Abstract

Background

Pullulanase is an important debranching enzyme and has been widely utilized to hydrolyse the α-1,6 glucosidic linkages in starch/sugar industry. Selecting new bacterial strains or improving bacterial strains is a prerequisite and effective solution in industrial applications. Although many pullulanase genes have been cloned and sequenced, there is no report of P. polymyxa type I pullulanase gene or the recombinant strain. Meanwhile most of the type I pullulanase investigated exhibit thermophilic or mesophilic properties. There are just few reports of cold-adapted pullulanases, which have optimum activity at moderate temperature and exhibit rather high catalytic activity at cold. Previously, six strains showing distinct pullulan degradation ability were isolated using enrichment procedures. As containing novel bacterium resource and significant pullulanase activity, strain Nws-pp2 was selected for in-depth study.

Methods

In this study, a type I pullulanase gene (pulN) was obtained from the strain P. polymyxa Nws-pp2 by degenerate primers. Through optimization of induced conditions, the recombinant PulN achieved functional soluble expression by low temperature induction. The enzyme characterizations including the enzyme activity/stability, optimum temperature, optimum pH and substrate specificity were also described through protein purification.

Results

The pullulanase gene (named pulN), encoding a novel cold-adapted type I pullulanase (named PulN), was obtained from isolated strain Paenibacillus polymyxa Nws-pp2. The gene had an open reading frame of 2532-bp and was functionally expressed in Escherichia coli through optimization of induced conditions. The level of functional PulN-like protein reached the maximum after induction for 16 h at 20 °C and reached about 0.34 mg/ml (about 20 % of total protein) with an activity of 6.49 U/ml. The purified recombinant enzyme with an apparent molecular mass of about 96 kDa was able to attack specifically the α-1,6 linkages in pullulan to generate maltotriose as the major product. The purified PulN showed optimal activity at pH 6.0 and 35 °C, and retained more than 40 % of the maximum activity at 10 °C (showing cold-adapted). The pullulanase activity was significantly enhanced by Co2+ and Mn2+, meanwhile Cu2+ and SDS inhibited pullulanase activity completely. The Km and Vmax values of purified PulN were 15.25 mg/ml and 20.1 U/mg, respectively. The PulN hydrolyzed pullulan, amylopectin, starch, and glycogen, but not amylose. Substrate specificity and products analysis proved that the purified pullulanase from Paenibacillus polymyxa Nws-pp2 belong to a type I pullulanase.

Conclusions

This report of the novel type I pullulanase in Paenibacillus polymyxa would contribute to pullulanase research from Paenibacillus spp. significantly. Also, the cold-adapted pullulanase produced in recombinant strain shows the potential application.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12896-015-0215-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pullulanase type I, Paenibacillus polymyxa, Cold-adapted pullulanase, Functional expression, Enzymatic properties, Starch hydrolysis products

Background

The α-amylase family enzymes such as endo-amylases, glucoamylases, α-glucosidases and α-1,6-cleaving enzymes (pullulanase and isoamylase) have been widely used in starch-processing industries [1, 2]. Among these, pullulanase (EC 3.2.1.41), which can hydrolyze α-(1,6)-glucosidic linkages of pullulan or branched substrates is widely used in saccharification process for glucose, maltose, maltotriose and fructose production (usually used in combination with other amylolytic enzymes) [3–5]. Also, pullulanase was used in the fermentation industry to produce low carbohydrate “light beer” by adding pullulanase with fungal α-amylase or glucoamylase to the wheat during fermentation and bioethanol production [6]. Based on the substrate specificity and end product, pullulanase have been classified into five groups including (i) pullulanase type I (EC 3.2.1.41), also called the true pullulanases, specifically hydrolyses α-1,6 glycosidic linkages in pullulan or branched oligosaccharides to produce maltotriose and linear oligosaccharides (Additional file 1: Figure S1); (ii) pullulanase type II (amylopullulanase), attacks α-1,6 linkages in pullulan to produce maltotriose and α-1,4 linkages of other branched substrates to produce a mixture of glucose, maltose, and maltotriose (Additional file 1: Figure S1); (iii) pullulan hydrolase type I (neopullulanase, EC 3.2.1.135), hydrolyzing α-1,4 linkages in pullulan to produce panose (Glucose-α-1,6-Glucose-α-1,4-Glucose); (iv) pullulan hydrolase type II (isopullulanase, EC 3.2.1.57), hydrolyzing α-1,4 linkages in pullulan to produce isopanose (Glucose-α-1,4-Glucose- α-1,6-Glucose); and (v) pullulan hydrolase type III, attacks α-1,4 as well as α-1,6 glycosidic linkages in pullulan forming a mixture of maltotriose, panose and maltose [6–8].

