Abstract

Background & Aims

The prevalence and risk factors of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) in Asian countries are unclear. Studies report a wide range of BE prevalence in Asian countries. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the prevalence of BE, its temporal changes and risk factors in Asian countries.

Methods

Two investigators performed independent literature searches using PubMed and EMBASE databases, and subsequent data abstraction for studies had to meet several set inclusion and exclusion criteria. Pooled BE prevalence was calculated using a random-effect model. Estimates of relative risk for possible risk or protective factors were also calculated.

Results

A total of 51 studies (N = 453,147), mainly from Eastern Asia, were included. The pooled prevalence of endoscopic BE was 7.8% (95% CI = 5.0 – 12.1; 23 studies) and of histologically confirmed BE was 1.3% (95% CI = 0.7 – 2.2; 28 studies). Most (82.1%) of histologic BE was short-segment BE (<3 cm). There was a trend toward an increase in prevalence of BE over time from 1991 to 2014, especially in Eastern Asian countries. Within BE cohorts, pooled prevalence of low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma was 6.9%, 3.0% and 2.0%, respectively. Reflux symptoms, male sex, hiatus hernia, and smoking were associated with a significantly increased risk of histologic BE in patients with BE compared with patients without BE. However, half of the patients with histologic BE did not have reflux symptoms.

Conclusions

BE is not uncommon in Asian countries and seems to share similar risk factors and potential for neoplastic progression to that seen in Western countries.

Keywords: Barrett’s esophagus, systematic review, meta-analysis, prevalence, risk factors

Introduction

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is commonly defined as a change of any length in the distal esophageal epithelium that can be recognized as columnar-type mucosa at endoscopy and is confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy of the tubular esophagus.1 Other BE definitions do not require the presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia in histology.2, 3 BE is a precancerous lesion for esophageal adenocarcinoma,4 with a relative risk of adenocarcinoma among patients with BE compared with the general population of 11.3 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 8.8 – 14.4).5

The prevalence of BE and the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma have been increasing in Western countries.6, 7 In these populations, BE is highly prevalent in people with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)4; and the rising prevalence of GERD and obesity, combined with the decline in Helicobacter pylori infection, are thought to underlie the increase of the incidence of BE and esophageal adenocarcinoma.8 Similar trends have recently emerged in Asian countries, where the prevalence of GERD symptoms and reflux esophagitis, as well as obesity, has increased.9, 10 However, the effect of these trends on the prevalence of BE is unknown.

The prevalence and risk factors of BE in Asian countries are unclear. Studies report a wide range of BE prevalence (0.06 – 43.0%) in Asian countries.9, 11, 12 This variation may be due to the different time periods, study populations, and BE definitions.13, 14 A few studies also examined possible risk or protective factors for BE in Asia, but the overall patterns are unclear. There is no systematic review or meta-analysis focused on the prevalence or risk factors of BE in Asian countries. In this study, we examined the temporal changes in BE prevalence, regional variations and risk factors for BE in Asian countries.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.15

Data Sources

A literature search was performed using the PubMed and EMBASE databases for articles published from inception through September 2014, which included the terms Barrett’s esophagus, Barrett esophagus, or columnar-lined esophagus combined with epidemiology’, epidemiological, prevalence, incidence or population and Asia or each of 47 Asian countries, as China, Japan, Korea, Mongolia, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Viet Nam, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Palestine, Georgia, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syrian Arab Republic or Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, or Yemen in the title, abstract or list of medical subject heading terms with no language restriction.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All eligible studies had to satisfy the following inclusion criteria: 1) BE defined at least by endoscopic criteria in a cross-sectional or cohort study but not case-control study where it is not possible to calculate the prevalence; and 2) sample size of the examined study population >200 eligible individuals participating in the study8. We excluded studies based on the following criteria: 1) study was not conducted in an Asian country; 2) prevalence of BE was studied only in patient groups limited to those with erosive esophagitis, cancer, or renal failure or the obese; and 3) conference abstracts because of their insufficient information. We defined endoscopic BE as abnormal columnar esophageal epithelium suggestive of a columnar-lined distal esophagus without histologic confirmation; histologic BE was defined as the presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia in endoscopic BE. When similar data were identified in multiple reports, we included only the report with the most complete and recent relevant data.

Selection of Studies

Two authors independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of studies identified in the search, based on prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and, when not possible, then in consultation with the senior investigator (HE). We also performed recursive search of bibliographies of existing narrative reviews and published studies.

Data Extraction

Two investigators independently extracted data from each study and entered them into a Microsoft Access® database. The extracted information included citation information; study location (geographic location, country); study population (e.g., symptomatic patients, health screening mainly for gastric cancer, population-based); study period; study design (prospective, retrospective); BE definition (endoscopic BE or histologic BE); BE extent, based on Prague Circumferential and Maximal (C & M) criteria16; way histologic diagnosis was performed; landmark for esophago-gastric junction (EGJ); definition of short-segment BE; sample size; demographic data for study population (e.g., age, sex distribution, etc.); frequency of erosive esophagitis; frequency/proportion of endoscopic and/or histologic BE from patients/population examined; demographic data for patients with BE (e.g., age, sex); presence of esophageal dysplasia or adenocarcinoma in BE; and associated risk factors for BE (e.g., obesity, H. pylori, smoking, hiatus hernia, or reflux symptoms).

The methodological quality of each study was assessed, based on a predefined scale, according to 8 items defined as yes/no, as: 1) random sample or whole population; 2) unbiased sampling frame; 3) adequate sample size (>200 subjects); 4) standard BE measures; 5) outcome (i.e., BE), measured by unbiased assessors; 6) adequate response rate (70%) and refusers described; 7) confidence intervals and subgroup analysis presented; and 8) description of study subjects.17

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes were defined as the prevalence of histologic or endoscopic BE. Subgroup analyses were performed to find any relevant factors (e.g., age, sex distribution, study period) for the prevalence. Geographic areas were categorized as Eastern, South Eastern, South Central, and Western Asia, according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (GLOBOCAN2012, http://globocan.iarc.fr/). The study period in which the researchers conducted their studies (distinct from publication year) was analyzed as a categorical variable (1991–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, and 2010–2014), using the median year of the study period when a study was carried out over 2 years. When the study period was unavailable, the year of study publication was used instead. Studies were categorized according to the sampling frame as population-based, health check-up or screening (screening studies), or symptomatic patients (symptomatic studies), or unspecified. When studies included both screening and symptomatic subjects, they were categorized into symptomatic subjects. Secondary outcomes included risk factors for histologic BE. Proportion of age, male sex, obesity, H. pylori infection, smoking, hiatus hernia, and reflux symptoms were abstracted or calculated in the group between histologic BE and non-BE.

Statistical Analysis

The analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 2 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ), SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) and STATA software version 13.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Calculation of pooled BE prevalence was performed in random-effect models. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed by I2 statistic (i.e., <30%, 30% – 60%, 60% – 75%, and >75%), suggestive of low, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively).18, 19 As part of a sensitivity analysis, we assessed the impact of each study on the combined prevalence by running "Remove-One" analysis (i.e., the meta-analysis is run multiple times each with a different and single study removed). We assessed temporal trends in prevalence of BE in a Poisson regression model and binomial regression analyses. Estimates of relative risk for possible risk or protective factors were calculated as prevalence odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs and pooled, using a random-effect model. P values were calculated, using the Wald χ2 test.

