Abstract

Cell senescence, the permanent withdrawal of a cell from the cell cycle, is characterized by dramatic, cytological scale changes to DNA condensation throughout the genome. While prior emphasis has been placed on increases in heterochromatin, such as the formation of compact Senescent Associated Heterochromatin Foci (SAHF) structures, our recent findings showed that SAHF formation is preceded by the unravelling of constitutive heterochromatin into visibly extended structures, which we have termed Senescent Associated Distension of Satellites or SADS. Interestingly, neither of these marked changes in DNA condensation appear to be mediated by changes in canonical, heterochromatin-associated histone modifications. Rather, several observations suggest that these events may be facilitated by changes in LaminB1 levels and/or other factors that control higher-order chromatin architecture. Here, we review what is known about senescence-associated chromatin reorganization and present preliminary results using high-resolution microscopy techniques to show that each peri/centromeric satellite in senescent cells is comprised of several condensed domains connected by thin fibrils of satellite DNA. We then discuss the potential importance of these striking changes in chromatin condensation for cell senescence, and also as a model to provide a needed window into the higher-order packaging of the genome.

Keywords: centromeres, epigenetics, Higher-Order Heterochromatin Structure, lamin, SADS, SAHF, satellites, senescence

Abbreviations

- SADS

senescent associated distension of satellites

- SAHF

senescent associated heterochromatin foci

- SASP

senescence associated secretory phenotype.

Senescence and Heterochromatin: A Background

Senescence, first reported in cultured cells by Leonard Hayflick, is the irreversible exit of a viable cell from the cell cycle.1 This exit can be triggered by a variety of mechanisms including shortened telomeres, oxidative stress, and DNA damage and results in cells that persist and remain metabolically active indefinitely. In vivo, senescence functions to prevent cancer and the formation of malignant tumors by stopping damaged or precancerous cells from dividing, while also playing a role in the development of age-related disorders including osteoporosis and Alzheimer disease.2,3 In addition to depleting the proliferative cell population, senescent cells can secrete a characteristic profile of cytokines and other soluble factors that influence the behavior of surrounding cells known as the Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP).3 Senescent cells also undergo dramatic changes to DNA organization and chromatin packaging,4-6 processes that are thought to be essential for the maintenance of the senescent state.

DNA is organized into 2 cytologically and molecularly distinct compartments: structurally open euchromatin which is more actively transcribed and predominantly located in the interior of the mammalian nucleus, and transcriptionally repressed, compact heterochromatin often enriched at the nuclear and nucleolar periphery. Heterochromatin is further classified into 2 subtypes. The first is constitutive heterochromatin, defined as heterochromatin in all cell types and conditions, which includes tandem repetitive satellite repeats that form the structural domains at centromeres. The second is facultative heterochromatin which, despite being structurally similar to constitutive heterochromatin, consists of genes and genomic regions that are repressed in a developmental and cell-type specific manner, including the inactive X chromosome.7 In eukaryotic cells, several levels of chromatin packaging are formed which not only accomplish compaction, but regulate gene expression patterns required for cellular function. The first level of compaction entails the wrapping of 147 base pairs of naked DNA around a core histone complex forming repeating nucleosomal units.8 This gives rise to the 10 nm fiber,9,10 which is further organized into higher-order and often more compact structures. While much is known about the packaging of DNA at the nucleosome level, higher-order organization has remained more difficult to examine and poorly understood.

Consequently, one avenue of research in the field of chromatin biology is focused on deciphering the mechanisms facilitating the higher-order organization of DNA from the 10 nm fiber into the 10,000 fold more compact metaphase chromosome. We propose that insights into higher-order chromatin organization can be gleaned from the sweeping changes that accompany senescence, in particular the formation of Senescence Associated Heterochromatin Foci (SAHF) and Senescence Associated Distension of Satellites (SADS). Here, we review what is known about these structures, what these changes can tell us about higher-order chromatin organization, and present preliminary observations that offer new insights on these topics.

