Abstract

Megakaryocytes exit from mitotic cell cycle and enter a phase of repeated DNA replication without undergoing cell division, in a process termed as endomitosis of which little is known. We studied the expression of a DNA replication licensing factor mini chromosome maintenance protein 7 (MCM7) and its intronic miR-106b-25 cluster during mitotic and endo-mitotic cycles in megakaryocytic cell lines and in vitro cultured megakaryocytes obtained from human cord blood derived CD34+ cells. Our results show that contrary to mitotic cell cycle, endomitosis proceeds with an un-coupling of the expression of MCM7 and miR-106b-25. This was attributed to the presence of a transcript variant of MCM7 which undergoes nonsense mediated decay (NMD). Additionally, miR-25 which was up regulated during endomitosis was found to promote megakaryopoiesis by inhibiting the expression of PTEN. Our study thus highlights the importance of a transcript variant of MCM7 destined for NMD in the modulation of megakaryopoiesis.

Keywords: megakaryopoiesis, polyploidy, MCM7, miRNA, Nonsense mediated decay, PTEN

Abbreviations

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

- FACS

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting

- HPRT

Hypoxanthine PhosphoRibosyl Transferase

- APC

Allophycocyanin

- PE

R-phycoerythrin

- RIPA

Radio immuno precipitation Assay

Introduction

Megakaryopoiesis is the process of formation of large megakaryocytes which ultimately leads to production of functional platelets, crucial in the regulation of hemostasis and blood coagulation. Given the enormous importance of platelets, efforts are on to increase its production after bone marrow transplantation and/or chemotherapy. Committed megakaryocyte progenitors initially divide by the process of mitosis. Later stages of megakaryocytic differentiation involve a shift form mitotic cycle to repeated rounds of DNA synthesis without cell division, in a process termed as endomitosis. This progression is characterized by a corresponding failure of karyokinesis and cytokinesis.1,2 Although a direct correlation between polyploidy and platelet production has been observed,3-5 significantly little is known regarding the regulation of endomitosis.

Previous studies have shown that polyploidy is associated with changes in the expression of various genes belonging to multiple cellular pathways such as DNA replication, transcription and apoptosis.6,7 In cells undergoing mitotic cell division cycle, various DNA replication licensing factors regulate the firing of replication. One of the major DNA replication licensing factors is the Mini Chromosome Maintenance protein complex (MCM) which consists of MCM2–7.8 Prior to DNA replication MCM2–7 forms the pre-replication complex (pre-RC). After being loaded on to the origin recognition complex (ORC) at the origin of replication, it subsequently leads to initiation of replication. Thereafter, phosphorylation of the pre-RC during S-phase by cyclin dependent kinases results in dissociation of the MCM complex which ensures that the same origin does not fire again in the same mitotic cell cycle.9,10 Of the 6 MCM proteins of the pre-RC complex, only MCM7gene locus also codes for an important microRNA cluster (miR-106b-25). Around 50% of the mammalian miRNAs are located within introns or exons of protein-coding genes and on the same strand. Most of these same-strand intragenic miRNAs are located within introns of host genes and are referred to as intronic miRNAs.11,12

We therefore sought to investigate the effects of endomitosis on the expression of MCM7 and its intronic miRNA cluster. Our results revealed that unlike mitotic cell division where MCM7 and miR-106b-25 are co-expressed, surprisingly endomitosis proceeds with an un-coupling of their expression. Further, a second transcript variant of MCM7 was found. This transcript was observed to undergo NMD and thus contributed to the increased expression of miR-106b-25 without a simultaneous increase in expression of MCM7. Moreover, miR-25 was found to promote megakaryopoiesis by inhibiting PTEN. Our study thus reveals a crucial role of the MCM7 transcript designed for NMD during the progression of megakaryopoiesis.

Results

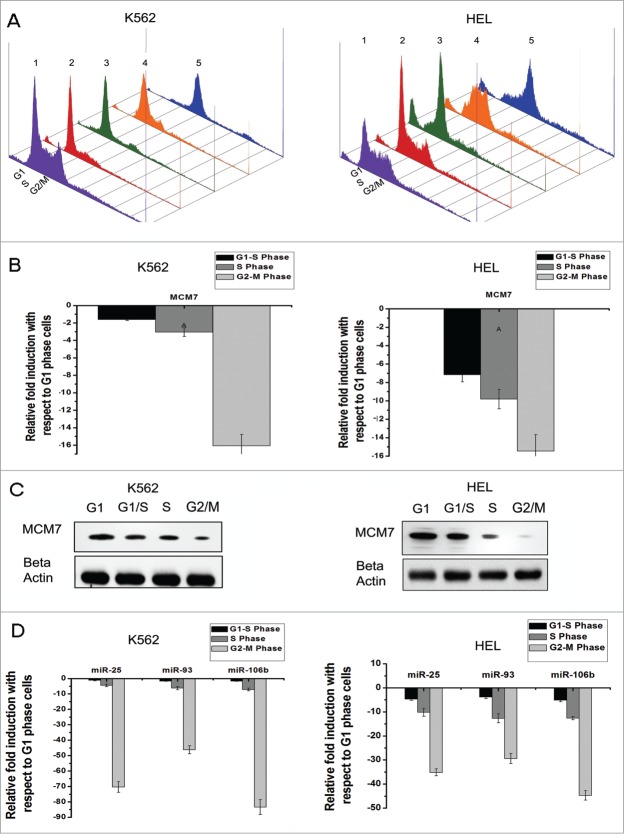

Co-transcription of MCM7 and its intronic miR-106b-25 cluster during mitotic cell cycle of megakaryocytic cell lines

