Abstract

Low-cost, translatable interventions to promote adherence in adolescents with type 1 diabetes are needed. This study evaluated a brief physician-delivered intervention designed to increase parent-adolescent communication about blood glucose (BG) monitoring. Thirty adolescent/parent dyads completed baseline questionnaires and received the physician-delivered intervention. Participants completed follow-up questionnaires at 12 weeks; HbA1c and glucometer data were abstracted from medical charts. Parent-reported conflict surrounding diabetes management decreased from pre- to post-intervention. Participants who reported adhering to the intervention plan (n=15) demonstrated an increase in BG monitoring frequency and trends in improved HbA1c and parental diabetes collaboration from pre- to post-intervention. Participants and physicians reported overall satisfaction with the program. Results demonstrate initial feasibility as well as a trend towards improvement in diabetes-specific health indicators for parent/adolescent dyads who adhered to program components. Frequent joint review of glucometer data can be a useful strategy to improve T1D-related health outcomes and parent-adolescent communication.

Keywords: adolescence, blood glucose self-monitoring, communication, patient adherence

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is one of the most common childhood chronic illnesses, affecting 1:400 youth under 20 years.1 For youth with T1D, early adolescence is a critical developmental period where the main responsibility for T1D care transitions from the parent(s) to shared responsibility between parent(s) and child.2 Adolescents are at risk for poorer glycemic control and greater fluctuation in regimen adherence, with many experiencing a deterioration of T1D management during this time.3 More frequent blood glucose (BG) monitoring is an important component of T1D care associated with better glycemic control;4 however, a high proportion of adolescents with diabetes exhibit a decrease in BG monitoring and related increase in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) across adolescence.5

Healthy parent-child communication and consistent parental monitoring of T1D care has a direct effect on adolescent regimen adherence and results in better glycemic outcomes.6,7 However, it is important that parental involvement is balanced to respect an adolescent’s growing autonomy while also providing continued support and oversight. Parental over-involvement or under-involvement can lead to family conflict, which can have unwanted, adverse effects on T1D management.8 Much of this family conflict tends to revolve around BG monitoring, with adolescents potentially viewing parental involvement as controlling, overprotective, or punitive.9 Adolescents who fail to achieve BG values within their target range can feel disappointed, guilty, or angry, and have even cited a desire to avoid a negative reaction from parents as a reason for not checking BG levels.10,11

A positive relationship between physicians and adolescent patients is associated with greater feelings of mastery for T1D care and positive health outcomes.12 Physicians are a trusted member of a patient’s health care team and patients generally value their expert advice. As a resource that is external to the family system, physicians are in a unique position of authority to improve disease management and mediate potential conflict between parents and adolescents.13 Given the potential benefits of the physician-patient relationship, physician-delivered interventions may be a successful option to improve T1D health behaviors, including BG monitoring and parent-adolescent communication, in adolescents with T1D. Further, a low-intensity physician-delivered intervention can support the integration of behavioral strategies into routine diabetes care. Accessible technologies such as mobile text messaging and email also offer opportunities to reinforce intervention concepts using technology already well-integrated into adolescents’ and parents’ daily lives.14

The Checking In program was created to provide physicians with brief, low-cost intervention tools to promote positive parent-adolescent communication about BG monitoring. Physicians delivered the pilot intervention materials during a routine medical clinic visit and intervention content was reinforced through 12 weeks of brief text messages (or e-mails) delivered to parents and adolescents. This study evaluated the Checking In program pilot, including changes pre- to post-intervention in: 1) T1D health indicators (HbA1c, BG monitoring frequency, mean BG level, and adolescent- and parent-reported adherence); 2) parental monitoring of and involvement in T1D care; and 3) diabetes-specific family conflict. It was hypothesized that participation in the Checking In intervention pilot would result in improved T1D health, including lower HbA1c, more frequent BG monitoring, lower mean BG level, and increased parent- and adolescent-reported adherence; increased parental monitoring of and involvement in diabetes care; and decreased family conflict related to diabetes. It was also hypothesized that parents, adolescents, and physicians would be satisfied with their participation in the Checking In program.

Methods

Participants

Study participants included 30 adolescents ages 11–15 and a primary caregiver recruited from a large Mid-Atlantic pediatric hospital. Participants were excluded if they had been diagnosed with T1D for less than 1 year, had a diagnosis of a developmental disability (e.g. autism) or severe medical condition that would limit their participation, and/or if they did not adequately understand, speak, and read English. Potential participants also were excluded from the study by lack of parental consent.