Results

Search Results

Our search strategy identified 297 articles in PubMed and 167 articles in EMBASE. Based on the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria, 55 and 6 potentially eligible articles were selected for further review from PubMed and EMBASE, respectively (Figure 1). After excluding duplicate reports on the same population,20–24 we included 51 studies (1 study reported 2 distinct cohorts) (N = 453,147) in our analysis (Supple Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of systematic literature searches.

Overview of the Included Studies

The number of subjects examined in each study ranged from 25325 to 139,416.26 Twenty-eight studies (total 298,850 subjects) reported histologic BE prevalence,11, 26–52 and twenty-three studies (154,297 subjects) reported endoscopic BE prevalence only.3, 12, 25, 53–71 Forty-seven studies reported the study period, whereas the remaining four studies did not. The oldest study was conducted between 1991 and 1992 and published in 1997.27 Seven studies (N = 63,996 subjects) were conducted from 1991–1999, 16 studies (N = 132,271) were conducted from 2000–2004, 24 studies (N = 243,411) were conducted from 2005–2009, and four studies (N = 13,469) were conducted from 2010–2014. There was only 1 population-based study (N = 1,029),68 11 screening studies (N = 89,651), 37 symptomatic studies (N = 336,933), and 2 studies with an unspecified sampling frame (N = 25,534). Most studies (38 studies, N = 424,371) were conducted in Eastern Asia, 4 studies (N = 5,413) were conducted in South Eastern Asia, 5 studies (N = 2,928) were conducted in South Central Asia, and 4 studies (N = 20,435) were conducted in Western Asia.

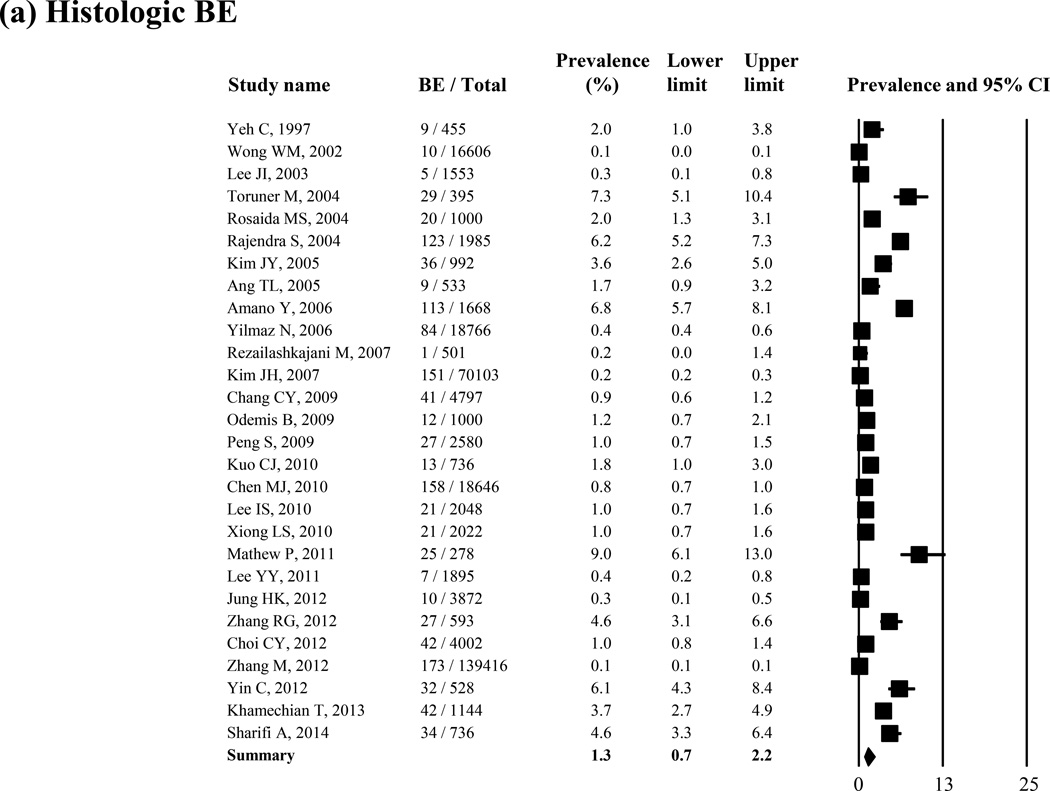

Prevalence of Histologic BE

Histologic BE was reported in 28 studies (N = 298,850). The lowest prevalence was 0.06% (10/16,606),11 and the highest was 8.9% (25/278).45 Overall, the pooled prevalence of histologic BE was 1.3% (95% CI = 0.7 – 2.2) in the random-effect model (I2 = 99%) (Figure 2 (a)). In 2 studies in which biopsy specimens were taken only from pink mucosa 3cm or more above the squamocolumnar junction, the prevalence of histologic BE was 0.3% and 0.2%, respectively.28, 36 In the sensitivity analysis excluding these 2 studies, the pooled prevalence of histologic BE was 1.4% (95% CI = 0.7 – 2.2). The Remove-One analysis did not show any variation in the pooled BE prevalence (Supple Figure 1 (a)).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of histologic BE (N = 28 studies) (a) and endoscopic BE only (23 studies) (b)

As shown in Table 1(a), the prevalence of histologic BE was not associated with age or sex distribution. There was a trend toward an increase in prevalence of histologic BE over time from 0.8% for 1991–1999, to 1.5% for 2000–2004, to 1.2% for 2005–2009 and to 2.2% for 2010–2014, despite there being an absence of a trend in increase in the negative binomial model (P = 0.97). Histologic BE prevalence was highest in studies from South Central Asia, followed by South Eastern, Western, and Eastern Asia. In a sensitivity analysis limited only in East and Southeast Asian countries (21 studies), the prevalence of histologic BE was 0.9% (95% CI = 0.9 – 1.0). The prevalence of histologic BE was higher in symptomatic studies than that in screening studies, although these differences did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.12).

Table 1.

The prevalence of histologic BE (a) and endoscopic BE only (b)

