Abstract

Venous malformations (VMs) are localized defects in vascular morphogenesis frequently caused by mutations in the gene for the endothelial tyrosine kinase receptor TIE2. Here, we report the analysis of a comprehensive collection of 22 TIE2 mutations identified in patients with VM, either as single amino acid substitutions or as double-mutations on the same allele. Using endothelial cell (EC) cultures, mouse models and ultrastructural analysis of tissue biopsies from patients, we demonstrate common as well as mutation-specific cellular and molecular features, on the basis of which mutations cluster into categories that correlate with data from genetic studies. Comparisons of double-mutants with their constituent single-mutant forms identified the pathogenic contributions of individual changes, and their compound effects. We find that defective receptor trafficking and subcellular localization of different TIE2 mutant forms occur via a variety of mechanisms, resulting in attenuated response to ligand. We also demonstrate, for the first time, that TIE2 mutations cause chronic activation of the MAPK pathway resulting in loss of normal EC monolayer due to extracellular matrix (ECM) fibronectin deficiency and leading to upregulation of plasminogen/plasmin proteolytic pathway. Corresponding EC and ECM irregularities are observed in affected tissues from mouse models and patients. Importantly, an imbalance between plasminogen activators versus inhibitors would also account for high d-dimer levels, a major feature of unknown cause that distinguishes VMs from other vascular anomalies.

Introduction

Venous malformations (VMs) are slow-flow, non-proliferative vascular anomalies, most often located on skin and mucosa. Lesions are present at birth and grow proportionately with the individual. They can become extensive causing chronic complications such as pain, bleeding, disfigurement, functional impairment and local thrombosis (1). Available therapies are sclerotherapy and surgical resection; however, both are invasive and often ineffective as lesions tend to recur (2). Here, we tackle two major obstacles to the development of targeted, molecular therapies: limited understanding of disease mechanisms, and lack of appropriate model systems for VM research.

About 50% of VMs are associated with mutations in the gene for the endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase TIE2 (TEK) (3,4). Mutations are located in exons 15, 17, 22 and 23, encoding the intracellular tyrosine kinase, kinase insert and carboxyl-terminal tail domains. They result in amino acid changes or C-terminal premature stop codons and can occur either singly or as double-mutations on the same allele (3,4). All identified TIE2 mutations increase TIE2 autophosphorylation when expressed in cultured cells (3–7). The autophosphorylation state is highly variable, however, and no correlation between disease severity, number or location of lesions and TIE2 activation state has been observed. This suggests that TIE2 substitutions cause qualitative rather than simply quantitative changes in cellular signaling. We investigated these changes by systematically and comprehensively comparing 22 VM-associated TIE2 mutations (Fig. 1) using biochemical and cell biological methods, in vivo VM mouse model and patient biopsies. Our analysis is unique in including a series of (causative) double-hit substitutions and their single constituent mutations, in order to identify additive/synergistic effects on lesion formation. We observed cellular and molecular features that are common to most mutant forms and others that are specific to certain subsets. This allowed for hierarchical clustering of mutations, which fall into categories including constituent single mutations versus disease-causative double-mutations, as suggested by genetic studies.

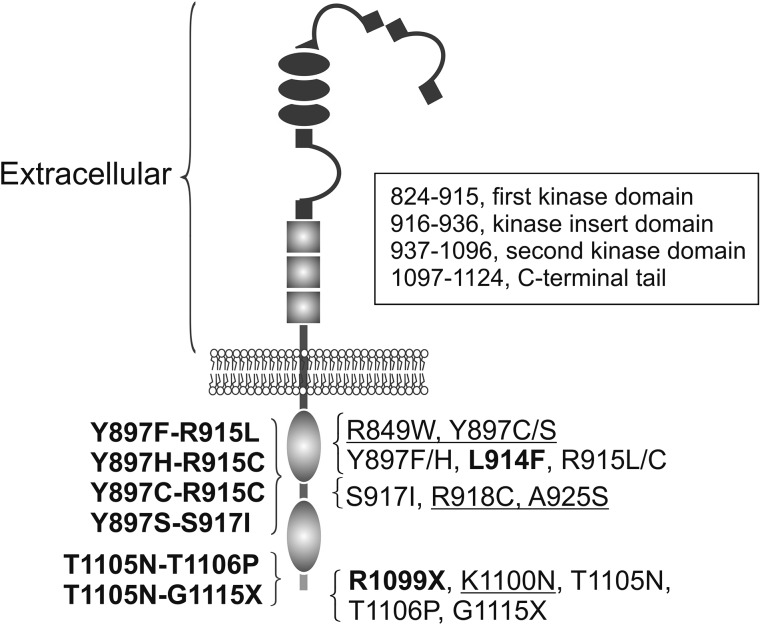

Figure 1.

TIE2 primary structure, heredity and locations of mutations studied. Germline mutations are underlined and somatic mutations found in lesions in bold. Double-mutations (disease-causative) are listed on the left. Single mutations (normal font) constituting the double hit mutations are thought to be predisposing. In addition, the common germline R849W is proposed to need a somatic second-hit to cause VMs (4). TIE2 domain amino acid numbers (framed) based on Shewchuk et al. (8) and Uniprot-database.

We show, for the first time, that TIE2 mutations cause a pronounced change in EC monolayer morphology due to activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and loss of extracellular matrix (ECM) fibronectin (FN). It also strongly induces the plasminogen/plasmin proteolytic system which may explain why VMs, uniquely among vascular anomalies, are characterized by coagulopathy in the form of high d-dimer levels (9–12). Using ultrastructural analysis of patient biopsies and experimental lesions grown in mice, we demonstrate distinctive morphological features of TIE2 mutation-positive VM ECs and perivascular ECM organization in lesions, corresponding to the abnormalities observed in vitro. In addition to revealing cellular and molecular features that separate VMs from normal vessels, useful in developing diagnostic criteria and read-outs for normalization by therapy, our study describes a mouse model that recapitulates pathognomonic features of human disease, establishing its usefulness as a disease model.

Results

TIE2 mutations show both common and mutation-specific effects on TIE2 activation, cellular distribution and downstream signaling

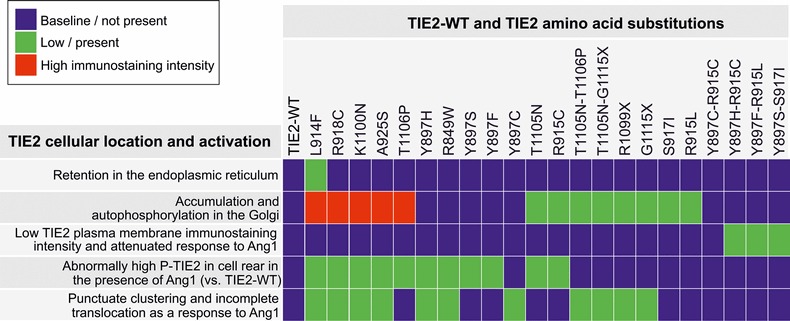

We investigated the effects of 22 inherited and sporadic TIE2 mutations (Fig. 1) in retrovirally transduced human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Angiopoietin-1 (Ang1) ligand-binding by wild-type (WT) TIE2 induces its subcellular translocation and activation, with cell compartment-specific effects on downstream signaling (13–15). We therefore compared the effects of mutations on TIE2 trafficking. Table 1 shows a comparison of subcellular location and activation of TIE2 mutations, and Supplementary Material, Figure S1 shows representative confocal microscopy images.

Table 1.

Comparison of subcellular location and activation of TIE2 mutations

|

HUVECs retrovirally transduced with TIE2 forms indicated were stimulated for 1 h with Ang1 or left unstimulated, fixed and stained for immunofluorescent confocal microscopy to detect the subcellular localization and activation of the TIE2. Representative images are shown in Supplementary Material, Figure S1.

In the absence of added ligand, partial TIE2 retention in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) was observed in the case of the most common somatic mutation L914F. Three out of four Y897 double-mutations, but no other TIE2 form, showed low TIE2 immunostaining intensity at the plasma membrane. Accumulation and ligand-independent phosphorylation in an inappropriate compartment, namely the Golgi, was observed with 13 of 22 mutations (including L914F), thus representing a common alteration from the WT state.

In sparsely plated ECs, Ang1-ligand stimulates TIE2 translocation and activation in the cell rear and in retraction fibers, which may represent former cell-matrix adhesion sites (14,15). With 11 of 22 mutations, we observed abnormally high phospho-TIE2 staining in these compartments in the presence of Ang1, indicating that enhancement of ligand-induced TIE2 activation in the cell–ECM interface is a fairly common feature. In contacting cells Ang1 induces rapid clustering, translocation and phosphorylation of TIE2 in cell–cell junctions (13,14). In 11 mutated TIE2-transduced HUVECs, Ang1-induced receptor clustering and translocation was incomplete, indicating a common defect in ligand-regulated translocation. These included 8 (of the 13) mutant forms that showed Golgi retention in the absence of ligand, indicating that access to ligand may contribute to this effect.

The degree of TIE2 ligand-independent tyrosine phosphorylation (P-Tyr) in HUVEC lysates varied strongly between mutant forms (Supplementary Material, Table S1 and Supplementary Material, Fig. S2): ten mutations showed mild (<5), four mutations moderate (5–10) and six mutations high TIE2 P-Tyr (>10 times over TIE2-WT). Seven mutations showed attenuated response to Ang1; in these cells, Ang1 either failed to increase P-Tyr when compared with the corresponding unstimulated mutant cells, or the fold increase in phosphorylation was low (less than 1.5-fold). In terms of increase in TIE2 P-Tyr, only five mutants responded to Ang1 stimulatory effect as did TIE2-WT.

Ang1-mediated activation of TIE2 induces activation of Akt and Erk1/2 (13,16,17), and we next investigated mutation-induced, ligand-independent Akt and Erk phosphorylation. Increases in P-Akt (Ser473) and P-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) were observed to varying degrees (Supplementary Material, Table S1 and Fig. S2). In general, increases in Akt and Erk phosphorylation reflected TIE2 autoactivation states; however, some deviating responses were also observed: TIE2 P-Tyr was low in A925S and T1105N, but increased Erk (A925S) and both Akt and Erk activation (T1105N) were nevertheless observed. Surprisingly, R1099X, which lacks the C-terminal Tyr-residues implicated in Ang1-induced TIE2/Akt signaling (18,19), induced relatively high TIE2 P-Tyr and P-Akt, but lower P-Erk.

