Abstract

Extravagant male ornaments expressed during reproduction are almost invariably assumed to be sexually selected and evolve through competition for mating opportunities. Yet in species where male reproductive success depends on the defence of offspring, male ornaments could also evolve through social competition for offspring survival. However, in contrast to female ornaments, this possibility has received little attention in males. We show that a male ornament that is traditionally assumed to be sexually selected—the red nuptial coloration of the three-spined stickleback—is under stronger selection for offspring survival than for mating success. Males express most coloration during parenting, when they no longer attract females, and the colour correlates with nest retention and hatching success but not with attractiveness to females. This contradicts earlier assumptions and suggests that social selection for offspring survival rather than for sexual selection for mating success is the main mechanism maintaining the ornament in the population. These results suggest that we should consider other forms of social selection beyond sexual selection when seeking to explain the function and evolution of male ornaments. An incorrect assignment of selection pressures could hamper our understanding of evolution.

Keywords: mate choice, social selection, parental care, offspring survival, signals

1. Introduction

Sexual selection for improved mating and fertilization success is generally considered the cause of the evolution and maintenance of male ornaments expressed during reproduction [1,2]. However, an alternative possibility, which has received surprisingly little attention (but see [3,4]), is that male ornaments evolve through social competition for offspring survival. This mechanism falls outside the usual definition of sexual selection, and is often classed as a form of ‘non-sexual social selection’ (hereafter ‘social selection’) [5,6]. Male ornaments can then function as badges of status that allow males to resolve conflicts without resorting to costly fights, which in turn can improve current or future reproductive success [7–9]. Second, ornaments could be adopted as indicators of mate quality in mate choice, or of competitive ability in the competition for females, and be favoured by sexual selection for improved mating and fertilization success [10,11]. Yet teasing apart the relative importance of sexual and social selection in driving the evolution of the ornaments can be difficult [12]. This has resulted in all selection related to reproduction sometimes being referred to as sexual selection. However, this can result in faulty conclusions about the factors that influence the evolution of traits.

Female ornaments, in contrast, are widely accepted to be shaped by social selection, with females competing for limited resources that are critical for fecundity [5,6,13]. This is because the reproductive success of females is generally more limited by access to resources than that of males, which is more limited by the access to females [14–17]. Females are therefore expected to compete for resources, whereas males are expected to compete for mates. However, this is a strong simplification as male reproductive success is restricted by resources in a wide range of species, particularly in species where males have to compete for resources critical for offspring survival, or defend the offspring against con- and heterospecifics. Moreover, males of many species reproduce repeatedly over their lifetime, and the minimization of investment into each reproductive cycle can increase the number of cycles completed and maximize reproductive success.

We investigated the relative use of a male ornament in sexual and social competition—the red nuptial coloration of the three-spined stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus—by examining its use in mate attraction and in the defence of a nest and offspring against rivals. Stickleback males develop a plastic red coloration while establishing a territory and building a nest, and express the colour while courting females [18]. Females leave after spawning, and males enter the parenting phase 2–3 days after receiving the first clutch of eggs [19]. After this, they no longer court females, but are highly aggressive against any individual that approaches the nest, both males and females. They spend most of their time hiding close to the nest, from where they attack intruders and fan fresh water into the nest. Neighbouring males and shoaling stickleback often attempt to destroy nests and cannibalize or steal eggs, and filial cannibalism occurs [20]. The parenting phase lasts for one to two weeks depending on water temperature.

Since the pioneering work of Tinbergen [21], the red nuptial coloration has been assumed to be sexually selected, and to function as a cue in female mate choice and as a status badge in male–male competition for access to females. However, males continue to express the colour during parenting when they no longer attract females [22,23]. This potentially suggests that the ornament serves a function in securing offspring survival. If the red coloration is primarily sexually selected, then males should invest most in the colour during the courtship stage, whereas if the colour is mainly socially selected, through competition for offspring survival and resources critical for offspring survival, then males should invest in the signal before the courtship stage, when defending the nest against rivals, and increase their investment in the signal during the parenting stage when the value of the nest has increased because of the addition of offspring. This is predicted by the theory of animal contests, which states that the investment into the defence of a resource depends on the value of the resource, and on the resource holding potential of the contestants (i.e. the ability of the contestants to acquire and retain resources) [24,25].

