Abstract

Cancer survivors face several challenges following the completion of active treatment, including uncertainty about late effects of treatment and confusion about coordination of follow-up care. The authors evaluated patient satisfaction with personalized survivorship care plans designed to clarify those issues. The authors enrolled 48 patients with breast cancer and 10 patients with colorectal cancer who had completed treatment in the previous two months from an urban academic medical center and a rural community hospital. Patient satisfaction with the care plan was assessed by telephone interview. Overall, about 80% of patients were very or completely satisfied with the care plan, and 90% or more agreed that it was useful, it was easy to understand, and the length was appropriate. Most patients reported that the care plan was very or critically important to understanding an array of survivorship issues. However, only about half felt that it helped them better understand the roles of primary care providers and oncologists in survivorship care. The results provide evidence that patients with cancer find high value in personalized survivorship care plans, but the plans do not eliminate confusion regarding the coordination of follow-up care. Future efforts to improve care plans should focus on better descriptions of how survivorship care will be coordinated.

About 12.5 million people in the United States were living with a personal history of cancer in 2009, including more than 2.5 million women with breast cancer and more than 1 million men and women with colorectal cancer (Howlader et al., 2012). An extensive body of research provides evidence that cancer survivors frequently experience late effects from their cancer and its treatment, including psychological distress, pain, impaired organ function, sexual dysfunction, cosmetic changes, and limitations in mobility, communication, and cognition (Ganz, 2000; Harrington, Hansen, Moskowitz, Todd, & Feuerstein, 2010; Hewitt, Greenfield, & Stovall, 2005; Stein, Syrjala, & Andrykowski, 2008; Strieker & Jacobs, 2008). A landmark report by the Institute of Medicine (Hewitt et al., 2005) recognized that the system of delivering care to the growing number of cancer survivors was inadequate. Specifically, it suggested that the transition of medical care following cancer treatment often is not well coordinated, and many cancer survivors and providers are unaware of late effects and heightened health risks related to the cancer and its treatment. A key recommendation of the report was that patients with cancer completing primary treatment should be provided with a survivorship care plan that includes a comprehensive treatment and care summary and follow-up plan.

Although the Commission on Cancer (2012) added the provision of a survivorship care plan to its cancer program standards, sparse evidence exists regarding the effectiveness and optimal content of care plans (Salz, Oeffinger, McCabe, Layne, & Bach, 2012). Two small studies of personalized survivorship care plans suggested reductions in unmet needs among cancer survivors and increased adherence with medical surveillance recommendations (Jefford et al., 2011; Oeffinger et al, 2011). However, a randomized trial in Canada (Grunfeld et al., 2011) found that early-stage breast cancer survivors who received a survivorship care plan experienced no benefit in cancer-related distress, quality of life, patient satisfaction, and other measures after one year compared to patients who received only a standard discharge visit. Although the findings are limited by a short follow-up time and may not be directly generalizable to the United States, they provide impetus for additional research on the optimal format and delivery of cancer survivorship care plans (Smith & Snyder, 2011).

The authors of the current article conducted a study of survivorship care plans for patients with breast or colorectal cancer in an urban academic medical center and a small rural community hospital in Vermont. The authors evaluated patients' satisfaction with the survivorship care plans and assessed the importance of various domains of the care plan for the patient. The results can be used to optimize the future design of care plans, which would maximize their usefulness to the patient.

Methods

Study Population

The current study was conducted at two sites: Fletcher Allen Health Care, an academic medical center in Burlington, VT, and the Norris Cotton Cancer Center-North, a rural extension of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center located at Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital in St. Johnsbury. Eligible patients had stages 0–III breast cancer or stages II–IV colorectal cancer, were aged 18 years and older, and had completed treatment with curative intent within the preceding 12 months. The study was approved by the human subjects institutional review boards at the University of Vermont and Dartmouth Medical School, and all patients provided written informed consent. From January to July 2011, a total of 89 patients were invited to participate in the study and 78 agreed (88%), including 61 with breast cancer and 17 with colorectal cancer.

