Abstract

Recent advances in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) therapeutics include novel medical, surgical, and endoscopic treatments. Among these, stem cell therapy is still in its infancy, though multiple studies suggest the immunomodulatory effect of stem cell therapy may reduce inflammation and tissue injury in IBD patients. This review discusses the novel avenue of stem cell therapy and its potential role in the management of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. We conducted a comprehensive literature search to identify studies examining the role of stem cell therapy (without conditioning and immunomodulatory regimens) in IBD. Taken together these studies suggest a promising role for SCT in IBD, although the substantial challenges, such as cost and inadequate/incomplete characterization of effect limit their current use in clinical practice.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Mesenchymal stem cells, Systematic review and meta-analysis, adverse effects, efficacy

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) which comprises of Ulcerative Colitis (UC) and Crohn’s Disease (CD), is presumed to result from an inappropriate response of the host’s immune system to intestinal microbes 1. The existing management strategies for IBD therefore target inflammation and include immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids, azathioprine, 6 mercaptopurine (6-MP), monoclonal antibodies against cytokine tumour necrosis factor alpha (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol and golimumab), the recently approved integrin inhibitor Vedolizumab (anti-α4β7 Integrin), and surgery 2–13. A recent study of monotherapy versus combination therapy in UC patients showed induction of clinical remission (defined as a total Mayo score of 2 points or less, with no individual subscore exceeding 1 point, without the use of corticosteroids) in 23.7% by azathioprine, in 22.1% by infliximab and in only 39.7% of patients by combination therapy at 16 weeks 14. Thus, approximately 60% of UC patients failed to achieve clinical remission at 16 weeks even with combination therapy. Similarly, the SONIC study (Study of Biologic and Immunomodulator Naive Patients in Crohn’s Disease) for CD patients, showed induction of clinical remission in 30% of patients by azathioprine, in 44.4% by infliximab and in 56.8% of patients by combination therapy at 26 weeks. Therefore, combination therapy fails to achieve clinical remission in 43% of patients at the end of 26 weeks 15. In addition, use of these immunosuppressive medications is associated with risk of adverse events like serious infections 16, neurological disorders 17 and malignancies 18. Thus, there is a need for novel and new therapies to treat IBD.

Over the last three decades, tremendous progress has been made in the field of regenerative medicine and stem cell biology 19. Stem cells are a unique group of undifferentiated cells that have capacity of self-renewal, and under certain physiological or experimental conditions possess the ability to become organ or tissue specific cells with differentiated function 20. In addition to their regenerative properties, a type of stem cells called multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) have unique immunoregulatory/suppressive properties that are currently being investigated as a treatment option for inflammatory disorders. In this study, we perform a systematic review of adverse events and efficacy of MSC’s for treatment of IBD. In order to provide relevant context, we briefly describe different types of stem cells, and their putative in-vitro and in-vivo mechanisms of immunoregulation.

Stem cells can be broadly categorized as embryonic or adult-derived stem cells. The embryonic stem (ES) cells are undifferentiated primitive cells derived from the preimplantation embryo with capability of dividing without differentiating or developing changes in karyotypes for a prolonged period of time. These ES cells may differentiate into specialized tissue in-vivo and in-vitro 21. ES cells are known to develop into cells and tissues of the three primary germ layers that ultimately lead to formation of an organism. As the development proceeds, the ES cells disappear by differentiating into specialized tissue, however a small number of stem cells are retained in the specialized tissues which are known as adult stem cells or somatic stem cells 22. The adult stem cells, in contrast to ES cells possess a limited capacity for self-renewal and differentiation, a process usually limited to the organ of origin. Among adult stem cells, the best-defined cells are the hematopoietic stem cells (HSC), mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) and intestinal stem cells (ISC). HSCs are stem cells isolated from the blood and bone marrow and possess the ability to give rise to red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets 23. HSCs are under study in the treatment of IBD 24, 25. The preliminary results of the ASTIC trial (Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation International Crohn’s Disease) suggests that immunoablation and hematopoetic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) may be effective in treating CD; but high rates of serious adverse events may make it unsuitable for the vast majority of patients 26. The ISCs are located at the base of crypt of Lieberkühn and are positive for Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5 (LGR5+) 27. The ISCs play key role in regeneration of intestinal epithelium and are focus of intense investigations 27.