Heterochromatin Reorganization during Senescence: SAHF

SAHF are DNA dense heterochromatic regions which form at numerous sites throughout the nucleus of many senescent human cell types.4,5 Prior efforts have also demonstrated that each individual heterochromatic focus corresponds to one tightly compact chromosome territory marked by heterochromatin proteins and histone modifications associated with gene silencing, including HP1, H3K9Me3, H4 hypoacetylation, and MacroH2A.4,11-13 In addition, work of others and our own observations have shown that, when stained with DAPI, SAHF appear similar in size and shape to the inactive X chromosome found in female cells (Barr body) (Fig. 1),4,13 and contain several markers found on the inactive X chromosome.11,14,15 Similar to the Barr body, it has been shown that satellite sequences position at the periphery of SAHF.5,13,16 While most genes on the inactive X chromosome, independent of their silencing state, are located on the periphery or just outside of the human Barr body,16 the organization of genes relative to SAHF has not been extensively examined. However, prevailing thinking stems from analysis of 2 genes suggesting that SAHF formation contributes to cell-cycle withdrawal by sequestering and repressing genes necessary for the cell cycle within their interior,4,17 but there has been no further confirmation of this organization or the potential role of SAHF.

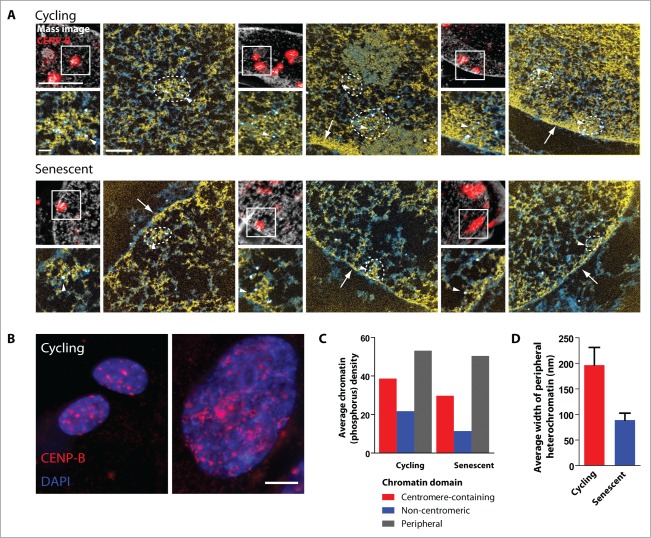

Figure 1.

SAHF appear similar in size and shape to the Barr body. (A) Non-senescent cell shows a more uniform distribution of DAPI-DNA staining. The XIST RNA signal (red) shows the location of the Barr body (DNA DAPI, blue) in a cycling Tig1 fibroblast. (B) The DNA DAPI staining from (A) is shown in gray scale to highlight the size and shape of the Barr body. (C–D) DNA DAPI staining (gray) of 2 senescent cells with SAHFs, note the heterochromatin foci in these cells are similar in size and shape to the Barr body from (B). (E) A SAHF positive senescent cells with XIST painting the Barr body.

In addition to not knowing the pattern of genic organization or even the specific sequences that are reorganized into SAHF, the precise role of SAHF in senescence remains poorly understood. For example, SAHF formation occurs relatively late during the onset of senescence, does not form in every senescent cell or cell type (e.g. not observed in murine or HGPS cells), and has not been observed in vivo.4,5,18-20 It has also been shown that SAHF formation can occur in response to the expression of oncogenic RAS in a senescence-independent manner.21 SAHF formation is thus an interesting model of chromatin repackaging that appears to represent a dramatic gain of higher-order heterochromatin. However, its failure to occur early and consistently in response to senescence brings into question the importance of SAHF in the senescence process.

Loss of “Constitutive” Satellite Heterochromatin in Senescence: SADS

In contrast to SAHF formation, there are global changes that occur during senescence that are more consistent with a loss of heterochromatin. For example, it has been shown that levels of the chromatin remodeling protein HMGA, which is typically associated with open regions of DNA, are increased in senescent cells, whereas the nucleosome linker histone, H1, is lost.13,15 Furthermore, patterns of trasposable element activation and genome-wide methylation in senescent cells have been reported to resemble those seen in cancer cells,22,23 where the epigenome is thought to be more open and less heterochromatic.24,25

Additional loss of condensed heterochromatin in cell senescence was shown by our recent discovery that all of the normally compact α-satellite and satellite II sequences at each peri/centromere dramatically distend early in the senescence process. This phenomenon, which we termed SADS (Senescence-Associated Distension of Satellites), was first observed in a subset of Tig-1 fibroblasts hybridized with probes to α-satellite or satellite II repeats (Fig. 2A, B).5 Upon further characterization, this distension was shown to be both specific and extremely consistent for senescent cells based not only on SA-β-galactosidase staining, but also on BrdU analysis of single cells for both replication and the presence of SADS.5 SADS were also observed in all forms of senescence induction examined, including by the Ras oncogene, oxidative stress, the upregulation of the ubiquitin ligase SMURF2, and replicative senescence.5 Unlike SAHF, SADS were seen in all senescent human cell lines, in murine cells (MEFs), in vivo in tissue sections of a benign, human Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PIN), and in Hutchinson Guilford Progeria cells.5 These data allow us to conclude that SADS is a consistent, potentially ubiquitous new marker of senescence in single cells, but it also raises the intriguing possibility that the reorganization of centromeric chromatin may be an integral part of the senescence process.

