Abstract

Group II introns are self-splicing catalytic RNAs found in bacteria and the organelles of fungi and plants. They are thought to share a common ancestor with the spliceosome, which catalyzes the removal of nuclear introns from pre-mRNAs in eukaryotes. Recent structural and biochemical evidence supports the hypothesis that the spliceosome has a catalytic RNA core homologous to that found in group II introns. The crystal structure of a eukaryotic group IIB intron was recently determined and reveals the architecture of a branched lariat RNA that is also formed by the spliceosome. Here we describe the active site components of this intron and propose a model for RNA splicing involving dynamic base triples in the catalytic triad. Based on this structure, we draw analogies to the U2/U6 snRNA pairing and RNA-protein interactions that form in the active site of the spliceosome.

Keywords: branch point, group II intron, lariat, RNA splicing, spliceosome

Introduction

Group II introns are self-splicing ribozymes found in all 3 domains of life. They are predominantly found in bacteria as well as in the mitochondria and chloroplasts of some eukaryotes, and rarely in archaea.1 The secondary structure of group II introns can be subdivided into 6 domains that fold into an ordered three-dimensional structure that catalyzes splicing via 2 transesterification reactions. In the first step, the 2′-hydroxyl of a bulged adenosine in domain VI attacks the 5′ splice site resulting in the formation of a branched RNA containing a 2′-5′ phosphodiester bond (known as the ‘lariat’) and a free 3′-hydroxyl of the newly cleaved 5′ exon.2,3 In the second step, this 3′-hydroxyl attacks the 3′ splice site resulting in ligated exons and the release of intron lariat. The stereochemistry of this reaction is identical to that seen in the spliceosome, which removes nuclear introns from pre-mRNAs. The group II intron and spliceosome are postulated to share a common ancestor based on similarities in conserved core RNA structures and mechanism. Recent biochemical evidence has also shown that the spliceosome is a ribozyme that uses a two-metal-ion mechanism of catalysis.4 Two spliceosomal RNAs, U2 and U6, comprise the active site and are capable of performing a splicing-related reaction in the absence of spliceosomal proteins.5,6

Of the 3 structural classes of group II introns (IIA, IIB, and IIC), IIC introns are thought to be the most primitive.7 IIA and IIB introns typically form large amounts of lariat RNA during in vitro self-splicing reactions, whereas IIC introns primarily splice through hydrolysis in vitro to form linear intron.8 Previously, a crystal structure of a hydrolytic IIC intron from the bacterium Oceanobacillus iheyensis (O. iheyensis) revealed that the highly conserved DV forms an active site containing 2 catalytic magnesium ions.9 However, this structure lacked domain VI (DVI), which contains the bulged adenosine nucleophile required for lariat formation in the first step. The recent crystal structure of a post-catalytic, eukaryotic group IIB intron from the brown algae Pylaiella littoralis (P.li.LSUI2) contains a functional DVI.10 Given that this intron catalyzes lariat formation,11 it has contributed to a new understanding of the structural requirements for splicing in higher eukaryotes.

