Abstract

High steady-state reactive oxygen species (ROS) production has been implicated with metastatic disease progression. We provide new evidence that this increased intracellular ROS milieu uniquely predisposes metastatic tumor cells to hypoxia-mediated regulation of the matrix metalloproteinase MMP-1. Using a cell culture metastatic progression model we previous reported that steady-state intracellular H2O2 levels are elevated in highly metastatic 253J-BV bladder cancer cells compared to their non-metastatic 253J parental cells. 253J-BV cells display higher basal MMP-1 expression, which is further enhanced under hypoxic conditions (1% O2). This hypoxia-mediated MMP-1 increase was not observed in the non-metastatic 253J cells. Hypoxia-induced MMP-1 increases are accompanied by stabilization of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIF)-1α and HIF-2α, and a rise in intracellular ROS in metastatic 253J-BV cells. RNA interference studies show that hypoxia-mediated MMP-1 expression is primarily dependent on the presence of HIF-2α. Further, hypoxia promotes migration and spheroid outgrowth of only the metastatic 253J-BV cells and not the parental 253J cells. The observed HIF stabilization, MMP-1 expression and migration under hypoxia are dependent on increases in intracellular ROS, as these effects are attenuated by treatment with the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine. These data show that ROS play an important role in hypoxia-mediated MMP-1 expression and that an elevated intracellular redox environment, as observed in metastasis, predisposes tumor cells to an enhanced hypoxic response. It further supports the notion that metastatic tumor cells are uniquely able to utilize intracellular increases in ROS to drive pro-metastatic signaling events and highlights the important interplay between ROS and hypoxia in malignancy.

Keywords: Hypoxia, MMP-1, reactive oxygen species, H2O2, HIF-2α, metastatic bladder cancer

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide anion (O2•−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), are produced by various enzymatic and chemical processes within the cell. Tumor cells have been shown to display higher steady state ROS levels, which appear to further increase during metastatic progression.1–5 While NADPH oxidase enzymes are implicated in regulating ROS production in response to growth factors and cytokines, mitochondria serve as a major site of O2•− production as a result of electron leakage during the normal course of cellular respiration, and the one electron reduction of molecular oxygen (O2). O2•− is in turn spontaneously or enzymatically dismuted by manganese superoxide dismutase (Sod2) to the potent signaling oxidant H2O2. Increases in tumor cell ROS have been implicated with redox-dependent signaling pathways by regulating the activity of phosphatases, kinases and transcription factors.3,4,6–8 We and others have shown that steady-state increases in intracellular H2O2 control metastatic behavior, including invasion and migration.1,2,9, 10 These shifts in H2O2 also drive the expression of pro-metastatic proteins such as Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) family members.1,11 MMPs play an essential role in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling during morphogenesis, embryogenesis and wound healing, and their increased expression in cancer is associated with tumor angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis.12–15 In many cancers aberrant MMP-1 expression is observed in invasive disease and is associated with poor patient outcome.16–19 MMP-1 is an interstitial collagenase and member of the zinc-dependent endopeptidase family. It provides metastatic tumor cells the ability to clear the ECM and extravasate from the primary tumor tissue into the blood and lymph to colonize distant metastatic sites. MMP-1 activity is tightly controlled by proteolytic cleavage, including the negative regulation by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs), expression of which is often decreased in cancer. While transcription of MMP-1 is generally low in normal epithelia, it is enhanced in response to numerous stimuli, including growth factors, cytokines and hormones.20,21 In addition, exogenous sources of ROS, such as cigarette smoke and UV irradiation, have been shown to induce MMP-1 expression.22,23 We have previously demonstrated that increasing the intracellular redox environment of tumor cells can drive MMP-1 transcription via redox-mediated JNK and ERK1/2 signaling pathways and redox responsive elements on the MMP-1 promoter.24–26

Solid tumors commonly grow beyond the limits of oxygen diffusion and engage a hypoxic response to promote angiogenesis, invasion, epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), cancer stem-cell self-renewal and cell survival.27 The cellular response to hypoxia requires the induction of hypoxia inducible transcription factors (HIFs), comprising the oxygen labile α-subunits (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α) and a stable β-subunit. In normoxia, HIF-α is hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) in the presence of O2, Fe(II), 2-oxoglutarate and ascorbate. Hydroxylated HIF-α is then ubiquitylated via interaction with the von Hippel-Lindau (pVHL), resulting in subsequent degradation by the proteasome.28– 30 When O2 is limiting, HIF-α is not hydroxylated, and stabilizes to heterodimerize with HIF-1β. This complex binds hypoxic response elements (HRE) of promoters, activating transcription of genes involved in the regulation of erythropoiesis, glycolysis, angiogenesis, cell cycle, and survival. High HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression is associated with poor prognosis of a number of cancer types.31 Recent evidence suggests that HIF-1α has a dominant role in controlling responses to acute hypoxia, whereas HIF-2α drives the response to chronic low oxygen exposure and may be an important driver in tumorigenisis and metastatic progression.32,33

Hypoxia also increases mitochondrial ROS production, which contributes to the stabilization of HIFs.34,35 Complex III within the mitochondrial electron transport chain has been shown to be the major source of O2•− production in response to hypoxia.36–38 A number of mechanisms have been proposed that result in consequential HIF stabilization in response to ROS (and reactive nitrogen species), including oxidation of Fe(II)-bound PHD, the involvement of ROS-mediated fenton chemistry to shift the Fe(II) pool to Fe(III) thereby limiting PHD activity, S-nitrosylation, and redox-regulation of signaling pathways that either lead to PHD inactivation and transcriptional repression or HIF stabilization and transcriptional/translational activation.39–44 These reports all suggest that there is a strong interplay between ROS and hypoxia, yet it remains unknown if these two mechanisms converge to regulate expression of MMP-1 during metastatic progression. While ROS and hypoxia have separately been shown to enhance MMP-1 expression, it has previously not been established that hypoxia mediated MMP-1 expression is dependent on ROS.