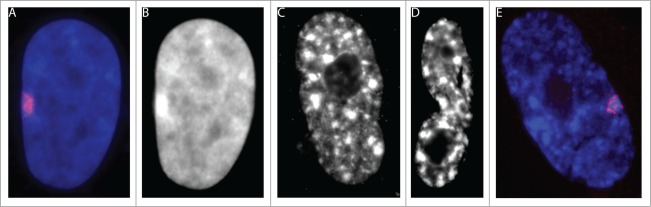

Figure 2.

Closer Inspection of Satellite Structure Suggests the Presence of DNA Organized into Domains. (A–B) Cycling (A) and senescent (B) Tig-1 fibroblasts have dramatically different α-satellite (green) and satellite II (red) organization at the resolution of light microscopy. However, closer inspection of gray scale images reveals evidence of organization within each satellite signal, whereby senescent satellites comprise globular domains linked together by threads of more distended DNA. (C–D) Using a probe specific to chromosome 17 α-satellite sequence (green) the signal appears punctate in a cycling cell (c) but distends so that individual domains or globules of still condensed DNA become more visible in senescent cells (D). (E) Confocal (left) and super resolution STED images (right) of chromosome 17 α-satellite in a cycling cell. These images are shown below in gray scale to increase visibility of more condensed domains (yellow arrows). (F) Three chromosome 17 peri/centromeric α-satellite signals (green) from 2 different cells. The confocal images are on the left and the super resolution image is on the right. The yellow arrows point to some of the easily visible domains that are linked together by threads of DNA.

While the specific mechanisms that underlie SADS formation remain to be determined, this radical departure from “constitutive” condensed structures of centromere-associated heterochromatin may serve to promote the permanence of the senescent state by blocking cell division. Consistent with this potential functional role, it is important to note that SADS formation occurs early in senescence (beginning within 48 hours of the final cell cycle) and prior to SAHF formation and other changes, which occur later.5,13 We also showed that CENP-B remains bound throughout the distended α-satellite repeats whereas the centromere specific histone H3 variant, CENP-A (CenH3), does not visibly distend but decreases in senescent cells.5,26 Whether other centromere-associated proteins are impacted by SADS formation or the distension contributes to blocking the continuation of the cell cycle, potentially by disrupting the structural integrity of centromeres, remains to be addressed.

SADS and the Unraveling of Higher-Order Chromatin Folding

The formation of SADS also represents a potentially unprecedented higher-order unfolding of the chromatin fiber on a scale visible by light microscopy. The evidence that this is “higher-order unfolding” rather than small-scale DNA decondensation (as occurs in transcriptional activation) is 2-fold. First, the compaction ratio of distended α-satellite DNA was found to be a minimum of 5 times less than α-satellite in cycling cells. In fact, the compaction ratio of SADS approached previously measured levels for genic DNA.27 The loss of compaction, however, did not correlate with increased expression of satellite RNA, and is distinct in both scale and function from the “opening” of chromatin linked to transcription. While increases in satellite RNA expression have been reported 6–8 weeks after the induction of senescence,22 we examined cells within 10 days, which could account for the contrasting results. Second, we noted that both the DNA methylation pattern and the enrichment of several canonical heterochromatin modifications (H3K9Me3, H3K27Me3, and to a slightly lesser extent H3K4Me3) in α-satellite regions did not change during senescence despite the dramatic repackaging.5 This leads us to suggest that SADS likely represent a higher-order unfolding of chromatin packaging, above the level of nucleosome modifications, which may be mediated by changes to nuclear architectural proteins such as lamins, as discussed below.

Changes in DNA Organization Occur while Many Histone Marks Remain

Given that SAHF and SADS represent, large, visible, cytological changes in DNA condensation, it was expected that the epigenetic landscape of histone modifications on genomic sequences would change dramatically. Surprisingly, ChIP-Seq analysis from Chandra et al. reported that there was little change in the distribution of several heterochromatin marks on DNA during SAHF formation,28 and this remained true when we used their data to examine the epigenetic profile of satellite sequences during senescence.5 This implies that these marks are not redistributed throughout the genomic DNA during senescence as might be expected; rather, DNA still containing these heterochromatin modifications aggregates to form heterochromatin bodies (SAHF), or, in the case of satellite DNA, distends dramatically (SADS).