In order to study the effects of cell cycle progression on the expression of MCM especially MCM7, we analyzed their expression at different phases of cell cycle in megakaryocytic cell lines (K562, HEL and CMK). Synchronized cell populations from the 4 phases of cell cycle (G1, G1/S, S, and G2/M) were used to study the transcript levels of MCM7 (Fig. 1A). Our results revealed a cyclic pattern of expression with maximum expression observed in the G1 and G1/S phases of cell cycle which gradually decreased during progression through S and G2/M phases (Fig. 1B and C, Supplementary information S1C). Furthermore, the cell lines showed similar expression pattern of MCM7 at the protein level (Fig. 1C, Supplementary information S1A, S1B). Moreover, MCM7 is known to harbour an intronic miRNA cluster (miR-106b-25). The expression of miR-106b-25 was therefore checked during the cell cycle progression of HEL and K562 cells. Similar to the expression pattern observed with MCM7, the miR-106b-25 cluster also showed maximal expression in G1 and G1/S phases of cell cycle (Fig. 1D, Supplementary information S1C). Our data thus shows that both MCM7 and its intronic miR-106b-25 cluster are co-transcribed during mitotic cell division.

Figure 1 (See previous page).

Co-transcription of MCM7 and its intronic miR-106b-25 cluster during cell cycle (A) K562 and HEL cells were synchronised with hydroxyurea (HU, G1/S phase blocker) and nocodazole (G2/M phase blocker) and subsequently released from block. After 4 hours, cells released from HU induced block entered the S phase whereas cells released from nocodazole entered the G1 phase of the cell cycle. All cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and subjected to FACS analysis to check the cell cycle phases. The representation shows cells in various phases of cell cycle where the numbers represent: (1) asynchronous cells, (2) G1 phase (3) G1/S phase (4) S phase and (5) G2/M phase of cell cycle. (B) Relative gene expression of MCM 7 at different phases of cell cycle normalized against HPRT1 as seen by qRT-PCR. Data represents the mean ± s.e.m of 3 independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.03, ***P < 0.005, n = 3) in K562 and HEL cells. (C) Western blot of whole cell lysate of HEL and K562 cell lines at the indicated phases of cell cycle showing the expression of MCM7. Densitometric analysis of the blot shows the mean ± s.e.m of 3 individual experiments. Beta Actin was used as a loading control. (D) Relative gene expression of miR-106b-25 cluster at different phases of cell cycle normalized against HPRT1 as seen by qRT-PCR. Data represents the mean ± s.e.m of 3 independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.002, *****P < 0.001, n = 3) in K562 and HEL cells.

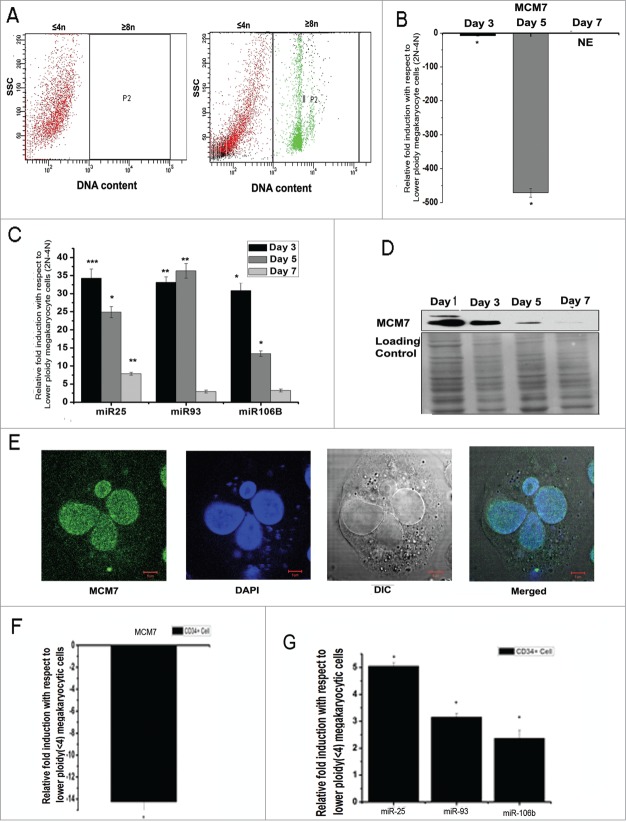

Differential expression of MCM7 and its intronic miRNA cluster during endomitosis

