Abstract

Activation of caspases is an integral part of the apoptotic cell death program. Collectively, these proteases target hundreds of substrates, leading to the hypothesis that apoptosis is “death by a thousand cuts”. Recent work, however, has demonstrated that caspase cleavage of only a subset of these substrates directs apoptosis in the cell. One such example is C. elegans CNT-1, which is cleaved by CED-3 to generate a truncated form, tCNT-1, that acquires a potent phosphoinositide-binding activity and translocates to the plasma membrane where it inactivates AKT survival signaling. We report here that ACAP2, a homolog of C. elegans CNT-1, has a pro-apoptotic function and an identical phosphoinositide-binding pattern to that of tCNT-1, despite not being an apparent target of caspase cleavage. We show that knockdown of ACAP2 blocks apoptosis in cancer cells in response to the chemotherapeutic antimetabolite 5-fluorouracil and that ACAP2 expression is down-regulated in some esophageal cancers, leukemias and lymphomas. These results suggest that ACAP2 is a functional homolog of C. elegans CNT-1 and its inactivation or downregulation in human cells may contribute to cancer development.

The caspases (cysteine aspartic acid proteases) are a class of proteases with diverse roles in cellular physiology including differentiation, inflammation and cell death.1–3 Caspases play a critical role in apoptosis, where they collectively target hundreds of proteins. One prevailing view is that caspases drive apoptosis through a mass action effect due to hundreds of proteolytic cleavage events that lead to cellular disassembly and cell death.4 Recent studies, however, suggest that proteolysis of most substrates may simply be a bystander effect and that caspase cleavage of key proteins controlling a few specific cellular processes is what functionally drives apoptosis.5 Although much of the work to date has focused on factors acting upstream of caspase activation, it is becoming increasingly clear that events downstream of this commitment step are also tightly regulated and critically important for apoptosis. Presently, there is evidence of requirements for caspase-mediated control of the BCL2 family of anti-apoptotic proteins, mitochondrial elimination, chromosome fragmentation, phosphatidylserine externalization, and, as we have recently reported, inactivation of the AKT survival signaling pathway in programmed cell death (Table 1).6-10 Therefore, a more thorough understanding of physiologically relevant caspase targets will increase our understanding of apoptosis in the context of animal development and disease.

Table 1.

Human homologues of functional caspase targets in C. elegans. A summary of identified caspase substrates and caspase downstream events important for cell death execution in C. elegans and humans

| Functional Caspase Targets | ||

|---|---|---|

| C. elegans | Human | Downstream Events |

| CED-9 | BCL2 | Inactivation of apoptosis inhibitors |

| DRP-1 | DRP1a | Mitochondrial elimination |

| DCR-1 | DFF40/45# | Chromosome fragmentation |

| CED-8 | XKR8 | PS externalization |

| CNT-1 | ACAP2 | Inactivation of AKT signaling |

Roles of DRP1 and FIS1 in apoptosis related mitochondrial elimination have not been extensively tested.

Proteins have similar functions but are not homologous

Caspase Control of Apoptosis

While hundreds of reported and predicted caspase substrates exist, depletion of many of them has little or no impact on apoptosis.11 Conversely, a substantial body of work has demonstrated that some caspase substrates actively drive apoptosis either by activating a cell-killing event or by inactivating a survival function. The BCL2 family (B-Cell Lymphoma-2) includes key components of the cell death machinery, and contains both pro- and anti-apoptotic members that perform integral roles in programmed cell death.12 Intriguingly, members of the BCL2 family act both upstream and downstream of caspase activation. BCL2 itself inhibits apoptosis through direct interactions with the pro-apoptotic family members BAX and BAK, which form pores in mitochondria to facilitate cytochrome C release.12 The C. elegans BCL2 homolog CED-9 was one of the first substrates discovered for the C. elegans caspase CED-3.6,13,14 Subsequent studies demonstrated that human BCL2 is also a caspase substrate and that its cleavage is required for efficient apoptosis.15 These early studies demonstrated an important regulatory role for caspase cleavage of a specific substrate, in this case, a potent survival factor (Table 1).