The question remains open, however, because recent work appears to contrast with conclusions based on the data from Chandra et al. Specifically, large scale changes to the chromatin landscape of both H3K27Me3 and H3K4Me3 have been observed, in which regions of these modifications in senescent cells are either increased to form “mesas” or decreased to form “canyons.”29 These results could relate to earlier microarray data showing that genes with differential expression in senescent cells group together in blocks along the length of the chromosome.30 We note, however, that in Shah et al. (Supplemental Figure 5) the percentage of the genome either gaining or losing each histone modification is small and western blot analysis for histone modifications shows no change in the overall level of these modifications during senescence.13,29 It is therefore possible to speculate that small changes in histone modification levels across the genome teased out by Shah et al. to form the canyons and mesas within senescent cells went undetected or unnoted by Chandra et al., who were examining the genome for the type of gross overall changes that might be expected due to the large structural changes observed during SAHF formation. Hence, we suggest that both of these studies are indeed compatible, and that these findings, together, with the large-scale cytological chromatin unfolding inherent in SADS, point to the likelihood that SADS formation involves changes to the higher-order packaging of the genome.

The Nuclear Lamina and its role in Heterochromatin Organization during Senescence

Lamin proteins are key structural components throughout the nucleus which together form the nuclear lamina underlying the nuclear envelope. These proteins have long been implicated in the organization of chromatin into higher-order structures.31 Since lamins interact with the Retinoblastoma protein (Rb), a regulator of both senescence and heterochromatin, and LaminB1 levels decline dramatically during senescence,32-36 the nuclear lamina may be a key player in both SADS and SAHF formation. In fact, it was shown that SAHF formation is facilitated by a decrease in LaminB1,6 and it was recently speculated that SAHF are comprised of DNA that in cycling cells is enriched for lamin associated domains.37 This is noteworthy and leads us to suggest that in SAHF-positive cells, the organization of heterochromatin appears to be flipped inside out as the peripheral heterochromatin compartment found in cycling cells may be broken down and reorganized into SAHF (Figs. 2 and 3). We also noted that the linearized satellite signals often contact and appear to terminate at the nuclear periphery, and it has been shown that pericentric heterochromatin (satellite DNA) is enriched in Lamin-Associated Domains (LADs)38 and the disruption of the nuclear lamina can alter satellite organization.39 This evidence suggests that satellites are tethered to the lamina, which would also be consistent with recent reports showing that in senescence LaminB1 is depleted from regions enriched in H3K9Me3,6 a histone modification enriched in satellite DNA.40,41 Interestingly, single cell analysis showed that LaminB1 loss was evident before SADS formation in over half of the cells, indicating that LaminB1 depletion may be one of the factors facilitating the repackaging of satellite DNA during senescence.5 Considering that previous studies have also shown that cohesins are not recruited to pericentromeric DNA during senescence42 and that in Drosophila the loss of condensin II, which plays a role in higher-order chromosome compaction and organization, results in a 10-fold increase in chromosome length,43 we suggest that future studies of SADS should examine the loss of these and other architectural proteins in combination with the loss of LaminB1.

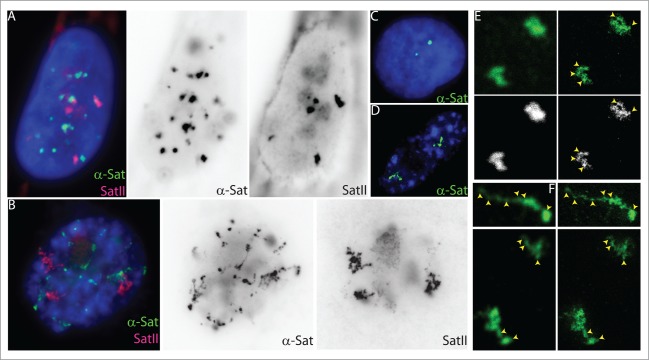

Figure 3.