Survivorship Care Plans

Survivorship care plans were prepared by advanced practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) in consultation with oncologists at each study site using the Survivorship Care Plan Builder software tool developed by Journey Forward™ (Hausman, Ganz, Sellers, & Rosenquist, 2011). Each survivorship care plan was developed using the Journey Forward templates for breast and colorectal cancer, and contained the following domains: a summary of the patient diagnosis, a summary of the patient's treatment, information on recommended follow-up tests and secondary cancer prevention, information received on late effects of cancer treatments, and a list of national and local health-promotion resources. The survivorship care plan was delivered to and discussed with patients by the advanced practice providers during a care plan visit at the clinic. The visit lasted about one hour (range = 45–90 minutes) and occurred about 1–6 months following completion of initial oncologic treatment for cancer. The survivorship care plans were modified if necessary with patient input and finalized. A copy of the final survivorship care plan also was mailed to the patients' primary care providers. Although the care plan was added to patient electronic medical records and the oncologists were aware of the study, the oncologists were not directly notified of the care plans for their patients.

Data Collection

Telephone interviews were conducted with the patients about two months after the care plan visit. As many as 15 attempts were made to contact participants, including calls at varying times on weekdays, weeknights, and weekends, as well as voicemails left with a toll-free number to return calls. Of the 78 patients who enrolled in the study, 58 (74%) completed a telephone interview. The remaining 20 either refused to complete the telephone interview (n=6) or could not be contacted (n = 14). Nonrespondents were more likely to be older than age 65 years, but had similar patterns of cancer stage and treatment to those who completed the interview. The telephone interview included questions to assess the care plan as a whole, as well as questions targeted specifically toward the various domains and elements of the care plan. A variety of question types were used, including categorical response, Likert scale, and open-ended response. Patients also were asked to provide basic demographic information including marital status, education, and family income. Medical data, including cancer stage, date of diagnosis, and treatment information, were obtained from the patients' medical records.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS®, version 9. Descriptive statistics were prepared for each survey question of interest. For certain questions pertaining to the care plan in general, the complete set of response frequencies was described. For other questions, response options were collapsed into two groups for analysis. Response options for accuracy (“Was it accurate?”) and ease of understanding (“Was it easy to understand?”) of the various domains included “yes,” “no,” and “somewhat.” The responses were categorized as agree (“yes”) or did not agree (“no” or “somewhat”). Response options for whether the care plan was important in helping to understand general domains of survivorship (e.g., possible late effects of treatment) were dichotomized as “very important” or “critically important” and “somewhat important” or “not important at all.” Response options for whether the care plan was important in helping to understand specific elements of the care plan (e.g., recommended frequency of follow-up tests) were dichotomized as agree (“yes”) and did not agree (“no” or “not sure”). Tests for interaction by cancer site and facility type were conducted using Fisher's exact tests. The 95% confidence intervals were constructed using the Clopper-Pearson method for exact confidence limits for a binomial proportion (Clopper & Pearson, 1934).

Results

A total of 58 patients completed the interview, including 48 with breast cancer and 10 with colorectal cancer. The median age of participants was 54 years (range = 35–75 years) among patients with breast cancer and 59 years (range = 41–70 years) among patients with colorectal cancer. All patients were non-Hispanic Whites, 74% were married or living as a couple, and more than 85% reported good, very good, or excellent health. Compared to patients with breast cancer, the patients with colorectal cancer were more likely to be aged 65 years and older, have less education, have more advanced cancers, and to have received chemotherapy (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population (N = 58)

| Breast (n = 48) |

Colorectal (n = 10) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | n |

| Facility | ||

| Urban academic medical center | 30 | 7 |

| Rural community hospital | 18 | 3 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 35–49 | 12 | 3 |