We previously demonstrated that a progression to metastasis results in elevated levels of intracellular ROS in bladder cancer cells, and that metastatic cells are able to survive and utilize the endogenous increases in H2O2 to drive redox-dependent, pro-metastatic signaling.1,9 Given that metastatic tumor cells are often exposed to environmental conditions of low oxygen, we set out to investigate how increased steady-state ROS levels influence the response of metastatic tumor cells to hypoxia. Using a cell culture model of metastatic progression we found that an elevated steady-state redox milieu uniquely predisposes metastatic cancer cells to hypoxia-mediated MMP-1 regulation in a ROS-dependent manner.

Material and Methods

Cell culture, treatment and transfection

Non-metastatic 253J and the related metastatic variant cell line 253J-BV were maintained as described previously.1,9,45 Cells were pretreated in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS and 2 mmol/L N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC; Sigma-Aldrich) for 18 hours, followed by the same treatments in serum-free media for the duration of the experiments. Cells were treated with H2O2 (Sigma-Aldrich) in serum-free DMEM. For studies involving hypoxic conditions (1% O2), cells were incubated in a hypoxia chamber (ProOx C21, Biospherix) for 18 hours. GM6001 was purchased from Calbiochem and cells treated for 24 hours with 30 µM. siRNA was transfected for 24 hours using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and Dharmacon SMARTpool siRNAs for HIF-1α (ON-TARGETplus HIF-1α siRNA), HIF-2α (ON-TARGETplus HIF-2α siRNA), and non-targeting scramble siRNA.

RNA extraction and cDNA

Total RNA was extracted from bladder cancer cell lines using RNeasy mini Kit (Qiagen). The concentration of total RNA was measured using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and first strand cDNA synthesis of 1 µg total RNA carried out using iScrip™ cDNA Synthesis-Kit (Bio-Rad).

Real time PCR

Real time semi-quantitative RT-PCR was carried out on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR cycler, with the following primer pairs: HIF-1α, 5’-TGCTCATCAGTTGCCACTTCC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCAAATCACCAGCATCCAGAAGT-3’ (reverse); HIF-2α 5’-AGTGCATCATGTGTGTCAACTACG-3’ (forward) and 5’-GGGCTTGAACAGGGATTCAGTC-3’ (reverse); MMP-1, 5’-CCAAACCCACTCCACCTTAC-3’ (forward) and 5’-TCATCTTTCCCTTGCGGTA-3’ reverse); VEGF, 5’-GCTGCTCTACCTCCACCATGC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCATGAACTTCACCACTTCGTG-3’ (reverse); β-actin, 5’-CTCTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCCTG-3’ (forward) and 5’-CAGCACTGTGTTGGCGTACAG-3’ (reverse). The reaction components were mixed with 10 µl of SYBR master enzyme mix, 5µl of cDNA (10 ng/µl), 0.2 µl of each primer (10 µM) and 4.6 µl of nuclease free water. The reaction conditions were 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 59 °C for 30 s and 95°C for 15 s. The melting curves were analyzed from 60°C to 95°C with continuous fluorescence reading. Data were analyzed using the comparative CT method with values normalized to β-Actin levels and expressed relative to levels in untreated 253J cells.

Immunoblotting

To analyze secreted MMP-1 proteins in serum-free media, supernatants were harvested and concentrated 10-fold, using Amicon ultra-4 centrifugal filters. The protein amount of concentrated supernatant was determined using BCA reagent (Thermo Scientific). The supernatant (25 µg protein) was loaded on SDS-PAGE (4–12%, Bio-Rad) and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Following transfer, membranes were incubated with primary anti-MMP-1 antibody (Millipore) in TBS with 0.1% Tween 20 for overnight 4°C. For HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein analysis, cells were cultured under hypoxic conditions (1% O2) for 18 hours. Cells were immediately lysed in 2x SDS sample buffer and equal amounts loaded on SDS-PAGE (4–12%, Bio-Rad), followed by protein transfer and membranes were added with primary anti- HIF-1α or HIF-2α antibody (Cell signaling) in 5% nonfat dry milk/TBS with 0.1% Tween 20 for overnight 4°C. Following secondary antibody incubation blots were visualized using the SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Oxidation of 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) and MitoSOX

Intracellular oxidation of H2DCFDA to 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) was measured using flow cytometry. Adherent cells were trypsinized for 5 minutes, followed by addition of growth media to inactivate trypsin. Cells pelleted by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes were washed with PBS, followed by resuspension in growth media containing H2DCFDA (Life Technologies) for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark. Cells were collected by centrifugation and washed with PBS, followed by resuspension in 1% BSA/PBS. The samples were kept on ice in the dark for flow cytometric analysis. Cells were analyzed using an ImageStream (Amnis) imaging flow cytometer with a 488 nm laser to detect oxidized fluorescent DCF, and fluorescence intensities and images of at least 1000 single cells collected. Results represent average fluorescence intensity ± SEM. Mitochondrial O2•− was measured by assessing the oxidation and fluorescence of the MitoSOX Red dye (Life Technologies), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells seeded on glass bottom culture dish (MatTeK) were rinsed with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) and treated with 5µM MitoSOX Red dye for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark. Following gentle washing in HBSS cells stained with MitoSOX Red dye were examined using a Nikon Fluorescence Microscopy. 30–52 cells/image were analyzed and fluorescent intensities measured using ImageJ software, following background correction. Results were calculated as the average intensity of three images ± SEM, and experiments carried out in triplicate.

Wound healing assay

For analysis of migration, cells were trypsinized and 2 × 104 of cells were replated into IBIDI 35 mm µ-Dishes and cultured overnight to reach confluency. The next day, the inserts were removed to expose a cell free gap (“wound”), cells were washed with PBS and serum free media added. Migration was monitored by microscopy imaging at time 0 and 18 hours and the number of cells migrated into the wound counted.

