Abstract

Intervention research is essential to help Hispanic American adolescents avoid drug use. This article describes an intervention research program aimed at preventing drug use among these youths. Grounded in salient epidemiological data, the program is informed by bicultural competence, social learning, and motivational interviewing theories. The program, called Vamos, is aimed at the risk and protective factors as well as the cultural prerogatives that demark the adolescent years of Hispanic American youths. Innovative in its approach, the program is delivered through a smartphone application (app). By interacting with engaging content presented via the app, youths can acquire the cognitive–behavioral skills necessary to avoid risky situations, urges, and pressures associated with early drug use. The intervention development process is presented in detail, and an evaluation plan to determine the program's efficacy is outlined. Lessons for practice and intervention programming are discussed.

Keywords: prevention, field of practice, addictions, field of practice, adolescents, population, Hispanics, population

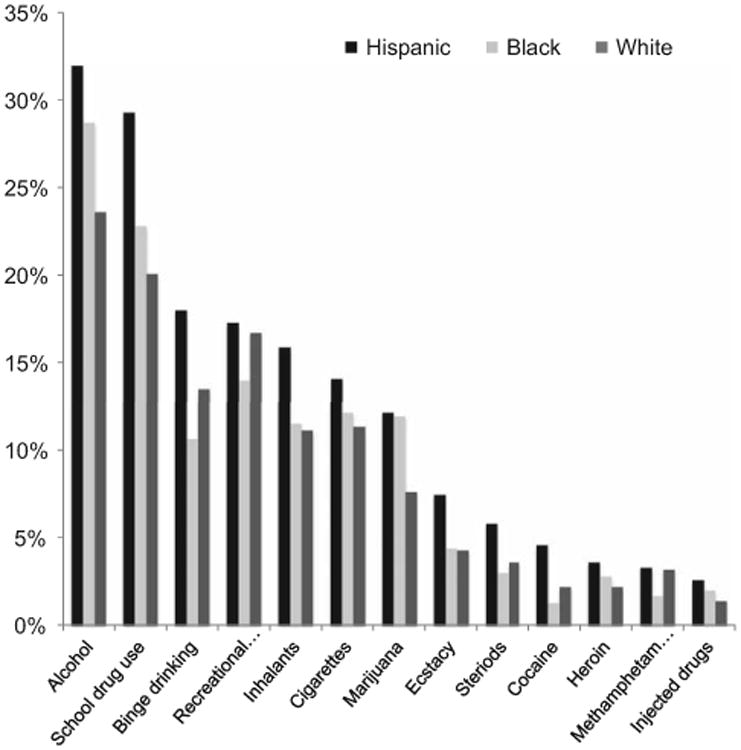

America's largest ethnic minority group, Hispanic Americans are a youthful population. One third of Hispanic Americans are under the age of 18 years (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). Unfortunately, too many Hispanic youths are at risk for problems with school, crime, violence, and lifelong underemployment (Fry, 2003; O'Donnell, O'Donnell, Wardlaw, & Stueve, 2004; Rodgers & Freeman, 2006). Related to and exacerbating these problems are drug use patterns among Hispanic adolescents. As early as ninth grade, Hispanic adolescents outpace their Black and White peers in their use of most harmful substances (Figure 1; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Drug use continues to challenge Hispanic youths throughout their later adolescent years and into adulthood (De La Rosa, Holleran, Rugh, & MacMaster, 2005). Efforts to prevent Hispanic youths from using drugs before use patterns become ingrained are needed.

Figure 1.

Drug use among ninth graders.

This article describes the creation of a drug abuse prevention program for Hispanic adolescents. In so doing, the article suggests a template for how practitioners and practice researchers can develop intervention programs for identified social problems and designated populations. The article begins by summarizing the epidemiology and theoretical foundation for drug abuse prevention among Hispanic youths. We give the rationale for an innovative intervention delivery vehicle and summarize and illustrate the resulting program. After identifying strategies for evaluating the prevention program, we discuss the relative merits and limitations of the intervention approach.

