Abstract

Electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes (NO2-FA) are products of nitric oxide and nitrite-mediated unsaturated fatty acid nitration. These electrophilic products induce pleiotropic signaling actions that modulate metabolic and inflammatory responses in cell and animal models. The metabolism of NO2-FA includes reduction of the vinyl nitro moiety by prostaglandin reductase-1, mitochondrial β–oxidation and Michael addition with low molecular weight nucleophilic amino acids. Complex lipid reactions of fatty acid nitroalkenes are not well defined. Herein we report the detection and characterization of NO2-FA-containing triacylglycerides (NO2-FA-TAG) via mass spectrometry-based methods. In this regard, unsaturated fatty acids of dietary triacylglycerides are targets for nitration reactions during gastric acidification, where NO2-FA-TAG can be detected in rat plasma after oral administration of nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA). Furthermore, the characterization and profiling of these species, including the generation of beta oxidation and dehydrogenation products, could be detected in NO2-OA supplemented adipocytes. These data revealed that NO2-FA-TAG, formed by either the direct nitration of esterified unsaturated fatty acids or the incorporation of nitrated free fatty acids into triacylglycerides, contribute to the systemic distribution of these reactive electrophilic mediators and may serve as a depot for subsequent mobilization by lipases to in turn impact adipocyte homeostasis and tissue signaling events.

Supplementary key words: triglycerides, nitro fatty acids, conjugated linoleic acid, nitrite, nitrate, mass spectrometry, anti-inflammatory, nitro-oleic acid, adipocytes, nitroalkane

INTRODUCTION

Fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives (NO2-FA) are formed by the addition reaction of nitrogen dioxide (•NO2), a byproduct of reactions of nitric oxide (•NO) and nitrite (NO2−)-derived species, with unsaturated fatty acids (1). The electron withdrawing nitro group renders the β alkenyl carbon electron deficient with a partial positive charge and promotes reversible Michael addition reactions of electrophilic NO2-FA with cellular nucleophiles such as cysteine and histidine-containing peptides and proteins (2–4). These reactions can modulate the activity of functionally-significant proteins, especially during the conditions of metabolic stress and inflammation that promote fatty acid nitration. In particular, there is a significant impact on gene expression responses regulated by nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) and nuclear transcription factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Nrf2/Keap1) and the heat shock response-regulating heat shock factor-1, as well as the activity of ion channels such as the transient receptor potential cation channel sub-family V member 1 (TRPV1) (5–8).

The generation of NO2-FA is promoted by oxidative inflammatory responses and in the gastrointestinal tract, where acidic conditions promote the formation of nitrous acid (HNO2) and downstream nitration of unsaturated fatty acids (9–11). Fatty acid nitration has been predominantly studied using free fatty acids such as oleic acid (OA), conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) and arachidonic acid (12) because of challenges in the direct mass spectrometric analysis of complex lipids and nitroalkene instability during de-esterification reactions. This is a limitation, as dietary and endogenous free fatty acid levels are proportionately very low (1-5 % of total) when compared to the levels of esterified fatty acids in tissue compartments and foods. In adipose tissues, where NO2-FA exert critical signaling responses (13), and in foodstuffs the triacylglyceride (TAG) content is very high, suggesting that the unsaturated fatty acids in TAG could be both nitration targets and intermediates in nitroalkene-mediated signaling reactions in vivo. For example, exposure of the unsaturated fatty acid-rich TAG in extra virgin olive oil to nitrite and to the acidic conditions of digestion results in extensive fatty acid nitration (14). Gastric-induced fatty acid nitration mediates physiologically-relevant responses, as evidenced by the generation of NO2-FA products that in turn inhibit soluble epoxide hydrolase activity and downstream suppression of angiotensin II-induced hypertension in mice fed with CLA and NO2−, key precursors to NO2-FA generation (15).

The adipose tissue and liver are involved in dietary lipid trafficking, homeostasis and storage. Dysregulation of lipid handling and oxidation are hallmarks of several pathological conditions including atherosclerosis, obesity, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome (16–18). After a meal, TAG are hydrolyzed, then fatty acids are absorbed, re-esterified and packaged into chylomicrons that are processed by the liver and delivered as very low density lipoproteins (VLDL) to distal organs including white adipose tissue. Upon entry into adipocytes, free fatty acids derived from TAG participate in β–oxidation, reduction and elongation reactions and are re-esterified into TAG for storage. It is evident that >50% of this pool of esterified fatty acids is very active in TAG remodeling reactions on a daily basis (19, 20).

The detection and characterization of TAG typically involves separation by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) or liquid chromatography (LC), then hydrolysis and derivatization for analysis by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) (21). Recently, high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) has become a powerful tool for characterizing TAG in biological samples, facilitating the analysis of the large number of structural and positional isomers displayed by TAG. This strategy also avoids GC-induced thermal decomposition of TAG (22). TAG are commonly analyzed in positive ion mode as ammonium [M+NH4]+ or alkali metal [M+metal]+ adducts by electro spray ionization (ESI) or atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) methods (23, 24). In general, fragmentation of [M+NH4]+ yields three “diglyceride ions” [M-R1COOH-NH3]+, [M-R2COOH-NH3]+ and [M-R3COOH-NH3]+, that correspond to neutral losses of fatty acyl substituents as free carboxylic acid and ammonia from the sn-1, sn-2 and sn-3 positions of the glycerol backbone, respectively. These diglyceride product ions generate the corresponding acylium [RnCO]+ and monoglyceride [RnC=O+74]+ ions after MS3 fragmentation (25, 26). Structural information at this level is of relevance, as the position of the esterified fatty acyl substituents affects both lipid absorption and metabolism, and can modulate atherogenic events (27, 28). In this regard, the detection and characterization of NO2-FA-TAG, while not highly abundant, can mediate the regulation of adaptive cell signaling responses. Herein, we report the nitration of TAG under gastric conditions and the preferential incorporation of nitroalkanes over nitroalkenes into adipocyte and rat plasma TAG by directly measuring products both before and after hydrolysis using HPLC-mass spectrometry analysis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Chemicals were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma unless otherwise stated (St. Louis, MO). Artificial gastric fluid was from Fisher (Fisher Scientific International Inc., Hampton, NH). 1,3-dipalmitoylglycerol (1,3-DPG), oleic acid (OA) and conjugated-9,11-linoleic acid (CLA, cat. no. UC-60A) were from Nu-Check Prep, Inc. (Elysian, MN). Nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA) and NO2-[13C18]OA were synthesized as previously described (29). NO2-OA concentration was measured spectrophotometrically in methanol before each experiment (ε257 nm = 7000 M−1cm−1, (29)). The synthesis of nitro-stearic acid (NO2-18:0) was performed by selectively reducing the nitroalkene present in NO2-OA to a nitroalkane with sodium borohydride. NO2-[15N/D4]18:0 was obtained by reducing NO2-[15N/D4]18:1 in the same manner. The full structural characterization and synthetic procedures for generating this labeled standard will be separately reported. Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) and antibiotic- antimycotic solutions were from Corning Cellgro (Herndon, VA). Strata NH2 solid phase extraction (SPE) columns (55 μm, 70A) were from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA). Solvents used for extractions and mass spectrometric analyses were from Burdick and Jackson (Muskegon, MI).

Synthesis of dipalmitoyl-conjugated-linoleoyl-glycerol (CLA-TAG) standards

Two mixed triacyl precursors were generated by reaction of 1,2-dipalmitoylglycerol (1,2-DPG) and 1,3-DPG with CLA in the presence of N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) as coupling reagent. The 1,2-DPG and 1,3-DPG (50 mg) were dissolved in 10 ml dichloromethane, followed by 40 mg CLA. To the stirred flask, 34 mg DCC were added along with a few milligrams of 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) as catalyst. The flask was sealed under nitrogen and stirred at room temperature overnight. Then, the suspension was filtered to remove byproducts, the solids washed with dichloromethane and the solvents combined, evaporated and purified by column chromatography on silica gel (eluent: 0–5 % ethyl acetate/hexanes). The final yield (70 %) of 51 mg 1,2-dipalmitoyl-3-conjugated-linoleoyl-glycerol (3-CLA-TAG) and 41 mg (49 %) 1,3-dipalmitoyl-2-conjugated-linoleoyl-glycerol (2-CLA-TAG) were analyzed by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). 2-CLA-TAG and 3-CLA-TAG isomeric compositions were confirmed by MS/MS. Although 1,2-diacylglycerides are prone to rearrangement to 1,3-diacylglycerides (30), analysis of the product 3-CLA-TAG indicated that no acyl migration occurred (Supplementary Fig. 1).