Spheroid Formation and Outgrowth assays

Bladder cancer cell lines were seeded (1000 cells/well) into 96 well round bottom ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates (Corning) and allowed to form anchorage independent spheroid aggregate for 72 hours under normal culture conditions with fully supplemented media. 24-well plates were coated overnight at 37°C with 5 µg/ml type I collagen, type IV collagen and fibronectin in PBS. The spheroids were added to each of the coated wells under normoxia or hypoxia and the movement of cells escaping from the spheroid into the surrounding ECM proteins monitored over 18 hrs. This was quantified as percentage change in the area covered by tumor cells using Image J software.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean +/− SEM from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA for multiple comparisons or T-tests for 2 group analysis with normal distribution, using Prism 6 (GraphPad software)

Results

Hypoxia drives MMP-1 transcription in metastatic cancer cells with high intracellular steady-state ROS

In the present study we used a bladder cancer metastatic progression model to assess the interplay between hypoxia and ROS on MMP-1 expression and metastasis. This model was first described by Dinney et al., who derived a highly metastatic cell line (253J-BV) from a human bladder adenocarcinoma parental cell line (253J-P), following five successive orthotopic transplantations into the bladder wall of nude mice.45 Using a redox sensitive mitochondria-targeted GFP probe (RoGFP) and by directly measuring intracellular H2O2 levels biochemically, we previously demonstrated that the highly metastatic bladder cancer cell line 253J-BV displays higher steady state intracellular ROS levels compared to the related non-metastatic parental variant 253J (Steady state H2O2 levels: 253J: 18.09+/−4.07 pM; 253J-BV: 31.08 +/−0.29 pM).1 253J-BV cells also exhibited alterations in their antioxidant enzyme levels, with high manganese superoxide dismutase (Sod2) and low catalase expression, which we believe enhances the high steady-state H2O2 phenotype in these cells.1 As a consequence, 253J-BV cells displayed high redox-dependent MMP-9 and VEGF expression, and increased migration and invasion compared to the parental 253J line.1,9 Moreover, we demonstrated that forced expression of Sod2 and increased steady-state ROS levels induce transcription of MMP-1 in fibrosarcoma HT-1080 cells.24,25,46 In agreement with these findings, 253J-BV cells with higher steady-state redox status displayed significantly higher MMP-1 mRNA levels than 253J cells under normoxic (21% O2) conditions in the present study (Fig. 1A). We assessed if this difference in steady-state redox status influences the response of metastatic tumor cells to hypoxia, by monitoring the effects of low oxygen on transcription of the pro-metastatic genes MMP-1 and VEGF. Interestingly, exposure of cells to hypoxia (1% O2) further increased MMP-1 expression, however this effect was primarily observed in the metastatic 253J-BV cells, which display higher steady-state H2O2 levels. MMP-1 expression in response to hypoxia was also demonstrated in other aggressive bladder cancer cell lines, with the highest increases observed in the highly tumorigenic HT1197 cell line, while the less aggressive RT4 and T24 displayed lower or no significant changes in MMP-1 levels, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1A). These data suggest that the hypoxic regulation of MMP-1 is coincident with the acquisition of the malignant phenotype and may be dependent on the intracellular redox threshold of tumor cells.

Figure 1. Hypoxia induces transcription of MMP-1 in metastatic 253J-BV cells, but not in the non-metastatic parental cell line 253J.

A Expression of MMP-1 is increased only in 253J-BV cells following exposure to hypoxia (H, 1% O2 for 18 hrs; N=normoxia, 21%O2), as assessed by semi-quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis. B. Expression analysis of VEGF in response to hypoxia in 253J and 253J-BV cells Fold-increases in mRNA levels are expressed relative to normoxic culture conditions. (A & B: n=3, Average ±SEM; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ANOVA, with Tukey’s post-test).

Hypoxia-regulated MMP-1 transcription is ROS-dependent

Based on the previously established interplay between hypoxia and ROS, we next investigated whether hypoxia modulates MMP-1 expression in a ROS-dependent manner. Treatment of hypoxic cells with the antioxidant NAC significantly decreased mRNA level of MMP-1 in 253J-BV cells, but had no effect on MMP-1 levels in 253J cells under both normoxic (21% O2) and hypoxic (1% O2) conditions (Fig. 2A). Similarly, hypoxia-mediated MMP-1 expression of HT1197 was also redox-dependent, while this was not observed in the non-invasive RT4 cell line (Supplementary Figure S1B). Hypoxia-driven VEGF mRNA increases were also significantly impaired by administration of the antioxidant NAC (Fig. 2B). We next assessed if the metastasis-specific hypoxia-mediated increase in MMP-1 mRNA translates to higher MMP-1 protein expression. Indeed, exposure of 253J-BV cells to 1% O2 significantly increased MMP-1 protein excretion into the media and this was attenuated following treatment with NAC, suggesting a redox-dependent regulatory mechanism (Fig. 2C and D). Again, this increase in MMP-1 protein was only observed in 253J-BV cells. The oxidation of the redox-sensitive dye H2DCFDA was also enhanced in 253J-BV cells under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3A and B), and fluorescence of the mitochondria-targeted redox sensor MitoSOX was similarly increased in response to hypoxia (Fig. 3C and D). These data suggest that hypoxic ROS generation selectively drives MMP-1 transcription in metastatic tumor cells.

Figure 2. Antioxidant treatment attenuates hypoxia-mediated MMP-1 RNA and protein expression in metastatic 253J-BV cells.

MMP-1 (A) and VEGF (B) mRNA levels are increased in 253J-BV cells exposed to hypoxia (H, 1% O2) for 18 hrs, which is abrogated by treatment with the antioxidant NAC (2 mmol/L). C. Hypoxia-mediated MMP-1 protein expression is ROS-dependent. Excreted MMP-1 protein was detected by western blotting as described in methods and the increased MMP-1 expression in 253J-BV cells in response to hypoxia (% O2, 18 hrs) was abrogated following incubation with the antioxidant NAC. D. Quantification of MMP-1 protein levels normalized to actin. (A, B & D: n=3, Average ±SEM; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ANOVA with Tukey’s post test).