To determine the relative use of the red nuptial coloration in sexual and social competition, we allowed males to proceed to different stages of the breeding cycle (nesting, courting and parenting) in the absence or presence of male competition, and determined whether coloration at each stage correlated more strongly with mating success or with parenting success.

2. Material and methods

(a). Nest building

We collected three-spined stickleback with minnow traps from a shallow bay in the Baltic Sea (60° N, 23° E) before the breeding season started in May 2013. We allowed males with hints of nuptial coloration to build nests in individual 10 l flow-through tanks containing a nesting dish [26] in an outdoor facility with natural light, temperature and seawater conditions. We fed males defrosted chironomid larvae twice a day. To stimulate nest building, we presented a gravid female, enclosed in a perforated, transparent plastic box, to each male twice a day.

(b). Experimental treatments

To determine red coloration at the different stages—nesting, courting and parenting—we subjected randomly selected males with completed nests to one of four treatments in which they proceeded to different stages of the reproductive cycle during an 8-day period:

(1) Nesting: single males caring for a nest for 8 days.

(2) Nesting + courting: single males caring for a nest for 8 days and courting females on day 3.

(3) Nesting + courting + parenting: single males caring for a nest for 8 days, courting females on day 3, and caring for eggs from day 3 to day 8.

(4) Nesting + rival + courting + parenting: competing males caring for a nest for 8 days, courting females on day 3 and caring for eggs from day 3 to day 8.

The first treatment controlled for changes in coloration because of the passing of time; the second treatment revealed changes during courtship; the third treatment revealed changes during parenting; and the fourth treatment revealed the influence of the social environment on coloration at all stages.

For each treatment, we moved nesting males with their nesting dishes to experimental tanks (80 × 40 × 30 cm) divided into two compartments (40 × 40 cm) by an opaque Plexiglas divider. For the no-competition treatments (treatments 1–3), we placed one male into one of the two compartments and left the other empty. For the competition treatment (treatment 4), we placed one male into each compartment. The two males had completed nest building on the same day. On each side of the divider was a row of artificial vegetation [27]. Air stones at each short end kept the water circulating and oxygenated. We marked all males by clipping the tip of one of their dorsal spines.

We determined nuptial coloration for all males, at five time slots (or stages), independent of whether they experienced the next step in the reproductive cycle. This was done by photographing the left lateral side of the males following standardized procedures that do not influence male reproduction, as the stickleback is an unusually stress-tolerant species [28,29].

Stage 1 was the nesting stage. On day 2, after males had acclimatized to the experimental tanks for 1 day.

Stage 2 was the interaction stage. We removed the opaque Plexiglas divider after photographing the males at stage 1, but left the two rows of vegetation in place to serve as borders between the two compartments. This allowed males in the competition treatment to see each other and trespass into each other's territory. We photographed the males on day 3, after males in the competition treatment had interacted for 1 day.

Stage 3 was the courtship stage. We placed a transparent Plexiglas cylinder (diameter 12 cm) in the middle of the tank, 2 h after photographing the male(s) at stage 2. We placed a female into the cylinder in treatments 2–4, and allowed the male(s) to court the female for 15 min, after which we removed the female. After a 10 min break, we presented a second female to the male(s) for 15 min. We photographed the males immediately after removing the second female.

Stages 4 and 5 were the parenting stages. We placed the first female back into the tank for treatments 3 and 4, and allowed her to spawn with the male (or one of the males). We excluded replicates where sneak fertilization occurred, as this would influence the value of the offspring. Sneaking was detected by observing the males during spawning. We removed the female after spawning and placed the opaque divider back into the tank. For treatment 4 (competition), we allowed the other male to spawn with the second female. Lastly, we removed the opaque divider and allowed the males to care for the eggs. We photographed the males on day 3 and day 6 of parental care (stages 4 and 5). We placed the divider back into the tank during photographing to prevent competing males from reaching each other's nest, as one male at a time was photographed.