In vitro nitration of 3-CLA-TAG and 2-CLA-TAG standards by gastric fluid

Synthetic nitrated triacylglyceride standards were generated by performing independent reactions of 100 μM 3-CLA-TAG or 2-CLA-TAG with 2 mM sodium nitrite (NaNO2) in artificial gastric fluid for 1 h at 37 °C, under continuous agitation. The lipid fraction was extracted by hexane, dried under a stream of nitrogen gas and dissolved in 0.2 ml ethyl acetate.

Cell culture

3T3-L1 fibroblasts were propagated and differentiated into adipocytes as previously (31). Fully differentiated adipocytes were then treated with 5 μM OA (n=3) or NO2-OA (n=5) in HBSS, to avoid Michael addition reaction with nucleophilic protein residues present in fetal bovine serum (FBS). Aliquots of media were obtained at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h, spiked with NO2-[13C18]OA internal standard, extracted using the Bligh and Dyer method (32), dried under a stream of nitrogen and reconstituted in 0.2 ml methanol for HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis. At the end of the treatment, adipocytes were rinsed with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS), scraped and lipids extracted.

Animal study

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (6-8 week old) were gavaged with NO2-OA (100 mg/kg) dissolved in sesame oil. Blood samples were obtained at different time points and plasma obtained by centrifugation. A sample volume of 200 μl of plasma was extracted. Plasma samples were provided by Complexa Inc. under a material transfer agreement #00000401.

Adipocyte and rat plasma lipid extraction

Adipocyte and rat plasma lipids were extracted according to Bligh and Dyer (32), dried under a stream of nitrogen and dissolved in 0.5 ml hexane/methyl tert-butyl ether/acetic acid (HBA, 100:3:0.3 v/v/v). Nitrated species were not detected in the OA-treated adipocytes (control) or untreated rat plasma. Adipocyte and rat plasma lipid classes were further resolved using SPE Strata NH2 columns 500 mg/6 ml and 100 mg/1 ml, respectively (33). Briefly, columns were washed twice with 2 ml acetone/water (7:1, v/v) and pre-conditioned twice with 2 ml hexane. The samples solubilized in HBA were loaded on the columns and cholesterol esters, TAG, mono-diglycerides and free fatty acids were sequentially eluted with 12 ml (for adipocyte lipids) or with 2 ml (for rat plasma lipids) of hexane, hexane/chloroform/ethyl acetate (100:5:5, v/v/v), chloroform/2-propanol (2:1, v/v) and diethyl ether/2 % acetic acid, respectively. The solvents were evaporated under a stream of nitrogen and TAG and free fatty acid fractions were dissolved in 0.2 ml ethyl acetate and methanol, respectively. Detection of NO2-FA-TAG was performed by HPLC-HR-MS/MS and HPLC-APCI-MS/MS while NO2-FA were analyzed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS.

Enzymatic hydrolysis of triacylglycerides

Lipid extracts containing adipocyte and rat plasma TAG were spiked with NO2-[13C18]OA and NO2-[15N/D4]18:0 internal standards respectively, dried and incubated in presence of 1 ml porcine pancreatic lipase (0.4 mg protein/ml) in 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and 10 μl sodium cholate (40 mg/ml), at 37 °C for 3 h under agitation. After hydrolysis, NO2-FA were extracted using the Bligh and Dyer method (32), dried under a stream of nitrogen and reconstituted in 0.2 ml methanol for HPLC-MS/MS analysis.

Chromatography

Analysis of NO2-FA was performed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS using an analytical C18 Luna column (2 × 100 mm, 5 μm, Phenomenex) at a 0.6 ml/min flow rate, with a gradient solvent system consisting of water containing 0.1 % acetic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile containing 0.1 % acetic acid (solvent B). Samples were chromatographically resolved using the following gradient program: 45-100 % solvent B (0-8 min); 100 % solvent B (8-10 min) followed by 2 min re-equilibration to initial conditions.

Analysis of NO2-FA-TAG was performed by HPLC-HR-MS/MS and HPLC-APCI-MS/MS using a C18 Luna column (2 x 150 mm, 3 μm, Phenomenex) at a flow rate of 0.45 ml/min. The gradient solvent system consisted of acetonitrile (solvent A) and ethyl acetate (solvent B), in presence of 66 μM ammonium acetate to generate [M+NH4]+ species (34). NO2-FA-TAG were eluted over 28 min using the following gradient: 0-30 % solvent B (0-3 min); 30-65 % solvent B (3-24 min); 65-90 % solvent B (24-26 min); 90 % solvent B (26-28 min) to then re-equilibrate to initial conditions for an additional 2 min.

Mass spectrometry

NO2-FA were analyzed by HPLC-MS/MS using an API4000 Q-trap triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, San Jose, CA) equipped with an electrospray ionization source (ESI) in negative mode. The following parameters were used: declustering potential (DP) –75 V, collision energy (CE) –35 eV and a desolvation temperature of 650 °C. The following multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions were used for the different NO2-FA metabolites: nitro-stearic acid (NO2-18:0, 328.3/46), nitro-oleic acid (NO2-OA, NO2-18:1, 326.3/46), nitro-hexadecanoic acid (NO2-16:0, 300.3/46), nitro-hexadecenoic acid (NO2-16:1, 298.3/46), nitro-tetradecanoic acid (NO2-14:0, 272.3/46), nitro-tetradecenoic acid (NO2-14:1, 270.3/46) and nitro-dodecanoic acid (NO2-12:0, 244.3/46) (35). Elongation products of NO2-OA, β-oxidation products shorter than C12 and nitro-dodecenoic acid (NO2-12:1) were not detected. Relative concentrations of NO2-FA in cell media over 24 h were reported as area ratio NO2-FA/NO2-[13C18]OA and relative concentrations of NO2-FA at 24 h in cell media and extracts (free fatty acid fraction and lipase hydrolyzed TAG fraction) were reported as an area ratio of NO2-FA/NO2-OA. Quantification of non-electrophilic NO2-FA in rat plasma was performed by stable isotopic dilution analysis using NO2-18:0 calibration curves in the presence of the NO2-[15N/D4]18:0 internal standard (MRM 333.3/47).

Structural and positional analysis of adipocyte NO2-FA-TAG was performed by HPLC-HR-MS/MS using an LTQ Velos Orbitrap (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a HESI II electrospray source, in positive ion mode. The following parameters were used: source temperature 250 °C, capillary temperature 300 °C, sheath gas flow 9, auxiliary gas flow 5, sweep gas flow 2, source voltage 5 kV, S-lens RF level 70 %. Full mass scan experiments were carried out from 700 to 1000 m/z at a resolving power of 7500 full width at half maximum (FWHM). Ions with odd mass numbers, corresponding to potential NO2-FA-TAG, were selected and subjected to data dependent MS2 and MS3 fragmentations. The instrument FT-mode was calibrated using the manufacturer’s recommended calibration solution.

Analysis of NO2-FA-TAG in rat plasma was performed by HPLC-APCI-MS/MS using an API4000 Q-trap triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, San Jose, CA) equipped with an atmospheric pressure chemical ionization source (APCI) in positive mode. The following parameters were used: declustering potential (DP) 85 V, collision energy (CE) 35 eV, desolvation temperature 300°C and a nebulized current of 5 μA.

Statistical analysis

A Pearson’s product correlation was used to determine an association between intra and extracellular content of NO2-FA in adipocytes supplemented with NO2-OA. Values are expressed as means ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Mass spectrometry characterization of NO2-CLA-TAG generated under gastric conditions

The acidic gastric compartment is a physiological catalyst for NO2− mediated nitration and nitrosation reactions subsequent to the protonation of NO2− to nitrous acid (HNO2) (pKa 3.4) and the secondary formation of dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3) and its products (9). To test if CLA-containing-TAG is a substrate for acidic nitration, 3-CLA-TAG and 2-CLA-TAG standards were incubated in artificial gastric fluid in the presence of 2 mM NaNO2. Several nitrated products were generated, including: NO2-CLA-TAG (m/z 893.7), NO2-oxo-OA-TAG (m/z 909.7), NO2-OH-OA-TAG (m/z 911.7) and NO2-OOH-OA-TAG (m/z 927.7) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The presence of oxygen during reactions suppresses the yield of NO2-CLA and promotes the formation of oxygenated NO2-CLA products (9). However, the gastric compartment, low in oxygen when compared to air-equilibrated experimental conditions, will favor the generation of products that are just nitrated rather than both oxidized and nitrated species in vitro. Since NO2-CLA is the principal nitrated free fatty acid derivative detected in human plasma and urine (36), focus in the present study was placed on further characterization of the ion m/z 893.7. This species displayed two peaks having HPLC retention times of 14.2 and 14.5 min (Fig. 1A) that were consistent with NO2-CLA-TAG (confirmed at the 1 ppm level) (inset in Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Detection and characterization of NO2-CLA-TAG generation by in vitro gastric conditions.