In order to determine the relative expression of MCM7 and its intronic miRNA cluster during the later stages of megakaryopoiesis which is characterized by a predominant endo-mitotic DNA replication cycle, the HEL cells were subjected to TPA followed by analysis of their DNA content. The presence of polyploidy HEL cells was detected on day 3 of culture and followed till day 7. The HEL cells were sorted based on their DNA content on day 3, 5 and 7 where cells with 2N-4N DNA content were sorted into one chamber and polyploidy cells (≥8 N) were sorted into another chamber (Fig. 2A). The 2 populations thus obtained were analyzed for the expression of MCM7 and the intronic miR-106b-25 cluster. MCM7 expression was found to be down regulated in the higher polyploid cells when compared to 2N-4N subpopulation (Fig. 2B). Surprisingly, miR-106b-25 cluster was found to be significantly upregulated in higher polyploid cells (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the expression of MCM7 was also observed to decrease progressively in unsorted HEL cells when subjected to TPA (Fig. 2D, Supplementary information S2A). The polyploid cells were however found to retain nuclear MCM7 (Fig. 2E). To further verify the above observation we have examined the expression of MCM7 and miR-106b-25 in CMK cell line and have found similar results (Supplementary information S2F, G). We also checked the MCM7 promoter activity during TPA induced differentiation of HEL cells. Dual luciferase assay with empty or MCM7 promoter coded luciferase reporter containing vector rather showed a 2-fold increase in the promoter activity after megakaryocytic induction with TPA (Figure Supplementary information S2B) suggesting transcription of MCM7. To further verify whether the differential expression of MCM7 and its intronic miR-106b-25 cluster was a general phenomenon associated with polyploid megakaryocytes, CD34+ cells isolated from cord blood (CB) and bone marrow (BM) were subjected to in vitro uni-lineage megakaryopoietic culture. The megakaryocytes obtained on day 10 (CD61+CD42b+) were sorted based on their DNA content13,14 (Supplementary information S2D). Similar to HEL cells, in vitro cultured primary polyploid megakaryocytes also showed a pronounced down regulation of MCM7 (Fig. 2F, Supplementary information S2E). Additionally, miR-25 was significantly up regulated in the higher polyploid (≥8N) megakaryocytes (Fig. 2G, Supplementary information S2E). Interestingly, neither MCM7 nor its intronic miR-106b-25 cluster showed any significant change in their expression in the unsorted day 10 in vitro cultured megakaryocytes when compared to day 0. This indicated that the changes observed in the expression of MCM7 and miR-106b-25 was specifically induced by endomitosis. In order to check whether the upregulation of miR-106b-25 cluster was specific to this cluster, we also investigated the expression of a related miR-17–92 cluster and miR106a which is an isoform of miR-106b. miR-106a expression was observed to remain unchanged during differentiation. Also, miR-17–92 cluster was found to remain unchanged or in some cases only moderate changes in expression levels were detected. However, unlike miR106b-25 cluster, no clear pattern in regulation of miR-17–92 cluster could be seen (Figure Supplementary information S2C). Thus, megakaryocytic endo-reduplication was found to proceed by a general down regulation of MCM7. However, miR-106b-25 cluster was upregulated in polyploid megakaryocytes.

Figure 2 (See previous page).

Differential expression of MCM7 and miR-106b-25 cluster (A) HEL cells subjected to TPA for 5 d were stained with vibrant orange and sorted under flow cytometer. The left panel shows uninduced HEL cells with only 2N-4N DNA content while the right panel shows polyploid HEL cells induced with TPA. The P2 gated cells on the right panel were sorted from the bulk population. (B) Relative gene expression of MCM7 in ≥8 N population when compared to 2N-4N population as seen by qRT-PCR. The relative expressions were normalized against HPRT1. Data represents the mean ± s.e.m of 3 independent experiments (*P < 0 .03, n = 3) in HEL cells. (C) Relative gene expression of miR-106b-25 cluster in ≥8 N population when compared to 2N-4N population as seen by qRT-PCR. The relative expressions were normalized against HPRT1. Data represents the mean ± s.e.m of 3 independent experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.03, ***P < 0.005, n = 3) in HEL cells. (D) Western blot of whole cell lysate of HEL cells treated with TPA for the indicated time points in days showing the expression of MCM7. Densitometric analysis of the blot has been provided in supplementary information S2 .Whole membrane coomassie staining was used as a loading control. (E) HEL cells treated with TPA for 72 hrs were stained with anti-MCM7 antibody and DAPI. The nuclear localization of MCM7 is seen in a polyploid HEL cell. (F, G) Relative qRT-PCR expression of MCM7 and miR-106b-25 cluster in in vitro unilineage megakaryocyte culture from bone marrow derived CD34+ cells, higher ploidy ≥8 N population were compared to 2N-4N population in Day 10. The relative expressions were normalized against HPRT1. Data represents mean ± s.e.m of 3 independent experiments (*P < 0 .05, n = 3).