| 50–64 | 25 | 3 |

| 65–75 | 11 | 4 |

| Education | ||

| No college | 11 | 5 |

| Some college | 14 | 1 |

| College graduate | 23 | 4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married, civil union, or partner | 36 | 7 |

| Widowed, separated, or divorced | 9 | 2 |

| Never married | 3 | 1 |

| Annual family income ($)a | ||

| Less than 35,000 | 5 | 1 |

| 35,000–75,000 | 17 | 2 |

| More than 75,000 | 19 | 4 |

| Self-rated overall health | ||

| Poor | 3 | – |

| Fair | 3 | – |

| Good | 22 | 3 |

| Very good | 15 | 4 |

| Excellent | 5 | 3 |

| Cancer stage | ||

| 0 | 4 | – |

| I | 25 | – |

| II | 15 | 2 |

| III | 4 | 7 |

| IV | – | 1 |

| Treatments receivedb | ||

| Surgery | 48 | 10 |

| Radiation | 45 | 2 |

| Chemotherapy | 25 | 10 |

| Hormone therapy | 38 | – |

Data on income were missing for seven patients with breast cancer and three patients with colorectal cancer.

Most patients received more than one treatment.

In general, all patients were highly satisfied with the survivorship care plans (see Table 2). Among both cancer types, 46 patients (79%) were very or completely satisfied with the care plan, 53 (91%) agreed that the care plan was useful and easy to understand, and 54 (91%) said that the length was just right. Almost all patients found the in-person care plan visit useful and would recommend a care plan to others. However, seven patients with breast cancer (12%) and four patients with colorectal cancer (40%) reported that they would need help using the care plan. No statistically significant differences were noted in responses to these items between patients with breast or colorectal cancer (all p interaction ≥ 0.18).

TABLE 2.

Patient Satisfaction With the Survivorship Care Plan (N = 58)

| Breast (n = 48) |

Colorectal (n = 10) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | n |

| Overall satisfaction with care plan | ||

| Not at all satisfied | 1 | – |

| Indifferent | 2 | 1 |

| Somewhat satisfied | 7 | 1 |

| Very satisfied | 23 | 7 |

| Completely satisfied | 15 | 1 |

| Care plan was useful. | ||

| Strongly disagree | – | – |

| Disagree | 2 | – |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 3 | – |

| Agree | 11 | 3 |

| Strongly agree | 32 | 7 |

| Care plan was easy to understand. | ||

| Strongly disagree | – | – |

| Disagree | – | – |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 2 | – |

| Agree | 11 | 5 |

| Strongly agree | 35 | 5 |

| Length was just right.a | ||

| Strongly disagree | – | – |

| Disagree | – | – |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 3 | – |

| Agree | 8 | 4 |

| Strongly agree | 36 | 6 |

| Would need help using care plan. | ||

| Strongly disagree | 23 | 3 |

| Disagree | 14 | 3 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 4 | – |

| Agree | 7 | 3 |

| Strongly agree | – | 1 |

| Care plan visit was useful. | ||

| Not at all useful | 1 | – |

| Somewhat useful | 7 | – |

| Very useful | 40 | 10 |

| Would recommend a care plan to others. | ||

| No | 1 | – |

| Yes | 47 | 10 |

Data were missing for one patient with breast cancer regarding length of the survivorship care plan.

When examined according to facility type, similar results for all patients combined (breast and colorectal) were obtained for the urban academic medical center (n = 37) and the rural community hospital (n = 21), with the exception of ease of understanding the care plan (data not shown). At the urban academic medical center, 30 patients (81%) strongly agreed and seven patients (19%) agreed that the care plan was easy to understand, compared to 10 (48%) and 9 (43%) at the rural community hospital, respectively, where an additional two patients (10%) neither agreed nor disagreed (p interaction = 0.01).

