Abstract

The high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) E7 oncogene abrogates DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint but the mechanism is not fully understood. The G1 kinase Cdk2 is activated in E7-expressing cells. However, whether Cdk2 is required for E7 to abrogate the G1 checkpoint is not known. Accumulating evidence implicates a role for the mitotic Cdk1 in G1/S phase transition in the absence of Cdk2. We therefore examined the expression and requirement of Cdk1 and Cdk2 in the G1 checkpoint abrogation in E7-expressing cells. Although both Cdk1 and Cdk2 were up-regulated in E7-expressing cells upon DNA damage, down-regulation of Cdk1 but not Cdk2 impairs the ability of E7 to abrogate the G1 checkpoint. Our study thus demonstrated an important role for Cdk1 in bypassing the G1 checkpoint in E7-expressing cells. To understand the mechanism by which E7 activates Cdk1, we examined the transcription factor B-Myb. Our studies demonstrated that downregulation of B-Myb reduced the steady-state level of Cdk1 and induced G1 arrest in E7-expressing cells upon DNA damage. In addition, it remains a mystery how E7 promotes cell cycle progression in the presence of Cdk inhibitor p21. As p21 binds Cdk1 with lower affinity than Cdk2, our results suggest a mechanism by which E7 bypasses the inhibitory effect of p21. Nonetheless, our studies demonstrated that p21 still possessed partial ability to arrest cells at G1 phase in E7-expressing cells. These studies shed light on mechanisms by which HPV E7 modulates cell cycle checkpoint.

Keywords: B-Myb, Cdk, checkpoint control, DNA damage, E7, G1 checkpoint, oncogene, papillomavirus

Abbreviations

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- Cdk

cyclin-dependent kinase

- PHKs

primary human keratinocytes

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) are small DNA viruses with a demonstrated tropism for the basal layer of the stratified squamous epithelia. Under physiological circumstances stratified epithelia exit from cell cycle and are destined toward terminal differentiation. However, HPV infection can alter epithelia differentiation. Human epithelial cells containing HPV type 16 (HPV-16), which is the cause of approximately 50% of cervical cancers worldwide, retain the ability to stratify but lose their ability to differentiate morphologically.1 HPV also promotes S-phase re-entry in differentiating keratinocytes.2 Hence, HPV can manipulate cell cycle by promoting the suprabasal cells entering into the cell cycle and retarding the differentiation process.

Cell cycle is controlled by multiple positive and negative regulators at several checkpoints.3,4 Abrogation of cell cycle checkpoint may lead to genomic instability.5 Cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) and their regulatory subunit cyclins play a positive role and act as a motor to drive cell cycle progression.4 For this, cyclins and Cdks have to counteract the effects from negative factors such as p21 and ensure DNA replication and mitosis. It has long been thought that Cdk2 is the major player and a master regulator at G1/S transition, while the mitotic Cdk1 is the main facilitator for G2/M transition. Surprisingly, several lines of evidence during the past decade indicate that Cdk2 is not essential for cell division.6-10 After depletion of Cdk2, cells including those from pRb-negative cervical cancer cell lines continue to proliferate.10 Cdk2 knockout mice are viable and essentially normal.11 In the absence of all three G1 Cdks (Cdk2, Cdk4 and Cdk6), Cdk1 compensates for their functions.5,7,12 However, a role for Cdk1 in the presence of Cdk2 at the G1 checkpoint has not been demonstrated.

E6 and E7 are the two main HPV encoded oncogenes. They are consistently expressed in HPV-positive cervical cancers.13 The HPV E7 gene encodes a small nuclear protein of about 100 amino acids. The oncogenic activities of E7 have been reflected in multiple biological assays.14 The expression of HPV E7 uncouples the processes of cellular proliferation and differentiation.15 E7 modulates cell cycle by different mechanisms from E6. For example, E6 targets p53 for degradation while E7 degrades pRb and releases E2F to turn on genes required for DNA replication (reviewed in).16 Under normal condition, DNA damage arrests cells in G1, prevents cells with damaged DNA from being multiplying and allows the cellular repair systems to fix damaged DNA. Although E7-expressing cells contain elevated steady-state level of p21,17 they can still bypass the G1 arrest induced by DNA damage.18 How E7 promotes cell cycle progression in the presence of p21 remains a mystery.

The Myb gene family consists of 3 members, namely A-, B- and C-Myb. They encode nucleoproteins that activate transcription. Although these 3 genes are highly homologous, their expression patterns are largely different. While the A- and C-Myb expressions are highly tissue-specific, the B-Myb is expressed in virtually all cells and tissues.19 B-Myb is an E2F-responsive gene and a component of the DREAM complex that promotes expression of genes during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle.20 Regulation of BALB/c 3T3 fibroblast proliferation by B-Myb is accompanied by selective activation of Cdk1.21 Furthermore, B-Myb interacts with the Cdk1 promoter, its knockdown inhibits the expression of Cdk1 as well as cyclin B1.22 Notably, ectopic expression of B-Myb bypasses p53-induced, p21-mediated G1 arrest.23 Multiple lines of evidence suggest that B-Myb plays an important role in HPV-associated carcinogenesis. The B-Myb gene expression is increased in cervical cancer.24,25 In HPV-16-positive oropharyngeal cancer cells, reduction of E6 and E7 expression correlates with decreased B-Myb expression.26 HPV E7 is able to activate the B-Myb promoter in C33A and primary human keratinocytes (PHKs) after transient transfection.27 E7-immortalized human keratinocytes show an increased transcription of B-Myb.28 Repression of E7 in cervical carcinoma cells repressed the expression of B-Myb.29 A functional interaction between HPV-16 E7 and B-Myb has been recently shown to activate both S- and M-phase genes.30 Nonetheless, how B-Myb contributes to HPV-associated carcinogenesis is not known.

In the present study, we investigated the mechanism by which HPV-16 E7 abrogates the G1 cell cycle checkpoint. We showed that in immortalized human epithelial cells, the expression of HPV-16 E7 efficiently overrides DNA damage-induced G1 arrest. Cdk1, instead of Cdk2, plays a key role in the G1/S transition in E7-expressing cells. B-Myb plays an important role in up-regulation of Cdk1 by E7 and abrogates the G1 checkpoint. p21 is partially inactivated by HPV E7.

