The 3D structure of the eukaryotic genome and its spatial regulation within nuclei are governed by a range of architectural proteins. One class of such factors is the condensins, highly conserved multi-subunit protein complexes. Most eukaryotic species have 2 condensins, condensin I and II, and both condensins are essential for mitotic chromosome assembly and segregation, yet with distinct functions. However, increasing evidence indicates that condensins play diverse biological roles beyond mitosis and meiosis.1 Condensin II in particular has been implicated in the spatial organization of chromosomes during interphase, where condensin II facilitates chromosome territory formation.2 Yokoyama et al. now provide evidence for a new function of condensin II in the modulation of senescence and its associated alterations in chromatin structure (Fig. 1).3

Figure 1.

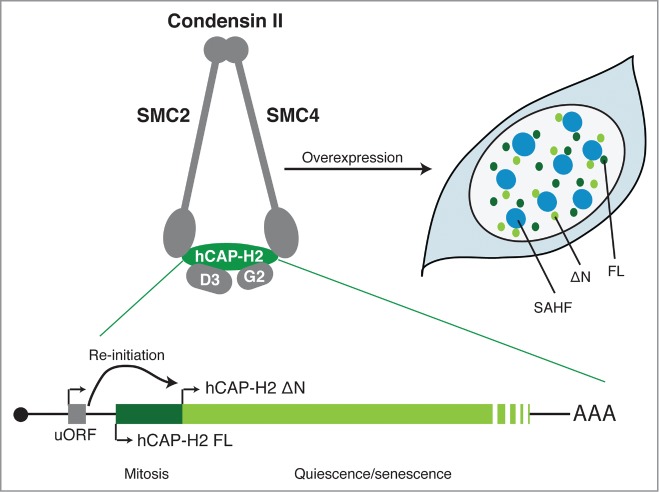

Two isoforms of hCAP-H2, the regulatory subunit of condensin II. The SMC2 and SMC4 subunits are members of the structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) family of chromosomal ATPases and are shared with condensin I. hCAP-D3 (D3) and hCAP-G2 (G2) are subunits unique to condensin II. uORF facilitates the re-initiation of translation from a downstream in-frame AUG (ΔN). The full-length (FL) isoform is mainly expressed at mitosis, whereas the ΔN appears to be expressed both in mitosis and interphase and is upregulated in both quiescence and senescence conditions. When overexpressed, both isoforms induce SAHF in IMR90 cells, where they are localized in the area surrounding SAHF. The mRNA diagram is not to scale.

Yokoyama et al. showed first that hCAP-H2, the regulatory subunit of condensin II, exists in at least 2 isoforms, a full-length (FL) and a shorter (ΔN) isoform, the latter lacking the first 50 amino acids. Although the relative expression of these 2 isoforms at the basal level appears to be cell type dependent, their expression levels and localization are differentially regulated during the cell cycle: the FL isoform is both expressed and associated with chromosomes primarily at mitosis, while the ΔN isoform, which is mostly localized at the nuclear matrix, accumulates in the quiescence and senescence states. Of note, some tumor cell lines only express hCAP-H2 FL, including HeLa cells, from which condensin II was originally identified.1

It has been shown that the activities of condensin are dynamically and tightly regulated at both the post-transcriptional and post-translational levels.1 For example, hCAP-H2 is a substrate of a number of mitotic kinases. Indeed, FL, but not ΔN, hCAP-H2 appears to be phosphorylated during mitosis.3 However, it is not entirely clear how condensin II is regulated during interphase. In Drosophila, condensin II activity is controlled through SCFSlimb E3 ubiquitin ligase-mediated degradation of Cap-H2, although a similar mechanism has not been found in mammalian cells.1 Yokoyama et al. provide additional mechanistic insight: they identified within the NCAPH2 transcript, a small upstream open reading frame (uORF), which facilitates a re-initiation of translation from the second in-frame AUG to produce the ΔN isoform, thus contributing to the reciprocal regulation of these isoforms at the post-transcriptional level. Perhaps these mechanisms collectively provide complexity in Cap-H2 regulation, allowing for the fine-tuned regulation of condensin II activities.

Yokoyama et al. went on to show that overexpression of either isoform is sufficient to induce senescence-associated heterochromatic foci (SAHFs) in human diploid cells, and, conversely, that endogenous hCAP-H2 is required for SAHF formation during oncogene-induced senescence (OIS). Notably, individual SAHFs are composed of single chromosomes, thus SAHF formation could be viewed as a process of chromosome territory modulation.4 This is consistent with the critical role for condensin II in organizing the genome into chromosome territories during interphase in part through its ability to induce the axial compaction of chromosomes and to suppress inter-chromosome interaction and the clusterization of peri-centric heterochromatin in Drosophila and mammalian cells.2,5

Another striking chromatin structure alteration during senescence is senescence-associated distension of satellites (SADS).6 Unlike SAHF, which has been best appreciated in OIS, SADS was suggested to occur more consistently in senescent cells regardless of the type of cell or trigger.6 Interestingly, ectopic expression of hCAP-H2 appears to induce senescence that exhibits SAHFs, but not SADS, highlighting the distinct nature of these 2 major senescence-associated chromatin alterations.

Interestingly it was recently shown that condensin II, together with other architectural proteins, is enriched at the borders of topologically associating domains (TADs), a chromatin unit in which frequent chromatin local-interactions were detected through a genome-wide chromosome conformation analysis (Hi-C).1 Another recent Hi-C study, using a SAHF-forming OIS model, revealed a global reduction in local chromatin interactions within TADs with increased longer interactions across TAD borders,7 supporting a model whereby SAHFs are formed through the spatial repositioning of the genome.4 Since TAD borders, where hCAP-H2 is enriched, are devoid of local chromatin interactions, it is tempting to speculate that the extra deposition of hCAP-H2 on chromatin facilitates SAHF formation through a global reorganization of local chromatin interactions. What remains to be elucidated includes: common and distinct functions between these isoforms at the endogenous level and how modulation of hCAP-H2 affects genomic structure and gene regulation as well as cell proliferation or tumorigenesis in the context of senescence. Although the ΔN isoform appears to be able to associate with other subunits of condensin II,3 it is unclear whether it functions in the condensin II complex and/or different forms of protein multimers. The link between condensin II and SAHF, a model for dynamic interphase chromatin re-organization, might provide an additional platform for condensin studies.

References

- 1.Lau AC, et al.. Front Genet 2014; 5:473; PMID:25628648; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fgene.2014.00473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer CR, et al.. PLoS Genet 2012; 8:e1002873; PMID:22956908; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yokoyama Y, et al.. Cell Cycle 2015; 14(13):2160-70; PMID:26017022; htto://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/15384101.2015.1049778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salama R, et al.. Genes Dev 2014; 28:99-114; PMID:24449267; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.235184.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishide K, et al.. PLoS Genet 2014; 10:e1004847; PMID:25474630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swanson EC, et al.. J Cell Biol 2013; 203:929-42; PMID:24344186; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201306073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandra T, et al.. Cell Rep 2015; 10:471-83; PMID:25640177; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]