Pullulanase is widely distributed in bacteria (Bacillus sp., Aerobacter sp., Klebsiella sp.), yeasts, fungi, plants and animals and most pullulanase are type II pullulanases [9]. A few type I pullulanases were investigated in gene level, such as Bacillus flavocaldarius KP 1228 [10], Bacillus thermoleovorans US105 [11], Anaerobranca gottschalkii [12], Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus [13], Bacillus sp. CICIM 263 [14], Thermotoga neapolitana [15] and Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5 [16]. Most of type I pullulanase investigated exhibit thermophilic or mesophilic properties. There are just few reports of cold-adapted pullulanases, which have optimum activity at moderate temperatures and exhibit rather high catalytic activity at cold [8]. Cold-adapted enzymes are promising candidates for versatile biotechnological applications especially food industry due to the reduced risk of microbial contamination, minimized energy consumption and the fact that reacting compounds are often instable at increasing temperatures [17]. Among the most industrially relevant biocatalysts are starch-hydrolyzing enzymes, such as amylase, pullulanase, glucoamylase or α-glucosidase, that are widely used in food, feed, textile, pharmaceutical and detergent industries. Cloning the novel enzymes with distinct features, especially from easily grown bacterium, are of interest for industrial applications. Paenibacillus polymyxa strains (formerly Bacillus polymyxa) are well known for their ability to produce and secrete a large number of useful extracellular enzymes [18, 19]. Although many pullulanase genes from Bacillus spp. have been cloned and sequenced, there is no gene report of type I pullulanase in P. polymyxa. Castro et al. described the microbial characterization and enzymatic property in wild strain Bacillus polymyxa MIR-23 [20]. Kim et al. report the neopullulanase gene in Paenibacillus sp. KCTC 8848P which contained 510 amino acids [21].

Previously, six strains showing distinct pullulan degradation ability were isolated using enrichment procedures. As containing novel bacterium resource and significant pullulanase activity, strain Nws-pp2 was selected in-depth study. In this study, a type I pullulanase gene (pulN) was obtained from the strain P. polymyxa Nws-pp2 which was isolated from soil of fruit market garbage dump in Shanghai, China. Through optimization of induced conditions, the recombinant PulN achieved functional soluble expression by low temperature induction. The enzyme characterizations including the enzyme activity/stability, optimum temperature, optimum pH and substrate specificity were also described through protein purification. Another impressive fact is that the cold-adapted pullulanase showing low temperature catalytic performance (similar with enzymes from psychrophilic bacteria) was cloned from the mesophilic strain which grown well at ambient temperature (37 °C). Also, this report of the novel type I pullulanase from P. polymyxa with the detailed enzymatic properties would contribute to cold-adapted pullulanase research. The novel pullulanase showing cold-adapted biochemical characteristics provides the potential value in food-processing industry applications.

Methods

Bacterial strains/plasmids and chemicals

The bacterial strains, plasmids, chemicals, and culture conditions used in this study are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1 in supplemental material. Strain Nws-pp2 (named Paenibacillus polymyxa Nws-pp2, CCTCC AB 2013352) was isolated from soil of fruit market garbage dump in Shanghai, China. Escherichia coli DH5α (Invitrogen) and plasmid pMD19-T (TaKaRa) were used for gene cloning and sequencing. Plasmids pET-28a, pET-32a and pET-42a (Novagen) were the vectors used to construct the protein expression plasmid in E. coli BL21(DE3).

