Abstract

Aim

To see if disorders prevalent in infants born extremely preterm cluster.

Design

Observational cohort study

Setting

University-affiliated newborn intensive care nurseries

Subjects

1223 infants born before the 28th week of gestation who survived until 36 weeks when the diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) could be made.

Interventions

None

Main outcome measures

An echolucent lesion of the cerebral white matter, moderate or severe ventriculomegaly on a protocol cranial ultrasound scan, BPD, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and early and late bacteremia.

Results

After adjustment for gestational age, children who had severe NEC (Bell stage IIIb) were at increased risk of severe ROP (stage 3+), severe BPD (defined as both oxygen and ventilator dependent), and late bacteremia. Children who had early bacteremia were at increased risk of late bacteremia and severe ROP. Those who had late bacteremia were at increased risk of severe ROP, while children who had severe ROP were at increased risk of severe BPD.

Conclusions

NEC is the disorder common to most of the clusters, but we do not know if its onset occurred before the others. Organ-damage-promoting substances, however, have been found in the circulation of newborn animals with bowel inflammation, supporting the view that NEC contributes to the damage of other organs.

Keywords: preterm, white matter damage, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, retinopathy of prematurity, necrotizing enterocolitis, bacteremia, Infant, Newborn, Premature Birth, Leukomalacia, Periventricular

Introduction

Five disorders occur much more commonly among extremely low gestational age newborns (ELGANs) than among infants born close to term, cerebral white matter damage, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and bacteremia. ELGANs are believed to be at such increased risk of these disorders because of a combination of characteristics related to immaturity, exposures associated with preterm delivery, and neonatal intensive care (1–3).

Yet little is known about the co-occurrence of these disorders. Is an ELGAN who has one at increased risk of another? A recognition that some of these disorders tend to occur in the same infants would provide an impetus to seek similarities in their risk profiles. That is what we did in our sample of 1223 infants born before the 28th week of gestation who survived until 36 post-menstrual weeks when the diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) could be made.

Methods

The ELGAN study was designed to identify characteristics and exposures that increase the risk of structural and functional neurologic disorders in ELGANs (the acronym for Extremely Low Gestational Age Newborns) (4). During the years 2002–2004, women delivering before 28 weeks gestation at 14 participating institutions in 11 cities in 5 states were asked to enroll in the study. The enrollment and consent processes were approved by the individual institutional review boards.

Mothers were approached for consent either upon antenatal admission or shortly after delivery, depending on clinical circumstance and institutional preference. 1249 mothers of 1506 infants consented. Approximately 260 women were either missed or did not consent to participate. The sample for this set of analyses is limited to the 1223 ELGANs who had at least one set of protocol ultrasound scans of the head, survived to 36 weeks post-menstruation, and for whom we had information about the absence or presence of bacteremia, the stage of NEC and the stage of ROP.

Newborn variables

a. Gestational age

The gestational age estimates were based on a hierarchy of the quality of available information. Most desirable were estimates based on the dates of embryo retrieval or intrauterine insemination or fetal ultrasound before the 14th week (62%). When these were not available, reliance was placed sequentially on a fetal ultrasound at 14 or more weeks (29%), LMP without fetal ultrasound (7%), and gestational age recorded in the log of the neonatal intensive care unit (1%).

b. Bacteremia

Documented early bacteremia was defined as recovery of an organism from blood drawn during first week, and late bacteremia as recovery of an organism from blood drawn during weeks 2, 3 or 4. Specific organisms were not identified. The bacteremia was classified as presumed if the culture was negative and the clinician treated the baby with antibiotics for more than 72 hours.

c. Cranial ultrasound scans

Routine scans always included the six standard quasi-coronal views and five sagittal views using the anterior fontanel as the sonographic window (5). All 1223 infants in this sample had had at least one set of protocol ultrasound scans and 844 had all three sets. The three sets of protocol scans were defined by the postnatal day on which they were obtained. Protocol 1 scans were obtained between the first and fourth day (N=924); protocol 2 scans were obtained between the fifth and fourteenth day (N=1143), and protocol 3 scans were obtained between the fifteenth day and the 40th week (N=1200).