Procedure

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the study site. Potentially eligible participants were identified by reviewing clinic lists and were mailed recruitment letters along with a postcard that could be returned if the family did not wish to be contacted. Research team members contacted potential participants to assess interest and eligibility. Participants who expressed interest in the project met with a research team member during a regularly scheduled clinic appointment to complete consent and study procedures. Enrolled participants completed baseline questionnaires, received the Checking In intervention which included physician-delivered content during a medical clinic visit and 12 weeks of text message or e-mail boosters (optional), and completed follow-up questionnaires online via REDCap, a secure data capture system,15 12 weeks post-intervention. HbA1c values and BG data were taken from medical chart review from the clinic visits closest to baseline and follow-up questionnaire completion.

As this was a pilot study, all participants were provided with the Checking In intervention. The majority of the Checking In intervention was conducted during the adolescent’s routine medical clinic visit for T1D management. The intervention was developed by the psychosocial members of the diabetes team; intervention targets and content were guided by health care provider-identified barriers to optimal diabetes management. Two physicians agreed to deliver the pilot intervention and participated in a 60-minute training to review intervention content and strategies for delivery. In addition to topics ordinarily covered during a routine diabetes care visit, the physician provided the family with psychoeducational materials and delivered a scripted intervention highlighting: the importance of continued parental monitoring of diabetes care during adolescence; how to operate standard glucometers; and specific steps for parents and adolescents to jointly hold a “3 minute meeting” (3MM) at least three times per week to review BG data and briefly problem solve any concerns related to BG levels. Parents and adolescents were given a one page handout that described the purpose of 3MMs, how to hold a 3MM, and the goal of holding 3MMs 3 times/week. To assess for fidelity to the treatment script, a random subset of visits (n=7) were audiotaped to ensure consistency of intervention delivery. Participants were able to request that any session not be taped without affecting participation in the project. Study staff sent weekly text message or e-mail reminders for 12 weeks post-intervention to provide brief reminders about intervention content, including consistent scheduling of 3MMs. These texts were sent to the parents and/or adolescents who had cell phones and were interested in receiving them; parents and/or teens could choose to receive the booster messages via e-mail instead of text message if preferred. All texts were one-way and sent via a free text messaging program available online (Pinger®).