Newly Visualized DVI

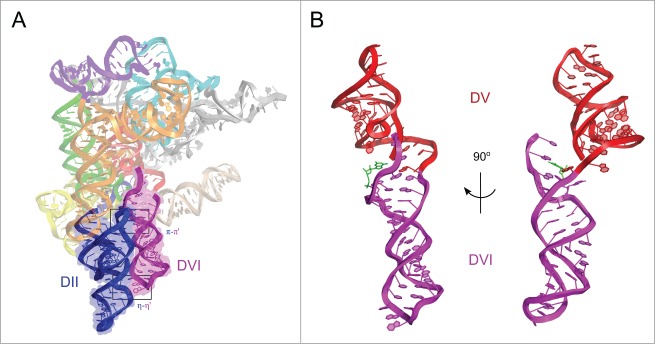

DVI contains the bulged adenosine residue analogous to the branch site adenosine found in spliceosomal introns. Given its importance in lariat formation, the location and orientation of DVI within the group II intron has been a long-standing question in the field of RNA splicing. There have been several proposed models for DVI, with some postulating a side-by-side packing with the catalytic DV, and others placing DVI at ∼90° from DV in the first step.12,13 The structure of the intron lariat finally allowed visualization of DVI and the tertiary interactions that position it in the catalytic core. In this structure, the 2 distal stems of domain II (DII), D2a and D2b, coaxially stack and form 2 tetraloop-receptor interactions with DVI (Fig. 1A). The GAGA tetraloop in DVI docks into the receptor at the base of D2a (η-η′), and the GCAA tetraloop in D2b docks into a receptor directly adjacent to the bulged adenosine in DVI (π-π′). These two tetraloop-receptor interactions position DVI in the core of the intron at a ∼180° angle from DV in a conformation in which these 2 helices are not coaxially stacked on each other (Fig. 1B). Mutagenesis of either of these GNRA tetraloops to a non-interacting UUCG results in an accumulation of intermediate splicing products consisting of lariat-3′ exon and 5′ exon. Furthermore, a construct containing both mutated tetraloops results in an almost complete block of the second step.10 The discovery of the π-π′ interaction is interesting due to its proximity to the bulged adenosine residue A615. This interaction provides the means for removal of the lariat bond from the active site after the first step to allow entry of the 3′ splice site for the second step.

Figure 1.

Overall tertiary structure of P.li.LSUI2. (A) Interactions between DII and DVI. The two distal stems of DII (blue) coaxially stack and align parallel to DVI (purple). The two tetraloop-receptor interactions between domains II and VI, η-η′ and π-π′, are indicated with black boxes. Individual domains and subdomains are shown in different colors. (B) Arrangement of DV and DVI. DV (red) and DVI (purple) are oriented 180° relative to each other. The image on the left shows the 2 domains from the same angle as (A). The image on the right is rotated 90° about the y-axis to show that the 2 domains are not coaxially stacked. G1 is shown in green and interacts with A620.

Previous models proposed a large-scale “swinging-arm” movement of the distal end of DVI (containing the tetraloop) with η-η′ being disengaged for the first step of splicing.12,13 However, the pre-catalytic state of P.li.LSUI2 at 7 Å revealed strong electron density for the η-η′ interaction,10 demonstrating that this contact persists through both steps of splicing and suggesting that large scale movement of DVI is unlikely. Therefore, we propose a more subtle conformational change in which DVI remains 180° from DV with π-π′ being disengaged for the first step of splicing and engaged for the second step. This allows the bulged adenosine to reach the active site in the first step. Upon lariat formation, π-π′ engages, removing the bulged adenosine from the active site while simultaneously pulling the attached 3′ splice site into the core.

An analogous interaction sequestering the adenosine nucleophile after the first step likely exists in the spliceosome. A possible spliceosomal counterpart could be an RNA-RNA interaction between the U5 snRNA and a region just downstream of the branch site.14 However, this may also be accomplished via an RNA-protein interaction. Another possibility for a π-π′ analog is the spliceosomal p14 protein, which crosslinks directly to the branch site adenosine.15 It has been proposed that this RNA-protein interaction must be disrupted to allow for the first step of splicing,16,17 in a manner similar to π-π′. The conserved protein Prp8 could be yet another candidate for engaging in an equivalent π-π′ interaction since it has been also shown to crosslink to the branch site as well as other key regions in the spliceosomal core, such as the 5′ and 3′ exons.18-20 Mutations in RNA binding regions of Prp8 result in both first and second step defects, indicating an essential role in positioning substrates in the active site.21 There is also structural evidence suggesting that Prp8 is derived from a group II intron encoded protein (IEP), also known as a maturase.22 Maturases assist in the proper folding of group II introns in vivo.1 In a similar manner, Prp8 likely functions as an assembly platform in the spliceosome to mediate intron removal by snRNAs.