| (a) Histologic BE | ||||

| Number of studies | BE | Total | Prevalence of BE (%) (95% CI) | |

| Average age | ||||

| ≥50 | 7 | 408 | 32897 | 1.5 (0.7 – 3.3) |

| <50 | 9 | 185 | 12705 | 1.6 (0.8 – 3.0) |

| Not specified | 12 | 682 | 253248 | 1.0 (0.4 – 2.8) |

| % Male | ||||

| ≥0.5 | 15 | 824 | 177257 | 2.0 (0.9 – 4.6) |

| <0.5 | 7 | 152 | 8668 | 1.8 (0.9 – 3.4) |

| Not specified | 6 | 299 | 112925 | 0.3 (0.2 – 0.6) |

| Study period (enrolled year or published year) | ||||

| 1991–1999 | 4 | 226 | 37812 | 0.8 (0.1 – 5.1) |

| 2000–2004 | 7 | 339 | 76252 | 1.5 (0.3 – 6.3) |

| 2005–2009 | 15 | 634 | 180048 | 1.2 (0.6 – 2.6) |

| 2010–2014 | 2 | 76 | 4738 | 2.2 (0.5 – 9.1) |

| Geographic area | ||||

| Eastern Asia | 17 | 889 | 270617 | 0.9 (0.5 – 1.9) |

| South-Eastern Asia | 4 | 159 | 5413 | 1.7 (0.6 – 5.3) |

| South-Central Asia | 4 | 102 | 2659 | 4.1 (2.2 – 7.6) |

| Western Asia | 3 | 125 | 20161 | 1.6 (0.2 – 10.1) |

| Study population | ||||

| Screening | 3 | 79 | 10454 | 0.7 (0.3 – 1.4) |

| Symptomatic | 25 | 1196 | 288396 | 1.4 (0.7 – 2.5) |

| (b) Endoscopic BE only | ||||

| Number of studies | BE | Total | Prevalence of BE (%) (95% CI) | |

| Average age | ||||

| ≥50 | 13 | 6657 | 61861 | 13.9 (8.5 – 21.8) |

| <50 | 5 | 1171 | 34353 | 5.3 (1.8 – 14.5) |

| Not specified | 5 | 2373 | 58083 | 2.4 (0.7 – 7.4) |

| % Male | ||||

| ≥0.5 | 12 | 8255 | 109363 | 9.4 (5.1 – 16.7) |

| <0.5 | 7 | 1557 | 11976 | 13.2 (9.1 – 18.8) |

| Not specified | 4 | 389 | 32958 | 1.7 (1.0 – 2.8) |

| Study period (enrolled year or published year) | ||||

| 1991–1999 | 3 | 380 | 26184 | 2.6 (0.4 – 14.2) |

| 2000–2004 | 9 | 3556 | 56019 | 8.9 (5.4 – 14.3) |

| 2005–2009 | 9 | 5688 | 63363 | 10.0 (4.6 – 20.7) |

| 2010–2014 | 2 | 577 | 8731 | 7.1 (0.2 – 70.6) |

| Geographic area | ||||

| Eastern Asia | 21 | 10111 | 153754 | 7.4 (4.6 – 11.7) |

| South-Central Asia | 1 | 71 | 269 | 26.4 (21.5 – 32.0) |

| Western Asia | 1 | 19 | 274 | 6.9 (4.5 – 10.6) |

| Study population | ||||

| Population-based | 1 | 19 | 1029 | 1.8 (1.2 – 2.9) |

| Screening | 8 | 3680 | 79197 | 5.9 (2.9 – 11.6) |

| Symptomatic | 12 | 6224 | 48537 | 14.4 (8.7 – 23.1) |

| Not specified | 2 | 278 | 25534 | 1.0 (0.8 – 1.4) |

BE, Barrett’s esophagus; CI, confidence interval

Only 14 of 28 studies defined and reported EGJ; most (12 studies) used the proximal margin of the gastric folds, 1 used the distal end of the palisade vessel zone at the distal esophagus, and 1 used both landmarks. The prevalence of histologic BE in 12 studies that defined EGJ as the proximal margin of the gastric folds was 1.5% [95% CI = 0.6 – 4.0]. The distribution of short-segment BE and long-segment BE in histologic BE was reported in 14 of 28 studies. The average weighted proportion of short-segment histologic BE (i.e., <3 cm) was 82.1% (95% CI = 73.7 – 88.2) (Supple Figure 2). Fifteen studies examined the presence of histologic BE in patients with erosive esophagitis. Erosive esophagitis was found in 3.4 – 48.3% of the total study population.36, 44 The prevalence of histologic BE in patients with erosive esophagitis ranged from 0.4%36 to 31.9%,51 and the pooled prevalence was 5.2% (95% CI = 2.8 – 9.5) (Supple Figure 3). On the other hand, the prevalence of histologic BE in patients without erosive esophagitis was 0.9% (95% CI = 0.4 – 1.8). The prevalence of histologic BE was significantly higher in patients with erosive esophagitis than in those with nonerosive esophagitis (pooled OR = 5.94 [95% CI = 3.39 – 10.40]).

Among 28 studies, 14 studies also reported the prevalence of endoscopic BE separate from histologic BE. In these studies, histologic BE was confirmed in 7.9% to 67.7% of endoscopic BE. Overall, histologic BE was confirmed in 31.7% (95% CI = 22.2 – 43.0) of patients with endoscopic BE in the random-effect model (Supple Figure 4).

Prevalence of Endoscopic BE Only

Twenty-three studies reported the prevalence of endoscopic BE only (N = 154,297). Endoscopic BE prevalence ranged from 0.3% (56/19,812)62 to 43.0% (374/869).12 Overall, the average weighted, pooled prevalence of endoscopic BE was 7.8% (95% CI = 5.0 – 12.1) in the random-effect model (I2 = 99%) (Figure 1 (b)). In a sensitivity analysis excluding 1 study with higher prevalence of endoscopic BE,12 the prevalence of endoscopic BE was 7.1% (95% CI = 4.6 – 11.1). The Remove-One analysis did not show any variation (Supple Figure 1 (b)).

Average age and sex distribution in the study population were not associated with the prevalence of endoscopic BE only (Table 1(b)). There was a nonsignificant trend toward a temporal increase in prevalence of endoscopic BE (P = 0.58). Geographically, most of studies were conducted in Eastern Asian countries. In a sensitivity analysis limited only in East and Southeast Asian countries (21 studies), the prevalence of endoscopic BE only was 7.4% (95% CI = 4.6 – 11.7). The prevalence of endoscopic BE was higher in the symptomatic studies than in the screening studies (P = 0.22). The prevalence of endoscopic BE only was 1.8% (95% CI = 1.2 – 2.9) in the population-based study. EGJ was defined in 13 of 23 studies; 6 studies used the proximal margin of the gastric folds; 7 studies used the distal end of the palisade vessel zone at the distal esophagus. The prevalence of endoscopic BE was 11.8% (95% CI = 4.0 – 29.9) for the proximal margin of the gastric folds, and 18.6% (95% CI = 13.6 – 25.1) for the distal end of the palisade vessel zone at the distal esophagus (P = 0.38).