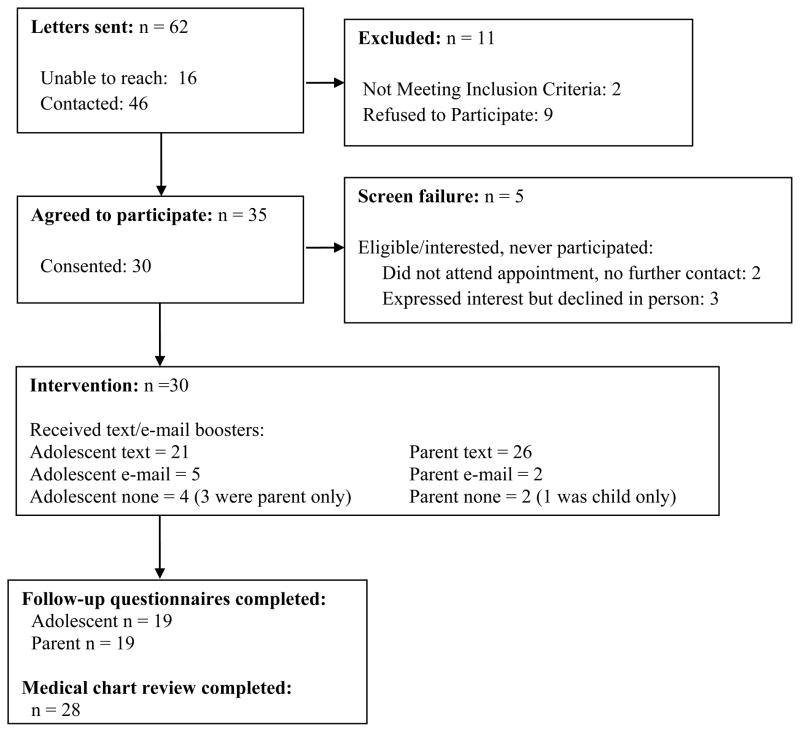

Sixty-two families were mailed recruitment letters describing study procedures; 16 were unable to be contacted (26%), 2 adolescents were ineligible due to a diagnosis of a developmental delay (3%), and 9 declined to participate (15%). Of the 35 adolescents who expressed interest in participating (80% of those reached and eligible), 30 adolescent/parent dyads completed consent procedures and were enrolled in the intervention (86%). Baseline data were available for all 30 participants. Follow-up medical data (HbA1c, mean daily BG monitoring frequency, mean daily BG level) were available for 28 participants, and follow-up questionnaire data were available for 19 participants (parent/adolescent dyad). See Figure 1. Families received a gift card for completion of baseline ($10) and follow-up ($10) assessments.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram for Checking In

Measures

Demographic data

Demographic variables, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, and family income level were assessed using a demographic questionnaire designed for study purposes.

Glycemic control

Medical variables such as insulin regimen, HbA1c, daily BG monitoring frequency, and mean BG level, were collected via medical chart review. Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c is the most widely accepted measure of average glucose level over the preceding 2–3 months; quarterly assessments are recommended by the ADA and routinely collected at each clinic visit.16 All assays are conducted with a DCA 2000+ analyzer--a point-of-care diabetes management platform that performs a HbA1c test in minutes.17 Glucometers were downloaded as part of routine clinical care and BG data were extracted from the clinic visits closest to baseline and follow-up to calculate the mean number of BG checks/day and the average daily BG level from the 30 days prior to baseline and follow-up data collection.

Diabetes management behaviors

Parents and adolescents completed the Self-Care Inventory (SCI), a measure that assesses how well youth have followed prescribed recommendations for 14 specific diabetes self-care behaviors over the past two weeks; higher scores indicate greater adherence to the diabetes care regimen.18 Good evidence of internal consistency for the adolescent report has been reported (α = .79).19 Internal consistency estimates in the current sample for the adolescent report (α = .73) and parent report (α = .80) were adequate.

Parental monitoring of diabetes tasks

Parents completed the Parental Monitoring of Diabetes Scale, a brief 18 item measure that assesses frequency of oversight of diabetes related behaviors, including monitoring of and communication about BG levels; higher scores indicate more parent monitoring.6 It has been used extensively with parents of adolescents with T1D and has strong psychometric properties.6,20 Internal consistency for this sample was adequate (α = .76).

Collaborative parent involvement

Adolescents completed the Collaborative Parent Involvement (CPI) scale, a 12 item self-report measure that assesses the frequency of parent involvement in diabetes related tasks;21 higher scores indicate greater parent involvement. The CPI has been associated with parent and adolescent reports of adherence and adolescent quality of life.21 Internal consistency for this sample was excellent (α = .91).

Diabetes-related conflict

Parents and adolescents completed the Diabetes Family Conflict Scale-Revised (DFCS), a 19 item scale that assesses conflict and disagreements related to diabetes care; higher scores indicate more conflict.22,23 The DFCS has strong psychometric properties. It was recently revised and re-validated for use with adolescents with type 1 diabetes and their parents.23 Internal consistency for this sample was excellent for both the adolescent report (α = .95) and the parent report (α = .94).

Satisfaction data

In order to obtain participant feedback regarding Checking In, parents and adolescents completed 13 questions, 5 of which were open ended, regarding their thoughts on the intervention. Examples include, “How often did you have the ‘3 Minute Meetings’?” and “Tell us about your experience with the Checking In intervention.” Participating physicians (n=2) completed a brief 15 minute interview with a study team member at the end of the intervention period to discuss their impressions of the intervention and potential areas of improvement.

Treatment fidelity

Approximately 25% of intervention sessions (n=7) were randomly selected for audio recording to evaluate intervention fidelity. Fidelity reviews were conducted by two research assistants not involved in intervention development and reviewed by the primary author to calculate fidelity to the intervention script.

Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (22nd edition). As this was a non-randomized pilot study with a short follow-up period, the goals of analyses were to assess the feasibility of program implementation, identify trends in intervention effects, and evaluate participant satisfaction. Intent-to-treat analyses were used when possible. Paired t tests were conducted to evaluate changes in key T1D indicators (n=28) and psychosocial measures (n=19) pre- and post-intervention. Satisfaction data were evaluated descriptively.