(c). Red coloration

From the digital images, we recorded the percentage of red area on the lateral side of the male, and the intensity of the colour, following standard procedures [9,28]. The similarity between human and stickleback vision allowed us to use the trichromatic colour system to analyse the colour [30]. Area and intensity of red coloration were positively correlated, and using either measure gave qualitatively similar results in the analyses. Results for red intensity are given in the electronic supplementary material.

(d). Female attraction and hatching success

We recorded the time elapsed until the female spawned with a male in treatments 3 and 4. In treatment 4 (competition), we also recorded female mate choice. To determine hatching success, we weighed the egg clutches 2 h after spawning, when the egg mass had hardened and a second time on day 6 of parental care, when we collected the egg clutches from the nests and ended the trial [27]. We removed any undeveloped eggs and dead embryos, and weighed the egg clutch to calculate the percentage of spawned eggs that had reached the hatching stage. Stolen eggs, which are easily separated from a male's own eggs by being buried just outside the nest and in poor condition, were not included in hatching success for either male.

All males experienced the same disturbance, as we removed and added the divider, the female cylinder and the nesting dish (when weighing eggs) at the same time slot in all tanks, independent of treatment. To analyse the effect of treatment and stage on red area, and the correlations between red area and courtship and parenting success, we used mixed-model ANOVAs with tank and male as random factors, with male nested within tank and red area as response variable. The factors inserted as independent variables are given for each test. Red area and hatching success were logit transformed, and time until spawning was log transformed.

3. Results and discussion

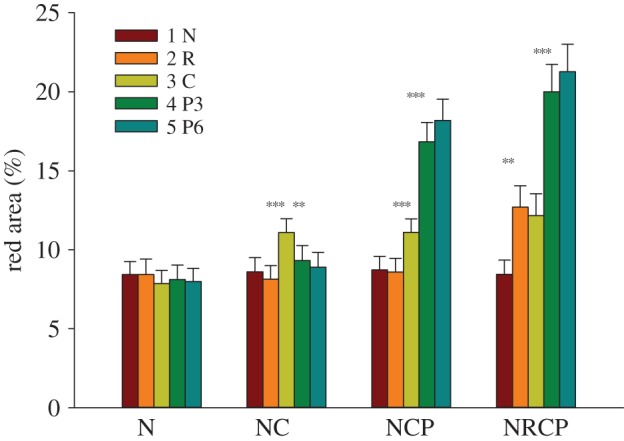

Males changed colour expression over time depending on treatment (LMM, treatment × stage: F12,488 = 14.97, p < 0.001): males increased coloration from nesting to courting to parenting, with the largest increase from courting to parenting (figure 1). Males also increased colour expression when confronted with a competitor before female presentations (figure 1). These results agree with the theory of contests [24,25]: males increased their investment into the ornament when confronted with a competitor for the nest site (the resource) and when the value of the defended resource increased because of the addition of fertilized eggs. Presenting gravid females to competing males did not further alter coloration (figure 1). Moreover, the increase in red coloration of solitary males when presented gravid females did not differ from that of competing males when presented a competitor (F1,104 = 0.61, n.s.). These results suggest that the colour was primarily used in social competition for nest sites and in the defence of developing embryos.

Figure 1.

Area of red on males that proceeded to different stages of the reproductive cycle: N, nesting; NC, nesting + courting; NCP, nesting + courting + parenting; NRCP, nesting + rival + courting + parenting. Red area was measured at five time slots (the five bars), which represented different stages of the reproductive cycle for males that proceeded to the stage: 1 N, nesting; 2 R, confronting a rival; 3 C, courting, 4 P3, parenting day 3; 5 P6, parenting day 6. LSD tests separately for each treatment: **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Results show mean ± s.e.m. for untransformed data. Dependencies within males are not shown.