Results

HPV-16 E7 abrogates DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint in immortalized human epithelial cells

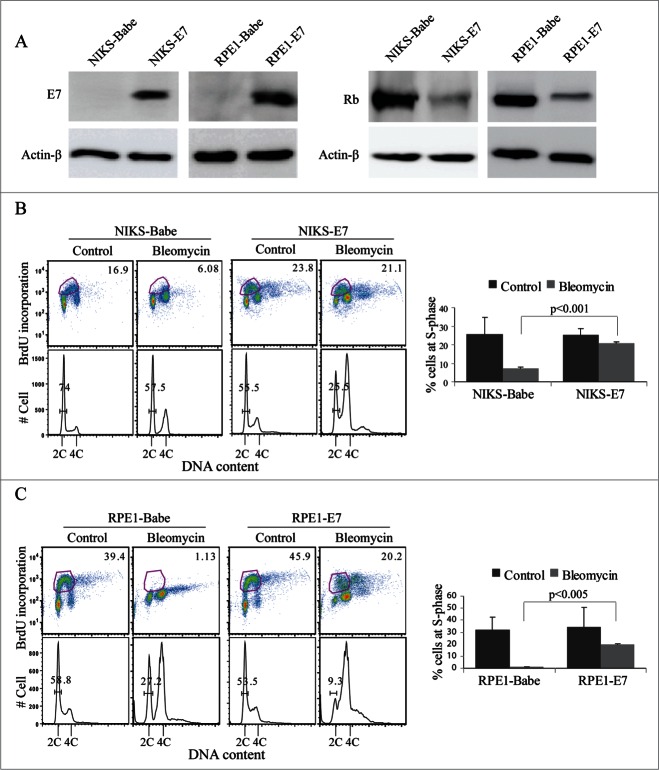

It is well-established that E7s from the high-risk HPV types abrogate the G1 checkpoint.14,31-33 We have also shown recently that PHKs expressing HPV-16 E7 bypass DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint.34,35 However, the mechanism underlying E7 abrogation of the G1 checkpoint is not fully understood. The availability of small interfering RNA (siRNA) makes it possible to identify molecules important for E7 to alleviate the G1 checkpoint. However, in our experimental conditions, the efficiency of transfection in PHKs is not satisfactory. Besides, PHKs arrest at G1 upon transfection. To avoid these issues, we used the hTERT-immortalized RPE1 cells that express HPV-16 E7.36 In addition, we established E7- expressing NIKS cells by retroviral-mediated infection. The expression of E7 and pRb in NIKS cells and RPE1 cells was assessed by Western blot (Fig. 1A). The results showed that E7 was expressed and pRb level was reduced in both cell types.

Figure 1.

HPV-16 E7 abrogates DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint in immortalized human epithelial cells. (A) Expression of E7 and pRb. The steady-state levels of E7 and pRb proteins in NIKS and RPE1 cells were determined by immunoblotting. Actin-β was used as a loading control. (B) E7 abrogates DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint in NIKS cells. HPV-16 E7-expressing and vector-containing NIKS cells were treated with bleomycin, labeled with BrdU, stained with anti-BrdU antibody, counterstained with PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry of BrdU staining profiles and histograms are shown (Left panel). The percent of BrdU-positive cells is indicated. Mean percent of BrdU-positive NIKS cells from 3 experiments are summarized (Right panel). Error bars reflect the standard deviations of the mean. (C) HPV 16 E7-expressing and vector control RPE1 cells were treated with bleomycin and analyzed as in (B). Representative flow cytometry of BrdU staining profiles and histograms are shown (Left panel). The percent of BrdU-positive cells is indicated. Mean percent of BrdU positive RPE1 cells from 2 experiments are summarized (Right panel). Error bars reflect the standard deviations of the mean.

To assess the integrity of G1 checkpoint in the E7-expressing immortalized epithelial cells, we treated cells with the DNA damaging agent and radiomimetic bleomycin.37 The treatment with DNA damage agent is biologically relevant as both E6 and E7 oncogenes from high-risk HPV types induce DNA damage.38-40 DNA damage could also result from spontaneous decay, replication errors and cellular metabolism.41 We then measured bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation in E7-expressing immortalized epithelial cells after treating with bleomycin. As shown in Figure 1B, although there was no marked difference in number of BrdU-positive cells between untreated NIKS Babe and E7 cells (Averages of 25.6% vs. 25.3%), upon bleomycin treatment the percentages of cells in S-phase between NIKS Babe and E7-expressing cells were significantly different (Averages of 7.0% vs. 20.6%, P < 0.001). While NIKS cells expressing HPV-16 E7 maintained a relatively higher number of cells undergoing replication upon bleomycin treatment, vector-containing NIKS cells showed significantly reduced BrdU incorporation. Similar results were obtained in the more efficiently proliferating RPE1 cells containing a retroviral vector or expressing HPV-16 E7 (Fig. 1C). These results demonstrated that E7 abrogated DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint in the immortalized epithelial cells.

Role of Cdks in abrogation of the G1 checkpoint by HPV E7

Cdk2 has been considered the master kinase for G1/S transition.42 Cdk2 activities are high in E7-expressing cells (Reviewed in).43 Previous studies have also demonstrated E7-expressing cells retained significant amount Cdk2 activity upon DNA damage44 (and references therein). However, these studies did not examine whether activated Cdk2 was required for E7 to abrogate the G1 checkpoint. On the other hand, accumulating evidence implicates a role for Cdk1 in G1/S phase transition. We therefore assessed the expression and requirement for Cdk1 and Cdk2 in E7-expressing cells.