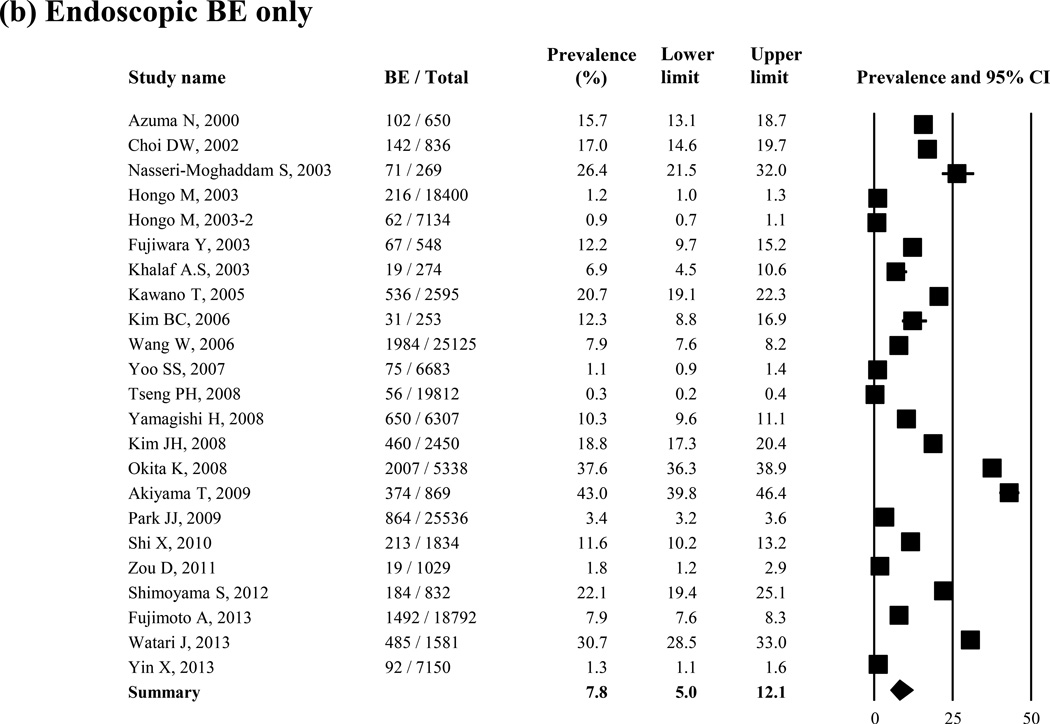

Time Trends

The relationships between study period and the prevalence of histologic or endoscopic BE in Eastern Asian countries are shown in Figure 3. Binomial regression analyses did not show any increasing trend, either for histologic BE or endoscopic BE, despite the fact that the prevalence was gradually increasing. When 1 study examined the histologic BE conducted in 2010–2014 was combined with studies from 2005–2009, the prevalence of histologic BE was 0.3% (95% CI = 0.0 – 9.8) for 1991–1999, 0.8% (95% CI = 0.1 – 11.2) for 2000–2004, and 1.1% (95% CI = 0.5 – 2.5) for 2005–2014, respectively (P = 0.67). The prevalence of endoscopic BE only was 2.6% (95% CI = 0.4 – 14.2) for 1991–1999, 7.8% (95% CI = 4.4 – 13.4) for 2000–2004, 10.0% (95% CI = 4.6 – 20.7) for 2005–2009, and 7.1% (95% CI = 0.2 – 70.6) for 2010–2014, respectively (P = 0.57).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of histologic BE (a) and endoscopic BE (b) categorized by Eastern Asian countries.