Analyses of specific care plan domains revealed that each section was rated very highly for accuracy and ease of understanding, with the exception of which doctor will order tests for recurrences or new cancers (see Table 3). Only 28 patients with breast cancer (58%) and seven with colorectal cancer (70%) understood which doctor would order these tests. About 50%–70% of patients with breast cancer reported that the care plan was very or critically important to helping them understand the various domains covered by the care plan. High levels of importance (80%–100%) were reported among patients with colorectal cancer. All patients reported that the section on tests needed in the future was the most important section for improving their understanding. Analyses according to facility type revealed no statistically significant differences, although a higher proportion of patients at the rural community hospital (n = 14,74%) found the care plan very or critically important for understanding their diagnosis compared to patients at the academic medical center (n = 17,49%) (p interaction = 0.09; data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Patient Evaluation of Specific Survivorship Care Plan Domains (N = 58)

| Breast (n = 48) | Colorectal (n = 10) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | na | % | 95% Cl | na | % | 95% Cl |

| Information was accurate. | ||||||

| Diagnosis information | 43 | 90 | [77.3, 96.5] | 9 | 90 | [55.5, 99.8] |

| Treatment information | 41 | 85 | [72.2, 93.9] | 7 | 70 | [34.8, 0.93] |

| Easy to understand | ||||||

| Diagnosis information | 44 | 92 | [80, 97.7] | 10 | 100 | [69.2, 100] |

| Treatment information | 45 | 94 | [82.8, 98.7] | 9 | 90 | [55.5, 99.8] |

| Which doctor will order tests to detect recurrences or new cancers | 28 | 58 | [43.2, 72.4] | 7 | 70 | [34.8, 93.3] |

| Possible long-term and late effects | 40 | 83 | [69.8, 92.5] | 9 | 90 | [55.5, 99.8] |

| Resources available to you | 43 | 92 | [79.6, 97.6] | 9 | 90 | [55.5, 99.8] |

| Care plan was very or critically important to help understand | ||||||

| Your diagnosis | 22 | 50 | [34.6, 65.4] | 9 | 90 | [55.5, 99.8] |

| Treatments you received | 28 | 61 | [45.4, 74.9] | 9 | 90 | [55.5, 99.8] |

| Tests needed in the future to detect recurrences or new cancers | 32 | 70 | [54.3, 82.3] | 10 | 100 | [69.2, 100] |

| Possible long-term and late effects | 28 | 60 | [44.3, 73.6] | 8 | 80 | [44.4, 97.5] |