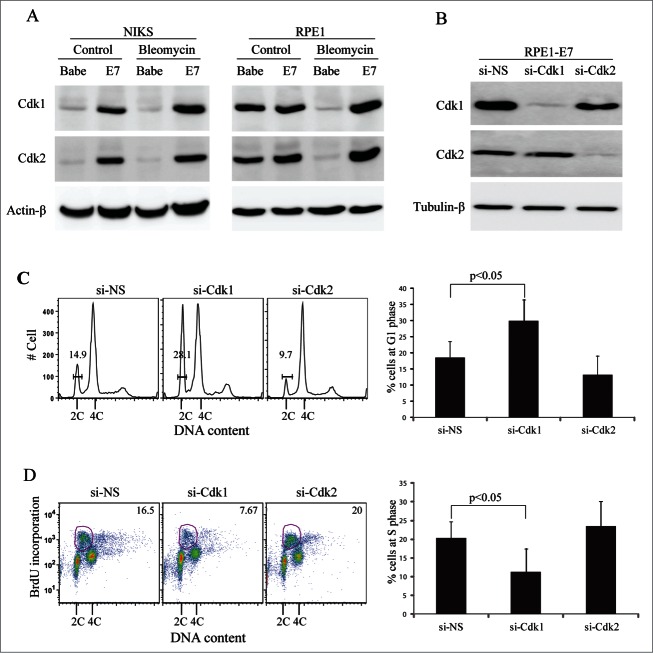

As shown in Fig. 2A (Left panel), both Cdk1 and Cdk2 levels were increased (More than 4-fold) in E7-expressing NIKS cells as compared with the vector control cells. Upon DNA damage, there was no significant change in the steady-state levels of Cdk1 and Cdk2 in these cells. As a result, the difference in Cdk levels between NIKS cells expressing E7 and the vector control cells remains similar (4-fold). Although there was no significant difference in Cdk1 and Cdk2 levels between regularly-cultured RPE1 cells expressing E7 or containing a vector, the levels of Cdks went down remarkably upon bleomycin treatment in vector but not E7-expressing cells (Fig. 2A, right panel). Therefore, there was a significant difference in steady-state levels of Cdks between RPE1 cells expressing E7 and containing vector upon DNA damage. Notably, the expression levels of Cdk1 and Cdk2 in RPE1 vector cells are higher compared with NIKS vector cells, probably due to the fact that RPE1 vector cells proliferate more efficiently than NIKS vector cells.

Figure 2.

Cdk1 is required for HPV E7 to abrogate DNA damage-induced G1 arrest. (A) Expression of Cdks in E7-expressing cells. The steady-state levels of Cdk1 and Cdk2 in E7-expressing or vector-containing NIKS and RPE1 cells treated with bleomycin or PBS were examined by immunoblotting. Actin-β was used as a loading control. (B) siRNAs targeting Cdk1 or Cdk2 specifically reduced their expressions. RPE1-E7 cells were transfected with Cdk1-siRNA and Cdk2-siRNA respectively. Cdk1 and Cdk2 protein levels were assessed by immunoblot analysis. Tubulin-β was used as a loading control. (C) RPE1-E7 cells were transfected with either Cdk1 or Cdk2 siRNAs and then treated with bleomycin. Cells were harvested at 72 hours post-transfection, stained with PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. A representative experiment of 6 is shown (Left panel). The percentage of cells at G1 phase is gated. Data of 6 experiments from RPE1-E7 cells are summarized (Right panel). (D) RPE1 E7 cells were transfected with either Cdk1 or Cdk2-siRNAs. Sixteen hours later, cells were treated with bleomycin for 32hrs. Cells were labeled with BrdU before being collected and stained with anti-BrdU antibody, counterstained with PI, analyzed by flow cytometry. Data from a representative of 4 experiments are shown (Left panel) and the percentage of BrdU-positive cells is gated. Data are summarized (Right panel). Error bars reflect the standard deviations of the mean. Si-NS, non-silencing siRNA.

Next we prepared siRNAs targeting Cdk1 and Cdk2 to examine their roles in E7-mediated abrogation of the DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint. As shown in Figure 2B, specific knockdown of Cdk1 and Cdk2 (For about 90%) was achieved in RPE1 cells expressing E7. Significantly, transfection of siRNA targeting Cdk1 but not cdk2 led to an increase in the number of E7-expressing RPE1 cells (On average from 18.5% to 30.0%) at G1 phase (Fig. 2C). We have recently shown that in response to bleomycin, cells expressing HPV-16 E7 bypass the G1 checkpoint but not the G2 checkpoint.36 Increase in the number of E7-expressing cells at G1 upon bleomycin treatment therefore indicates a cell cycle arrest at G1. Furthermore, knocking down of Cdk1 but not Cdk2 inhibited the ability of E7 to incorporate BrdU (On average from 20.4% to 11.4%), which was measured at an earlier time point (Fig. 2D). Although knocking down of Cdk2 increased the percentage of E7 expressing cells to incorporate BrdU to some extent, the increase is not statistically significant. Since transfection of Cdk1 siRNA by itself induced an increase in the number of cells at G2 (Not shown), there was a concern that this may in one way or another affect the formation of G1 peak shown in Figure 2C or BrdU incorporation presented in Figure 2D. However, since bleomycin-treated HPV-16 E7-expressing cells bypasses the G1 checkpoint but not the G2 checkpoint,36 increased number of cells at G2 phase by Cdk1 targeting siRNA may reduce but cannot increase the number of cells at G1 phase. Therefore, cells at G1 or G1/S transition shown in Figure 2 should be those at G1 phase instead of G2 phase before bleomycin treatment.

Role of B-Myb in Cdk1 upregulation and G1 checkpoint abrogation in E7-expressing cells

We were interested in how Cdk1 was upregulated in E7-expressing cells. One of the best-known biological activities for the high-risk HPV E7 is the ability to degrade pRb.45 pRb binds to activator E2Fs and inhibits their transcriptional activation of genes responsible for S-phase progression46 and genes regulating mitosis, such as B-Myb, which, together with E2Fs, is essential to turn on Cdk1 and other genes required for G2/M transition.22 Notably, ectopic expression of B-Myb can bypass p53-induced p21-mediated G1 arrest.23 Moreover, it was shown that B-Myb expression was increased in E7 cells. In addition, B-Myb is a putative cervical cancer biomarker.47 We therefore examined the steady-state level of B-Myb in E7-expressing cells. B-Myb was found to be elevated in NIKS cells expressing HPV-16 E7, either bleomycin treated (3.8-fold) or untreated (4.2-fold) (Fig. 3A). In RPE1 cells, although the B-Myb levels were not significantly different in asynchronous cells expressing E7 or containing a vector, upon bleomycin treatment, B-Myb level dropped to a very low level in the vector control cells but retained in E7-expressing cells (Fig. 3A). Thus the expression pattern of B-Myb was similar to that of Cdks in E7-expressing epithelial cells.

Figure 3.

B-Myb is important for E7 to up-regulate Cdk1 and abrogate G1 checkpoint. (A) Lysates from NIKS (Left panel) and RPE1 (Right panel) cells expressing E7 or containing vector treated with bleomycin or PBS were assessed for steady-state level of B-Myb by immunoblot. Actin-β was used as a loading control. (B) NIKS (Left panel) and RPE1 (Right panel) cells expressing E7 were transfected with siRNAs targeting B-Myb. The steady-state levels of B-Myb and Cdk1 were determined by Western blot. Actin-β was used as a loading control. A representative of 3 independent experiments is shown. (C) RPE1-E7 and the vector control cells were transfected with B-Myb siRNA, treated with bleomycin and analyzed by flow cytometry after PtdIns staining. A representative experiment of 4 is shown in the left panel. Data of 4 experiments are summarized (Right panel).