Results

Demographic Data

Thirty adolescent-parent dyads completed baseline data collection. Adolescents were between ages 11–15 (M age = 13.67 years ±1.20 years) and had been diagnosed with T1D for an average of 6.82 years (± 3.32 years). Mean glycemic control was 8.87% (74 mmol/mol), falling above the current American Diabetes Association recommended HbA1c level ≤ 7.5% (58 mmol/mol) for youth.24 See Table 1 for demographic details.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics at Baseline

| % | Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Age (years) | 13.67 | 1.20 | 11.13–15.93 | |

| Adolescent Sex (% female) | 46.67 | |||

| Adolescent Race (% Caucasian) | 66.67 | |||

| Parent Age (years) | 46.66 | 8.17 | 28.82–65.97 | |

| Parent Sex (% female) | 83.33 | |||

| Household Income (% > $100,000/year) | 61.50 | |||

| Duration of T1D (years) | 6.82 | 3.32 | 2.28–13.41 | |

| Regimen type (% intensive) | 73.33 | |||

| HbA1c (%) | 8.87% (74 mmol/mol) | 1.64 | 6.50%–14.00% (48–140 mmol/mol) |

Pre- to Post-Intervention

Although changes were in the expected direction for indicators of glycemic control, change from pre- to post-intervention for HbA1c, BG monitoring frequency, or mean BG level did not reach significance. There were no significant changes evidenced in adolescent- or parent-reported adherence, adolescent-reported parental involvement in T1D management, or parent-reported monitoring of diabetes related tasks. There was a trend for decreased parent-reported diabetes-related conflict from pre- to post-intervention (t(18)=2.11, p=0.05). See Table 2.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations Pre- and Post-Intervention Participation

| Pre- M (SD) | Post- M (SD) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycemic Indicators | |||

| HbA1c | 8.83 (1.69) | 8.61 (1.47) | .31 |

| Daily BG monitoring frequency | 4.07 (2.15) | 4.52 (2.50) | .10 |

| Daily BG level (mg/dL) | 216.28 (51.91) | 209.77 (56.29) | .31 |

| Adolescent- and Parent-Report Measures | |||

| Self-Care Inventory - Adolescent | 37.82 (5.75) | 39.02 (4.93) | .30 |

| Self-Care Inventory - Parent | 38.31 (5.56) | 37.96 (4.93) | .75 |

| Collaborative Parent Involvement - Adolescent | 37.55 (8.53) | 40.32 (8.97) | .26 |

| Parental Monitoring of Diabetes Scale - Parent | 73.11 (10.52) | 76.26 (7.26) | .20 |

| Diabetes Family Conflict Scale - Adolescent | 35.63 (18.41) | 35.79 (15.66) | .93 |

| Diabetes Family Conflict Scale - Parent | 33.74 (12.12) | 30.05 (10.08) | .05* |

Significant at p ≤ .05

Subgroup Analyses

Nineteen parents completed the follow-up questionnaires. Parent-report data collected about program participation revealed that 15/19 (79%) parent-adolescent dyads reported completing the 3MMs at least once/week for the duration of the 12 week intervention period; 4 parents reported completing the 3MMs fewer than once a week and 11 parents did not complete the follow-up questionnaires or provide data about 3MM completion. Participants who endorsed completing 3MMs fewer than once/week or did not complete follow-up questionnaire data collection demonstrated no significant changes from pre- to post-intervention in health outcome measures or parent- and adolescent-reported psychosocial measures (as available).

Participants who endorsed completing 3MMs once/week or more for the intervention period demonstrated significant changes from pre- to post-intervention in frequency of BG monitoring, with the average daily BG monitoring frequency increasing from 4.29 BG checks/day pre-intervention to 4.82 checks/day BG checks/day post-intervention (t(13) = −2.43, p<.05. While it did not reach significance, there was also a decrease in HbA1c evidenced for this group (pre-intervention HbA1c = 9.04 (74 mmol/mol) vs. post-intervention HbA1c = 8.47 (69 mmol/mol), t(14) = 1.91, p=.08). Similarly, there was a non-significant trend for adolescents reporting increased parental involvement for this group (pre-intervention CPI score = 35.90 vs. post-intervention CPI score = 40.60, t(14) = −1.95, p=.07).