| Resources available to you | 25 | 54 | [39, 69.1] | 8 | 80 | [44.4, 97.5] |

Number of subjects agreeing

Cl—confidence interval

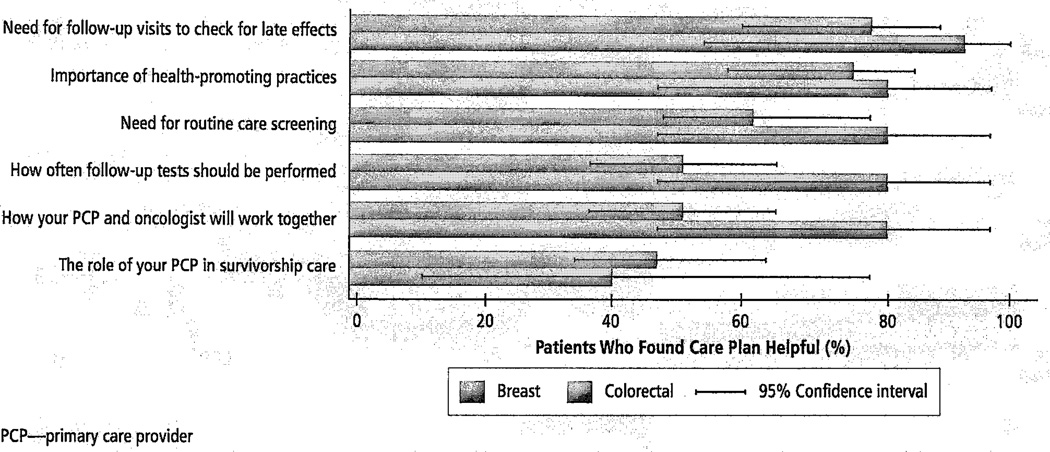

The helpfulness of specific aspects of the care plan was further evaluated in the survey (see Figure 1). Among patients with breast cancer, 36 (75%) reported that the care plan helped them better understand the need for follow-up visits to check for late effects and 35 (73%) reported that the care plan helped them better understand the importance of health-promoting practices following cancer treatment. For patients with breast cancer, the care plan was least helpful for understanding the frequency of follow-up tests (n = 25, 52%, found it helpful), how their primary care providers and oncologists will work together (n = 25, 52%), and the role of the primary care provider in their survivorship care (n = 24, 50%). Patients with colorectal cancer reported generally high levels of helpfulness for all elements, with the exception of their primary care providers' role in survivorship care (n = 4, 40%). The differences in those responses between patients with breast and colorectal cancer were not statistically significant. Analyses across facility type revealed that patients at the rural community hospital were more likely to find the care plan helpful in understanding how primary care providers and oncologists work together and the role of their primary care provider in survivorship care (n = 15 [71%] for both) than patients at the academic medical center (n = 18 [49%] and n = 13 [35%] patients, respectively) (p interaction = 0.1 and 0.03, respectively; data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Understanding Specific Elements of Care Through the Cancer Survivorship Plan (N = 58)

Discussion

The current study found that patients with breast or colorectal cancer in academic and rural study sites in Vermont reported high satisfaction with survivorship care plans designed using the Survivorship Care Plan Builder from Journey Forward. The care plans were rated very highly for usefulness, ease of understanding, and accuracy, and most patients reported that the care plan was very or critically important in helping them understand the various domains covered by the care plan. The results suggest that survivorship care plans are useful tools for improving patients' understanding of their diagnosis, treatment, survivorship care, and health promotion.

The area of the care plan that was least favorably rated was the information regarding the coordination of care. Only about half of the patients felt that the care plan helped them better understand the role of their primary care provider in survivorship care and how their primary care provider and oncologist would work together. The care plan was effective in describing the types of tests needed for surveillance for recurrences and new cancers, but a substantial proportion of patients still did not understand who would order tests for recurrences or new cancers. That limitation of the care plan likely reflects the uncertainty in the medical community regarding the precise roles of oncologists and primary care providers in survivorship care (Potosky et al, 2011). A survey by Salz et al. (2012) found that less than half of the survivorship care plans in use at National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers indicated the medical provider who should perform specific medical surveillance. In addition, the inclusion of contact information for care coordinators or navigators in survivorship care plans is rare (Strieker et al, 2011). The authors' results provide additional evidence that an urgent need exists for guidelines from professional societies and other organizations that can clarify the role of primary care providers and oncologists in survivorship care and reduce uncertainty for providers and patients.

Relationship to Previous Studies

The majority of previous studies regarding patient perspectives on survivorship care plans have used qualitative methods to assess patient preferences for survivorship care plans, most often by soliciting responses to a sample care plan (Salz et al., 2012). The studies provided evidence that survivors prefer the inclusion of information such as diagnosis and treatment, expected side effects (physical and psychological), signs and symptoms of recurrence, a recommended follow-up schedule, and resources for health promotion, further information, and support (Baravelli et al., 2009; Brennan, Butow, Marven, Spillane, & Boyle, 2011; Burg, Lopez, Dailey, Keller, & Prendergast, 2009; Hewitt, Bamundo, Day, & Harvey, 2007; Marbach & Griffie, 2011; Smith, Singh-Carlson, Downie, Payeur, & Wai, 2011). The current study provides quantitative evidence that breast and colorectal cancer survivors who receive a personalized survivorship care plan find value in those components of the care plan. The authors also found that cancer survivors considered the care plan visit highly useful. The results are consistent with prior studies suggesting that in-person care plan visits are generally positive experiences for patients and can reduce anxiety and stress related to cancer (Jefford et al., 2011; Mayer et al., 2012).