(A) Mass chromatogram of NO2-CLA-TAG as ammonium adduct (m/z 893.7) [M+NH4]+ and inset with its atomic composition and isotopic abundance. (B) MS2 spectral data of NO2-CLA-TAG. (C) MS3 spectral data of the MS2 even fragments m/z 620.4 [M-16:0-NH3]+. (D) MS3 spectral data of the MS2 odd fragment m/z 551.5 [M-NO2-CLA-NH3]+. Representative chemical structures are only shown for the 9-NO2-CLA-TAG isomer and corresponding product ions.

The NO2-CLA-TAG species were further structurally characterized via MS2 and MS3 fragmentation. MS2 analysis generated three “diglyceride ions”: two characteristic even mass-containing ions m/z 620.48 (containing one nitrogen) and one odd mass-containing ion m/z 551.50 (containing no nitrogen atoms) which corresponded to the neutral losses of the palmitoyl- and nitro-conjugated-linoleoyl free fatty acids and ammonia, respectively (Fig. 1B). The relative intensity of the product enabled the determination of positional isomers, since the loss of fatty acyl substituents from sn-1/sn-3 positions is energetically favored over losses at the sn-2 position (24, 37–39). Based on this observation, the nitro-conjugated-linoleoyl- substituent was assumed to be in the sn-2 position of the glycerol backbone, as the odd ion m/z 551.5 [M-NO2-CLA-NH3]+ was about 4-times less abundant than the even ions m/z 620.4 [M-16:0-NH3]+.

MS3 analysis on the diglyceride product ions provided further structural information. Collision induced dissociation (CID) fragmentation of m/z 620.4 gave two characteristic ions m/z 480.3 and m/z 493.3, generated by neutral losses of 140.2 amu and 127.2 amu respectively (Fig. 1C). These product ions correspond to the specific neutral losses characteristic of nitroalkene carbon chain fragmentation of 9-NO2-CLA and 12-NO2-CLA respectively (Fig. 1A) (9). Further fragmentation analysis of product ion m/z 620.4, showed formation of monoglyceride and acylium ions, such as [(NO2-CLA)C=O+74]+ (m/z 382.25), [(NO2-CLA)CO]+ (m/z 308.22), [(16:0)C=O+74]+ (m/z 313.27), and their corresponding dehydration products (m/z 602.4, m/z 364.2, m/z 290.2 and m/z 295.2) (Fig. 1C). The MS3 analysis of the fragment m/z 551.5 gave the expected product ion m/z 239.3 [(16:0)CO]+, confirming the presence of palmitoyl-substituents in sn-1 and sn-3 positions of the glycerol backbone (Fig. 1D).

NO2-OA metabolism, distribution and incorporation into TAG in adipocytes

The differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells to mature adipocytes provides a platform to model primary adipocyte lipid metabolism and the distribution and incorporation of NO2-OA into TAG (40). The analysis of NO2-OA added to the culture medium of adipocytes over 24 h showed that cellular NO2-18:1 was rapidly metabolized within the first two hours by β-oxidation reactions, yielding NO2-16:1 and NO2-14:1 (Fig. 2A–C). A second phase of metabolism was evident from 8 to 24 h, where the reduction of the nitroalkene to non-electrophilic nitroalkanes NO2-18:0, NO2-16:0, NO2-14:0 and NO2-12:0, with NO2-18:0 being the most abundant as evidenced by its relative area ratio (Fig. 2A–D). Of note, a mass balance study of metabolites was not performed, limiting the analysis of the data shown in Fig. 2 to comparisons of the relative levels obtained for each species at the different time points.

Fig. 2. Time-dependent changes in extracellular NO2-FA after supplementation of NO2-OA in adipocytes.

Values of electrophilic nitroalkenes (filled square) and non-electrophilic nitroalkanes (open square) are given as area ratio of (A) nitro- C18-, (B) C16-, (C) C14- and (D) C12- fatty acid/NO2-[13C18]OA over a period of 24 h. Data shown are the means ± SD of 3 independent experiments with 5 and 3 replicates each for NO2-OA and OA treatment, respectively.

To evaluate the cell distribution of NO2-FA metabolites, their incorporation into TAG, the intracellular (cell lysate), extracellular (cell media) and TAG esterified fractions (lipase-hydrolyzed TAG species) were analyzed. Nitroalkane metabolites were preferentially esterified as opposed to nitroalkene species, as evidenced by the higher area ratios of the various NO2-FA ions to NO2-OA (Fig. 3A–C). Nonetheless, NO2-OA was also esterified in the TAG fraction of adipocytes (Fig. 3A). Intracellular nitroalkanes had a higher area ratio than nitroalkanes detected extracellularly (Fig. 3B,C). This is most likely due to the Michael addition of electrophilic nitroalkenes with intracellular nucleophiles (e.g., glutathione, protein cysteine- and histidine-residues) and the relative concentrations of these species in these two compartments (35, 41). Overall, the relationship between intracellular and extracellular NO2-FA area ratio was strongly correlated (r2=0.98, P<0.001, Fig. 3D) with a preferential intracellular distribution of short and saturated chain length nitroalkane metabolites. In contrast, TAG-esterified species and intracellular NO2-FA area ratios were not strongly correlated, rather there was a significant esterification of longer chain nitroalkanes (e.g., NO2-16:0 and NO2-18:0) into TAG (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3. Metabolism, distribution and esterification of NO2-FA into TAG in adipocytes supplemented with NO2-OA.

Lipase-hydrolyzed TAG, cell lysate and cell media were analyzed by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS in negative mode to determine (A) esterified into TAG, (B) intracellular and (C) extracellular content of NO2-FA at 24 h, respectively. A strong correlation (r2 = 0.98, P < 0.001) was observed between (D) intracellular and extracellular but not between (E) esterified into TAG and intracellular content of NO2-FA. Values are given as area ratio of NO2-FA/NO2-OA. Data shown are the means ± SD of 3 independent experiments with 5 and 3 replicates each for NO2-OA and OA treatment, respectively.

Mass spectrometry analysis NO2-FA-TAG in adipocytes

The detection of NO2-FA after hydrolysis of adipocyte TAG motivated the direct detection and characterization of NO2-FA-TAG. Purified TAG fractions from cultured adipocytes were subjected to HPLC-HR-MS analysis in positive mode and the most intense odd mass ions were selected for MS2 fragmentation to identify NO2-FA-TAG and discriminate structural and positional isomers. Candidate ions of TAG containing a nitro group were selected based on confirmation of atomic composition using high resolution mass spectrometry at the 2 ppm level. Fragmentation of these ions generated even and odd “diglyceride ions” that allowed the identification of the fatty acyl chains present in the NO2-FA-TAG. Furthermore, the presence of an odd mass diacyl product ion, generated by the neutral loss of the nitro-fatty acyl substituent as free carboxylic acid and ammonia, allowed the identification of even mass fragments and confirmation of NO2-FA-TAG fatty acyl substituents and structure. This was further validated using a synthetic NO2-CLA-TAG standard. As an example, an ion with an m/z 893.7 and molecular composition in agreement with a NO2-FA-TAG (confirmed at the 1 ppm level, inset in Fig. 4A), presented two chromatographic peaks eluting at 12.5 and 13.2 min (Fig. 4A). MS2 analysis of the first and second peak unequivocally confirmed the presence of non-electrophilic NO2-FA-TAG isomers 16:1/NO2-18:0/16:1-TAG and NO2-16:0/16:1/18:1-TAG, respectively (Fig. 4A–C). The fragmentation of the first peak generated two abundant even mass products ions with m/z 622.5 [M-16:1-NH3]+ and one odd fragment with m/z 547.4 [M-NO2-18:0-NH3]+. These correspond to the neutral losses of palmitoleoyl- and nitro-stearoyl-substituents as free carboxylic acid and ammonia in sn-1/sn-3 and sn-2 positions of the glycerol backbone, respectively (Fig. 4B). The MS2 analysis of the second peak generated two even product ions m/z 622.5 [M-16:1-NH3]+, m/z 594.4 [M-18:1-NH3]+, and one odd ion at m/z 575.5 [M-NO2-16:0-NH3]+, stemming from the neutral loss of palmitoleoyl-, oleoyl- and nitro-palmitoyl- substituents as free carboxylic acid and ammonia from the glycerol backbone, respectively (Fig. 4C). In this case, the presence of a chromatographically co-eluting NO2-FA-TAG isomer (NO2-16:0/17:1/17:1-TAG), sharing the isobaric product ion m/z 575.5, did not allow a specific positional isomers discrimination (42).