Underlying Chromatin Structure of Centromeres. (A) Correlative light microscopy and electron spectroscopic imaging (ESI) of 3 representative cycling and 2 senescent WI-38 cells. Cells were labeled with gold-conjugated CENP-B antibodies and prepared for ESI. CENP-B fluorescence (red) was overlaid onto the low magnification mass sensitive image (black and white) generating the correlative image (top left panel, scale bar, 10 μm). ESI micrographs of the CENP-B-containing structure (white box) are shown (scale bar 0.5 μm). Approximate boundaries of the centromere-containing region are indicated by a dashed line. Arrowheads indicate gold particles labeling CENP-B. Arrows point to the heterochromatin at the edge of the nuclear envelope (periphery). A higher magnification image of the region marked by the dashed line is shown under the correlative image (bottom left panel, scale bar, 0.2 μm). In all ESI images, chromatin is pseudo colored yellow and protein-based structures cyan. (B) CENP-B labeling (red) of cycling and senescent WI-38 cells. Scale bar, 5 μm. (C) Average phosphorus density of the centromeric-containing and surrounding chromatin, and heterochromatin at the periphery of the nuclear envelope of the images shown in (A). (D) Average thickness of the peripheral heterochromatin of the images shown in (A) was determined by measuring the number of pixels of the compact chromatin along the edge of the nuclear membrane (ImageJ). Measurements were taken from 2–4 regions, and excluded centromeric-containing chromatin and nuclear pores.

Preliminary Insights from a Closer Inspection of Satellite Structure

To further our understanding of the higher-order chromatin changes that occur during senescence, we used a super-resolution light microscopy technique, STED, to image SADS at a 30 nm resolution. While these observations are preliminary, they raise the possibility that in both cycling and senescent cells, satellite DNA may be organized into tightly compacted domains or “globules” spaced by linker regions (Fig. 2). The spacing between the compact domains, however, appears different between the 2 cell states, such that in senescent cells globular domains become further apart rather than clustered into a compact conformation. We hypothesize that in cycling cells, domains or globules of satellite DNA may be held in close proximity by an unknown factor (as discussed at the end of the previous section) that facilitates the higher-order organization of each satellite. During the senescence process, these factors may be lost from satellites, allowing the DNA linking the globular domains to extend into more linear conformations. If this organization of satellite DNA proves correct, it would provide the first direct visual evidence of such a higher-order organization of chromatin. While satellites represent distinct regions of the genome, these globular domains may be compatible with proposed models of DNA folding in Topological Associated Domains (TADs) predicted by chromatin conformation analysis.44-47

To examine the underlying chromatin structure of satellite-containing chromatin at high molecular resolution, we also performed a preliminary analysis of centromeres using electron spectroscopic imaging (ESI). ESI is a specialized form of energy-loss transmission electron microscopy that provides a direct and quantitative measurement of chromatin density.48,49 For example, integrative phosphorus and nitrogen density analyses of ESI micrographs of senescent IMR90 cells revealed differences in chromatin compaction within SAHF as well as between SAHF and the surrounding chromatin.28 Hence, we examined the underlying chromatin structure of satellite-containing heterochromatin by obtaining ESI micrographs from nuclei of cycling and senescent WI-38 fibroblasts labeled with gold-conjugated CENP-B antibodies. As these images were obtained from 70 nm sections, we were unable to observe the linear chromatin fibers linking the compact domains. We were, however, able to observe the CENP-B-containing compact structures reminiscent of the globules discussed above. Consequently, we determined the average chromatin density of 3 distinct regions in both cycling and senescent cells: CENP-B-enriched centromeres, chromatin surrounding the CENP-B-defined region, and heterochromatin at the nuclear periphery (Fig. 3A, C). We found that the average chromatin density in centromeres is similar in cycling and senescent cells. This observation is consistent with our current hypothesis that the discrete satellite-containing structures seen in cycling cells are comprised of globules tightly packed together that become more spaced out in senescent cells, giving rise to the distended patterns seen in SADS.

We also observed differences in the chromatin surrounding centromeres in the cycling and senescent cells examined. In the senescent cells, non-centromeric chromatin (not including SAHF) appears as a more open mesh of loosely dispersed fibers, whereas the chromatin surrounding centromeres in cycling cells is more densely packed. Indeed, the preliminary analysis of the average integrative phosphorus density of this surrounding chromatin reflects this observation as it is greater in cycling cells (21.7) compared to senescent cells (11.4), representing a 1.9-fold change (Fig. 3A, C).

With respect to peripheral chromatin, we observed that the thickness of the heterochromatin compartment at the nuclear periphery is reduced in the senescent cells examined here with an average thickness of 100 nm compared to the 200 nm thickness observed in cycling cells (Fig. 3A, D). Despite the thinning of peripheral heterochromatin, the chromatin compaction within this region did not appear to change as the average integrated phosphorus values are 53 in cycling and 50 in senescent cells (Fig. 3A, C).However, this thinning of peripheral heterochromatin in senescent cells would be consistent with the previously mentioned possibility that peripheral heterochromatin is relocating to the interior of senescent nuclei and this process could be facilitated, at least in part, by LaminB1 depletion.37 Interestingly, peri/centric heterochromatin often appeared less compact than peripheral heterochromatin in both cycling and senescent cells, suggesting that not all constitutive heterochromatin domains comprise the most highly compact chromatin in the nucleus (Fig. 3A, C).