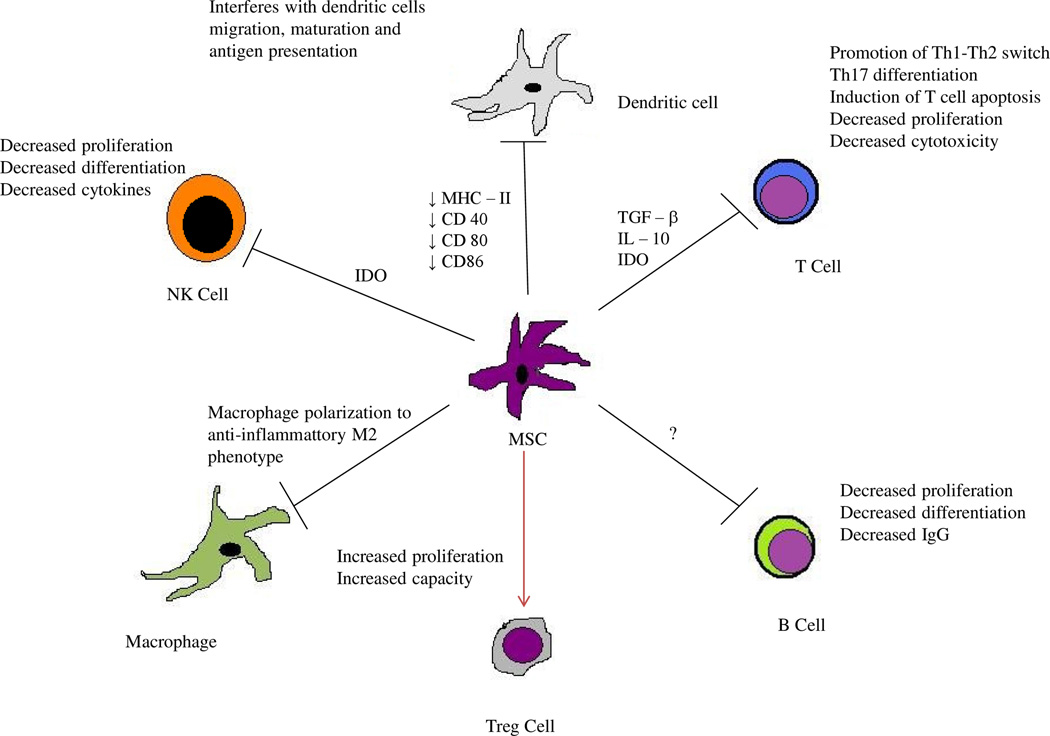

MSCs are non-hematopoietic multi-potent stem cells that have the capacity to differentiate into a limited array of differentiated cell types of mesodermal lineage including chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and adipocytes under different micro-environmental conditions, culture media and supplements 28. MSCs have been isolated from various tissues including the bone marrow, adipose tissue and human umbilical cord 29. Their properties include in-vitro proliferation with plastic-adherent properties bearing fibroblast-like morphology, the expression of mesenchymal stem cell markers and stem cell specific genes, the ability to form colonies and differentiate into various cell lineages 30–33. Recently, MSCs have been demonstrated to have immunoregulatory properties by suppression of allogeneic lymphocyte proliferation when added to mixed lymphocyte reaction and in mouse models of inflammation 34, 35. The immunomodulation by MSCs is thought to be a multi stage process 36. MSCs have been shown to migrate to sites of inflammation in response to stromal cell derived factor (SDF) −1 alpha 37 or secondary lymphoid tissue chemokines in-vivo 38 and complement proteins, growth factors, and chemokines in-vitro 39, 40. At the site of inflammation, the MSCs have been shown to require activation by interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) or interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) in order to exert immunosuppressive effect 41, 42. The activated MSCs produce immunosuppressive soluble factors including indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase (IDO), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), TNF - alpha stimulated protein/ gene 6 (TSG-6), and nitric oxide (NO) leading to macrophage polarization to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, induction of tolerogenic dendritic cells (DCs) and T regulatory cells in-vivo, promotion of Th1–Th2 switch, inhibition of mast cell and Th17 differentiation as well as induction of T-cell apoptosis 41, 43–45. MSCs have also been shown to interfere with dendritic cell (DC) function (migration, maturation and antigen presentation) by variety of mechanisms including down regulation of DC maturation markers like major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, CD40, CD80 and CD86 46–50. MSCs also exert their immunomodulation by a number of contact dependent mechanisms involving FAS/FAS ligand, programmed death-1/programmed death ligand-1, galectins, CD39-induced adenosine and Notch signaling 49–53(Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Different mechanisms of immunoregulation by mesenchymal stem cells

Given the in-vivo and in-vitro immunoregulatory potential of MSC, multiple studies have been conducted to assess safety and efficacy of stem cell (MSC) therapy in IBD. Two forms of MSC therapy have been utilized, one involves systemic infusion of stem cells for CD and UC, and the other involves localized application of stem cells for perianal CD. In this study we perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy of stem cell therapy without the use of any conditioning, myeloablation or total body radiation for treatment of IBD.

METHODS

We followed the standard Cochrane guidelines and the PRISMA statement for performing and reporting systematic review 54, 55.

Search strategy

A systematic review of English and non- English articles was performed using PubMed (since inception to March 2015) and EMBASE (since inception to November 2014). The search was performed independently by the authors (MD, KM and JL), and by an information library specialist (Larry Prokop). We also identified additional studies by searching bibliographies and abstracts presented at the Digestive Disease Week, American College of Gastroenterology and United European Gastroenterology Week from 2005 to 2014. We used free text words and MeSH terms with and without Boolean operators (“AND”, “OR”) to increase the sensitivity of the search 56. The detailed search strategy is available in supplementary table 1.

Study selection

Studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (i) Human studies (ii) Included patients with IBD (iii) MSCs were used for treatment of IBD (iii) No preparatory regimen for immunosuppression that is whole body irradiation or myeloablation (iv) Efficacy and adverse events were reported (v) The study was published as peer reviewed paper, letter or abstract. Exclusion criteria were i) Non human studies ii) Use of total body irradiation or myeloablative regimen.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (K.M & M.D) extracted data from the selected studies using standardized data extraction forms. These forms included: a) Author b) Journal c) Year of publication d) Country where study was performed e) Type of study f) Sample size g) Number of CD cases and UC cases h) Number of healthy controls (if any) i) Type and source of stem cells j) Primary outcome k) Efficacy outcome and m) Adverse events.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcomes of this analysis were proportion of patients with healed fistula after local injection of MSCs as defined by the study investigators and proportion of patients with induction of remission after systemic infusion of MSCs. Freeman-Tukey transformation 57 was used to calculate pooled proportions under the fixed and random effects model 58. The heterogeneity (i.e, between-study variation) of the results between the studies was assessed graphically by using chi square test of homogeneity and the inconsistency index (I2) 59. Inconsistency indexes describe the percentage of total variation across studies that are due to heterogeneity rather than to chance. An inconsistency index of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, <40% as low heterogeneity and values greater than 50% may be considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity 60. Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding one study at a time to reflect influence of individual study on pooled proportion. Statistical analysis was performed in R statistical software 61 using “meta” package for meta-analysis 62.

Assessment of study quality and bias

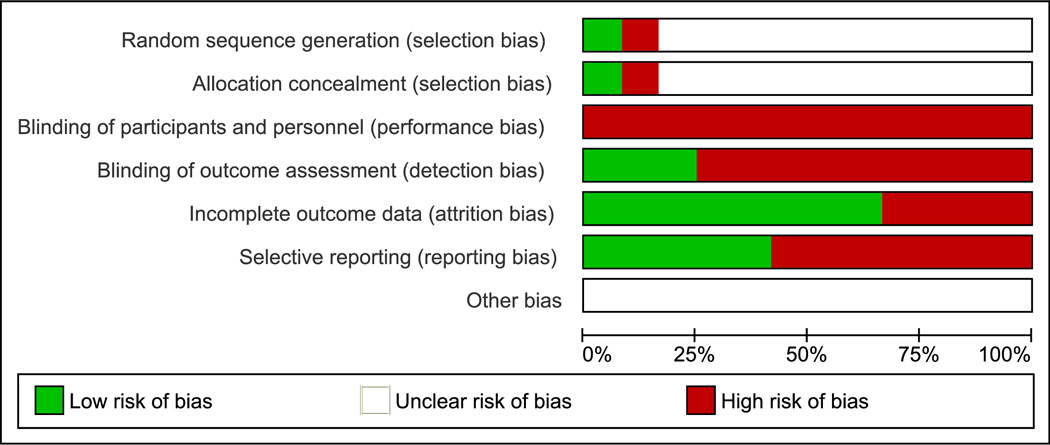

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed by two investigators (M.D. and K.M.), independently using Cochrane risk of bias tool 55. The studies were scored across five categories: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias.