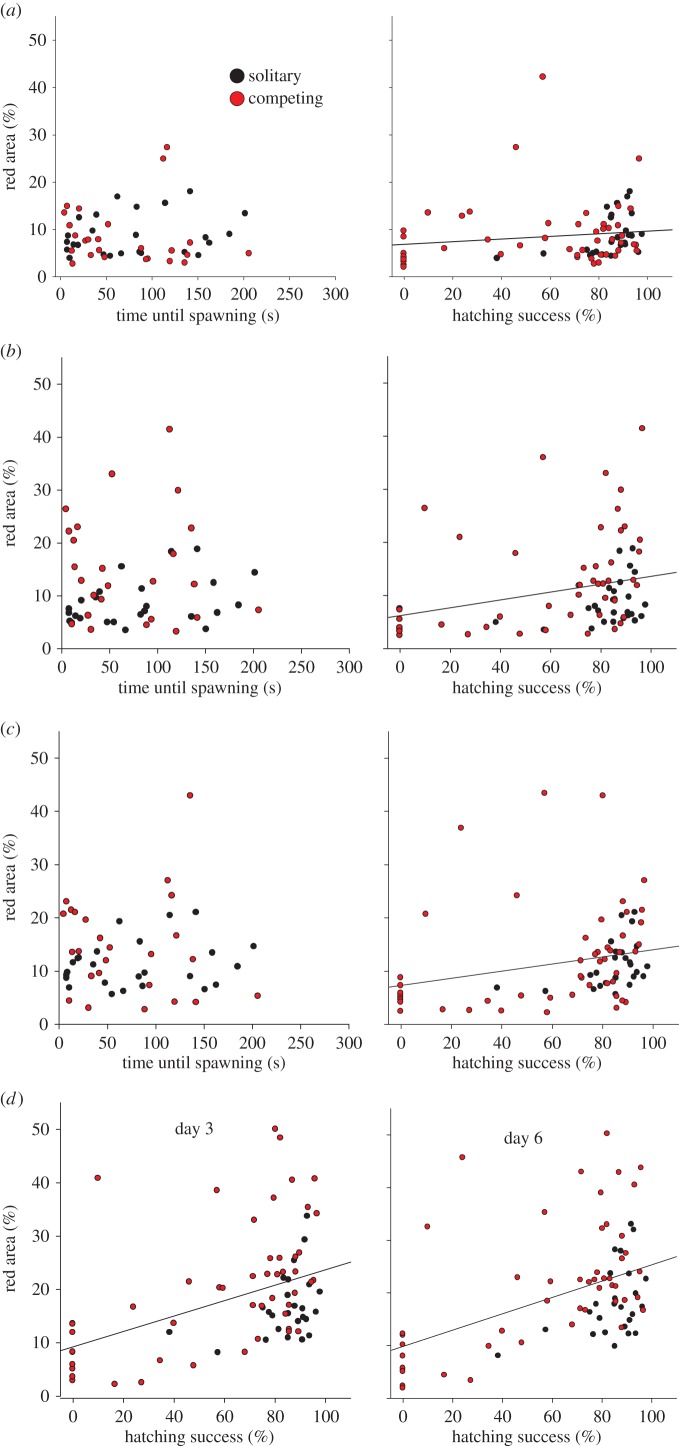

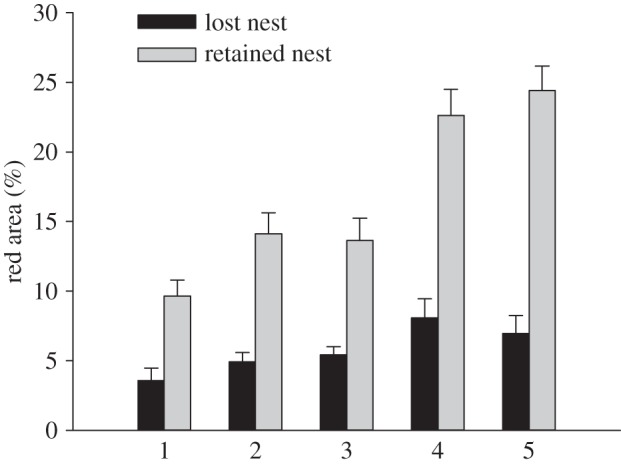

In support of the ornament primarily signalling male competitive ability during nest and offspring defence, coloration reflected parenting success but not attractiveness to females, in terms of female willingness to spawn with males (mixed model with treatment, stage, time until spawning and hatching success as independent variables: time until spawning, F1,46 = 0.16, n.s.; hatching success, F1,46 = 16.76, p < 0.001; only the values for the first male to spawn are included for competing males; figure 2). Moreover, coloration of competing males reflected nest retention during parenting: males that retained their nest during parenting were more colourful than males that lost their nest (F1,41 = 24.62, p < 0.001), and the difference was more marked for coloration at later stages (nest retention × stage: F4,192 = 2.65, p = 0.034; figure 3). This correlation cannot solely be caused by males fading in colour when losing their nest, as the correlation was apparent already at the nesting and the courtship stages, before males lost their nest. These results support the hypothesis that social selection has favoured the evolution of the colour as a social signal of the ability of the male to defend his nest and offspring.

Figure 2.

Area of red versus measures of reproductive success (i.e. time until spawning and hatching success). Black dots are solitary males (treatment 3), red dots are competing males (treatment 4). (a) Stage 1 when nesting. (b) Stage 2 after male interaction but before courtship. (c) Stage 3 after courtship. (d) Stage 4 on day 3 of parental care, and stage 5 on day 6 of parental care. Lines indicate simple linear regression (statistical test was done using a mixed models). Only the values for the first male to spawn are included for competing males. Untransformed vales are presented.

Figure 3.

Area of red at the five stages for competing males that lost their nest and those that retained their nest during parenting. Results show mean ± s.e.m. for untransformed data.