When double-mutations and their constitutive single mutations were compared, both similarities and differences were evident. In the case of Y897S-S917I, Y897H-R915C and Y897C-R915C, the effects of the single mutations on TIE2 phosphorylation were compounded by their combination. In Y897F-R915L, T1105N-T1106P and T1105N-G1115X, in contrast, no significant increase in autoactivation state was observed when compared with the more strongly phosphorylated constituent single mutation (R915L, T1106P and G1115X), suggesting that an increase in TIE2 phosphorylation is not sufficient to transform a single mutation into a disease-causative double-mutation. Instead, disease-causative forms (i.e. mutations found in VM-lesions) caused defective TIE2 receptor clustering and translocation in response to Ang1 more often (8 out of 12, 67%) than mutations not found in lesions alone (3 out of 10, 30%), i.e. R849W and double-hit constituting single mutations.

Taken together, the different mutations show diverse effects in terms of ligand-independent TIE2 phosphorylation in cell lysates, increase in phosphorylation in response to activating Ang1 ligand, TIE2 trafficking, subcellular localization and downstream signaling. Overall, TIE2 trafficking (the subcellular site of activation and/or ligand-induced receptor clustering and translocation) was abnormal in most cases (21 out of 22 mutations, 95%), likely hampering normal ligand-regulated TIE2 signaling in specific cell compartments (13,14).

Defective glycosylation and abnormal intracellular clustering, but not increased phosphorylation, may contribute to intracellular retention of TIE2-L914F

To identify molecular mechanisms for the intracellular retention of mutated TIE2, we investigated the roles of phosphorylation, glycosylation and intracellular dimerization/clustering, previously implicated in altered receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) trafficking through the secretory pathway (20–25).

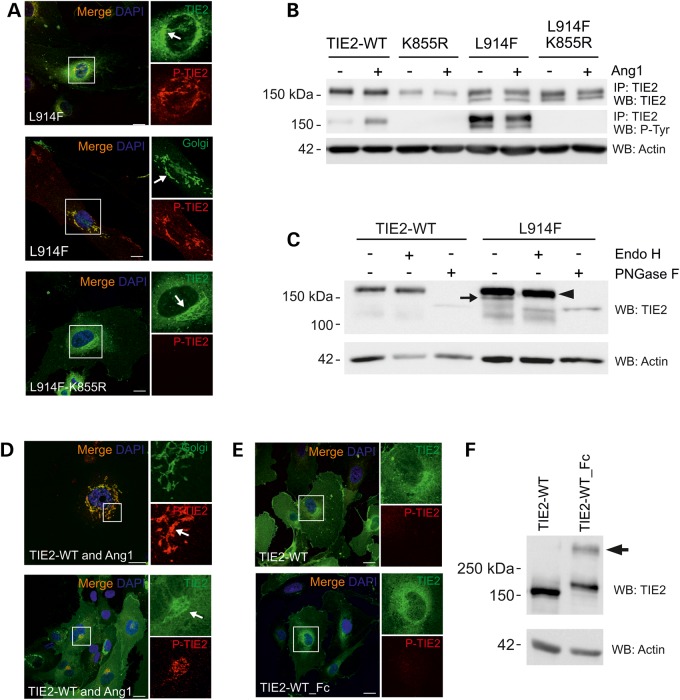

We first studied the contribution of increased phosphorylation by combining the most common TIE2 VM mutation, L914F, with a kinase-inactivating mutation K855R (26) allowing for the analysis of L914F in the absence of mutation-induced TIE2 P-Tyr. This indicated that L914F retention is not phosphorylation-dependent, as Golgi accumulation was observed with the L914F-K855R construct (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Incomplete N-linked glycosylation and premature intracellular clustering, but not increased phosphorylation may contribute to Golgi retention of TIE2-L914F. (A) HUVECs were transduced with TIE2-L914F combined with the kinase-inactivating mutation K855R and stained for confocal microscopy. Arrow indicates intensive perinuclear staining in the Golgi. (B) TIE2 was immunoprecipitated and P-Tyr state was analyzed in cell lysates. K855R abrogated mutant TIE2 P-Tyr. Also notice two prominent protein forms in L914F. (C) Cell lysates from transduced HUVECs were undigested, or digested with Endo H or PNGase F and protein migration was analyzed in western blot. Undigested (−) TIE2-L914F migrated as two protein bands, Endo H sensitive form is indicated by an arrow. PNGase F digested both immature (Endo H sensitive) and fully glycosylated forms (arrowhead). (D) HUVECs were co-transduced with TIE2-WT and Ang1 or (E) with TIE2-WT_Fc fusion to induce intracellular receptor clustering and dimerization, respectively, and stained for confocal microscopy. Scale bar 25 µm. (D) Ang1 clustered TIE2 is activated and accumulated in the Golgi. (E) TIE2-WT and TIE2-WT_Fc show some perinuclear TIE2 staining, but no apparent accumulation or P-TIE2 in the Golgi. (F) Non-reduced western blot analysis of TIE2-WT_Fc shows dimeric TIE2 (arrow). IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, western blot.

N-linked glycosylation, which regulates protein trafficking, is a common post-translational modification in the maturation of many RTKs. Glycosylation analysis of L914F revealed a predominant endoglycosidase H (Endo-H) sensitive (immature precursor) form (27) when compared with TIE2-WT, indicating that L914F is less efficiently processed into mature, Endo H-resistant glycoprotein (Fig. 2C).

Premature dimerization of insulin receptors leads to less efficient maturation and intracellular retention of dimeric or aggregated receptors (24). In addition, bimolecular fluorescence complementation assays in transfected HEK293T cells indicate that TIE2-R849W may ligand-independently form dimers more efficiently than TIE2-WT (28). To investigate if prematurely clustered TIE2 shows intracellular retention, we co-expressed TIE2-WT and Ang-1 ligand in HUVECs. This caused TIE2 retention and activation in the Golgi, similar to L914F. Golgi retention was not observed, however, with a designed dimeric TIE2-WT_Fc fusion protein (Fig. 2E and F).

Collectively, these results suggested that inefficient glycosylation but not increased P-Tyr may contribute to the intracellular retention of TIE2-L914F. It is possible that premature clustering contributes to defective trafficking; however, dimeric TIE2-WT_Fc fusion protein was able to exit the Golgi.

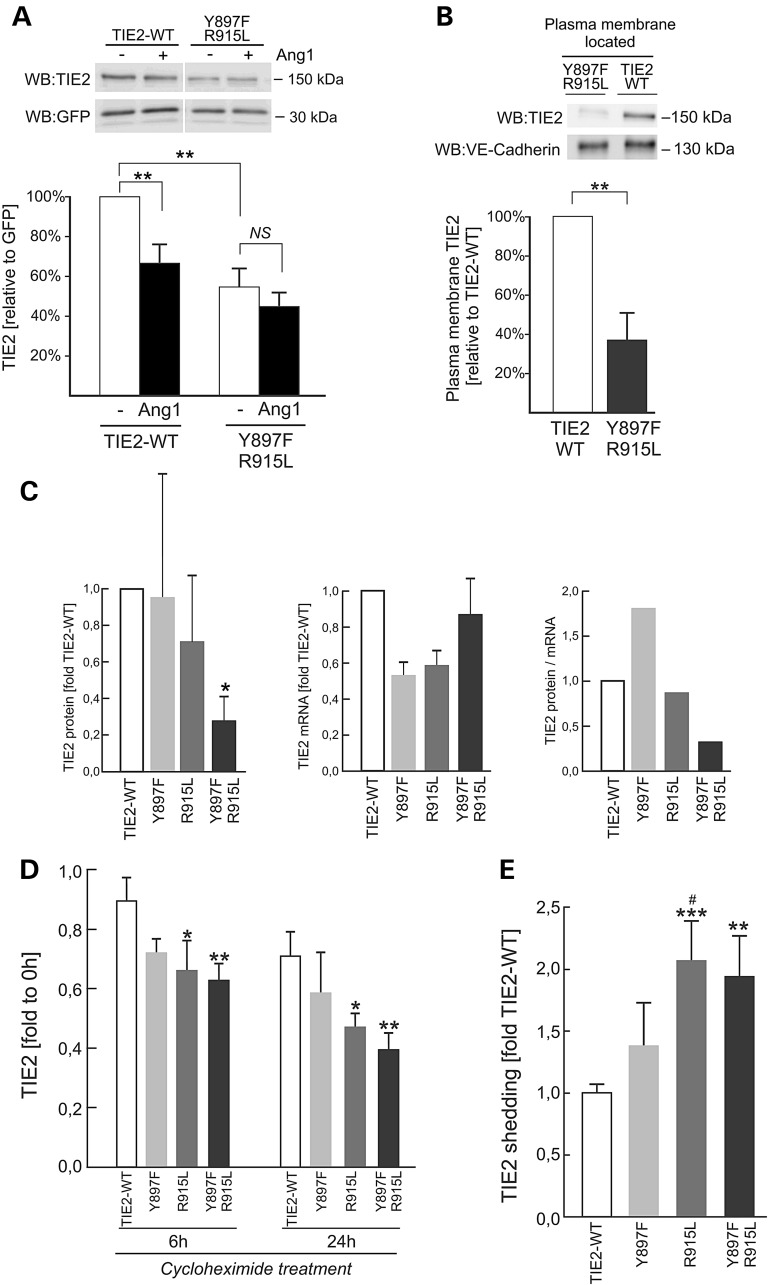

Increased protein turnover rate reduces levels of plasma membrane-localized Y897 double-mutants

A qualitatively distinct effect observed in Y897F-R915L, Y897H-R915C and Y897S-S917I expressing HUVECs was that double-mutations showed relatively low plasma membrane immunostaining when compared with the single constituent mutations (Table 1 and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). To investigate why, we transduced HUVECs with bicistronic TIE2-WT- or Y897F-R915L-IRES-GFP constructs, allowing for normalization of TIE2 transfection efficiency with simultaneously expressed GFP. In the absence of Ang1-ligand, the amount of TIE2 (normalized to GFP) in Y897F-R915L transduced HUVECs was about half that in TIE2-WT-transduced cells (Fig. 3A). Stimulation of TIE2-WT-HUVECs with Ang1 reduced TIE2 amount by 36%, probably due to internalization as previously described (29). Interestingly, this decrease was not observed in Y897F-R915L cells (Fig. 3A). To investigate the amount of TIE2 on the plasma membrane where binding to Ang1-ligand occurs, plasma membrane protein fractions were extracted in a biotinylation experiment (Fig. 3B). Plasma membrane-localized Y897F-R915L was found to be 63% less than TIE2-WT. To compare Y897F-R915L protein and mRNA levels to TIE2-WT and the single substitutions Y897F and R915L, HUVECs were transfected with the respective bicistronic TIE2-IRES-GFP forms, selected for GFP using FACS, and assessed for TIE2 expression by western blotting and qPCR (Fig. 3C). The TIE2 protein/mRNA ratio was strongly diminished in the case of Y897F-R915L, but not the single-mutants. Inhibition of protein synthesis using cycloheximide (Fig. 3D) caused a significantly greater decrease in Y897F-R915L than in TIE2-WT, indicating accelerated turnover of double-mutated TIE2. Comparisons of Y897F-R915L with the single constituent Y897F and R915L forms showed a trend for an additive effect.