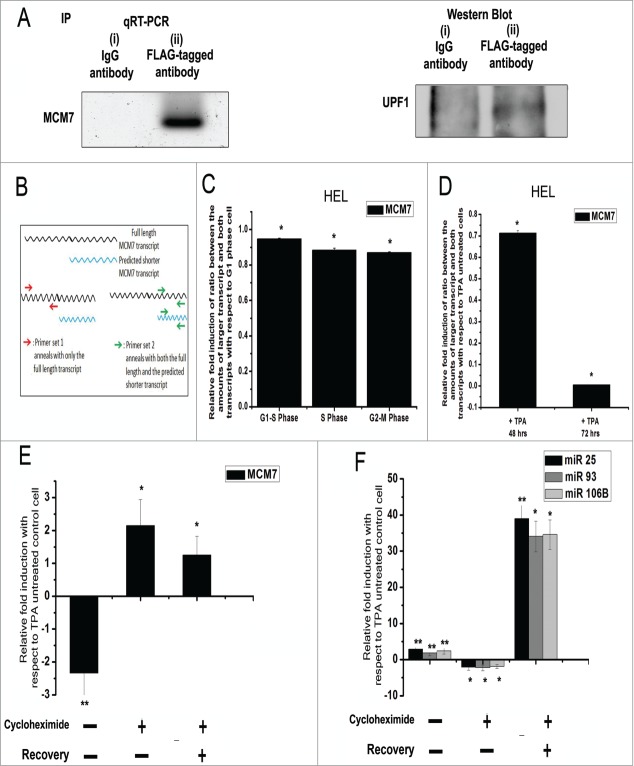

Nonsense mediated decay of MCM7 transcript variant during megakaryocytopoiesis

To understand the mechanism by which megakaryopoietic polyploidy induces a differential expression of MCM7 and its intronic miRNA cluster, the genomic sequence of MCM7 was scanned for putative internal RNA polymerase binding sites. However, no such sequence was found near the miR-106b-25 cluster (13th intron) in the UCSC Genome Browser, thus ruling out the possibility of MCM7 gene independent transcription. Interestingly, ENSEMBL human genome browser predicts a second transcript variant of MCM7 which undergoes NMD. To verify the existence of such a theoretically proposed transcript variant of MCM7 which also undergoes NMD, HEL cells were transfected with Flag-UPF1 encoding vector. UPF1 is a key player of the exon junction complex and plays crucial role in mRNA surveillance and NMD.15 FLAG-UPF1 was immuno-precipitated from these transfected cell lysates and the immunoprecipitate was analyzed for the presence of UPF1 complex bound MCM7 transcript indicating the presence of MCM7 mRNA within the UPF1 complex (Fig. 3A). To check whether the full length MCM7 transcript and the transcript undergoing NMD are themselves differentially regulated during cell cycle and endomitosis, we have used 2 sets of primers among which one set anneals with only the full length transcript of MCM7 while the other more internal primer set anneals with both the full length and the predicted shorter transcripts (Fig. 3B). Using qRT-PCR, we then detected the amount of full length MCM7 transcript and both the full length and shorter transcripts in the same sample by standard curve method. The difference between the 2 Ct values clearly defines the existence of the 2 transcripts. We then compared the ratio between the amounts of full length MCM7 transcript and both the full length and the short transcripts in different stages of HEL cell cycle; quantitative result indicates the expression levels of the 2 transcripts do not vary during cell cycle progression (Fig. 3C). However, in the higher polyploid HEL cells the ratio decreases and so does the relative fold change value with respect to lower ploidy cells. Indeed, the expression of full length transcript decreases in higher polyploid cells, while the expression of total transcripts remains same indicating increased production of the second smaller variant (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

NMD of MCM7 transcript variant in HEL cells. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of MCM7 specific qRT-PCR product synthesized from (i) anti-IgG antibody precipitate (ii) anti-FLAG antibody precipitate. Western blot of (i) anti-IgG antibody precipitate (ii) anti-FLAG antibody precipitate. (B) Schematic representation of the 2 MCM7 transcripts and respective primer annealing position for quantitative assays. (C) Relative fold change of ratio between the amounts of full length transcript and the total transcripts in cell cycle phases as compared to G1 phase. Data represents the mean ± s.e.m of 3 independent experiments (*P < 0 .05, n = 3). (C) Relative fold change of ratio between the amounts of full length transcript and both the transcripts in higher ploidy (>8 N) vis a vis lower ploidy (2N-4N). Data represents the mean ± s.e.m of 3 independent experiments (*P < 0 .05, n = 3). (D) Relative expression of MCM7 in cells subjected to the indicated treatments, compared to untreated cells. Cells were differentiated in the presence of TPA for 48 hr followed by treatment with/without cycloheximide. Cycloheximide treated cells were then allowed to recover in media with TPA only for a further 24hr. Data represents the mean ± s.e.m of 3 independent experiments (*P < 0 .01, **P < 0 .005, n = 3) normalized against HPRT1.

To investigate further whether MCM7 transcripts undergo NMD, the cells were exposed to the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, previously shown to inhibit NMD.16 HEL cells were subjected to TPA for 48 hours followed by cycloheximide for 6hrs. Following the treatment, the cells were again allowed to recover in media with TPA only for an additional 24hr. As expected, treatment with cycloheximide blocks NMD and leads to an up regulation of MCM7 transcript when compared to cells treated with TPA alone (Fig. 3E). We next checked the expression of miR-106b-25 cluster in the cycloheximide treated cells. As observed previously, miR-106b-25 cluster was up regulated following TPA treatment. Addition of cycloheximide effectively inhibited the synthesis of all 3 miRNAs leading to a net down regulation of miR-106b-25 cluster. Removal of cycloheximide from the medium followed by culture of these cells for an additional 24 hr in the presence of TPA lead to a pronounced up regulation of miR-106b-25 cluster expression with a concomitant up regulation of MCM7 (Fig. 3F). In order to exclude pleiotropic effects of cycloheximide on miRNA/MCM7 expression, shRNA to UPF1 was used to block NMD.17 HEL cells were initially subjected to TPA for 48 hours to induce megakaryopoiesis, followed by transfection with sh-UPF1 plasmid for a transient period of 48 hrs. Like cycloheximide treatment, sh-UPF1 also leads to an up regulation of MCM7 transcript and a down regulation of miR-106b-25 cluster (Supplementary information S3A) when compared to cells treated with TPA alone. Moreover, we also checked the ratio between the amount of full length transcript and that of total transcripts in 48 hrs TPA treated HEL cells as well as in cells treated with TPA for 48 hrs followed by 6hr cycloheximide treatment. Compared with TPA untreated HEL cells, the relative fold induction shows that the ratio decreased in 48hr TPA treatment but increased due to cycloheximide treatment (Supplementary information S3B). Thus, our experimental data clearly vindicated the production of the second theoretically predicted variant of MCM7. Furthermore, NMD was found to regulate the expression of miR-106b-25 cluster during megakaryopoiesis.

