Abstract

BAG3 protein has been described as an anti-apoptotic and pro-autophagic factor in several neoplastic and normal cells. We previously demonstrated that BAG3 expression is elevated upon HIV-1 infection of glial and T lymphocyte cells. Among HIV-1 proteins, Tat is highly involved in regulating host cell response to viral infection. Therefore, we investigated the possible role of Tat protein in modulating BAG3 protein levels and the autophagic process itself. In this report, we show that transfection with Tat raises BAG3 levels in glioblastoma cells. Moreover, BAG3 silencing results in highly reducing Tat- induced levels of LC3-II and increasing the appearance of sub G0/G1 apoptotic cells, in keeping with the reported role of BAG3 in modulating the autophagy/apoptosis balance. These results demonstrate for the first time that Tat protein is able to stimulate autophagy through increasing BAG3 levels in human glial cells.

Keywords: autophagy, BAG3, glioblastoma, HIV-1, Tat

Abbreviations

- BAG3

Bcl-2-Associated Athanogene 3

- Tat

Trans-Activator of Transcription;

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3

Introduction

HIV-1 enters brain early during infection and resides primarily in a limited number of macrophages, microglial cells and astrocytes. Long-term survival of these cells, after the initial infection, renders them an important reservoir of the virus and is one of the main obstacles to eradication of HIV-1 from infected tissues, including brain.1 Apoptosis suppression and/or autophagy induction can contribute to mechanisms that sustain cell survival.2 Among proteins that regulate the interplay between apoptosis and autophagy there is BAG3. Indeed, BAG3 expression reportedly inhibits apoptosis and enhances autophagy in a number of cell types.3-5 We previously demonstrated an upregulation of BAG3 protein levels in glial and T lymphocyte cells upon HIV-1 infection.6-7 One of the HIV-1 proteins mostly involved in regulating host cell response to viral infection is represented by Tat, which is expressed early in the viral life cycle.8 Since BAG3 is upregulated during autophagy and the autophagic process results in a pro-survival effect, we investigated the possible involvement of Tat protein in enhancing BAG3 levels, thereby modulating the autophagy/apoptosis balance in glial cells.

Results

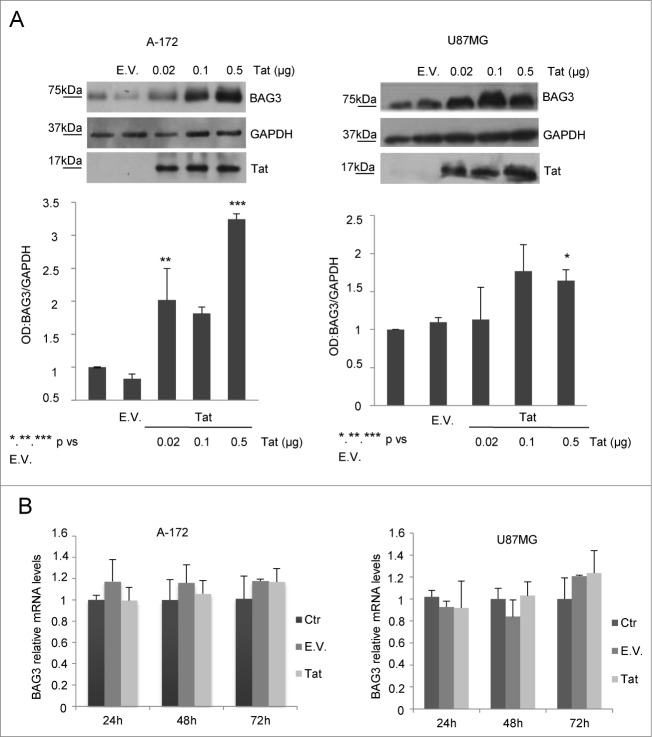

In order to analyze the possible activity of Tat protein in regulating BAG3 levels in glial cells, we transfected 2 human glioblastoma cell lines with increasing concentrations of a plasmid able to express Tat protein and verified BAG3 protein levels in transfected cells. We observed a significant increase of BAG3 protein amounts upon transfection both in U87MG and A-172 cells (Fig. 1A). However, by quantitative real-time RT-PCR, we did not find any significant changes in bag3 mRNA at different time points upon Tat expression in respect to controls (Fig. 1B). This result suggests that the enhancing effect of Tat protein on BAG3 levels is exerted at a post-transcriptional level.