Figure 3.

Supplemental mutations accelerate TIE2 degradation at the plasma membrane. (A) HUVECs were transduced with bicistronic TIE2-IRES-GFP, left unstimulated or stimulated with Ang1 for 30 min and lysed. TIE2 and GFP were analyzed in western blot and signal intensities were quantified. In non-stimulated Y897F-R915L expressing cells, the total amount of TIE2 protein is reduced. Ang1-stimulation reduced TIE2 amount in TIE2-WT, but not in Y897F-R915L. **P < 0.01, n = 12, means + SD; NS, non-significant in two tailed t-test. (B) Plasma membrane located protein fractions were extracted in a biotinylation experiment, amounts of TIE2 and VE-Cadherin (as a control) were compared in western blot, and signal intensities were quantified. The plasma membrane located Y897F-R915L is less than in TIE2-WT (**P < 0.01 in two tailed t-test, n = 10). (C) HUVECs were transfected with bicistronic TIE2-IRES-GFP, TIE2 protein (left) and mRNA (middle) were quantified in western blot and quantitative PCR and protein/mRNA ratio was calculated (right). Y897F-R915L protein (*P < 0.05 versus TIE2-WT in ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test) but not mRNA is reduced. Single mutations show a trend for additive effect for diminished protein/mRNA ratio. (D) Protein synthesis was inhibited using cycloheximide and total protein was collected in the indicated time-points, and measured in TIE2 ELISA. In R915L and Y897F-R915L, the TIE2 protein amount decreased faster than in TIE2-WT. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 in ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test; means + SD, n = 2–4 independent experiments run in duplicates. (E) Amount of soluble TIE2 in the conditioned medium was measured in TIE2 ELISA from HUVECs expressing TIE2 forms indicated and normalized to TIE2 amount in corresponding cell lysates and total protein concentration. Amount of shed TIE2 increases in Y897F-R915L and in R915L when compared with TIE2-WT (TIE2-WT set to 1.0, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 versus TIE2-WT and #P < 0.05 versus Y897F in ANOVA followed by the Tukey's post hoc test, n = 4).

Previous studies have suggested that TIE2 signaling can be downregulated by shedding of the extracellular domain of the receptor in an Akt phosphorylation-dependent mechanism (30,31). We found that the amount of soluble TIE2 was elevated in conditioned medium from Y897F-R915L and R915L transduced HUVECs compared with TIE2-WT (Fig. 3E), suggesting that TIE2 shedding may be one mechanism causing decreased TIE2 protein at the cell surface, hampering extracellular ligand-controlled functions.

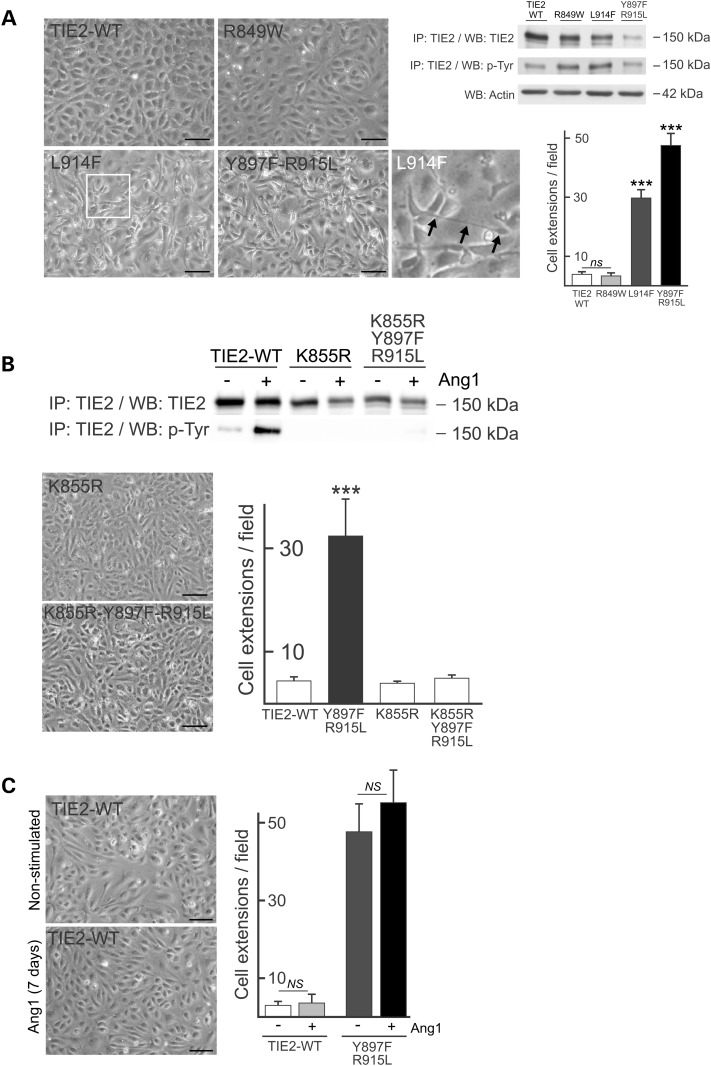

TIE2 mutations cause a kinase activity-dependent loss of endothelial cobblestone morphology

Microscopic analysis of mutated TIE2 expressing HUVECs revealed a highly elongated and overlapping cell morphology, clearly distinct from the typical cuboidal cobblestone morphology characteristics of normal, confluent ECs (Fig. 4A). The alteration in morphology was observed to varying degrees in all mutants analyzed (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3), with a positive correlation between the strength of TIE2 autoactivation and the severity of the morphological change (Fig. 4A). To investigate the role of increased TIE2 phosphorylation in altering the EC monolayer, we combined Y897F-R915L with the kinase-inactivating mutation K855R in cis. In HUVECs transduced with this construct, cell monolayer morphology was restored to the typical endothelial cobblestone appearance (Fig. 4B), indicating that perturbation of the EC monolayer is dependent on TIE2 kinase activity. Prolonged stimulation of TIE2-WT HUVECs with Ang1 did not however induce loss of the cobblestone pattern (Fig. 4C), indicating that the perturbed monolayer is not due to chronic activation of normal TIE2 signaling, but represents a mutation-specific effect. Live cell imaging of TIE2-WT HUVECs revealed a parallel mode of cell migration, with reduced cell motility in confluent cell islets that formed a typical cobblestone layer. In striking contrast, in mutated TIE2 HUVECs, random cell migration was evident, with elongated, overlapping cells that fail to form a cobblestone pattern (Supplementary Material, Movie S1).

Figure 4.

Expression of mutant TIE2 leads to loss of endothelial cobblestone monolayer morphology depending on increase in kinase activity. (A) HUVECs transfected with TIE2-WT or mutant forms indicated were cultured to late confluence and imaged using phase contrast microscopy (left). WT cobblestone morphology is lost in variable decrees in mutant TIE2 expressing ECs showing elongated cellular structures locating on top of adjacent ECs (arrows in L914F inset). Immunoprecipitation (IP) and western blot (WB) analysis of total cell lysates of TIE2 forms indicated and the frequency of cellular extensions quantified from microscopy images. (B) IP and WB analysis of total cell lysates from transduced HUVECs. K855R abrogated mutant TIE2 kinase activity and in combination with double-mutation Y897F-R915L restored the cobblestone monolayer morphology. (C) Prolonged stimulation with TIE2 activating Ang1-ligand did not alter TIE2-WT or mutant monolayer morphology. NS, non-significant and ***P < 0.001 versus other cell lines in ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test, means + SD; n = 3. Scale bar 100 μm.

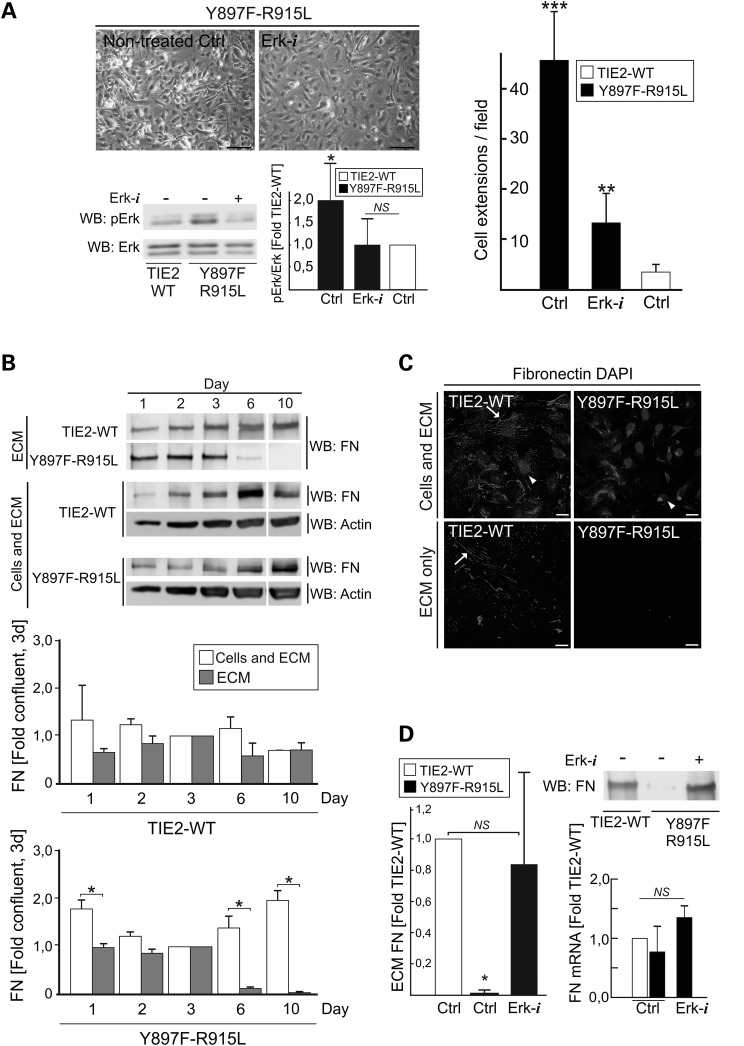

Loss of endothelial cobblestone pattern results from activation of the MAPK signaling pathway and loss of ECM FN

Loss of EC cobblestone morphology was found to be common alteration to all disease-causative TIE2 mutations. To investigate if mutant TIE2-induced Akt or Erk1/2 signaling contribute to this defect, we tested pharmacological inhibitors of PI3K/Akt (LY294002) and Mek1/Erk1/2 (PD98059). Erk1/2 inhibition was sufficient to restore the monolayer morphology of Y897F-R915L HUVECs (Fig. 5A) while Akt inhibition had no clear effect, alone or in combination with Erk1/2 inhibition.

