Abstract

CCA-adding enzymes are highly specific RNA polymerases that synthesize and maintain the sequence CCA at the tRNA 3′-end. This nucleotide triplet is a prerequisite for tRNAs to be aminoacylated and to participate in protein biosynthesis. During CCA-addition, a set of highly conserved motifs in the catalytic core of these enzymes is responsible for accurate sequential nucleotide incorporation. In the nucleotide binding pocket, three amino acid residues form Watson-Crick-like base pairs to the incoming CTP and ATP. A reorientation of these templating amino acids switches the enzyme's specificity from CTP to ATP recognition. However, the mechanism underlying this essential structural rearrangement is not understood. Here, we show that motif C, whose actual function has not been identified yet, contributes to the switch in nucleotide specificity during polymerization. Biochemical characterization as well as EPR spectroscopy measurements of the human enzyme reveal that mutating the highly conserved amino acid position D139 in this motif interferes with AMP incorporation and affects interdomain movements in the enzyme. We propose a model of action, where motif C forms a flexible spring element modulating the relative orientation of the enzyme's head and body domains to accommodate the growing 3′-end of the tRNA. Furthermore, these conformational transitions initiate the rearranging of the templating amino acids to switch the specificity of the nucleotide binding pocket from CTP to ATP during CCA-synthesis.

Keywords: CCA-adding enzyme, CCA-addition, DEER, EPR spectroscopy, tRNA nucleotidyltransferase, tRNA, tRNA maturation

Introduction

In every domain of life tRNAs carry the conserved nucleotide sequence CCA at their 3′-end, representing the position for amino acid attachment.1,2 In the majority of tRNA genes, this CCA-end is not encoded and has to be added post-transcriptionally by ATP(CTP):tRNA nucleotidyltransferase (CCA-adding enzyme). According to a signature element in the catalytic core, these enzymes represent members of the polymerase β family.3 Additional sequence motifs allow a further distinction of CCA-adding enzymes into class I, consisting of archaeal tRNA nucleotidyltransferases, and class II enzymes that are represented by bacterial and eukaryotic activities.4-6

For class I enzymes, detailed structures in complex with various tRNA substrates revealed that these enzymes perform a series of highly coordinated structural rearrangements during CCA-addition (reviewed in ref.7). On the other hand, much less information is available for class II CCA-adding enzymes, as only apo structures in complex with CTP and ATP have been resolved yet.8,9 Structures co-crystallized with tRNA are only available for enzymes with partial activities (CC- and A-adding enzymes), where a switch in nucleotide specificity is not observed. Yet, there are indications that also in these enzymes extensive rearrangements during nucleotide addition occur, as co-crystals consisting of an A-adding enzyme and tRNA ending with CC immediately dissolved when soaked with ATP.10 In addition, single turnover kinetics of a class II CCA-adding enzyme in the presence of glycerol revealed a strong effect on A-addition, while C-addition remained nearly unaffected. This effect was attributed to an increase of solvent viscosity by increasing the concentration of glycerol, suggesting that the enzyme conformational transition is more dominant for the A-addition.11 These data indicate that distinct structural rearrangements during nucleotide addition take also place in class II CCA-adding enzymes.

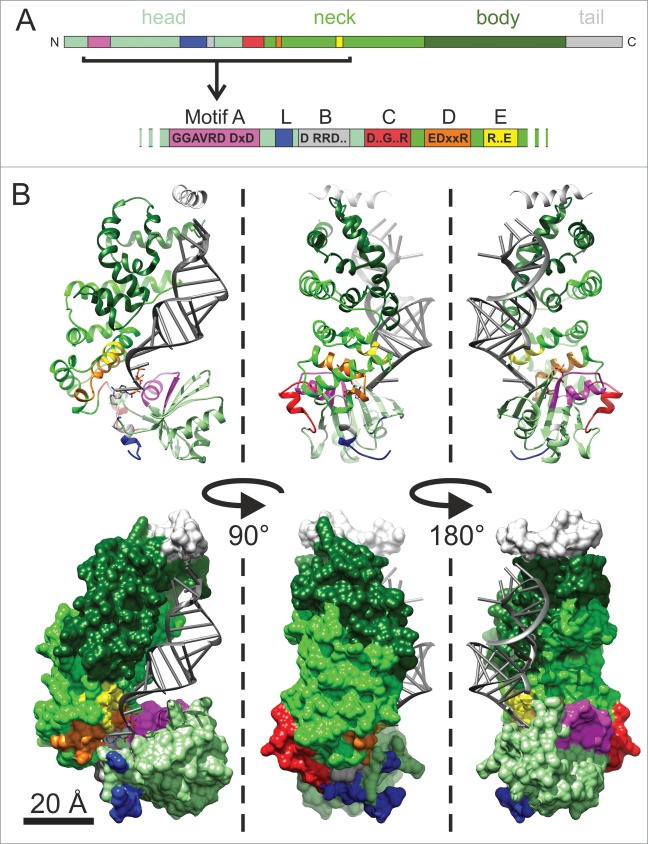

The N-terminally located catalytic core of class II enzymes consists of a set of conserved motifs playing a central role in the highly regulated addition of the CCA triplet (Fig. 1A).8,12 Motif A (representing the common signature motif of nucleotidyltransferases) is involved in the coordination of two magnesium ions required for catalysis according to the general mechanism of polymerization.13,14 It contains the conserved sequence GGxVRD (x is any amino acid) and the DxD carboxylate signature that binds the metal ions. The complete transferase signature is located in an equally conserved five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet with two flanking α-helices.8,15 Motifs B and D are essential parts of the nucleotide binding site, where motif B is involved in the discrimination against deoxy-nucleotides. Motif D, which contains a highly conserved amino acid signature (EDxxR), selectively binds CTP and ATP via the formation of specific hydrogen bonds, discriminating against UTP and GTP. Hence, this motif represents an amino-acid based template for nucleotide selection.8 The function of motifs C and E, however, is less clear, and these elements were originally described as connecting (C) or stabilizing (E) head and neck domains of the enzyme.8

Figure 1.

Conserved motifs in the N-terminally located catalytic core of class II tRNA nucleotidyltransferases. (A) The upper bar diagram shows the consensus sequences of motifs A to E in a linear scale model. The individual domains are indicated. The lower part represents an N-terminal zoom-in of the catalytic motifs. The flexible loop element (L) located between motifs A and B is indicated in blue. (B) In the co-crystal structure of a bacterial class II tRNA nucleotidyltransferase (top row: ribbon model, bottom row: surface representation) with a bound tRNA primer (grey) and an ATP analogue (see ref.10), these motifs are color-coded corresponding to the bar presentation above. It is evident that motif C, indicated in red, has no direct contact to the bound tRNA substrate but is located on the enzyme site opposite to the tRNA binding region and the catalytic core.