Next we examined the extent to which B-Myb knockdown affects the expression of Cdk1 in E7-expressing cells. As shown in Figure 3B, siRNA targeting B-Myb efficiently knocked down B-Myb expression in both NIKS and RPE1 cells expressing HPV E7 (75% and 70% reduction, respectively). Furthermore, in B-Myb knockdown NIKS and RPE1 cells expressing E7, the steady-state level of Cdk1 went down significantly (80% and 65% reduction, respectively) (Fig. 3B). Moreover, knockdown of B-Myb in RPE1 cells expressing E7 increased the number of cells at G1 phase by an average of 47% upon DNA damage (From average of 30.2% to 44.46%, Fig. 3C). These results indicate that B-Myb is required for Cdk1 up-regulation in E7-expressing cells and important for the cells to bypass the G1 cell cycle arrest upon DNA damage.

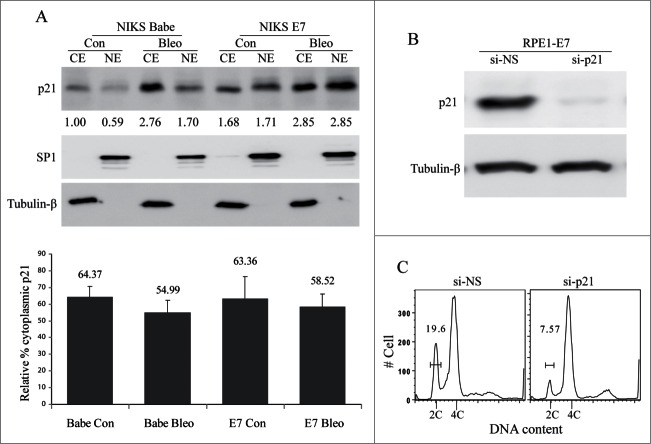

The localization and function of p21 in E7-expressing cells

There have been multiple explanations for how E7 maintains Cdk activity and promotes cell cycle progression in the presence of the Cdk inhibitor p21. One study suggested that E7 prevents p21 nuclear accumulation to retain cyclin E-Cdk2 activity.48 However, this experiment was only done in the mouse NIH 3T3 cells. To extend this observation, we examined p21 cellular localization in human epithelial cells. We performed Western blot analysis of p21 expression following sub-cellular fractionation to determine and quantify the intracellular localization of p21 in NIKS-E7 and the vector control cells after bleomycin treatment. The nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins were accordingly prepared and analyzed. Successful fractionation was demonstrated by expected sub-cellular localization of the nuclear (SP1) and cytoplasmic (Tubulin-β) protein markers (Fig. 4A, upper panel). Since equal amount of each protein fraction was used, the p21 level was an indication of its relative abundance in each cellular compartment after being normalized with SP1 and tubulin-β. Although p21 level was increased in E7-expressing NIKS cell as compared to the vector control cells and increased further upon bleomycin treatment, the majority of p21 proteins (63%) were indeed localized in the cytoplasm of E7-expressing NIKS cells (Fig. 4A, lower panel). However, the p21 distribution observed in the vector control cells was also mainly cytoplasmic (64% in cytoplasm) (Fig. 4A). Treatment with bleomycin did not significantly change the pattern of p21 localization in either E7 (59% in cytoplasm) or the vector control (55% in cytoplasm) cells. Similar observations were also made in RPE1 cells expressing E7 or containing vector (Data not shown). These results indicate that E7 does not significantly affect the cellular localization of p21 in immortalized human epithelial cells.

Figure 4.

Role of p21 in E7-mediated S-phase entry. (A) The cellular localization of p21 in E7-expressing cells. NIKS cells expressing HPV-16 E7 or vector (Babe) were treated with bleomycin or PBS, the cytoplasmic protein extract (CE) and nuclear protein extract (NE) were prepared, equal amount of total protein from each fraction were loaded to SDS-PAGE and blotted with antibodies specific for p21, SP1 (Nuclear protein marker) and tubulin-β (Cytoplasmic protein marker). Data from a representative experiment of 3 are shown. Relative amount of p21 based on the normalization with SP1 and Tubulin-β was labeled. Data are summarized in lower panel and described as relative percent of the cytoplasmic p21. (B) siRNAs targeting p21 specifically reduces its expressions. RPE1-E7 cells were transfected with p21-siRNAs and the steady-state level of p21 was monitored by immunoblot analysis. Tubulin-β was used as a loading control. A representative of 2 independent experiments is shown. (C) Role of p21 in E7-mediated abrogation of the G1 checkpoint. RPE1-E7 cells were transfected with siRNA targeting p21, treated with bleomycin, stained with PI and analyzed by flow cytometry. A representative experiment of 2 is shown.

HPV-16 E7 overrides the tumor suppressor activity of p21 in a transgenic model of cervical carcinogenesis.17 However, induction of S phase in differentiated human keratinocytes in the presence of p21 does not appear to be a frequent event and only occurs when high levels of E7 protein are induced.2 To reconcile the differences, we knocked down p21 in E7-expressing cells and examined its effect on abrogation of the G1 checkpoint by E7. As shown in Figure 4B, siRNA targeting p21 efficiently down-regulated the steady-state level of p21 (95% reduction). Moreover, knockdown of p21 in RPE1 expressing E7 cells decreased the percentage of cells at the G1 phase by more than 59% (On average reduced from 17.4% to 7.1%) upon DNA damage (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that although E7 can activate Cdk1 and abrogate DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint, p21 is still functioning to certain degree as a cell cycle inhibitor.