Figure 3. DCF and MitoSOX fluorescence is enhanced in metastatic 253J-BV cells in response to hypoxia.

A Levels of DCF fluorescence in 253J-BV were assessed by Image stream flow cytometry of cells exposed to normoxia (N, 21% O2), hypoxia (H, 1% O2) and H2O2 (500µM; scale bar: 10µm). B. Mean fluorescence intensity of DCF from an average of 5000 cells per treatment group is shown from one representative experiment of triplicate repeats (Average ±SEM; ****p<0.0001, ANOVA with Dunnett post-test, compared to normoxia). C. MitoSOX Red fluorescence in 253J and 253J-BV was assessed in live cells following exposure to 18 hrs of normoxia (N, 21% O2) or hypoxia (H, 1% O2), with or without the addition of the superoxide scavenger MitoTEMPO (60µM; scale bar: 100µm). D. Average Fluorescence per field (n=30–50 cells) was quantified using ImageJ (n=3, Average ±SEM; *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001, ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test). One replicate of three independent experiments is shown.

Inhibition of HIF-2α attenuates hypoxia-mediated MMP-1 transcription

HIF-1α and HIF-2α silencing RNAi was used to determine whether the hypoxia-mediated redox-regulation of MMP-1 is attributed to HIF transcription factors. Of the two transcription factors, abrogation of HIF-2α expression significantly decreases both MMP-1 and VEGF levels in 253J-BV cells in response to hypoxia (Fig. 4A and B). HIF-1α knockdown only slightly decreased MMP-1 and VEGF mRNA levels, with double knockdown of HIF-1α and HIF-2α having an additive effect in reducing the hypoxic expression of both genes in 253J-BV cells. Knockdown of HIF-1α and HIF-2α did not affect levels of MMP-1 in non-metastatic 253J cells under normoxia or hypoxia (Fig. 4). These findings suggest that HIF-2α is predominantly involved in the hypoxic induction of MMP-1 in metastatic bladder cancer cells. Although not statistically significant, a consistent trend in decreased MMP-1 and VEGF mRNA levels was observed when HIF-1α and HIF-2α were knocked down in 253J-BV cells at 21% O2, suggesting that the enhanced steady-state redox environment of the metastatic cells may contribute to HIF-dependent regulation of MMP-1 and VEGF even under normoxia.

Figure 4. Inhibition of HIF-2α expression decreases MMP1 and VEGF mRNA transcription in response to hypoxia in 253J-BV cells.

Increased MMP-1 (A) and VEGF (B) mRNA level in hypoxia were attenuated by suppression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression using siRNA. mRNA expression was monitored using semi-quantitative realtime RT-PCR as described in Methods. Specificity of siRNA towards either HIF-1α or HIF-2α was demonstrated by monitoring HIF levels using semi-quantitative real-time RT-PCR (C & D). All data are expressed as fold-increases in mRNA levels relative to scramble control (S) in normoxic culture conditions. (A-D: M=mock transfected controls, n=3, Average ±SEM; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ANOVA with Tukey’s post test).

Hypoxia-mediated HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein stabilization is ROS-dependent in metastatic 253J-BV cells

We next determined whether hypoxia-induced HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein stabilization is ROS dependent in our model. Even under normoxic conditions 253J-BV cells display increased HIF-1α protein levels compared to 253J cells and these were decreased following treatment with NAC, suggesting that the increased steady-state redox status enhances the stability of HIF-1α in metastatic cells (Fig. 5A and B). HIF-2α protein levels were undetectable in both cell lines cultured under 21% O2 (Fig. 5A and C). However, in response to hypoxia both HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein levels were markedly increased in 253J-BV cells, with only modest changes observed in the non-metastatic variant 253J (Fig. 5A–C). Treatment with the antioxidant NAC showed that both HIF-1α and HIF-2α stabilization in response to 1% O2 is at least in part ROS-dependent in metastatic 253J-BV cells (Fig. 5A–C). The redox dependent effect on HIF-1α and HIF-2α levels under hypoxia was specific to protein stabilization. Although HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA level were higher in 253J-BV cells compared with 253J cells in 21% O2 conditions, hypoxia and antioxidant treatment did not alter mRNA levels in either cell line (Fig. 5D and E). These data indicate that the ROS-dependent effects of hypoxia are elicited at the level of HIF protein stabilization.

Figure 5. HIF protein stabilization in response to hypoxia is redox-dependent in 253J-BV cells.

A Exposure of cells to hypoxia (H) leads to HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein stabilization as assessed by immunoblotting. Quantification of HIF-1α (B) and HIF-2α (C) protein levels, shows that HIF stabilization is significantly enhanced in metastatic 253J-BV cells and redox dependent, as NAC treatment (2mmol/L) was able to decrease HIF-1α and HIF-2α stabilization in 253J-BV cells under hypoxia. NAC treatment does no influence transcriptional regulation of HIFs as assessed by semi-quantitative real-time RT-PCR. While HIF-1α (D) and HIF-2α (E) mRNA levels are higher in 253J-BV cells under normoxia (N) compared to 253J cells, there were no significant changes in levels following 18hrs of hypoxia or NAC treatment. All data are expressed as fold-increases in mRNA or protein levels relative to normoxia. (B-E: n=3, Average ±SEM; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ANOVA with Tukey’s post test).

Hypoxia enhances migration and spheroid outgrowth in a redox-dependent manner

Cell migration and spheroid outgrowth were assessed to elucidate the consequences of hypoxia on 253J-BV metastatic behavior. We previously demonstrated that metastatic 253J-BV cells migrate at a faster rate than 253J cells under normoxia.9 The rate of 253J-BV migration was further enhanced when wound-healing assays were performed under 1% O2 conditions (Fig. 6A). To mimic metastatic spread of cells from micro-metastases, cells were cultured as anchorage independent spheroids and metastatic spread of cells monitored by placing the spheroid on ECM components. 253J-BV cells exhibited enhanced migration from the attached spheroid on collagen I and IV under hypoxia when compared with normoxic conditions (Fig. 6B). The effects were most pronounced on collagen I, a preferred substrate of MMP-1.