A sixth functional element, although lacking a conserved signature, is represented by a highly flexible loop element located between motifs A and B. This loop seems to interact with the amino acid template of motif D, and biochemical as well as molecular modeling data support a function as a lever in order to adjust the templating amino acids for CTP or ATP specificity.16 Interestingly, this loop is missing in the above mentioned CC-adding enzymes, explaining the restricted activity of these nucleotidyltransferases.17

While the connecting motif C shows a rather low level of sequence conservation with only three predominant positions (Dx(3,4)Gx(9)R), mutations therein can cause a temperature-sensitive phenotype, indicating an important role in catalysis.18 Yet, crystal structures show that the location of this motif in the enzyme does not support any interaction with tRNA or nucleotides in the catalytic core but helps to correctly position head (with motifs A and B) and neck domains (motif D) for proper catalysis (Fig 1B).8-10,15,19 Here, we demonstrate that this motif is participating in interdomain movements required for switching the enzyme's specificity from C- to A-addition. Instead of functioning as a simple connection part, our data support a function of motif C as a spring element between head and neck domains that is necessary to accommodate the growing 3′ end of the tRNA primer during polymerization. In this element, a highly conserved aspartate residue seems to function as a helix-capping element that is required to maintain the elasticity of this spring.

Results

Single amino acid substitutions reveal a function of motif C in CCA-addition

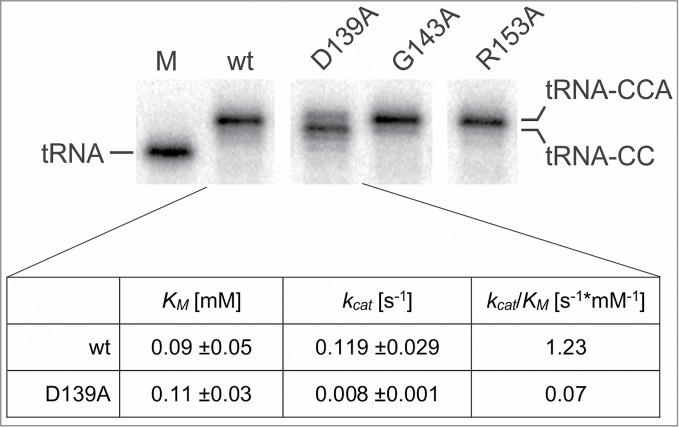

Class II nucleotidyltransferases carry a set of five specific motifs in their catalytic core (Fig. 1A).8 Whereas for most motifs a rather precise function has been identified, the more weakly conserved motif C has only been described as a connecting element for motifs B and D in the head and neck domains of the enzyme.20 Yet, due to the presence of three highly conserved residues D, G and R, it is very likely that motif C is more than just a passive bridging element in the catalytic core. To address this question, we replaced these three individual conserved positions by alanine in the human CCA-adding enzyme. The resulting enzyme variants (HsaCCA D139A, HsaCCA G143A, HsaCCA R153A) were recombinantly expressed, purified by affinity chromatography and tested for activity in the presence of all four nucleotides using a mitochondrial tRNATyr lacking the CCA-terminus as substrate. Reaction products were separated on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 2). Whereas the enzyme variants G143A and R153A catalyzed the addition of the complete CCA sequence comparable to the wt enzyme, the D139A mutant form showed a strong reduction in the addition of the terminal A position. Hence, the catalytic properties of this variant were further investigated. To rule out that the reduced A-addition represents an effect specific to the tRNATyr substrate, the determination of Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters was conducted with another substrate, yeast tRNAPhe, one of the most commonly used substrates in CCA adding reactions.16,17,21 To analyze the efficiency of the terminal A-addition. While the observed KM values of 0.09 mM and 0.11 mM did not differ significantly between the wt enzyme and the D139A variant (p = 0.8), the latter variant showed a strongly reduced kcat value of 0.008 s−1, compared to 0.119 s−1 of the wt, corresponding to a 15-fold reduction (p = 0.003; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Biochemical analysis of conserved amino acids in motif C of the human CCA-adding enzyme. The conserved amino acid positions D139, G143 and R153 were individually replaced by alanine, and the resulting enzyme variants were tested for CCA-addition using a radioactively labeled human mitochondrial tRNATyr. On the denaturing polyacrylamide gel, the G143A and R153A variants showed the addition of a complete CCA-end comparable to the wt enzyme, while variant D139A exhibits a severely reduced A incorporation. M, mock incubation of tRNATyr without enzyme. The table shows the kinetic parameters for the A-addition on tRNA-CC. While KM values do not differ significantly between wild-type enzyme (wt) and D139A variant (p = 0.8), the kcat value of the mutant enzyme form shows a 15-fold reduction compared to the wt (p = 0.003). Correspondingly, the kcat/KM values show a similar reduction for the D139A variant. The unaffected KM values indicate that both wt and D139A enzyme forms have a similar affinity for ATP, showing that this substrate is bound by the mutant enzyme with equal efficiency.

As motif C shows no direct interaction with the tRNA and nucleotide substrates, a likely function for this element is to confer a certain flexibility to the enzyme to allow an interdomain movement for switching the nucleotide specificity from C-towards A-addition, similar to the function of the flexible loop located between motifs A and B.16,17

EPR spectroscopy proves that motif C is involved in interdomain movements during catalysis

To analyze whether motif C is indeed involved in structural rearrangements of the human tRNA nucleotidyltransferase during CCA-addition, electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) experiments in combination with site-directed spin labeling (SDSL; see ref.22) were performed. This method allows the determination of distances between individual ensembles of (1-Oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methyl) methanethiosulfonate (MTSSL) spin label side chains, covalently bound to cysteine side chains at specific positions.23,24 The crystal structure of the human CCA-adding enzyme was evaluated to identify optimal spin label positions for the detection of movements between the head and the body domain (see ref.15), while minimizing the invasive effect of site-directed mutagenesis and spin labeling on enzyme function.