Active Site Dynamics

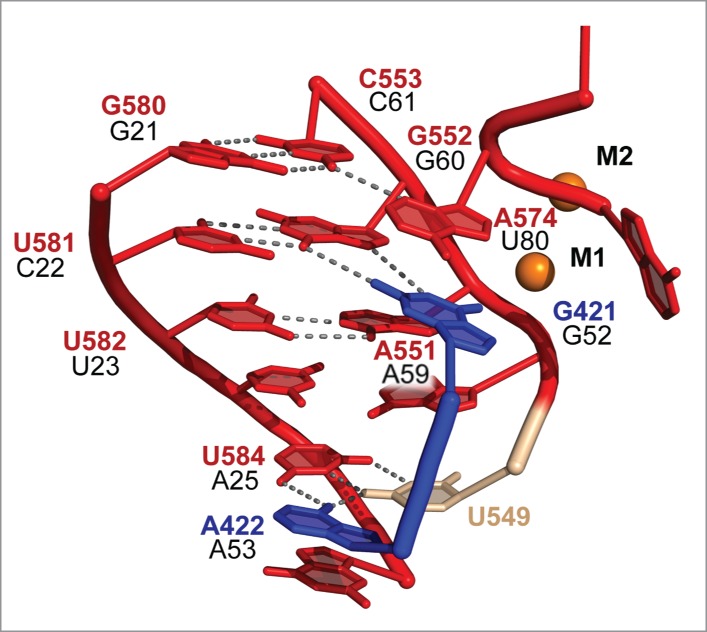

In previous IIC intron structures, the single-stranded linker between domains II and III (J2/3) forms base triple interactions with catalytic residues from DV.9,23 There is also evidence for similar base triples in the active site of the spliceosome.24 Interestingly, in the P.li.LSUI2 structure, one of the J2/3 residues (A422) is not engaged in a base triple with the catalytic triad, as was previously observed in the IIC structures. Instead, A422 is forming a base triple with residues from J4/5 (U549) and J5/6 (U584) (Fig. 2). This newly observed interaction of A422 introduces the possibility that the triple helix architecture in the catalytic core may change configuration between the 2 steps of splicing. Additionally, 7-deaza, 2,6-diaminopurine, and N6-methyl NAIM interferences were observed for the yeast aI5γ intron residue equivalent to A422.25 However, only the N6 amino group of A422 interacts with nearby bases in the post-catalytic P.li.LSUI2 structure, suggesting that this nucleotide may engage in additional transient interactions during the splicing reaction. Therefore, the observation that additional functional groups of residue A422 are important supports the hypothesis of a dynamic role for the J2/3 linker between splicing steps likely modulating catalysis. This hypothesis is also supported by crystal structures of the IIC intron showing that J2/3 disengages from the catalytic triad in the transition from the first to second step.23 J4/5 and J5/6 are also likely intimately involved in conformational rearrangements within the catalytic triad in supporting roles for J2/3. A similar interaction(s) may also be occurring within the spliceosome. Mutagenesis of the U584 analog in yeast (A25 in U2 snRNA) resulted in a 50% decrease in efficiency of the second step.26 Therefore, A25 plays a similar role in the second step as U584 in the P.li.LSUI2 intron. The lack of a first step splicing defect upon mutagenesis of A25 suggests that rearrangement of the base triples occurs in the transition between the 2 steps. This also alludes to the possibility that every stage of catalysis may have a unique arrangement of base triples in the catalytic core.

Figure 2.

P.li.LSUI2 core interactions and the proposed analogous spliceosomal residues. Coloring is consistent with the domains in Figure 1. P.li.LSUI2 residue numbers are shown in red, blue, and tan with proposed analogous U2 and U6 numbering in black. Spliceosomal numbering is from S. cerevisiae. In P.li.LSUI2, J2/3 residue A422 is disengaged from the catalytic triad (AGC) and instead forms a base triple with residues U549 and U584. Catalytic metals are shown as orange spheres and labeled M1 and M2.