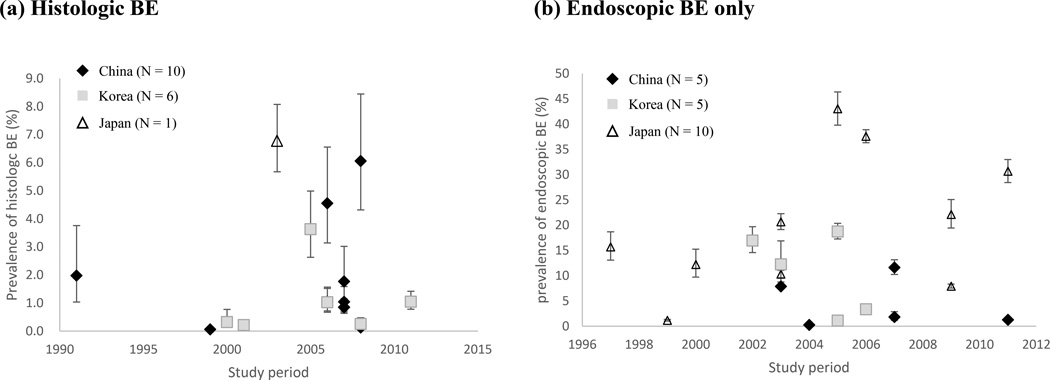

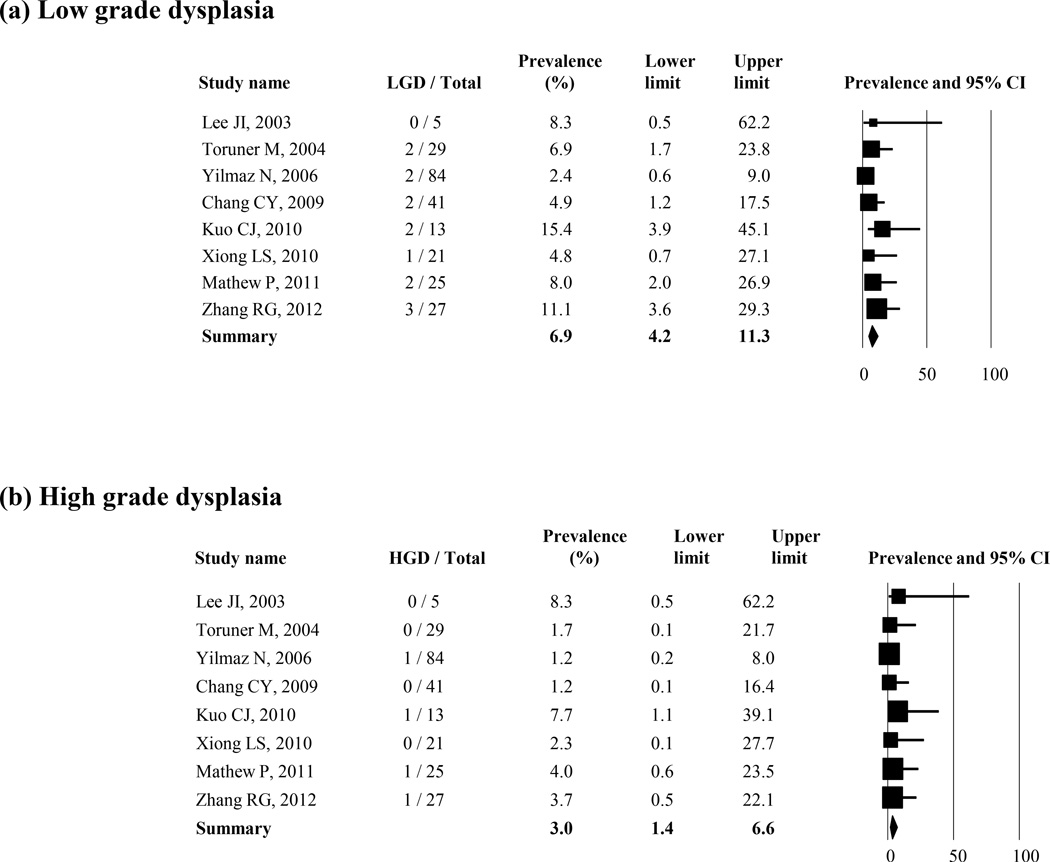

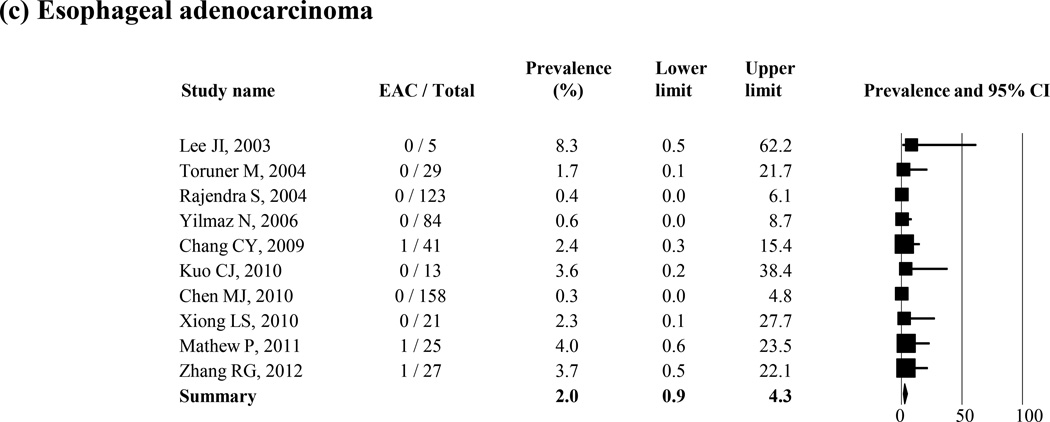

Dysplasia in Histologic BE

The prevalence of low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with histologic BE was reported in 8, 8, and 10 studies, respectively (Figure 4 (a–c)). The average weighted, pooled prevalence was 6.9% (95% CI = 4.2 – 11.3) for low-grade dysplasia (8 studies), 3.0% (95% CI = 1.4 – 6.6) for high-grade dysplasia (8 studies), and 2.0% (95% CI = 0.9 – 4.3) for esophageal adenocarcinoma (10 studies), respectively. Two studies reported the prevalence of unspecified dysplasia in histologic BE; and they were 1.3% and 3.3%, respectively.31, 42

Figure 4.

Prevalence of low (a) or high grade dysplasia (b) and esophageal adenocarcinoma (c) in the patients with histologic BE

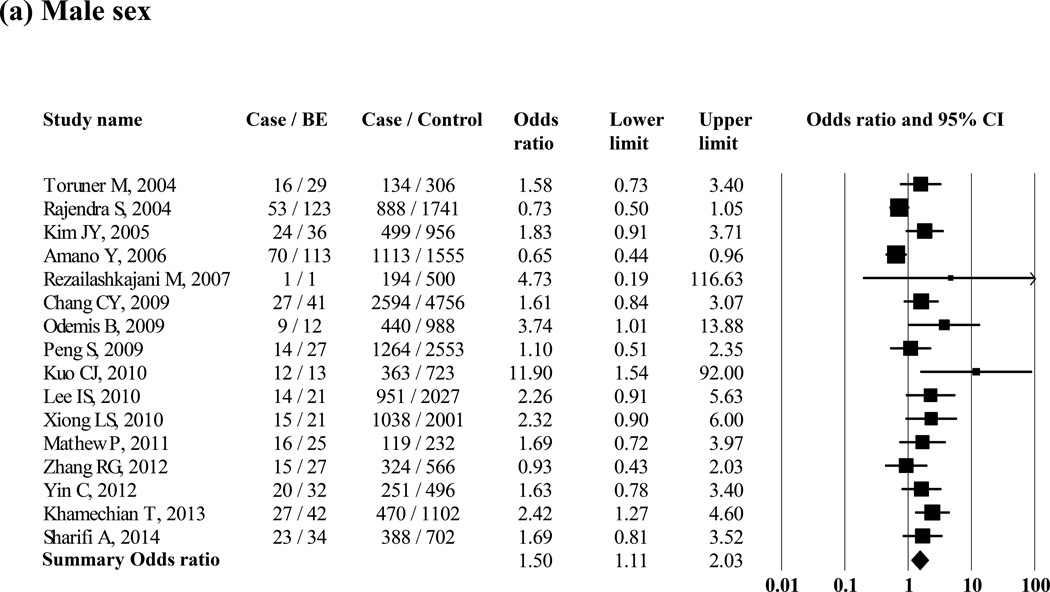

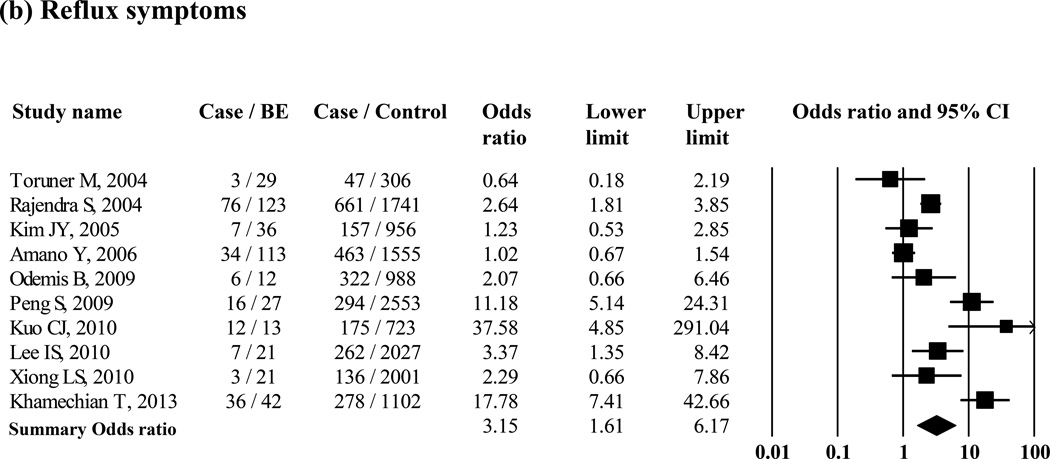

Risk Factors for Histologic BE

Several studies reported on possible risk factors of BE, comparing patients with BE with control groups (Supple Table 2). Ten studies examined differences in age between patients with histologic BE and controls; six studies showed a significantly higher average age in histologic BE, and only one showed a significantly lower average age in histologic BE than that of controls, while the remaining three studies also showed higher average age in patients with BE than in controls. The proportion of men was significantly higher in patients with histologic BE than it was in controls when 16 studies were included (pooled OR = 1.50 [95% CI = 1.11 – 2.03]) (Figure 5 (a)). Hiatus hernia was significantly associated with histologic BE when 15 studies were included (pooled OR = 4.88 [95% CI = 2.93 – 8.13]) (Supple Figure 5 (a)). Smoking was significantly associated with increased risk of histologic BE when 9 studies were included (pooled OR = 1.26 [95% CI = 1.01 – 1.56]) (Supple Figure 5 (b)). The presence of obesity (i.e., defined as body mass index >25) was not associated with histologic BE when 3 studies were included (pooled OR = 3.94 [95% CI = 0.53 – 29.33]) (Supple Figure 5 (c)). Only 1 study examined waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio and showed an association between large waist circumference, but not waist-to-hip ratio, and increased risk of endoscopic BE.70 H. pylori infection was not associated with histologic BE when 6 studies were included (pooled OR = 1.00 [95% CI = 0.81 – 1.23]) (Supple Figure 5 (d)). Ten studies compared reflux symptoms between subjects with histologic BE and controls (Figure 5 (b), and the pooled OR was 3.15 (95% CI = 1.61 – 6.17). The proportion of patients with reflux symptoms was 45.8% in histologic BE patients. Six studies reported the results of multivariate analysis to find independent risk factors for BE. Higher age, male sex, reflux symptoms, and the presence of hiatus hernia were independently associated with BE in their multivariate analyses (Supple Table 3).

Figure 5.

Association between the risk of histologic BE and gender (N = 16 studies) (a) and reflux symptoms (N = 10 studies) (b) in Asian studies

Small-Study Effect “Publication Bias”

The relationship between the sample size and BE prevalence is shown in Supple Figure 6. Higher BE prevalence was generally reported in studies with smaller rather than larger sample size. This effect, however, was not statistically significant in Egger’s test (P = 0.25 for histologic BE, P = 0.46 for endoscopic BE only, Supple Figure 7). Furthermore, Egger’s tests were no significant for low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, or esophageal adenocarcinoma (P = 0.85, 0.74, and 0.22, respectively, Supple Figure 7).