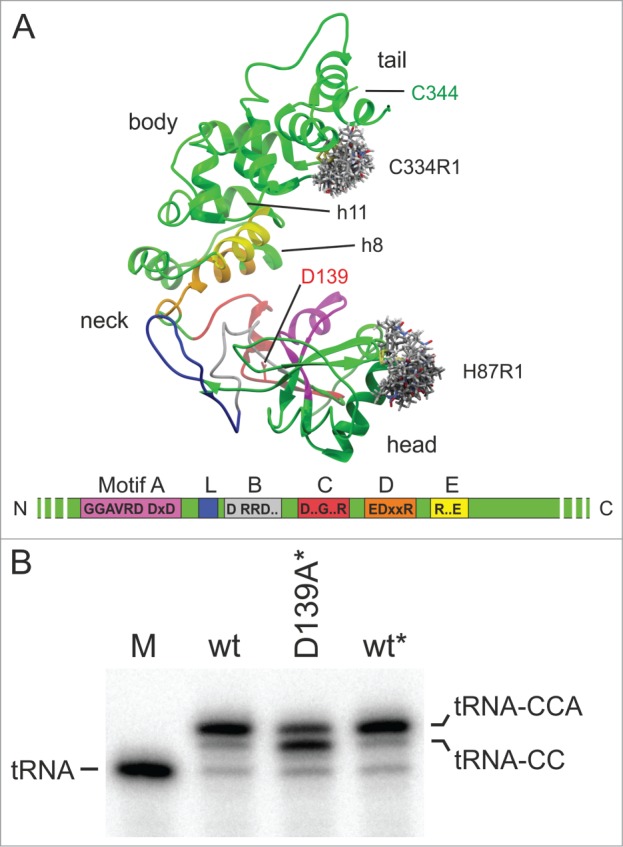

Two positions, H87 (head domain) and C334 (body domain) were identified as solvent accessible, representing possible targets for spin labeling (Fig. 3A). In preparation for SDSL, H87 had to be replaced by cysteine, introducing the mutation H87C, while C334 is one of two native cysteine residues in the human CCA-adding enzyme readily accessible to spin labeling. The second intrinsic cysteine residue at position 344 was replaced with alanine (C344A) in order to avoid the introduction of an additional spin label into the body domain. Hence, each of the resulting enzyme variants (wt and motif C mutant D139A) carried two cysteine residues with MTSSL spin label covalently bound at positions 87 (H87R1) and 334 (C334R1), respectively. The two spin-labeled enzyme variants were termed HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 and HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1, leaving the C344A mutation unmentioned in both cases. In order to rule out a possible impact of the spin label side-chains on the catalytic activity of the enzyme, both HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 and HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1, were tested for CCA-addition using a radioactively labeled tRNA substrate (Fig. 3B). Both spin labeled enzymes showed a complete or partial CCA-addition identical to that catalyzed by the corresponding unlabeled wt and D139A enzyme forms. We therefore conclude that the dual MTSSL modification did not interfere with the enzyme activity.

Figure 3.

(A) Crystal structure of the human CCA-adding enzyme with spin label rotamers at positions 87 and 334 (grey stick models calculated using MMM 2013; see ref.25). All motifs are colored according to Figure 1. Residue D139 is highlighted in stick representation (red). The second intrinsic cysteine residue located at position 344 (green) was replaced by alanine prior to spin labeling. In the neck region, α-helices h8 and h11, forming an additional spring element as described by Toh et al., are indicated.9 (B) The introduction of the spin labels has no effect on the CCA-addition to radioactively labeled human mitochondrial tRNATyr. M, mock incubation of the tRNA in the absence of enzymes. The labeled wt and D139A mutant are indicated by the asterisk. These enzyme preparations show a CCA-adding activity that is indistinguishable from that of the unlabeled versions, with a full CCA end added by the wt* enzyme and a reduced A-addition catalyzed by the D139A* variant.

To characterize the experimentally determined distance distributions resulting from the double electron-electron resonance (DEER) experiments, in silico spin labeling was performed using the substrate-free crystal structure of the human CCA-adding enzyme (PDB: 1OU5) and the rotamer library approach (RLA) as implemented in MMM 2013.25 This procedure revealed the interspin distance distribution of HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 to be populated within a range of 2.8 nm to 4.1 nm, readily accessible by DEER spectroscopy. A subsequent energy minimization of the enzyme's crystal structure using YASARA's built-in function (see ref.26) shifted this distance range to slightly higher values with a distribution between 2.9 nm and 4.5 nm.

In preparation of the EPR experiments, both spin-labeled enzyme variants were incubated with yeast tRNAPhe substrates that represent the individual extension intermediates during CCA-addition, i.e. tRNA lacking CCA (tRNA) as well as tRNA-C and tRNA-CC. Furthermore, NTP analogues α,β-methylene ATP (ATPa) and α,β-methylene CTP (CTPa) were added to the corresponding tRNA substrates, in order to trap (or freeze) individual steps of the reaction cycle. Due to the non-hydrolyzable character of these analogues, the enzymes were trapped in a pre-catalysis state. Using this approach, distances between label positions H87R1 and C334R1 were determined for each step of the CCA-addition. DEER measurements for both enzyme versions were performed with the apo states as well as in the presence of individual substrates (tRNA; tRNA + CTPa; tRNA-C + CTPa; tRNA-CC; tRNA-CC + ATPa) to detect interdomain movements within the enzymes upon tRNA and nucleotide binding. The resulting dipolar evolution functions were background-corrected and normalized. Tikhonov regularization and parameter validation as implemented in DEERAnalysis 2013 (see ref.27) were used to determine interspin distance distributions. With a modulation depth of 0.48 for HsaCCA and 0.55 for HsaCCA D139A (Fig. 4A), the number of interacting spins was calculated to be 2.2 and 2.4, respectively.

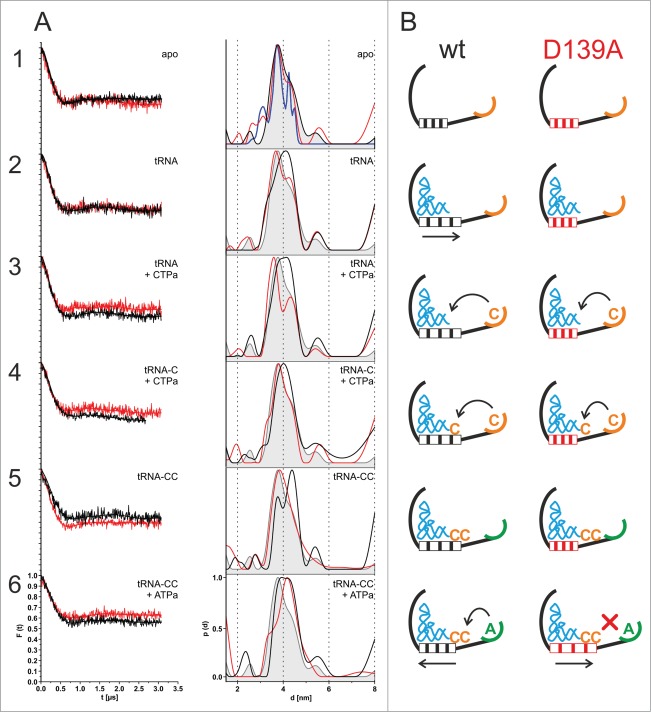

Figure 4.

(A) DEER experiments and measured interspin distance distributions. Left column: Background corrected form factors F(t) of the averaged DEER traces of HsaCCA H87CR1/C334R1 (black, thin lines) and HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1 (red, thin lines) for different substrate incubations. Fitted traces for HsaCCA H87CR1/C334R1 (black, bold lines) and HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1 (red, bold lines) were used to calculate the corresponding interspin distance distributions. Right column: Amplitude-normalized interspin distance distributions for HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1 (black line) and HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1 (red line) for different substrate incubations. The area of the distance distribution for apo HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 (light grey) is displayed as a visual reference for all distance distributions, while the calculated interspin distances for apo HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 (blue line) are only shown in the first distance distribution. (B) Mechanistic model for different motif C states during CCA-addition. As a spring element, motif C is involved in the adjustment of the catalytic core and the tRNA binding site for the individual reaction steps. In the wt enzyme, motif C (striped box, black) is expanded upon tRNA binding and remains in this conformation for both C-adding steps. In this conformation, the enzyme provides enough space for the growing tRNA. Upon ATP binding, motif C undergoes a slight contraction that might be required for A incorporation and/or limiting the number of added nucleotides. In the D139A enzyme variant (red), motif C (striped box, red) shows no expansion upon tRNA and/or nucleotide binding, even with a growing CC-end on the tRNA substrate. Only in the terminal step, the spring element is significantly extended, leading to an orientation of the tRNA primer end relative to the bound ATP that impedes an incorporation of this nucleotide, resulting in a strongly reduced A-adding activity.