3′ Splice Site Selection in the Second Step

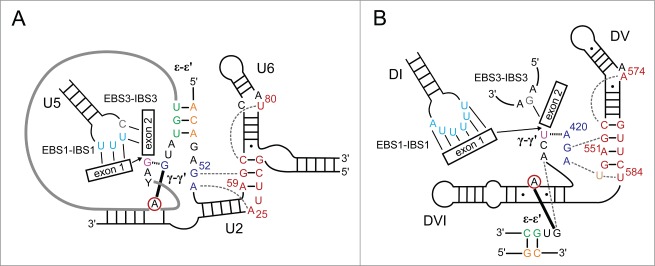

The EBS1-IBS1 and EBS2-IBS2 interactions in IIB introns function to correctly place the 5′ splice site in the active site for the first step. As is seen in the P.li.LSUI2 post-catalytic structure, these interactions remain engaged through the second step to position the 3′-hydroxyl nucleophile of the 5′ exon in the active site for the second step. It has been previously shown that deleting EBS1 from a group IIB intron and loop 1 from the U5 snRNA in yeast spliceosomes both result in an accurate and efficient first step, but stalling of the second step.27,28 This stalling can be relieved in group II introns upon the addition in trans of EBS1 or snRNA U5 loop 1.27 This suggests that both elements have a similar function in the group II intron and the spliceosome to tether the free 5′ exon to the active site between the 2 steps of splicing. The U5 snRNA has also been shown to base pair with the first 2 nucleotides of the 3′ exon (Fig. 3A).29,30 This interaction is equivalent to the EBS3-IBS3 interaction in group II introns (Fig. 3B) that forms prior to the second step to aid in the placement of the 3′ splice site, thus further extending the parallels between the 2 splicing systems.

Figure 3.

Comparison of spliceosomal and group II intron core structures prior to the second step. Analogous residues are shown in the same color and the color scheme is from ref. 10. DV residues are shown in red, J2/3 in blue, J4/5 in tan, EBS1 in light blue, EBS3 in gray, ϵ in orange, ϵ′ in green, and γ′ in purple. The conserved branch point residue is circled in red. Dotted gray lines denote base triples, solid black lines designate base pairing, the dashed black line indicates the γ-γ′ base pair, and the thick black line represents the 2′-5′ bond between the branch point residue and the first residue of the intron. Numbering is as in Figure 2. (A) Predicted spliceosomal core elements. Numbering is according to the S. cerevisiae U2 and U6 sequences. The intron is shown as a thick gray line. (B) Group II intron core arrangement. Numbering is as in Figure 2.

Prior to the second step, the γ-γ′ interaction must also form in group II introns to aid in positioning of the 3′ splice site. This highly conserved contact forms between the last nucleotide of the intron and the residue immediately 5′ to the J2/3 residues participating in base triples with the catalytic triad. This interaction brings the 3′ splice site in close spatial proximity to the catalytic metals in DV. In the post-catalytic P.li.LSUI2 structure, γ-γ′ is found to be disengaged indicating that it is a transient interaction that only exists during the presentation of the scissile phosphate of the 3′ splice site to the catalytic metals. Furthermore, the structure reveals a non-canonical pairing between the highly conserved G1 residue from the 5′ end and A620, which is the third nucleotide from the 3′ end of the intron (Fig. 1B). Therefore, the combination of both γ-γ′ and G1-A620 cooperate to precisely position the 3′ splice site within the core. In this case, the terminal nucleotides are not in direct contact with each other. However, in the spliceosome, it has been observed that the last nucleotide of the intron forms a non-canonical G-G base pair with the first nucleotide.31,32 As a result, the functions of γ-γ′ and G1-A620 are combined into a single entity involving direct interaction between the 5′ and 3′ ends.

Future Directions

The crystal structure of the P.li.LSUI2 intron in the post-catalytic lariat form has advanced our understanding of the structural requirements for group II intron splicing. However, this only represents the end product state and does not capture the entire spectrum of intermediates along the splicing pathway. For example, the pre-catalytic state would reveal the rationale for the conservation of the bulged adenosine nucleophile between group II introns and the spliceosome. At this stage of splicing, there must exist a defined binding pocket for this nucleobase that precisely positions the 2′-OH of the ribose sugar directly above the 5′ splice site. This structure would also reveal the specific nature of the conformational rearrangements involving DVI. Given that the distal tetraloop of DVI forms the static η-η′ interaction, the proximal region containing the bulged adenosine must either unwind or shift in order to engage π-π′ for the second step. Another intermediate of interest is the state prior to the second step of splicing, in which the 5′ exon is poised to attack the 3′ splice site. These intermediates may yet reveal additional unique catalytic triplex configurations for each stage of splicing. These base triple rearrangements would not be captured in the truncated IIC intron structure given that it was missing J5/6 and DVI. The triplex may have a similar dynamic nature in the spliceosome and assist with the forward progression of splicing.