Figure 6. Metastatic 253J-BV cells exhibit enhanced migration and spheroid metastatic spread in response to hypoxia.

A Exposure of cells to hypoxia increased migration of metastatic 253J-BV cell in a wound healing assay. B. Hypoxia increases tumor spheroid outgrowth on MMP-1 ECM substrates. 253J-BV cells were grown as spheres in ULA plates as indicated in methods and seeded in 24 well plates coated with ECM components collagen I, collagen IV and fibronectin. Migration of cells was monitored under conditions of normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2) and metastatic spread measured as the area covered by migrating cells after 24 hours. (A-B: n=3, Average ±SEM; *p<0.05, Student’s T-test).

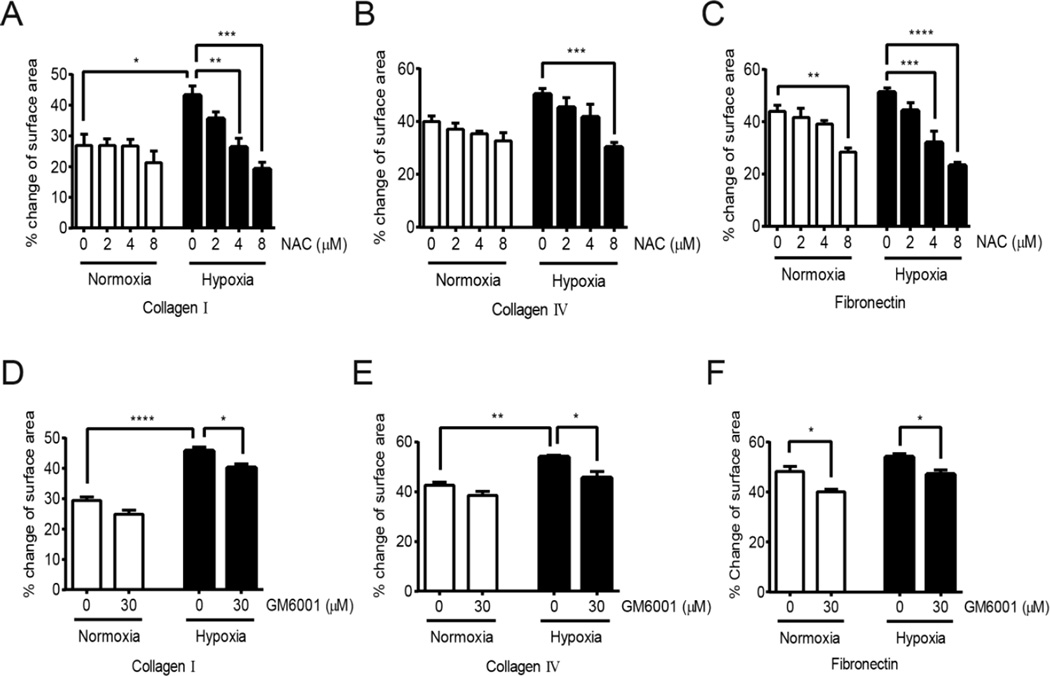

To assess if the enhanced migration and spheroid outgrowth on ECM components is dependent on the alterations of cellular redox status in response to hypoxia, outgrowth of cells from spheroids was monitored under increasing doses of the antioxidant NAC (Fig. 7 A–C). Treatment of 253J-BV cells with NAC significantly decreased spheroid metastatic spread, suggesting that the migration of cells on ECM components under hypoxia is redox-dependent (Fig. 7A–C). To demonstrate that this effect is reliant on the induction of ECM-degrading enzymes, the MMP inhibitor GM6001 was used and shown to significantly abrogate cellular spread from the spheroids on ECM components under hypoxic conditions, while this effect was less pronounced under normoxia (Fig. 7D–F). These finding suggest that hypoxia-induced redox-regulation of MMP-1 expression exacerbates the metastatic phenotype of metastatic tumor cells.

Figure 7. Hypoxia-induced spheroid metastatic spread is abrogated by antioxidant and MMP inhibitor treatment.

253J-BV spheres were culture in ULA plates as described in methods and seeded on collagen I, collagen IV and fibronectin coated wells and outgrowth monitored under normoxia or hypoxia for 24 hours, with or without indicated doses of NAC (A-C) or MMP inhibitor (GM6001; D-F). Metastatic spread was measured by the area covered by migrating cells after 24 hours. (A-F: n=3, Average ±SEM; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ANOVA with Tukey’s post test).

Discussion

Metastatic disease progression is accompanied by cellular changes that include EMT induction, regulation of pro-migratory signaling and alterations in gene transcription. In addition, metastatic tumor cells are susceptible to hypoxia and changes in both extracellular and intracellular ROS. We have previously shown that the metastatic 253J-BV bladder cancer cells exhibit endogenous increases in intracellular ROS compared to a related non-metastatic parental 253J cell line.1 This enhanced redox status contributed to increased MMP-9 and VEGF expression and was able to augment the clonogenicity, and migratory and invasive behavior of 253J-BV cells.1, 9 Mechanistically, increases in steady-state H2O2 level were shown to regulate cellular signaling by oxidation of key phosphatases involved in focal adhesion kinase signaling, including PTPN12 and PTEN.9,47