Epidemiology and Prevention Science

Explanations for drug use by Hispanic adolescents implicate pan-ethnic variables (e.g., experimentation, value of deviant behavior, peer influences, willingness to use drugs, stress and emotional distress, body image, parental monitoring, media influences, availability) and ethnic-specific variables (e.g., cultural identification, conflicting values, adult modeling, misperceptions of harm, traditional gender roles, and sensation seeking; Chartier, Hesselbrock, & Hesselbrock, 2009; Félix-Ortiz & Newcomb, 1999; Parsai, Voisine, Marsiglia, Kulis, & Nieri, 2009; Strait, 1999).

Acculturation is oft-cited to explain drug use by young Hispanics. Whereas some data suggest that stress arises from pressures to acculturate, other findings show that more acculturated youths are at greater risk (Gfroerer & De la Rosa, 1993). The relationship between acculturation and drug use may be curvilinear: too much or too little acculturation may heighten risks of drug use more than a bicultural perspective (Guilamo-Ramos, Jaccard, Johansson, & Turrisi, 2004). Youths who experience stress issuing jointly from their Hispanic culture and from the dominant surrounding culture appear inordinately at risk (Romero, Martinez, & Carvajal, 2007).

Religiosity, community connectedness, educational achievement, family supports, traditional values, and self-control have been identified as protective factors for Hispanic youths (Félix-Ortiz & Newcomb, 1999). Additionally protective are accurate social norms about drug use among youths' peers, appropriate assertiveness, coping skills, positive self-image, ability to resist media influences and to deal with conflict, and self-efficacy about drug use avoidance (Newcomb & Félix-Ortiz, 1992; Sale, Sambrano, Springer, & Turner, 2004).

Addressing risk and protective factors, various prevention approaches have sought to reduce drug use among Hispanic youths (Crunkilton, Paz, & Boyle, 2005; Gil, Wagner, & Tubman, 2004; Marsiglia, Peña, Nieri, & Nagoshi, 2010; Marsiglia, Yahiku, Kults, Nieri, & Lewin, 2010). Some approaches have been designed for Hispanic youths; others have been modified for these youths. Across prevention programs, most investigators call for culturally tailored approaches, grounded in theory, and responsive to current findings on why Hispanic adolescents use drugs (Jani, Ortiz, & Aranda, 2009; Santisteban & Mena, 2009).

Theory

Holding practical implications to inform prevention programming for Hispanic youths are theories of bicultural competence, social learning, and motivational interviewing. Bicultural competence—in the context of drug use among Hispanic adolescents—defines a youth's ability to combine the strengths of Hispanic culture with the realities of living in a dominant non-Hispanic society (LaFromboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993). The applicability of bicultural competence theory gains credence from data on relationships between acculturation and drug use among Hispanic youths and from bicultural competence research on drug abuse prevention (Castro, Sharp, Barrington, Walton, & Rawson, 1991; Schinke et al., 1988). Principles of social learning theory have long been hallmarks of successful drug abuse prevention programming with Hispanic and other American adolescents (Nation et al., 2003; Petraitis, Flay, & Miller, 1995). Social learning theory explains how people learn through observation, instruction, and rewards (Bandura, 1977). Over the years, learning theorists have favored a social–cognitive theoretical model, which predicts behavior change through mediator variables of self-efficacy, intentions, and related perceptions (Bandura, 1986, 1997). Motivational interviewing, characterized by reflective listening methods through which people hear themselves articulating their motivations for change, is heavily employed in programs aimed at drug and other substance use (Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005; Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The theory has been used successfully with Hispanic samples and, with proper adaptation, holds promise for approaches to prevent drug use among Hispanic youths (Añez, Silva, Paris, & Bedregal, 2008).

Intervention Delivery

Prevention program delivery, not unlike the delivery of any intervention program, has long relied on manualized approaches that reach end users through direct, face-to-face contact. For drug abuse prevention approaches, this has led to programs sited in schools, youth centers, and other settings where large numbers of youths congregate. Programs physically sited within youth-centered institutions, however, bring logistic challenges. These include securing the necessary space, training and monitoring program delivery staff, and competing with core mission activities of the host institution (e.g., classroom teaching, after-school programs, team sports).