Results

Search results

The initial search strategy yielded 4828 abstracts for review, of which 36 were selected for detailed review and 12 met the inclusion criteria (Supplementary figure 1). Twenty-three studies were excluded for being non-human studies or using myeloablative preparatory regimen or radiation. A study by Herreross et al. 63 was excluded; as it was a randomized, single blind trial of ASCs vs. fibrin glue vs. ASCs plus fibrin glue in 200 patients with cryptoglandular perianal fistulas and did not include IBD patients. We first report the efficacy and safety of stem cells for perianal CD which involved local application of stem cells and then report the efficacy and safety of stem cells for luminal IBD separately as that involved systemic infusion of stem cells.

Efficacy of SCT for Peri-anal CD (Local therapy)

Garcia-Olmo et al., in 2003, were the first investigators to report a case of successful healing of perianal fistula in a CD patient (who previously failed multiple immunosuppressive therapies) by local injection of autologous adipose derived stem cells (ASCs) 64. The same group later conducted a phase I trial of local injections of autologous ASCs in five CD patients who had rectovaginal, perianal and/or enterocutaneous fistulas. The study demonstrated complete closure in three out of four rectovaginal or perianal fistula (75%) and three out of four enterocutaneous fistulas (75%) at eight weeks post treatment 65.

Fibrin glue alone has often been tried to close peri-anal fistulas, however, previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews had showed no significant difference between outcomes of fibrin glue vs. conventional surgery 66, 67. The study by Garcia-Olmo et al. showed that a combination of autologous ASCs and fibrin glue produced better results than fibrin glue alone 68. This randomized, open label trial studied seven patients with CD who received fibrin glue alone compared to 7 CD patients who received fibrin glue plus 2 million ASCs. If the fistula had not healed at 8 weeks, the patients received a second dose of fibrin glue or fibrin glue plus 4 million ASCs in respective arms. Five out of seven patients (71%) in stem cells plus fibrin glue group had healed fistulas (defined as closure of external opening and absence of suppuration upon pressure) compared to one out of seven patients (14%) in fibrin glue alone group at 8 weeks after last treatment. While the study showed effectiveness of ASC plus fibrin glue over fibrin glue alone (relative risk = 5), the results were not statistically significant for CD patients (p=0.1). Ciccocioppo R. et al performed a study to determine fistula closure by local injection of bone marrow derived autologous MSCs in 10 patients with CD 69. One patient had multiple enterocutaneous fistulas and others had complex perianal fistula. The patients were treated with serial local injection of MSCs every 4 weeks over a 16-week period, on an average of 4 doses (range 2–5). Six out of 9 patients with complex perianal fistula (67%) and one patient with multiple enterocutaneous fistulas had complete closure evident on clinical exam as well as MRI. A study by de la Portilla et al. used expanded allogeneic ASCs (eASCs) and demonstrated the effectiveness of local injections of eASCs in CD patients with peri-anal fistulas 70. Twenty-four patients received 20 million eASCs in draining fistula tract by local injection. If fistula closure was incomplete at week 12, a second dose of 40 million eASCs was given. The fistula closure was strictly defined as: absence of suppuration through the external orifice and complete re-epithelization, plus absence of collections measured by MRI. Five out of 18 fistulas closed (28%) on per-protocol analysis; and 7 out of 18 patients (47%) had closure of external openings at 24 weeks post treatment. A phase I clinical study conducted by Cho et al used autologous ASCs for treatment of fistulizing CD and defined fistula healing as complete closure of the fistula track, and internal and external openings without drainage or signs of inflammation 71. Three out of 10 patients had complete healing of fistula at 8 weeks post treatment. This was followed by phase II study from the same group, which is the largest MSC study for perianal CD to date and confirmed the effectiveness of autologous ASCs in fistulizing CD 72. Twenty seven out of 33 patients (82%) had complete fistula healing at 8 weeks post treatment defined as complete closure of the fistula track, and internal and external openings without drainage or signs of inflammation. The authors recently published a follow up study in which the patients were followed for 2 years regardless of response in the initial trial73. The study showed that at 24 months, by modified per-protocol analysis 21 out of 26 patients (80.8%) had sustained closure of the fistula.

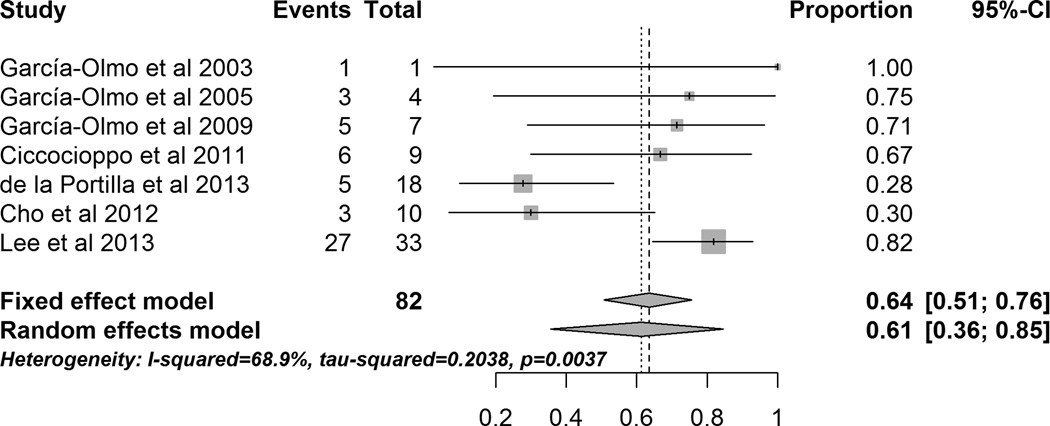

A meta-analysis of all perianal CD studies showed that 61.3% (95% CI 35.6% – 84.6%) of patients had healed fistula after local MSC administration (Figure 3). However, the included studies had high heterogeneity (I2 = 68.9%). Sensitivity analysis performed by excluding studies sequentially showed that by excluding the de la Portilla et al. 70 study the heterogeneity decreased to moderate level (I2 = 44.3%) and by excluding the Lee et al.72 study the heterogeneity decreased to moderate level (I2 = 41.5%) . While, de la Portilla et al. used MRI to define fistula closure, they also reported number of patients who had closure of external opening of fistula. When we used number of patients with closed external opening (7 of 18) for the meta-analysis, the heterogeneity (I2) reduced to 58.5%. MRI is considered as standard method of fistula healing in clinical trials by ECCO 74 as it shows residual inflammation in the fistula track despite the external closure of the fistula; only two out of seven studies have used MRI to evaluate healing of the fistula. Table 1 gives more details of the studies and efficacy outcomes.