Strain screening, pulN Cloning and gene analysis

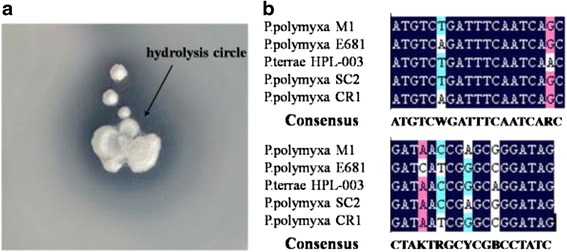

Using pullulanase screening culture, the microbes showing obviously hydrolysis circle (treated with alcohol) were isolated, purified and transferred to maintenance slants. Among these, strain Nws-pp2 showing high ratios of hydrolysis circle were selected and identified by 16S rDNA gene analysis [22, 23].

Based on the information of Paenibacillus spp. pullulanases in GeneBank, degenerate primers (pul-U:ATGTCWGATTTCAATCARC, pul-D:CTATCCBGCYCGRTKATC) for the pullulanase gene sequence were designed. According to NCBI search, the following gene sequences of predicted pullulanase from Paenibacillus spp. were analyzed to design degenerate primers (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Pullulanase in wild strain and degenerate primers design. a Hydrolysis circle on pullulanase screening culture. b Comparison of five pullulanase genes from different resource. Sequences listed include partial of type I pullulanase genes from Paenibacillus polymyxa M1 (HE577054.1), Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 (CP000154.1), Paenibacillus terrae HPL-003 (CP003107.1), Paenibacillus polymyxa SC2 (CP002213.1) and Paenibacillus polymyxa CR1 (CP006941.1)

The pullulanase gene (Genbank accession number: KJ740392) was amplified by PCR using primers pul-U/pul-D. The purified PCR product (2.5 kb) was cloned into pMD19-T and sequenced in two directions. The nucleotide sequence and predicted amino acid sequence were analyzed by the programs of Blast (NCBI, http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Enzyme Mw and pI were predicted using the ExPASy proteomic server program (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/). Multiple sequence alignments were performed using ClustalX/DNAMAN and the three-dimensional structure of this enzyme was predicted by the SWISS-MODEL server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/SWISS-MODEL.html) [22].

According to the gene analysis, we designed other primers for pET family vectors. For E. coli expression, the gene was amplified by the primers (pul-pET-U:CGCGGATCCATGTCTGATTTCAATC, pul-pET-D:CCCAAGCTTCTATCCCGCTCGATCA). After digestion by BamHI/HindIII restriction enzyme, the pulN gene was reclaimed and connected with pET-28a, pET-32a and pET-42a vectors respectively, which were digested by the same restriction endonuclease. The positive clones were selected by restriction enzyme digestion and finally confirmed by sequencing (Additional file 1: Figure S2). The recombinant plasmids pET-28-pulN, pET-32-pulN and pET-42-pulN were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). Recombinant cells (BL21-pET-28-pulN, BL21-pET-32-pulN and BL21-pET-42-pulN) were grown to saturation in LB medium supplemented with appropriate antibiotic.

Induced conditions optimization and recombinant protein purification

When the optical density at OD600 nm reached 0.6, IPTG was added to induce the lac promoter of recombinant strains. Recombinant cells in different pET plasmid (BL21-pET-28-pulN, BL21-pET-32-pulN and BL21-pET-42-pulN) were firstly selected by SDS-PAGE and enzyme analysis (induction temperature: 37 °C, induction time 24 h, IPTG concentration: 0.5 mM). The conditions of pulN overexpression (BL21-pET-28-pulN) were optimized testing different parameters: temperatures (20, 25, 30 and 37 °C), the IPTG concentrations (0.1–1.5 mM, 0.1 mM gradient increasing) and induction time (2, 4, 8, 16, 24, and 32 h).

To show the expression level of recombinant pullulanase in each sample, we diluted the precipitated cells samples in 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) to a final concentration OD600 value equal to 10. All samples including supernatant of cell lysate and precipitation of cell lysate were dispersed in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer and heated to 100 °C. Finally, proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (12.5 % acrylamide/bis-acrylamide) and stained with coomassie brilliant blue. Moreover, the uninduced transformant and transformant harboring the empty plasmid were used as negative control. Purification steps of the pullulanase were performed at 4 °C [22].