The resulting distance distribution for the apo state of HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 shows a maximum at 3.7 nm and a shoulder at 4.2 nm (Fig. 4A; 1, black curve), within an estimated error of 0.1 nm. The observed distances agree well with the calculated distribution range for the interspin distances of a monomeric form of HsaCCA. After incubation of HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 with tRNA, the maximum is shifted to 4.2 nm (Fig. 4A; 2). This shift can also be observed upon the addition of tRNA and the non-hydrolyzable analogue of CTP (CTPa) (Fig. 4A; 3), tRNA-C and CTPa (Fig. 4A; 4) as well as tRNA-CC (Fig. 4A; 5). When the non-hydrolyzable ATP analogue (ATPa) was added to HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 and tRNA-CC, two equal populations at 3.7 nm and 4.2 nm are observed (Fig.4A; 6).

The corresponding distance distributions for HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1, carrying the aspartate to alanine mutation in motif C, were investigated. The apo state of this variant is almost identical to the distance distribution of the apo HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1, with a maximum at 3.7 nm and a shoulder at 4.3 nm (Fig. 4A; 1, red curve). Interestingly, the addition of tRNA (Fig. 4A; 2), tRNA and CTPa (Fig. 4A; 3), tRNA-C and CTPa (Fig. 4A; 4) as well as tRNA-CC (Fig. 4A; 5) has no significant effect on the observed distances. The distance distributions still resemble the apo state and therefore differ from the changes observed for the wild-type enzyme HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 incubated with the same substrates. The presence of tRNA-CC and ATPa, however, changed the distance distribution in HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1, leading to larger distances with a maximum at 4.2 nm and a shoulder at 3.3 nm (Fig.4A; 6). In comparison with the wild-type enzyme, the component for the larger distance is equal in its mean value, distribution width and amplitude. In contrast, the component for the smaller distance is significantly smaller in both its mean value and amplitude.

To investigate the contribution of ATPa to the interdomain movements observed upon addition of tRNA-CC and ATPa, HsaCCA D139A/H87CR1/C334R1 was incubated with ATPa only. The presence of ATPa yields the same distance distribution as the apo states of HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 and HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1.

Rigid-body docking simulation with HsaCCA and tRNA

A macromolecular rigid-body docking of the wild type enzyme and its cognate substrate was simulated to further investigate the interaction of tRNA and the spin-labeled enzyme. With the resulting best matches of the tRNA docked to the enzyme, the distance distributions based on a rotamer library approach were then calculated and analyzed for HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1. Three different types of tRNA orientations could be observed: The energetically most favorable orientation shows both the acceptor stem and the T arm of the tRNA to be interacting with the enzyme's body domain, with the tRNA 3′-end pointing towards the catalytic site. In the other orientations, the 3′-terminus of the tRNA was rotated either clockwise or counter-clockwise by an angle of approximately 90 degrees, while still retaining the interaction of the acceptor stem and T arm with the body domain of the enzyme. None of the tRNA orientations indicates a direct interaction of the spin label side chain H87R1 with the tRNA, but instead suggests a close proximity of C334R1 to the substrate. Interestingly, the calculated distance distributions between the spin label side chains showed only a possible, but not a mandatory influence of the tRNA substrate on the population ratios of the rotamers, indicating a well-defined positioning of the tRNA on the enzyme body domain, exposing either the nucleotide backbone or the nucleotide grooves towards C334R1. However, we did not observe systematic shifts of our calculated distance distributions to smaller or larger distances in any case.

The D139A mutation in motif C has no measurable effect on tRNA binding

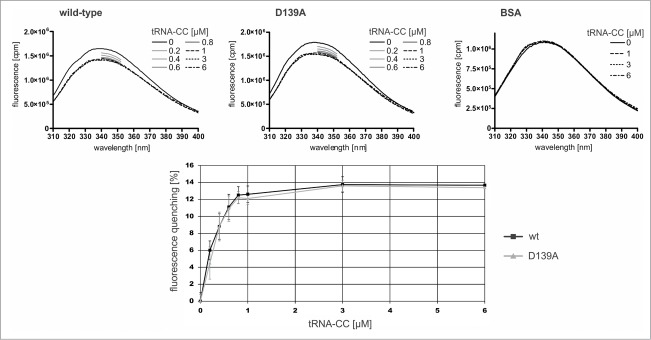

The EPR data prove that the D139A mutation in motif C has an effect on the interdomain movement during CCA-addition. However, differences in the individual substrate binding affinities of wt and D139A could explain the weak efficiency in the addition of the terminal A residue to tRNA-CC as well. Interestingly, the ATP binding is not hampered by the D139A mutation proven by a wt-like KM value (Fig. 2). Since it has repeatedly been reported that class II CCA-adding enzymes show a rather weak interaction with their tRNA substrates, the determination of binding constants based on electrophoretic mobility shift or surface plasmon resonance assays were not feasible.21,28 On the other hand, it was shown that the binding of a large substrate such as a tRNA can lead to a quenching of the tryptophan fluorescence intensity of the enzyme.18 Hence, an analysis based on fluorescence quenching allows at least a careful interpretation of relative tRNA binding differences between wild-type and mutant CCA-adding enzymes.18

The human CCA-adding enzyme carries four tryptophan residues at positions 116, 211, 353, and 387. This enabled us to monitor the reduction of fluorescence upon binding of increasing amounts of tRNA-CC in the presence of 100 μM ATPa (Fig. 5). In the wild-type enzyme, the intensity of the fluorescence signal was reduced by 12.6 % (+/− 0.9) upon the addition of tRNA-CC to a concentration of 1 μM, indicating binding of the tRNA to the enzyme. Increasing the tRNA-CC concentration to up to 6 μM had no further effect on the fluorescence quenching. In the case of the D139A variant, almost identical values were obtained, leading to a reduction of 12.1 % (+/- 0.7). These differences are statistically not significant (p = 0.7). A negative control for our fluorescence quenching experiments, a CCA-adding enzyme variant that does not bind to the tRNA-CC substrate, is not available. The removal of the C-terminal tRNA-binding domain would lead to a loss of 50-75 % of the available tryptophan residues, rendering such a variant not suitable for fluorescence quenching experiments. Instead, a bovine serum albumin preparation was used as a negative control in the quenching assays, as it known that it does not interact with tRNA.29 In our fluorescence measurements, BSA showed no significant signal reduction, indicating that the quenching effect observed for wt and D139A in the presence of tRNA is not the result of unspecific tRNA binding (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Tryptophan fluorescence of wild-type CCA-adding enzyme of H. sapiens and the variant carrying the motif C mutation D139A. Upon addition of yeast tRNAPhe-CC to 1 μM concentration, the fluorescence spectra of both enzyme forms show identical signal quenching (according to student's t-test, none of the values show a significant difference between wt and D139A variant). A further increase in tRNA-CC concentration (3 μM, 6 μM) does not lead to a further signal reduction. As a negative control, BSA was incubated with the corresponding tRNA-CC concentrations. For tRNA concentrations between 0.2 and 1 μM, the fluorescence signal was monitored from 340 to 352 nm. Neither concentration lead to any fluorescence quenching, indicating that the signal reduction of the CCA-adding enzyme variants is not a result of unspecific tRNA binding.

In conclusion, the substrate affinities of wt and D139A are very similar, indicating that the mutation D139A in motif C does not negatively affect the interaction with the tRNA-CC or ATP. Hence, the reduction in A-addition catalyzed by the mutant enzyme may be the result of the differences in the interdomain movements observed by EPR spectroscopy.

