondingly have the highest perfusion concentration of D-luciferin. Thus, the heterogeneity in Pgp expression could be due both to the local capillary density (cortex > cerebellum) equaling a higher expression level of Pgp and to the higher blood flow and delivery/exposure of D-luciferin. Similarly, we cannot confirm that the MDR1 induction potential is not affected by the distribution of chemicals at the site of induction because we did not measure the regional concentration of each inducer. However, since cotreatment with the Pgp/Bcrp dual inhibitor elacridar + Pgp substrates did not change the distribution pattern of the MDR1-luc signal for any of the drugs (it only changed the magnitude of induction), this suggests that the luciferase distribution pattern reflects regional differences in MDR1 transcription.

Understanding Whether a Drug Is an Inducer of Human MDR1 is Important for Predicting Drug-Drug Interactions.

The pharmacodynamic consequence of inducing BBB Pgp is predicted to be tightening of the BBB drug barrier (Miller et al., 2008), and decreased brain exposure to Pgp substrates. Although induction of Pgp has been shown in the brains of some animal models following drug or chemical treatment, there is currently no in vivo model to predict induction of human MDR1 transcription in the brain. Equally important, because the in vitro Pgp induction models are not well understood, the current Food and Drug Administration guidance on evaluating Pgp induction potential of a new chemical entity is based not on direct evaluation of whether a drug induces Pgp but rather on whether it induces CYP3A (Zhang et al., 2009). If the drug is a CYP3A inducer, then further testing for Pgp induction in vivo is warranted. However, this advice is complicated by examples of tissue and species differences in induction of CYP3A and MDR1 (Schuetz et al., 1996a; Hartley et al., 2004). Moreover, the human BBB cells culture model has lost MDR1 regulation (Dauchy et al., 2009). In addition, it is desirable to determine if induction of Pgp actually occurs in the brain in vivo because of the added complication that the inducer has to effectively penetrate the BBB drug transport barrier. Indeed, rifampin, phenobarbital, and dexamethasone are all reported Pgp substrates (Schinkel et al., 1995; Schuetz et al., 1996b; Luna-Tortós et al., 2008). Nevertheless, at the drug exposure levels used in these studies, each of these drugs was clearly able to sufficiently penetrate the brain endothelial cells to induce MDR1. Hence, an in vivo model was clearly needed for further assessment of MDR1 regulation in the brain in vivo.

It Is Important to Understand Regulation of MDR1 Because Basic Mechanistic Understanding of How Brain Pgp Is Regulated by Drugs, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress and in Disease States Is Lacking (Miller, 2010).

Ex vivo analysis of Pgp in rodent brain tissue found that BBB Pgp is induced by seizures (van Vliet et al., 2007) and in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Jablonski et al., 2012), and that phenobarbital induced Pgp only in the hippocampus of epileptic rats (van Vliet et al., 2007) (a phenobarbital induction pattern strikingly different from what we observed in MDR1-luc mice). MDR1-luc mice would permit in vivo analysis of the temporal effects of these disease states and their treatments on regional human MDR1 transcription. Understanding whether human MDR1-luc could be induced in vivo is also of potential interest in modulation of Alzheimer’s disease. It was previously shown that Pgp could efflux amyloid-β peptide from the brain (Cirrito et al., 2005); hence, that modulation of Pgp activity might directly influence progression of amyloid-β pathology. Our results demonstrate that brain Pgp can be induced by a variety of drugs including rifampin, which intriguingly has previously been shown to slow the decline of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s (Loeb et al., 2004), potentially through induction of MDR1.

MDR1-Luc Mice Might Be of Value to Identify Chemicals that Down-Regulate MDR1 Transcription at the BBB and Enhance Brain Exposure of Pgp Substrates.

Attempts to block BBB Pgp and enhance drug brain delivery have been largely unsuccessful, making different approaches, such as modulating Pgp expression, important alternative strategies (Miller, 2010). Indeed, there has been limited success in inhibiting BBB Pgp efflux in humans, primarily due to the inability to achieve unbound systemic inhibitor concentrations sufficient to elicit appreciable inhibition (Kalvass et al., 2013). Although not tested in this study, one alternative approach would be to screen chemical libraries in order to identify chemicals capable of down-regulating MDR-luc transcription in vitro; in theory, these chemicals could be rapidly evaluated for their potential to regulate expression of brain MDR1-luc in whole animals.