A number of labs have demonstrated the interplay between ROS and hypoxia. Chandel et al. have shown that hypoxia promotes an increase in mitochondrial ROS production, resulting in PHD inhibition and stabilization of HIF-1α.34–36 Our findings indicate that metastatic tumor cells distinctively respond to hypoxia in a redox-dependent manner and show for the first time that these two mechanisms converge to regulate the expression of MMP-1. Unlike the non-metastatic parental cells 253J, only metastatic 253J-BV cells display a redox-dependent increase in MMP-1 in response to hypoxia, which promotes migration and spheroid outgrowth (Fig. 6). We show that stabilization of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α is significantly enhanced in a redox-dependent manner under low oxygen (Fig. 4), and that HIF-2α may be primarily responsible for MMP-1 regulation in this context (Fig. 5). Our data suggest that a pre-existing higher steady-state intracellular ROS level, as observed in 253J-BV cells1, is necessary to reach the threshold for ROS- dependent HIF stabilization and subsequent MMP-1 induction in response to hypoxia. An altered intracellular redox milieu may therefore specifically pre-dispose metastatic tumor cells to an enhanced hypoxic response, exacerbating their metastatic phenotype. The novel finding that metastatic cells with an increased cellular ROS milieu are more susceptible to this mode of MMP-1 regulation further highlights the important interplay between ROS and hypoxia in metastatic cancer progression.

We have previously demonstrated that subtle increases in the intracellular redox environment of cells contribute to the transcriptional regulation of MMP-1. Using a model where steady state levels of H2O2 were enhanced by overexpression of the mitochondrial superoxide dismutase Sod2, we were able to demonstrate that MMP-1 redox-regulation occurs through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, JNK and ERK1/2, that result in transcriptional regulation of redox-sensitive elements of the MMP-1 promoter.24–26, 46 In the present manuscript we show for the first time that hypoxia and ROS converge to drive aberrant MMP-1 in metastatic tumor cells. While other studies have not linked ROS to the regulation of MMP-1 under low O2, it has been reported that MMP-1 transcription is regulated by hypoxia.48–51 Interestingly, a recent report shows that there may be a feed-back mechanism between MMP-1 and HIF regulation. In human alveolar epithelial cells MMP-1 expression is enhanced in response to hypoxia and enforced expression of MMP-1 can in turn enhance HIF1-α protein levels.52 Unlike some other hypoxia-responsive genes, regulation of MMP-1 appears to require prolonged exposure to low O2.50 While HIF-1α has been implicated in MMP-1 regulation49, some studies have found that this regulation is elicited in a HIF-1α-independent manner. It was found that CREB and NF-κB, as well as HIF-2α, are involved in hypoxia-mediated induction of MMP-1 48,50,51 This is consistent with our results showing that HIF-2α knockdown more effectively attenuated MMP-1 expression rather than HIF-1α loss (Fig. 4).

While both HIF-1α and HIF-2α are expressed in various tumor types and their increased expression associated with tumor aggressiveness, angiogenesis and poor patient prognosis, HIF-2α has been implicated as a more important driver of tumor development, invasion and is associated with tumor stem cells.32,33,53–57 One suggested mechanism for HIF-2α specific regulation in this context is the differential regulation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α by the hypoxia associated factor (HAF) protein. Increased HAF levels have been detected in various tumor types and it appears to play an important role in hypoxia signaling by turning on the HIF-2α response under prolonged hypoxia.58 Although we did not observe any change in HAF mRNA and protein levels in 253J-BV cells during hypoxic exposure, we detected higher basal expression of HAF protein in 253J-BV cells compared with 253J cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). While this increased HAF expression in metastatic 253J-BV cells was not significantly abrogated following NAC treatment, we are further investigating if the enhanced redox environment of 253J-BV cells contributes to enhanced HAF expression.

We previously demonstrated that 253J-BV cells display increased steady state H2O2 levels and increased mitochondrial oxidation of the redox sensitive roGFP probe1, suggesting that mitochondrial steady-state redox tone may be responsible for redox-dependent HIF stabilization and expression of MMP-1 under hypoxia. While we demonstrated increased oxidation of the mitochondria targeted probe MitoSOX in 253J-BV cells in response to hypoxia, addition of the O2•− scavenger MitoTEMPO only slightly decreased the oxidation of this dye (Fig. 3C and D), making it difficult to conclude whether increases in O2•− are directly generated as a consequence of hypoxia. Unlike NAC, MitoTEMPO failed to inhibit MMP-1 expression increases in response to hypoxia (Supplementary Fig. S3). While further experimental evidence is required, these data suggest that the effects of hypoxia on MMP-1 expression cannot simply be attributed to changes in mitochondrial O2•− production. Instead, it is likely that mitochondria generated ROS and concomitant redox reactions, including the generation of secondary reactive species, including H2O2 and •OH and the oxidation of mitochondrial and cytoplasmic proteins, contribute to an altered cellular redox state that influences HIF stabilization and MMP-1 expression. This may also explain the observation that the glutathione precursor NAC consistently abrogates hypoxia-induced MMP-1 expression. The stabilization of HIF proteins in response to hypoxia-generated ROS has been attributed to various processes including PHD inhibition, where Fe(II) oxidation to Fe(III) limits Fe(II) availability for maximal PHD activity40,41 In addition, HIF-2α can be regulated by the redox-sensitive deacetylase Situin-1, and it has been demonstrated that NADPH oxidase (NOX)-derived ROS enhances HIF-2α mRNA translation, as a consequence of redox regulation of mTORC2.43,59 Interestingly, the ROS-mediated protein stabilization of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in response to hypoxia was specifically observed in 253J-BV cells and not in 253J cells (Fig. 5), again suggesting that higher steady-state ROS levels are necessary to reach the threshold for ROS-dependent HIF activation in response to hypoxia. Further, abrogation of hypoxia-mediated HIF stabilization, MMP-1 transcription and 253J-BV migration by NAC show that changing the redox status of metastatic tumor cells can influence their response to hypoxia and prevent metastatic behavior. This supports previous work demonstrating that NAC elicits its main anti-tumor effects by preventing HIF stabilization.60

In summary, the current study establishes a redox-dependent link to the hypoxia-mediated induction of MMP-1 expression, which accentuates the metastatic phenotype of bladder cancer cells. Our data suggest that this may be associated with the pre-existing increase in in the steady-state redox balance of metastatic tumor cells. Thus, the intracellular redox status needs to be taken into consideration when assessing the effects of hypoxia on cells, as well as in the development of treatment strategies for metastatic disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

-

Hypoxia specifically regulates MMP-1 transcription in metastatic bladder cancer cells, which display elevated steady-state H2O2 levels.