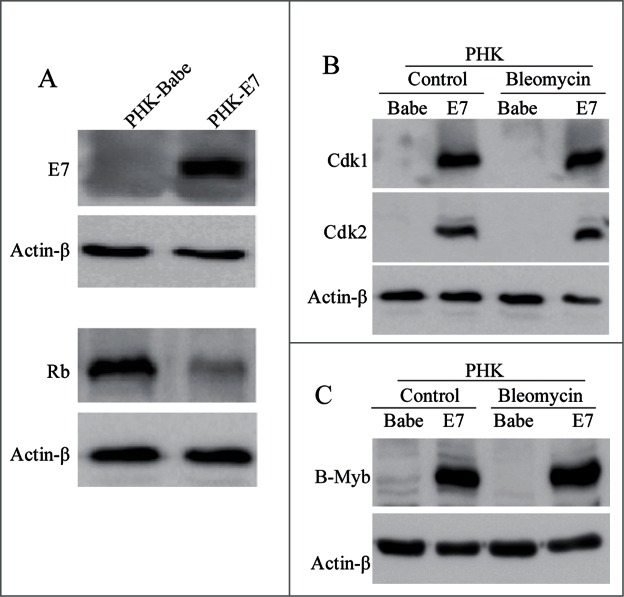

Upregulation of Cdks and B-Myb in PHKs expressing HPV-16 E7

To ascertain that the observations made in the immortalized epithelial cells are consistent with primary human keratinocytes, we examined the expression of the relevant proteins in PHKs expressing HPV-16 E7 by Western blot. As expected, E7 protein was readily detectable while pRb level was reduced in E7-expressing PHK cells (Fig. 5A). As shown in Figure 5B, both Cdk1 and Cdk2 were significantly increased in E7-expressing PHKs compared with the vector control PHKs. Upon DNA damage, there was no significant change in the steady-state levels of Cdk1 and Cdk2 in these cells, a pattern similar to what was observed in NIKS cells but not RPE1 cells. We also examined the steady-state level of B-Myb in E7-expressing cells. Consistent with what was observed in NIKS cells but not RPE1 cells, B-Myb was found to be elevated in PHKs expressing HPV-16 E7 compared with the vector control PHKs with and without bleomycin treatment (Fig. 5C). By comparison the patterns of B-Myb expression in the three cell lines under both normal culture condition and DNA damage, we conclude that B-Myb expression correlates with that of Cdks.

Figure 5.

Expression of cell cycle-related genes in E7-expressing PHKs. (A) Steady-state levels of HPV-16 E7 (Upper panel) and pRb (Lower panel) in PHKs were determined by immunoblotting. (B) The steady-state levels of Cdk1 and Cdk2 in PHKs expressing HPV-16 E7 treated with bleomycin or PBS were assessed by immunoblotting. (C) Expression of B-Myb in E7-expressing PHKs treated with bleomycin or PBS was measured by immunoblotting. Actin-β was used as a loading control. A representative of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the mechanism by which HPV-16 E7 abrogates DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint. Our studies demonstrated that both Cdk1 and Cdk2 were up-regulated in E7-expressing cells upon DNA damage. However, down-regulation of Cdk1 but not Cdk2 impaired the ability of E7 to abrogate the G1 checkpoint. We also provided evidence that B-Myb was required for Cdk1 up-regulation and abrogation of the G1 checkpoint in E7-expressing cells. As p21 binds Cdk1 with lower affinity than Cdk2, our results implicated a mechanism by which E7 bypasses the inhibitory effect of p21 to keep Cdks active. Nonetheless, our studies demonstrated that p21 still possessed partial function to arrest cells at G1 phase. These findings shed light on mechanisms by which HPV oncogene E7 modulates cell cycle checkpoint.

Originally, Cdk2 was believed to be essential for the G1/S transition while Cdk1 functions at the G2/M progression. This view has been challenged by accumulating evidence that Cdk2 is not necessary for the mitotic cell cycle in mammalian cells.6-10 On the other hand, a role for Cdk1 at the G1 checkpoint in the absence of Cdk2 has been demonstrated.6,7 In the absence of all 3 G1 Cdks, Cdk1 compensates for their functions.5,7,12 Nonetheless, in the presence of G1 Cdks, a role for Cdk1 in G1/S transition has not been demonstrated. The data presented in this study has implicated a role for Cdk1 at the G1 checkpoint in the presence of Cdk2 and other G1 Cdks in HPV E7-expressing cells. This function of Cdk1 may not be limited to cells expressing HPV E7. In this regard, these results call for a novel concept of Cdk1 function at cell cycle checkpoint.

Several previous studies have shown that B-Myb was upregulated in E7-expressing cells.29,30 However, increased steady-state level of B-Myb protein in E7-expressing keratinocytes has not been reported, neither did we know the functional role of B-Myb upregulation to HPV E7. This study provided evidence that B-Myb protein was increased in several E7-expressing epithelial cells including PHKs. Moreover, B-Myb was shown to be required for E7 to up-regulate Cdk1 and abrogate the G1 cell cycle checkpoint. The role of B-Myb has largely been considered in the G2/M transition for turning on Cdk1. Although B-Myb has been implicated in p53-induced p21-mediated G1 arrest,21,23 the mechanism is not known. Results from this study suggested that positive regulation of Cdk1 by B-Myb contributed to bypassing the DNA damage-induced G1 checkpoint. Since B-Myb expression is also increased in HPV-associated cancers, targeting B-Myb should have therapeutic significance.

There have been some debates regarding whether HPV E7 is capable of inactivating p21. E7 was reported to abrogate p21-mediated inhibition of Cdk2/cyclin A and cyclin E.15,44,49 In a mouse model, p21 inactivation by HPV-16 E7 partially contributed to cervical carcinogenesis.17 In epithelial raft culture systems of PHKs transduced with E7-expressing retroviruses, Dr. Chow and colleagues have observed more complicated interactions between cellular DNA synthesis and p21 as well as p27. Three populations of differentiated keratinocytes were observed2,50 (and reference therein). In one population, high levels of p21 and/or p27 but no cellular DNA replication was observed. In the other, p21/p27 was below detection while active DNA synthesis took place. In a very small number of cells, both p21 and BrdU signals were observed. However, since p21 protein might become stabilized after cellular DNA replication has taken place,51 simultaneous stain of p21 and BrdU in the same cells does not necessarily mean that p21 is functionally inactivated. Results from this study using siRNA targeting p21 in E7-expressing cells indicated that p21 was still functioning to certain degree as a cell cycle inhibitor (Fig. 4C). This observation reconciles the differences from previous studies regarding the functional interaction between HPV E7 and p21.

The mechanism by which E7 inactivates p21 is not fully understood. Initially it was proposed that E7 bound and inactivated p2139,59. Subsequently, it was shown that binding by E7 was not sufficient to inactivate p21.52 In contrast, an in vitro study suggested that p21 inhibited Cdk2 activity in spite of the presence of E7.53 Alternatively, inactivation of pRb and activation of E2F would trigger the synthesis of cyclin A and cyclin E, which may titrate p21.54,55 One study showed that E7 prevented p21 nuclear accumulation to retain cyclin E-Cdk2 activity in mouse NIH 3T3 cells.48 However, our studies suggested that E7 did not have a special effect on the cellular localization of p21 in human epithelial cells. The discrepancy could be explained by differences in cells used. p21 was originally identified as a universal inhibitor of cyclins that binds to various Cdk complexes.56,57 However, subsequent studies found that p21 binds Cdk1 with lower affinity than Cdk2.58 Our observation that Cdk1 instead of Cdk2 plays an important role in bypassing the G1 checkpoint in E7-expressing cells implicates a mechanism by which E7 abrogates the G1 checkpoint in the presence of p21.