miR-25 promotes megakaryopoiesis

As the expression of miR-106b-25 cluster increased during megakaryopoiesis, we investigated whether the cluster had any role in lineage specification. To find out the effects of intronic miR-106b-25 cluster, empty vector or vectors encoding miR-25, miR93 and miR106b were transfected individually into HEL, K562 cells and cord blood CD34+. miR-25 transfected cells showed significant increase in the expression of megakaryocytic markers CD61 and CD42b (Fig. 4 A,B and Table 1, 2) whereas anti-miR25 transfected HEL cells showed a decrease in the expression of megakaryocytic marker CD42b (Fig. 4C). However, no significant change in the expression of CD61 and CD42b was observed in the cells transfected with miR106b and miR93 (Supplementary information S4A, S4B and S4C). Further, we checked the transcript levels of some megakaryocytopoiesis specific transcription factors (FOG1, Fli1, and NF-E2) in miR-25 or anti-miR25 transfected HEL and K562 cells. All 3 transcription factors were found to be significantly up-regulated in miR25 transfected cell (Fig. 4D) with similar results in K562 (Supplementary information S5A) cell line. Expression of Fli1, and NF-E2 were significantly downregulated upon treatment with anti-miR25 in HEL cell line (Supplementary information S5B). These data suggests that miR-25 regulates megakaryopoiesis in megakaryocytic cell lines. To elucidate the function of miR-25 during megakaryopoiesis, the expression of a known miR-25 target – Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)18 was checked. Both miR-25 transfected HEL as well as K562 cells showed decreased expression of PTEN (Fig. 4E) whereas anti-miR25 transfected HEL cells shows increased expression of PTEN (Fig. 4F). To further confirm that miR-25 induced changes in megakaryopoiesis were modulated by down regulation of PTEN, K562 and HEL cells were transfected with either PTEN or miR-25 alone or in a combination of both PTEN and miR-25. Results show that expression of PTEN could reverse the observed increase in the expression of CD42b in cells transfected with miR-25 (Table 3, Supplementary information S6C). Additionally, PTEN is known to negatively regulate AKT a master regulator of megakaryopoiesis. We therefore checked the phosphorylation of AKT which was also found to increase in miR-25 transfected cell lines (Fig. 4E, Supplementary information S5C). Moreover, a gradual down-regulation of PTEN expression was observed in HEL and K562 cell lines upon treatment with TPA in concert to the increasing percentage of polyploid cells (Fig. 4G, Supplementary information S5D). Thus miR-25 was found to positively regulate megakaryopoiesis.

Figure 4.

miR-25 promotes megakaryopoiesis (A) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of CD42b and CD61 in mock transfected and miR-25 transfected HEL and K562 cells. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of CD42b and CD61 in mock transfected and miR-25 transfected human CD34+ cells. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of CD42b in scrambled siRNA transfected and anti-miR25 transfected HEL cells. (D) Relative gene expression of megakaryopoietic lineage specific transcription factors in miR-25 transfected HEL cells as compared to mock transfected cells. Data represents the mean ± s.e.m of 3 independent experiments (*P < 0 .05, n = 3) normalized against HPRT1. (E) Western blot of whole cell lysates of HEL and K562 cells transfected with mock vector or miR-25 coding vector. Densitometric analysis of the blot has been provided in supplementary information S4C. Beta actin was used as a loading control. (F) Western blot of whole cell lysates of HEL cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or anti miR-25. Densitometric analysis of the blot has been provided in supplementary information S4D. Beta actin was used as a loading control. (G) Western blot of whole cell lysates of HEL and K562 cells treated with TPA for the indicated time points in days showing the expression of PTEN. Densitometric analysis of the blot has been provided in supplementary information S4E. Whole membrane coomassie staining was used as a loading control.

Table 1.

CD42b and CD61 expression in HEL cells.

| HEL | ||

|---|---|---|

| Transfected with | Median intensity value of CD61(±SE ) | P-value |

| Mock | 9.62(±0 .0692) | 0.0089 |

| miR-25 | 14.51(±0 .0088) | 0.005 |

| Transfected with | Median intensity value of CD42b(±SE ) | P-value |

| Mock | 192(±0 .3199) | 0.0001 |

| miR-25 | 235.59(±0 .828) | 0.0038 |

Table 2.

CD42b and CD61 expression in K562 cells

| K562 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Transfected with | Median intensity value of CD61(±SE ) | P-value |

| Mock | 29.25(±0 .3101) | 0.04 |

| miR-25 | 45.4(±1 .79) | 0.0113 |

| Transfected with | Median intensity value of CD42b(±SE ) | P-value |

| Mock | 123.93(±0 .2466) | 0.004 |

| miR-25 | 304.24(±1 .78) | 0.0057 |

Table 3.

CD42b expression in HEL cells

| HEL | ||

|---|---|---|

| Transfected with | Median intensity value of CD42b(±SE ) | P-value |

| Mock | 239.72 (± 8.90822) | 0.00001 |

| miR-25 | 309.38667 (±4 .76545) | 0.00001 |

| PTEN | 125.46 (±3 .0291) | 0.00001 |

| PTEN and miR-25 | 286.75333 (±7 .3443) | 0.00001 |

Discussion

Megakaryopoiesis results in definitive morphological and functional changes within the differentiating cells leading to establishment of large polyploid megakaryocytes.19 However, the regulation of such a complex process remains largely unknown. Therefore, we endeavored to study the regulation of a key factor required for initiation of DNA replication- MCM7. The MCM7 gene locus is unique due to the presence of a miRNA cluster (miR-106b-25) within its 13th intronic region.18 Our results show that MCM7 and its intronic miRNA cluster show a cyclic pattern of expression during mitotic cell division cycle in megakaryocytic cell lines (K562, HEL and CMK). It may be worthwhile to mention that a similar trend in the regulation of MCM7 and its intronic miRNA cluster was also reported during mitotic cell division of a gastric cancer cell line.20 Co-expression of MCM7 and miR-25 was reported even during B cell development.21 Surprisingly, endo-mitotic cycle in polyploid megakaryocytes altered this co-regulation of MCM7 and miR-106b-25 cluster. Polyploid megakaryocytes showed pronounced down regulation of MCM7. At the same time, these cells were found to harbour significantly increased expression of miR-106b-25 cluster. Importantly, MCM7 was previously shown to be down regulated in polyploid human and murine megakaryocytes, thus corroborating our finding.6,7 Moreover, these previous studies have further suggested a general down regulation of DNA replication machinery in polyploid megakaryocytes.