-

-

Hypoxia-regulated MMP-1 transcription is reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent.

-

-

Hypoxia-mediated HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein stabilization is ROS-dependent, and inhibition of HIF-2α attenuates hypoxia-mediated MMP-1 transcription in metastatic bladder cancer cells.

-

-

Hypoxia enhances migration and spheroid metastatic spread of cells in a ROS-dependent manner.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Badar Mian (Albany Medical College) and Colin Dinney (M.D. Anderson Cancer Center) for generously providing 253J and 253J-BV cell lines, and Dr. David Degraff (Penn State Hershey College of Medicine) for T24, RT4, and HT1197 bladder cancer cell lines. We are grateful to Dr. Fatima Mechta-Grigoriou (Institute Curie) for helpful discussion. We thank Mr. James Iuliano and Jeffrey Richards for helpful technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant R00CA143229 (to N. Hempel).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hempel N, Ye H, Abessi B, Mian B, Melendez JA. Altered redox status accompanies progression to metastatic human bladder cancer. Free radical biology & medicine. 2009;46:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishikawa K, Takenaga K, Akimoto M, Koshikawa N, Yamaguchi A, Imanishi H, et al. ROS-generating mitochondrial DNA mutations can regulate tumor cell metastasis. Science. 2008;320:661–664. doi: 10.1126/science.1156906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishikawa M. Reactive oxygen species in tumor metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu WS. The signaling mechanism of ROS in tumor progression. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2006;25:695–705. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szatrowski TP, Nathan CF. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer research. 1991;51:794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamanaka RB, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulate cellular signaling and dictate biological outcomes. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2010;35:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forman HJ, Maiorino M, Ursini F. Signaling functions of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry. 2010;49:835–842. doi: 10.1021/bi9020378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulsen CE, Carroll KS. Orchestrating redox signaling networks through regulatory cysteine switches. ACS chemical biology. 2010;5:47–62. doi: 10.1021/cb900258z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hempel N, Bartling TR, Mian B, Melendez JA. Acquisition of the metastatic phenotype is accompanied by H2O2-dependent activation of the p130Cas signaling complex. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2013;11:303–312. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinberg F, Chandel NS. Reactive oxygen species-dependent signaling regulates cancer. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2009;66:3663–3673. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0099-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connor KM, Subbaram S, Regan KJ, Nelson KK, Mazurkiewicz JE, Bartholomew PJ, et al. Mitochondrial H2O2 regulates the angiogenic phenotype via PTEN oxidation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:16916–16924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang C, Werb Z. The many faces of metalloproteases: cell growth, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis. Trends in cell biology. 2001;11:S37–S43. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02122-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sternlicht MD, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vu TH, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: effectors of development and normal physiology. Genes & development. 2000;14:2123–2133. doi: 10.1101/gad.815400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagase H, Visse R, Murphy G. Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovascular research. 2006;69:562–573. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang X, Dutton CM, Qi WN, Block JA, Garamszegi N, Scully SP. siRNA mediated inhibition of MMP-1 reduces invasive potential of a human chondrosarcoma cell line. Journal of cellular physiology. 2005;202:723–730. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray GI, Duncan ME, O’Neil P, McKay JA, Melvin WT, Fothergill JE. Matrix metalloproteinase-1 is associated with poor prognosis in oesophageal cancer. The Journal of pathology. 1998;185:256–261. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199807)185:3<256::AID-PATH115>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bostrom P, Soderstrom M, Vahlberg T, Soderstrom KO, Roberts PJ, Carpen O, et al. MMP-1 expression has an independent prognostic value in breast cancer. BMC cancer. 2011;11:348. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sunami E, Tsuno N, Osada T, Saito S, Kitayama J, Tomozawa S, et al. MMP-1 is a prognostic marker for hematogenous metastasis of colorectal cancer. The oncologist. 2000;5:108–114. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-2-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincenti MP, Brinckerhoff CE. Transcriptional regulation of collagenase (MMP-1, MMP-13) genes in arthritis: integration of complex signaling pathways for the recruitment of gene-specific transcription factors. Arthritis research. 2002;4:157–164. doi: 10.1186/ar401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westermarck J, Kahari VM. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression in tumor invasion. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1999;13:781–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercer BA, Kolesnikova N, Sonett J, D’Armiento J. Extracellular regulated kinase/mitogen activated protein kinase is up-regulated in pulmonary emphysema and mediates matrix metalloproteinase-1 induction by cigarette smoke. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:17690–17696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenneisen P, Sies H, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Ultraviolet-B irradiation and matrix metalloproteinases: from induction via signaling to initial events. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2002;973:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson KK, Subbaram S, Connor KM, Dasgupta J, Ha XF, Meng TC, et al. Redox-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression is regulated by JNK through Ets and AP-1 promoter motifs. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:14100–14110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601820200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson KK, Ranganathan AC, Mansouri J, Rodriguez AM, Providence KM, Rutter JL, et al. Elevated sod2 activity augments matrix metalloproteinase expression: evidence for the involvement of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in regulating metastasis. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;9:424–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranganathan AC, Nelson KK, Rodriguez AM, Kim KH, Tower GB, Rutter JL, et al. Manganese superoxide dismutase signals matrix metalloproteinase expression via H2O2-dependent ERK1/2 activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:14264–14270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris AL. Hypoxia--a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nature reviews Cancer. 2002;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohh M, Park CW, Ivan M, Hoffman MA, Kim TY, Huang LE, et al. Ubiquitination of hypoxia-inducible factor requires direct binding to the beta-domain of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Nature cell biology. 2000;2:423–427. doi: 10.1038/35017054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, Kim W, Valiando J, Ohh M, et al. HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science. 2001;292:464–468. doi: 10.1126/science.1059817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lando D, Peet DJ, Whelan DA, Gorman JJ, Whitelaw ML. Asparagine hydroxylation of the HIF transactivation domain a hypoxic switch. Science. 