Experimental Procedures

Cell culture

PHKs derived from neonatal human foreskin epithelium were obtained from the UMass Memorial Medical Center as described previously.34 Experiments were performed using PHKs within 3 passages. The spontaneously immortalized human keratinocyte NIKS cells were also described previously.34 PHKs and NIKS cells were cultured on mitomycin C-treated J2–3T3 feeder cells in E medium composed of 3 parts Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) and one part Ham's F-12 medium plus 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), with all supplements as previously described.34 The human telomerase reverse transcriptase–expressing human retinal pigment epithelium cell line (RPE1, described in)59 was maintained in a 1:1 dilution of DMEM–Ham's F-12 medium plus 10% FBS.

PHKs, NIKS and RPE1 cells expressing HPV-16 E7 were established using the pBabe retroviral system as described previously.36 Populations of infected cells were pooled and expanded. To ensure a high percentage of cells will express E7 or containing the retroviral vector, PHKs, NIKS and RPE1 derived cell lines were maintained in puromycin and used within 10 passages.

Immunoblotting

Protein extraction was prepared in lysis buffer (10 mmol/L Tris (pH 7.4), 1% SDS, 1.0 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate). Protein concentration was measured by the BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce) and confirmed by Coomassie Blue staining. Equal amount (30∼50 μg of whole cell extracts) of protein from each cell lysate were separated in SDS polyacrylamide gel (PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Filters were blotted with antibodies against Cdk1 (BD 610038), Cdk2 (sc-6248), pRb (BD 554136), tubulin-β (Sigma, T4026) and actin-β (Sigma, A-2066). For E7 and B-Myb protein detection, whole cell extracts were prepared in ML buffer (300 mM NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 20 mM Tris-HCl (PH8.0), 1 mM EDTA). E7 was detected with a mixture of anti-HPV-16 E7 antibodies 8C9 (Zymed/Invitrogen, #28–0006, at a 1:150 dilution) and ED17 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-6981, at a 1:200 dilution), using 100 μg of whole cell protein extracts separated on 12% SDS-PAGE. B-Myb was assessed by using 50 μg of whole cell protein extracts, separated on 8% SDS-PAGE and incubated with anti-B-Myb polyclonal antibody (sc-725). HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit was used as secondary antibodies. Relative quantification for each band was assessed by ImageJ software (NIH).

Cell fractionation

Preparation of the cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extracts was performed as described previously with slight modifications.60 In brief, cells treated with Bleomycin (10 μg/mL) for 16 hours were lysed using cell lysis buffer II containing 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.3% NP-40 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). After centrifugation, supernatants (Corresponding to the cytoplasmic extracts) were collected. The pellets were further washed with cold cell lysis buffer II and resuspended in nuclear extraction buffer (20 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 0.4 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and protease inhibitors). After a vigorous shaking for 30 min at 4°C, the nuclear extracts were collected by centrifugation. Equal amount of total proteins from each fraction were loaded to SDS-PAGE. Roughly, the total amount of proteins from the cytoplasmic fraction is 5 times that from the nuclear fraction. The nuclear and cytoplasmic p21 levels were measured with anti-p21 antibody (BD 610234). SP1 and tubulin-β were served as markers and loading controls for the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions respectively and detected with specific monoclonal antibodies (Anti-SP1, Cell signaling, # 9389; anti-tubulin-β, Sigma). Relative amount of p21 in each fraction was calculated based on the density of each band normalized with SP1 or tubulin-β.

RNAi

siRNA oligonucleotides were custom-made at Dharmacon, Inc.. The siRNA sense strand sequences were as follows: non-silencing control siRNA, 5-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGU-3′; Cdk1, 5′-GAU CAA CUC UUC AGG AUUU-3′ (Described previously in)61; Cdk2, 5′-GCC AGA AAC AAG UUG ACG G-3′ (Described previously in)61; B-Myb, 5′-GAU CUG GAU GAG CUG CAC U-3′ (Described previously in).62 p21, 5′-CAG UUU GUG UGU CUU AAU UAU-3′ (Described previously in).63 siRNAs were transfected into cells at a final concentration of 20 nM using the Lipofectamine 2000 or Oligofetamine according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). For gene knockdown experiment, cells were seeded onto a 60-mm dish the day before transfection. For transfection of NIKS cells, feeder cells were removed before transfection. Seventy-two hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and protein levels were analyzed by immunoblot.

Flow cytometry

For cell cycle analysis, approximately 1.2 × 105 cells were seeded onto 60 mm dish the day before siRNA transfection. Thirty-six hours post-transfection, cells were treated with 4–5 μg/ml bleomycin and incubated for an additional 36 hours, fixed in 70% ethanol overnight, resuspended in PBS, stained in propidium iodide (PI, 50 μg/mL in PBS; Sigma) staining solution supplemented with 70 μg/mL RNase A (Sigma), and analyzed by flow cytometry. Cell cycle profile was analyzed using the FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

For BrdU labeling experiment, asynchronous cultures of NIKS and RPE1 cells expressing HPV-16 E7 or vector were treated with bleomycin (10 μg/ml) or PBS for 16 hours (NIKS) or 36 hours (RPE1), respectively. BrdU was added to the medium 2 hours before collecting cells at a final concentration of 20 μM. Cells were then harvested and fixed in 70% ethanol overnight. The cells were permeabilized with 2 N HCl-0.5% Triton X-100, neutralized with 0.1 M sodium tetraborate, pH 8.5, stained with monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody (BD Biosciences), followed with anti-mouse IgG F(ab)2-FITC antibody (Sigma) and counterstained with PBS-PI-RNase A.

For BrdU labeling in siRNA transfected cells, RPE1-E7 cells were transfected with siRNA. Sixteen hours later, the cells were treated with bleomycin (5 μg/ml) for an additional 32 hours at 37°C. BrdU (Final 20 μM) was added to the medium 6–8 hours before collecting cells. Cells were then treated and analyzed as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Data quantifications were shown as the means ± SD (Standard deviation of the mean). Student's t-test was used to compare the differences between means. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the award R01CA119134 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