Discussion

Class II CCA-adding enzymes have an essential function in the cell and are commonly defined by a set of five conserved motifs (Fig. 1A).6,8,12,30 In addition to this sequence signature, a highly flexible loop element, located between motifs A and B, is involved in switching the enzyme's specificity from C- towards A-addition during synthesis.16,17 For four of the five signature motifs, a specific function could be identified, while motif C represents one of the less characterized catalytic core elements.31–35 Molecular modeling data of the human CCA-adding enzyme (HsaCCA) as well as the crystal structure of a closely related A-adding enzyme form A. aeolicus excluded a direct interaction with tRNA or nucleotide substrates (Fig. 1B)10,16 The first evidence that motif C contributes to an efficient CCA-addition came from the analysis of a temperature-sensitive mutation in the yeast CCA-adding enzyme.18,20,36

As the exact function of this motif was still unclear, the functional relevance of the three highly conserved positions D139, G143 and R153 in the human enzyme was investigated. While the amino acid replacement at positions G143 and R153 with alanine had no effect on the CCA-addition, the D139A variant showed a strong reduction in A-addition, indicating that motif C has a key function for this terminal reaction step during CCA-addition. One possibility for this function would be to adjust the nucleotide binding pocket for ATP specificity, similar to the role of the flexible loop element.16 Accordingly, an increase in the KM value for ATP would indicate that, due to the impeded specificity switch, the binding of ATP is affected. However, the kinetic analysis of A-addition shows that this value is almost identical to that of the wt enzyme, indicating that ATP binding is obviously unaffected by the mutation (Fig. 2). kcat, on the other hand, shows a 15-fold reduction in the D139A variant compared to the wt enzyme. This implies that the catalytic step per se or conformational steps preceding catalysis are affected. An explanation for this observation could be a reduced binding of the tRNA molecule as the second reaction substrate. However, the tryptophan fluorescence measurements performed according to Shan et al. (see ref.18) indicate a similar binding behavior for both wt and D139A mutant enzyme forms, showing that the motif C mutation has no impact on the affinity for the tRNA-CC substrate (Fig. 5). Hence, it is very likely that this motif is involved in a structural reorganization of the enzyme during CCA-addition that brings both reaction partners ATP and tRNA-CC into the required close vicinity for addition of the A residue.

Another part of the enzyme where mutations lead to a similar limitation in A-addition is the flexible loop element (between motifs A and B, Fig. 1A) that is required for the rearrangement of the nucleotide binding pocket in order to switch the enzyme's specificity from CTP towards ATP.16 While it seems that this loop directly interacts with the nucleotide binding pocket and probably contributes to locally restricted enzyme movements, motif C might coordinate more global domain arrangements, as it neither interacts with the nucleotide binding pocket nor the tRNA binding region. Indications for such domain movements are the dissolving of co-crystals consisting of a tRNA nucleotidyltransferase and tRNA upon the addition of ATP as well as the reduced A-addition due to an increased viscosity of the reaction buffer.10,11

Accordingly, EPR studies of the individual reaction steps represented by specifically spin-labeled enzyme forms in the presence of tRNA substrates and nucleotide analogues should identify motif C-dependent domain movements during catalysis. The DEER experiments with HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 and HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1 prove a monomeric state of our HsaCCA constructs in solution, which is supported by the number of interacting spins determined and the high degree of consistency between the simulated distance distribution in a single monomer (H87R1-C334R1) and our experimental results. In the crystal structure of the human enzyme, the residue C344 was found to be involved in an interprotomer disulfide bond.15 However, as the dimeric crystal structure of the closely related CCA-adding enzyme from Geobacillus stearothermophilus shows a significantly different orientation of the monomers, the disulfide bond in the human enzyme probably represents a crystallization artifact.8,15 The corresponding cysteine is missing in our constructs, limiting possible interprotomer interactions.

The asymmetric double-peak observed in the apo states of both HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 and HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1 indicates an equilibrium between two rotameric ensembles of the spin label side chains or two conformational states of the protein, unequally populated upon freezing in liquid nitrogen. The crystal structure shows both target sites for the MTSSL to be well-ordered, indicating a limited backbone flexibility and allowing for distinct rotamer conformations. Furthermore, we observe ligand-induced conformational changes for both wt and mutant enzyme. For HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1, the conformational equilibrium seems to be generally repopulated towards the larger distances upon addition of the different tRNA substrates, suggesting localized changes in the spin labels’ immediate environments due to the interactions of tRNA.

The change in the population ratios of the rotamers for HsaCCA and HsaCCA D139A upon addition of tRNA can be interpreted as a result of different substrate interactions with the enzyme, affecting both substrate affinity and catalysis. Since HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 shows an alteration in the distance distribution upon tRNA binding, the tRNA might be interacting directly with the spin label C334R1, which is in contrast to the results of our docking experiments. Alternatively, the tRNA might also be influencing the structural equilibrium indirectly through limited local rearrangements of body domain upon tRNA binding. However, despite the differences in the distance distributions of HsaCCA H87R1/C334R1 and HsaCCA D139A/H87R1/C334R1 (Fig. 4A; 2), the C-addition is undisturbed in both enzymes. This catalytic nucleotide addition requires a well-defined positioning of the tRNA substrate and enforces the 3′-end of the tRNA to interact with the head group of the enzyme, leading to a sterically enforced reorientation of this domain. Upon additional CTPa binding, the head domain is re-orientated again (Fig. 4A; 3). In contrast, HsaCCA D139A shows no alteration in the distance distribution upon tRNA binding compared to its apo state. We therefore conclude that the binding of the tRNA by HsaCCA D139A has a different effect compared to HsaCCA. Similarly, no change in spin label distance is observed for the HsaCCA D139A in the presence of tRNA-C and CTPa, while the wt enzyme still shows a slightly increased distance (Fig. 4A; 4). Upon addition of tRNA-CC to HsaCCA and HsaCCA D139A, the difference in the interdomain distances is most evident. The wt enzyme is found in an orientation with an increased spin label distance, while HsaCCA D139A shows no evident change in the interdomain distances (Fig. 4A; 5). However, in the presence of tRNA-CC and ATPa, only in HsaCCA two equally populated rotamer ensembles can be observed (Fig. 4A; 6). This is in contrast to HsaCCA D139A, where only the rotamer population corresponding to a larger distance distribution can be found. We conclude that the difference between interdomain movements of HsaCCA and HsaCCA D139A is most evident in the presence of tRNA-CC (Fig.4A; 5). Motif C is clearly involved in these intramolecular domain movements and might therefore be a crucial structural element during catalysis.