Figure 5.

Loss of EC cobblestone morphology results from MAPK signaling pathway dependent loss of ECM FN. (A) TIE2-WT and Y897F-R915L HUVECs were cultured without (Ctrl) or with Erk inhibitor (Erk-i) for 7 days. Erk-i diminishes Erk phosphorylation to TIE2-WT level (left) and restores the cobblestone morphology close to WT (right). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus TIE2-WT or Erk-i treated Y897F-R915L; *P < 0.05 versus Erk-i treated Y897F-R915L or TIE2-WT Ctrl, n = 7. (B) Cells were lysed and total FN protein (containing both cellular and ECM FN) or acellular (ECM) fractions were analyzed in western blot at indicated dates and increased cell confluence (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A). Representative western blot and quantification of the data is shown. *P < 0.05 in two-tailed t-test ECM versus cellular fraction, means + SD, n = 2. (C) HUVECs were plated for 7 days on gelatin-coated cover classes and FN produced by the cultured cells was stained in intact HUVECs (cells and ECM) and in acellular ECM fraction after removal of the cells using alkaline lysis. In TIE2-WT ordered fibrillar FN strands are evident (arrows). In contrast in Y897F-R915L majority of FN staining is observed within the cells while in the ECM fraction no FN fibrils are stained. Oval structures are nuclei (DAPI, arrow head). (D) Pharmacological inhibition of Erk normalizes FN protein level which is not explained by the FN mRNA expression. *P < 0.05 versus Y897F-R915L, Ctrl and Erk-i, n = 4. (A and D) ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test, means + SD. Scale bars; A, 100 μm; C, 25 μm.

Previous studies have indicated that TIE2/Ang signaling controls EC–ECM interplay (13–15,32,33). In addition, alterations in endothelial ECM composition, including autocrine FN (34), can induce a cellular morphology that closely resembles what we observe with TIE2 mutants. In cultured cells, FN synthesis and ECM deposition are coupled to the establishment of cell–cell junctions and cell confluence (35,36). In order to investigate if the aberrant monolayer morphology is accompanied by altered FN, amounts of FN protein were analyzed at different stages of cell confluence in cellular and acellular (ECM only) fractions (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A). This revealed that ECM FN, but not cellular FN, was diminished when Y897F-R915L reached confluence and practically lost at later stages of confluence. In line with western blotting result, immunostaining (Fig. 5C) showed abundant FN fibrils in the TIE2-WT ECM. In Y897F-R915L, in contrast, FN staining in the ECM was extremely weak and fragmented, with most of the signal located in the cells, possibly representing newly synthesized protein. Reduced ECM FN protein was also observed in the most common somatic (L914F) and germline (R849W) mutations, indicating a common defect (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B). Reduced ECM FN protein, however, did not correlate with its mRNA level (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4C), suggesting increased FN protein degeneration and/or decreased ECM deposition.

To determine whether diminished FN causes loss of normal EC monolayer morphology, FN was knocked down in TIE2-WT HUVECs. This resulted in loss of cobblestone morphology (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4D) closely resembling that of the TIE2-mutant monolayer phenotype. Finally, to confirm that normalization of Y897F-R915L monolayer morphology (Fig. 5A and B) by Erk1/2 inhibition was accompanied by increased FN, the ECM fraction of Erk-inhibited Y897F-R915L HUVECs was analyzed (Fig. 5D). Inhibition of Erk efficiently increased ECM FN levels in the mutant TIE2 expressing HUVECs, but did not significantly increase FN mRNAs.

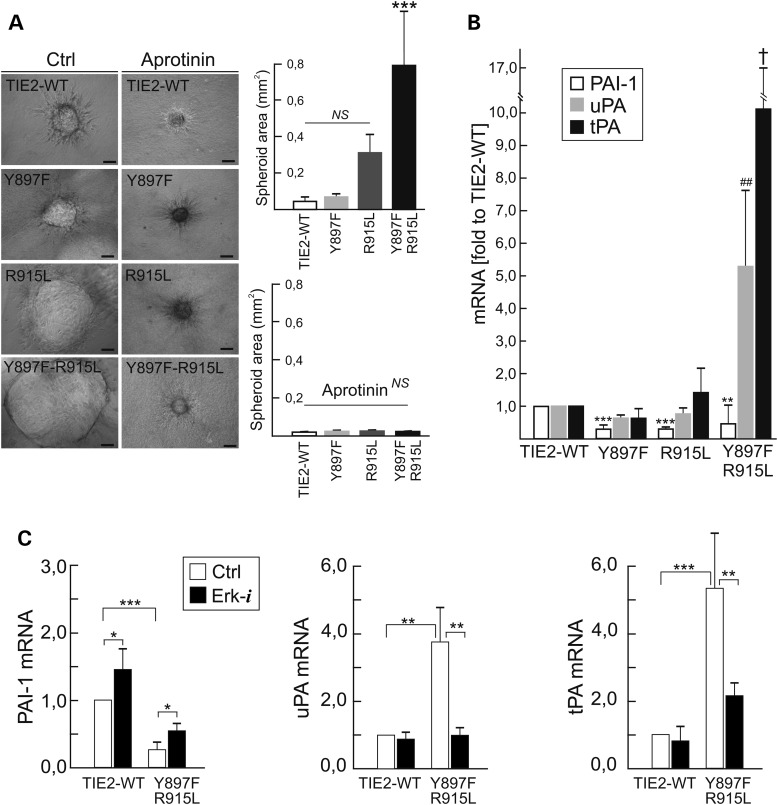

Mutant TIE2 forms activate proteolytic activity of the plasminogen system

We assessed for potential proteolytic pathways activated by mutant-induced Erk signaling, using a fibrin gel model for angiogenesis (37). In fibrin gels, TIE2-WT EC spheroids showed sprouting activity and a low increase in volume during culture (Supplementary Material, Movie S2). In striking contrast, mutant EC spheroids expanded radially to form large thin-walled structures with few sprouts (Supplementary Material, Movie S3). When spheroid areas were measured after 16 h, Y897F-R915L showed markedly larger structures, while Y897F and R915L alone had milder effects (Fig. 6A). The expansion of mutant spheroids was completely blocked by the serine protease inhibitor aprotinin. Urokinase type plasminogen activator (uPA) and tissue type plasminogen activator (tPA), mRNA levels of both of which were strongly upregulated in Y897F-R915L cells, represent potentially relevant targets of aprotinin action; inversely, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) was downregulated (Fig. 6B). Comparisons of Y897F-R915L with the single constituent Y897F and R915L showed a strong synergistic effect on uPA and tPA mRNA increase. Dysregulation of plasminogen activators and PAI-1 was dependent on mutant-TIE2-induced MAPK activity, because a Mek1/Erk1/2 inhibitor (PD98059) normalized expression of uPA, diminished tPA expression to near normal levels and increased PAI-1 expression (Fig. 6C). tPA, uPA and PAI-1 mRNAs were also dysregulated in the most common somatic L914F (PAI-1 57.6 ± 24.3%, P = 0.002; tPA 370.6 ± 190.0%, P = 0.006; uPA 139.4 ± 38.2%, P = 0.08; versus TIE2-WT in two-tailed Student's t-test, means ± SD, n = 6) and germline R849W (PAI-1 84.7 ± 18.6%, P = 0.07; tPA: 190.9 ± 81.7%, P = 0.02; uPA: 139.4 ± 38.2, P = 0.03 versus TIE2-WT in two-tailed Student's t-test, means ± SD, n = 5), that also resulted spheroid expansion in fibrin gel (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4E), thus indicating a common change.

Figure 6.

Mutant TIE2 EC spheroids expand in fibrin gels due to activation of the plasminogen/plasmin proteolytic and MAPK signaling pathways. (A) EC spheroids were embedded into fibrin gels with or without plasmin/serine protease inhibitor aprotinin and areas of spheroids were measured after overnight culturing from phase-contrast microscopy images. Means + SD, ***P < 0.001 versus other cell lines in ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test, n = 3 for control, n = 2 in aprotinin treatment, at least five spheroids were measured for every experiment. Scale bar 100 µm. (B) mRNA expression of PAI-1, uPA and tPA. ***P < 0.001 versus TIE2-WT, **P < 0.01 versus TIE2-WT, ##P < 0.01 versus other cell lines, †P < 0.01 versus TIE2-WT or Y897F in ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test, means + SD, n = 3. (C) Expression of PAI-1, uPA and tPA mRNAs after 7 days culturing with Erk-inhibitor. Inhibition of Erk normalizes plasminogen activation in mutant cells. Means + SD, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 between indicated conditions in two tailed t-test, n = 3.