Prevention programs delivered by computers offer an alternative. Computer-based programs can be delivered outside of schools and other institutional venues and are not dependent on outside resources for their delivery. Consequently, these programs can reach youths who would not otherwise participate in drug abuse prevention efforts. For Hispanic adolescents, personal computing increasingly involves small, portable devices including smartphones, tablets, and laptops (Pew Internet and American Life Project, 2009). Hispanic youths are inordinately Internet savvy. More than their White counterparts, 8- to 18- year- old Hispanics are more likely to access online social networking sites, videos, text messaging, and e-mail (Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010). Moreover, minority and other under-served youths are rapidly choosing smartphones to access the Internet (Pew Social Trends Staff, 2010). Indicative of the growing popularly of smartphones, increasing numbers of adolescents use them to complete school homework—with Hispanic students doing so at higher rates than African American or White students (Reaney, 2012).

Albeit computerized drug abuse prevention programs have not been widely tested with Hispanic adolescents, and smartphone delivered programs are in their nascency, programs for general populations of adolescents and delivered by various computer platforms have been found efficacious (Bauer & Moessner, 2013; Marsch, Bickel, & Grabinski, 2007; Peng, Crouse, & Lin, 2013; Schinke, Cole, & Fang, 2009). Accordingly, the exploration of mobile computing technology— mobile smartphones especially—has considerable potential for delivering drug abuse prevention programs to Hispanic youths. Smartphone applications (apps) are dedicated to a specific set of functions, have simple menus, and quickly become familiar to users. Salient for implementing interventions under real-world circumstances, apps let youths access drug abuse prevention content whenever they need it.

Once tested, prevention programming delivered by smartphone app lends itself to immediate and inexpensive dissemination. No training of intervention agents is necessary. Hispanic youths throughout the United States can directly access the app. Youths are familiar and comfortable with this mobile computer delivery mode. It is the same technology through which they e-mail and text message their friends, play games, and access the Internet.

Vamos Prevention Program

We are testing the viability of a smartphone-delivered drug abuse prevention program for Hispanic adolescents. Informed by bicultural competence, social learning, and motivational interviewing theories, the program—called Vamos—consists of 10 integrated sessions. Program sessions are organized by themes and cognate targeted skills (Table 1). Employing linked scenarios that let youths practice and acquire the skills, Vamos sessions include stimulus questions that require responses before youths can progress in the program. Youths interact with each Vamos session on their smartphones for roughly 15 minutes. In each session, youths watch and respond to a series of vignettes involving a protagonist, whose interactions the youths control, and an antagonist who presents situations that require action from the protagonist. Vamos protagonists match the gender of youths who interact with the program. The app is compatible with iOS and Android platforms, which together account for over 90% of smartphone operating systems.

Table 1.

Vamos Session Content: Male Version.

| Theme | ||

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Skills | Situations Encountered | Illustrative Stimulus Questions |

| Cheating | ||

| Problem solving | Jennifer wants to copy Mateo's homework. |

|

| Refusal responses | ||

| Bullying | ||

| Problem solving | A classmate is tripped, left out of a basketball game, and poked fun at. |

|

| Assertiveness | ||

| Culture | ||

| Cultural sensitivity | Mateo translates for his father, tires of family foods, and is addressed in Spanish by a waiter. |

|

| Decision making | ||

| Goals | ||

| Goal setting | Mateo chooses a goal, strives to achieve it, and faces challenges. |

|

| Social norms | ||

| Assertiveness | Mateo sees how peers shape his decisions. |

|

| Media literacy | ||

| Peer pressure | ||

| Refusal responses | Friends want Mateo to drink, share private information online, and lend them money. |

|

| Assertiveness | ||

| Emotions | ||

| Emotional regulation | Mateo becomes angry, sad, and frustrated. |

|

| Anger management | ||

| Gender | ||

| Media literacy | Friends and family want Mateo to be strong, not show pain, and not feel upset. |

|

| Reducing gender biases | ||

| Healthy living | ||

| Problem solving | Mateo makes choices about food, sleep, and exercise. |

|

| Responsibility | ||

| Decision making | Mateo has new freedoms. |

|

Each Vamos session presents youths with a problem situation and a series of decision steps necessary to resolve the problem. Learning theory is incorporated into Vamos through principles of modeling, behavioral rehearsal, reinforcement, and corrective feedback. Bicultural competency is incorporated through lessons aimed at celebrating Hispanic cultural values and life skills to help youths reach their full potential within the dominant majority culture. Motivational interviewing principles guide the way youths are prompted to resolve problem situations.