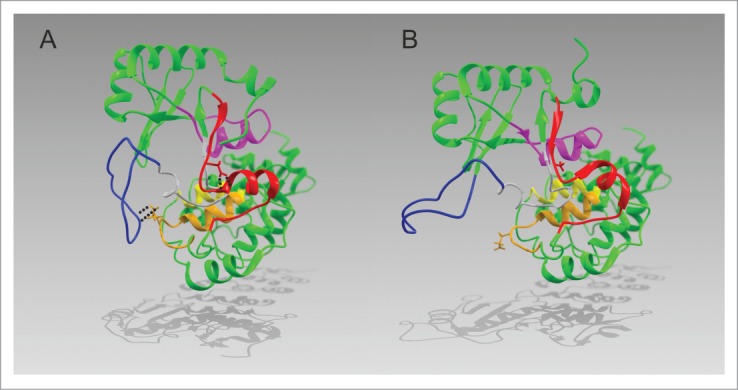

As the polymerizing enzyme does not translocate along its tRNA substrate (see ref.28), the growing 3′-end of the tRNA has to be scrunched in the catalytic core for proper accommodation.8 Our data suggest that motif C contributes to this substrate-specific adaptation by modulating the interdomain flexibility of the enzyme. We therefore propose a model, where motif C acts as a spring element located between the head (NTP-binding) and the body domain (tRNA-binding) of the CCA-adding enzyme (Fig. 4B). While this motif is not directly involved in substrate (tRNA, NTPs) binding, it is an essential element required for the proper orientation of the two reactants within the catalytic core. Upon binding of the tRNA, the spring element is stretched, and the catalytic core of the enzyme is adjusted to accommodate the growing tRNA, permitting the selective addition of three residues. Upon incorporation of the first two C residues, this adjustment is not changed, and only upon binding of ATP, a slight contraction is observed and might contribute to the termination of the reaction. In the HsaCCA D139A, carrying the mutant motif C, the spring element is not fully functional, and tRNA binding does not result in an expanded enzyme. Yet, the growing tRNA finds enough space to allow the addition of two C residues. Only upon ATP binding, the enzyme is considerably expanding. However, now the distance and/or the orientation of the two reactants tRNA-CC and bound ATP is distorted and does not allow for an efficient nucleophilic attack of the tRNA's 3′-OH group on the bound ATP. Hence, the mutant enzyme shows a strongly reduced A-adding activity, while the substrate specificity for both tRNA-CC and ATP remains unaffected. It is very likely that this spring element does not represent an isolated functional unit, but acts in concert with the region of two neighboring α-helices (h8, h11) forming a second spring stabilized by several hydrogen bonds that also helps to define the number of nucleotides added to the tRNA (Fig. 3A).9

In the crystal structure of the human CCA-adding enzyme, the aspartate residue at position 139 is located at the N-terminal top of a small α-helix formed by motif C and interacts with Nα of the backbone at positions G143 and Y144 (Fig. 6). This type of interaction has been described as helix-capping and is essential for the stability of α-helical structures in proteins.37,38 Hence, replacing D139 by alanine presumably disrupts this capping interaction, destabilizing the structural organization and the correct positioning of the corresponding helix. Replacing the interacting partner G143, however, shows no such invasive effect, as the Nα in the protein backbone remains present. Obviously, this contribution of D139 in helix-capping is directly correlated to the described spring function of motif C during CCA-addition. Molecular dynamics simulations of HsaCCA and HsaCCA D139A indicate a second important contribution of D139 to the catalytic activity of the enzyme: The replacement of aspartate by alanine in silico leads to a tilting motion of the head domain away from motif C. This is accompanied by a reorientation of the upstream located β-sheet region in the head domain, forcing the flexible loop element to lose its contact to the nucleotide binding pocket, where it is required for switching the enzyme's specificity from CTP towards ATP. This scenario suggests that the spring element (consisting of motif C and the surrounding α-helices) collaborates with the loop element to stabilize and adjust the position of the head domain with respect to the enzyme's body domain for a specific nucleotide binding and incorporation. Such a well-coordinated movement of the two enzyme domains couples the binding of the tRNA-CC primer with the specificity switch of the binding pocket, resulting in the addition of the terminal A residue and a complete CCA-end.

Figure 6.

Proposed structural model derived from the comparison of the differences between HsaCCA and HsaCCA D139A as revealed after a 7.5 ns MD simulation (YASARA).26 All motifs are colored according to Fig. 1. (A) In HsaCCA, the aspartate residue at position 139 (stick model, red) forms two hydrogen bonds with the backbone Nα positions of glycine 143 and tyrosine 144. This interaction stabilizes the α-helical conformation and contributes to the spring function of motif C. The flexible loop (blue) forms a salt bridge to glutamate 166 (stick representation, orange) located in motif D. (B) In HsaCCA D139A the spring function of motif C is impaired due to the exchange of D139 with alanine (stick representation, red), removing the stabilizing hydrogen bonds. As a consequence, the catalytic head domain rotates from its initial position and the flexible loop (blue) disconnects from E164 (stick model, orange). The changes in the Cα- Cα distances between H87 and C334 are insignificant (HsaCCA: 40.1 Å, HsaCCA D139A: 40.8 Å).

In the CCA-adding enzyme of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the replacement of a glutamic acid residue at position 189, also located in the N-terminal part of motif C, was shown to lead to a temperature-sensitive enzyme with reduced catalytic activity.18,20 However, as no kinetic parameters were determined, it is impossible to directly compare these mutants with the human D139 variant. Furthermore, sequence alignments as well as structural overlays based on the crystal structures of the human and a bacterial CCA-adding enzyme from G. stearothermophilus in combination with a structural model of the yeast enzyme generated using I-TASSER software (see ref.39), indicate that E189 is not the positional homologue of the human D139 (Fig. S1). Instead, the neighboring D190 seems to represent this conserved position. This aspartate residue is present in all structures at the same position, interacting with the same N-terminal part of the neighboring α-helix. A corresponding position to the yeast E189, on the other hand, is not found in the other CCA-adding enzymes and is very likely not involved in helix-capping. Hence, the observed effects of mutating E189 in the yeast enzyme do not correspond to the effects of D139 in the human enzyme.

In conclusion, a defined flexibility is a key feature of class II CCA-adding enzymes required to adjust the catalytic core to accommodate a growing tRNA and the corresponding nucleotides CTP or ATP for incorporation. Besides the flexible loop element involved in defining the enzyme's nucleotide specificity, the spring function of motif C is contributing to the correct spatial arrangement of the reactants tRNA and NTP. Obviously, an intricate interplay of the catalytic core elements together with the motif C spring and the flexible loop is coordinating the domain movements of this enzyme. Further experiments regarding defined enzyme domain movements will help to understand the process of this essential reaction in more detail.

Materials and Methods

Construction of mutant variants

The cDNA for the human CCA-adding enzyme was cloned as described.40 Point mutations were introduced into the coding sequence using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene).

Expression, purification and spin labeling

N-terminally His-tagged enzyme variants were overexpressed and purified by FPLC as previously described.17 Fractions containing protein were identified via SDS-PAGE, pooled and dialyzed against 20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 30 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 20 % glycerol.

To tag the enzyme with (1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetra-methyl-pyrroline-3-methyl) methanethiosulfonate spin label (MTSSL), the soluble protein fraction was first incubated in labeling buffer (20 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and loaded onto a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare). The bound protein was washed with 50 ml labeling buffer in the absence of β-mercaptoethanol and incubated on the column over night at 4°C in the same buffer containing 1 mM MTSSL. Excessive MTSSL was removed with 50 ml of labeling buffer without β-mercaptoethanol and the protein was eluted and dialyzed as described.17

tRNA preparation

For the preparation of radioactively labeled tRNA lacking the CCA terminus or ending with a partial CCA-end, transcription was carried out in the presence of α32P-ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) as described before.41,42 Alternatively, products of a scaled up transcription reaction were separated on a XK 16/60 Superdex 200 pg column (GE Healthcare; buffer: 10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 6.5) using an ÄKTApure 25 (GE Healthcare).43

Activity test and kinetic analysis

Standard activity assays were performed according to Neuenfeldt et al.17 Reactions were stopped by ethanol precipitation. Reaction products were separated on a 10 % denaturing PAA gel and visualized by autoradiography.