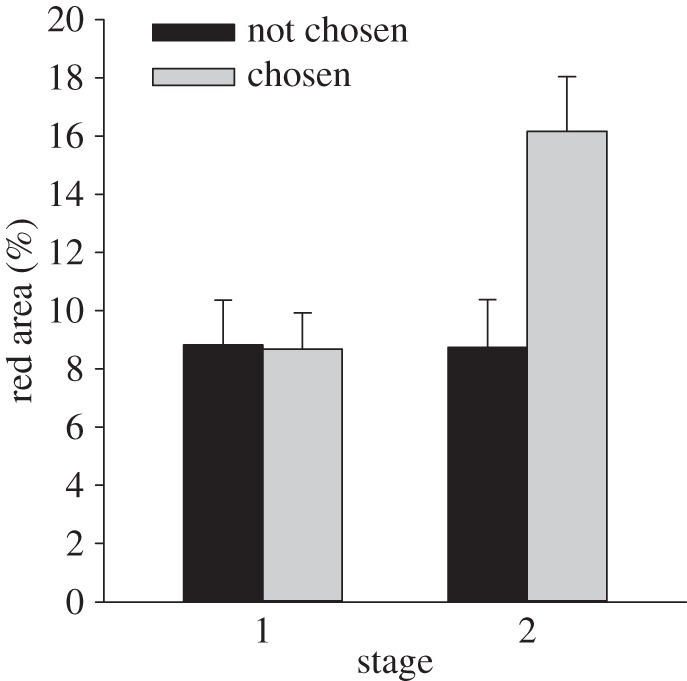

Regarding female mate choice, coloration did correlate with female mate choice after male–male interaction, but not before male–male interaction (mate choice × stage: F1,48 = 11.88, p = 0.001; figure 4). This indicates that the red coloration was not the primary cue used in female mate choice. Moreover, the correlation after male–male competition could be a consequence of male–male competition directly influencing female mate choice. For instance, the dominant, colourful male could have prevented the female from spawning with the subdominant male.

Figure 4.

Area of red at stage 1 before competition and at stage 2 after competition for the chosen and the not chosen male. Results show mean ± s.e.m. for untransformed data.

It is plausible that the change in coloration is not only due to increased benefits of signalling, but also to reduced costs, as signal expression is expected to be a balance between costs and benefits. The benefit of signalling defence ability increases from courting to parenting when the value of the defended resource increases, but at the same time the perceived predation risk cost could decrease, as parenting males hide next to their nest and leave it only when attacking intruders. However, reduced costs alone cannot explain the increase in red coloration during parenting, as benefits must be involved for males to continue to express the colour. Furthermore, the increase in coloration at the nesting stage when confronted with a competitor is unlikely to arise from reduced costs. Thus, changes in the benefit of the ornament are likely to have contributed to changes in expression. A further possibility is that the presence of eggs in the nest increased the investment of males into courtship during parenting, and hence into red coloration. However, this is highly unlikely as males stop courting 2–3 days after receiving a clutch of eggs (at the latest), after which they concentrate on nest defence and are extremely aggressive against both males and females [19].