Fig. 4. Mass spectrometry analysis of adipocyte NO2-FA-TAG.

Purified TAG fractions from adipocytes treated with 5 μM NO2-OA for 24 h were subjected to HPLC-HR-MS analysis in positive mode. (A) Mass chromatogram of NO2-FA-TAG as ammonium adducts (m/z 893.7) [M+NH4]+, inset with atomic composition and isotopic abundance. (B) MS2 spectral data of peak 1 in Fig. 4A. (C) MS2 spectral data of peak 2 in Fig. 4A. (D) MS3 spectral data of the MS2 even fragments m/z 622.5 [M-16:1-NH3]+ in Fig. 4B. (E) MS3 spectral data of the MS2 odd fragment m/z 547.4 [M-NO2-18:0-NH3]+ in Fig. 4B. a Order of notation does not connote regiochemistry. * Presence of a shared MS2 fragment from a co-eluting NO2-FA-TAG isomer (NO2-16:0/17:1/17:1-TAG).

To gain structural insight into non-electrophilic (nitroalkane) NO2-FA-TAG species, MS3 analysis of product ions was performed (Fig. 4D). Fragmentation of the even mass “diglyceride ions” with m/z 622.5 confirmed loss of water, generating the ion m/z 604.5, and monoglyceride and acylium ions [(NO2-18:0)C=O+74]+, [(NO2-18:0)CO]+ and [(16:1)C=O+74]+. In addition, the nitro-containing species [(NO2-18:0)C=O+74]+ and [(NO2-18:0)CO]+ also displayed loss of water, generating the ions m/z 368.2 and m/z 294.2, respectively. Interestingly, three new fragments m/z 591.4, m/z 573.4 and m/z 339.2 were identified. The first and the second ions were generated from a 31 amu mass loss (HNO) of the product ion m/z 622.5 and m/z 604.4 respectively, while m/z 339.2 originated from a 47 amu mass loss (HNO2) of the parent fragment ion [(NO2-18:0)C=O+74]+. MS3 analysis of the odd “diglyceride ion” m/z 547.4 showed the expected formation of [(16:1)C=O+74]+ and [(16:1)CO]+, confirming the presence of palmitoleyl-substituents in sn-1 and sn-3 positions of the glycerol backbone (Fig. 4E). This workflow was applied to characterize the predominant nitrated TAG detectable in adipocytes (Table 1). The analysis of positional isomers, on the basis of the relative intensities of the “diglyceride ions”, showed that nitroalkanes were preferentially incorporated into the sn-2 position of TAG. Accurate mass determination at the 2 ppm level for MS and MS2 analysis confirmed the molecular and fatty acid composition of these species, respectively. Overall, non-electrophilic medium to long chain NO2-FA metabolites (nitroalkane species) were TAG-esterified, nitroalkene-containing-TAG were not detectable and there was an absence of nitro-fatty acyl chains longer than C18 and shorter than C12 (Supplementary Table 1). NO2-FA incorporated into TAG were mostly saturated, in conjunction with saturated and monounsaturated C15-C17 (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1. Positional analysis of the most abundant non-electrophilic NO2-FA-TAG in adipocytes supplemented with NO2-OA.

Positional fatty acid distribution, specific product ion, accurate mass determination and retention time of non-electrophilic NO2-FA-TAG in positive ion mode.

| [NO2-FA-TAG + NH4]+

|

Diaglyceride product ion [M-RnCOOH-NH3]+ | Chemical formula | Experimental mass | Theoretical mass | Retention time (min) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sn-2 | sn-1/3 | ||||||

| NO2-18:0a | 16:0 | 16:1 | C53H103N2O8+ | 895.771 | 895.7709 | 14 | |

| NO2-18:0/16:0 | C37H70NO6+ | 624.5191 | 624.5198 | ||||

| NO2-18:0/16:1 | C37H68NO6+ | 622.5041 | 622.5041 | ||||

| 16:0/16:1 | C35H65O4+ | 549.4872 | 549.4877 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| NO2-18:0a | 16:1 | 15:0 | C52H101N2O8+ | 881.7538 | 881.7552 | 13.1 | |

| NO2-18:0/16:1 | C37H68NO6+ | 622.5037 | 622.5041 | ||||

| NO2-18:0/15:0 | C36H68NO6+ | 610.5045 | 610.5041 | ||||

| 16:1/15:0 | C34H63O4+ | 535.472 | 535.4721 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| NO2-18:0 | 16:1 | 16:1 | C53H101N2O8+ | 893.7561 | 893.7552 | 12.5 | |

| NO2-18:0/16:1 | C37H68NO6+ | 622.5036 | 622.5041 | ||||

| 16:1/16:1 | C35H63O4+ | 547.4714 | 547.4721 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| NO2-16:0 | 16:1 | 16:1 | C51H97N2O8+ | 865.7244 | 865.7239 | 11.5 | |

| NO2-16:0/16:1 | C35H64NO6+ | 594.472 | 594.4728 | ||||

| 16:1/16:1 | C35H63O4+ | 547.4711 | 547.4721 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| NO2-14:0 | 16:1 | 16:1 | C49H93N2O8+ | 837.6939 | 837.6926 | 10.9 | |

| NO2-14:0/16:1 | C33H60NO6+ | 566.4405 | 566.4415 | ||||

| 16:1/16:1 | C35H63O4+ | 547.4715 | 547.4721 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| NO2-14:0 | 18:1 | 16:1 | C51H97N2O8+ | 865.7254 | 865.7239 | 12.3 | |

| NO2-14:0/18:1 | C35H64NO6+ | 594.4722 | 594.4728 | ||||

| NO2-14:0/16:1 | C33H60NO6+ | 566.4406 | 566.4415 | ||||

| 16:1/18:1 | C37H67O4+ | 575.5033 | 575.5034 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| NO2-12:0 | 18:1 | 16:1 | C49H93N2O8+ | 837.6944 | 837.6926 | 11.7 | |

| NO2-12:0/18:1 | C33H60NO6+ | 566.4405 | 566.4415 | ||||

| NO2-12:0/16:1 | C31H56NO6+ | 538.4093 | 538.4102 | ||||

| 16:1/18:1 | C37H67O4+ | 575.5031 | 575.5034 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| NO2-12:0a | 16:0 | 16:1 | C47H91N2O8+ | 811.6784 | 811.677 | 11.8 | |

| NO2-12:0/16:0 | C31H58NO6+ | 540.4253 | 540.4259 | ||||

| NO2-12:0/16:1 | C31H56NO6+ | 538.4092 | 538.4102 | ||||

| 16:0/16:1 | C35H65O4+ | 549.4871 | 549.4877 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| NO2-12:0 | 16:1 | 16:1 | C47H89N2O8+ | 809.6611 | 809.6613 | 10.3 | |

| NO2-12:0/16:1 | C31H56NO6+ | 538.4094 | 538.4102 | ||||

| 16:1/16:1 | C35H63O4+ | 547.4712 | 547.4721 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| NO2-12:0 | 16:1 | 14:1 | C45H85N2O8+ | 781.6311 | 781.63 | 9 | |

| NO2-12:0/16:1 | C31H56NO6+ | 538.4095 | 538.4102 | ||||

| NO2-12:0/14:1 | C29H52NO6+ | 510.3786 | 510.3789 | ||||

| 14:1/16:1 | C33H59O4+ | 519.4402 | 519.4408 | ||||

Order of notation does not connote regiochemistry.