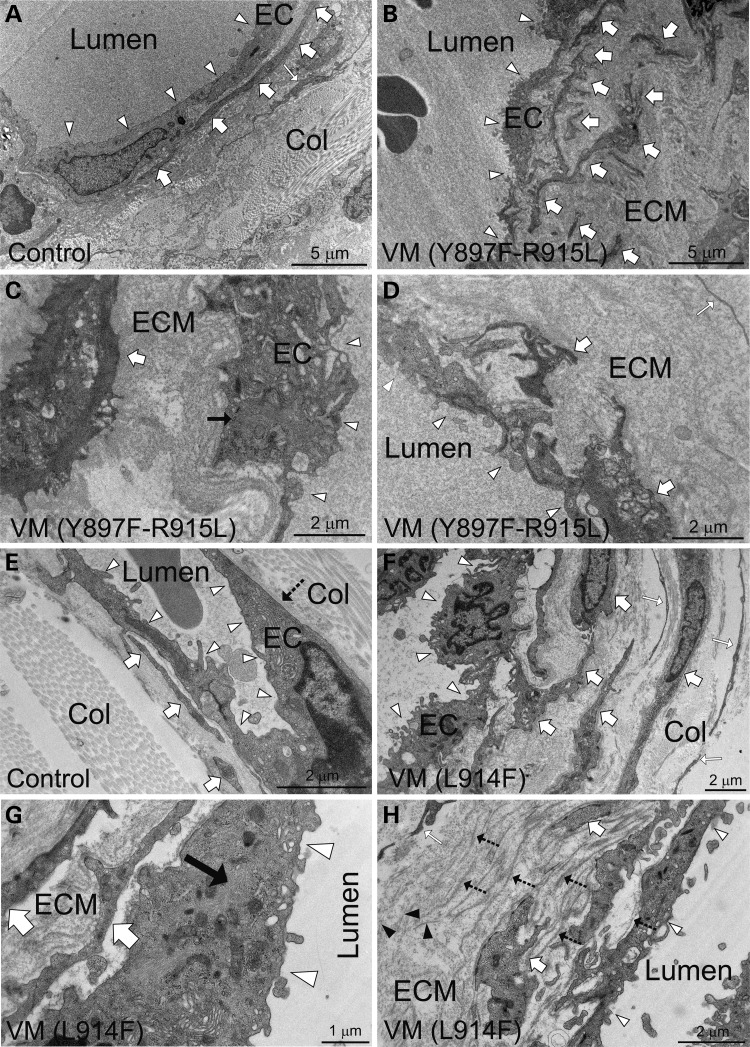

Ultrastructural analysis of lesions shows VM-characteristic changes in perivascular ECM and EC morphology

In cultured HUVECs, we observed a prominent change in endothelial cell morphology, loss of ECM FN and an increase in the extracellular plasmin protease system in response to TIE2 mutations. To investigate EC morphology and ECM in VM lesions, biopsies from patients carrying Y897F-R915L and L914F were investigated using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 7) and focused ion beam and scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) for 3D reconstruction (Supplementary Material, Movies S4 and S5). When compared with nonaffected tissue adjacent to VM lesions (Fig. 7A) and tissues from healthy volunteer donors (Fig. 7E), EC lining in VMs (Fig. 7B–D and F–H) was found to be uneven and characterized by cellular elongations. In ECs where normal endothelial morphology was lost, ultrastructural characterization revealed an increase in EC cytoskeletal filaments, which were not correctly aligned within the cells. In addition, profound changes in the perivascular ECM were observed. These included a very wide layer of basement membrane (BM) material resembling ECM, with randomly oriented and isolated collagen fibrils and erratically distributed smooth muscle cells (SMCs). In focal areas, multilayered BM structures were evident and often occurred with groups of abnormally aggregated perivascular cells. These data indicate that TIE2 mutations cause profound alterations in EC shape and perivascular ECM in patients, as in retrovirally transduced HUVECs.

Figure 7.

TEM analysis of human VM lesions reveals aberrant perivascular ECM and changes in EC morphology and cytoskeleton. (A) Electron micrograph of a normal sized vein (ileum) from healthy tissue adjacent to localized VM lesion shows even endothelium (arrowheads), SMCs (thick white arrows) closely located and aligned with ECs and organized fibrillar collagen matrix (Col) and fibroblasts (white thin arrow). (B–D) Ultrastructural characterization of abnormally enlarged Y897F-R915L vessels (ileum) reveals (B) uneven endothelium (EC, arrowheads) containing cellular extensions and randomly distributed SMCs (thick white arrows). (C) Higher magnification reveals an increase in intermediate filaments in EC cytoskeleton (black arrow) and (D) abnormally thick basement membrane resembling amorphous perivascular matrix (ECM). (E) Skin biopsy of a healthy person and (F–H) VM lesion from the lip. In control endothelium (EC, arrowheads) is relatively even, SMCs are closely aligned (thick white arrows) to ECs and the perivascular fibrillar collagen matrix (Col) is clearly distinguishable. In a L914F VM biopsy endothelium is uneven (F, arrowheads), SMCs (thick white arrows) are disordered, and there is an increase in cytoskeletal filaments randomly oriented through the cytoplasm (G, black arrow). (H) Analysis of perivascular matrix revels randomly orientated sparse collagen fibrils (black arrow-heads) and abnormally multilayered BMs (dashed arrows), likely produced by focally accumulated and misaligned SMCs.

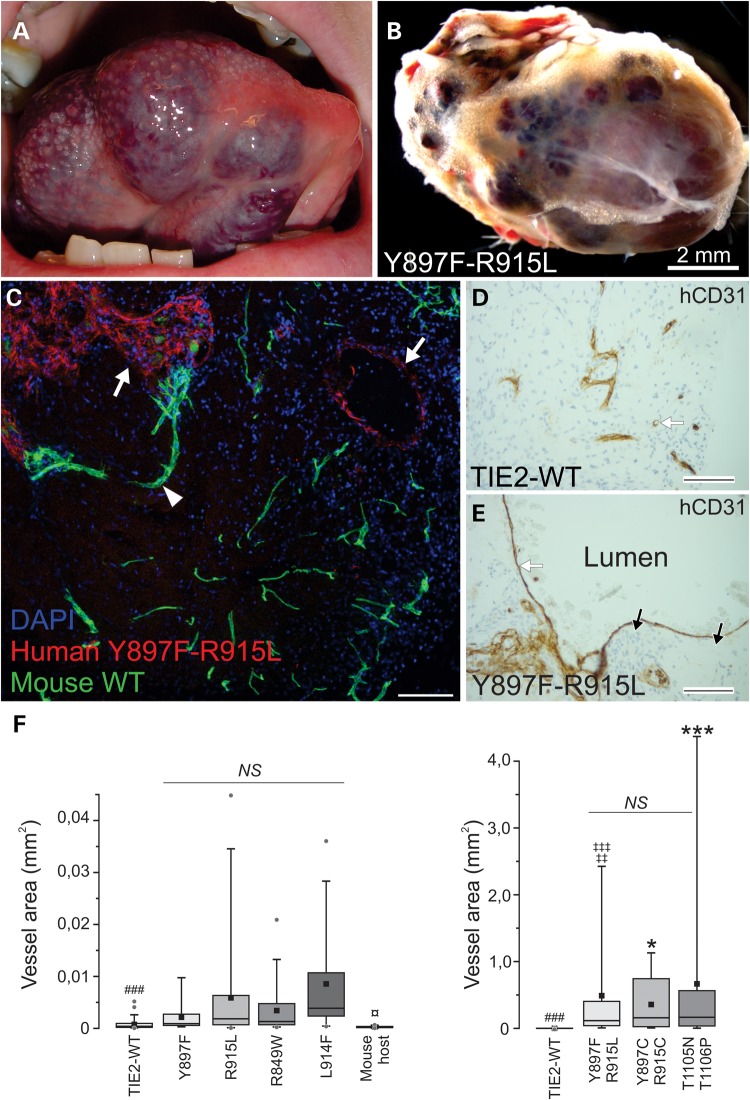

Spheroid-based endothelial cell transplantation in mice recapitulates pathognomonic features of VM lesions and reveals mutation-specific effects

We next tested the capacity of mutated TIE2 expressing HUVECs to form lesions in vivo in a VM mouse model. Previous genetic studies (4,5,7) have suggested that certain TIE2 substitutions have a predisposing rather than disease-causing effect, i.e. these mutations are detected in combination with other mutations. We therefore compared double-mutation Y897F-R915L with the constituent single mutations Y897F and R915L. In addition, we included inherited R849W (that requires a somatic second-hit to cause cutaneomucosal VM (4)) and somatic L914F (that causes >80% of sporadic TIE2-positive VMs). For comparison, we included T1105N-T1106P and Y897C-R915C double-mutations.

Based on macroscopic examination, vascularized plugs closely resembled human VM lesions (Fig. 8A and B and Supplementary Material, Fig. S5) and in histological sections, pathognomonic enlargement in vessel size was evident (Fig. 8C–E). To compare the capacity of TIE2 forms to form enlarged vessels, we quantified the maximal cross-sectional area from the two largest vein-like channels per histological section (Fig. 8F) and qualitatively evaluated (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6) the VM characteristics we identified in ultrastructural characterization of human lesions (Fig. 7).

Figure 8.

VM lesion growth in a mouse transplantation assay. (A) VM lesion on the tongue of a patient and (B) vascularized plug from EC-spheroid implanted mouse. Vascular structures in a mouse model macroscopically resemble human VM lesions. (C) Transplanted human-derived mutant ECs (red) were distinguished from mouse host vasculature (green) using species-specific CD31 antibodies. Scale bar 100 μm. (D and E) Immunohistochemical staining of sections from vascularized TIE2-WT and Y897F-R915L plugs using endothelial anti-human CD31 antibodies (hCD31) with nuclear staining with hematoxylin. When compared with the capillary-sized vessels in WT, vascular lesions showed a pathognomonic increase in vessel size (white arrows) and patchy perivascular cells (black arrows indicating nuclei). Scale bar 100 μm. (F) Maximal vessel area was quantified from histological sections. Two biggest vessels/sections were imaged and area measured using ImageJ. Double-mutated TIE2 expressing HUVECs formed notably large structures, displayed in the graph on the right (note different y-axis scaling for single and double-mutants). 25th quartile, median, 75th quartile (box), average (square), 5th and 95th percentile (whiskers) and outliers (dot) are shown. P < 0.001 in Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance (all groups in both graphs included). Pairwise comparisons were performed with Mann–Whitney U-test and thresholds of significant P-values were adjusted with Bonferroni correction for 36 pairwise comparisons. n = 13–54, each vessel was counted as an observation. Mouse host ECs formed capillary-sized vessels and were smaller than in other groups (¤P < 0.05). R915L, L914F and double-mutants formed statistically significantly larger vessels than TIE-WT (###P < 0.001) and Y897F-R915L showed a clear enlargement in vessel size compared with single constituent mutations (‡‡P < 0.01 versus Y897F, ‡‡‡P < 0.001 versus R915L). Other double-mutations induced similar vessel enlargement (***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05 versus single mutations). NS, statistically non-significant.

When no HUVEC spheroids were added to plugs, capillary-sized vessels derived from the mouse host vasculature were formed. TIE2-WT HUVECs formed relatively small-sized vessels (maximum cross-sectional area, 5169 μm2; median value, 404 μm2). In addition, TIE2-WT vascular structures showed little variation in EC morphology, and mouse-derived SMCs were aligned closely with the vessels and formed a single layer. Filaments in the TIE2-WT EC cytoskeleton were not prominent and were mostly aligned parallel to the longitudinal axis of the cells (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6A).