Figure 1.

BAG3 protein levels increase in Tat- overexpressing cells. U87MG and A-172 glioblastoma cell lines were transfected with increasing concentrations of an HIV-1 Tat expressing plasmid or an empty vector. BAG3 protein expression levels were monitored using Western blot analysis (A), and BAG3 mRNA levels were analyzed using RT-PCR (B); the graphs depict mean levels (± SD), and data are representative of 3 independent experiments. *P = 0.05 to 0.01; **P = 0.01 to 0.001; ***P < 0.001.

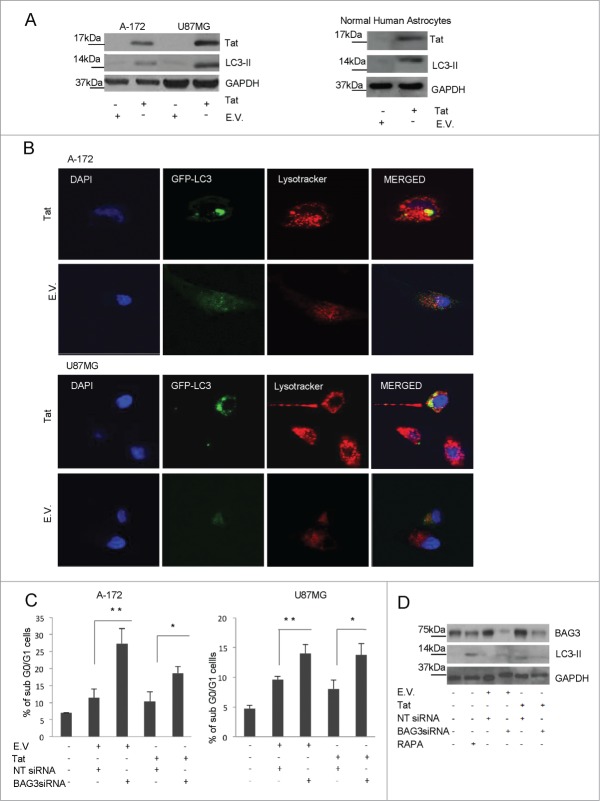

BAG3 was recently described as a mediator of autophagy and appears indeed involved in initiating autophagosome formation.3-5,9 We therefore analyzed whether enhancement of BAG3 levels by Tat protein was associated to a stimulation of the autophagic process. By western blot, we detected LC3-II presence in Tat-transfected cells. The induction of autophagy by Tat, was also confirmed in Normal Human Astrocytic (NHA) cells (Fig. 2A). Since autophagosomes are transient vescicles that deliver their cargo within minutes for lysosomal hydrolysis, their accumulation could result from their increased formation or from their decreased degradation.10,11 In order to verify if Tat induces or blocks autophagy, we analyzed the autophagic flux to lysosomes. In Tat containing cells, GFP- LC3 vescicles were found colocalized with lysosomes compartments, indicating that the increase in LC3-II is accompanied to autophagosomes degradation (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Autophagy activation in Tat-transfected cells. (A) U87MG, A-172 and NHA cells were transfected with a HIV-1 Tat- expressing plasmid or an empty vector. LC3-II levels were analyzed using Western blotting, and GAPDH levels were detected to monitor equal loading conditions. (B) A-172 and U87MG cells were transfected with a GFP-LC3 expressing plasmid in presence of a Tat- expressing plasmid or an empty vector as control. Lysotracker Deep Red was used for staining lysosomal compartments. Cells were then analyzed with a confocal microscope. Images were obtained from DAPI staining, GFP-LC3 and Lysotracker deep red fluorescence. Yellow region indicate co-localization. (C) U87MG and A-172 cells were plated at 30% of confluence, transfected with a BAG3siRNA or a non-targeted (NT) siRNA. After 72 h, cells were transfected with a Tat- expressing plasmid or with an empty vector as described above. Apoptotic cell death was analyzed by flow cytometry. Graph depicts mean ± SD percentage of sub-G0/G1 cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) A-172 were transfected with BAG3siRNA or NT siRNA as described above. Rapamycin- treated cells were used as a control of autophagy induction. LC3-II levels were analyzed by protein gel blotting. *P = 0.05 to 0.01; **P = 0.01 to 0.001; ***P < 0.001.