We therefore tried to determine how endomitosis may contribute to the differential expression of MCM7 and its intronic miRNA cluster. The ENSEMBL data base reports a theoretically predicted transcript variant of MCM7 that undergoes NMD. The presence of this transcript that may also undergo NMD was therefore investigated. Our results revealed the presence of a second transcript variant of MCM7 within UPF1 containing complex. Further using cycloheximide and sh-UPF1 to block NMD, we were able to show that NMD does regulate the transcript levels of both MCM7 and its intronic miRNA cluster. Such a functional link between NMD and uncoupling of host gene and its intronic miRNA cluster has been documented recently for myosin heavy chain (MYH7b) and its intronic miR499.22 The exact mechanism behind this phenomenon is unknown. However, uncoupling of several mRNA surveillance mechanisms like NMD, NAS etc. may probably be involved.23 Interestingly, inhibition of UPF1 (a crucial NMD factor) by sh-UPF1 also showed similar pattern of expression of MCM7 and miR-106b-25 indicating that the results obtained are specifically linked to inhibition of NMD and not due to any off-target effects of cycloheximide. When we investigated the ratio between amounts of full length transcript of MCM7 and total MCM7 transcripts, we observed a clear down regulation of the full length transcript during megakaryocytic endomitosis, whereas this ratio remained unchanged during the different phases of cell cycle. Corresponding to this data, we also observed a 2 fold increase in the promoter activity of MCM7 during TPA induced differentiation. Given the observed increase in the expression of miR-106b-25 cluster in polyploid megakaryocytes, we next checked whether the cluster itself could modulate megakaryopoiesis. Of the 3 miRNAs present in the cluster, only miR-25 could significantly upregulate the megakaryopoietic surface markers (CD61 and CD42b) as well as lineage specific transcription factors (FOG1, Fli1 and NFE2). Interestingly, the expression of miR-25 was reported to be invariant during TPA induced differentiation of K562 cells.24 However, this study looked into unsorted (containing both diploid and polyploid) populations. Thus, it appears that polyploidization and not just megakaryopoietic differentiation induces up regulation of miR-25. In support of this hypothesis, we found that unsorted megakaryocytes obtained from in vitro cultured cord blood CD34+ stem and progenitor cells did not show any significant change in the expression of miR-106b-25.

One of the known targets of miR-25 is PTEN.18 Incidentally, PTEN is a known tumor suppressor protein that plays an important role during mitotic cell cycle.25 Furthermore, loss of PTEN in mice resulted in increased production of megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors along with an increase in megakaryocyte colony forming unit.26 Our results also show a gradual decrease in the expression of PTEN during megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 and HEL cells. Further, miR-25 transfected cells also showed decreased expression of PTEN along with a corresponding increase in the phosphorylation of Akt.

In conclusion, the expression of MCM7 and its intronic miR-106b-25 cluster was found to be uncoupled during megakaryopoietic endomitosis. Furthermore, upregulation of miR-25 in polyploid megakaryocytes was found to contribute toward megakaryopoiesis by direct inhibition of PTEN. This is the first report that not only establishes the presence of a second transcript variant of MCM7 that undergoes NMD but also implicates it to the uncoupling of MCM7 and miR-106b-25 transcription. Given the known roles of MCM7, PTEN and miR-25 in cancer,27-30 it would be interesting to see whether deregulated megakaryopoiesis is also associated with a corresponding deregulation of this gene locus.

Experimental Procedures

Isolation of CD34+ cells from cord blood/bone marrow and unilineage megakaryocyte culture

Isolation of CD34+ cells from cord blood/bone marrow was done using the protocol.31 Unilineage megakaryocyte cultures were initiated from freshly isolated CD34+ cells in IMDM supplemented with 10%BIT Serum (Stem cell technologies Inc..) and cytokines. Cytokines used for the first 2 d of culture include 10 μg/ml TPO and 50 μg/ml SCF. Thereafter, cells were maintained in 10 ng/ml TPO. Megakaryocyte population was sorted at day 10 (CD61+CD42b+) of in vitro culture in a FACS Aria II system (BD Biosciences).13,14 All clinical samples were collected under consent following strict institutional ethical guidelines.

Cell lines and culture conditions

CMK, K562 and HEL cells were cultured in RPMI1640 (Gibco, California, USA) with 10% FBS (Gibco, California, USA). To analyze the cells at various phases of cell cycle, the cells were synchronized using 1 μM hydroxyurea and 10 ng/ml nocodazole (for HEL) or 20 ng/ml (for K562) for 16–18 hour and subsequently cultured in fresh media without the cell cycle blocking agents. Progression through the cell cycle was followed by FACS analysis. To induced megakaryopoietic lineage differentiation K562 and HEL cells were subjected to 50 nM and 10 nM of 12-O-Tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA) respectively. HEL cells differentiated with TPA were subjected to 50 μg/ml cycloheximide for 6 hrs. The cells were thereafter maintained in fresh media without the inhibitors for an additional 24 hrs. Details of the various plasmids used may be found in Supplementary methods S2. Cell lines were transfected with various plasmids using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Flow Cytometric analysis

For cell-cycle analysis cells were analyzed for DNA content after staining with Propidium iodide or vibrant orange (Invitrogen) on a BD FACS Calibur platform (California, USA). Megakaryocytic cells stained with vibrant orange were sorted based on their DNA content on BDFACS Aria II platform.

RNA extraction and Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Tripure isolation reagent (TRIZOL, Roche, Germany).Subsequently, 200 ng RNA was then reverse transcribed using cDNA synthesis kit (Roche, Germany). The expression level of genes was assessed by quantitative RT-PCR using SYBR Green core PCR reagents (Applied Biosystems, California, and USA). HPRT1 was used to normalize the expression of the genes. The reactions were carried out in 7500 Sequence Detection Systems (Applied Biosystems). Details of the primer sequence are given in the supplementary methods S1.