The application of this MDR1-luc model to predict regulation of human Pgp still has challenges, including species differences in the interaction of compounds with mouse versus human PXR and in pathways of metabolism or BBB transport of drugs. However, interbreeding the MDR1-luc model with mice humanized for nuclear hormone receptors, CYPs, or drug transporters (Scheer and Roland Wolf, 2013; Scheer and Wolf, 2014) would potentially improve the utility and predictability of this in vivo model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Balasubramanian Poonkuzhali for PCR analysis of the MDR1 promoter in genomic DNA from the MDR1-luc transgenic line; Dr. Lubin Lan for some of the MDR1-luc imaging; Dr. Michael Taylor’s laboratory for stereoscope assistance; and Dr. Richard Smeyne’s laboratory for mouse brain microdissection assistance. The authors thank the following people for expert technical assistance at the shared resource facilities at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital: Dr. John Raucci (Transgenic Animal Core); Cheryl Winters (Animal Imaging Center); Dr. Victoria Frohlich and Jennifer Peters (Cell and Tissue Imaging Center); and Dr. Jill Lahti for fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis (Cancer Center Core Cytogenetics Laboratory).

Abbreviations

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- bp

base pair

- CAR

constitutive androstane receptor

- CNS

central nervous system

- FVB

Friend virus B

- GCR

glucocorticoid receptor

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MLPA

multiplex ligation-dependent probe assay

- nt

nucleotide

- PBST

phosphate-buffered saline with 0.3% Triton X-100

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- Pgp

P-glycoprotein

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- SALSA

Selective Adaptor Ligation, Selective Amplification

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Schuetz, Yasuda, Cline.

Conducted experiments: Yasuda, Cline, Lin, Scheib.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Thirumaran, Kim.

Performed data analysis: Schuetz, Yasuda, Cline, Chaudhry.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Schuetz, Yasuda, Cline, Scheib, Ganguly, Thirumaran.

Footnotes

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medicine [Grant R01 GM60346]; the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA21765]; and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at dmd.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Bakhsheshian J, Wei BR, Chang KE, Shukla S, Ambudkar SV, Simpson RM, Gottesman MM, Hall MD. (2013) Bioluminescent imaging of drug efflux at the blood-brain barrier mediated by the transporter ABCG2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:20801–20806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer B, Hartz AM, Fricker G, Miller DS. (2004) Pregnane X receptor up-regulation of P-glycoprotein expression and transport function at the blood-brain barrier. Mol Pharmacol 66:413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger F, Paulmurugan R, Bhaumik S, Gambhir SS. (2008) Uptake kinetics and biodistribution of 14C-D-luciferin—a radiolabeled substrate for the firefly luciferase catalyzed bioluminescence reaction: impact on bioluminescence based reporter gene imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 35:2275–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos CR, Schröter C, Wang X, Miller DS. (2012) ABC transporter function and regulation at the blood-spinal cord barrier. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 32:1559–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, Deane R, Fagan AM, Spinner ML, Parsadanian M, Finn MB, Jiang H, Prior JL, Sagare A, Bales KR, et al. (2005) P-glycoprotein deficiency at the blood-brain barrier increases amyloid-β deposition in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. J Clin Invest 115:3285–3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart DA, Waxman J, Aboagye EO, Bevan CL. (2013) Visualising androgen receptor activity in male and female mice. PLoS One 8:e71694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauchy S, Miller F, Couraud PO, Weaver RJ, Weksler B, Romero IA, Scherrmann JM, De Waziers I, Declèves X. (2009) Expression and transcriptional regulation of ABC transporters and cytochromes P450 in hCMEC/D3 human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol 77:897–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd KW, Burns TC, Wiesner SM, Kudishevich E, Schomberg DT, Jung BW, Kim JE, Ohlfest JR, Low WC. (2011) Transgenic mice expressing luciferase under a 4.5 kb tyrosine hydroxylase promoter. Cureus 3:e34. [Google Scholar]