Studies elucidating mitochondrial functions in apoptosis have steadily expanded over the years. One new observation in mitochondrial apoptosis is that the dismantling of the mitochondrial network by the mitochondrial fission proteins DRP1 and FIS1 can promote apoptosis.16,17 Interestingly, CED-3 caspase cleavage of DRP-1 in C. elegans activates a pro-apoptotic DRP-1 fragment that acts with full length DRP-1 to promote mitochondrial elimination and apoptosis, indicating that DRP-1 can act downstream of the caspases to facilitate apoptotic progression.7

Chromosomal fragmentation is a hallmark of apoptosis that facilitates the cell death process. In mammals, this fragmentation is carried out by a number of nucleases, including the 40 kDa DNA Fragmentation Factor (DFF40).18 DFF40 is kept in check by its inhibitor, DFF45, a substrate of caspase-3.18-20 Although C. elegans has no predicted homologs of either of these proteins, DCR-1 (a homolog of human Dicer ribonuclease), is cleaved by CED-3, which converts it from an RNase to a DNase that directly initiates the chromosome fragmentation process.8 This represents a remarkable example of functional conservation via divergent mechanisms (Table 1).

Within organisms, apoptotic cell corpses are rapidly cleared by phagocytosis, thus preventing inflammatory processes triggered by release of intracellular contents. A major mechanism by which this is accomplished is the externalization of phosphatidylserine (PS) to the outer surface of the plasma membrane (PM), which serves as a marker for macrophage engulfment.21 While the exact mechanism of PS externalization remains poorly understood, two studies recently showed that the mammalian protein XKR8 (XK, Kell blood group complex subunit-related family, member 8) and its C. elegans homolog, CED-8, are important for PS exposure in apoptotic cells and that this activity requires a caspase cleavage event.9,22 Importantly, XKR8 is epigenetically silenced in a number of human cancer cell lines, including acute nonlymphocytic leukemia (ANLL) and Burkitt's lymphoma (BL), hinting that this protein may have a tumor suppressive function.

The PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway controls a wide range of cellular functions, ranging from cell proliferation, metabolism and cell survival, and represents a prime target for chemotherapeutic intervention due to the oncogenic potential of its components.23 We recently discovered a novel mechanism for inactivating AKT during apoptosis by means of a screen for suppressors of activated CED-3. We found that CNT-1 (Centaurin 1), a protein containing a Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain, is cleaved by CED-3, to generate a truncated CNT-1 (tCNT1), which has a potent phosphoinositide-binding activity. In turn, tCNT-1 translocates to the inner leaflet of the PM where it competes with AKT for binding to PIP3, thus suppressing AKT activity.10 While CNT-1 possesses no PIP3 binding ability, tCNT-1 binds to PIP3 through its PH domain with ∼100-fold greater affinity than AKT. This work uncovered a previous unknown link between cell death and cell survival signaling pathways. We now report a putative human homolog of CNT-1, ACAP2, which has a similar phosphoinositide binding pattern to that of tCNT-1 and a pro-apoptotic function in human cancer cells.