These results challenge the current view that red coloration in the stickleback is primarily sexually selected through competition for mating success. Instead, the results suggest that the colour is mainly a social signal to conspecifics, and possibly to other species, of the breeding status of the male, and his ability and motivation to defend his nest and offspring against intruders. Signalling willingness and ability to fight could reduce costly fights, which in turn could favour the evolution of the signal through improved offspring survival and higher male residual reproductive value. Social selection rather than sexual selection would then be the main force promoting and maintaining the ornament in the population.

The colour could still serve a function in female mate choice, particularly when male–male competition sets colour expression to correlate with parenting success. However, the coloration is highly variable [18,27], and other behavioural, morphological and physiological cues are used by females, probably to gain a more complete picture of male phenotypic and genetic quality [31–33]. This could explain the variable results regarding the importance of the colour in female mate choice [29,34]. Whether the red coloration has originally evolved through sexual selection for mating success, or through social selection for offspring survival and future reproductive opportunities, or through a combination, remains to be determined. Moreover, the evolutionary pressures maintaining the coloration could have changed over time and vary among populations.

Our results raise the question of whether we have overlooked the operation of social selection beyond sexual selection in the evolution and maintenance of male ornaments also in other species. The stickleback is unusual in that the male alone cares for the offspring, but male care and the provisioning of resources critical for offspring survival are common in a range of species, across taxa [35]. Moreover, social selection is acknowledged to operate in both sexes during reproduction [4,5,12], although its role in the evolution of ornaments has mainly been investigated in females, whereas male ornaments are still typically assumed to arise through classic Darwinian sexual selection. We end by urging researchers to pay more attention to alternative explanations than sexual selection when investigating the evolution and maintenance of male ornaments. Misinterpreting the operation of selection forces could hamper our progress in unravelling the constraints and opportunities that govern evolutionary processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Joe Tobias and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments that significantly improved the paper, and Tvärminne Zoological Station for providing facilities.

Ethics

This study was approved by the regional ethics committee (permit number: STH421A National Animal Experiment Board in Finland), and was conducted according to national guidelines.

Data accessibility

The raw data are deposited in the Dryad database.

Authors' contributions

U.C. designed the research, I.T. and U.C. performed the experiment and analysed the data, and U.C. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

U.C. was supported by the Academy of Finland, the Kone Foundation and the Swedish Cultural Foundation in Finland, and I.T. by Walter and Andrée de Nottbeck Foundation.