Satisfaction Data

Nineteen parent/adolescent dyads completed the satisfaction questionnaires. As reported earlier, 15 parents reported completing 3MMs once/week or more frequently for the intervention period and 4 parents reported completing 3MMs fewer than once/week. Ten parents reported that the 3MMs were helpful in improving their child’s T1D management; parents specifically noted that the 3MMs were a helpful, positive reminder to communicate regularly about BG monitoring and make necessary changes. One parent reported, “When I was meeting with her so often, I think she began to get used to me asking questions so it became more of a conversation and less of an argument.” Parents who reported that the 3MMs were not helpful noted that they were not necessary because they already had good communication and/or consistent check-ins with their child (n=5), that they did not meet regularly (n=3), or that the regular meetings did not encourage their child to change his/her behavior (n=1). All parents (n=19) reported a desire to continue to hold 3MMs with their child. Twelve parents reported that the text messages were beneficial and 7 parents reported that they used information provided during the clinic visit to upload or update their child’s glucometer (e.g. change date/time). Thirteen parents provided specific positive comments about the overall Checking In program, including: “The program is very beneficial.”; “Hoping to continue these new habits and continue to keep the A1c under 8.”; “A great way to continue communication with my child as she becomes increasingly independent.”

Adolescents reported similar experiences with the Checking In program. Twelve adolescents reported that the 3MMs were helpful in improving their T1D care, noting: “Helped lower stress” and “It helped me to get a better A1c.” Participants who reported that the 3MMs were not helpful indicated that they did not hold regular 3MMs (n=4) or they already had good communication with parent(s) (n=2). Fourteen participants planned to continue 3MMs with their parent(s). Adolescents were less enthusiastic than parents about the text messages, with only 3 adolescents reporting a positive experience. Adolescents who disliked the text messages reported that the text reminders were “nagging,” “annoying,” or made them feel “guilty.” Six adolescents reported using the provided information to update or upload glucometers. Ten adolescents provided specific positive comments about the overall Checking In program, including: “I liked it; it was helpful to get my BGs in check.”; “I think it is very helpful…a stepping stone to talking more often to the point where you don’t need the meetings at all.”

Two physicians delivered the intervention for the 30 participants. Both reported high satisfaction with the Checking In program, particularly noting the intervention’s brevity, ease of implementation, alignment with clinical goals, and helpful print materials. Both also noted a desire to use the Checking In materials clinically with adolescents with T1D. Specific comments for future modification included delivering the intervention closer to diagnosis, focusing on early adolescence when the transition of responsibility begins (ages 10–12), and targeting adolescents in poor glycemic control. Both physicians also felt that the intervention needed to be reinforced more consistently with the family, potentially by offering more frequent medical follow-up and providing parents with enhanced strategies to address inadequate BG monitoring frequency.

Treatment Fidelity

A subset of interventions (n=7) were audiorecorded and reviewed by two independent coders for adherence to the intervention content. Physicians spent an average of 2 minutes, 54 seconds delivering intervention content (range = 45 seconds – 6 minutes, 45 seconds). One hundred percent of audiorecorded sessions included use of the language in the Checking In script, including “3 Minute Meetings” and the importance of parent-adolescent communication. All participants (100%) received the Checking In intervention printed handout. The physician clearly set a goal with the family related to 3MMs in 57% of sessions and encouraged parents to learn how to operate the adolescent’s meter in 57% of sessions.

Discussion

This study evaluates a very brief, inexpensive physician-delivered intervention targeting parent-adolescent communication about BG monitoring. While changes were in the expected direction, T1D behaviors did not significantly change from pre- to post-intervention with the exception of a trend related to decreased parent-reported conflict around diabetes management. When examining a subgroup of participants who reported adhering to the recommended intervention, post-intervention results found a significant increase in BG monitoring frequency and a clinical decrease in HbA1c (HbA1c change >0.5%). Parents and adolescents were largely satisfied with the intervention. It is likely that this brief intervention can be easily integrated into routine diabetes clinical care.

Half of the total sample reported implementing the 3MMs at least once/week, and results suggested that consistent implementation of the 3MM procedure may improve T1D health indicators. The purpose of the pilot was to explore trends in T1D indicators post-intervention and the sample’s size may have limited the ability to detect more significant results. The sample was not large enough to determine the participant characteristics associated with adherence to the intervention procedures. However, the improvements were seen irrespective of baseline HbA1c and a clinical decrease in HbA1c of 0.57% over a 3–4 month period is meaningful.