Assess the quality of each study

We assessed the quality of each study and found that: 1) only 1 study was population based68; 2) no study had an unbiased sampling frame; 3) all studies had >200 subjects); 4) all studies used standard measures for BE definition; 5) no study used outcomes evaluated by unbiased assessors; 6) only 2 studies reported the response rate, and in both it was >70%41, 51; 7) all studies reported or calculated the 95% CI, and performed subgroup analyses; and 8) all but 2 studies56 described study subjects. The overall study quality measure ranged from a score of 3 to a score of 5 (of a maximum of 8), with a mean of 4.0.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the prevalence of BE in Asian countries, its temporal trends and risk factors. Our data show that the prevalence of histologically confirmed BE pooled in 28 studies was 1.3% (95% CI = 0.7 – 2.2) and that of endoscopic-only BE was 7.8% (95% CI = 5.0 – 12.1) from 23 studies. These estimates are similar to those in Western countries, where population-based estimates are 1.6% for histologic BE and 10.3% for endoscopic BE72, and studies in symptomatic patients report 6 – 12% prevalence.73, 74 This entity seems similar in the prevalence of neoplasia and risk factors, including reflux symptoms, male sex, hiatus hernia, and smoking.

GERD in Asian countries may have resulted in an increase in BE prevalence in these countries. There was no clear trend of increasing BE prevalence among studies conducted between 1991 and 2014. Two studies reported BE prevalence in the same population over 5 years. Chen et al. from China reported that prevalence of histologic BE increased from 0.6% in 2000 to 1.2% in 2007 in referral endoscopy.42 Zhang et al. also from China, did not find any increasing trend for histologic or endoscopic BE (0.2% in 2005, 0.2% in 2011 for histologic and 1.5% in 2005, 1.4% in 2011 for endoscopic BE, respectively).26

Different definitions for EGJ endoscopic landmarks can influence the reported prevalence of BE. The proximal margin of the gastric mucosal folds is generally accepted as an endoscopic marker of the EGJ.16 On the other hand, the distal margin of the palisade-shaped longitudinal capillary vessels is sometimes considered the EGJ, especially in Japan.3 It is possible that gastric intestinal metaplasia can be considered as BE in the case EGJ was defined as the distal margin of palisade vessels or undefined. Most studies that examined histological BE used the proximal margin of the gastric mucosal folds as the EGJ and diagnosed by the presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia with goblet cell. Importantly, 10 of 23 studies for endoscopic examination only and 14 of 28 studies for histological examination did not show the definition of the EGJ. Endoscopic landmarks for the EGJ need to be stated in the future studies.

The term endoscopic suspected esophageal metaplasia but not endoscopic BE is recommended in the Montreal Definition and Classification of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease.75 To confirm the presence of histologic BE, 4-quadrant biopsies every 1–2 cm for circumferential metaplastic segments is recommended.75 In our study, the overall prevalence of histologic BE in endoscopic BE was 31.7%. The number of biopsies affects the likelihood of detection76 and could have affected the estimates of BE; 10 studies performed 4 biopsies, mostly every 2 cms, but several did not mention the number of biopsies, and none performed 8 biopsies. Further, the diagnostic criteria for endoscopic BE varied among the studies. The Prague C & M criteria were introduced and validated in 200616; however, only 4 studies with histological examination and 3 studies with endoscopic examination used these criteria.

GERD appears to be the main risk factor for BE in Asian countries, just as it is in Western countries. In our study, the prevalence of histologic BE was approximately 6-fold higher in patients with erosive esophagitis than in patients without erosive esophagitis. Moreover, the prevalence of BE was approximately 2-fold higher in the symptomatic studies than in screening studies. Lastly, GERD symptoms were associated with a 3.15-fold increase in the odds of having BE. Nevertheless, the proportion of the patients with reflux symptoms in histologic BE was only 45.8%. Therefore, a screening strategy to detect BE for symptomatic subjects only might be insufficient.

Our findings suggest that histologic BE in Asian countries has a similar potential to develop into esophageal adenocarcinoma as that found in Western countries. The prevalence of low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and esophageal adenocarcinoma in cases with histologically proven BE was comparable with those reported in US studies (1.3 – 9.8% for low-grade dysplasia, 0 – 5.3% for high-grade dysplasia, and 1.3 – 5.7% for esophageal adenocarcinoma, respectively).77–81 In our study, approximately 80% of BE was short-segment BE; and, among the short-segment cases, most were < 1cm.49, 53, 63, 70 It remains unclear whether BE <1cm has a potential risk for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. This uncertainty is related to the low interobserver reliability16, 82 and the exclusion of subjects with BE <1cm from total BE in some studies.32, 43 Further studies are necessary to clarify the clinical implication of BE <1cm.

In studies conducted in Western regions, old age; white race; male sex; chronic heartburn; early onset of GERD symptoms; hiatus hernia; erosive esophagitis obesity with intraabdominal fat distribution; metabolic syndrome; smoking; dietary consumption of fats and red or processed meat; and family history of GERD, BE, or esophageal adenocarcinoma were shown to be risk factors for BE.83–87 On the other hand, H. pylori infection was reported as a protective factor.88 Our study in Asian countries showed that male sex, hiatus hernia, and smoking were associated with histologic BE but not obesity and H. pylori infection. Lack of a positive relationship between obesity and histologic BE in our study might be due to the small number of studies. Regarding H. pylori infection, the prevalence of BE was low, even in Malaysia, where the prevalence of H. pylori infection is also low,46 which does not support the inverse relationship between H. pylori infection and BE.

In addition to the limitations of the individual studies, our meta-analysis has several limitations. First, studies with smaller sample size showed higher BE prevalence than those with larger sample size. Publication bias is a possible explanation for this observation.89 Furthermore, studies had different time periods, study populations, and BE definitions. However, even when we selected studies of only histologic BE in which EGJ was defined as the proximal margin of the gastric folds, the prevalence of histologic BE was 1.5%, which support the evidence that it is not uncommon compared with that of Western countries. In addition, most studies targeted symptomatic patients and, therefore, it is difficult to generalize for asymptomatic or general populations. Second, most studies (38 of 51 studies) were conducted in Eastern Asian countries, with only a few studies from other Asian areas (4 for South Eastern Asia, 5 for South Central Asia, and 4 for Western Asia). Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to all Asian countries. Moreover, there was only one population-based study that examined the prevalence of endoscopic BE only. There was no population-based study examining the prevalence of histologic BE. Diagnosis of histologic BE depends on accurate endoscopic recognition of suspected BE. The Prague C & M criteria were used only in 7 of 51 studies, which suggests that the prevalence of histologic BE in other studies may differ according to inter- and intraobserver variations. Finally, our study showed that the prevalence of low-and high-grade dysplasia were comparable with those of Western regions, however different pathological criteria could have contributed to errors in the high prevalence of dysplasia.90 Despite similar prevalence of histologic BE and dysplasia between Asia and Western, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is considerably lower in Asian than Western. BE prevalence alone does not explain the differences in esophageal adenocarcinoma, however the preponderance of short segment BE may partly explain these differences as it is known that the carcinogenic potential of BE is proportional to segment length. It is also possible that there is a time lag of several decades between the formation of BE and the development of adenocarcinoma. Lastly, it is possible that BE is necessary but not sufficient for the development of adenocarcinoma and other factors that are different in Asian regions such as severity or composition of reflux, obesity and or diet play a role.