Analysis of NO2-FA-TAG in rat plasma

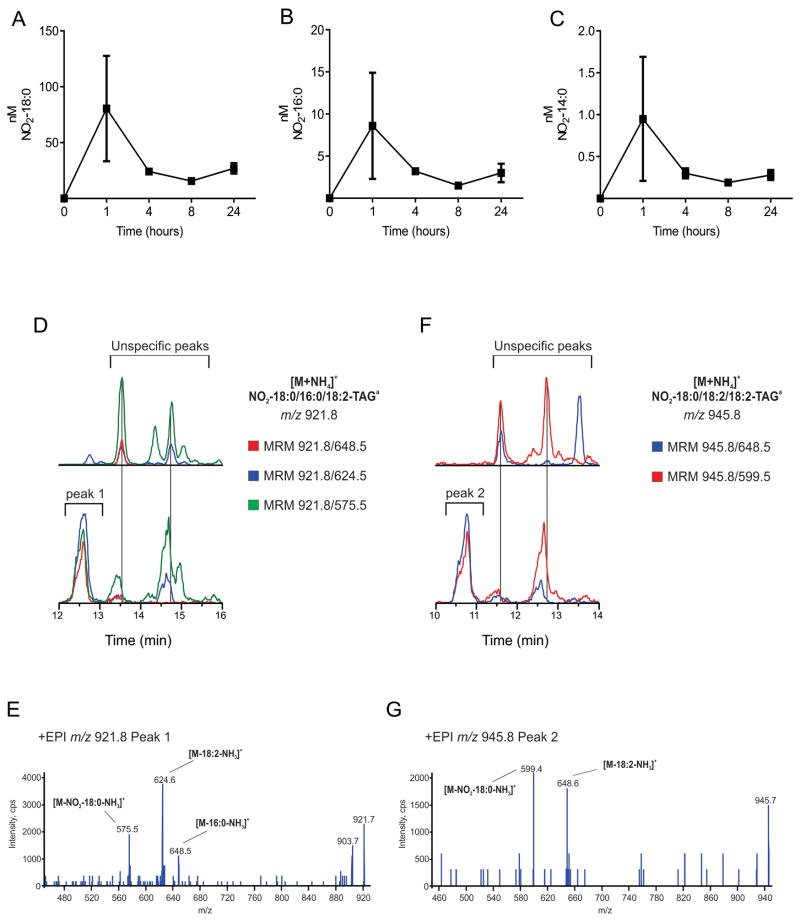

The detection of NO2-FA-TAG in adipocytes motivated the in vivo detection and characterization of TAG-adducted species in rat plasma after a single oral dose of the nitroalkene NO2-OA. Lipase hydrolysis of TAG-containing fractions from rat plasma, obtained at different time points after administration, showed the presence of non-electrophilic nitroalkanes NO2-18:0, NO2-16:0 and NO2-14:0 confirming the preferential and rapid incorporation of these reduced species in TAG (Fig. 5A–C). NO2-18:0 was the most abundant nitroalkane and displayed a concentration in the range of 16-113 nM (Fig. 5A). This result encouraged the detection of individual NO2-18:0-TAG species in rat plasma. As an initial approach, MRM screening for transitions for potential NO2-18:0-TAG was performed following the neutral loss of 346 amu (NO2-18:0+NH3), as NO2-18:0 was the most prominent non-electrophilic NO2-FA detected in plasma after lipase reaction.

Fig. 5. Characterization of rat plasma NO2-FA-TAG.

Kinetic analysis of (A) nitro- C18-, (B) C16-, (C) C14- fatty acid concentration (nM) in lipase hydrolyzed rat plasma triacylglycerides after supplementation of NO2-OA. (D, F) MRM chromatograms for NO2-18:0/16:0/18:2-TAG and NO2-18:0/18:2/18:2-TAG, as ammonium adducts in positive mode, in (upper panel) untreated and (lower panel) treated rat plasma samples. (E) EPI analysis of peak 1 for m/z 921.8. (G) EPI analysis of peak 2 for m/z 945.8. Data shown are the means ± SD of a pharmakinetic study performed on two treated and one control animal. a Order of notation does not connote regiochemistry.

Two candidate ions indicative of NO2-18:0-containing TAG were observed by evaluating the co-eluting MRM transitions (MRM 921.8/648.5, 921.8/624.5, 921.8/575.5 and 945.8/648.5, 945.8/599.5). These two species, with peaks at 12.6 min (peak 1 in Fig. 5D lower panel) and 10.7 min (peak 2 in Fig. 5F lower panel) were only present in NO2-OA gavaged plasma samples and were not detected in untreated samples (Fig. 5D,F upper panels). Structural confirmation of NO2-18:0/16:0/18:2-TAG and NO2-18:0/18:2/18:2-TAG was obtained by full scan MS/MS analysis of ions displaying m/z 921.8 and m/z 945.8 respectively (Fig. 5E,G). The fragmentation of m/z 921.8 generated two even mass products ions with m/z 648.5 [M-16:0-NH3]+, m/z 624.5 [M-18:2-NH3]+ and one odd fragment with m/z 575.5 [M-NO2-18:0-NH3]+. These correspond to the neutral losses of ammonia and acyl chains (palmitoyl-, linoleoyl- and nitro-stearoyl- respectively) from the glycerol backbone (Fig. 5E). Fragmentation of m/z 945.8 generated two even mass products ions with m/z 648.5 [M-18:2-NH3]+ and one odd fragment with m/z 599.5 [M-NO2-18:0-NH3]+ corresponding to the neutral losses of linoleoyl- and nitro-stearoyl- substituents as free carboxylic acid and ammonia from the glycerol backbone, respectively (Fig. 5G).

DISCUSSION

Enzymatic and non-enzymatic fatty acid oxidation reactions generate a wide array of products, some of which can act as signaling mediators rather than as pathogenic byproducts of inflammation. In addition to the oxidation of the free fatty acids, many oxidized fatty acid species are also found esterified in polar and neutral complex lipids. This includes esterified isoprostanes, hydroxyl fatty acid derivatives and lipid oxidation chain scission products such as 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) (43–45). In many instances, it is not well defined if oxidative fatty acid modifications occurred directly with esterified species or if a modified free fatty acid is subsequently esterified into a complex lipid following metabolic or inflammatory reactions.

NO2-FA, formed by oxidative inflammatory reactions and in the acidic gastric compartment (9), are pleiotropic signaling mediators that induce reversible post-translational protein modifications via reversible Michael addition reactions (2). Recent data also support that NO2-FA can be formed during digestion. For example, the exposure of extra virgin olive oil to NO2− under acidic conditions, followed by pancreatic lipase hydrolysis, resulted in significant extents of NO2-FA generation (14). This also suggested that unsaturated fatty acid-containing-TAG could be substrates for nitration. Dietary TAG, a key source of fatty acids, can undergo multiple cycles of hydrolysis and re-esterification. Lipases hydrolyze TAG in the lumen of the duodenum to permit free fatty acids to be absorbed, re-esterified in the liver and delivered to remote tissues by lipoproteins. Tissue uptake by adipocytes involves hydrolysis, internalization, and further esterification into TAG. Re-esterification requires the formation of coenzyme A (CoA) derivatives, central for directing mitochondrial fatty acid transport and supporting β-oxidation and acylation reactions. These events motivated the synthesis and characterization of a NO2-CLA-TAG and the present study of the uptake and metabolism of NO2-FA, as free and as complex lipid esterified-NO2-FA, in adipocytes and rat plasma. This is of relevance, since the formation of NO2-FA by gastric nitration of dietary lipids could represent a key source of NO2-FA-TAG that in turn could represent a pool of metabolic and inflammatory signaling mediators.

Vegetable oils and dairy products are rich in unsaturated fatty acid-containing TAG containing both essential and non-essential fatty acids (46, 47). Moreover, leafy vegetables, fruits and cured meat are excellent sources of NO2− and nitrate (NO3−) (48), which can be reduced to NO2− via entero-salivary anaerobic bacteria (49, 50). In the gastric compartment, the low pH induces protonation of NO2−, the generation of nitrogen dioxide (•NO2) (11, 51, 52) and the subsequent nitration of unsaturated fatty acids (10). This is confirmed by the nitration of both synthetic 3-CLA-TAG and 2-CLA-TAG standards exposed to in vitro gastric conditions in presence of NO2− (Fig. 1). The resultant NO2-CLA-TAG products share the same general MS2 fragmentation patterns as TAG, displaying the characteristic neutral losses of the fatty acyl chains and ammonia from sn-1, sn-2 and sn-3 positions. The application of the nitrogen rule allows for rapid screening of NO2-containing-products, as their ammonium adducts display odd mass values compared to even m/z values for [TAG+NH4]+. In addition, [TAG+NH4]+ fragmentation generates three odd “diglyceride ions” as previously reported (25), while NO2-CLA-TAG results in two even and one odd “diglyceride ion” products. The odd diacyl product ion, after CID fragmentation, reflects the neutral loss of a NO2-containing-fatty acyl chain.