Enzyme properties analysis

The activity of PulN in pullulan hydrolysis were measured in triplicate at 35 °C in 100 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) using 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid method. Enzyme activity was determined by measuring the enzymatic release of reducing sugar from pullulan. In this assay, 250 μl of 1 % (wt/vol) pullulan (sigma) solution and 175 μl of 100 mM citrate buffer were mixed and preincubated at 35 °C in a water bath. Then 75 μl of appropriately diluted enzyme sample was added into the preheated solution and the 500 μl reaction mixture was further incubated at 35 °C for 20 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of 750 μl 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid reagent (DNS), followed by boiling for 15 min and cooled with ice-water mixture. The reaction system with the same enzyme sample added after DNS reagent was treated as the control. Activities were expressed as mean values in U (mg protein). 1 U is defined as the amount of enzyme that released 1 μmol reducing sugars (equivalent to glucose) per min under the assay conditions specified. All the pullulanase activities were converted to the whole fermentation volume (volumetric activities U or mg per ml medium). Each experiment was repeated three times and each experiment included three replicates. The average values of triplicate measurements were used as each activity value. The statistical tool Origin 8.0 was used to analyze the enzymatic properties data. All values are means ± SD from three independent experiments (repeats with SD of ≤ 5 %).

The pH optimum for PulN enzyme activity was studied over a range from pH 4.0–10.0 with pullulan as the substrate (35 °C). The pH stability of the enzyme was determined by incubating the enzyme in different buffers for 90 min and incubated at 35 °C. The following buffer systems were used: 100 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.0–6.0), 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0–7.5), 50 mM Tris-HCL buffer (pH 7.5–8.5) and 100 mM glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 8.5–10.0). The temperature optimum for the PulN enzyme activity was assayed at 10–75 °C (pH 6.0). The thermal stability of PulN was evaluated by assaying its residual activity after incubation of the enzyme at various temperatures (35, 40, 45 and 50 °C) for 300 min in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). The enzyme sample without any incubation was considered as control (100 %).

Effects of metal ions (1, 5 and 10 mM) and other reagents on enzyme activity were determined in a standard assay medium. The reaction mixtures containing the enzyme sample were incubated at 35 °C for 60 min in 100 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0. The enzyme sample without any additives was considered as control (100 %).

Kinetic parameters measurements

The kinetic parameters Km and Vmax were determined for the substrate pullulan at 35 °C in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) using DNS method. Different concentrations of pullulan (2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 12 mg/ml) were used in the standard reaction system. Samples were withdrawn from reaction system (2 min interval) and measured. The initial velocity values (the amount of maltotriose generated per minute) and substrate concentrations were transformed into Lineweaver-Burk reciprocal plots. Then, Km and Vmax were calculated from the slopes of the curves (Additional file 1: Figure S4).

Characterization of substrates specificity and hydrolysis products

The ability of the purified enzyme to hydrolyze various carbohydrates was examined at 35 °C and pH 6.0 in 100 mM citrate buffer. The carbohydrates tested were pullulan, soluble starch, amylose, amylopectin and glycogen at a concentration of 1 % (w/v). About 0.5 U enzyme was added to the different substrate, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 35 °C for 8 h. Subsequently, the reaction systems were stopped by boiling for 5 min and centrifugation for later use. The hydrolysis products on different substrate were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), respectively. Silica gels plate was used for TLC analysis. After activated at 110 °C for 1 h, prepared samples were spotted onto the plate. The plate was placed in a chamber containing a solvent system of acetic acid-N-butanol-water (1:2:1) for a while and then was withdrawn. After the plate was dried, the reducing sugar was detected using sulfuric acid solution (containing 0.3 % N-1-naphthyl-ethylenediamine and 5 % H2SO4 in methanol) at 110 °C for 10 min. The cold-adapted enzymatic property of PulN was confirmed by TLC with the industrial enzyme as a control (Promozyme; Novozymes A/S). The enzymes (about 0.5 U) were added to the pullulan substrate, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 0, 20 and 40 °C for 120 min. The hydrolysis products were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Waters analysis column (Ultmate XB-NH2-3.5 μm, USA) with a refractive index detector were used for HPLC. Solvent system of double-distilled water-acetonitrile (20:80) was used as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. The temperature of column and refractive index detector were 45 and 40 °C, respectively. The sample quantity was 10 μl each time.