Human CNT-1 Homolog ACAP2 has a Pro-Apoptotic Role in Cancer Cells

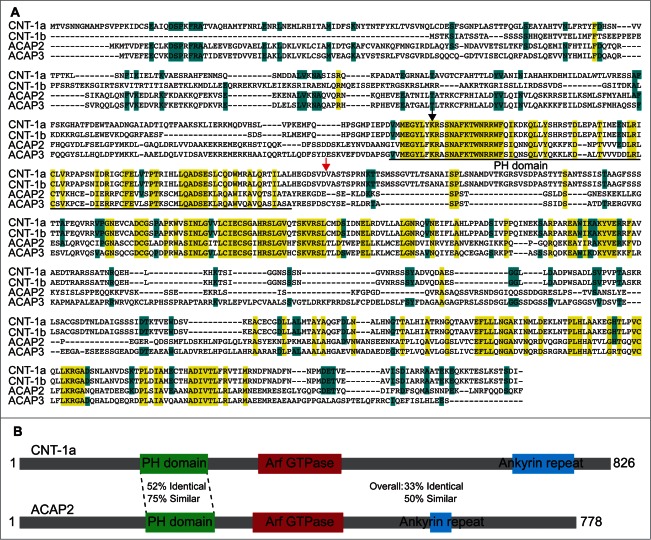

To investigate whether CNT-1 has human homologs, we performed a BLAST analysis that identified ACAP2 and ACAP3 (Fig. 1A). The ACAP (ArfGap with coiled-coil, ankyrin repeat and PH domains) family consists of 4 members in humans; ACAP1, ACAP2, ACAP3 and ASAP3. Relatively little is known about these ACAP proteins, though ACAP2 is a demonstrated RAB35 effector and a GTPase activating protein (GAP) for ARF6.24-26 We focused our studies on ACAP2 and ACAP3, as these proteins display the most significant homology with CNT-1 (33% identical, 50% similar and 35% identical, 53% similar, respectively), especially within their PH domains (52% identical, 75% similar and 52% identical, 76% similar, respectively, Fig. 1B), which is the critical domain for tCNT-1-mediated AKT inactivation.

Figure 1.

ACAP2 is a mammalian homolog of CNT-1. (A) Sequence alignment of 2 C. elegans CNT-1 isoforms (CNT-1a and CNT-1b) with human ACAP2 and ACAP3. Residues that are identical in all 4 proteins are shaded in yellow and residues that are identical in 3 of the 4 proteins are shaded in blue. The PH domain is underlined. The black arrowhead indicates the conserved lysine residue critical for lipid binding. The red arrow indicates the CED-3 cleavage site in CNT-1. (B) Schematic alignment of ACAP2 with CNT-1a with conservation information.

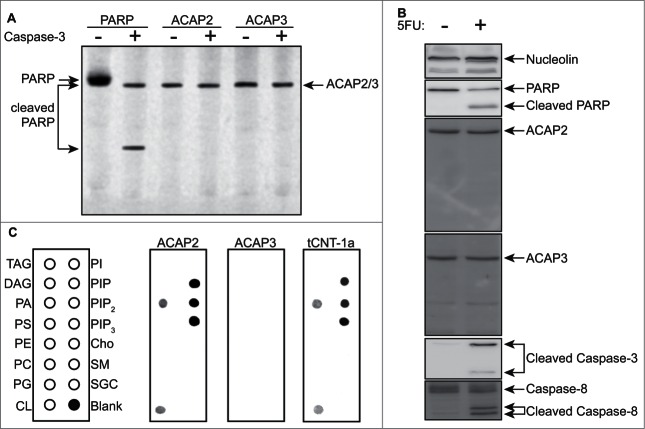

We first tested whether these proteins were caspase substrates. Interestingly, while both ACAP2 and ACAP3 are proteolytic cleavage targets in the Degrabase,27 neither appear to be caspase-3 substrates in vitro or cleaved in response to the chemotherapeutic antimetabolite 5-fluorouracil (5FU) in vivo in HCT116 colorectal cancer cells (Fig. 2, A and B). We next examined their phospholipid binding ability and found that, whereas ACAP3 does not have any detectable lipid binding, ACAP2 has an identical phosphoinositide-binding pattern to that of tCNT-1 (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

ACAP2 has an identical lipid-binding pattern to that of CNT-1. (A) Neither ACAP2 nor ACAP3 is cleaved by caspase-3 in vitro. PARP, ACAP2 and ACAP3 were synthesized and labeled with S35-Methionine(*) in rabbit reticulocyte lysate, incubated with or without 1 unit of purified caspase-3 for 2 hours, and then resolved by 15% SDS-PAGE. (B) ACAP2 and ACAP3 are not cleaved during apoptosis. HCT116 cells were treated with DMSO or 375 μM 5FU for 24 hours and cell lysates subjected to immunoblotting. ACAP2 and ACAP3 are not cleaved during apoptosis, whereas Caspase-3, Caspase-8, and PARP are. Nucleolin serves as a loading control. (C) ACAP2, but not ACAP3, displays a similar phosphoinositide binding activity to that of tCNT1a. ACAP2, ACAP3, and GST-tCNT-1a were synthesized and labeled with S35-MET(*) as in A and quantified as described in Materials and Methods. 40 nM of each protein was then added to the membrane strips.