Western blotting

For western blotting, cells were harvested and lysed in cold RIPA buffer. Equal amounts of protein was run on parallel lanes of SDS PAGE and blotted on PVDF membrane (GE Amersham, UK). Following incubation with primary and HRP conjugated secondary antibodies, the blots were developed using Enhanced Chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fischer Scientific Pierce, IL, and USA).Antibodies against MCM7 obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (California, USA). APC conjugated CD42b, PE conjugated CD61 and PE conjugated CD34 was purchased from BD Biosciences.

Detection of MCM7 transcript variant by immunoprecipitation of Flag-UPF1 containing complex

pCI-neo-FLAG-UPF1 vector was transfected into HEL cells (with transfection efficiency >70 %). The Flag-UPF1 complex was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and the presence of MCM7 mRNA was checked in the resulting immunoprecipitate according to previously published protocol.32 In brief, 2 d after transfection, cells were harvested and lysed in ice-cold NET-2 buffer (50 mM, Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 300 mM NaCl, 0.05% NP-40, 100U RNAse inhibitor, 10mM Vanadyl ribonucleoside complex). Protein A/G bead cleared lysates were incubated with either anti-FLAG antibody or IgG control antibody, Followed by addition of protein A/G beads. The immunoprecipitate obtained was washed 6 times with NET-2 buffer and the immunoprecipitate was thereafter checked for the presence of FLAG-UPF1 (through protein gel blotting) and MCM7 transcript (through RT-PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis).

Statistical Analysis

Results of experiments are expressed as mean ± SE. Student's 2 tailed t test was used to compare mean of test and control samples.

Confocal Microscopy

Cells were processed according to previously published protocol.33 Cells were stained with anti-MCM7 antibody followed by Alexa 488- tagged secondary antibody. Cells were then stained with DAPI and imaged under confocal mode in a Carl Zeiss LSM 510 Meta microscope.

Detection of promoter activity in polyploid megakaryocytic cells by Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay

Empty or MCM7 promoter coded luciferase reporter containing vector were transfected into HEL cells, followed by TPA treatment for different time points. The expression of the firefly luciferase was quantified with a Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega Corporation, Madison,WI) according to the manufacturer's protocol. All transfections were performed in triplicate. The level of the firefly luciferase activity was normalized by the corresponding level of the Renilla luciferase activity and the values for the negative control were normalized. Luminescence was measured using a Sirius Luminometer, Berthold detection systems (USA).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

Plasmid encoding Flag-UPF1 was a kind gift from Dr. Lynne E. Maquat. Plasmid encoding sh-UPF1 was a gift from Dr. Lawrence B. Gardner and plasmid encoding wild type MCM7 promoter was generously supplied by Dr. Tohru Kiyono and CMK cells obtained from Dr. William Vainchenker's lab. Cord blood samples were collected after institutional ethical clearance and informed consent from M.R. Bangur Hospital, Kolkata, India.