References

- 1. McCance DJ, Kopan R, Fuchs E, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus type 16 alters human epithelial cell differentiation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1988; 85:7169-73; PMID:2459699; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banerjee NS, Genovese NJ, Noya F, Chien WM, Broker TR, Chow LT. Conditionally activated E7 proteins of high-risk and low-risk human papillomaviruses induce S phase in postmitotic, differentiated human keratinocytes. J Virol 2006; 80:6517-24; PMID:16775338; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.02499-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kastan MB, Bartek J. Cell-cycle checkpoints and cancer. Nature 2004; 432:316-23; PMID:15549093; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature03097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murray AW. Recycling the cell cycle: cyclins revisited. Cell 2004; 116:221-34; PMID:14744433; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01080-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat. Rev 2009; 9:153-66; PMID:19238148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aleem E, Kiyokawa H, Kaldis P. Cdc2-cyclin E complexes regulate the G1/S phase transition. Nat Cell Biol 2005; 7:831-6; PMID:16007079; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santamaria D, Barriere C, Cerqueira A, Hunt S, Tardy C, Newton K, Caceres JF, Dubus P, Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cdk1 is sufficient to drive the mammalian cell cycle. Nature 2007; 448:811-5; PMID:17700700; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berthet C, Klarmann KD, Hilton MB, Suh HC, Keller JR, Kiyokawa H, Kaldis P. Combined loss of Cdk2 and Cdk4 results in embryonic lethality and Rb hypophosphorylation. Dev Cell 2006; 10:563-73; PMID:16678773; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ortega S, Prieto I, Odajima J, Martin A, Dubus P, Sotillo R, Barbero JL, Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 is essential for meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice. Nat Genet 2003; 35:25-31; PMID:12923533; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tetsu O, McCormick F. Proliferation of cancer cells despite CDK2 inhibition. Cancer Cell 2003; 3:233-45; PMID:12676582; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00053-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berthet C, Aleem E, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, Kaldis P. Cdk2 knockout mice are viable. Curr Biol 2003; 13:1775-85; PMID:14561402; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Satyanarayana A, Kaldis P. Mammalian cell-cycle regulation: several Cdks, numerous cyclins and diverse compensatory mechanisms. Oncogene 2009; 28:2925-39; PMID:19561645; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2009.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwarz E, Freese UK, Gissman L, Mayer W, Roggenbuck B, Stremlau A, zur Hausen H. Structure and transcription of human papillomavirus sequences in cervical carcinoma cells. Nature 1985; 314:111-4; PMID:2983228; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/314111a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen JJ. Genomic instability induced by human papillomavirus oncogenes. N Am J Med Sci 2010; 3:43-7; PMID:21643539; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.7156/v3i2p043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones DL, Alani RM, Munger K. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein can uncouple cellular differentiation and proliferation in human keratinocytes by abrogating p21Cip1-mediated inhibition of cdk2. Genes Dev 1997; 11:2101-11; PMID:9284049; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.11.16.2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moody CA, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation. Nat Rev 2010; 10:550-60; PMID:20592731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shin MK, Balsitis S, Brake T, Lambert PF. Human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein overrides the tumor suppressor activity of p21Cip1 in cervical carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 2009; 69:5656-63; PMID:19584294; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Demers GW, Espling E, Harry JB, Etscheid BG, Galloway DA. Abrogation of growth arrest signals by human papillomavirus type 16 E7 is mediated by sequences required for transformation. J Virol 1996; 70:6862-9; PMID:8794328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nomura N, Takahashi M, Matsui M, Ishii S, Date T, Sasamoto S, Ishizaki R. Isolation of human cDNA clones of myb-related genes, A-myb and B-myb. Nucleic Acids Res 1988; 16:11075-89; PMID:3060855; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/16.23.11075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sadasivam S, DeCaprio JA. The DREAM complex: master coordinator of cell cycle-dependent gene expression. Nat Rev 2013; 13:585-95; PMID:23842645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sala A, Calabretta B. Regulation of BALB/c 3T3 fibroblast proliferation by B-myb is accompanied by selective activation of cdc2 and cyclin D1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992; 89:10415-9; PMID:1438227; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhu W, Giangrande PH, Nevins JR. E2Fs link the control of G1/S and G2/M transcription. EMBO Journal 2004; 23(23):4615-26; PMID:15510213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin D, Fiscella M, O'Connor PM, Jackman J, Chen M, Luo LL, Sala A, Travali S, Appella E, Mercer WE. Constitutive expression of B-myb can bypass p53-induced Waf1/Cip1-mediated G1 arrest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91:10079-83; PMID:7937841; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen Y, Miller C, Mosher R, Zhao X, Deeds J, Morrissey M, Bryant B, Yang D, Meyer R, Cronin F, et al. Identification of cervical cancer markers by cDNA and tissue microarrays. Cancer Res 2003; 63:1927-35; PMID:12702585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Santin AD, Zhan F, Bignotti E, Siegel ER, Cane S, Bellone S, Palmieri M, Anfossi S, Thomas M, Burnett A, et al. Gene expression profiles of primary HPV16- and HPV18-infected early stage cervical cancers and normal cervical epithelium: identification of novel candidate molecular markers for cervical cancer diagnosis and therapy. Virology 2005; 331:269-91; PMID:15629771; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rampias T, Sasaki C, Weinberger P, Psyrri A. E6 and e7 gene silencing and transformed phenotype of human papillomavirus 16-positive oropharyngeal cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009; 101:412-23; PMID:19276448; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/jnci/djp017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Armstrong DJ, Roman A. The relative ability of human papillomavirus type 6 and human papillomavirus type 16 E7 proteins to transactivate E2F-responsive elements is promoter- and cell-dependent. Virology 1997; 239:238-46; PMID:9426463; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/viro.1997.8885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lam EW, Morris JD, Davies R, Crook T, Watson RJ, Vousden KH. HPV16 E7 oncoprotein deregulates B-myb expression: correlation with targeting of p107/E2F complexes. EMBO J 1994; 13:871-8; PMID:8112300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johung K, Goodwin EC, DiMaio D. Human papillomavirus E7 repression in cervical carcinoma cells initiates a transcriptional cascade driven by the retinoblastoma family, resulting in senescence. J Virol 2007; 81:2102-16; PMID:17182682; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.02348-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pang CL, Toh SY, He P, Teissier S, Ben Khalifa Y, Xue Y, Thierry F. A functional interaction of E7 with B-Myb-MuvB complex promotes acute cooperative transcriptional activation of both S- and M-phase genes. (129 c). Oncogene 2013; 33(31):4039-49; PMID:24141769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Demers GW, Foster SA, Halbert CL, Galloway DA. Growth arrest by induction of p53 in DNA damaged keratinocytes is bypassed by human papillomavirus 16 E7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91:4382-6; PMID:8183918; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Slebos RJC, Lee MH, Plunkett BS, Kessis TD, Williams BO, Jacks T, Hedrick L, Kastan MB, Cho KR. p53-dependent G1 arrest involves pRB-related proteins and is disrupted by the human papillomavirus 16 E7 oncoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1994; 