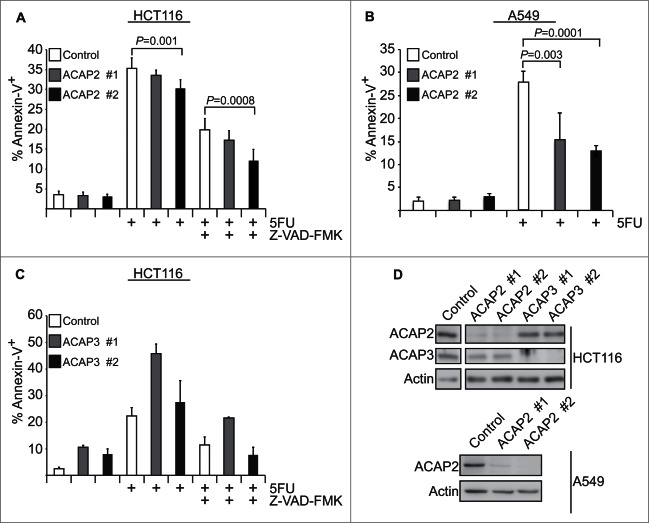

To determine whether these two CNT-1 homologs can promote apoptosis, we generated cell lines stably expressing short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeting ACAP2 or ACAP3 and tested if 5FU-induced apoptosis is compromised in these cell lines. Knockdown of ACAP2 with two independent shRNAs reduces 5FU-induced apoptosis in HCT116 colorectal carcinoma cells and this effect is exacerbated by a partial blockage of apoptosis with the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (Fig. 3A), similar to the enhanced apoptosis inhibition observed in the cnt-1(tm2313); ced-3(n2438) double mutant worm, in which the CED-3 caspase is partially compromised.10 ACAP2 knockdown similarly reduces apoptosis in response to 5FU in A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells (Fig. 3B), which are slightly more resistant to 5FU-induced killing than HCT116 cells. In both HCT116 and A549 cells, ACAP2 shRNA#2, which reproducibly has a greater effect in reducing the level of ACAP2 expression than ACAP2 shRNA #1, shows a stronger apoptosis inhibitory effect (Fig. 3A, B, D). Conversely, neither of the two shRNAs targeting ACAP3 reduced apoptosis in HCT116 cells. Instead, loss of ACAP3 appears to increase levels of apoptosis, even in untreated cells, indicating a potential pro-survival role for this protein (Fig. 3C). Together, these data demonstrate that while ACAP2 does not appear to be a cleavage target of caspases in our system, it does bind to PIP3 and has a pro-apoptotic role in cancer cells. This raises the interesting question of how ACAP2 pro-apoptotic activity is controlled in living cells.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of human ACAP2 reduces 5FU-induced apoptosis in cancer cells. (A, C) HCT116 cells stably expressing shRNAs targeting ACAP2, ACAP3, or a non-targeting control (Ctrl) were treated with 375 μM 5FU for 24 hours prior to analysis of phosphatidylserine externalization (Annexin V) via flow cytometry. Where indicated, cells were pretreated with 2 μM Z-VAD-FMK for 1 hour. (B) A549 cells stably expressing shRNAs targeting ACAP2 or a non-targeting control (Ctrl) were treated and analyzed as in A. All Data shown represent at least 3 independent experiments +/− SEM. P-values were calculated using Student's t-test (unpaired, 2-tailed). (D) Immunoblots showing degree of ACAP2 and ACAP3 knockdown for 2 independent shRNAs.