Funding

This work has been funded by the Integrative Biology on Omics Platform (IBOP) project of Department of Atomic Energy, Government of India.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1. Lordier L, Jalil A, Aurade F, Larbret F, Larghero J, Debili N, Vainchenker W, Chang Y. Megakaryocyte endomitosis is a failure of late cytokinesis related to defects in the contractile ring and Rho/Rock signaling. Blood 2008; 112(8): p. 3164-74; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lordier L, Pan J, Naim V, Jalil A, Badirou I, Rameau P, Larghero J, Debili N, Rosselli F, Vainchenker W, et al. , Presence of a defect in karyokinesis during megakaryocyte endomitosis. Cell Cycle 2012; 11(23): p. 4385-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.22712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mattia G, Vulcano F, Milazzo L, Barca A, Macioce G, Giampaolo A, Hassan HJ. Different ploidy levels of megakaryocytes generated from peripheral or cord blood CD34+ cells are correlated with different levels of platelet release. Blood 2002; 99(3): p. 888-97; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood.V99.3.888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miyazaki R, Ogata H, Iguchi T, Sogo S, Kushida T, Ito T, Inaba M, Ikehara S, Kobayashi Y. Comparative analyses of megakaryocytes derived from cord blood and bone marrow. Br J Haematol 2000; 108(3): p. 602-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01854.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vyas P, Ault K, Jackson CW, Orkin SH, Shivdasani RA. Consequences of GATA-1 deficiency in megakaryocytes and platelets. Blood 1999; 93(9): p. 2867-75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen Z, Hu M, Shivdasani RA. Expression analysis of primary mouse megakaryocyte differentiation and its application in identifying stage-specific molecular markers and a novel transcriptional target of NF-E2. Blood 2007; 109(4): p. 1451-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2006-08-038901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raslova H, Kauffmann A, Sekkaï D, Ripoche H, Larbret F, Robert T, Le Roux DT, Kroemer G, Debili N, Dessen P, Lazar V, et al. , Interrelation between polyploidization and megakaryocyte differentiation: a gene profiling approach. Blood 2007; 109(8): p. 3225-34; PMID:17170127; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2006-07-037838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Labib K, Tercero JA, Diffley JF. Uninterrupted MCM2-7 function required for DNA replication fork progression. Science 2000; 288(5471): p. 1643-7; PMID:10834843; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.288.5471.1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maiorano D, Lutzmann M, Mechali M. MCM proteins and DNA replication. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2006; 18(2): p. 130-6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kearsey SE, Maiorano D, Holmes EC, Todorov IT. The role of MCM proteins in the cell cycle control of genome duplication. Bioessays 1996; 18(3): p. 183-90; PMID:8867732; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.950180305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rodriguez A, Griffiths-Jones S, Ashurst JL, Bradley A. Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res 2004; 14(10A): p. 1902-10; PMID:15364901; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.2722704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Monteys AM, Spengler RM, Wan J, Tecedor L, Lennox KA, Xing Y, Davidson BL. Structure and activity of putative intronic miRNA promoters. RNA 2010; 16(3): p. 495-505; PMID:20075166; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.1731910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roy A, Lahiry L, Banerjee D, Ghosh M,Banerjee S. Increased Cytoplasmic Localization of p27kip1 and Its Modulation of RhoA Activity during Progression of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. PLoS One 2013; 8(10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sengupta A, Banerjee S. Pleiotropic p27(Kip1), BCR-ABL and leukemic stem cell: the trio in concert. Leukemia 2007; 21(12): p. 2559-61; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.leu.2404842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maquat LE, Serin G. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: insights into mechanism from the cellular abundance of human Upf1, Upf2, Upf3, and Upf3X proteins. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2001; 66:p. 313-20; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/sqb.2001.66.313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carter MS, Doskow J, Morris P, Li S, Nhim RP, Sandstedt S, Wilkinson MF. A regulatory mechanism that detects premature nonsense codons in T-cell receptor transcripts in vivo is reversed by protein synthesis inhibitors in vitro. J Biol Chem 1995; 270(48): p. 28995-9003; PMID:7499432; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gardner LB. Hypoxic inhibition of nonsense-mediated RNA decay regulates gene expression and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell Biol 2008; 28(11): p. 3729-41; PMID:18362164; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.02284-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Poliseno L, Salmena L, Riccardi L, Fornari A, Song MS, Hobbs RM, Sportoletti P, Varmeh S, Egia A, Fedele G,et al. , Identification of the miR-106b∼25 microRNA cluster as a proto-oncogenic PTEN-targeting intron that cooperates with its host gene MCM7 in transformation. Sci Signal 2010; 3(117): p. ra29; PMID:20388916; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/scisignal.2000594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paulus JM, DNA metabolism and development of organelles in guinea-pig megakaryocytes: a combined ultrastructural, autoradiographic and cytophotometric study. Blood 1970; 35(3): p. 298-311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Petrocca F, Visone R, Onelli MR, Shah MH, Nicoloso MS, de Martino I, Iliopoulos D, Pilozzi E, Liu CG, Negrini M,et al. , E2F1-regulated microRNAs impair TGFbeta-dependent cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell 2008; 13(3): p. 272-86; PMID:18328430; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuchen S, Resch W, Yamane A, Kuo N, Li Z, Chakraborty T, Wei L, Laurence A, Yasuda T, Peng S,et al. , Regulation of microRNA expression and abundance during lymphopoiesis. Immunity 2010; 32(6): p. 828-39; PMID:20605486; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bell ML, Buvoli M, Leinwand LA. Uncoupling of expression of an intronic microRNA and its myosin host gene by exon skipping. Mol Cell Biol 2010; 30(8): p. 1937-45; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.01370-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mendell JT, CM ap Rhys HC. Dietz, Separable roles for rent1/hUpf1 in altered splicing and decay of nonsense transcripts. Science 2002; 298(5592): p. 419-22; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1074428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Navarro F, Gutman D, Meire E, Cáceres M, Rigoutsos I, Bentwich Z, Lieberman J. miR-34a contributes to megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells independently of p53. Blood 2009; 114(10): p. 2181-92; PMID:19584398; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2009-02-205062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chu EC, Tarnawski AS. PTEN regulatory functions in tumor suppression and cell biology. Med Sci Monit 2004; 10(10): p. RA235-41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cornejo MG, Mabialah V, Sykes SM, Khandan T, Lo Celso C, Lopez CK, Rivera-Muñoz P, Rameau P, Tothova Z, Aster JC,et al. , Crosstalk between NOTCH and AKT signaling during murine megakaryocyte lineage specification. Blood 2011; 118(5): p. 1264-73; PMID:21653327; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2011-01-328567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Toyokawa G, Masuda K, Daigo Y, Cho HS, Yoshimatsu M, Takawa M, Hayami S, Maejima K, Chino M, Field HI,et al. , Minichromosome Maintenance Protein 7 is a potential therapeutic target in human cancer and a novel prognostic marker of non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer 2011; 10: p. 65; PMID:21619671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bortoluzzi S, Bisognin A, Biasiolo M, Guglielmelli P, Biamonte F, Norfo R, Manfredini R, Vannucchi AM. Characterization and discovery of novel miRNAs and moRNAs in JAK2V617F-mutated SET2 cells. Blood 2012; 119(13): p. e120-30; PMID:22223824; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2011-07-368001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li Q, Zou C, Zou C, Han Z, Xiao H, Wei H, Wang W, Zhang L, Zhang X, Tang Q,et al. , MicroRNA-25 functions as a potential tumor suppressor in colon cancer by targeting Smad7. Cancer Lett 2013; 335(1): p. 168-74; PMID:23435373; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou Y, Hu Y, Yang M, Jat P, Li K, Lombardo Y, Xiong D, Coombes RC, Raguz S, Yagüe E. The miR-106b approximately 25 cluster promotes bypass of doxorubicin-induced senescence and increase in motility and invasion by targeting the E-cadherin transcriptional activator EP300. Cell Death Differ 2014; 21(3): p. 462-74; PMID:24270410; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cdd.2013.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Roy A, Haldar S, Basak NP, Banerjee S. Molecular cross talk between Notch1, Shh and Akt pathways during erythroid differentiation of K562 and HEL cell lines. Exp Cell Res 2013; 320(1): p. 69-78; PMID:24095799; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ishigaki Y, Li X, Serin G, Maquat LE. Evidence for a pioneer round of mRNA translation: mRNAs subject to nonsense-mediated decay in mammalian cells are bound by CBP80 and CBP20. Cell 2001; 106(5): p. 607-17; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00475-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Roy A, Basak NP, Banerjee S. Notch1 intracellular domain increases cytoplasmic EZH2 levels during early megakaryopoiesis. Cell Death Dis 2012; 3: p. e380; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cddis.2012.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.