Figure 3.

Forrest plot of studies evaluating healing of peri-anal fistulas (peri-anal CD) after local administration/injection of MSCs.

Table 1.

Stem cell therapy by local injection for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease

| Name of Study | Type of Study | Location | CD | Intervention | Type and source of Stem Cells |

Outcome | Results | Use of MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| García-Olmo et al 2003 | Case report | Spain | 1 | Local injection of stem cells |

Autologous, Adipose tissue |

Reepithelialization of external opening of fistula |

Fistula healed in 1 week, No recurrence till 3 months post treatment |

No |

| García-Olmo et al 2005 | Phase I, open label, single arm |

Spain | 5 | Local injection of stem cells |

Autologous, Adipose tissue |

Reepithelialization of external opening of fistula |

3 out of 4 rectovaginal or perianal fistula (75%) and 3 out of 4 enterocutaneous fistulas (75%) healed at eight weeks post treatment. |

No |

| García-Olmo et al 2009 | Phase II, open label, double arm, randomized |

Spain | 14 | Local injection of stem cells plus fibrin glue as compared to fibrin glue alone |

Autologous, Adipose tissue |

Reepithelialization of external opening of fistula |

5 out 7 fistulas (71%) healed in stem cells plus fibrin glue group as compared to 1 out of 7 fistulas (14%) healed in fibrin glue alone group after 8 weeks of treatment |

No |

| Ciccocioppo et al 2011 | Open label, single arm |

Italy | 10 | Local injection of stem cells |

Autologous, Bone marrow |

Complete closure evident on clinical exam as well as MRI |

One patient with multiple enterocutaneous and 6 out of 9 patients (67%) with complex perianal fistula had complete closure and other 3 had incomplete closure at 8 weeks post treatment |

Yes |

| de la Portilla et al 2013 | Phase I/IIa open label, single arm |

Spain | 24 | Local injection of stem cells |

Allogeneic, Adipose tissue |

Fistula closure was defined as: absence of suppuration through the external orifice and complete re- epithelization, plus absence of collections measured by MRI |

5 out of 18 fistulas (28%) closed at 24 weeks post treatment. 7 out of 18 patients (47%) had closure of external openings at 24 weeks post treatment. |

Yes |

| Cho et al 2012 | Phase I, open label, single arm |

Korea | 10 | Local injection of stem cells |

Autologous, Adipose tissue |

Healing of fistula | 3 out of 10 patients (30%) had complete healing of fistula at 8 weeks post treatment. |

No |

| Lee et al 2013 | Phase II, open label, single arm |

Korea | 43 | Local injection of stem cells |

Autologous, Adipose tissue |

Healing of fistula | 27 out of 33 patients (82%) had complete fistula healing at 8 weeks post treatment |

No |

CD: Crohn’s Disease

Safety of SCT for Peri-anal CD (Local therapy)

The case report, phase I and Phase II studies by Garcia-Olmo et al reported no serious adverse events (AEs) related to autologous ASCs administration 64, 65, 68. The duration of follow up was 3 months, 22 months and 12 months respectively. Ciccocioppo R. et al again reported no AEs in 12 months of follow up after administration of bone marrow derived autologous MSCs 69. However, the study by Portilla et al. which followed the patients for median 211 days (IQR 186–267 days) reported two serious AEs (fever and peri-anal abscess) after administration of allogeneic ASCs which lead to withdrawal of two patients (8%) from the study 70. The phase I study of autologous ASCs by Cho et al. which followed the patients for 8 months also reported three serious AEs (enterocolitis, seton application and infliximab administration for new fistulas unrelated to target fistula) in two patients (20%) requiring hospitalization 71. Notably, the Phase II study of autologous ASCs by Lee et al. reported no serious AEs in 12 months of follow-up period 72. Thus, two out of seven studies reported serious AEs after MSC administration, and both SAE were potentially related to underlying CD than treatment with MSC.

Minor adverse reaction reported in phase II study of autologous ASCs by Garcia-Olmo et al. included peri-anal sepsis (12 percent) in 12 months of follow-up period 68. The phase I study of autologous ASCs by Cho et al. which followed the patients for 8 months reported two non-serious AEs (pain at the site of injection and diarrhea) in five patients (50%) 71. The phase II study of autologous ASCs by Lee et al. followed the thirty-three CD patients for 12 months and reported postoperative pain, anal pain, and anal bleeding in 60%, 19%, and 7% of patients respectively after administration of autologous ASCs, none of which led to hospitalization. One patient was hospitalized for vitamin B12 deficiency. Two patients were hospitalized for exacerbation of CD and peritonitis respectively, which were deemed not related to ASC administration 72. Overall, the studies have demonstrated that administration of MSCs can lead to minor adverse reaction like perianal sepsis; but serious adverse reactions leading to hospitalization are less common and perhaps related to underlying CD activity.