Regardless of parental consistency in implementing the Checking In Procedures, all parents felt that the Checking In content was important and planned to continue to meet with their child to routinely discuss BG monitoring results. Satisfaction data provides further insight into how to target the program, as some parents who already routinely communicated about BG values with their children did not see as much value in the structured format of the 3MMs. Adolescents were also generally happy with their participation in the program. This could be due, in part, to the fact there was a prearranged time and structure to discuss the potentially sensitive topic of BG monitoring, and adolescents had better time to prepare to discuss BG results with their parent. Future research could incorporate ecological momentary assessment to evaluate parent/adolescent mood and perceptions immediately before and after the 3MMs. The ability to video record or track 3MM content would also be valuable to better determine the time spent discussing BG values and any potential differences in the tone of the discussion.

Adolescents were less positive about the text message reminders than parents. Although some studies suggest that adolescents prefer mobile technology for health,14 most adolescents did not enjoy one-way text reminders about scheduling 3MMs. Adolescents may be more interested in engaging texts that require a response or provide interesting facts or quizzes about diabetes health.25 Results demonstrate that parents may enjoy opportunities to be more involved in T1D adherence reminders and may appreciate the opportunity to receive text message reminders related to diabetes care. Future interventions in this age group could tailor texts to parents and adolescents to better match their preferences for content.

Overall, this brief intervention was feasible to deliver in the clinic setting and promoted T1D care for a subset of engaged adolescents with T1D. Physicians reported high levels of satisfaction and, as the average delivery time of intervention content was under 3 minutes, it is likely that this intervention is sustainable and easily translatable to a busy clinic setting. Physicians appreciated having concrete strategies to provide to families and having physicians deliver the information likely increased enthusiasm for the program. It will be important to expand this trial to a larger, more representative sample of adolescents to see if results can be replicated. However, this intervention is significantly less intensive than other large funded clinic-based interventions,26,27 and preliminary results are promising.

There are some limitations to note related to the current trial. Specifically, this real-world intervention trial was an unfunded pilot and the enrolled sample was relatively small. Approximately one-third of participants did not complete psychosocial questionnaires at follow-up and resources were not available to track down non-responders to evaluate their experience with the program. Although most changes from pre- to post-intervention were in the expected direction, the study was not sufficiently powered to detect significant results. Future research could include a control group and a larger sample to better attribute changes to the Checking In intervention and evaluate which participants may benefit the most from exposure to Checking In. For example, physician participants felt that intervention delivery should be targeted to groups at increased risk, including newly diagnosed adolescents and those in poor glycemic control.

It is important to establish a foundation for good communication with parents early in adolescence and for communication and oversight of diabetes management to continue throughout adolescence. Checking In offers health care providers a brief, structured way to encourage consistent communication about T1D management and health. Parents and adolescents in this small but diverse sample were generally positive about the intervention, and the format is easily translatable to a busy clinic setting. Results of this low-cost physician-delivered intervention targeting parent-adolescent communication demonstrate feasibility as well as trends toward improvement in key T1D health indicators. Frequent review of BG meter data may be a useful strategy to improve health outcomes and parent-adolescent communication.

Acknowledgments

Financial assistance: This study was unfunded. Dr. Monaghan is funded by NIH/NIDDK K23DK099250.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Paul Kaplowitz, MD, PhD, Children’s National Health System.