In contrast, the focus group studies indicated that patients believe that survivorship care plans would be valuable for improving communication among providers of care (Brennan et al., 2011; Kantsiper et al., 2009; Marbach & Griffie, 2011). The results suggest that current versions of survivorship care plans may not meet that goal.

The majority of previous studies regarding patient perspective on survivorship care plans have focused on patients with breast cancer. Unfortunately, the authors of the current article were unable to detect differences in care plan satisfaction between patients with breast and colorectal cancer because of the small number of patients with colorectal cancer enrolled in the current study.

Previous focus group studies have revealed no differences in preferences for care plan content among patients living in urban and rural settings (Smith et al., 2011). The authors of the current study observed few differences in patient evaluation of the care plan according to whether their care was received at an urban academic medical center or a rural community hospital, although those comparisons also were limited by a small sample. Patients at the community hospital were less likely to strongly agree that the care plan was easy to understand, but more than 90% indicated some level of agreement. Patients at the community hospital also found the care plan more important for understanding their diagnosis and for understanding how care would be coordinated. Some of the differences may be attributable to individual level factors such as income and health status, which were somewhat lower in the community hospital population. The results also could have been influenced by the style of delivery of the specific advanced practice providers at the two study sites.

Limitations

Certain limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of the current study. The lack of racial and ethnic diversity of patients seen at these clinics limits the generalizability of the results. Although the size of the study population was adequate to describe overall satisfaction with the care plans, insufficient power was available to detect small differences in responses by cancer type or type of facility. In addition, the participants who agreed to take part in the study were slightly younger than the target population of cancer survivors at the study clinics and may have differed in other unmeasured ways (e.g., attitudes toward medical care). Therefore, the findings require additional exploration in larger populations across a variety of healthcare settings.

Although the authors assessed patient satisfaction with the survivorship care plans at a single point in time, patient satisfaction with care plans may vary over time. The results should not be generalized to settings in which the document is not delivered during an in-person medical visit. Finally, responses to a series of questions regarding the helpfulness of the survivorship care plans will vary according to the quality of the care plan as well as the preexisting knowledge base of the patients. Although those questions provide a measure of the use of care plans in the patient population, the authors could not distinguish whether any lack of helpfulness was caused by a failure of the care plan document or simply because patients already possessed the knowledge.

Conclusion

Patients with breast and colorectal cancer were quite satisfied with the survivorship care plans and reported that the various components of the care plan were important in helping them understand their diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship care. Although the impact of survivorship care plans on health outcomes remains unclear, the results indicate that patients find them highly valuable. The survivorship care plans were most highly valued by patients for helping them understand the need for follow-up visits to check for late effects and the importance of health promoting practices following cancer treatment. Future efforts to improve survivorship care plans should focus on describing the coordination of survivorship care, including improved delineation of the specific roles of the primary care provider and oncologist.

Implications for Practice.

-

►

Survivorship care plans are useful tools for improving how patients with cancer understand their diagnosis, treatment, survivorship care, and health promotion.

-

►

Survivorship care plans partially reduce patient uncertainty regarding the coordination of survivorship care between primary care providers and oncologists.

-

►

Future efforts to ensure improved coordination of care will require improvements to current survivorship care plan designs and/or additional efforts beyond the provision of a survivorship care plan.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided through a grant by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5U48DP001935-02; SIP 10-029). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the article. The content of this article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is balanced, objective, and free from commercial bias.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Jennifer Hausman, MPH, and those at Journey Forward™ for their assistance in using the Survivorship Care Plan Builder, and Kathleen Howe, AA, Penelope Gibson, PA Janet Ely, APRN, Elizabeth McGrath, APRN, MSN, Amy Nolan, BS, Anne Dorwaldt, MA, Greg Dana, MPA, Dawn Pelkey, BA, and Rachael Chicoine, BS, for their assistance in the creation of the survivorship care plans, patient recruitment, data collection, and study support.