It should also be noted that although the volume of a senescent nucleus is often larger than that of a cycling cell,5,50 we did not observe a clear correlation between nuclear volume and average integrative phosphorus intensity values. Since the observed fold-changes in average chromatin compaction are domain specific, the dispersed chromatin surrounding centromeres in senescent nuclei may not solely be attributed to increased nuclear size, but rather to global changes in chromatin organization. Taken together, these results illustrate numerous differences in chromatin organization between cycling and senescent cells that provide a rich opportunity to reveal principles of higher order chromatin architecture and advance our understanding of cell senescence.

Conclusion

Senescence is accompanied by a multitude of changes to the packaging of DNA, including the consistent loss of higher-order chromatin packaging during SADS formation, the frequent reorganization of chromatin into SAHF, and the reduction of LaminB1. These changes are a fundamental aspect of senescence biology, and may contribute to the permanence of the senescent state, but they also provide an advantageous model to study higher-order chromatin packaging. Since the packaging and organization of DNA from the 10 nm fiber to the metaphase chromosome remains a mystery, new ways to examine these questions are needed. We suggest the dramatic changes that occur to heterochromatin during senescence provide an opportunity to enable new insights into the organization of higher-order heterochromatin.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Hayflick L. The limited in vitro lifetime of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res 1965; 37:614-36; PMID:14315085; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0014-4827(65)90211-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Deursen JM. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature 2014; 509:439-46; PMID:24848057; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campisi J. Aging, Cellular Senescence, and Cancer. Ann Rev Physiol 2013; 75:null; PMID:23140366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narita M, Nunez S, Heard E, Lin AW, Hearn SA, Spector DL, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell 2003; 113:703-16; PMID:12809602; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00401-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson EC, Manning B, Zhang H, Lawrence JB. Higher-order unfolding of satellite heterochromatin is a consistent and early event in cell senescence. J Cell Biol 2013; 203(6):929-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadaie M, Salama R, Carroll T, Tomimatsu K, Chandra T, Young ARJ, Narita M, Pérez-Mancera PA, Bennett DC, Chong H, et al.. Redistribution of the Lamin B1 genomic binding profile affects rearrangement of heterochromatic domains and SAHF formation during senescence. Gen Dev 2013; 27:1800-8; PMID:23964094; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.217281.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trojer P, Reinberg D. Facultative Heterochromatin: Is There a Distinctive Molecular Signature? Mol Cell 2007; 28:1-13; PMID:17936700; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornberg RD. Chromatin structure: a repeating unit of histones and DNA. Science 1974; 184:868-71; PMID:4825889; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.184.4139.868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olins AL, Olins DE. Spheroid Chromatin Units (ν Bodies). Science 1974; 183:330-2; PMID:4128918; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.183.4122.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodcock CL, Safer JP, Stanchfield JE. Structural repeating units in chromatin. I. Evidence for their general occurrence. Exp Cell Res 1976; 97:101-10; PMID:812708; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90659-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang R, Poustovoitov MV, Ye X, Santos HA, Chen W, Daganzo SM, Erzberger JP, Serebriiskii IG, Canutescu AA, Dunbrack RL, et al.. Formation of MacroH2A-containing senescence-associated heterochromatin foci and senescence driven by ASF1a and HIRA. Dev Cell 2005; 8:19-30; PMID:15621527; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams PD. Remodeling of chromatin structure in senescent cells and its potential impact on tumor suppression and aging. Gene 2007; 397:84-93; PMID:17544228; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Funayama R, Saito M, Tanobe H, Ishikawa F. Loss of linker histone H1 in cellular senescence. J Cell Biol 2006; 175:869-80; PMID:17158953; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200604005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chadwick BP, Willard HF. Chromatin of the Barr body: histone and non-histone proteins associated with or excluded from the inactive X chromosome. Hum Mol Genet 2003; 12:2167-78; PMID:12915472; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/hmg/ddg229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narita M, Krizhanovsky V, Nunez S, Chicas A, Hearn SA, Myers MP, Lowe SW. A novel role for high-mobility group a proteins in cellular senescence and heterochromatin formation. Cell 2006; 126:503-14; PMID:16901784; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clemson CM, Hall LL, Byron M, McNeil J, Lawrence JB. The X chromosome is organized into a gene-rich outer rim and an internal core containing silenced nongenic sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:7688-93; PMID:16682630; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0601069103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang R, Chen W, Adams PD. Molecular Dissection of Formation of Senescence-Associated Heterochromatin Foci. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27:2343-58; PMID:17242207; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.02019-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy A, McBryan T, Enders G, Johnson F, Zhang R, Adams P. Senescent mouse cells fail to overtly regulate the HIRA histone chaperone and do not form robust Senescence Associated Heterochromatin Foci. Cell Division 2010; 5:16; PMID:20569479; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1747-1028-5-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreiling JA, Tamamori-Adachi M, Sexton AN, Jeyapalan JC, Munoz-Najar U, Peterson AL, Manivannan J, Rogers ES, Pchelintsev NA, Adams PD, et al.. Age-associated increase in heterochromatic marks in murine and primate tissues. Aging Cell 2011; 10:292-304; PMID:21176091; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00666.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosar M, Bartkova J, Hubackova S, Hodny Z, Lukas J, Bartek J. Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci are dispensable for cellular senescence, occur in a cell type- and insult-dependent manner and follow expression of p16 (ink4a). Cell Cycle 2011; 10:457-68; PMID:21248468; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.10.3.14707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Micco R, Sulli G, Dobreva M, Liontos M, Botrugno OA, Gargiulo G, dal Zuffo R, Matti V, d'Ario G, Montani E, et al.. Interplay between oncogene-induced DNA damage response and heterochromatin in senescence and cancer. Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13:292-302; PMID:21336312; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Cecco M, Criscione SW, Peckham EJ, Hillenmeyer S, Hamm EA, Manivannan J, Peterson AL, Kreiling JA, Neretti N, Sedivy JM. Genomes of replicatively senescent cells undergo global epigenetic changes leading to gene silencing and activation of transposable elements. Aging Cell 2013: PMID:23360310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cruickshanks HA, McBryan T, Nelson DM, Vanderkraats ND, Shah PP, van Tuyn J, Singh Rai T, Brock C, Donahue G, Dunican DS, et al.. Senescent cells harbour features of the cancer epigenome. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15:1495-506; PMID:24270890; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pageau GJ, Hall LL, Ganesan S, Livingston DM, Lawrence JB. The disappearing Barr body in breast and ovarian cancers. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7:628-33; PMID:17611545; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carone DM, Lawrence JB. Heterochromatin instability in cancer: From the Barr body to satellites and the nuclear periphery. Seminars in Cancer Biology 2013; 23:99-108; PMID:22722067; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maehara K, Takahashi K, Saitoh S. CENP-A Reduction Induces a p53-Dependent Cellular Senescence Response To Protect Cells from Executing Defective Mitoses. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2010; 30:2090-104; PMID:20160010; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.01318-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence JB, Singer RH, McNeil JA. Interphase and metaphase resolution of different distances within the human dystrophin gene. Science 1990; 249:928-32; PMID:2203143; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.2203143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandra T, Kirschner K, Thuret J-Y, Pope Benjamin D, Ryba T, Newman S, Ahmed K, Samarajiwa Shamith A, Salama R, Carroll T, et al.. Independence of Repressive Histone Marks and Chromatin Compaction during Senescent Heterochromatic Layer Formation. Mol Cell 2012; 47(2):203-14; PMID:22795131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah PP, Donahue G, Otte GL, Capell BC, Nelson DM, Cao K, Aggarwala V, Cruickshanks HA, Rai TS, McBryan T, et al.. Lamin B1 depletion in senescent cells triggers large-scale changes in gene expression and the chromatin landscape. Genes & Development 2013; 27:1787-99; PMID:23934658; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.223834.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Pan KH, Cohen SN. Senescence-specific gene expression fingerprints reveal cell-type-dependent physical clustering of up-regulated chromosomal loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100:3251-6; PMID:12626749; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.2627983100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butin-Israeli V, Adam SA, Goldman AE, Goldman RD. Nuclear lamin functions and disease. Trends in Genetics 2012; 28:464-71; PMID:22795640; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tig.