References

- 1.Pettitt D, Talton J, Dabelea D, Divers J, Imperatore G, Lawrence J, Liese A, Linder B, Mayer-Davis E, Pihoker C, Saydah S, Standiford D, Hamman R for the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study Group. Prevalence of diabetes in U.S. youth in 2009: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(2):402–408. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schilling L, Knafl K, Grey M. Changing patterns of self-management in youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Nurs. 2006;21(6):412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helgeson V, Siminerio L, Escobar O, Becker D. Predictors of metabolic control among adolescents with diabetes: a 4-year longitudinal study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(3):254–270. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hood K, Peterson C, Rohan J, Drotar D. Association between adherence and glycemic control in pediatric type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Pediatr. 2009;124(6):e1171–e1179. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helgeson V, Honcharuk E, Becker D, Escobar O, Siminerio L. A focus on blood glucose monitoring: relation to glycemic control and determinants of frequency. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12(1):25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis D, Podolski C, Frey M, Naar-King S, Wang B, Moltz K. The role of parental monitoring in adolescent health outcomes: impact on regimen adherence in youth with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(8):907–917. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King P, Berg C, Butner J, Butler J, Wiebe D. Longitudinal trajectories of parental involvement in type 1 diabetes and adolescents’ adherence. Health Psychol. 2014;33(5):424–432. doi: 10.1037/a0032804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson B, Holmbeck G, Iannotti R, McKay S, Lochrie A, Volkening L, Laffel L. Dyadic measures of the parent–child relationship during the transition to adolescence and glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Fam Syst Health. 2009;27(2):141–152. doi: 10.1037/a0015759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll A, Downs S, Marrero D. What adolescents with type I diabetes and their parents want from testing technology: a qualitative study. Comput Inform Nur. 2007;25(1):23–29. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200701000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hood KK, Butler DA, Volkening LK, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM. The Blood Glucose Monitoring Communication questionnaire: an instrument to measure affect specific to blood glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care Nov. 2004;27(11):2610–2615. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll A, DiMeglio L, Stein S, Marrero D. Contracting and monitoring relationships for adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a pilot study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(5):543–549. doi: 10.1089/dia.2010.0181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croom A, Wiebe DJ, Berg CA, Lindsay R, Donaldson D, Foster C, Murray M, Swinyard MT. Adolescent and parent perceptions of patient-centered communication while managing type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol Mar. 2011;36(2):206–215. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford CA, Davenport AF, Meier A, McRee A-L. Partnerships between parents and health care professionals to improve adolescent health. J Adolesc Health. 2011;49(1):53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herbert LJ, Owen V, Pascarella L, Streisand R. Text message interventions for children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2013;15(5):362–370. doi: 10.1089/dia.2012.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverstein J, Klingensmith G, Copeland K, Plotnick LP, Kaufman F, Laffel L, Deeb L, Grey M, Anderson B, Holzmeister L, Clark N. Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(1):186–212. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diabetes Research in Children Network (DirecNet) Study G. Chase HP, Beck R, Tamborlane W, Buckingham B, Mauras N, Tsalikian E, Wysocki T, Weinzimer S, Kollman C, Ruedy K, Xing D. A randomized multicenter trial comparing the GlucoWatch Biographer with standard glucose monitoring in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1101–1106. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewin A, LaGreca A, Geffken G, Williams L, Duke D, Storch E, Silverstein J. Validity and reliability of an adolescent and parent rating scale of type 1 diabetes adherence behaviors: the Self-Care Inventory (SCI) J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(9):999–1007. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korbel CD, Wiebe DJ, Berg CA, Palmer DL. Gender differences in adherence to type 1 diabetes management across adolescence: the mediating role of depression. Child Health Care. 2007;36(1):83–98. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belendez M, de wit M, Snoek FJ. Assessment of parent-adolescent partnership in diabetes care: a review of measures. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(2):205–215. doi: 10.1177/0145721709359205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nansel TR, Rovner AJ, Haynie DL, Iannotti RJ, Simons-Morton B, Wysocki T, Anderson B, Weissberg-Benchell J, Laffel L. Development and validation of the collaborative parent involvement scale for youths with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(1):30–40. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin RR, Young-Hyman D, Peyrot M. Parent-child responsibility and conflict in diabetes care (Abstract) Diabetes. 1989;38:28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hood K, Butler D, Anderson B, Laffel L. Updated and revised Diabetes Family Conflict Scale. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(7):1764–1769. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiang JL, Kirkman MS, Laffel LMB, Peters AL. Type 1 diabetes through the life span: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(7):2034–2054. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herbert LJ, Mehta P, Monaghan M, Cogen F, Streisand R. Feasibility of the SMART Project: a text message program for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2014;27(4):265–269. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.27.4.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes C, Chen R, Mackey E, Grey M, Streisand R. Randomized clinical trial of clinic-integrated, low-intensity treatment to prevent deterioration of disease care in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(6):1535–1543. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz ML, Volkening LK, Butler DA, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM. Family-based psychoeducation and care ambassador intervention to improve glycemic control in youth with type 1 diabetes: a randomized trial. Pediatr Diabetes. 2014;15(2):142–150. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]