2002;295:858–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1068592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordan JD, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors: central regulators of the tumor phenotype. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2007;17:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmquist-Mengelbier L, Fredlund E, Lofstedt T, Noguera R, Navarro S, Nilsson H, et al. Recruitment of HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha to common target genes is differentially regulated in neuroblastoma: HIF-2alpha promotes an aggressive phenotype. Cancer cell. 2006;10:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franovic A, Holterman CE, Payette J, Lee S. Human cancers converge at the HIF-2alpha oncogenic axis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:21306–21311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906432106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandel NS, Maltepe E, Goldwasser E, Mathieu CE, Simon MC, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:11715–11720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell EL, Emerling BM, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial regulation of oxygen sensing. Mitochondrion. 2005;5:322–332. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandel NS, McClintock DS, Feliciano CE, Wood TM, Melendez JA, Rodriguez AM, et al. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:25130–25138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001914200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guzy RD, Hoyos B, Robin E, Chen H, Liu L, Mansfield KD, et al. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell metabolism. 2005;1:401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell EL, Klimova TA, Eisenbart J, Moraes CT, Murphy MP, Budinger GR, et al. The Qo site of the mitochondrial complex III is required for the transduction of hypoxic signaling via reactive oxygen species production. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;177:1029–1036. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emerling BM, Platanias LC, Black E, Nebreda AR, Davis RJ, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for hypoxia signaling. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:4853–4862. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.4853-4862.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gerald D, Berra E, Frapart YM, Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, Mansuy D, et al. JunD reduces tumor angiogenesis by protecting cells from oxidative stress. Cell. 2004;118:781–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan Y, Mansfield KD, Bertozzi CC, Rudenko V, Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, et al. Multiple factors affecting cellular redox status and energy metabolism modulate hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase activity in vivo and in vitro. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:912–925. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01223-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yasinska IM, Sumbayev VV. S-nitrosation of Cys-800 of HIF-1alpha protein activates its interaction with p300 and stimulates its transcriptional activity. FEBS letters. 2003;549:105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00807-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Block K, Gorin Y, Hoover P, Williams P, Chelmicki T, Clark RA, et al. NAD(P)H oxidases regulate HIF-2alpha protein expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:8019–8026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dioum EM, Chen R, Alexander MS, Zhang Q, Hogg RT, Gerard RD, et al. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha signaling by the stress-responsive deacetylase sirtuin 1. Science. 2009;324:1289–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.1169956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dinney CP, Fishbeck R, Singh RK, Eve B, Pathak S, Brown N, et al. Isolation and characterization of metastatic variants from human transitional cell carcinoma passaged by orthotopic implantation in athymic nude mice. The Journal of urology. 1995;154:1532–1538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Connor KM, Hempel N, Nelson KK, Dabiri G, Gamarra A, Belarmino J, et al. Manganese superoxide dismutase enhances the invasive and migratory activity of tumor cells. Cancer research. 2007;67:10260–10267. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hempel N, Melendez JA. Intracellular redox status controls membrane localization of pro- and anti-migratory signaling molecules. Redox biology. 2014;2:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ben-Yosef Y, Lahat N, Shapiro S, Bitterman H, Miller A. Regulation of endothelial matrix metalloproteinase-2 by hypoxia/reoxygenation. Circulation research. 2002;90:784–791. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000015588.70132.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin JL, Wang MJ, Lee D, Liang CC, Lin S. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha regulates matrix metalloproteinase-1 activity in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. FEBS letters. 2008;582:2615–2619. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakayama K. cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) and NF-kappaB transcription factors are activated during prolonged hypoxia and cooperatively regulate the induction of matrix metalloproteinase MMP1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:22584–22595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.421636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang S, Kim J, Ryu JH, Oh H, Chun CH, Kim BJ, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha is a catabolic regulator of osteoarthritic cartilage destruction. Nature medicine. 2010;16:687–693. doi: 10.1038/nm.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herrera I, Cisneros J, Maldonado M, Ramirez R, Ortiz-Quintero B, Anso E, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 induces lung alveolar epithelial cell migration and proliferation, protects from apoptosis, and represses mitochondrial oxygen consumption. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:25964–25975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.459784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Z, Bao S, Wu Q, Wang H, Eyler C, Sathornsumetee S, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer cell. 2009;15:501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qing G, Simon MC. Hypoxia inducible factor-2alpha: a critical mediator of aggressive tumor phenotypes. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2009;19:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kondo K, Kim WY, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG., Jr Inhibition of HIF2alpha is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS biology. 2003;1:E83. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, et al. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim WY, Perera S, Zhou B, Carretero J, Yeh JJ, Heathcote SA, et al. HIF2alpha cooperates with RAS to promote lung tumorigenesis in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:2160–2170. doi: 10.1172/JCI38443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koh MY, Lemos R, Jr, Liu X, Powis G. The hypoxia-associated factor switches cells from HIF-1alpha- to HIF-2alpha-dependent signaling promoting stem cell characteristics, aggressive tumor growth and invasion. Cancer research. 2011;71:4015–4027. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nayak BK, Feliers D, Sudarshan S, Friedrichs WE, Day RT, New DD, et al. Stabilization of HIF-2alpha through redox regulation of mTORC2 activation and initiation of mRNA translation. Oncogene. 2013;32:3147–3155. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao P, Zhang H, Dinavahi R, Li F, Xiang Y, Raman V, et al. HIF-dependent antitumorigenic effect of antioxidants in vivo. Cancer cell. 2007;12:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.