R849W (maximum cross-sectional area, 20 861 μm2, median 1313 μm2) contained some abnormally enlarged vessels when compared with the TIE2-WT. Ultrastructure showed patchy SMC layering, and relatively mildly affected EC morphology and close-to-normal perivascular ECM (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6E). In L914F, vessel enlargement was more pronounced (maximum cross-sectional area, 35 984 μm2, median 3865 μm2) and ultrastructure showed patchy SMC layering, prominent EC cytoskeleton and multilayered BMs (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6F).

When single constituent mutations (Y897F, R915L) were compared with the resulting Y897F-R915L double-mutation, a clear enlargement in vessel area was evident (60 times as large as constituent single mutation, median 115 548 μm2), indicating a synergistic effect. EC morphology was more severely altered in the double-mutant, showing an irregular appearance. Perivascular cells were not correctly aligned with the vessels; instead, they were either focally absent or present in multiple disordered layers (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6D). In the perivascular ECM, isolated and randomly oriented collagen fibers and abnormally wide BM-like material were evident, closely resembling changes observed in the Y897F-R915L positive VM biopsy from a patient (Fig. 7B–D). Y897F alone resulted in a relatively small increase in vessel size (maximum cross-sectional area, 9732 μm2; median 904 μm2) and showed focal areas of patchy SMCs (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6B). R915L resulted in larger vessel size (maximum cross-sectional area, 44 758 μm2; median 1839 μm2), patchy SMC covering, higher variation in EC morphology and some changes in the perivascular ECM (thick BM-like material, with some isolated and randomly oriented collagen fibers) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S6C). As in Y897F-R915L, a high capacity to form VM lesions was also observed with the other double-mutants tested, T1105N-T1106P and Y897C-R915C (Fig. 8F and Supplementary Material, Fig. S5).

To investigate the cellular mechanisms that may relate to the growth of abnormally enlarged vessels, we measured cell length, and the extent of apoptosis and proliferation in TIE2-WT and Y897F-R915L vascular structures using TEM micrographs and immunohistological staining, respectively. In previous publications, common germline (R849W) and somatic (L914F) TIE2 mutations were found to increase EC resistance to apoptosis but not induce cell proliferation in culture (6,38). In line with these results, in Y897F-R915L-containing vascular structures, we observed p53-positive nuclei less frequently than in TIE2-WT (1.05 ± 0.47 nuclei/100 μm versus 1.63 ± 0.61 nuclei/100 μm, means ± SD, n = 20, P < 0.01, two-tailed t-test), without an increase in cell proliferation (0.55 ± 0.32 Ki67 positive nuclei/100 μm versus 0.59 ± 0.52 nuclei/100 μm, means ± SD, n = 20, P = 0.79). In Y897F-R915L-containing vessels, ECs (22.3 ± 16.3 μm, n = 61) were twice as long as in TIE2-WT vessels (11.0 ± 7.23 μm, n = 68, P < 0.001). EC elongation may contribute to increased vessel diameter of VM lesions in the absence of EC proliferation, as proposed for enlarged vessels in arteriovenous malformations (39); it may also be secondary to loss of ECM support.

Discussion

VMs are pathological errors of vascular morphogenesis. About 50% of the lesions are TIE2 mutation positive (4,5,7). Common to all TIE2 mutations is increased phosphorylation (activation) to variable degrees; however, with the exception of the common (germline) R849W and (somatic) L914F, cellular and molecular alterations caused by other mutant forms of TIE2 have not been previously investigated in ECs.

In this study, we compared 22 TIE2 mutations in a comprehensive manner in HUVECs, using biochemical and cell biological assays, VM mouse model and tissue biopsies resected from VM patients. We observed alterations that were common to disease-causative mutations, but also divergent cellular and molecular effects that fall into certain categories in hierarchical clustering analysis (Supplementary Material, Fig. S7): Y897-containing double-mutations, T1105N-containing double-mutations and Y897-single mutations. Inherited R849W clusters with the Y897 single mutations (and relatively close to TIE2-WT), supporting its status as a ‘predisposing’ (rather than causative) mutation that requires an additional (somatic) change to cause disease. This is further strengthened by the VM mouse model, in which both Y897F and R849W showed low VM-formation capacity.

Ang1-ligand-stimulated TIE2 is compartmentalized and activated in specific subcellular domains where it induces location-dependent downstream signaling (13–15). TIE2 trafficking (the subcellular site of activation and/or ligand-induced receptor clustering and translocation) was found to be frequently abnormal (in 95% of mutations studied). Detailed analysis indicated that TIE2 mutations reduce plasma membrane located TIE2 via various mechanisms: in the case of Y897F-R915L, we found accelerated turnover rate and increased shedding of TIE2 extracellular domain. This increases the amount of soluble (shed) TIE2, which may exert an additional inhibitory effect by competing for ligand with membrane-bound TIE2 receptor. The common L914F mutation instead causes intracellular accumulation possibly due to incomplete glycosylation and increased clustering. Interestingly, this occurred independently of mutant-induced increases in TIE2 P-Tyr level. Thus, mutations in TIE2, via different mechanisms, may reduce TIE2 function as a cell membrane receptor for angiopoietins. This would suggest that, in addition to chronically increased, aberrant signaling, mechanisms that silence extracellular ligand-controlled TIE2 functions might potentiate VM development. Indeed, the first demonstration of a somatic second-hit in VMs was in a lesion from a patient carrying the R849W germline mutation and consisted of a deletion in trans (i.e. in the WT allele) that caused localized loss of WT TIE2 function (4).

At confluence, normal ECs form an epithelial-like monolayer with typical cobblestone morphology. This was lost, to varying degrees, by expression of TIE2-VM mutations in culture, thus representing a common defect. In addition, a characteristic feature of endothelium in the patient and VM mouse-derived lesions was loss of normal EC morphology. We found that this feature was dependent on mutant TIE2 kinase activity and occurred via Erk1/2 dependent loss of FN. FN interacts with and functions as a scaffold for proper assembly of many ECM and BM components (40). It also binds endothelial α5β1 integrin and potentiates TIE2 signaling induced by Ang1-ligand (41). In gene-targeted mouse embryos, lack of FN results in defective morphogenesis including dilated and malformed vessels and loss of endothelial–mesenchymal contact (42). This suggests that a decrease in FN, due to uncontrolled TIE2 activation, may have a role in formation of VM lesions.

In addition to FN depletion, we observed other aberrant ECM features such as a poorly organized fibrillar collagen matrix and altered BM layering in affected mouse and patient tissues. This may be linked to induction of the plasmin proteolytic system (upregulation of uPA and tPA, downregulation of PAI-1 mRNAs) by TIE2 mutants. In addition to fibrinolysis, plasmin can directly degrade many ECM proteins including FN and BM laminin and can induce activation of various pro-matrix metalloproteinases that degrade ECM components (43–47). In addition, mRNA expression profiling revealed that L914F strongly increases the expression of ADAMTS peptidases that are also involved in perivascular ECM modeling (6). The increase in ECM protease activity and aberrant ECM in VM lesions may destabilize the vascular wall, decreasing mechanical support and thereby contributing to the development of abnormally expanded venous channels. Indeed, the formation of abnormally expanded spheroids by mutant HUVECs is similar to that previously reported for increased fibrinolytic activity in ECs (48,49) and is prevented by treatment with the plasmin/serine protease inhibitor aprotinin. Importantly, mutant TIE2-induced activation of the plasminogen/plasmin protease system also most likely plays a role in coagulopathy in the form of high serum d-dimers (a fibrin degradation product), commonly observed in VM patients (9–12).

Akt activation is linked to increased survival of ECs and mutant TIE2-induced P-Akt decreased EC secretion of SMC attractant, PDGFB, via the transcription factor FOXO1 (6). In a very recent study rapamycin (a mTOR protein kinase inhibitor) reduced TIE2 mutation-induced P-Akt in cultured ECs and VM lesion size in immune-deficient nu/nu mice and also improved symptoms in six severely affected VM patients (50). Interestingly, rapamycin can increase PAI-1 and decrease tPA expression (51) and in clinical pilot study (50) rapamycin treatment reduced d-dimer levels in three out of five patients. However, in clinical use long-term rapamycin treatment may cause significant side-effects, it has potent immunosuppressant actions and rapamycin reduced volumes of existing VM lesion only slightly. In addition, commercially available TIE2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor showed no effect on VM growth in mice (50), thus making the identification of TIE2 VM-specific molecular and cellular pathways necessary for the development of better treatments.

Taken together, our data suggest that formation of VMs by TIE2 mutations relies on several molecular mechanisms that occur in tandem: (additive/synergistic effects of single mutations) on Akt activation, which reduces the major EC-secreted SMC-attractant PDGFB (6); loss of plasma membrane TIE2, which results in lower responsiveness to angiopoietin ligand-mediated regulation; and Erk1/2 activation, which negatively impacts EC morphology and ECM FN and dysregulates the plasminogen/plasmin coagulation cascade. The VM-characteristic phenotypes these pathways mediate in patients are recapitulated in a spheroid-transplantation mouse model. It therefore represents a faithful yet flexible animal model in which to test therapies against the gamut of VM mutations.

Materials and Methods

Institutional and licensing committee approving the mice experiments

Experiments involving mice were performed under permissions from the National Animal Experiment Board of Finland following the regulations of the EU Directive 86/609/EEC, the European Convention ETS123 and national legislation.

Human subjects

The investigation conformed to the principles set out in the WMA Declaration of Helsinki and the Department of Health and Human Services Belmont Report. VM tissue samples were removed by surgery, and the protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Medical Faculty of the Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Reagents and cell culture

HUVECs were cultured in Endothelial Cell Basal Medium (ECBM, Cell Applications Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS and growth supplements provided by the manufacturer. 293-GPG-VSV-G packaging cells (52) were transfected for retrovirus production with Fugene HD Transfection Reagent (Promega). TIE2 cDNA constructs containing different mutations were cloned into pMXs and pMXs-IRES-GFP vectors (53). FN shRNA construct (TRCN0000064831) was acquired from RNAi consortium shRNA library (http://www.broadinstitute.org/rnai/trc). For some experiments, cells were stimulated with recombinant Ang1 (R&D Systems) or inhibited with PI3 Kinase inhibitor (LY294002; Cell Signaling) or MEK1 inhibitor (PD98059; Cell Signaling).