The differentiation and characterization of the alternative positional isomers of NO2-CLA-TAG (acyl chain and nitro group positions) is of biochemical and biological relevance, as this will reflect fatty acyl substrates, shed light on the reaction mechanisms and can impact downstream cell signaling reactions. Of note, 1H NMR analysis of 3-CLA-TAG and 2-CLA-TAG resulted in identical spectra and did not allow for positional isomers evaluation (Supplemental Fig. 1A,C). In contrast, MS2 fragmentation of 3-CLA-TAG and 2-CLA-TAG standards permitted the determination of positional isomers by the relative abundance of diacyl product ions (24, 38), as neutral losses of sn-1 and sn-3 acyl chains are energetically favored over sn-2 fatty acyl chain (37, 39). Herein, the synthesis of 3-CLA-TAG and 2-CLA-TAG gave products with CLA esterified to the sn-1/3 positions (Supplementary Fig. 1B) and sn-2 position (Supplementary Fig. 1D), respectively. Nonetheless, MS2 analysis of NO2-CLA-TAG products displayed the same spectra suggesting acyl migration of NO2-CLA substituents to the sn-2 position during acidic nitration reactions (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1E). It is also possible that the presence of the nitro group induced changes in fragmentation efficiencies, disfavoring neutral loss of NO2-CLA+NH3.

A key mechanism for the metabolism of NO2-FA is reduction of the vinyl nitro substituent by prostaglandin reductase 1, yielding nitroalkane species lacking electrophilic reactivity and the capability to post-translationally modify the activity of critical transcriptional regulatory protein and enzyme targets (53, 54). Mass spectrometric characterization via MS3 analysis of NO2-CLA-TAG identified the nitro-conjugated linoleoyl- substituent. In addition to the commonly-observed acylium [RnCO]+ and [RnC=O+74]+ ions (26), MS3 analysis of the even diacyl product ions of NO2-CLA-TAG generated two characteristic nitrosamine and aldehyde ions that confirmed the presence of two positional isomers, the 9-NO2-CLA-TAG and 12-NO2-CLA-TAG respectively. This data is in agreement with fragmentation pathways previously reported for [9-NO2-CLA+Li]+ and [12-NO2-CLA+Li]+ (9). While NO2-CLA-TAG did not generate product ions stemming from HNO2 neutral losses typical for nitro-containing fatty acids (Fig. 1C) (9, 55), the fragmentation of the non-electrophilic NO2-18:0-TAG displayed this typical neutral loss (Fig. 4D). Moreover, MS3 analysis of NO2-18:0-TAG revealed a previously unrecognized neutral loss of HNO associated with a dehydration reaction that leads to products with Δm of 31, 18 and 49 amu (Fig. 4D) that were not observed in free fatty acid fragmentation analysis (55). Notably, HNO loss was specific for nitroalkanes and not for nitroalkenes, a result confirmed by comparison with synthetic nitro-stearic and nitro-oleic standards (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The cellular distribution of NO2-FA and their metabolites will impact physiological responses. Also, fatty acid CoA thioesterification will significantly modulate pathways of intracellular processing (56, 57). The analysis of free NO2-FA and TAG-esterified NO2-FA levels in adipocyte studies showed a preferential extracellular partitioning of β–oxidized nitroalkene metabolites (NO2-16:1 and NO2-14:1) (inset, Fig. 3D). Michael addition reactions will be favored in the thiol-rich intracellular compartment, predominantly mediating the formation of glutathione (GSH) adducts that are exported via the multidrug resistance protein-1 (35, 41, 58). In this regard, the extracellular milieu is low in reduced thiols compared with intracellular GSH (10-40 μM vs 8 mM GSH respectively) and protein thiols (59). As GSH-NO2-FA adducts are reversible (2), a new equilibrium will be established in the extracellular compartment that will promote β–elimination release of free NO2-FA in extracellular milieu. The short-chain and more hydrophilic β–oxidized and reduced nitroalkane metabolites (NO2-12:0 and NO2-14:0) were enriched in the intracellular compartment (inset in Fig. 3D) as opposed to the longer chain and more hydrophobic nitro-containing species (NO2-16:0 and NO2-18:0). This partitioning based on fatty acyl chain length may be a consequence of differential trans-membrane transport, thioesterase activities that modulate pools of CoA or substrate preferences of diglyceride acyltransferases (DGATs), all of which could impact relative metabolite levels. The C16 fatty acids are the major components of TAG and preferential substrates for TAG synthesis in adipocytes, which is confirmed by the significant incorporation of NO2-16:0 following the addition of NO2-OA (Fig. 3E) (60–62). Interestingly, while NO2-OA was detected as free NO2-FA after lipase hydrolysis of adipocyte TAG, there was no evidence of electrophilic NO2-FA-TAG. Several factors may impair the detection of these species via the direct analysis of NO2-FA-TAG. The chromatographic resolution of free fatty acids is greater than for TAG. This is of relevance, since the combination of a high NO2-FA/NO2-OA relative ratio, up to 50 for C16-C18 chain length nitroalkanes (Fig. 3A), and the lower chromatographic resolution could mask the detection of co-eluting low abundance species. In addition, the analysis of NO2-FA-TAG was performed using a high resolution MS to obtain structural data, while the analysis of NO2-FA used a triple quadrupole MS, further enhancing an ability to detect less abundant species with high sensitivity.

In adipocytes, non-electrophilic NO2-FA-TAG mainly consisted of saturated, monounsaturated C14-C16-C18 followed by C15-C17 chain length fatty acids (Supplementary Table 1), in agreement with reports that 3T3-L1 adipocytes contain more than 20% of odd chain fatty acids (60). The positional analysis of the most abundant non-electrophilic NO2-FA-TAG suggested preferential incorporation of nitroalkane substituents in sn-2 position (Table 1). However, the co-elution of structural isomers, containing common diacyl product ions, did not allow any further positional analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4A) (42). In some cases, the minor contribution of the co-eluting NO2-FA-TAG to the common MS2 fragment allowed the precise identification of positional isomers (Supplementary Fig. 4B) (24, 42).

Oral administration of labeled or modified fatty acids has been widely used to assess the formation of TAG in vivo (63, 64). The analysis of plasma NO2-FA-TAG after oral gavage resulted in a spectrum of similar TAG species as when triacylglycerides were obtained from NO2-OA supplemented adipocytes, with non-electrophilic NO2-FA being the predominant species detected in both cases. Even though NO2-18:0-containing- plasma TAG were confirmed in these experiments, the detection of these species remains challenging as overall they represent a small percentage of the total TAG in plasma. Moreover, chromatographic separations result in a high number of species having different possible acyl chain and isomeric compositions.

In summary, unsaturated fatty acid-containing TAG are targets for nitration reactions during digestive or inflammatory conditions and can become a substrate for subsequent mobilization of the free fatty acid upon lipase hydrolysis. The pool of NO2-FA metabolites can also be re-esterified in adipocytes and, during enterohepatic transit, yield various NO2-FA-TAG species preferentially consisting of nitroalkanes rather than nitroalkenes. New insight into the metabolism, distribution and incorporation of NO2-OA showed that: 1) NO2-OA is reduced by nitroalkene reductases and undergoes mitochondrial β-oxidation; 2) the electrophilicity and lipophilicity of nitroalkenes and nitroalkanes affect intra- and extracellular distribution; 3) NO2-OA is esterified into TAG with the potential generation of electrophilic NO2-FA-TAG; and 4) nitroalkanes were preferentially esterified into TAG as opposed to nitroalkenes. On this basis, unsaturated fatty acid nitration in the gastric compartment can contribute to the formation of esterified NO2-FA in vitro and in vivo and participate in metabolic and anti-inflammatory signaling responses.

Supplementary Material

Triacylglycerides are nitrated under in vitro gastric conditions.

Nitro-triacylglycerides characterization by HPLC-MS/MS.

Nitro fatty acids are esterified into adipocyte and plasma triacylglycerides.

Esterification of nitro-fatty acids favors nitroalkanes over nitroalkenes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from NIH grants R01-HL058115, R01-HL64937, P30-DK072506, P01-HL103455 (BAF), R01 AT006822 and 14GRNT20170024 (FJS), Gilead Sciences Research Scholars Program in PAH (N.K.H.K.). BAF and FJS acknowledge financial interest in Complexa, Inc.