All ultrasound scans were read by two independent readers who were not provided clinical information. Each set of scans was first read by one study sonologist at the institution of the infant’s birth, and then by a sonologist at another ELGAN study institution. When the two readers differed in their recognition of moderate/severe ventriculomegaly (VM), or an echolucent (hypoechoic) lesion (EL), the films were sent to a third (tie-breaking) reader who did not know what the readers reported.

d. Retinal examinations

Participating ophthalmologists helped prepare a manual and data collection form, and then participated in efforts to minimize observer variability. Definitions of terms were those accepted by the International Committee for Classification of ROP.[(6)] In keeping with guidelines, the first ophthalmologic examination was within the 31st to 33rd post-menstrual week (7). Follow-up exams were as clinically indicated until normal vascularization began in zone lll.

e. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD)

BPD was defined by receipt of oxygen therapy at 36 weeks adjusted gestation. If the infant also required ventilation assistance, the BPD was classified as severe.

f. Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)

NEC was classified according to the modified Bell staging system (8). Stage IIIb (advanced surgical NEC) was diagnosed if the infant required an exploratory laparotomy or placement of a Penrose drain due to either a gastrointestinal perforation or progressive clinical deterioration without perforation. Isolated intestinal perforation was not considered NEC.

Data analysis

The generalized form of the main null hypothesis evaluated is that the occurrence of each neonatal disorder is independent of the occurrence of every other neonatal disorder. We also evaluated two sub-hypotheses. The first is a limitation of the main hypothesis to severe forms of each disorder. The second is that the clustering of disorders or severe forms of these disorders does not vary with gestational age.

We considered an association between 2 disorders to be of interest if the observed number of cases (O) was at least 50% more common than expected (E) based on the assumption that the 2 disorders occur independently of each other (O/E =1.5) (Tables 1–4). We created logistic regression models of a severe disorder as a function of another severe disorder, adjusting only for gestational age (23–24, 25–26, 27 weeks). Statistically significant odds ratios had a lower bound 95% confidence interval that was greater than 1.0, and are identified in Table 5 by bold typeface.

Table 1.

The distribution of the two ultrasound lesions among children with and without each of the disorders listed on the left. These are row percents.

| Ultrasound lesion | Row | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal disorder | Ventriculomegaly | Echolucent lesion | N | |

| Column N | 122 | 85 | 1223 | |

| Row percent | 10 | 7 | ||

| NEC | None-Stage IIIa | 9 | 7 | 1136 |

| Stage IIIb | 22 | 12 | 49 | |

| Isolated perf | 11 | 5 | 38 | |

| ROP | None | 9 | 6 | 316 |

| Stage 1/2 | 9 | 7 | 546 | |

| Stage 3/4/5 | 12 | 8 | 361 | |

| BPD severity | No BPD | 9 | 6 | 583 |

| O2 only | 11 | 8 | 517 | |

| O2 + vent | 11 | 7 | 123 | |

| Early bacteremia | No | 9 | 6 | 704 |

| Presumed | 11 | 7 | 439 | |

| Documented | 11 | 10 | 79 | |

| Late bacteremia | No | 10 | 7 | 722 |

| Presumed | 10 | 2 | 185 | |

| Documented | 11 | 10 | 313 | |

Table 4.

The frequency of each form of BPD among children who had each form of bacteremia. These are row percents.

| Neonatal disorder | BPD severity | Row | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2 + vent | O2 only | No BPD | N | ||

| Column N | 123 | 517 | 583 | 1223 | |

| Row percent | 10 | 42 | 48 | ||

| Early bacteremia | No | 10 | 39 | 50 | 704 |

| Presumed | 11 | 45 | 44 | 439 | |

| Documented | 6 | 51 | 43 | 79 | |

| Late bacteremia | No | 8 | 39 | 52 | 722 |

| Presumed | 11 | 51 | 38 | 185 | |

| Documented | 13 | 45 | 41 | 313 | |

Table 5.