In conclusion, endoscopic and histologic BE in Asian countries is not uncommon. The prevalence of low-grade, high-grade dysplasia, and esophageal adenocarcinoma in histologic BE was similar with that of Western countries. GERD symptoms, male sex, hiatus hernia, and smoking were associated with increased risk of histologic BE. These findings may be a prequel for an increase in esophageal adenocarcinoma in these countries. However, targeted strategy only for symptomatic subjects may be insufficient because more than half of the subjects with histologic BE did not have any reflux symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Y Graham and Xiaoying Yu for their assistance in this project, and Sun-Young Lee, Li Jiao and Liang Chen for their translation of Korean and Chinese language papers.

Grant support: This work is funded in part by National Institutes of Health grant NCI R01 116845, and the Texas Digestive Disease Center NIH DK58338. Dr. El-Serag is also supported by NIDDK K24-04-107. This research was supported in part with resources at the VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (#CIN 13-413), at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, TX. The opinions expressed reflect those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the US government or Baylor College of Medicine.

Abbreviations

- BE

Barrett’s esophagus

- CI

confidence interval

- EGJ

esophago-gastric junction

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- OR

odds ratio

- PRISMA

the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Author contributions:

Hashem El-Serag: Funding, conception, design, analysis, interpretation results, manuscript writing, editing, decision to publish.

Seiji Shiota: design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of the data, manuscript writing, editing, decision to publish.

Siddharth Singh: design, interpretation of the data, manuscript editing.