Footnotes

No financial relationships relevant to the content of this article have been disclosed by the independent peer reviewers or editorial staff.

Sprague can be reached at brian.sprague@uvm.edu, with copy to editor at CJONEditor@ons.org.

References

- Baravelli C, Krishnasamy M, Pezaro C, Schofield P, Lotfi-Jam K, Rogers M, Jefford M. The views of bowel cancer survivors and healthcare professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2009;3:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan ME, Butow P, Marven M, Spillane AJ, Boyle FM. Survivorship care after breast cancer treatment—Experiences and preferences of Australian women. Breast. 2011;20:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg MA, Lopez ED, Dailey A, Keller ME, Prendergast B. The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(Suppl. 2):S467–S471. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1012-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26:404–413. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Cancer. Cancer program standards 2012: Ensuring patient-centered care: American College of Surgeons. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA. Quality of life across the continuum of breast cancer care. Breast Journal. 2000;6:324–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2000.20042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, Maunsell E, Coyle D, Folkes A, Levine MN. Evaluating survivorship care plans: Results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:4755–4762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M. It's not over when it's over: Long-term symptoms in cancer survivors—A systematic review. International Journal of Psychiatry Medicine. 2010;40:163–181. doi: 10.2190/PM.40.2.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausman J, Ganz PA, Sellers TP, Rosenquist J. Journey Forward: The new face of cancer survivorship care. American Journal of Managed Care. 2011;17(5, Spec No.):e187–e193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, Harvey C. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: Qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:2270–2273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Cronin K. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2009. 2012 Retrieved from http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09.

- Jefford M, Lotfi-Jam K, Baravelli C, Grogan S, Rogers M, Krishnasamy M, Schofield P. Development and pilot testing of a nurse-led posttreatment support package for bowel cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing. 2011;34(5):E1–E10. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f22f02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantsiper M, McDonald EL, Geller G, Shockney L, Snyder C, Wolff AC. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: Perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(Suppl. 2):S459–S466. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marbach TJ, Griffie J. Patient preferences concerning treatment plans, survivorship care plans, education, and support services. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38:335–342. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EL, Gropper AB, Neville BA, Partridge AH, Cameron DB, Winer EP, Earle CC. Breast cancer survivors' perceptions of survivorship care options. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:158–163. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Smith SM, Mitby PA, Eshelman-Kent DA, Robison LL. Increasing rates of breast cancer and cardiac surveillance among high-risk survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma following a mailed, one-page survivorship care plan. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2011;56:818–824. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, Klabunde CN, Smith T, Aziz N, Stefanek M. Differences between primary care physicians' and oncologists' knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2011;26:1403–1410. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, Layne TM, Bach PB. Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2012 doi: 10.3322/caac.20142. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.3322/caac.20142/abstract;jsessionid=0C301A97375397C53E241603DDF1611D.d02t04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SL, Singh-Carlson S, Downie L, Payeur N, Wai ES. Survivors of breast cancer: Patient perspectives on survivorship care planning. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2011;5:337–344. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Snyder C. Is it time for (survivorship care) plan B? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:4740–4742. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11, Suppl.):2577–2592. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieker CT, Jacobs LA. Physical late effects in adult cancer survivors. Oncology (Williston Park) (Nurse Ed.) 2008;22(8 Suppl.):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strieker CT, Jacobs LA, Risendal B, Jones A, Panzer S, Ganz PA, Palmer SC. Survivorship care planning after the Institute of Medicine recommendations. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2011;5:358–370. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]