Efficacy of SCT as systemic infusion for IBD

Onken et al. administered allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs by systemic infusion in 10 patients with active luminal CD refractory to steroids and immunomodulators (CRP >= 5 mg/L, CDAI >= 220) without performing any donor-recipient matching 75. Five patients were randomly assigned to receive high dose MSCs (8 million cells/kg), and 5 received low dose MSCs (2 million cells/kg). The study demonstrated significant decline in Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) by greater than 100 points in 3 patients at 14 days post treatment. One patient also achieved clinical remission (CDAI < 150) by day 7. The mean IBDQ score also increased significantly by Day 28 (113 vs. 146, p=0.008). Duijvestein et al. administered autologous bone-marrow derived MSCs in 2 doses of 1–2 million cells/kg, one week apart, in 10 patients with luminal CD refractory to steroids and immunomodulators. The study demonstrated a drop in CDAI by >= 70 from baseline in 3 patients at 6 weeks post treatment 76. However, none achieved remission. Lazebnik et al. also used allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs and cultured cells for 5–6 weeks to get donor MSC in a quantity of (1.5–2) × 108. The study demonstrated statistically significant decline in CDAI, Rahmilevich Clinical Activity Index (RCAI), Mayo and Gebs scales following intravenous administration of MSCs in 31 out of 39 patients with UC and 9 out of 11 patients with CD after 4 to 8 months of follow up 77. While all 50 patients were on steroids before the administration of MSCs, 34 of them were able to taper off steroids after MSCs administration. Liang et al. administered allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs (3 cases) and umbilical cord derived MSCs (4 cases), in 4 patients with CD and 3 patients with UC. The patients continued steroids and/or immunomodulators after the MSC infusion. At the 3-month visit, five patients achieved remission and maintenance of remission lasted for more than 24 months in two patients 78. However, the methods of culture of MSCs and definitions of remission were unclear. Forbes et al. also used allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs and gave weekly infusions of 2 million cells/kg body weight for 4 weeks to patient with active luminal CD refractory to immunomodulators. The study demonstrated significant decline in CDAI by > 100 in 12 out of 15 patients (80%, 95% confidence interval, 72%–88%), and induction of remission (defined as CDAI < 150) in 8 patients (53%, 95% confidence interval, 43%–64%), at 42 days after intravenous administration of MSCs 79.

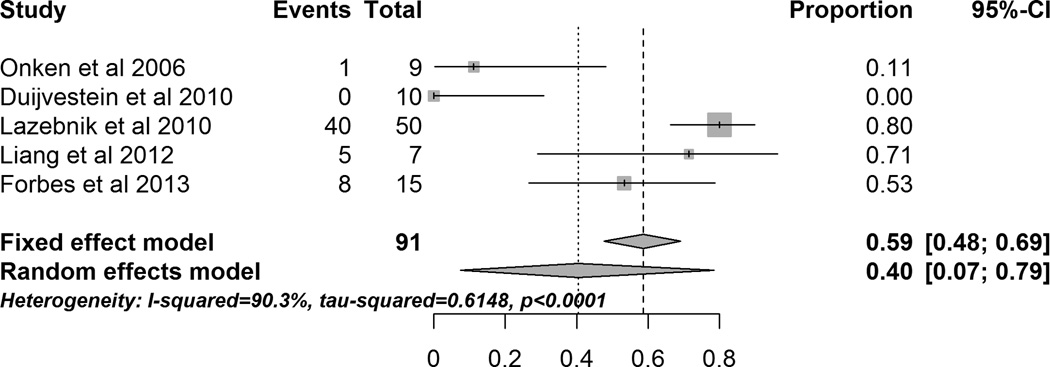

A meta-analysis of all studies of SCT as systemic infusion showed that 40.5% (95% CI 7.5% – 78.5%) of patients achieved remission after infusion of MSCs (Figure 4). The studies included had high heterogeneity (I2 = 90.3%) and a sensitivity analysis performed by excluding studies sequentially did not decrease the heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis by disease i.e CD or UC also did not decrease the high heterogeneity.

Figure 4.

Forrest plot of studies evaluating induction of clinical remission after systemic administration of MSCs.

Safety of SCT as systemic infusion for IBD

The study of allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs by Onken et al. followed ten CD patients for 28 days and reported one unrelated serious AE (anemia, 10%). There were no infusion reactions related to MSCs administration 75. Another study of allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs by Forbes et al. followed fifteen CD patients for 6 weeks and reported one serious AE (adenocarcinoma arising in a dysplasia associated lesion or mass) in one patient (6%). By retrospective charts reviews, the authors suspected that the cancer was present even before the MSC administration and the patient should not have been allowed to enter the study. However, the authors concluded that possibility of MSC contributing to progression of dysplasia to cancer could not be entirely excluded79. The study of autologous bone-marrow derived MSCs by Duijvestein et al. also reported no serious AEs in 6 months of follow up period 76. The study of allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs and umbilical cord derived MSCs by Liang et al. reported no serious AEs in 19 months of mean follow-up period 78. Thus, serious AEs related to MSC are relatively uncommon.

The study of allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs by Onken et al. which followed ten CD patients for 28 days reported five patients (50%) with non-serious AEs after systemic infusion of MSCs. The exact details of minor adverse reactions were not available. The study of autologous bone-marrow derived MSCs by Duijvestein et al. followed ten CD patients for 6 months and reported minor allergic reaction (10%), headache (30%), and taste and smell disturbances (90%) which were considered related to MSCs infusion. They also reported worsening of CD requiring hospitalization (20%), abdominal pain (30%), nausea (20%), fatigue (20%), anorexia (20%), dizziness (10%), vomiting (10%), bloating (10%), fever (10%), diarrhea (10%), common cold (10%), otitis media (10%); all of which were considered unrelated to MSCs infusion 76. In the study of allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs by Lazebnik et al., 12 patients (24%) had mild transfusion reaction following the administration of MSCs which included fever, arthralgia, and myalgia 77. Two patients (4%) developed hives and angioedema that were managed by using antihistamines and corticosteroids. The study of allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs and umbilical cord derived MSCs by Liang et al. followed seven patients for mean of 19 months (range 6–32) and reported three non-serious AEs (feeling of hot in face, insomnia, and increase in frequency of diarrhea associated with low grade fever) which did not require hospitalization 78. The study of allogeneic bone marrow derived MSCs by Forbes et al. followed fifteen CD patients for 6 weeks and reported dysgeusia (100%), headache (19%), lymphopenia (19%), increased alanine aminotransferase (19%), self-limiting infection (13%), and nausea (1%) which did not require hospitalization 79. Thus, commonly reported non-serious AEs after systemic infusion of MSCs were headache, diarrhea, mild transfusion reaction and taste and smell disturbances. All of the non-serious AEs were self limited.