The ratio of observed/expected occurrences of two disorders together. Only the most severe forms of BPD, NEC, and ROP are considered here. The numbers appear below the dark blue boxes on the diagonal. The ratios are above these boxes on the diagonal. Bolded ratios are statistically significantly different from 1.

|

BOWEL NECa |

BRAIN VM/EL |

RETINA ROPb |

LUNG BPDc |

BLOOD (Bacteremia) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earlyd | Lated | |||||

| BOWEL | 2.0 | 2.1 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 1.3 | |

| BRAIN | 14/6.9 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | |

| RETINA | 30/14.5 | 61/50.8 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.3 | |

| LUNG | 18/6 | 19/17 | 62/34 | 0.6 | 1.3 | |

| BLOOD early | 3/3.2 | 14/11.1 | 35/23.3 | 5/8.0 | 1.6 | |

| BLOOD late | 17/12.6 | 52/44.1 | 118/92.6 | 42.31.6 | 33/20.3 | |

Bell stage IIIb

Stage 3, 4, or 5

Oxygen and ventilator dependent

Documented bacteremia only

We evaluated 3-item clusters in two ways. The first assumed that every item occurred independently of every other item. The second way assumed only that the third item occurred independently of the two-item cluster.

Results

Of the 1223 infants in this sample, 21% were born before the 25th week, 47% were born during the 25th and 26th weeks, and 33% were born in the 27th week (Supplement Table A, bottom row). Each of the six disorders evaluated occurred more commonly than the expected 21% among those born at the lowest gestational ages. The proportion of children in the middle gestational age group who had the disorder or the severe form of the disorder closely approximated the expected 47%. Consequently, the distribution among the ELGANs born during the 27th week is fairly much a reversal of what is seen among those born before the 25th week.

ELGANs who developed Bell stage IIIb NEC had an incidence of each ultrasound lesion that appreciably exceeds the incidence among children who either had no NEC, NEC that did not require surgery or an isolated perforation (Table 1). In contrast, the incidence of each ultrasound lesion did not increase with increasing severity of ROP. The 24 infants who developed stage 4/5 ROP, however, had an increased incidence of ventriculomegaly. Children who developed BPD had a distribution of each ultrasound lesion that differed minimally from that of children who did not develop BPD. Infants who had documented bacteremia, whether or early or late, were at a minimally elevated risk of an echolucent lesion.

Only 4% of all ELGANs required surgery for NEC (stage IIIb) and 3% developed an isolated perforation of the bowel (Table 2). The incidence of these two disorders is minimally increased among children who developed BPD, but did not require ventilation assistance. Infants who were both oxygen and ventilator dependent at 36 weeks post-menstrual age, however, had an incidence of stage IIIb NEC that was five times higher than that of infants who did not develop BPD (15% vs 3%). The incidence of both stage IIIb NEC and isolated perforation of the bowel increased with increased severity of ROP. Infants with early and late documented bacteremia were at increased risk of isolated intestinal perforation. Only infants who developed late bacteremia, however, were more likely than their peers without any suspicion or documentation of late bacteremia to have surgery for NEC (5% vs 3%).

Table 2.

The frequency of each form of necrotizing enterocolitis among children with and without each of the disorders listed on the left. These are row percents.

| Neonatal disorder | Necrotizing enterocolitis | Row | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None-Stage IIIa | Stage IIIb | Isolated perf | N | ||

| Column N | 1123 | 62 | 38 | 1223 | |

| Row percent | 93 | 4 | 3 | ||

| ROP | None | 97 | 2 | 1 | 316 |

| Stage 1/2 | 95 | 3 | 3 | 546 | |

| Stage 3/4/5 | 86 | 8 | 6 | 361 | |

| BPD severity | No BPD | 96 | 3 | 2 | 583 |

| O2 only | 91 | 5 | 4 | 517 | |

| O2 + vent | 80 | 15 | 5 | 123 | |

| Early bacteremia | No | 94 | 4 | 2 | 704 |

| Presumed | 92 | 4 | 4 | 439 | |

| Documented | 89 | 4 | 8 | 79 | |

| Late bacteremia | No | 96 | 3 | 1 | 722 |

| Presumed | 88 | 6 | 5 | 185 | |

| Documented | 89 | 5 | 6 | 313 | |

The incidence of stage 3 or higher ROP was 15% among children who did not develop BPD, 41% among those who were oxygen dependent but not ventilator dependent, and fully 53% among children who were both oxygen and ventilator dependent (Table 3). Infants who had presumed or documented bacteremia, whether early or late, were at increased risk of Stage 3 or higher ROP.

Table 3.