Aimed to build youths' cognitive problem-solving and behavioral decision-implementation skills, Vamos presents youths with a series of interactions in which they can try out their learned skills. Besides situations involving drug use, these span commonplace situations youths encounter at school, home, and with their friends. Vamos communicates its content through interactions among the program's cartoon characters. A screenshot of an illustrative interaction is shown in Figure 2. In this scene, Jennifer, the protagonist in Vamos's female version, is walking to school with her classmate, Mateo, the antagonist in the female version. In the male version, Mateo is the protagonist and Jennifer the antagonist. The situation about to unfold in Figure 2 will present Jennifer with a dilemma: Mateo forgot to do his math homework and wants to copy Jennifer's.

Figure 2.

Screen shot of Vamos prevention program.

Latina youths interacting with the female version of the program assume Jennifer's role to choose among options to resolve Jennifer's dilemma. Accessed by touch screens on their smartphones, youths experience the consequences of the option they select for Jennifer. Youths consider those consequences and, if they wish, replay the original scene, selecting different resolution options. Through this process, youths can choose the preferred option for resolving the dilemma. Because Vamos will engage Hispanic adolescents throughout the United States, the youth jargon employed, together with the scenery and situational contexts, are designed with pan-Hispanic appeal.

Youths complete one session of the Vamos app each week, provided that they have finished the prior week's session. Reminders programmed into the app, as well as e-mails and telephone calls from Vamos staff, encourage youths to complete sessions in a timely manner. Youths are further encouraged by receiving badges and other milestone rewards for moving through program sessions. Flash cards at the end of each session let youths practice what they have learned and serve as added prompts for youths to generalize their learning. Intervention delivery fidelity as youths complete the program is assessed in real time on the Vamos project server.

Evaluation

Evidence-based intervention programs for social work practice must undergo rigorous testing. For Vamos, this testing will involve a longitudinal randomized clinical trial with a nationally representative sample of Hispanic adolescents, aged 12 to 15 years. Recruited through online social networking sites, youths must assent and obtain parental permission prior to study enrollment. Once this happens, youths complete an online battery of outcome measures focused on drug use as well as measures of mediator variables associated with drug use. Moderator variable data on youths' acculturation, ethnic identity, and sociodemographic background are also gathered.

Youths are randomly divided into intervention and control arms. Intervention-arm youths interact with the 10 Vamos program sessions on their smartphones. Control-arm youths receive no intervention. Annually, all youths complete follow-up measures similar to those administered at baseline. Youths in the intervention arm additionally receive annual booster sessions consisting of developmentally indexed scenarios via the same interactive procedures employed to deliver the initial Vamos program. Comparing youths in the two study arms on past-month drug use at 3-year follow-up will form the basis for determining whether Vamos worked.

If the program is effective in reducing intervention-arm youths' drug use, it will be disseminated as widely as possible through relevant websites, media releases, and registrations with professional clearinghouses of effective intervention programs (e.g., The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices, nrepp.samhsa.gov; Cochrane Collaboration, cochrane.org; Campbell Collaboration, campbellcollaboration.org).

Discussion

Intervention research has entered an auspicious period in social work and throughout the behavioral and social sciences. Differing from descriptive, correlational, and etiological studies, intervention research can yield proven strategies for ameliorating human problems. Expectedly, however, this laudable objective is not easily accomplished. The intervention research process is complex. It requires multiple steps, usually takes years to accomplish, and does not infrequently produce equivocal or clinically insignificant results. Illustrating the initial stages of intervention research, this article considers the problem of drug use among Hispanic American youths.

Rates of and problems associated with drug use among Hispanic youths cry out for intervention efforts, particularly for responsive prevention programs. Helping youths avoid problems before they become serious is not only good practice and policy, but also cost-effective and, most of all, humane. Designing responsive prevention programs—not unlike the design of any intervention program—can profitably begin with an understanding of the epidemiology of the problem. Until we understand a problem, we lack the wherewithal to prevent it or to successfully intervene to change it. Possessing an empirical understanding, we can seek theoretical guidance. Correctly applied, theory is eminently practical. For example, because we know from learning theory that youths acquire new skills in part by watching their peers (i.e., the principle of modeling), we can build a program in which youths see others engaging in the desirable behavior.