- Geick A, Eichelbaum M, Burk O. (2001) Nuclear receptor response elements mediate induction of intestinal MDR1 by rifampin. J Biol Chem 276:14581–14587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L, Chen J, Synold TW, Forman BM, Kane SE. (2013) Bioimaging real-time PXR-dependent mdr1a gene regulation in mdr1a.fLUC reporter mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 345:438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L, Tsark WM, Brown DA, Blanchard S, Synold TW, Kane SE. (2009) A new model for studying tissue-specific mdr1a gene expression in vivo by live imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:5394–5399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley DP, Dai X, He YD, Carlini EJ, Wang B, Huskey SE, Ulrich RG, Rushmore TH, Evers R, Evans DC. (2004) Activators of the rat pregnane X receptor differentially modulate hepatic and intestinal gene expression. Mol Pharmacol 65:1159–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inturrisi CE. (2002) Clinical pharmacology of opioids for pain. Clin J Pain 18 (Suppl 4):S3–S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski MR, Jacob DA, Campos C, Miller DS, Maragakis NJ, Pasinelli P, Trotti D. (2012) Selective increase of two ABC drug efflux transporters at the blood-spinal cord barrier suggests induced pharmacoresistance in ALS. Neurobiol Dis 47:194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalvass JC, Polli JW, Bourdet DL, Feng B, Huang SM, Liu X, Smith QR, Zhang LK, Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, International Transporter Consortium (2013) Why clinical modulation of efflux transport at the human blood-brain barrier is unlikely: the ITC evidence-based position. Clin Pharmacol Ther 94:80–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski P, Lin M, Meikle L, Kwiatkowski DJ. (2007) Robust method for distinguishing heterozygous from homozygous transgenic alleles by multiplex ligation-dependent probe assay. Biotechniques 42:584–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb MB, Molloy DW, Smieja M, Standish T, Goldsmith CH, Mahony J, Smith S, Borrie M, Decoteau E, Davidson W, et al. (2004) A randomized, controlled trial of doxycycline and rifampin for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 52:381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna-Tortós C, Fedrowitz M, Löscher W. (2008) Several major antiepileptic drugs are substrates for human P-glycoprotein. Neuropharmacology 55:1364–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DS. (2010) Regulation of P-glycoprotein and other ABC drug transporters at the blood-brain barrier. Trends Pharmacol Sci 31:246–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DS, Bauer B, Hartz AM. (2008) Modulation of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier: opportunities to improve central nervous system pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev 60:196–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narang VS, Fraga C, Kumar N, Shen J, Throm S, Stewart CF, Waters CM. (2008) Dexamethasone increases expression and activity of multidrug resistance transporters at the rat blood-brain barrier. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295:C440–C450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka T, Wei L, Acuff VR, Shimizu A, Pettigrew KD, Patlak CS, Fenstermacher JD. (1991) Variation in local cerebral blood flow response to high-dose pentobarbital sodium in the rat. Am J Physiol 261:H110–H120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sane R, Agarwal S, Elmquist WF. (2012) Brain distribution and bioavailability of elacridar after different routes of administration in the mouse. Drug Metab Dispos 40:1612–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer N, Roland Wolf C. (2013) Xenobiotic receptor humanized mice and their utility. Drug Metab Rev 45:110–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer N, Wolf CR. (2014) Genetically humanized mouse models of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters and their applications. Xenobiotica 44:96–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinkel AH, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, Mol CA, Borst P. (1995) Absence of the mdr1a P-Glycoprotein in mice affects tissue distribution and pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone, digoxin, and cyclosporin A. J Clin Invest 96:1698–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz E, Lan L, Yasuda K, Kim R, Kocarek TA, Schuetz J, Strom S. (2002) Development of a real-time in vivo transcription assay: application reveals pregnane X receptor-mediated induction of CYP3A4 by cancer chemotherapeutic agents. Mol Pharmacol 62:439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz EG, Beck WT, Schuetz JD. (1996a) Modulators and substrates of P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P4503A coordinately up-regulate these proteins in human colon carcinoma cells. Mol Pharmacol 49:311–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz EG, Schinkel AH, Relling MV, Schuetz JD. (1996b) P-glycoprotein: a major determinant of rifampicin-inducible expression of cytochrome P4503A in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:4001–4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stell A, Belcredito S, Ciana P, Maggi A. (2008) Molecular imaging provides novel insights on estrogen receptor activity in mouse brain. Mol Imaging 7:283–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzameli I, Pissios P, Schuetz EG, Moore DD. (2000) The xenobiotic compound 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene is an agonist ligand for the nuclear receptor CAR. Mol Cell Biol 20:2951–2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet EA, van Schaik R, Edelbroek PM, Voskuyl RA, Redeker S, Aronica E, Wadman WJ, Gorter JA. (2007) Region-specific overexpression of P-glycoprotein at the blood-brain barrier affects brain uptake of phenytoin in epileptic rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 322:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Campos CR, Peart JC, Smith LK, Boni JL, Cannon RE, Miller DS. (2014) Nrf2 upregulates ATP binding cassette transporter expression and activity at the blood-brain and blood-spinal cord barriers. J Neurosci 34:8585–8593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Sykes DB, Miller DS. (2010) Constitutive androstane receptor-mediated up-regulation of ATP-driven xenobiotic efflux transporters at the blood-brain barrier. Mol Pharmacol 78:376–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weksler B, Romero IA, Couraud PO. (2013) The hCMEC/D3 cell line as a model of the human blood brain barrier. Fluids Barriers CNS 10:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhang YD, Zhao P, Huang SM. (2009) Predicting drug-drug interactions: an FDA perspective. AAPS J 11:300–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Bressler JP, Neal J, Lal B, Bhang HE, Laterra J, Pomper MG. (2007) ABCG2/BCRP expression modulates D-luciferin based bioluminescence imaging. Cancer Res 67:9389–9397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Pollack GM. (2009) Regional differences in capillary density, perfusion rate, and P-glycoprotein activity: a quantitative analysis of regional drug exposure in the brain. Biochem Pharmacol 78:1052–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi SS, Liow JS, Yasuno F, Hong J, Tuan E, Lazarova N, Gladding RL, Pike VW, Innis RB. (2008) 11C-loperamide and its N-desmethyl radiometabolite are avid substrates for brain permeability-glycoprotein efflux. J Nucl Med 49:649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.