The frequency of each form of retinopathy of prematurity among children who were and were not oxygen dependent at 36 weeks post-menstrual age. These are row percents.

| Neonatal disorder | Retinopathy of prematurity stage | Row | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1/2 | 3/4/5 | N | ||

| Column N | 316 | 546 | 361 | 1223 | |

| Row percent | 26 | 45 | 30 | ||

| BPD severity | No BPD | 38 | 47 | 15 | 583 |

| O2 only | 15 | 44 | 41 | 517 | |

| O2 + vent | 11 | 37 | 53 | 123 | |

| Early bacteremia | No | 30 | 44 | 26 | 704 |

| Presumed | 20 | 47 | 33 | 439 | |

| Documented | 20 | 35 | 44 | 79 | |

| Late bacteremia | No | 30 | 48 | 23 | 722 |

| Presumed | 16 | 41 | 43 | 185 | |

| Documented | 22 | 40 | 38 | 313 | |

Children who had early bacteremia were not at increased risk of BPD (Table 4). The risk of BPD was minimally increased among those who developed late bacteremia.

After adjustment for gestational age, children who had severe NEC were at increased risk of severe ROP, severe BPD, and late bacteremia (Table 5). In addition, children who had early bacteremia were at increased risk of severe ROP, and of late bacteremia, while children who had late bacteremia were at increased risk of severe ROP, and children who had severe ROP were at increased risk of severe BPD.

Fourteen children had the three-item cluster of severe BPD, severe NEC and severe ROP, whereas the expected number is 1.4 if each occurred independently of the others (data not shown). These 14 children account for 22% of the 65 children who had the cluster of severe BPD and severe ROP, 47% of the 30 children who had the cluster of severe NEC and severe ROP, and 93% of the 15 children who had the cluster of severe BPD and severe NEC. These percents are best interpreted in light of the observation that severe NEC occurred in only 4% of children in the entire sample (49/1223) (see Table 1).

We conservatively take the position that the occurrence of a third item with a two-item cluster should be evaluated in light of the observed clustering of the first two items, and not in light of the first two items occurring independently of each other. In this approach, the expected clustering of severe NEC with the cluster of severe BPD and severe ROP is 2.6 [(65)×(0.04)], is less than the higher ratio of 5.4 (14/2.6) when total independence is assumed. In light of these observations, it seems reasonable to invoke a contribution of severe NEC to the clustering of severe BPD and severe ROP.

One explanation for the clustering of these disorders invokes a heightened vulnerability associated with immaturity. If this explanation is correct, then the clusters should be less apparent as gestational age increases. However, that is not what we see here. Two disorders occurred more frequently than expected in all of the three gestational age groups (severe NEC with white matter damage, and severe NEC with severe BPD) (Supplement Table B). An additional two clusters not seen in the least mature were seen among infants born after the 24th week of gestation (severe BPD with severe ROP, and severe NEC with severe ROP).

Discussion

We found that some of the disorders that occur preferentially in the extremely low gestational age newborn (ELGAN) tend to occur together more commonly than would be expected if they were independent. This was most evident for severe NEC and late bacteremia, which occurred more often than expected in infants who had severe BPD and severe ROP.

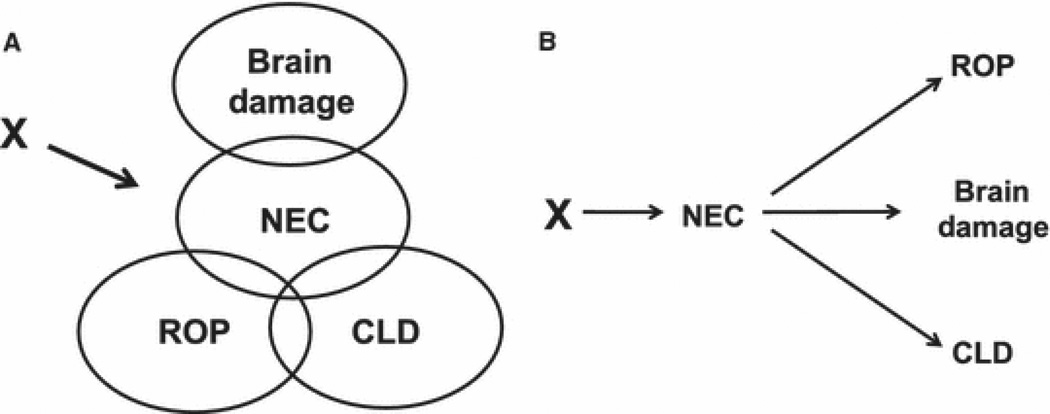

One explanation for these associations is that these disorders share endogenous antenatal characteristics (9) or common antenatal exposures (10). Figure 1a illustrates this.