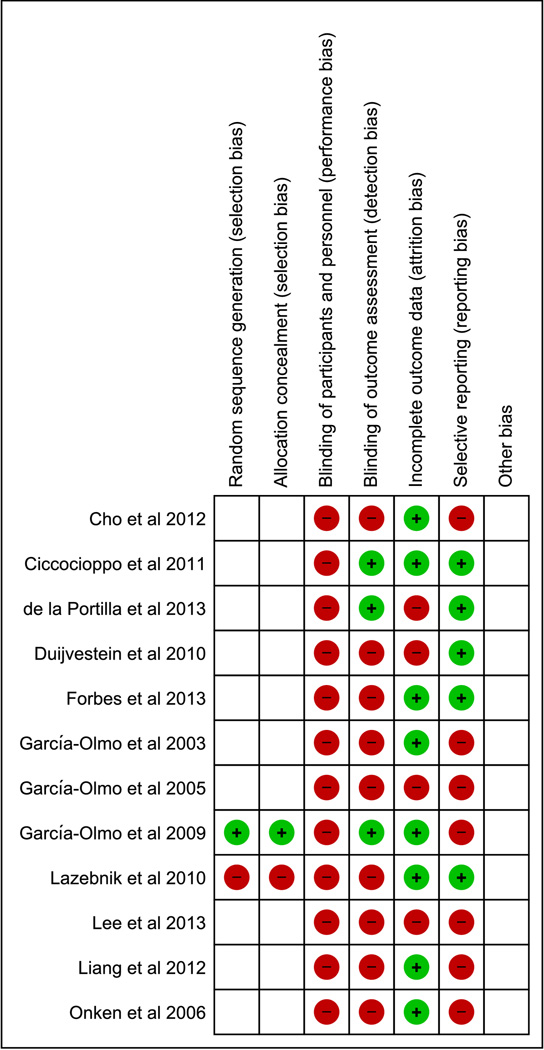

Assessment of Study Quality

There was overall high risk of performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and reporting bias in the studies included in the review (Figure 2A and 2B).

Figure 2.

A: Overall quality of the included studies assessed by Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool.

B: Risk of bias within studies assessed by Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool.

Plus sign denotes low risk. Minus sign denotes high risk. Blank denotes unclear risk.

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that SCT has good therapeutic potential with low risk of adverse events for IBD patients, particularly for those who have perianal disease and are treated with local therapy. The major advantage of mesenchymal SCT is that it does not require preparatory regimens involving high dose chemotherapy and/or radiation like bone marrow/hematopoietic stem cell transplant. As a result, it is associated with less adverse events and procedure related mortality. MSCs have regenerative and immunomodulatory properties which lead to reduction of inflammation and healing of affected intestinal tissue. Due to immunomodulatory properties of MSCs, healthy donors (instead of IBD patients) can also be used as a source of MSCs without increasing risk of rejection by the host.

Several limitations temper the findings of our analysis. First, out of 12 studies included in this review, only one study was randomized double arm trial comparing fibrin glue alone vs fibrin glue plus SCT. Second, studies used different sources of stem cells including adipose tissue, bone marrow and umbilical cord from same patient (autologous) as well as healthy volunteers (allogeneic). Third the efficacy of local injection of SCT in closure of fistula varied widely between 28% to 82%, among the studies. Fourth, the method of assessment of fistula closure and follow up period varied among the studies. Only two studies used MRI for assessment of fistula closure and the rest relied on clinical exam. Last, adverse events reporting was not standardized. Four out of 7 studies reported minor local reactions like perianal sepsis but serious adverse events requiring hospitalization were rare. There was one reported case of malignancy, an established complication of IBD. The commonly observed minor adverse events were dysgeusia, headache and diarrhea; but serious adverse events requiring hospitalization were rare. However, the definitions of adverse events used among studies varied significantly. Moreover, the SCT related and SCT unrelated AEs were not defined precisely.

A recent phase III study utilizing MSC’s to treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) failed to meet its primary end point 80. In the failure analysis of the GVHD study, Galipeau argued that immunoregulatory properties of MSCs vary between different donors (donor variance). The excessive expansion and replication of MSCs could also lead to lesser efficacy. Some recipients might have pre-existing alloimmunization leading to rejection of administered MSCs. Moreover, practice of cryopreservation till the day of procedure and thawing of MSCs several hours prior to administration could also lead to reduced efficacy 81. All these arguments can also be applied to MSC therapy for IBD. In addition, several novel immunomodulatory properties of MSCs have been recently identified which have not yet been implemented in clinical studies. Pretreatment of MSCs with IFN-γ has been shown to enhance therapeutic effects of MSCs in mouse model of colitis 82. Similarly, pre-exposure of umbilical cord blood MSCs with muramyl dipeptide (MDP) has been shown to increase ability of MSCs to suppress mononuclear cell proliferation, and in turn reduce the inflammation 83. MSCs with budesonide loaded Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) microparticles have been shown to exhibit enhanced IDO activity leading to increased suppression of peripheral blood mononuclear cells 84. Furthermore, adult stem cells other than MSC have recently been shown to exert an immunosuppressive effect 85. Thus these advances in preclinical studies need to be evaluated in treatment of IBD patients to increase the efficacy of MSC therapy.

Clinical trials that are currently underway (Supplementary table 2) to ascertain the safety and therapeutic benefits of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in IBD patients appear promising. However, they need to use standardized definitions of the side effects resulting directly from MSC therapy and incorporate more objective definitions of IBD remission like endoscopy, C reactive protein, fecal calprotectin and imaging including MRI for perianal CD.

Conclusion

MSCs are emerging as an alternative treatment for refractory IBD. Although, MSCs appear safe and potentially effective in initial studies, more studies in preclinical animal models and human studies that incorporate randomized controlled design are needed. Recent basic science advances in biology of MSCs needs to be incorporated in clinical trials to improve the efficacy of MSCs.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Stem cell therapy by systemic infusion for inflammatory bowel disease

| Name of Study |

Type of Study | Location | UC | CD | Intervention | Type and source of Stem Cells |

Outcome | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onken et al 2006 | Phase II, open label, double arm, randomized |

USA | 0 | 10 | Systemic infusion of low vs. high dose stem cells |

Allogeneic, Bone marrow |

CDAI |

|

| Duijvestein et al 2010 | Phase I, open label, single arm |

Netherlands | 0 | 10 | Systemic infusion of stem cells |

Autologous, Bone marrow |

CDAI and CDEIS |

|

| Lazebnik et al 2010 | Open label, double arm |

Russia | 69 | 21 | Systemic infusion of stem cells (39 UC and 11 CD patients) vs. Traditional treatment (30 UC and 10 CD patients) |

Allogeneic, Bone marrow |

CDAI, RCAI, Mayo and Gebs scales |

|

| Liang et al 2012 | n/a | China | 3 | 4 | Systemic infusion of stem cells |

Allogeneic, Bone marrow and Umbilical Cord |

CDAI, CAI |

|

| Forbes et al 2013 |

Phase II, open label, single arm. |

Australia | 0 | 16 | Systemic infusion of stem cells |

Allogeneic, Bone marrow |

CDAI, CDEIS |

|

UC: Ulcerative Colitis, CD: Crohn’s Disease, CDAI: Crohn’s Disease Activity Index, CDEIS: Crohn’s Disease Endoscopic Index of Severity, RCAI: Rachmilewich clinical activity index

Table 3.