ACAP2 is Downregulated in Specific Cancer Types

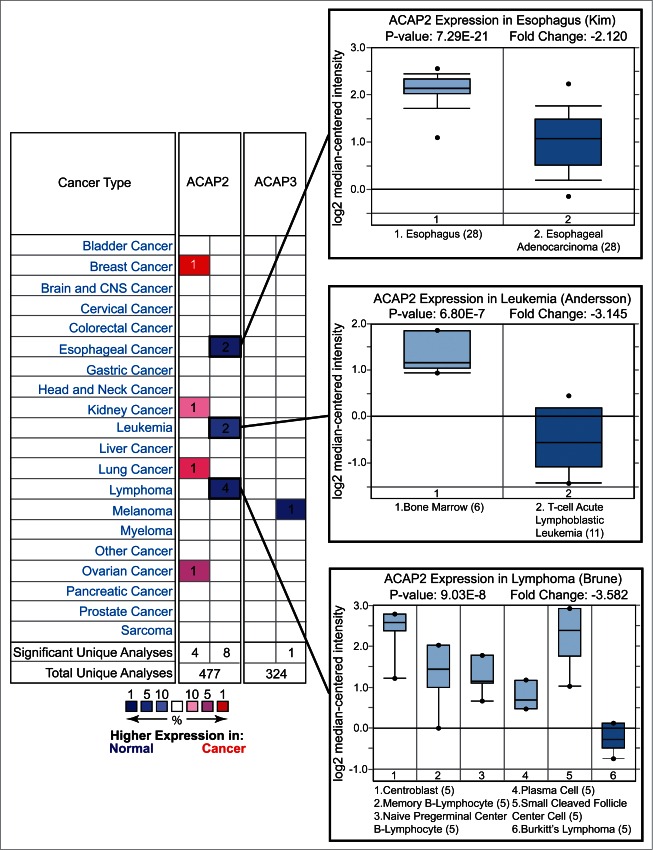

We next surveyed the Oncomine database and found that ACAP2, but not ACAP3, is downregulated in a number of cancers including esophageal cancer, and similarly to XKR8, in leukemia and lymphoma (Fig. 4).22 Furthermore, analysis of the COSMIC (catalog of somatic mutations in cancer, http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/cosmic/) database revealed that while both ACAP2 and ACAP3 are the targets of somatic mutations, only ACAP2 has multiple identical mutations within the PH domain (Table 2).28 Additionally, SIFT (Sorting Tolerant From Intolerant) predicts that all reported G707 mutations are deleterious, as are the A114 mutations in ACAP3 (Table 2). These data highlight ACAP2 as a potential tumor suppressor, however, further studies are required to solidify the role of ACAP2 mutations in cancer progression.29 Taken together, these results indicate that ACAP2 plays a pro-apoptotic role in human cells and its inactivation or downregulation may contribute to cancer development. Supporting this notion, one recent study implicated somatic ACAP2 mutations in Imatinib-resistant dermatofibrosarcoma.30

Figure 4.

For figure caption, see page 1776.Figure 4 (See previous page) Oncomine analysis of ACAP2 and ACAP3 expression levels in cancer versus normal cells. (Left) A summary of comparisons of ACAP2 and ACAP3 expression levels in different cancer vs. normal tissue datasets. The bottom rows in each case indicate the total number of unique analyses and the number of unique analyses that show significant overexpression (red) or underexpression (blue) of the target gene in the cancer samples relative to the normal tissue samples. Color intensity indicates the percentile rank of genes (key at bottom) displaying significant overexpression or underexpression. (Right) Box and whisker plots of representative studies profiling decreased expression of ACAP2 in esophageal cancer, leukemia and lymphoma. Details include study name, P-value, t-test score and fold change. Tissue or cancer type is indicated below the plots with the number of analyzed samples indicated in parentheses.

Table 2.

Mutations in ACAP2 and ACAP3 in COSMIC database. Summary of non-synonymous mutations in ACAP2 and ACAP3 with multiple reports in COSMIC. Columns include mutation in coding sequence, AA (amino acid) Mutation, COSMIC Mutation ID, number of reports in COSMIC and mutation type

| ACAP2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDS Mutation | AA Mutation | Mutation ID | Count | Type |