We then investigated the role of BAG3 in autophagy and apoptosis modulation in Tat-transfected cells. We detected low levels of apoptosis, measured as percentage of subG0/G1 elements, in Tat-transfected cells. On the other hand, such percentage was significantly enhanced by BAG3 silencing (Fig. 2C). Therefore, Tat-induced BAG3 appeared to downmodulate the apoptosis process. These results are in agreement with cell sensitization to apoptosis by BAG3-downmodulating agents in several cell systems.4,12-17 In parallel we verified the effect of BAG3 silencing on the induction of LC3-II by Tat. While in Tat- transfected cells, there was an increase in LC3-II levels, these were highly reduced in presence of BAG3 siRNA (Fig. 2D), indicating that BAG3 is required for LC3-II induction by Tat.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate for the first time that Tat protein is able to induce an increase in BAG3 levels. Furthermore, in agreement with the reported involvement of BAG3 in the autophagic process,3-5,9 Tat protein is shown to stimulate autophagy; this is, to the best of our knowledge, the first reported evidence of a pro-autophagy activity of Tat.

Tat- induced BAG3, has the double effect of downmodulating apoptosis and enhancing autophagy; this regulatory tie between the 2 processes can efficiently contribute to cell survival and could likely participate in the mechanisms by which HIV-1 establishes its cell reservoirs.

Material and Methods

Cell cultures and transfections

U87MG and A-172 glioblastoma cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen–Carlsbad, CA, USA) and penicillin/streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Normal human astrocytes (NHA) cell line was purchased from LONZA (Basel, Switzerland) and grown in AGM TM BulletKitTM (LONZA). Cells were plated at 40% of confluence and transfected with increasing concentrations (0.02, 0.1, 0.5 μg) of a pDC515 (PD-01–35, Microbix Biosystems Inc..) plasmid expressing full-length HIV-1 Tat or pDC515 empty vector. GFP-LC3 expressing vector was kindly provided by Dr.Cecconi.18,19 The bag3 siRNA (5′-AAGGUUCAGACCAUCUUGGAA-3′) and NTsiRNA (5′-CAGUCGCGUUUGCGACUGG- 3′) were synthesized by Eurofins Group. Cells were transfected with siRNAs at a final concentration of 200 nmol/L using TransFectin (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) by following manufacturer's protocol.

Western blot analysis and antibodies

Cells were collected, washed in PBS 1×, and resuspended in RIPA buffer (pH 8) (150 mmol/L NaCl [pH 8], 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% Na-Doc, and 0.1% SDS) and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) for 30 min on ice. The lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was used for Western blot analysis. Protein concentration was measured using the Bradford protein assay reagent using bovine serum albumin as standard. Twenty micrograms of protein extracts were resolved on 10–12% SDS–polyacrylamide gels using a mini-gel apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Nitrocellulose blots were blocked with 10% non-fat dried milk in Tris buffer saline Tween-20 (TBST) (20 mM Tris-HCl pH7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 0.01% Tween 20) and probed overnight at 4°C with appropriate dilutions of primary antibodies in 10% blocking solution or 5% bovine serum albumin. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated IgGs in blocking solution were used to detect specific proteins. Immunodetection was performed using chemiluminescent substrates, and was recorded using Hyperfilm ECL (both from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Amersham, UK). Anti-BAG3 antibody (rabbit polyclonal) was obtained from BIOUNIVERSA s.r.l. (Salerno, Italy), anti-HIV-1 Tat (REP0030) and anti-LC3-II (41085) antibodies were purchased respectively from DIATHEVA s.r.l (Fano, Italy) and Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA, US). To monitor equal loading conditions we used an anti-GAPDH antibody (sc-32233) obtained from Santa Cruz Biotecnologies (Santa Cruz, CA, US). Scanning densitometry of the bands was performed with an Image Scan (SnapScan 1212). The area under the curve related to each band was determined using Gimp2 software. Background was subtracted from the calculated values. Significance was determined by unpaired Student's t-test.