Steady-state kinetic analysis was conducted as described (see ref.33,35) with 3 μM tRNA-CC and a total of 3.5 μCi of α32P-ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) per reaction. ATP was titrated between 0.005 mM and 0.6 mM and reactions were terminated after 10 min.

Fluorescence quenching analysis

To compare the tRNA binding behavior between the wt HsaCCA enzyme and the D139A variant, tryptophan fluorescence spectra were measured for the unlabeled enzymes in the presence of the non-hydrolyzable NTP analogue α,β-methylene ATP (ATPa, at 100 μM; Jena Bioscience) and varying concentrations of yeast tRNAPhe-CC transcript according to Shan et al.18 using a FluoroLog (Horiba Scientific). In a total volume of 1.2 ml, the recombinant enzymes or BSA (NEB B9001S) as negative control were diluted to concentrations of 200 μM (HsaCCA wt and HsaCCA D139A) and 450 μM (BSA), respectively. tRNA-CC was titrated to final concentrations of 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1, 3 and 6 μM. At each step, a triplet of fluorescence spectra was recorded, in the case of 1 to 6 μM tRNA-CC from 310 nm to 400 nm, for the intermediate values between 0.2 and 1 μM from 340 to 352 nm (100 nm/min, 1 nm data sampling interval, 5 nm excitation and emission slit width, 295 nm excitation wavelength). Inner filter effects were accounted for as described (see ref.18) and the buffer signal was subtracted. Volume changes and bleaching effects of each protein were taken into account.

EPR spectroscopy

For spin-labeled HsaCCA enzymes, 25-45 μl of sample solution, including 20 %(V/V) glycerol, were loaded into EPR quartz capillaries with an outer diameter of 3 mm. Enzyme preparations were incubated with tRNA transcripts and non-hydrolyzable NTP analogues under conditions that ensure a complete substrate turnover (4-25°C; 2-20 min.) prior to freezing in liquid nitrogen and insertion into the resonator. Incubation for given amounts of time and temperature is excessive for complete CCA-addition on tRNA (data not shown). The final concentrations of tRNA, tRNA-C and tRNA-CC were adjusted to be in a moderate excess of the enzyme concentrations (120 %), whereas the final concentrations of α,β-methylene ATP (Jena Bioscience) and α,β-methylene CTP (Jena Bioscience) were significantly higher (300 %). DEER experiments were performed at 50 K and X-band frequencies (∼9.4 GHz) using a Bruker Elexsys 580 spectrometer with a 3 mm split ring resonator (ER 4118X-MS3, Bruker) in combination with a continuous flow cryostat (EPR900, Oxford Instruments). The temperature was controlled using an ITC 503S (Oxford Instruments). All interspin distance measurements were performed using the four-pulse DEER sequence: π/2(νobs) - τ1 – π (νobs) – t’ – π (νpump) – (τ1 + τ2 – t’) – π (νobs) - τ2 – echo with observer pulse lengths of 16 ns for π/2 and 32 ns for π pulses and a pump pulse length of 12 ns. A two-step phase cycling (+‹x›, -‹x›) was performed on π/2 (νobs). The time t’ was varied, whereas τ1 and τ2 were kept constant. The dipolar evolution time is then given by t = t’ – τ1. The data was analyzed for t > 0 only. The resonator was overcoupled and the pump frequency νpump was set to the center of the resonator dip (i.e. at the maximum of the nitroxide EPR spectrum) whereas the observer frequency νobs was 65-75 MHz higher (at the local low-field maximum of the EPR spectrum). Proton modulation was averaged by adding traces at eight different τ1 values, starting at τ1,0 = 200 ns and incrementing by Δτ1 = 8 ns. Data points were recorded in 8 ns time steps. The total measurement time for each sample was 24-48 h. Tikhonov regularization and parameter validation were performed with DEERAnalysis 2013.27 Numerical values for the peaks of the interspin distances were derived by the manual fit of Gaussians to the distance distributions.