91:5320-4; PMID:8202487; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hickman ES, Picksley SM, Vousden KH. Cells expressing HPV16 E7 continue cell cycle progression following DNA damage induced p53 activation. Oncogene 1994; 9:2177-81; PMID:8036003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu Y, Heilman SA, Illanes D, Sluder G, Chen JJ. p53-independent abrogation of a postmitotic checkpoint contributes to HPV E6-induced polyploidy. Cancer Res 2007; 67:2603-10; PMID:17363579; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang W, Li J, Kanginakudru S, Zhao W, Yu X, Chen JJ. The human papillomavirus type 58 E7 oncoprotein modulates cell cycle regulatory proteins and abrogates cell cycle checkpoints. Virology 2010; 397:139-44; PMID:19945133; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fan X, Liu Y, Heilman SA, Chen JJ. Human papillomavirus E7 induces rereplication in response to DNA damage. J Virol 2013; 87:1200-10; PMID:23152514; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.02038-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chen J, Stubbe J. Bleomycins: towards better therapeutics. Nat Rev 2005; 5:102-12; PMID:15685195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duensing S, Munger K. The human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncoproteins independently induce numerical and structural chromosome instability. Cancer Res 2002; 62:7075-82; PMID:12460929 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rogoff HA, Pickering MT, Frame FM, Debatis ME, Sanchez Y, Jones S, Kowalik TF. Apoptosis associated with deregulated E2F activity is dependent on E2F1 and Atm/Nbs1/Chk2. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24:2968-77; PMID:15024084; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2968-2977.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Banerjee NS, Wang HK, Broker TR, Chow LT. Human papillomavirus (HPV) E7 induces prolonged G2 following S phase reentry in differentiated human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:15473-82; PMID:21321122; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.197574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature 1993; 362:709-15; PMID:8469282; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/362709a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Malumbres M, Barbacid M. Mammalian cyclin-dependent kinases. Trends Biochem Sci 2005; 30:630-41; PMID:16236519; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McLaughlin-Drubin ME, Munger K. The human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Virology 2009; 384:335-44; PMID:19007963; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Funk JO, Waga S, Harry JB, Espling E, Stillman B, Galloway DA. Inhibition of CDK activity and PCNA-dependent DNA replication by p21 is blocked by interaction with the HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein. Genes Dev 1997; 11:2090-100; PMID:9284048; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.11.16.2090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Boyer SN, Wazer DE, Band V. E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cancer Res 1996; 56:4620-4; PMID:8840974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cobrinik D. Pocket proteins and cell cycle control. Oncogene 2005; 24:2796-809; PMID:15838516; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1208619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Astbury K, McEvoy L, Brian H, Spillane C, Sheils O, Martin C, O'Leary JJ. MYBL2 (B-MYB) in cervical cancer: putative biomarker. Int J Gynecol Cancer: Official J Int Gynecol Cancer Soc 2011; 21:206-12; PMID:21270603; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/IGC.0b013e318205759f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Westbrook TF, Nguyen DX, Thrash BR, McCance DJ. E7 abolishes raf-induced arrest via mislocalization of p21(Cip1). Mol Cell Biol 2002; 22:7041-52; PMID:12242284; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.22.20.7041-7052.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zerfass-Thome K, Zwerschke W, Mannhardt B, Tindle R, Botz JW, Jansen-Durr P. Inactivation of the cdk inhibitor p27KIP1 by the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein. Oncogene 1996; 13:2323-30; PMID:8957073 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Noya F, Chien WM, Broker TR, Chow LT. p21cip1 Degradation in differentiated keratinocytes is abrogated by costabilization with cyclin E induced by human papillomavirus E7. J Virol 2001; 75:6121-34; PMID:11390614; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6121-6134.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chien WM, Noya F, Benedict-Hamilton HM, Broker TR, Chow LT. Alternative fates of keratinocytes transduced by human papillomavirus type 18 E7 during squamous differentiation. J Virol 2002; 76:2964-72; PMID:11861862; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.76.6.2964-2972.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Helt AM, Funk JO, Galloway DA. Inactivation of both the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor and p21 by the human papillomavirus type 16 E7 oncoprotein is necessary to inhibit cell cycle arrest in human epithelial cells. J Virol 2002; 76:10559-68; PMID:12239337; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10559-10568.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. He W, Staples D, Smith C, Fisher C. Direct activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 by human papillomavirus E7. J Virol 2003; 77:10566-74; PMID:12970441; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10566-10574.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ruesch MN, Laimins LA. Initiation of DNA synthesis by human papillomavirus E7 oncoproteins is resistant to p21-mediated inhibition of cyclin E-cdk2 activity. J Virol 1997; 71:5570-8; PMID:9188631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ruesch MN, Laimins LA. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins alter differentiation-dependent cell cycle exit on suspension in semisolid medium. Virology 1998; 250:19-29; PMID:9770416; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/viro.1998.9359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xiong Y, Hannon G, Zhang H, Casso D, Kobayashi R, Beach D. p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature 1993; 366:701-4; PMID:8259214; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/366701a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. El-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer WE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 1993; 75:817-25; PMID:8242752; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Harper JW, Elledge SJ, Keyomarsi K, Dynlacht B, Tsai LH, Zhang P, Dobrowolski S, Bai C, Connell-Crowley L, Swindell E, et al. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by p21. Mol Biol Cell 1995; 6:387-400; PMID:7626805; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.6.4.387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Uetake Y, Sluder G. Cell cycle progression after cleavage failure: mammalian somatic cells do not possess a "tetraploidy checkpoint." J Cell Biol 2004; 165:609-15; PMID:15184397; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200403014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zou Y, Mi J, Cui J, Lu D, Zhang X, Guo C, Gao G, Liu Q, Chen B, Shao C, et al. Characterization of nuclear localization signal in the N terminus of CUL4B and its essential role in cyclin E degradation and cell cycle progression. J Biol Chem 2009; 284:33320-32; PMID:19801544; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M109.050427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. L'Italien L, Tanudji M, Russell L, Schebye XM. Unmasking the redundancy between Cdk1 and Cdk2 at G2 phase in human cancer cell lines. Cell Cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 2006; 5:984-93; PMID:16687918; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.5.9.2721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Garcia P, Frampton J. The transcription factor B-Myb is essential for S-phase progression and genomic stability in diploid and polyploid megakaryocytes. J Cell Sci 2006; 119:1483-93; PMID:16551698; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.02870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jiang WQ, Zhong ZH, Nguyen A, Henson JD, Toouli CD, Braithwaite AW, Reddel RR. Induction of alternative lengthening of telomeres-associated PML bodies by p53/p21 requires HP1 proteins. J Cell Biol 2009; 185:797-810; PMID:19468068; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200810084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]