References

- 1.Andersson M. 1994. Sexual selection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson M, Simmons LW. 2006. Sexual selection and mate choice. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 296–302. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2006.03.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobias JA, Seddon N. 2009. Signal design and perception in Hypocnemis antbirds: evidence for convergent evolution via social selection. Evolution 63, 3168–3189. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00795.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tobias JA, Gamarra-Toledo V, Garcia-Olaechea D, Pulgarin PC, Seddon N. 2011. Year-round resource defence and the evolution of male and female song in suboscine birds: social armaments are mutual ornaments. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 2118–2138. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02345.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West-Eberhard MJ. 1983. Sexual selection, social competition, and speciation. Q. Rev. Biol. 58, 155–183. ( 10.1086/413215) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tobias JA, Montgomerie R, Lyon BE. 2012. The evolution of female ornaments and weaponry: social selection, sexual selection and ecological competition. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 367, 2274–2293. ( 10.1098/rstb.2011.0280) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Searcy WA, Nowicki S. 2005. The evolution of animal communication. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berglund A, Bisazza A, Pilastro A. 1996. Armaments and ornaments: an evolutionary explanation of traits of dual utility. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 58, 385–399. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1996.tb01442.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maynard Smith J, Harper D. 2003. Animal signals. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoelzer GA. 1989. The good parent process of sexual selection. Anim. Behav. 38, 1067–1078. ( 10.1016/S0003-3472(89)80146-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly NB, Alonzo SH. 2009. Will male advertisement be a reliable indicator of paternal care, if offspring survival depends on male care? Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 3175–3183. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.0599) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clutton-Brock TH, Huchard E. 2013. Social competition and selection in males and females. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 20130074 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0074) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lebas NR. 2006. Female finery is not for males. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 170–173. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2006.01.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trivers RL, Campbell B. 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual selection and the descent of man 1871–1971 (ed. B Campbell), pp. 136–179. London, UK: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bateman AJ. 1948. Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity 2, 349–368. ( 10.1038/hdy.1948.21) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clutton-Brock T. 2007. Sexual selection in males and females. Science 318, 1882–1885. ( 10.1126/science.1133311) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clutton-Brock T. 2009. Sexual selection in females. Anim. Behav. 77, 3–11. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.08.026) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Candolin U. 2000. Changes in expression and honesty of sexual signalling over the reproductive lifetime of sticklebacks. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 267, 2425–2430. ( 10.1098/rspb.2000.1301) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraak SBM, Bakker TCM, Mundwiler B. 1999. Correlates of the duration of the egg collecting phase in the three-spined stickleback. J. Fish Biol. 54, 1038–1049. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb00856.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Candolin U, Vlieger L. 2013. Estimating the dynamics of sexual selection in changing environments. Evol. Biol. 40, 589–600. ( 10.1007/s11692-013-9234-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tinbergen N. 1951. The study of instinct. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKinnon JS. 1996. Red coloration and male parental behavior in the threespine stickleback. J. Fish Biol. 49, 1030–1033. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1996.tb00099.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLennan DA, McPhail JD. 1989. Experimental investigations of the evolutionary significance of sexually dimorphic nuptial coloration in Gasterosteus aculeatus (L): temporal changes in the structure of the male mosaic signal. Can. J. Zool. Rev. Can. Zool. 67, 1767–1777. ( 10.1139/z89-253) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maynard Smith J, Parker GA. 1976. The logic of asymmetric contests. Anim. Behav. 24, 159–175. ( 10.1016/s0003-3472(76)80110-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kokko H. 2013. Dyadic contests: modelling fights between two individuals. In Animal contests (eds Hardy ICW, Briffa M), pp. 5–32. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Candolin U. 1997. Predation risk affects courtship and attractiveness of competing threespine stickleback males. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 41, 81–87. ( 10.1007/s002650050367) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Candolin U. 2000. Increased signalling effort when survival prospects decrease: male–male competition ensures honesty. Anim. Behav. 60, 417–422. ( 10.1006/anbe.2000.1481) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Candolin U. 1999. The relationship between signal quality and physical condition: is sexual signalling honest in the three-spined stickleback? Anim. Behav. 58, 1261–1267. ( 10.1006/anbe.1999.1259) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heuschele J, Mannerla M, Gienapp P, Candolin U. 2009. Environment-dependent use of mate choice cues in sticklebacks. Behav. Ecol. 20, 1223–1227. ( 10.1093/beheco/arp123) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowe MP, Baube CL, Phillips JB. 2006. Trying to see red through stickleback photoreceptors: functional substitution of receptor sensitivities. Ethology 112, 218–229. ( 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01151.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milinski M, Griffiths S, Wegner KM, Reusch TBH, Haas-Assenbaum A, Boehm T. 2005. Mate choice decisions of stickleback females predictably modified by MHC peptide ligands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4414–4418. ( 10.1073/pnas.0408264102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mazzi D, Kunzler R, Bakker TCM. 2003. Female preference for symmetry in computer-animated three-spined sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 54, 156–161. ( 10.1007/s00265-003-0609-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Head ML, Kozak GM, Boughman JW. 2013. Female mate preferences for male body size and shape promote sexual isolation in threespine sticklebacks. Ecol. Evol. 3, 2183–2196. ( 10.1002/ece3.631) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braithwaite VA, Barber I. 2000. Limitations to colour-based sexual preferences in three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 47, 413–416. ( 10.1007/s002650050684) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Royle NJ, Smiseth PT, Kölliker M. 2012. The evolution of parental care. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data are deposited in the Dryad database.