In order to distinguish maltotriose (only α-1,4 bonds) from panose or isopanose (α-1,4 and α-1,6 bonds), the incubation was performed with α-glucosidase in a 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) at 37 °C. This enzyme is capable of hydrolyzing α-1,4 but not α-1,6 linkages in short-chain oligosaccharides.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The GeneBank accession numbers for the Paenibacillus polymyxa Nws-pp2 pulN gene is KJ740392.

Results

Isolation and identification of bacterium

Strain Nws-pp2 was isolated from soil sample of fruit market garbage dump and showed the pullulanase activity when cultivated on the pullulanase screening culture medium. After 48 h growing on the pullulanase screening culture medium plate at 30 °C, significant hydrolysis circle appeared around the bacterial colony (treated with alcohol) (Fig. 1a). The strain was identified as P. polymyxa according to the result of 16S rDNA phylogenetic analysis and the morphology. The 16 s rDNA (1443-bp) displayed the similarity of 99 % to P. polymyxa 1851 (Accession no. EU982546) and P. polymyxa M1 (Accession no. EF656457). The strain was renamed as P. polymyxa Nws-pp2 and deposited at the China Center for Type Culture Collection (http://www.cctcc.org/, Wuhan, China. Accession number: CCTCC AB 2013352).

Cloning of the pulN and gene analysis

Through PCR amplification, a 2532-bp DNA fragment encoding a polypeptide of 843 amino acids was cloned and sequenced. The GenBank accession number of pulN is KJ740392. The G + C content (%) of the pulN is 53.6 %. Homology analysis revealed that PulN in P. polymyxa Nws-pp2 is 88 % identical to the CP002213.1 in P. polymyxa CR1 (hypothetical type I pullulanase), 87 % identical to the CP000154.1 in P. polymyxa E681 and 82 % identical to the CP003107.1 in P. terrae HPL-003. The molecular weight of PulN was estimated to be 95.6 kDa, and the pI value was calculated to be 4.92 by the ExPASy compute pI/Mw program algorithm. Meanwhile, as no report of this pullulanase in previous research, the three-dimensional structure of PulN was predicted by the SWISS-MODEL server and the protein structure was viewed by PdbViewer (Additional file 1: Figure S3).

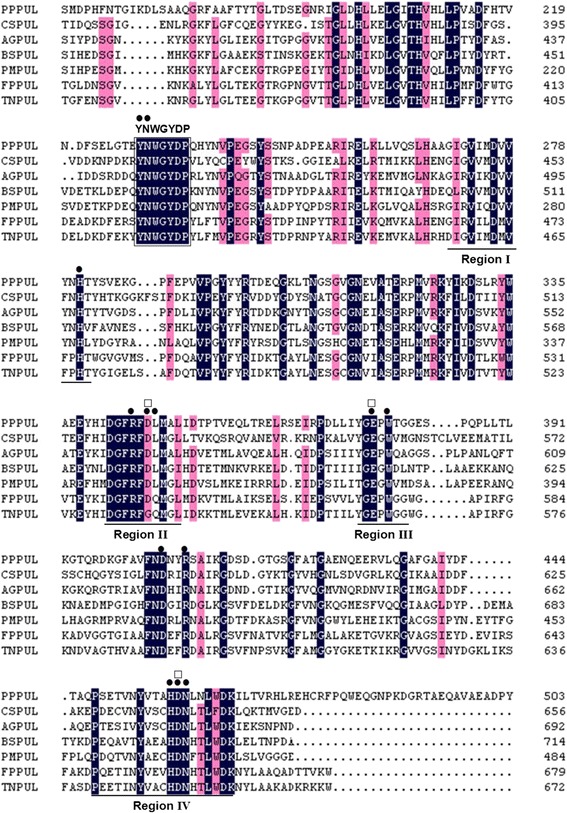

The sequence alignment of the conserved region (PulN) and pullulanase Type I from other different bacterial sources was performed and revealed conservation of aa in regions associated with catalysis and stabilization of the protein, e.g. the active site (Tyr233, Asp234, His281, Arg345, Asp347, Leu348, Glu377, Trp379, Asp405, Arg408, His458, Asp459, Asn460, Asn551, Tyr553), the catalytic site (Asp347, Glu377, and Asp459) and the putative carbohydrate-binding site (Trp759, Trp761, Ile796, Lys805, Asp810).