Adverse events of stem cell therapy by local injection for fistulizing Crohn’s disease

| Adverse Event | Crohn’s Disease Patients with SCT Therapy (N = 104) |

Non IBD patients with SCT Therapy (N = 17) |

Crohn’s Disease Patients without SCT Therapy (N = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perianal infection | 8 | 3 | ? |

| Perianal abscess | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Intraabdominal abscess | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Proctalgia | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Cholecystitis | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fever | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Anxiety | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarhhea | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Uterine leiomyoma | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Allergic reaction | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Flare of Crohn’s disease | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Malignancy | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 4.

Adverse events of stem cell therapy by systemic infusion for inflammatory bowel disease

| Adverse Event | Number of patients affected (N = 93) |

|---|---|

| Taste or smell disturbances |

25 |

| Fever | 13 |

| Myalgia | 12 |

| Arthralgia | 12 |

| Headache | 6 |

| Increased ALT | 4 |

| Allergic reaction | 3 |

| Abdominal pain | 3 |

| Anorexia | 2 |

| Fatigue | 2 |

| Flare of Crohn’s disease | 2 |

| Lymphopenia | 2 |

| Nausea | 2 |

| Anemia | 1 |

| Common cold | 1 |

| Diarrhea | 1 |

| Dizziness | 1 |

| Insomnia | 1 |

| Neoplasia | 1 |

| Otitis media | 1 |

| Vaginal candidiasis | 1 |

| Viral gastroenteritis | 1 |

| Vomiting | 1 |

| Anxiety | 0 |

| Death | 0 |

| Perianal abscess | 0 |

| Perianal infection | 0 |

| Proctalgia | 0 |

| Uterine leiomyoma | 0 |

Acknowledgement

Grant Support: WAF’s laboratory is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI089714. The funding agencies had no role in the study analysis or writing of the manuscript. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors.

We thank Natalia Aladyshkina (Case Western Reserve University) for translating the text in some studies to English.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Writing assistance: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Study concepts/study design: MD and WAF, literature research, M.D., KM., JL, AB; data acquisition or data analysis/interpretation, MD, KM, JL; statistical analysis, MD and KM; manuscript drafting: MD and KM: manuscript revision for important intellectual content, MD, WAF, KM, AD and JL; manuscript final version approval, all authors.

References

- 1.Dave M, Papadakis KA, Faubion WA., Jr Immunology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Molecular Targets for Biologics. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:405–424. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poggioli G, Pierangeli F, Laureti S, et al. Review article: indication and type of surgery in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(Suppl 4):59–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.16.s4.9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicholls RJ. Review article: ulcerative colitis--surgical indications and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(Suppl 4):25–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.16.s4.5.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Dullemen HM, van Deventer SJ, Hommes DW, et al. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody (cA2) Gastroenterology. 1995;109:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jilani NZ, Akobeng AK. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn's disease: the CHARM trial. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P et al. Gastroenterology 2007;132:52–65. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:226–227. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318156e139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Stoinov S, et al. Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:228–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Donoghue DP, Dawson AM, Powell-Tuck J, et al. Double-blind withdrawal trial of azathioprine as maintenance treatment for Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 1978;2:955–957. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92524-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Present DH, Korelitz BI, Wisch N, et al. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with 6-mercaptopurine. A long-term, randomized, double-blind study. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:981–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198005013021801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, et al. Oral budesonide for active Crohn’s. disease Canadian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:836–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Marano C, et al. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:85–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.048. quiz e14–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:392–400. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dave M, Purohit T, Razonable R, et al. Opportunistic infections due to inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:196–212. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e3182a827d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh S, Kumar N, Loftus EV, Jr, et al. Neurologic complications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: increasing relevance in the era of biologics. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:864–872. doi: 10.1002/ibd.23011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dulai PS, Siegel CA. The Risk of Malignancy Associated with the Use of Biological Agents in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:525–541. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong L, Lako M, Buckley N, et al. Editorial: Our top 10 developments in stem cell biology over the last 30 years. Stem Cells. 2012;30:2–9. doi: 10.1002/stem.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muller FJ, Laurent LC, Kostka D, et al. Regulatory networks define phenotypic classes of human stem cell lines. Nature. 2008;455:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature07213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller G. Embryonic stem cell differentiation: emergence of a new era in biology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1129–1155. doi: 10.1101/gad.1303605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korbling M, Estrov Z. Adult stem cells for tissue repair - a new therapeutic concept? N Engl J Med. 2003;349:570–582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson A, Trumpp A. Bone-marrow haematopoietic-stem-cell niches. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:93–106. doi: 10.1038/nri1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Bosch O, Ricart E, Panes J. Review article: stem cell therapies for inflammatory bowel disease - efficacy and safety. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:939–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkey CJ. Stem cells as treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis. 2012;30(Suppl 3):134–139. doi: 10.1159/000342740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koo BK, Clevers H. Stem cells marked by the R-spondin receptor LGR5. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:289–302. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caplan AI. Adult mesenchymal stem cells for tissue engineering versus regenerative medicine. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:341–347. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, et al. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1294–1301. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells, The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez-Rey E, Anderson P, Gonzalez MA, et al. Human adult stem cells derived from adipose tissue protect against experimental colitis and sepsis. Gut. 2009;58:929–939. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.168534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:42–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood. 2002;99:3838–3843. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.English K. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stromal cell immunomodulation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91:19–26. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu H, Liu S, Li Y, et al. The role of SDF-1-CXCR4/CXCR7 axis in the therapeutic effects of hypoxia-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells for renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasaki M, Abe R, Fujita Y, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells are recruited into wounded skin and contribute to wound repair by transdifferentiation into multiple skin cell type. J Immunol. 2008;180:2581–2587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qiu Y, Marquez-Curtis LA, Janowska-Wieczorek A. Mesenchymal stromal cells derived from umbilical cord blood migrate in response to complement C1q. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:285–295. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.651532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponte AL, Marais E, Gallay N, et al. The in vitro migration capacity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: comparison of chemokine and growth factor chemotactic activities. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1737–1745. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, et al. Role for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:386–398. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ge W, Jiang J, Arp J, et al. Regulatory T-cell generation and kidney allograft tolerance induced by mesenchymal stem cells associated with indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression. Transplantation. 2010;90:1312–1320. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181fed001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brown JM, Nemeth K, Kushnir-Sukhov NM, et al. Bone marrow stromal cells inhibit mast cell function via a COX2-dependent mechanism. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:526–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson P, Souza-Moreira L, Morell M, et al. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells induce immunomodulatory macrophages which protect from experimental colitis and sepsis. Gut. 2013;62:1131–1141. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.English K, Barry FP, Mahon BP. Murine mesenchymal stem cells suppress dendritic cell migration, maturation and antigen presentation. Immunol Lett. 2008;115:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Djouad F, Charbonnier LM, Bouffi C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the differentiation of dendritic cells through an interleukin-6-dependent mechanism. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2025–2032. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nauta AJ, Kruisselbrink AB, Lurvink E, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit generation and function of both CD34+-derived and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:2080–2087. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang B, Liu R, Shi D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells induce mature dendritic cells into a novel Jagged-2-dependent regulatory dendritic cell population. Blood. 2009;113:46–57. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-154138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li YP, Paczesny S, Lauret E, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells license adult CD34+ hemopoietic progenitor cells to differentiate into regulatory dendritic cells through activation of the Notch pathway. J Immunol. 2008;180:1598–1608. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akiyama K, Chen C, Wang D, et al. Mesenchymal-stem-cell-induced immunoregulation involves FAS-ligand-/FAS-mediated T cell apoptosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:544–555. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by activation of the programmed death 1 pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1482–1490. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sioud M. New insights into mesenchymal stromal cell-mediated T-cell suppression through galectins. Scand J Immunol. 2011;73:79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higgins JPTGSE. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] Vol. 2014. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leeflang MM, Deeks JJ, Gatsonis C, et al. Systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:889–897. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-12-200812160-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freeman MTJW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1950;21:607–611. [Google Scholar]