Abbreviations

- 8:0

octanoic acid

- 12:1

dodecenoic acid

- 14:0

tetradecanoic acid

- 14:1

tetradecenoic acid

- 15:0

pentadecanoic acid

- 15:1

pentadecenoic acid

- 16:0

hexadecanoic acid

- 16:1

hexadecenoic acid

- 17:0

heptadecanoic acid

- 17:1

heptadecenoic acid

- 18:0

stearic acid (octadecanoic acid)

- 18:1

oleic acid (octadec-9-enoic acid)

- 1,2-DPG

1,2-dipalmitoylglycerol

- 1,3-DPG

1,3-dipalmitoylglycerol

- CID

collision induced dissociation

- CLA

conjugated linoleic acid [octadeca-(9Z,11E)-dienoic acid]

- CLA-TAG

dipalmitoyl-conjugated-linoleoylglycerol

- CoA

coenzyme A

- DGAT

diglyceride acyltransferase

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- ESI

electro spray ionization

- EPI

enhanced product ion scan

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- FWHM

full width at half maximum

- GC

gas chromatography

- GSH

glutathione

- HBA

hexane/methyl tert-butyl ether/acetic acid solution

- HBSS

Hank’s balanced salt solution

- HNO2

nitrous acid

- HPLC-MS/MS

high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- HPLC-APCI-MS/MS

high performance liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-tandem mass spectrometry

- HPLC-ESI-MS/MS

high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry

- HPLC-HR-MS/MS

high performance liquid chromatography-coupled high resolution-tandem mass spectrometry analysis

- Keap1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring scan mode

- MS

mass spectrometer

- m/z

mass-to-charge ratio

- NH3

ammonia

- N2O3

dinitrogen trioxide

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NaNO2

sodium nitrite

- NF-kB

nuclear factor kappa B

- •NO

nitric oxide

- •NO2

nitrogen dioxide

- NO2−

nitrite

- NO3−

nitrate

- NO2-oxo-OA-TAG

dipalmitoyl-nitro-oxo-octadec-10-enoylglycerol

- NO2-OH-OA-TAG

dipalmitoyl-nitrohydroxyoctadec-10-enoylglycerol

- NO2-OOH-OA-TAG

dipalmitoyl-nitrohydroperoxyoctadec-10-enoylglycerol

- NO2-CLA-TAG

1,3-dipalmitoyl-2-nitro-conjugated-linoleoylglycerol

- NO2-CLA

nitro-conjugated linoleic acid

- NO2-FA

electrophilic nitro-fatty acids

- NO2-FA-TAG

nitro-fatty acid-containing-triglycerides

- NO2-OA, NO2-18:1

nitro-oleic acid (10-nitro-octadec-9-enoic acid)

- NO2-[13C18]OA

nitro-[13C18]octadec-9-enoic acid

- NO2-18:0

nitro-stearic acid

- NO2-[15N/D4]18:0

[15N]nitro-[D4]octadecanoic acid

- NO2-[15N/D4]18:1

[15N]nitro-[D4]octadecenoic acid

- NO2-16:0

nitro-hexadecanoic acid

- NO2-16:1

nitro-hexadecenoic acid

- NO2-14:0

nitro-tetradecanoic acid

- NO2-14:1

nitro-tetradecenoic acid

- NO2-12:0

nitro-dodecanoic acid

- NO2-12:1

nitro-dodecenoic acid

- Nrf2

nuclear transcription factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- OA