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimi T, Butin-Israeli V, Adam SA, Hamanaka RB, Goldman AE, Lucas CA, Shumaker DK, Kosak ST, Chandel NS, Goldman RD. The role of nuclear lamin B1 in cell proliferation and senescence. Genes Dev 2011; 25(24):2579-93; PMID:22155925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freund A, Laberge R-M, Demaria M, Campisi J. Lamin B1 loss is a senescence-associated biomarker. Mol Biol Cell 2012; 23(11):2066-75; PMID:22496421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalo S, Garcia-Cao M, Fraga MF, Schotta G, Peters AHFM, Cotter SE, Eguia R, Dean DC, Esteller M, Jenuwein T, et al.. Role of the RB1 family in stabilizing histone methylation at constitutive heterochromatin. Nat Cell Biol 2005; 7:420-8; PMID:15750587; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorner D, Gotzmann J, Foisner R. Nucleoplasmic lamins and their interaction partners, LAP2α, Rb, and BAF, in transcriptional regulation. FEBS Journal 2007; 274:1362-73; PMID:17489094; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05695.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marji J, O'Donoghue SI, McClintock D, Satagopam VP, Schneider R, Ratner DJ. Worman H, Gordon LB, Djabali K. Defective lamin A-Rb signaling in hutchinson-gilford progeria syndrome and reversal by farnesyltransferase inhibition. PLoS One 2010; 5:e11132; PMID:20559568; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0011132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chandra T, Ewels Philip A, Schoenfelder S, Furlan-Magaril M, Wingett Steven W, Kirschner K, Thuret J-Y, Andrews S, Fraser P, Reik W. Global Reorganization of the Nuclear Landscape in Senescent Cells. Cell Reports 2015; 10:471-83; PMID:25640177; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guelen L, Pagie L, Brasset E, Meuleman W, Faza MB, Talhout W, Eussen BH, de Klein A, Wessels L, de Laat W, et al.. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature 2008; 453:948-51; PMID:18463634; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taimen P, Pfleghaar K, Shimi T, Möller D, Ben-Harush K, Erdos MR, Adam SA, Herrmann H, Medalia O, Collins FS, et al.. A progeria mutation reveals functions for lamin A in nuclear assembly, architecture, and chromosome organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2009; 106:20788-93; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0911895106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikkelsen TS, Ku M, Jaffe DB, Issac B, Lieberman E, Giannoukos G, Alvarez P, Brockman W, Kim TK, Koche RP, et al.. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature 2007; 448:553-60; PMID:17603471; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenfeld J, Wang Z, Schones D, Zhao K, DeSalle R, Zhang M. Determination of enriched histone modifications in non-genic portions of the human genome. BMC Genomics 2009; 10:143; PMID:19335899; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2164-10-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Geesman GJ, Hostikka SL, Atallah M, Blackwell B, Lee E, Cook PJ, Pasaniuc B, Shariat G, Halperin E, et al.. Inhibition of activated pericentromeric SINE/Alu repeat transcription in senescent human adult stem cells reinstates self-renewal. Cell Cycle 2011; 10:3016-30; PMID:21862875; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.10.17.17543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bauer CR, Hartl TA, Bosco G. Condensin II Promotes the Formation of Chromosome Territories by Inducing Axial Compaction of Polyploid Interphase Chromosomes. PLoS Genet 2012; 8:e1002873; PMID:22956908; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibcus Johan H, Dekker J. The Hierarchy of the 3D Genome. Mol Cell 2013; 49:773-82; PMID:23473598; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baù D, Sanyal A, Lajoie BR, Capriotti E, Byron M, Lawrence JB, Dekker J, Marti-Renom MA. The three-dimensional folding of the α-globin gene domain reveals formation of chromatin globules. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011; 18:107-14; PMID:21131981; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsmb.1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao Suhas SP, Huntley Miriam H, Durand Neva C, Stamenova Elena K, Bochkov Ivan D, Robinson James T, Sanborn Adrian L, Machol I, Omer Arina D, Lander Eric S, et al.. A 3D Map of the Human Genome at Kilobase Resolution Reveals Principles of Chromatin Looping. Cell 2014; 159:1665-80; PMID:25497547; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dixon JR, Selvaraj S, Yue F, Kim A, Li Y, Shen Y, Hu M, Liu JS, Ren B. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 2012; 485:376-80; PMID:22495300; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature11082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bazett-Jones DP, Hendzel MJ. Electron Spectroscopic Imaging of Chromatin. Methods 1999; 17:188-200; PMID:10075896; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/meth.1998.0729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dellaire G, Nisman R, Bazett-Jones DP. Correlative light and electron spectroscopic imaging of chromatin in situ. Methods Enzymol 2004; 375:456-78; PMID:14870683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. The essence of senescence. Gen Dev 2010; 24:2463-79; PMID:21078816; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.1971610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]