Demanding extraordinary creativity, the delivery means for programs is part of the intervention development process. For our program and target population, the delivery means responds to institutional constraints on hosting outside intervention programs. As important, the delivery means for Vamos conforms to how today's adolescents access and apply new information. These realities suggest the potential of a computer-delivered intervention. That smartphones are fast becoming the computer of choice for American adolescents underscores the wisdom of these mobile devices for delivering prevention program content to youths.

Admittedly, not all Hispanic youths own smartphones. An intervention program app that relies on smartphones cannot, at the present time, serve the needs of all Hispanic adolescents in America. But most intervention programs, prevention programs especially, must be designed to address problems that have yet to be experienced by future youth cohorts. Thus, program delivery must anticipate a consumer market some years hence and be positioned to serve that market when its capacities align with programmatic requirements. For Vamos, our time horizon is 3 years away—when the final follow-up data from the evaluation trial will be available. Ideally, the program can then serve smartphone-equipped Hispanic youths for at least the next 5 years, or until its content is sufficiently dated to warrant refreshing.

Social work practitioners and other direct service professionals can profit from this case study on intervention development. Foremost is the need to consider from the outset the intervention program's end users. Too often, intervention research errs on the side of scientific rigor at the expense of practical application. If, for example, a prevention program is overly pedantic, complex, or simply sounds too much like school, adolescents may hesitate to engage with it. Program sessions that are excessive in length or too frequent in number may also be met unenthusiastically. Intervention sessions that are short, entertaining, and immediately applicable to a range of everyday situations are more likely to be embraced, remembered, and used. These are the reasons behind our creating roughly 15-min Vamos program sessions in animated cartoon format and using characters with which youths can readily identify.

Regardless of how promising, Vamos cannot be deemed efficacious until it is tested. The program must be subjected to research that yields causal statements about whether it reduces drug use. Only then can the program qualify as evidence based.

Hispanic Americans are a heterogeneous population. Differences among Hispanic groups—whether defined by nativity, country of origin, U.S. geographic locale, education, income, or a host of other factors—may be as great as differences between Hispanic Americans and members of other ethnic–racial groups. Owing to variations among Hispanic youths in America, the Vamos program is inherently pan-Hispanic. As a result, the prevention program is unlikely to affect all Hispanic adolescents in the same way. Trying to address the cultural prerogatives of multiple groups, the program could fail to gain traction with any one group. Evaluation data from a test of Vamos will shed empirical light on this potential limitation.

The science of drug abuse prevention and the means for delivering prevention programs are continually evolving. Invariably, programmatic evolution will bear witness to improved and more effective interventions. Theories fall in and out of favor. Programmatic content becomes dated, particularly when programs seek to capture the attention of adolescents. Technology that is relevant today will be less so tomorrow.

Intervention research is an exciting area, regardless of where professionals are involved in the process of developing, testing, and disseminating programs. It is a field where dedicated professionals can make and see a difference in solving intractable human problems. In short, the investment in building and testing an intervention is large, and so are the payoffs. Done right, intervention research can further close the artificial separation of science and practice. In so doing, it can inform clinical work, social programs, and policy. Best of all, intervention research can improve the lives of its end-user clients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, grant number R01DA031477.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Añez LM, Silva MA, Paris M, Bedregal LE. Engaging Latinos through the integration of cultural values and motivational interviewing principles. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:153–159. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. New York, NY: General Learning Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer S, Moessner M. Harnessing thevevention of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;46:508–515. doi: 10.1002/eat.22109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Sharp EV, Barrington EH, Walton M, Rawson RA. Drug abuse and identity in Mexican Americans: Theoretical and empirical considerations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1991;13:209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1991-2011 high school youth risk behavior survey data. 2013 Retrieved from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline.

- Chartier KG, Hesselbrock MN, Hesselbrock VM. Ethnicity and adolescent pathways to alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:337–345. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunkilton D, Paz JJ, Boyle DP. Culturally competent intervention with families of Latino youth at risk for drug abuse. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5:113–131. [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa M, Holleran LK, Rugh D, MacMaster SA. Substance abuse among U.S. Latinos: A review of the literature. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Félix-Ortiz M, Newcomb MD. Vulnerability for drug use among Latino adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Fry R. Hispanic youth dropping out of US Schools: Measuring the challenge. 2003 Retrieved from http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/19.pdf.