oleic acid

- SPE

solid phase extraction

- TAG

triacylglycerides

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1

- 9-NO2-CLA

9-nitro-octadeca-(9,11)-dienoic acid

- 12-NO2-CLA

12-nitro-octadeca-(9,11)-dienoic acid. The designations “9-NO2-” and “12-NO2-”CLA are used herein to describe the position of the nitro group in conjugated dienes and do not refer to IUPAC nomenclature.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Freeman BA, Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Napolitano A, d’Ischia M. Nitro-fatty acid formation and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15515–15519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800004200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker LM, Baker PR, Golin-Bisello F, Schopfer FJ, Fink M, Woodcock SR, Branchaud BP, Radi R, Freeman BA. Nitro-fatty acid reaction with glutathione and cysteine. Kinetic analysis of thiol alkylation by a Michael addition reaction. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31085–31093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704085200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batthyany C, Schopfer FJ, Baker PR, Duran R, Baker LM, Huang Y, Cervenansky C, Branchaud BP, Freeman BA. Reversible post-translational modification of proteins by nitrated fatty acids in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20450–20463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602814200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schopfer FJ, Cipollina C, Freeman BA. Formation and signaling actions of electrophilic lipids. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5997–6021. doi: 10.1021/cr200131e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui T, Schopfer FJ, Zhang J, Chen K, Ichikawa T, Baker PR, Batthyany C, Chacko BK, Feng X, Patel RP, Agarwal A, Freeman BA, Chen YE. Nitrated fatty acids: Endogenous anti-inflammatory signaling mediators. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35686–35698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603357200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villacorta L, Zhang J, Garcia-Barrio MT, Chen XL, Freeman BA, Chen YE, Cui T. Nitro-linoleic acid inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H770–776. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00261.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kansanen E, Bonacci G, Schopfer FJ, Kuosmanen SM, Tong KI, Leinonen H, Woodcock SR, Yamamoto M, Carlberg C, Yla-Herttuala S, Freeman BA, Levonen AL. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids activate NRF2 by a KEAP1 cysteine 151-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:14019–14027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sculptoreanu A, Kullmann FA, Artim DE, Bazley FA, Schopfer F, Woodcock S, Freeman BA, de Groat WC. Nitro-oleic acid inhibits firing and activates TRPV1- and TRPA1-mediated inward currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons from adult male rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333:883–895. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.163154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonacci G, Schopfer F, Salvatore S, Rudolph TK, Rudolph V, Khoo K, Koenitzer J, Golin-Bisello F, Baker PR, Shores D, Woodcock SR, Cole MP, Postlethwait E, Freeman BA. Conjugated linoleic acid a preferential substrate for fatty acid nitration. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4407–44082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudolph V, Rudolph TK, Schopfer FJ, Bonacci G, Woodcock SR, Cole MP, Baker PR, Ramani R, Freeman BA. Endogenous generation and protective effects of nitro-fatty acids in a murine model of focal cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:155–166. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Napolitano A, Camera E, Picardo M, d’Ischia M. Acid-promoted reactions of ethyl linoleate with nitrite ions: formation and structural characterization of isomeric nitroalkene, nitrohydroxy, and novel 3-nitro-1,5-hexadiene and 1,5-dinitro-1, 3-pentadiene products. J Org Chem. 2000;65:4853–4860. doi: 10.1021/jo000090q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trostchansky A, Bonilla L, Gonzalez-Perilli L, Rubbo H. Nitro-fatty acids: formation, redox signaling, and therapeutic potential. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1257–1265. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelley EE, Baust J, Bonacci G, Golin-Bisello F, Devlin JE, St Croix CM, Watkins SC, Gor S, Cantu-Medellin N, Weidert ER, Frisbee JC, Gladwin MT, Champion HC, Freeman BA, Khoo NK. Fatty acid nitroalkenes ameliorate glucose intolerance and pulmonary hypertension in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;101:352–363. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazzari M, Trostchansky A, Schopfer FJ, Salvatore SR, Sanchez-Calvo B, Vitturi D, Valderrama R, Barroso JB, Radi R, Freeman BA, Rubbo H. Olives and olive oil are sources of electrophilic Fatty Acid nitroalkenes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charles RL, Rudyk O, Prysyazhna O, Kamynina A, Yang J, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Freeman BA, Eaton P. Protection from hypertension in mice by the Mediterranean diet is mediated by nitro fatty acid inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8167–8172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402965111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodpaster BH, Wolf D. Skeletal muscle lipid accumulation in obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2004;5:219–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pankow JS, Duncan BB, Schmidt MI, Ballantyne CM, Couper DJ, Hoogeveen RC, Golden SH S. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities. Fasting plasma free fatty acids and risk of type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Diabetes care. 2004;27:77–82. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brunengraber DZ, McCabe BJ, Kasumov T, Alexander JC, Chandramouli V, Previs SF. Influence of diet on the modeling of adipose tissue triglycerides during growth. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E917–925. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00128.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frayn KN. Adipose tissue as a buffer for daily lipid flux. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1201–1210. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0873-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christie WW, Hunter ML, Vernon RG. Triacylglycerol biosynthesis in rat adipose-tissue homogenates. Biochem J. 1976;159:571–577. doi: 10.1042/bj1590571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith GG, Wetzel WH. The Effect of Molecular Size and Structure on the Pyrolysis of Esters. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:875–879. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leskinen H, Suomela JP, Kallio H. Quantification of triacylglycerol regioisomers in oils and fat using different mass spectrometric and liquid chromatographic methods. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:2361–2373. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrera LC, Potvin MA, Melanson JE. Quantitative analysis of positional isomers of triacylglycerols via electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry of sodiated adducts. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2010;24:2745–2752. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAnoy AM, Wu CC, Murphy RC. Direct qualitative analysis of triacylglycerols by electrospray mass spectrometry using a linear ion trap. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:1498–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murphy RC, Axelsen PH. Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Long-Chain Lipids. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2011;30:579–599. doi: 10.1002/mas.20284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hunter JE. Studies on effects of dietary fatty acids as related to their position on triglycerides. Lipids. 2001;36:655–668. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kritchevsky D, Tepper SA, Chen SC, Meijer GW, Krauss RM. Cholesterol vehicle in experimental atherosclerosis. 23. Effects of specific synthetic triglycerides. Lipids. 2000;35:621–625. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0565-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Gelhaus SL, Schopfer FJ. Nitrated fatty acids: synthesis and measurement. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;59:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kodali DR, Tercyak A, Fahey DA, Small DM. Acyl migration in 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol. Chem Phys Lipids. 1990;52:163–170. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(90)90111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khoo NK, Mo L, Zharikov S, Kamga-Pride C, Quesnelle K, Golin-Bisello F, Li L, Wang Y, Shiva S. Nitrite augments glucose uptake in adipocytes through the protein kinase A-dependent stimulation of mitochondrial fusion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;70:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou W. Separation of Lipids by Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Prot Exchange 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han XL, Gross RW. Quantitative analysis and molecular species fingerprinting of triacylglyceride molecular species directly from lipid extracts of biological samples by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2001;295:88–100. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudolph V, Schopfer FJ, Khoo NK, Rudolph TK, Cole MP, Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Groeger AL, Golin-Bisello F, Chen CS, Baker PR, Freeman BA. Nitro-fatty acid metabolome: saturation, desaturation, beta-oxidation, and protein adduction. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1461–1473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802298200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvatore SR, Vitturi DA, Baker PRS, Bonacci G, Koenitzer JR, Woodcock SR, Freeman BA, Schopfer FJ. Characterization and quantification of endogenous fatty acid nitroalkene metabolites in human urine. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:1998–2009. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M037804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mottram HR, Evershed RP. Structure analysis of triacylglycerol positional isomers using atmospheric pressure chemical ionisation mass spectrometry. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8593–8596. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marzilli LA, Fay LB, Dionisi F, Vouros P. Structural characterization of triacylglycerols using electrospray ionization-MSn ion-trap MS. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2003;80:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hvattum E. Analysis of triacylglycerols with non-aqueous reversed-phase liquid chromatography and positive ion electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2001;15:187–190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0231(20010215)15:3<187::AID-RCM211>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Green H, Meuth M. Established Pre-Adipose Cell Line and Its Differentiation in Culture. Cell. 1974;3:127–133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schopfer FJ, Batthyany C, Baker PR, Bonacci G, Cole MP, Rudolph V, Groeger AL, Rudolph TK, Nadtochiy S, Brookes PS, Freeman BA. Detection and quantification of protein adduction by electrophilic fatty acids: mitochondrial generation of fatty acid nitroalkene derivatives. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1250–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malone M, Evans JJ. Determining the relative amounts of positional isomers in complex mixtures of triglycerides using reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Lipids. 2004;39:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark SR, Guy CJ, Scurr MJ, Taylor PR, Kift-Morgan AP, Hammond VJ, Thomas CP, Coles B, Roberts GW, Eberl M, Jones SA, Topley N, Kotecha S, O’Donnell VB. Esterified eicosanoids are acutely generated by 5-lipoxygenase in primary human neutrophils and in human and murine infection. Blood. 2011;117:2033–2043. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-278887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stafforini DM, Sheller JR, Blackwell TS, Sapirstein A, Yull FE, McIntyre TM, Bonventre JV, Prescott SM, Roberts LJ., 2nd Release of free F2-isoprostanes from esterified phospholipids is catalyzed by intracellular and plasma platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4616–4623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bacot S, Bernoud-Hubac N, Baddas N, Chantegrel B, Deshayes C, Doutheau A, Lagarde M, Guichardant M. Covalent binding of hydroxy-alkenals 4-HDDE, 4-HHE, and 4-HNE to ethanolamine phospholipid subclasses. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:917–926. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200450-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly ML, Kolver ES, Bauman DE, Van Amburgh ME, Muller LD. Effect of intake of pasture on concentrations of conjugated linoleic acid in milk of lactating cows. J Dairy Sci. 1998;81:1630–1636. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(98)75730-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chin SF, Liu W, Storkson JM, Ha YL, Pariza MW. Dietary sources of conjugated dienoic isomers of linoleic acid, a newly recognized class of anticarcinogens. J Food Comp Anal. 1992;5:185–197. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hord NG, Tang Y, Bryan NS. Food sources of nitrates and nitrites: the physiologic context for potential health benefits. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1–10. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:156–167. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lundberg JO, Gladwin MT, Ahluwalia A, Benjamin N, Bryan NS, Butler A, Cabrales P, Fago A, Feelisch M, Ford PC, Freeman BA, Frenneaux M, Friedman J, Kelm M, Kevil CG, Kim-Shapiro DB, Kozlov AV, Lancaster JR, Jr, Lefer DJ, McColl K, McCurry K, Patel RP, Petersson J, Rassaf T, Reutov VP, Richter-Addo GB, Schechter A, Shiva S, Tsuchiya K, van Faassen EE, Webb AJ, Zuckerbraun BS, Zweier JL, Weitzberg E. Nitrate and nitrite in biology, nutrition and therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:865–869. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E. Biology of nitrogen oxides in the gastrointestinal tract. Gut. 2012;62:616–629. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Napolitano A, Camera E, Picardo M, d’Ishida M. Reactions of hydro(pero)xy derivatives of polyunsaturated fatty acids/esters with nitrite ions under acidic conditions. Unusual nitrosative breakdown of methyl 13-hydro(pero)xyoctadeca-9,11-dienoate to a novel 4-nitro-2-oximinoalk-3-enal product. J Org Chem. 2002;67:1125–1132. doi: 10.1021/jo015973b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vitturi DA, Chen CS, Woodcock SR, Salvatore SR, Bonacci G, Koenitzer JR, Stewart NA, Wakabayashi N, Kensler TW, Freeman BA, Schopfer FJ. Modulation of nitro-fatty acid signaling: prostaglandin reductase-1 is a nitroalkene reductase. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:25626–25637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.486282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kelley EE, Batthyany CI, Hundley NJ, Woodcock SR, Bonacci G, Del Rio JM, Schopfer FJ, Lancaster JR, Jr, Freeman BA, Tarpey MM. Nitro-oleic acid, a novel and irreversible inhibitor of xanthine oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:36176–36184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802402200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonacci G, Asciutto E, Woodcock S, Salvatore S, Freeman B, Schopfer F. Gas-phase fragmentation analysis of nitro fatty acids. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1534–1551. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0185-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golej DL, Askari B, Kramer F, Barnhart S, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Pennathur S, Bornfeldt KE. Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4 modulates prostaglandin E(2) release from human arterial smooth muscle cells. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:782–793. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M013292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watkins PA, Ellis JM. Peroxisomal acyl-CoA synthetases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:1411–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alexander RL, Bates DJ, Wright MW, King SB, Morrow CS. Modulation of nitrated lipid signaling by multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1): glutathione conjugation and MRP1-mediated efflux inhibit nitrolinoleic acid-induced, PPARgamma-dependent transcription activation. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7889–7896. doi: 10.1021/bi0605639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Banerjee R. Redox outside the box: linking extracellular redox remodeling with intracellular redox metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:4397–4402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.287995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Glenn KC, Shieh JJ, Laird DM. Characterization of 3T3-L1 storage lipid metabolism: effect of somatotropin and insulin on specific pathways. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1115–1124. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.3.1505455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guo W, Choi JK, Kirkland JL, Corkey BE, Hamilton JA. Esterification of free fatty acids in adipocytes: a comparison between octanoate and oleate. Biochem J. 2000;349:463–471. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo W, Lei T, Wang T, Corkey BE, Han J. Octanoate inhibits triglyceride synthesis in 3T3-L1 and human adipocytes. J Nutr. 2003;133:2512–2518. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.8.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McLaren DG, He T, Wang SP, Mendoza V, Rosa R, Gagen K, Bhat G, Herath K, Miller PL, Stribling S, Taggart A, Imbriglio J, Liu J, Chen D, Pinto S, Balkovec JM, Devita RJ, Marsh DJ, Castro-Perez JM, Strack A, Johns DG, Previs SF, Hubbard BK, Roddy TP. The use of stable-isotopically labeled oleic acid to interrogate lipid assembly in vivo: assessing pharmacological effects in preclinical species. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:1150–1161. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M011049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McLaren DG, Cardasis HL, Stout SJ, Wang SP, Mendoza V, Castro-Perez JM, Miller PL, Murphy BA, Cumiskey AM, Cleary MA, Johns DG, Previs SF, Roddy TP. Use of [13C18] oleic acid and mass isotopomer distribution analysis to study synthesis of plasma triglycerides in vivo: analytical and experimental considerations. Anal Chem. 2013;85:6287–6294. doi: 10.1021/ac400363k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.