The crystal structure of Prp8 has unexpectedly revealed an RT-like fold and domain organization similar to that seen in group II intron maturases, with Prp8 forming a cavity for the binding of the catalytic U2/U6 snRNA.22 The next major goal is to determine the structure of a group II intron ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex containing the cognate maturase. This protein facilitates splicing and allows retrotransposition reactions to occur in which the group II intron is able to insert into double-stranded DNA targets.1 The structure of a group II intron RNP would also allow a direct comparison with Prp8 to definitively establish structural homology. There is now increasing evidence that group II introns and the spliceosome share a common ancestor. These advancements in the study of group II intron structure and function can now be applied to further our understanding of the nuclear splicing machinery through investigation of the analogous interactions in the spliceosome.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

J.K.P. was supported by the UCSD Molecular Biophysics Training Program funded by NIH predoctoral training grant 5T32GM008326. This work was supported by a NIH grant 5R01GM102216 awarded to N.T.

References

- 1.Lambowitz AM, Zimmerly S. Group II introns: mobile ribozymes that invade DNA. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011; 3:a003616; PMID:20463000; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/cshperspect.a003616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peebles CL, Perlman PS, Mecklenburg KL, Petrillo ML, Tabor JH, Jarrell KA, Cheng HL. A self-splicing RNA excises an intron lariat. Cell 1986; 44:213-23; PMID:3510741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Veen R, Arnberg AC, van der Horst G, Bonen L, Tabak HF, Grivell LA. Excised group II introns in yeast mitochondria are lariats and can be formed by self-splicing in vitro. Cell 1986; 44:225-34; PMID:2417726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fica SM, Tuttle N, Novak T, Li NS, Lu J, Koodathingal P, Dai Q, Staley JP, Piccirilli JA. RNA catalyses nuclear pre-mRNA splicing. Nature 2013; 503:229-34; PMID:24196718; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature12734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valadkhan S, Mohammadi A, Wachtel C, Manley JL. Protein-free spliceosomal snRNAs catalyze a reaction that resembles the first step of splicing. RNA 2007; 13:2300-11; PMID:17940139; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.626207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valadkhan S, Mohammadi A, Jaladat Y, Geisler S. Protein-free small nuclear RNAs catalyze a two-step splicing reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106:11901-6; PMID:19549866; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.626207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rest JS, Mindell DP. Retroids in archaea: phylogeny and lateral origins. Mol Biol Evol 2003; 20:1134-42; PMID:12777534; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/molbev/msg135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toor N, Robart AR, Christianson J, Zimmerly S. Self-splicing of a group IIC intron: 5′ exon recognition and alternative 5′ splicing events implicate the stem-loop motif of a transcriptional terminator. Nucleic Acids Res 2006; 34:6461-71; PMID:17130159; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkl820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toor N, Keating KS, Taylor SD, Pyle AM. Crystal structure of a self-spliced group II intron. Science 2008; 320:77-82; PMID:18388288; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1153803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robart AR, Chan RT, Peters JK, Rajashankar KR, Toor N. Crystal structure of a eukaryotic group II intron lariat. Nature 2014; 514:193-7; PMID:25252982; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa M, Fontaine JM, Loiseaux-de Goer S, Michel F. A group II self-splicing intron from the brown alga Pylaiella littoralis is active at unusually low magnesium concentrations and forms populations of molecules with a uniform conformation. J Mol Biol 1997; 274:353-64; PMID:9405145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chanfreau G, Jacquier A. An RNA conformational change between the two chemical steps of group II self-splicing. EMBO J 1996; 15:3466-76; PMID:8670849 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li CF, Costa M, Michel F. Linking the branchpoint helix to a newly found receptor allows lariat formation by a group II intron. EMBO J 2011; 30:3040-51; PMID:21712813; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2011.214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anokhina