- Gfroerer J, De la Rosa M. Protective and risk factors associated with drug use among Hispanic youth. Journal Addictive Diseases. 1993;12:87–107. doi: 10.1300/J069v12n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Tubman JG. Culturally sensitive substance abuse intervention for Hispanic and African American adolescents: Empirical examples from the Alcohol Treatment Targeting Adolescents in Need (ATTAIN) project. Addiction. 2004;99:140–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Johansson M, Turrisi R. Binge drinking among Latino youth: Role of acculturation-related variables. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:135–142. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jani JS, Ortiz L, Aranda MP. Latino outcome studies in social work: A review of the literature. Research in Social Work. 2009;19:179–194. [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise T, Coleman HLK, Gerton J. Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:395–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Bickel WK, Grabinski MJ. Application of interactive, computer technology to adolescent substance abuse prevention and treatment. Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews. 2007;18:342–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Peña V, Nieri T, Nagoshi JL. Real groups: The design and immediate effects of a prevention intervention for Latino children. Social Work with Groups. 2010;33:103–121. doi: 10.1080/01609510903366202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Yahiku ST, Kults S, Nieri T, Lewin B. Influences of school Latino composition and linguistic acculturation on prevention program for youths. Social Work Research. 2010;34:6–19. doi: 10.1093/swr/34.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nation M, Crusto C, Wandersman A, Kumpfer KL, Seybolt D, Morrisey-Kane E, Davino K. What works in prevention. American Psychologist. 2003;58:449–457. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Félix-Ortiz M. Multiple protective and risk factors for drug use and abuse: Cross-sectional and prospective findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:280–296. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell L, O'Donnell C, Wardlaw DM, Stueve A. Risk and resiliency factors influencing suicidality among urban African American and Latino youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33:1–2. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014317.20704.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai M, Voisine S, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Nieri T. The protective and risk effects of parents and peers on substance use, attitudes, and behaviors of Mexican and Mexican American female and male adolescents. Youth and Society. 2009;40:353–376. doi: 10.1177/0044118X08318117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng W, Crouse JC, Lin J. Using active video games for physical activity promotion: A systematic review of the current state of research. Health Education & Behavior. 2013;40:171–192. doi: 10.1177/1090198112444956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance abuse: Organizing pieces of the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Internet and American Life Project. Latinos online: 2006-2008. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Commentary/2009/December/Latinos-Online-20062008.aspx.

- Pew Social Trends Staff. Millennials: Confident. Connected. Open to change. 2010 Retrieved from: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/02/24/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change/

- Reaney P. Young teens in U.S. use mobile devices for homework. 2012 Reuters U.S. Edition. Retrieve from: http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/11/28/us-technology-tweens-mobiles-homework-idUSBRE8AR1DC20121128.

- Rideout VJ, Foehr UG, Roberts DF. Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8- to 18-year-olds. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf.

- Rodgers WM, III, Freeman RB. How have Hispanics fared in the “Jobless Recovery”? 2006 Retrieved from http://www.americanprogress.org/kf/hispanic_labor_execsumm.pdf.

- Romero AJ, Martinez D, Carvajal S. Bicultural stress and adolescent risk behaviors in a community sample of Latinos and Non-Latino European Americans. Ethnicity & Health. 2007;12:443–463. doi: 10.1080/13557850701616854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sale E, Sambrano S, Springer JF, Turner CW. Risk, protection, and substance use in adolescents: A multi-site model. Journal of Drug Education. 2004;33:91–105. doi: 10.2190/LFJ0-ER64-1FVY-PA7L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Mena MP. Culturally informed and flexible family-based treatment for adolescents: A tailored and integrative treatment for Hispanic youth. Family Process. 2009;48:253–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Cole KC, Fang L. Gender specific intervention to reduce underage drinking among early adolescent girls: A test of a computer-mediated, mother-daughter program. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:70–77. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Orlandi MA, Botvin GJ, Gilchrist LD, Trimble JE, Locklear VS. Preventing substance abuse among American-Indian adolescents: A bicultural competence skills approach. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1988;35:87–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strait SC. Drug use among hispanic youth: Examining common and unique contributing factors. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1999;21:89–103. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Hispanic population surpasses 45 million; Now 15 percent of total. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/011910.html.