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

Cells were harvested after 24, 48 and 72 h; then total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) and digested with DNase (Invitrogen). One μg of RNA was then retrotranscribed using random examers and treated with RNaseA (Invitrogen). A quantitative RT-PCR assay was performed using the LightCycler 480 SYBR green I Master (Roche Diagnostics) with a Roche 480 LightCycler. BAG3 mRNA levels were expressed as a ratio to GAPDH mRNA levels; primers used were BAG3 FWD (5′-CAGGAGCAGCACGCCACTCC-3′), BAG3 REV (5′-TGGTCCAACTGGGCCTGGCT-3′), GAPDH FWD (5′-AGCCTCCCGCTTCGCTCTCT-3′), and GAPDH REV (5′-CCAGGCGCCCAATACGACCA -3′). Each sample was run in triplicate. Analysis of relative gene expression data was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.20

Confocal microscopy

Cells were cultured on coverslips in 6-well plates to 60–70% confluence and transfected with a GFP-LC3 expressing vector together with a Tat expressing vector or an empty vector. After 36 h of transfection, 50 nM Lysotracker Deep Red (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, US) was added to the medium. After 30 min, coverslips were washed in 1× PBS and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in 1× PBS for 30 min at room temperature, and then incubated for 10 min with 1× PBS, 0.1 M glycine and washed again in 1× PBS. Nuclei were visualized with a diluition 1:5000 of DAPI, 10 min at room temperature. After washing in distilled water, coverslips were then mounted on a slide with interspaces containing 47% (v/v) glycerol. Samples were analyzed using a Zeiss LSM confocal microscope. Images were acquired in sequential scan mode by using the same acquisitions parameters (laser intensities, gain photomultipliers, pinhole aperture, objective 63×, zoom 2) when comparing experimental and control material. For production of figures, brightness and contrast of images were adjusted by taking care to leave a light cellular fluorescence background for visual appreciation of the lowest fluorescence intensity features and to help comparison between the 2 experimental groups. Final figures were assembled using Adobe Photoshop 7 and Adobe Illustrator 10.

Apoptosis

The percentage of sub-G0/G1 cells was analyzed via propidium iodide incorporation into permeabilized cells, and flow cytometry was performed as described previously.12 Data were analyzed by unpaired Student's t-test using the Prism statistical program (GraphPad Software).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by US NIH (R01 MH086358–01A1).