Macromolecular docking simulation

Starting with the crystal structure of HsaCCA (see ref.15), the flexible loop was homology-modeled based on the crystal structure of Geobacillus stearothermophilus CCA-adding enzyme using MODELLER.8,44 For the macromolecular rigid-body docking with AutoDock Vina (see ref.45), the homology-model of the HsaCCA and the crystal structure of the yeast tRNA for phenylalanine (see ref.46) were energy-minimized with YASARA (see ref.27) and joined in a search space cuboid with an edge length of 10.0 nm. The search space was centered to enable a free orientation of the tRNA around the catalytic site of the HsaCCA.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sonja Bonin and Tobias Friedrich for expert technical assistance and Paul B.M. Joyce for providing us the protocol for tryptophan fluorescence quenching analysis.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1. Deutscher MP. tRNA Nucleotidyltransferase. Boyer PD ed Nucl Acid Part B Acad Press 1982:183-215 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sprinzl M, Cramer F. The-C-C-A end of tRNA and its role in protein biosynthesis. Prog Nucl Acid Res Mol Biol 1979; 22:1-69; PMID:392600; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60798-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holm L, Sander C. DNA polymerase beta belongs to an ancient nucleotidyltransferase superfamily. Trend Biochem Sci 1995; 20:345-7; PMID:7482698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aravind L, Koonin EV. DNA polymerase beta-like nucleotidyltransferase superfamily: identification of three new families, classification and evolutionary history. Nucleic Acids Res 1999; 27:1609-18; PMID:10075991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martin G, Keller W. RNA-specific ribonucleotidyl transferases. RNA 2007; 13:1834-49; PMID:17872511; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.652807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yue DX, Maizels N, Weiner AM. CCA-adding enzymes and poly(A) polymerases are all members of the same nucleotidyltransferase superfamily: characterization of the CCA-adding enzyme from the archaeal hyperthermophile Sulfolobus shibatae. J Theor Biol 1996; 2:895-908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tomita K, Yamashita S. Molecular mechanisms of template-independent RNA polymerization by tRNA nucleotidyltransferases. Frontiers Genet 2014; 5:36; PMID:24596576; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/fgene.2014.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li F, Xiong Y, Wang JM, Cho HD, Tomita K, Weiner AM, Steitz TA. Crystal structures of the Bacillus stearothermophilus CCA-adding enzyme and its complexes with ATP or CTP. Cell 2002; 111:815-24; PMID:12526808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Toh Y, Takeshita D, Numata T, Fukai S, Nureki O, Tomita K. Mechanism for the definition of elongation and termination by the class II CCA-adding enzyme. EMBO J 2009; 28:3353-65; PMID:19745807; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2009.260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tomita K, Fukai S, Ishitani R, Ueda T, Takeuchi N, Vassylyev DG, Nureki O. Structural basis for template-independent RNA polymerization. Nature 2004; 430:700-4; PMID:15295603; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature02712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim S, Liu C, Halkidis K, Gamper HB, Hou Y. Distinct kinetic determinants for the stepwise CCA addition to tRNA. RNA 2009; 15:1827-36; PMID:19696158; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.1669109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Betat H, Rammelt C, Mörl M. tRNA nucleotidyltransferases: ancient catalysts with an unusual mechanism of polymerization. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010; 67:1447-63; PMID:20155482; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-010-0271-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Steitz TA, Smerdon SJ, Jäger J, Joyce CM. A unified polymerase mechanism for nonhomologous DNA and RNA polymerases. Science 1994; 266:2022-5; PMID:7528445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Steitz TA. DNA- and RNA-dependent DNA polymerases. Curr Opin Struct Biol 1993; 3:31-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0959-440X(93)90198-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Augustin MA, Reichert AS, Betat H, Huber R, Mörl M, Steegborn CA. Crystal structure of the human CCA-adding enzyme: Insights into template-independent polymerization. J Mol Biol 2003; 328:985-94; PMID:12729736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoffmeier A, Betat H, Bluschke A, Gunther R, Junghanns S, Hofmann HJ, Mörl M. Unusual evolution of a catalytic core element in CCA-adding enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:4436-47; PMID:20348137; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkq176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neuenfeldt A, Just A, Betat H, Mörl M. Evolution of tRNA nucleotidyltransferase: A small deletion generated CC-adding enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105:7953-8; PMID:18523015; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0801971105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shan X, Russell TA, Paul SM, Kushner DB, Joyce PBM. Characterization of a temperature-sensitive mutation that impairs the function of yeast tRNA nucleotidyltransferase. Yeast 2008; 25:219-33; PMID:18302315; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/yea.1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamashita S, Takeshita D, Tomita K. Translocation and Rotation of tRNA during Template-Independent RNA Polymerization by tRNA Nucleotidyltransferase. Structure 2013; 22:315-25; PMID:24389024; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.str.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goring ME, Leibovitch M, Gea-Mallorqui E, Karls S, Richard F, Hanic-Joyce PJ, Joyce PB. The ability of an arginine to tryptophan substitution in saccharomyces cerevisiae tRNA nucleotidyltransferase to alleviate a temperature-sensitive phenotype suggests a role for motif C in active site organization. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1834:2097-106; PMID:23872483; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tretbar S, Neuenfeldt A, Betat H, Mörl M. An inhibitory C-terminal region dictates the specificity of A-adding enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108:21040-5; PMID:22167803; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1116117108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Klare JP. Site-directed spin labeling EPR spectroscopy in protein research. Biol Chem 2013; 394:1281-300; PMID:23912220; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1515/hsz-2013-0155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klare JP, Steinhoff H. Spin labeling EPR. Photosynthesis Res 2009; 102:377-90; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11120-009-9490-7; PMID:19728138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steinhoff H. Inter- and intra-molecular distances determined by EPR spectroscopy and site-directed spin labeling reveal protein-protein and protein-oligonucleotide interaction. Biol Chem 2004; 385:913-20; PMID:15551865; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1515/BC.2004.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Polyhach Y, Bordignon E, Jeschke G. Rotamer libraries of spin labelled cysteines for protein studies. Phys Chem Chem Phys : PCCP 2011; 13:2356-66; PMID:21116569; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1039/c0cp01865a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krieger E, Koraimann G, Vriend G. Increasing the precision of comparative models with YASARA NOVA–a self-parameterizing force field. Proteins 2002; 47:393-402; PMID:11948792; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jeschke G, Chechik V, Ionita P, Godt A, Zimmermann H, Banham J, Timmel CR, Hilger D, Jung H. DeerAnalysis 2006—a comprehensive software package for analyzing pulsed ELDOR data. Appl Magn Reson 2006; 30:473-98. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shi PY, Maizels N, Weiner AM. CCA addition by tRNA nucleotidyltransferase: polymerization without translocation? EMBO J 1998; 17:3197-206; PMID:9606201; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scheibe M, Bonin S, Hajnsdorf E, Betat H, Mörl M. Hfq stimulates the activity of the CCA-adding enzyme. BMC Mol Biol 2007; 8:92; PMID:17949481; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2199-8-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xiong Y, Steitz TA. A story with a good ending: tRNA 3′-end maturation by CCA-adding enzymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2006; 16:12-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cho HD, Verlinde C, Weiner AM. Reengineering CCA-adding enzymes to function as (U,G)- or dCdCdA-adding enzymes or poly(C,A) and poly(U,G) polymerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:54-9; PMID:17179213; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0606961104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hanic-Joyce PJ, Joyce Paul BM. Characterization of a gene encoding tRNA nucleotidyltransferase from candida glabrata. Yeast 2002; 19:1399-411; PMID:12478587; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/yea.926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Just A, Butter F, Trenkmann M, Heitkam T, Mörl M, Betat H. A comparative analysis of two conserved motifs in bacterial poly(A) polymerase and CCA-adding enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res 2008; 36:5212-20; PMID:18682528; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkn494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Keller W, Martin G. Mutational analysis of mammalian poly(A) polymerase identifies a region for primer binding and a catalytic domain, homologous to the family X polymerases, and to other nucleotidyltransferases. EMBO J 1996; 15:2593-603; PMID:8665867 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lizano E, Scheibe M, Rammelt C, Betat H, Mörl M. A comparative analysis of CCA-adding enzymes from human and E. coli: differences in CCA addition and tRNA 3′-end repair. Biochimie 2008; 90:762-72; PMID:18226598; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aebi M, Kirchner G, Chen JY, Vijayraghavan U, Jacobson A, Martin NC, Abelson J. Isolation of a temperature-sensitive mutant with an altered tRNA nucleotidyltransferase and cloning of the gene encoding tRNA nucleotidyltransferase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 1990; 265:16216-20; PMID:2204621 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aurora R, Rose GD. Helix capping. Protein Sci 1998; 7:21-38; PMID:9514257; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Makhatadze GI. Thermodynamics of alpha-helix formation. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2006; 72:199-+; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)72008-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protoc 2010; 5:725-38; PMID:20360767; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nprot.2010.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reichert AS, Thurlow DL, Mörl M. A eubacterial origin for the human tRNA nucleotidyltransferase? Biol Chem 2001; 382:1431-8; PMID:11727826; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1515/BC.2001.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mörl M, Lizano E, Willkomm DK, Hartmann RK. Production of RNAs with Homogeneous 5′- and 3′-Ends. In: Hartmann RK, Bindereif A, Schön A, Westhof E, eds. Handbook of RNA Biochemistry. Weinheim, Chichester: Wiley-VCH; John Wiley, 2012:22-35. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schürer H, Lang K, Schuster J, Mörl M. A universal method to produce in vitro transcripts with homogeneous 3′ ends. Nucleic Acids Res 2002; 30:e56; PMID:12060694; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gnf055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim I, McKenna SA, Viani Puglisi E, Puglisi JD. Rapid purification of RNAs using fast performance liquid chromatography (FPLC). RNA 2007; 13:289-94; PMID:17179067; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.342607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol 1993; 234:779-815; PMID:8254673; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 2010; 31:455-61; PMID:19499576; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcc.21334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Klipcan L, Moor N, Finarov I, Kessler N, Sukhanova M, Safro MG. Crystal structure of human mitochondrial PheRS complexed with tRNA(Phe) in the active "open" state. J Mol Biol 2012; 415:527-37; PMID:22137894; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.