| c.1046G > A | p.R349H | 209355 | 2 | Substitution-Missense |

| c.1532A > G | p.K511R | 1421812 | 1 | Substitution-Missense |

| c.1532A > T | p.K511I | 50517 | 1 | Substitution-Missense |

| c.2119G > T | p.G707W | 318470 | 1 | Substitution-Missense |

| c.2119_2120GG > TC | p.G707 > ? | 308804 | 1 | Complex |

| c.2120G > C |

p.G707A |

318469 |

1 |

Substitution-Missense |

| ACAP3 | ||||

| CDS Mutation | ||||

| c.340G > T | p.A114S | 4021389 | 1 | Substitution-Missense |

| c.341C > T | p.A114V | 3472433 | 1 | Substitution-Missense |

Although ACAP2 does not appear to be a direct caspase target, it shares two important characteristics with tCNT-1. First, it has an identical lipid-binding pattern to that of tCNT-1, including PIP3 binding. Second, it has a pro-apoptotic role in the cell. Perhaps, like DCR-1 and DFF40/DFF45 in chromosome fragmentation, ACAP2 and tCNT-1 play similar roles in disabling AKT signaling through competing for PIP3 binding, but are activated through different mechanisms. Further studies of ACAP2 action and regulation in the cell will be important for understanding the contribution of the ACAP family to apoptosis.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Caspase activation is considered to be the point of no return for cell death and a crucial checkpoint for uncontrolled cell proliferation and cancer prevention. As such, much attention has been focused on studying upstream regulators of caspases and therapeutic manipulation of these regulators. However, increasing evidence suggests that effectors acting downstream of caspases are also important for apoptosis execution, and similarly could play important roles in suppressing uncontrolled cell proliferation. It will be interesting to determine whether the collective action of multiple caspase downstream effectors is sufficient to activate apoptosis. Identification of additional downstream effectors will continue to unravel novel modes of regulation in the apoptotic cascade post caspase activation. One intriguing question which has arisen from the newly defined roles of these caspase downstream effectors is whether or not they are additive in their contributions to the apoptotic process. Further study into the roles of human FIS1, DRP1 and ACAP2 is also required to determine whether FIS1 and DRP1 are involved in apoptotic mitochondrial fragmentation and to determine the mechanism of activation of ACAP2.

Materials and Methods

Lipid binding assays

tCNT-1a, ACAP2 and ACAP3 were synthesized and labeled with 35S-Methionine using the TNT system as described previously.10 Membrane strips containing various lipids (Echelon Biosciences) were blocked in 3% fatty-acid free bovine serum albumin (Sigma) in PBST (PBS + 0.01% Tween 20) for 1 hour and washed 3 times with PBST. The membrane strips were then incubated with the labeled proteins in PBST at 1/1,000 dilution for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing 3 times with PBST, the membrane strips were subjected to autoradiography.

Cell culture, lentiviral work, and drug treatments

Cell culture, lentiviral work and drug treatments were performed as described.31 HCT116 cells were cultured in McCoy's 5A Medium and A549 cells in DMEM/F12 (Media from Gibco). Media were supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (SAFC Biosciences) and antibiotic/antimycotic mix (Gibco Cat. No. 15240). shRNA cell lines were generated via linear polyethelenimine transfection of HEK293FT cells with pLKO vectors (University of Colorado-Functional Genomics Facility) for 48 hours, followed by a 24-hour transduction of target cells with polybrene. Transduced cells were selected with 10 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma). 5FU (Sigma) and Z-VAD-FMK (Tocris) were solubilized in DMSO and used to treat cells at the indicated concentrations for the indicated times.

shRNA sequences: Non-Targeting: 5′ CCGGCAACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAAC-TCGAGTTGGTGCTCTTCATCTTGTTGTTTTT 3′

ACAP2 #1: 5′ CCGGCCTAGCTTTCATACACATAATCTCGAGATTATGTGTA-TGAAAGCTAGGTTTTTG 3′

ACAP2 #2: 5′ CCGGCCAGTATTGCTACTGCTTATACTCGAGTATAAGCAGT-AGCAATACTGGTTTTTG 3′

ACAP3 #1: 5′ CCGGCCAGCAACGCTTTCAAGACATCTCGAG-ATGTCTTGAA-AGCGTTGCTGGTTTTTTG 3′

ACAP3 #2: 5′ CCGGCGATGAGTCCAAAGTGGAGTTCTCGAGAACTCCACTT-TGGACTCATCGTTTTTTG

Flow cytometry and immunoblotting

Cells were harvested by trypsinization and washed once in PBS. 1 × 105 cells were resuspended in 100 μL Annexin V binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) with 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC (Life Technologies Cat. No. A13199) for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. An additional 400 μL of Annexin V Binding Buffer were added to each sample and they were analyzed on an Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer. Antibodies used for western blots are as follows: Caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. No. 9661), Caspase-8 (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. No. 9746), Actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat. No. sc-1616), Nucleolin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat. No. sc-8031), ACAP2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat. No. sc-48959), ACAP3 (Abcam, Cat. No. ab100851), and PARP (Enzo Life Sciences, Cat. No. BML-SA250).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1CA117907 to JME and R01GM059083 and R01GM079097 to DX) and a New Idea Award from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. JME is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Early Career Scientist. We also thank the University of Colorado Functional Genomics Facility, which is supported by a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA046934), for support.