- 58.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. GRADE guidelines: 7 Rating the quality of evidence--inconsistency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1294–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schwarzer G. meta: General Package for Meta-Analysis. R package version 4.1–0. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Herreros MD, Garcia-Arranz M, Guadalajara H, et al. Autologous expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex cryptoglandular perianal fistulas: a phase III randomized clinical trial (FATT 1: fistula Advanced Therapy Trial 1) and long-term evaluation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:762–772. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318255364a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garcia-Olmo D, Garcia-Arranz M, Garcia LG, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for treatment of rectovaginal fistula in perianal Crohn’s disease: a new cell-based therapy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:451–454. doi: 10.1007/s00384-003-0490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garcia-Olmo D, Garcia-Arranz M, Herreros D, et al. A phase I clinical trial of the treatment of Crohn’s fistula by adipose mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1416–1423. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cirocchi R, Farinella E, La Mura F, et al. Fibrin glue in the treatment of anal fistula: a systematic review. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2009;3:12. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-3-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cirocchi R, Santoro A, Trastulli S, et al. Meta-analysis of fibrin glue versus surgery for treatment of fistula-in-ano. Ann Ital Chir. 2010;81:349–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garcia-Olmo D, Herreros D, Pascual I, et al. Expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula: a phase II clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:79–86. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181973487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ciccocioppo R, Bernardo ME, Sgarella A, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in the treatment of fistulising Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2011;60:788–798. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.214841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de la Portilla F, Alba F, Garcia-Olmo D, et al. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived stem cells (eASCs) for the treatment of complex perianal fistula in Crohn’s disease: results from a multicenter phase I/IIa clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:313–323. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1581-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cho YB, Lee WY, Park KJ, et al. Autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells for the treatment of Crohn’s fistula: a phase I clinical study. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:279–285. doi: 10.3727/096368912X656045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee WY, Park KJ, Cho YB, et al. Autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells treatment demonstrated favorable and sustainable therapeutic effect for Crohn’s fistula. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2575–2581. doi: 10.1002/stem.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cho YB, Park KJ, Yoon SN, et al. Long-Term Results of Adipose-Derived Stem Cell Therapy for the Treatment of Crohn’s Fistula. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015 doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:63–101. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Onken JGD, Hanson J, Pandak M, Custer L. Sucessful outpatient treatment of refractory Cron’s disease using adult mesenchymal stem cells. American College of Gastroenterology Annual Meeting. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duijvestein M, Vos AC, Roelofs H, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell treatment for refractory luminal Crohn’s disease: results of a phase I study. Gut. 2010;59:1662–1669. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.215152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lazebnik LB, Konopliannikov AG, Kniazev OV, et al. [Use of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of intestinal inflammatory diseases] Ter Arkh. 2010;82:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liang J, Zhang H, Wang D, et al. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in seven patients with refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2012;61:468–469. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Forbes GM, Sturm MJ, Leong RW, et al. A phase 2 study of allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells for luminal Crohn’s disease refractory to biologic therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martin PJUJP, Soiffer RJ, Klingemann H, Waller EK, Daly AS, Herrmann RP, Kebriaei P. Prochymal improves response rates in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease (SR-GVHD) involving the liver and gut:Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial in GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:169–170. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Galipeau J. The mesenchymal stromal cells dilemma--does a negative phase III trial of random donor mesenchymal stromal cells in steroid-resistant graft-versus-host disease represent a death knell or a bump in the road? Cytotherapy. 2013;15:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Duijvestein M, Wildenberg ME, Welling MM, et al. Pretreatment with interferon-gamma enhances the therapeutic activity of mesenchymal stromal cells in animal models of colitis. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1549–1558. doi: 10.1002/stem.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim HS, Shin TH, Lee BC, et al. Human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells reduce colitis in mice by activating NOD2 signaling to COX2. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1392–1403. e1–e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ankrum JA, Dastidar RG, Ong JF, et al. Performance-enhanced mesenchymal stem cells via intracellular delivery of steroids. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4645. doi: 10.1038/srep04645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dave M, Hayashi Y, Gajdos GB, et al. Stem Cells for Murine Interstitial Cells of Cajal Suppress Cellular Immunity and Colitis Via Prostaglandin E Secretion. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(5):978–990. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.