Ashraf Anshasi: data collection, analysis

References

- 1.Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(3):788–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett's oesophagus. Gut. 2014;63(1):7–42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimoyama S, Ogawa T, Toma T, et al. A substantial incidence of silent short segment endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia in an adult Japanese primary care practice. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4(2):38–44. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i2.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaheen NJ, Richter JE. Barrett's oesophagus. Lancet. 2009;373(9666):850–861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60487-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen L, Drewes AM, et al. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett's esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1375–1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Soest EM, Dieleman JP, Siersema PD, et al. Increasing incidence of Barrett's oesophagus in the general population. Gut. 2005;54(8):1062–1066. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.063685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bollschweiler E, Wolfgarten E, Gutschow C, et al. Demographic variations in the rising incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in white males. Cancer. 2001;92(3):549–555. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010801)92:3<549::aid-cncr1354>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Serag HB. Time trends of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung HK. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17(1):14–27. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, et al. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63(6):871–880. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong WM, Lam SK, Hui WM, et al. Long-term prospective follow-up of endoscopic oesophagitis in southern Chinese--prevalence and spectrum of the disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(12):2037–2042. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akiyama T, Inamori M, Akimoto K, et al. Risk factors for the progression of endoscopic Barrett's epithelium in Japan: a multivariate analysis based on the Prague C & M Criteria. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(8):1702–1707. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang CY, Cook MB, Lee YC, et al. Current status of Barrett's esophagus research in Asia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(2):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HS, Jeon SW. Barrett Esophagus in Asia: Same Disease with Different Pattern. Clin Endosc. 2014;47(1):15–22. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett's esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(5):1392–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, et al. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic diseases in Canada. 1998;19(4):170–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 7. Rating the quality of evidence--inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1294–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanwal F, White D. "Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses" in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(11):1184–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akiyama T, Inamori M, Iida H, et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of erosive esophagitis and Barrett's epithelium in Japanese men. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akiyama T, Inamori M, Akimoto K, et al. Gastric surgery is not a risk factor for the development or progression of Barrett's epithelium. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55(86–87):1899–1904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akiyama T, Inamori M, Akimoto K, et al. Gender differences in the age-stratified prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett's epithelium in Japan. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56(89):144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akiyama T, Inamori M, Iida H, et al. Shape of Barrett's epithelium is associated with prevalence of erosive esophagitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(4):484–489. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i4.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng S, Xiong LS, Xiao YL, et al. Prompt upper endoscopy is an appropriate initial management in uninvestigated chinese patients with typical reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(9):1947–1952. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim BC, Yoon YH, Jyung HS, et al. [Clinical characteristics of gastroesophageal reflux diseases and association with Helicobacter pylori infection] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;47(5):363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang M, Fan XS, Zou XP. The prevalence of Barrett`s esophagus remains low in Eastern China. Single-center 7-year descriptive study. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(12):1324–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh C, Hsu CT, Ho AS, et al. Erosive esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus in Taiwan: a higher frequency than expected. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42(4):702–706. doi: 10.1023/a:1018835324210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JI, Park H, Jung HY, et al. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in an urban Korean population: a multicenter study. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(1):23–27. doi: 10.1007/s005350300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toruner M, Soykan I, Ensari A, et al. Barrett's esophagus: prevalence and its relationship with dyspeptic symptoms. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(5):535–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosaida MS, Goh KL. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, reflux oesophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease in a multiracial Asian population: a prospective, endoscopy based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16(5):495–501. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajendra S, Kutty K, Karim N. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of endoscopic esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus: the long and short of it all. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(2):237–242. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000017444.30792.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JY, Kim YS, Jung MK, et al. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20(4):633–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ang TL, Fock KM, Ng TM, et al. A comparison of the clinical, demographic and psychiatric profiles among patients with erosive and non-erosive reflux disease in a multi-ethnic Asian country. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(23):3558–3561. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i23.3558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amano Y, Kushiyama Y, Yuki T, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for Barrett's esophagus with intestinal predominant mucin phenotype. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(8):873–879. doi: 10.1080/00365520500535485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yilmaz N, Tuncer K, Tunçyürek M, et al. The prevalence of Barrett's esophagus and erosive esophagitis in a tertiary referral center in Turkey. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2006;17(2):79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rezailashkajani M, Roshandel D, Shafaee S, et al. High prevalence of reflux oesophagitis among upper endoscopies of Iranian patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19(6):499–506. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32811ebfec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JH, Rhee PL, Lee JH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Barrett's esophagus in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(6):908–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang CY, Lee YC, Lee CT, et al. The application of Prague C and M criteria in the diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus in an ethnic Chinese population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(1):13–20. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Odemiş B, Ciçek B, Zengin NI, et al. Barrett's esophagus and endoscopically assessed esophagogastric junction integrity in 1000 consecutive Turkish patients undergoing endoscopy: a prospective study. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22(8):649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng S, Cui Y, Xiao YL, et al. Prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus in the adult Chinese population. Endoscopy. 2009;41(12):1011–1017. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuo CJ, Lin CH, Liu NJ, et al. Frequency and risk factors for Barrett's esophagus in Taiwanese patients: a prospective study in a tertiary referral center. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(5):1337–1343. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0872-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen MJ, Lee YC, Chiu HM, et al. Time trends of endoscopic and pathological diagnoses related to gastroesophageal reflux disease in a Chinese population: eight years single institution experience. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23(3):201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee IS, Choi SC, Shim KN, et al. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus remains low in the Korean population: nationwide cross-sectional prospective multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(7):1932–1939. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiong LS, Cui Y, Wang JP, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Barrett's esophagus in patients undergoing endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal symptoms. J Dig Dis. 2010;11(2):83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mathew P, Joshi AS, Shukla A, et al. Risk factors for Barrett's esophagus in Indian patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(7):1151–1156. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee YY, Tuan Sharif SE, Syed Abd Aziz SH, et al. Barrett's Esophagus in an Area with an Exceptionally Low Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2011;2011:394734. doi: 10.5402/2011/394734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jung HK, Kim SE, Shim KN, et al. [Association between dyspepsia and upper endoscopic findings] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59(4):275–281. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2012.59.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang RG, Wang CS, Gao CF. Prevalence and pathogenesis of Barrett's esophagus in Luoyang, China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(5):2185–2191. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.5.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi CY, Suh S, Park JS, et al. [The prevalence of Barrett's esophagus and the comparison of Barrett's esophagus with cardiac intestinal metaplasia in the health screening at a secondary care hospital] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;60(4):219–223. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2012.60.4.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin C, Zhang J, Gao M, et al. Epidemiological investigation of Barrett's esophagus in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease in Northwest China. Journal of Medical Colleges of PLA. 2012;27(4):187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khamechian T, Alizargar J, Mazoochi T. The Prevalence of Barrett's Esophagus in Outpatients with Dyspepsia in Shaheed Beheshti Hospital of Kashan. Iran J Med Sci. 2013;38(3):263–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sharifi A, Dowlatshahi S, Moradi Tabriz H, et al. The Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Correlates of Erosive Esophagitis and Barrett's Esophagus in Iranian Patients with Reflux Symptoms. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:696294. doi: 10.1155/2014/696294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azuma N, Endo T, Arimura Y, et al. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus and expression of mucin antigens detected by a panel of monoclonal antibodies in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(8):583–592. doi: 10.1007/s005350070057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi DW, Oh SN, Baek SJ, et al. Endoscopically observed lower esophageal capillary patterns. Korean J Intern Med. 2002;17(4):245–248. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2002.17.4.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Malekzadeh R, Sotoudeh M, et al. Lower esophagus in dyspeptic Iranian patients: a prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18(3):315–321. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hongo M, Shoji T. Epidemiology of reflux disease and CLE in East Asia. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(Suppl 15):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Shiba M, et al. Association between gastroesophageal flap valve, reflux esophagitis, Barrett's epithelium, and atrophic gastritis assessed by endoscopy in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(6):533–539. doi: 10.1007/s00535-002-1100-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khalaf AS. The efficacy of endoscopy: Analysis of its use in the evaluation of dyspeptic patients in Qatar. Emirates Medical Journal. 2003;21(2):134–138. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kawano T, Kouzu T, Ohara S, et al. The prevalence of Barrett's mucosa in the Japanese. Gastroenterological Endoscopy. 2005;47(4):951–961. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang W, Zhang ZJ, Lin KR, et al. [The prevalence, clinical and endoscopic characteristics of Barrett esophagus in Fujian] Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2006;45(5):393–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoo SS, Lee WH, Ha J, et al. [The prevalence of esophageal disorders in the subjects examined for health screening] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2007;50(5):306–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tseng PH, Lee YC, Chiu HM, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of Barrett's esophagus in a Chinese general population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(10):1074–1079. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31809e7126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yamagishi H, Koike T, Ohara S, et al. Tongue-like Barrett's esophagus is associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(26):4196–4203. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim JH, Hwang JK, Kim J, et al. Endoscopic findings around the gastroesophageal junction: an experience from a tertiary hospital in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2008;23(3):127–133. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2008.23.3.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Okita K, Amano Y, Takahashi Y, et al. Barrett's esophagus in Japanese patients: its prevalence, form, and elongation. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(12):928–934. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2261-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Park JJ, Kim JW, Kim HJ, et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for Barrett's esophagus in a Korean population: A nationwide multicenter prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(10):907–914. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318196bd11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shi X, Wang L, Hao H, et al. Study on reflux esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Chin J Gastroenterology. 2010;15(4):233–236. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zou D, He J, Ma X, et al. Epidemiology of symptom-defined gastroesophageal reflux disease and reflux esophagitis: the systematic investigation of gastrointestinal diseases in China (SILC) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(2):133–141. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.521888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fujimoto A, Hoteya S, Iizuka T, et al. Obesity and gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:760574. doi: 10.1155/2013/760574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watari J, Hori K, Toyoshima F, et al. Association between obesity and Barrett's esophagus in a Japanese population: a hospital-based, cross-sectional study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yin X, Xu Y-L, Zhou J, et al. Relationship among symptoms, endoscopic classification and pathological characteristics of Barrett esophagus. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Medical Science) 2013;33(1):50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, et al. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(6):1825–1831. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gerson LB, Edson R, Lavori PW, et al. Use of a simple symptom questionnaire to predict Barrett's esophagus in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(7):2005–2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Malfertheiner P, Lind T, Willich S, et al. Prognostic influence of Barrett's oesophagus and Helicobacter pylori infection on healing of erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and symptom resolution in non-erosive GORD: report from the ProGORD study. Gut. 2005;54(6):746–751. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.042143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1900–1920. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. quiz 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Harrison R, Perry I, Haddadin W, et al. Detection of intestinal metaplasia in Barrett's esophagus: an observational comparator study suggests the need for a minimum of eight biopsies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(6):1154–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O'Connor JB, Falk GW, Richter JE. The incidence of adenocarcinoma and dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus: report on the Cleveland Clinic Barrett's Esophagus Registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(8):2037–2042. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lao CD, Simmons M, Syngal S, et al. Dysplasia in Barrett esophagus. Cancer. 2004;100(8):1622–1627. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fan X, Snyder N. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in patients with or without GERD symptoms: role of race, age, and gender. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(3):572–577. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wani S. Population-based estimates of cancer and mortality in Barrett's esophagus: implications for the future. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(9):723–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rubenstein JH, Morgenstern H, Appelman H, et al. Prediction of Barrett's esophagus among men. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(3):353–362. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee YC, Cook MB, Bhatia S, et al. Interobserver reliability in the endoscopic diagnosis and grading of Barrett's esophagus: an Asian multinational study. Endoscopy. 2010;42(9):699–704. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cook MB, Wild CP, Forman D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the sex ratio for Barrett's esophagus, erosive reflux disease, and nonerosive reflux disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(11):1050–1061. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Andrici J, Tio M, Cox MR, et al. Hiatal hernia and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(3):415–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Andrici J, Cox MR, Eslick GD. Cigarette smoking and the risk of Barrett's esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(8):1258–1273. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cook MB, Greenwood DC, Hardie LJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the risk of increasing adiposity on Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(2):292–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Spechler SJ, Souza RF. Barrett's esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(9):836–845. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1314704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fischbach LA, Nordenstedt H, Kramer JR, et al. The association between Barrett's esophagus and Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2012;17(3):163–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00931.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shaheen NJ, Crosby MA, Bozymski EM, et al. Is there publication bias in the reporting of cancer risk in Barrett's esophagus? Gastroenterology. 2000;119(2):333–338. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.9302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goda K, Singh R, Oda I, et al. Current status of endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of superficial Barrett's adenocarcinoma in Asia-Pacific region. Dig Endosc. 2013;25(Suppl 2):146–150. doi: 10.1111/den.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.