References

- 1.Shalini S, Dorstyn L, Dawar S, Kumar S. Old, new and emerging functions of caspases. Cell Death Differ [Internet] 2014. [cited 2014December21]; Available from: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2014.216; PMID:25526085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford ED, Wells JA. Caspase substrates and cellular remodeling. Annu Rev Biochem [Internet] 2011. [cited 2014October29]; 80:1055-87. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-121639; PMID:21456965; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061809-121639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poreba M, Strózyk A, Salvesen GS, Drag M. Caspase substrates and inhibitors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol [Internet] 2013. [cited 2014November28]; 5:a008680. Available from: http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/content/5/8/a008680.long; PMID:23788633; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a008680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stroh C, Schulze-Osthoff K. Death by a thousand cuts: an ever increasing list of caspase substrates. Cell Death Differ [Internet] 1998. [cited 2015January9]; 5:997-1000. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9894605; PMID:9894605; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crawford ED, Seaman JE, Barber AE, David DC, Babbitt PC, Burlingame AL, Wells JA. Conservation of caspase substrates across metazoans suggests hierarchical importance of signaling pathways over specific targets and cleavage site motifs in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ [Internet] 2012. [cited 2015January9]; 19:2040-8. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3504717&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract; PMID:22918439; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2012.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xue D, Horvitz HR. Caenorhabditis elegans CED-9 protein is a bifunctional cell-death inhibitor. Nature [Internet] 1997. [cited 2014December30]; 390:305-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9384385; PMID:9384385; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/36889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breckenridge DG, Kang B-H, Kokel D, Mitani S, Staehelin LA, Xue D. Caenorhabditis elegans drp-1 and fis-2 regulate distinct cell-death execution pathways downstream of ced-3 and independent of ced-9. Mol Cell [Internet] 2008. [cited 2014December30]; 31:586-97. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2548325&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract; PMID:18722182; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakagawa A, Shi Y, Kage-Nakadai E, Mitani S, Xue D. Caspase-dependent conversion of Dicer ribonuclease into a death-promoting deoxyribonuclease. Science [Internet] 2010. [cited 2014December7]; 328:327-34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20223951; PMID:20223951; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1182374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y-Z, Mapes J, Lee E-S, Skeen-Gaar RR, Xue D. Caspase-mediated activation of Caenorhabditis elegans CED-8 promotes apoptosis and phosphatidylserine externalization. Nat Commun [Internet] 2013. [cited 2014December15]; 4:2726. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3939056&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract; PMID:24225442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakagawa A, Sullivan KD, Xue D. Caspase-activated phosphoinositide binding by CNT-1 promotes apoptosis by inhibiting the AKT pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol [Internet] 2014. [cited 2014December30]; 21:1082-90. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25383666; PMID:25383666; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Timmer JC, Salvesen GS. Caspase substrates. Cell Death Differ [Internet] 2007. [cited 2015January7]; 14:66-72. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17082814; PMID:17082814; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol [Internet] 2008. [cited 2014July9]; 9:47-59. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2308; PMID:18097445; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue D, Shaham S, Horvitz HR. The Caenorhabditis elegans cell-death protein CED-3 is a cysteine protease with substrate specificities similar to those of the human CPP32 protease. Genes Dev [Internet] 1996. [cited 2015January5]; 10:1073-83. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8654923; PMID:8654923; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.10.9.1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue D, Horvitz HR. Inhibition of the Caenorhabditis elegans cell-death protease CED-3 by a CED-3 cleavage site in baculovirus p35 protein. Nature [Internet] 1995. [cited 2015January5]; 377:248-51. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7675111; PMID:7675111; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/377248a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirsch DG, Doseff A, Chau BN, Lim D-S, de Souza-Pinto NC, Hansford R, Kastan MB, Lazebnik YA, Hardwick JM. Caspase-3-dependent Cleavage of Bcl-2 Promotes Release of Cytochrome c. J Biol Chem [Internet] 1999. [cited 2014December30]; 274:21155-61. Available from: http://www.jbc.org/content/274/30/21155.full; PMID:10409669; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.274.30.21155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank S, Gaume B, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Leitner WW, Robert EG, Catez F, Smith CL, Youle RJ. The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev Cell [Internet] 2001. [cited 2015January6]; 1:515-25. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11703942; PMID:11703942; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00055-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James DI, Parone PA, Mattenberger Y, Martinou J-C. hFis1, a novel component of the mammalian mitochondrial fission machinery. J Biol Chem [Internet] 2003. [cited 2014December3]; 278:36373-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12783892; PMID:12783892; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M303758200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Zou H, Slaughter C, Wang X. DFF, a heterodimeric protein that functions downstream of caspase-3 to trigger DNA fragmentation during apoptosis. Cell [Internet] 1997. [cited 2015January6]; 89:175-84. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9108473; PMID:9108473; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80197-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakahira H, Enari M, Nagata S. Cleavage of CAD inhibitor in CAD activation and DNA degradation during apoptosis. Nature [Internet] 1998. [cited 2015January6]; 391:96-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9422513; PMID:9422513; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/34214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enari M, Sakahira H, Yokoyama H, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. A caspase-activated DNase that degrades DNA during apoptosis, and its inhibitor ICAD. Nature [Internet] 1998. [cited 2014December12]; 391:43-50. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9422506; PMID:9422506; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/34112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fadok VA, Voelker DR, Campbell PA, Cohen JJ, Bratton DL, Henson PM. Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes triggers specific recognition and removal by macrophages. J Immunol [Internet] 1992. [cited 2014December1]; 148:2207-16. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1545126; PMID:1545126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki J, Denning DP, Imanishi E, Horvitz HR, Nagata S. Xk-related protein 8 and CED-8 promote phosphatidylserine exposure in apoptotic cells. Science [Internet] 2013. [cited 2014November2]; 341:403-6. Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/341/6144/403.long; PMID:23845944; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1236758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fruman DA, Rommel C. PI3K and cancer: lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov [Internet] 2014. [cited 2014July9]; 13:140-56. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrd4204; PMID:24481312; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrd4204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson TR, Brown FD, Nie Z, Miura K, Foroni L, Sun J, Hsu VW, Donaldson JG, Randazzo PA. ACAPs are arf6 GTPase-activating proteins that function in the cell periphery. J Cell Biol [Internet] 2000. [cited 2015January6]; 151:627-38. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2185579&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract; PMID:11062263; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.151.3.627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyamoto Y, Yamamori N, Torii T, Tanoue A, Yamauchi J. Rab35, acting through ACAP2 switching off Arf6, negatively regulates oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Mol Biol Cell [Internet] 2014. [cited 2015January6]; 25:1532-42. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4004601&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract; PMID:24600047; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E13-10-0600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi H, Fukuda M. Rab35 regulates Arf6 activity through centaurin-β2 (ACAP2) during neurite outgrowth. J Cell Sci [Internet] 2012. [cited 2015January6]; 125:2235-43. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22344257; PMID:22344257; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.098657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crawford ED, Seaman JE, Agard N, Hsu GW, Julien O, Mahrus S, Nguyen H, Shimbo K, Yoshihara HAI, Zhuang M, et al.. The DegraBase: a database of proteolysis in healthy and apoptotic human cells. Mol Cell Proteomics [Internet] 2013. [cited 2015January6]; 12:813-24. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3591672&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract; PMID:23264352; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/mcp.O112.024372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forbes SA, Tang G, Bindal N, Bamford S, Dawson E, Cole C, Kok CY, Jia M, Ewing R, Menzies A, et al.. COSMIC (the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer): a resource to investigate acquired mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res [Internet] 2010. [cited 2014November20]; 38:D652-7. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2808858&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract; PMID:19906727; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkp995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc [Internet] 2009. [cited 2014July14]; 4:1073-81. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19561590; PMID:19561590; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nprot.2009.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong JY, Liu X, Mao M, Li M, Choi DI, Kang SW, Lee J, La Choi Y. Genetic aberrations in imatinib-resistant dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans revealed by whole genome sequencing. PLoS One [Internet] 2013. [cited 2015January6]; 8:e69752. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3726773&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract; PMID:23922791; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0069752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullivan KD, Padilla-Just N, Henry RE, Porter CC, Kim J, Tentler JJ, Eckhardt SG, Tan AC, DeGregori J, Espinosa JM. ATM and MET kinases are synthetic lethal with nongenotoxic activation of p53. Nat Chem Biol [Internet] 2012. [cited 2014May1]; 8:646-54. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3430605&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract; PMID:22660439; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nchembio.965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]