Cell and ECM lysis, immunoprecipitation, western blotting

Cells were changed into 2% FBS media and incubated overnight. The next day cells were lysed in cell lysis buffer (9.1 mm Na2HPO4, 1.7 mm NaH2PO4, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1 mm EDTA) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (P8340 and P5726, Sigma-Aldrich). To extract ECM proteins, without prior serum starvation cells were removed by washing plates first once with 0.05% Triton-X100 and 50 mm NH4OH in PBS, then once with 50 mm NH4OH and three times with PBS after which ECM proteins were extracted using cell lysis buffer including 6.5 m urea. For immunoprecipitation of TIE2, whole cell lysates were incubated overnight in rotation at +4°C with agarose conjugated TIE2 antibody (sc-324 AC, Santa Cruz), then washed three times with RIPA buffer and boiled for 5 min with 1% 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich).

For western blotting proteins were separated with SDS-PAGE and transferred into nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking in 1% BSA or 5% milk powder in 0.05% Tween-PBS for 1 h, membranes were incubated with primary antibody dilution overnight at +4°C. Horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) with Lumi-light Western blotting substrate (Roche) were used to detect protein bands using LAS 3000 luminescent image analyzer (Fujifilm). For reprobing with different primary antibody, membranes were stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Thermo Scientific) and blotted as detailed above. For certain experiments, plasma membrane protein samples were generated using Cell Surface Protein Isolation Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to manufacturer's instructions. Four confluent 100 mm dishes were used for each sample. Band densities were analyzed with Quantity One 1D gel analysis software (Bio-Rad) and normalized to actin (cell lysates) or total protein (ECM lysates, BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Scientific).

TIE2 ELISA and protein synthesis inhibition

Amount of TIE2 in cell lysates and soluble TIE2 in conditioned cell culture media was measured using DuoSet ELISA Development kit for human TIE2 (R&D systems) according to manufacturer's protocol. ECs were first changed to fresh ECBM media and after 24 h cells were lysed and media samples collected for ELISA analysis. Cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to block protein synthesis in cells to study TIE2 turnover. After up to 24 h incubation in cycloheximide (20 µg/ml), cells were lysed and TIE2 measured with ELISA and results normalized to total protein concentration quantified using BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Quantitation of cell morphology

To quantitate number of cell extensions, 150 000 cells/6-well were seeded and cultured in standard conditions for 5 days to reach late confluence. Ten pictures per dish or well were captured using a phase-contrast microscope and frequency of cells with thin cell extensions overlapping neighboring cells was manually counted from digitized images as an positive indication. The average number of extensions in a plate (calculated from 10 randomly chosen pictures per plate) was used as a single observation. Minimum of three independent experiments were performed for every cell line. For certain experiments, cells were first cultured on 60 mm culture dishes until early confluence and then with recombinant Ang1 (500 ng/ml) or MEK1 inhibitor (10 µM) for up to 7 days with fresh media containing the inhibitor/ligand changed every second day. In the end wells were imaged and extensions quantified as described above.

Intracellular retention analysis

For glycosylation analysis, total cell lysates were treated with Endo-H (New England Biolabs) or PNGase F (New England Biolabs) according to manufacturer's protocol before western blotting. For intracellular dimerization and clustering experiments, the Fc tail of IgG was cloned to the C-terminus of full-length TIE2-WT. HUVECs were transduced with retroviruses containing TIE2-WT_Fc or separately with TIE2-WT and Ang1. Location of TIE2 was analyzed by immunostaining and fluorescence confocal microscopy as explained in Supplementary Material, Supplemental Materials and Methods (immunofluorescence staining).

VM-lesion formation in mice

Mouse model was based on endothelial transplantation assay where ECs are grafted into SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency) mice as spheroids (54). HUVECs transduced with bicistronic pMXs-IRES-GFP retrovirus (35) carrying WT or mutant TIE2-forms and selected for GFP using flow cytometer were suspended into 10% FBS and growth factor supplemented ECBM containing 0.24% methylcellulose (wt/vol, Sigma-Aldrich), pipetted as drops to nonadherent petri dishes (Greiner) and incubated as hanging-drops overnight to form EC-spheroids of 1000 cells. The next day spheroids were collected, washed, divided into tubes (1000 spheroids/1.0 × 106 cells per tube) and suspended to 300 µl of ECBM/fibrinogen/methocel solution (1:1:1) containing 1 µg/ml VEGF (ReliaTech) and FGF-2 (ReliaTech). Before injection 300 µl of growth factor reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and 4 U of thrombin (Calbiochem) were added per tube, solution mixed and immediately injected to flank of 6–8 weeks old female SCID mice (C.B-17 scid, Taconic). Each mouse was injected to both flanks each with 1000 spheroids. After 10 days mice were sacrificed, plugs dissected out from mice, imaged with stereomicroscope and samples collected for histological, immunofluorescence and ultrastructural analyses from each plug. At least four plugs per each mutant cell line and non-HUVEC control and eight plugs for TIE2-WT were analyzed. Mice were maintained in individually ventilated cages (IVC) as experimental groups of four mice and handled with sterile procedures.

Fibrin gel assay

EC spheroids were generated and collected as described in the previous section (VM-lesion formation in mice) with the difference that 500 cells/spheroid were used. Approximately 50 spheroids per tube were suspended in 400 µl of supplemented culture media containing 10% FBS, 3 mg/ml fibrinogen and 0.24% methylcellulose and pipetted to 24-well with 1 U thrombin in the bottom of the well. Gel was let to polymerize in 37°C for 1 h before 500 µl media were added on top. In serine protease inhibition assays both the gel and media were supplemented with 25 µg/ml aprotinin (Sigma-Aldrich). After 16 h cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and imaged for quantification using a phase-contrast microscope. Spheroid areas were quantified using ImageJ by manually drawing borders of the spheroids' core. At least five spheroids per experiment were measured and average used as single observation in final analysis. Cell sprouts extending out from spheroid were not included in the area measurement.

Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples from VMs formed in SCID mice were fixed with 10% formalin and embedded into paraffin. Then, 5 µm sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin–eosin. For immunohistochemistry, 3.5 µm were cut, de-paraffinized in xylene and rehydrated with graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was performed with Tris–EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) in a microwave oven at 800 W for 2 min and at 150 W for 15 min after which slides were incubated with primary antibody (CD31, p53 or Ki67 from BD Pharmingen, Dako and Novocastra, respectively). Bound antibodies were detected using the EnVision system (Dako). To quantify maximal vessel area, two largest veins/sample sections were imaged and area measured using ImageJ. For apoptosis and proliferation measurement, veins from p53 and Ki67 stained sections were imaged, positive nuclei counted and vessel wall lengths measured using ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with OriginPro 9.1 using unpaired or paired two-tailed Student's t-test, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test or Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric ANOVA followed by Mann–Whitney U-test with Bonferroni correction for pairwise comparisons. Hierarchical clustering was performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 20 using the between-groups linkage method with Pearson correlation to calculate the distances.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Academy of Finland (136880 and Centre of Excellence Program 2012–2017 to L.E.); Finnish Cultural Foundation (00140680 to MN), the Belgian Science Policy Office Interuniversity Attraction Poles (IAP P7/43-BeMGI to M.V.); the National Institute of Health (P01 AR048564 to M.V.) and the F.R.S.-FNRS (Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique). We also thank la Communauté française de Wallonie-Bruxelles and la Lotterie nationale, Belgium, for their support. J.S. was supported by a Pierre M. fellowship and by Télévie, and N.L. is a Chercheur Qualifié du F.R.S-FNRS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Jaana Träskelin and Riitta Jokela for expert technical assistance and Center of Microscopy and Nanotechnology of University of Oulu for the access to FIB-SEM and application engineer Esa Heinonen for help in operating the instrument.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Dompmartin A., Vikkula M., Boon L.M. (2010) Venous malformation: update on aetiopathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Phlebology, 25, 224–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boon L.M., Vikkula M. (2012) Vascular malformations. In Lowell A., Goldsmith S. I., Katz B. A., Gilchrest A. S., Paller D. J., Leffell K.W. (eds), Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. McGraw-Hill Professional Publishing, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soblet J., Limaye N., Uebelhoer M., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. (2013) Variable somatic TIE2 mutations in half of sporadic venous malformations. Mol. Syndromol., 4, 179–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Limaye N., Wouters V., Uebelhoer M., Tuominen M., Wirkkala R., Mulliken J.B., Eklund L., Boon L.M., Vikkula M. (2009) Somatic mutations in angiopoietin receptor gene TEK cause solitary and multiple sporadic venous malformations. Nat. Genet., 41, 118–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wouters V., Limaye N., Uebelhoer M., Irrthum A., Boon L.M., Mulliken J.B., Enjolras O., Baselga E., Berg J., Dompmartin A. et al. (2010) Hereditary cutaneomucosal venous malformations are caused by TIE2 mutations with widely variable hyper-phosphorylating effects. Eur. J. Hum. Genet., 18, 414–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uebelhoer M., Nätynki M., Kangas J., Mendola A., Nguyen H.-L., Soblet J., Godfraind C., Boon L.M., Eklund L., Limaye N. et al. (2013) Venous malformation-causative TIE2 mutations mediate an AKT-dependent decrease in PDGFB. Hum. Mol. Genet., 22, 3438–3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vikkula M., Boon L.M., Carraway K.L., Calvert J.T., Diamonti A.J., Goumnerov B., Pasyk K.A., Marchuk D.A., Warman M.L., Cantley L.C. et al. (1996) Vascular dysmorphogenesis caused by an activating mutation in the receptor tyrosine kinase TIE2. Cell, 87, 1181–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shewchuk L.M., Hassell A.M., Ellis B., Holmes W.D., Davis R., Horne E.L., Kadwell S.H., McKee D.D., Moore J.T. (2000) Structure of the Tie2 RTK domain—self-inhibition by the nucleotide binding loop, activation loop, and C-terminal tail. Structure, 8, 1105–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dompmartin A., Ballieux F., Thibon P., Lequerrec A., Hermans C., Clapuyt P., Barrellier M.-T., Hammer F., Labbé D., Vikkula M. et al. (2009) Elevated d-dimer level in the differential diagnosis of venous malformations. Arch. Dermatol., 145, 1239–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dompmartin A., Acher A., Thibon P., Tourbach S., Hermans C., Deneys V., Pocock B., Lequerrec A., Labbé D., Barrellier M.-T. et al. (2008) Association of localized intravascular coagulopathy with venous malformations. Arch. Dermatol., 144, 873–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redondo P., Aguado L., Marquina M., Paramo J., Sierra A., Sánchez-Ibarrola A., Martínez-Cuesta A., Cabrera J. (2010) Angiogenic and prothrombotic markers in extensive 4slow-flow vascular malformations: implications for antiangiogenic/antithrombotic strategies. Br. J. Dermatol., 162, 350–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazoyer E., Enjolras O., Bisdorff A., Perdu J., Wassef M., Drouet L. (2008) Coagulation disorders in patients with venous malformation of the limbs and trunk: a case series of 118 patients. Arch. Dermatol., 144, 861–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuhara S., Sako K., Minami T., Noda K., Kim H.Z., Kodama T., Shibuya M., Takakura N., Koh G.Y., Mochizuki N. (2008) Differential function of Tie2 at cell–cell contacts and cell–substratum contacts regulated by angiopoietin-1. Nat. Cell. Biol., 10, 513–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saharinen P., Eklund L., Miettinen J., Wirkkala R., Anisimov A., Winderlich M., Nottebaum A., Vestweber D., Deutsch U., Koh G.Y. et al. (2008) Angiopoietins assemble distinct Tie2 signalling complexes in endothelial cell–cell and cell–matrix contacts. Nat. Cell. Biol., 10, 527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pietilä R., Nätynki M., Tammela T., Kangas J., Pulkki K.H., Limaye N., Vikkula M., Koh G.Y., Saharinen P., Alitalo K. et al. (2012) Ligand oligomerization state controls Tie2 receptor trafficking and angiopoietin-2-specific responses. J. Cell. Sci., 125, 2212–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim I., Kim H.G., So J.N., Kim J.H., Kwak H.J., Koh G.Y. (2000) Angiopoietin-1 regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3’-Kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Circ. Res., 86, 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoon M.J., Cho C.H., Lee C.S., Jang I.H., Ryu S.H., Koh G.Y. (2003) Localization of Tie2 and phospholipase D in endothelial caveolae is involved in angiopoietin-1-induced MEK/ERK phosphorylation and migration in endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 308, 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kontos C.D., Stauffer T.P., Yang W.P., York J.D., Huang Li., Blanar M.A., Meyer T., Peters K.G. (1998) Tyrosine 1101 of Tie2 is the major site of association of p85 and is required for activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 4131–4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones N., Master Z., Jones J., Bouchard D., Gunji Y., Sasaki H., Daly R., Alitalo K., Dumont D.J. (1999) Identification of Tek/Tie2 binding partners: binding to a multifunctional docking site mediates cell survival and migration. J. Biol. Chem., 274, 30896–30905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lievens P.M.J., Mutinelli C., Baynes D., Liboi E. (2004) The kinase activity of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 with activation loop mutations affects receptor trafficking and signaling. J. Biol. Chem., 279, 43254–43260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabone-Eglinger S., Subra F., El Sayadi H., Alberti L., Tabone E., Michot J.P., Théou-Anton N., Lemoine A., Blay J.Y., Emile J.F. (2008) KIT mutations induce intracellular retention and activation of an immature form of the KIT protein in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin. Cancer Res., 14, 2285–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatch N.E., Hudson M., Seto M.L., Cunningham M.L., Bothwell M. (2006) Intracellular retention, degradation, and signaling of glycosylation- deficient FGFR2 and craniosynostosis syndrome-associated FGFR2C278F. J. Biol. Chem., 281, 27292–27305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contessa J.N., Bhojani M.S., Freeze H.H., Rehemtulla A., Lawrence T.S. (2008) Inhibition of N-linked glycosylation disrupts receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in tumor cells. Cancer. Res., 68, 3803–3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bass J., Chiu G., Argon Y., Steiner D.F. (1998) Folding of insulin receptor monomers is facilitated by the molecular chaperones calnexin and calreticulin and impaired by rapid dimerization. J. Cell. Biol., 141, 637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt-Arras D.-E., Böhmer A., Markova B., Choudhary C., Serve H., Böhmer F.-D. (2005) Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates maturation of receptor tyrosine kinases. Mol. Cell Biol., 25, 3690–3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang L., Turck C.W., Rao P., Peters K.G. (1995) GRB2 and SH-PTP2: potentially important endothelial signaling molecules downstream of the TEK/TIE2 receptor tyrosine kinase. Oncogene., 11, 2097–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurt C.M., Ho V.K., Angelotti T. (2013) Systematic and quantitative analysis of G protein-coupled receptor trafficking motifs. Methods Enzymol., 521, 171–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamakawa D., Kidoya H., Sakimoto S., Jia W., Naito H., Takakura N. (2013) Ligand-independent Tie2 dimers mediate kinase activity stimulated by high dose angiopoietin-1. J. Biol. Chem., 288, 12469–12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bogdanovic E., Nguyen V.P.K.H., Dumont D.J. (2006) Activation of Tie2 by angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 results in their release and receptor internalization. J. Cell. Sci., 119, 3551–3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reusch P., Barleon B., Weindel K., Martiny-Baron G., Gödde A., Siemeister G., Marmé D. (2001) Identification of a soluble form of the angiopoietin receptor TIE-2 released from endothelial cells and present in human blood. Angiogenesis, 4, 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Findley C.M., Cudmore M.J., Ahmed A., Kontos C.D. (2007) VEGF induces Tie2 shedding via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt dependent pathway to modulate Tie2 signaling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol., 27, 2619–2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suri C., Jones P.F., Patan S., Bartunkova S., Maisonpierre P.C., Davis S., Sato T.N., Yancopoulos G.D. (1996) Requisite role of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the TIE2 receptor, during embryonic angiogenesis. Cell, 87, 1171–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeansson M., Gawlik A., Anderson G., Li C., Kerjaschki D., Henkelman M., Quaggin S.E. (2011) Angiopoietin-1 is essential in mouse vasculature during development and in response to injury. J. Clin. Invest., 121, 2278–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cseh B., Fernandez-Sauze S., Grall D., Schaub S., Doma E., Van Obberghen-Schilling E. (2010) Autocrine fibronectin directs matrix assembly and crosstalk between cell–matrix and cell–cell adhesion in vascular endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci., 123, 3989–3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Birdwell C.R., Gospodarowicz D., Nicolson G.L. (1978) Identification, localization, and role of fibronectin in cultured bovine endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 75, 3273–3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen L.B., Gallimore P.H., McDougall J.K. (1976) Correlation between tumor induction and the large external transformation sensitive protein on the cell surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 73, 3570–3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korff T., Augustin H.G. (1999) Tensional forces in fibrillar extracellular matrices control directional capillary sprouting. J. Cell. Sci., 112, 3249–3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris P.N., Dunmore B.J., Tadros A., Marchuk D.A., Darland D.C., D'Amore P.A., Brindle N.P.J. (2005) Functional analysis of a mutant form of the receptor tyrosine kinase Tie2 causing venous malformations. J. Mol. Med., 83, 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy P.A., Kim T.N., Huang L., Nielsen C.M., Lawton M.T., Adams R.H., Schaffer C.B., Wang R.A. (2014) Constitutively active Notch4 receptor elicits brain arteriovenous malformations through enlargement of capillary-like vessels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kostourou V., Papalazarou V. (2014) Non-collagenous ECM proteins in blood vessel morphogenesis and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj., 1840, 2403–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cascone I., Napione L., Maniero F., Serini G., Bussolino F. (2005) Stable interaction between alpha5beta1 integrin and Tie2 tyrosine kinase receptor regulates endothelial cell response to Ang-1. J. Cell Biol., 170, 993–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.George B.E.L., Baldwin H.S., Hynes R.O., George E.L. (1997) Fibronectins are essential for heart and blood vessel morphogenesis but are dispensable for initial specification of precursor cells. Blood, 90, 3073–3081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liotta L.A., Goldfarb R.H., Brundage R., Siegal G.P., Terranova V., Garbisa S. (1981) Effect of plasminogen activator (urokinase), plasmin, and thrombin on glycoprotein and collagenous components of basement membrane. Cancer Res., 41, 4629–4636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baramova E.N., Bajou K., Remacle A., L'Hoir C., Krell H.W., Weidle U.K., Noel A., Foidart J.M. (1997) Involvement of PA/plasmin system in the processing of pro-MMP-9 and in the second step of pro-MMP-2 activation. FEBS Lett., 405, 157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horowitz J.C., Rogers D.S., Simon R.H., Sisson T.H., Thannickal V.J. (2008) Plasminogen activation-induced pericellular fibronectin proteolysis promotes fibroblast apoptosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol., 38, 78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Houard X., Monnot C., Dive V., Corvol P., Pagano M. (2003) Vascular smooth muscle cells efficiently activate a new proteinase cascade involving plasminogen and fibronectin. J. Cell Biochem., 88, 1188–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bonnefoy A., Legrand C. (2000) Proteolysis of subendothelial adhesive glycoproteins (fibronectin, thrombospondin, and von Willebrand factor) by plasmin, leukocyte cathepsin G, and elastase. Thromb. Res., 98, 323–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montesano R., Pepper M.S., Möhle-Steinlein U., Risau W., Wagner E.F., Orci L. (1990) Increased proteolytic activity is responsible for the aberrant morphogenetic behavior of endothelial cells expressing the middle T oncogene. Cell, 62, 435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sabapathy K.T., Pepper M.S., Kiefer F., Möhle-steinlein U., Tacchini-cottier F., Fetka I., Breier G., Risau W., Carmeliet P., Montesano R. et al. (1997) Polyoma middle T-induced vascular tumor formation: the role of the plasminogen activator/plasmin system. J. Cell. Biol., 137, 953–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boscolo E., Limaye N., Huang L., Kang K.-T., Soblet J., Uebelhoer M., Mendola A., Natynki M., Seront E., Dupont S. et al. (2015) Rapamycin improves TIE2-mutated venous malformation in murine model and human subjects. J. Clin. Invest., 125, 3491–3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muldowney J.A.S., Stringham J.R., Levy S.E., Gleaves L.A., Eren M., Piana R.N., Vaughan D.E. (2007) Antiproliferative agents alter vascular plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression: a potential prothrombotic mechanism of drug-eluting stents. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol., 27, 400–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ory D.S., Neugeboren B.A., Mulligan R.C. (1996) A stable human-derived packaging cell line for production of high titer retrovirus/vesicular stomatitis virus G pseudotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 11400–11406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kitamura T., Koshino Y., Shibata F., Oki T., Nakajima H., Nosaka T., Kumagai H. (2003) Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer and expression cloning: powerful tools in functional genomics. Exp. Hematol., 31, 1007–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laib A.M., Bartol A., Alajati A., Korff T., Weber H., Augustin H.G. (2009) Spheroid-based human endothelial cell microvessel formation in vivo. Nat. Protoc., 4, 1202–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.