References

- 1. Kramer-Hämmerle S, Rothenaigner I, Wolff H, Bell JE, Brack-Werner R. Cells of the central nervous system as targets and reservoirs of the human immunodeficiency virus. Virus Res 2005; 11:194-213; PMID:15885841; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubinstein AD, Kimchi A. Life in the balance—a mechanistic view of the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. J Cell Sci 2012; 125:5259-68; PMID:23377657; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.115865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Behl C. BAG3 and friends: co-chaperones in selective autophagy during aging and disease. Autophagy 2011; 7:795-8; PMID:21681022; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.7.7.15844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosati A, Graziano V, De Laurenzi V, Pascale M, Turco MC. BAG3: a multifaceted protein that regulates major cell pathways. Cell Death Dis 2011; 2:e141; PMID:21472004; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cddis.2011.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ulbricht A, Höhfeld J. Tension- induced autophagy: may the chaperone be with you. Autophagy 2013; 9:920-2; PMID:23518596; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.24213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosati A, Leone A, Del Valle L, Amini S, Khalili K, Turco MC. Evidence for BAG3 modulation of HIV-1 gene transcription. J Cell Physiol 2007; 210:676-83; PMID:17187345; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.20865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosati A, Khalili K, Deshmane SL, Radhakrishnan S, Pascale M, Turco MC, Marzullo L. BAG3 protein regulates caspase-3 activation in HIV-1-infected human primary microglial cells. J Cell Physiol 2009; 218:264-7; PMID:18821563; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.21604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abraham S, Sawaya BE, Safak M, Batuman O, Khalili K, Amini S. Regulation of MCP-1 gene transcription by Smads and HIV-1 Tat in human glial cells. Virology 2003; 309:196-202; PMID:12758167; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00112-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ulbricht A, Eppler FJ, Tapia VE, van der Ven PF, Hampe N, Hersch N, Vakeel P, Stadel D, Haas A, Saftig P, et al. Cellular mechanotrasnsduction relie on tension- induced and chaperone- assisted autophagy. Curr Biol 2013; 23:430-35; PMID:23434281; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 2012; 8:445-544; PMID:22966490; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.19496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gannagé M, Dormann D, Albrecht R, Dengjel J, Torossi T, Rämer PC, Lee M, Strowig T, Arrey F, Conenello G, et al. Matrix protein 2 of influenza A virus blocks autophagosome fusion with lysosomes. Cell Host Microbe 2009; 6:367-80; PMID:19837376; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chom.2009.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ammirante M, Rosati A, Arra C, Basile A, Falco A, Festa M, Pascale M, d'Avenia M, Marzullo L, Belisario MA, et al. IKK{gamma} protein is a target of BAG3 regulatory activity in human tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:7497-502; PMID:20368414; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0907696107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosati A, Bersani S, Tavano F, Dalla Pozza E, De Marco M, Palmieri M, De Laurenzi V, Franco R, Scognamiglio G, Palaia R, et al. Expression of the antiapoptotic protein BAG3 is a feature of pancreatic adenocarcinoma and its overexpression is associated with poorer survival. Am J Pathol 2012; 181:1524-29; PMID:22944597; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Falco A, Festa M, Basile A, Rosati A, Pascale M, Florenzano F, Nori SL, Nicolin V, Di Benedetto M, Vecchione ML, et al. BAG3 controls angiogenesis through regulation of ERK phosphorylation. Oncogene 2012; 31:5153-61; PMID:22310281; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2012.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Festa M, Del Valle L, Khalili K, Franco R, Scognamiglio G, Graziano V, De Laurenzi V, Turco MC, Rosati A. BAG3 protein is overexpressed in human glioblastoma and is a potential target for therapy. Am J Pathol 2011; 178:2504-12; PMID:21561597; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chiappetta G, Basile A, Arra C, Califano D, Pasquinelli R, Barbieri A, De Simone V, Rea D, Giudice A, Pezzullo L, et al. BAG3 down-modulation reduces anaplastic thyroid tumor growth by enhancing proteasome-mediated degradation of BRAF protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(1):E115-20; PMID:22072743; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/jc.2011-0484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosati A, Basile A, Falco A, d'Avenia M, Festa M, Graziano V, De Laurenzi V, Arra C, Pascale M, Turco MC. Role of BAG3 protein in leukemia cell survival and response to therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012; 1826:365-9; PMID:22710027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Morselli E, Criollo A, D'Amelio M, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Cecconi F, Tavernarakis N, Kroemer G. A dual role of p53 in the control of autophagy. Autophagy 2008; 4:810-4; PMID:18604159; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.6486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nazio F, Strappazzon F, Antonioli M, Bielli P, Cianfanelli V, Bordi M, Gretzmeier C, Dengjel J, Piacentini M, Fimia GM, et al. mTOR inhibits autophagy by controlling ULK1 ubiquitylation, self-association and function through AMBRA1 and TRAF6. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15:406-16; PMID:23524951; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 2001; 4:402-8; PMID:11846609; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]