Figure 1. The clustering of disorders in infants born before the 28th week of gestation.

Two models of the interrelationships among the disorders that occur preferentially among infants born at extremely low gestational ages. The first model (A) assumes that a common characteristic or exposure contributes to each of the four groups of disorders. The second model (B) assumes that NEC produces conditions that promote the occurrence of the other disorders.

Because eye (11) and lung (12) diseases in the preterm newborn appear to have antenatal antecedents, the association of severe NEC with these severe disorders appears to provide supplemental information about their progression. Perhaps an antecedent or consequence of severe NEC, such as bacteremia, influences the risk of these other disorders (Figure 1b). One variation on this theme is that physicians contributed to some of the adversities. Respiratory support for NEC might increase the risk of BPD (13, 14) and ROP (15).

Another variation is that inflammation contributes to NEC (16), which can in turn promote inflammation (17). In animal models, inflammation influences the risk of disordered lung development (12), and oxygen-induced retinopathy (18). In humans, inflammation appears to contribute to the occurrence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (19), and retinopathy of prematurity (20).

Inflammation-promoting bacteria might gain access to the circulation by a process called bacterial translocation, which can be a consequence of gut barrier dysfunction (21). In light of our finding that late bacteremia is part of the clusters that include NEC and BPD or ROP, we consider this explanation a distinct possibility.

A somewhat more attractive possibility is that some organ-damaging, circulating products of inflammation are released from the bowel even before trans-endothelial migration of bacteria occurs. Among the known circulating products of inflammation associated with NEC are endotoxin, chemokines, cytokines, and matrix metalloproteinases (17)] These have been implicated in damage to the lung (19), and retina (22).

The association among organ disorders is most evident with the severe form of NEC (stage IIIb), the severe form of BPD (ventilator dependent), and the most severe forms of ROP (stages 3, 4, and 5). This might be a consequence of the sum of adverse exposures (one more broke the camel’s back) (23) or sensitization (24).

Our study has several strengths, including a large number of infants selected on the basis of gestational age and not birth weight (25). All data were collected prospectively. In addition, we have minimized observer variability as best we can in the interpretation of ultrasound scans, as well as minimizing observer variability of retinal examinations (5).

The weaknesses of our study are those of all observational studies. We are unable to distinguish between causation and association as explanations for what we found. In addition, the sickest infants were more likely to be treated more aggressively than others who were not quite so sick, making our study prone to confounding by indication (26).

In conclusion, severe forms of the disorders that occur more often in ELGANs than in infants born at term tend to occur together more commonly than would be expected if they were independent. Much of the clustering tended to involve severe NEC with severe forms of other organ disorders, leading to the inference that something about severe NEC contributes to damage in other organs. The clustering of late bacteremia with these same disorders raises the possibility that bacteremia or phenomena related to it accounts for the associations of NEC with these disorders. This knowledge can serve as an additional impetus to study the ways NEC might damage the brain, lung, and retina.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a cooperative agreement with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (5U01NS040069-05) and a program project grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIH-P30-HD-18655). None of the authors has a financial interest in any commercial organization that might benefit from this research, nor do any of them stand to gain financially from this research.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of their subjects, and their subjects’ families, as well as those of their colleagues.

Appendix

The following ELGAN Study colleagues made this report possible but did not contribute to the writing of the manuscript.

Children's Hospital, Boston, MA

Kathleen Lee, Anne McGovern, Susan Ursprung

Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA

Bhavesh Shah, Karen Christianson

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA

Camilia R. Martin

Brigham & Women's Hospital, Boston, MA

Linda J. Van Marter

Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA

Robert M. Insoft, Maureen Quill

Floating Hospital for Children at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA

Cynthia Cole, John M. Fiascone, Ellen Nylen

U Mass Memorial Health Care, Worcester, MA

Francis Bednarek, Beth Powers, Mary Naples

Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Richard Ehrenkranz, Joanne Williams

Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center and Forsyth Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC

Teresa Harold, Deborah Hiatt

University Health Systems of Eastern Carolina, Greenville, NC

Sherry Moseley

North Carolina Children's Hospital, Chapel Hill, NC

Carl Bose, Gennie Bose

Helen DeVos Children's Hospital, Grand Rapids, MI

Mariel Poortenga, Dinah Sutton

Sparrow Hospital, Lansing, MI

Nicholas Olomu, Carolyn Solomon, Madeleine Lenski

Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI

Padmani Karna

University of Chicago Medical Center, Chicago, IL

Michael D. Schreiber, Grace Yoon

William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, MI

Daniel Batton, Beth Kring

References

- 1.Leviton A, Blair E, Dammann O, Allred E. The wealth of information conveyed by gestational age. J Pediatr. 2005;146:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dammann O, Leviton A, Gappa M, Dammann CE. Lung and brain damage in preterm newborns, and their association with gestational age, prematurity subgroup, infection/inflammation and long term outcome. Bjog. 2005;112(Suppl 1):4–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagberg H, Mallard C, Jacobsson B. Role of cytokines in preterm labour and brain injury. Bjog. 2005;112(Suppl 1):16–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Shea TM, Allred EN, Dammann O, Hirtz D, Kuban KC, Paneth N, et al. The ELGAN study of the brain and related disorders in extremely low gestational age newborns. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuban K, Adler I, Allred EN, Batton D, Bezinque S, Betz BW, et al. Observer variability assessing US scans of the preterm brain: the ELGAN study. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:1201–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0605-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An international classification of retinopathy of prematurity. The Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1130–1134. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030908011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 2001;108:809–811. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kliegman RM, Walsh MC. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: pathogenesis, classification, and spectrum of illness. Curr Probl Pediatr. 1987;17:213–288. doi: 10.1016/0045-9380(87)90031-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capoluongo E, Ameglio F, Zuppi C. Insulin-like growth factor-I and complications of prematurity: a focus on bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46:1061–1066. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotsch F, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Mazaki-Tovi S, Pineles BL, Erez O, et al. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;50:652–683. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31811ebef6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dammann O. Inflammation and Retinopathy of Prematurity. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:975–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramer BW, Kallapur S, Newnham J, Jobe AH. Prenatal inflammation and lung development. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes D, Jr, Feola DJ, Murphy BS, Shook LA, Ballard HO. Pathogenesis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Respiration. 2010;79:425–436. doi: 10.1159/000242497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Marter LJ. Epidemiology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen ML, Guo L, Smith LE, Dammann CE, Dammann O. High or low oxygen saturation and severe retinopathy of prematurity: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1483–e1492. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sodhi C, Richardson W, Gribar S, Hackam DJ. The development of animal models for the study of necrotizing enterocolitis. Dis Model Mech. 2008;1:94–98. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frost BL, Jilling T, Caplan MS. The importance of pro-inflammatory signaling in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:100–106. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sato T, Kusaka S, Hashida N, Saishin Y, Fujikado T, Tano Y. Comprehensive gene-expression profile in murine oxygen-induced retinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:96–103. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.142646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bose CL, Dammann CE, Laughon MM. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and inflammatory biomarkers in the premature neonate. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93:F455–F461. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.121327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dammann O, Brinkhaus MJ, Bartels DB, Dordelmann M, Dressler F, Kerk J, et al. Immaturity, perinatal inflammation, and retinopathy of prematurity: A multi-hit hypothesis. Early Hum Dev. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anand RJ, Leaphart CL, Mollen KP, Hackam DJ. The role of the intestinal barrier in the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. Shock. 2007;27:124–133. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000239774.02904.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferguson TA, Apte RS. Angiogenesis in eye disease: immunity gained or immunity lost? Semin Immunopathol. 2008;30:111–119. doi: 10.1007/s00281-008-0113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cory-Slechta DA. Studying toxicants as single chemicals: does this strategy adequately identify neurotoxic risk? Neurotoxicology. 2005;26:491–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eklind S, Mallard C, Arvidsson P, Hagberg H. Lipopolysaccharide induces both a primary and a secondary phase of sensitization in the developing rat brain. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:112–116. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000163513.03619.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold CC, Kramer MS, Hobbs CA, McLean FH, Usher RH. Very low birth weight: a problematic cohort for epidemiologic studies of very small or immature neonates. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:604–613. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker AM. Confounding by indication. Epidemiology. 1996;7:335–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]