M, Bessonov S, Miao Z, Westhof E, Hartmuth K, Luhrmann R. RNA structure analysis of human spliceosomes reveals a compact 3D arrangement of snRNAs at the catalytic core. EMBO J 2013; 32:2804-18; PMID:24002212; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2013.198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Query CC, Strobel SA, Sharp PA. Three recognition events at the branch-site adenine. EMBO J 1996; 15:1392-402; PMID:8635472 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bessonov S, Anokhina M, Will CL, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R. Isolation of an active step I spliceosome and composition of its RNP core. Nature 2008; 452:846-50; PMID:18322460; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schellenberg MJ, Dul EL, MacMillan AM. Structural model of the p14/SF3b155 • branch duplex complex. RNA 2011; 17:155-65; PMID:21062891; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.2224411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner IA, Norman CM, Churcher MJ, Newman AJ. Dissection of Prp8 protein defines multiple interactions with crucial RNA sequences in the catalytic core of the spliceosome. RNA 2006; 12:375-86; PMID:16431982; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.2229706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teigelkamp S, Newman AJ, Beggs JD. Extensive interactions of PRP8 protein with the 5′ and 3′ splice sites during splicing suggest a role in stabilization of exon alignment by U5 snRNA. EMBO J 1995; 14:2602-12; PMID:7781612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ismaili N, Sha M, Gustafson EH, Konarska MM. The 100-kda U5 snRNP protein (hPrp28p) contacts the 5′ splice site through its ATPase site. RNA 2001; 7:182-93; PMID:11233976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Query CC, Konarska MM. Suppression of multiple substrate mutations by spliceosomal prp8 alleles suggests functional correlations with ribosomal ambiguity mutants. Mol Cell 2004; 14:343-54; PMID:15125837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galej WP, Oubridge C, Newman AJ, Nagai K. Crystal structure of Prp8 reveals active site cavity of the spliceosome. Nature 2013; 493:638-43; PMID:23354046; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcia M, Pyle AM. Visualizing group II intron catalysis through the stages of splicing. Cell 2012; 151:497-507; PMID:23101623; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fica SM, Mefford MA, Piccirilli JA, Staley JP. Evidence for a group II intron-like catalytic triplex in the spliceosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2014; 21:464-71; PMID:24747940; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.2815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fedorova O, Pyle AM. Linking the group II intron catalytic domains: tertiary contacts and structural features of domain 3. EMBO J 2005; 24:3906-16; PMID:16252007; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madhani HD, Guthrie C. Randomization-selection analysis of snRNAs in vivo: evidence for a tertiary interaction in the spliceosome. Genes Dev 1994; 8:1071-86; PMID:7926788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hetzer M, Wurzer G, Schweyen RJ, Mueller MW. Trans-activation of group II intron splicing by nuclear U5 snRNA. Nature 1997; 386:417-20; PMID:9121561; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/386417a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Keefe RT, Norman C, Newman AJ. The invariant U5 snRNA loop 1 sequence is dispensable for the first catalytic step of pre-mRNA splicing in yeast. Cell 1996; 86:679-89; PMID:8752221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman AJ, Norman C. U5 snRNA interacts with exon sequences at 5′ and 3′ splice sites. Cell 1992; 68:743-54; PMID:1739979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Keefe RT, Newman AJ. Functional analysis of the U5 snRNA loop 1 in the second catalytic step of yeast pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J 1998; 17:565-74; PMID:9430647; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/17.2.565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker R, Siliciano PG. Evidence for an essential non-Watson-Crick interaction between the first and last nucleotides of a nuclear pre-mRNA intron. Nature 1993; 361:660-2; PMID:8437627; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/361660a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deirdre A, Scadden J, Smith CW. Interactions between the terminal bases of mammalian introns are retained in inosine-containing pre-mRNAs. EMBO J 1995; 14:3236-46; PMID:7621835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]