Compared with the other detail reported type I pullulanase (Table 1), PulN from P. polymyxa Nws-pp2 shows low sequence homology. PulN has the highest amino acid homology (47.6 %) with rPulAg from the Anaerobranca gottschalkii, and 35.5 % homology to the type I pullulanase from Paenibacillus mucilaginosus. Although the overall similarity value is very low, a highly conserved region consisting of seven amino acids (YNWGYDP) is found in all type I pullulanases [6, 16, 22, 23]. This highly conserved seven-residue was detected at the position from 229 to 235 on the N-terminal side of PulN in this study (Fig. 2). Type II pullulanase (with α-1,6 and α-1,4 glycoside activities) gene sequences do not contain this conserved region. This result revealed that PulN belong to a type I pullulanase. Meanwhile, four conserved regions (region I, II, III, IV) that are common to the glycoside hydrolase family enzymes(GH13) were also identified in PulN (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Pairwise similarity between the type I pullulanase amino acid sequences

| Similarity value (%) for pullulanase sequence from: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pullulanase sequence from: | P.polymyxa Nws-pp2 | C.saccharolyticus | A.gottschalkii | Bacillus sp. CICIM 263 | P.mucilaginosus | F.pennavorans Ven5 | T.neapolitana |

| Paenibacillus polymyxa Nws-pp2 | 100 | 37.3 | 47.6 | 38.5 | 41.6 | 39.1 | 38.9 |

| Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus | 100 | 43.2 | 36.8 | 40.0 | 37.3 | 41.1 | |

| Anaerobranca gottschalkii | 100 | 41.3 | 44.4 | 43.8 | 44.4 | ||

| Bacillus sp. CICIM 263 | 100 | 52.7 | 39.8 | 39.6 | |||

| Paenibacillus mucilaginosus | 100 | 41.5 | 42.6 | ||||

| Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5 | 100 | 68.0 | |||||

| Thermotoga neapolitana | 100 | ||||||

The sequences are from the following sources: P. polymyxa Nws-pp2 (this study; GenBank accession no. KJ740392); C. saccharolyticus (GenBank accession no. L39876); A. gottschalkii (GenBank accession no. AY541591); Bacillus sp. CICIM 263 (GenBank accession no. AGA03915); P. mucilaginosus (GenBank accession no. YP004645603); F. pennavorans Ven5 (GenBank accession no. AF096862); T. neapolitana (GenBank accession no. FJ716701)

Fig. 2.

Sequence alignment of the conserved region of PulN and pullulanase Type I from other different bacterial sources. The sequences used in this alignment were obtained from GenBank as following. PPPUL: P. polymyxa pullulanase (this study; GenBank accession no. KJ740392); CSPUL: C. saccharolyticus pullulanase (GenBank accession no. L39876); AGPUL: A. gottschalkii pullulanase (GenBank accession no. AY541591); BSPUL: Bacillus sp. CICIM 263 pullulanase (GenBank accession no. AGA03915); PMPUL: P. mucilaginosus KNP414 pullulanase (GenBank accession no. YP004645603); FPPUL: F. pennavorans Ven5 pullulanase (GenBank accession no. AF096862); TNFUL: T. neapolitana strain KCCM 41025 pullulanase (GenBank accession no. FJ716701). Regions I, II, III, and IV are lined. YNWGYDP conserved in all type I pullulanases is boxed. The numbering refers to the amino acid position in each sequence. The structures are denoted as follows: ●, the active site; □, the catalytic site

Gene expression in E. coli and optimization of the culture conditions

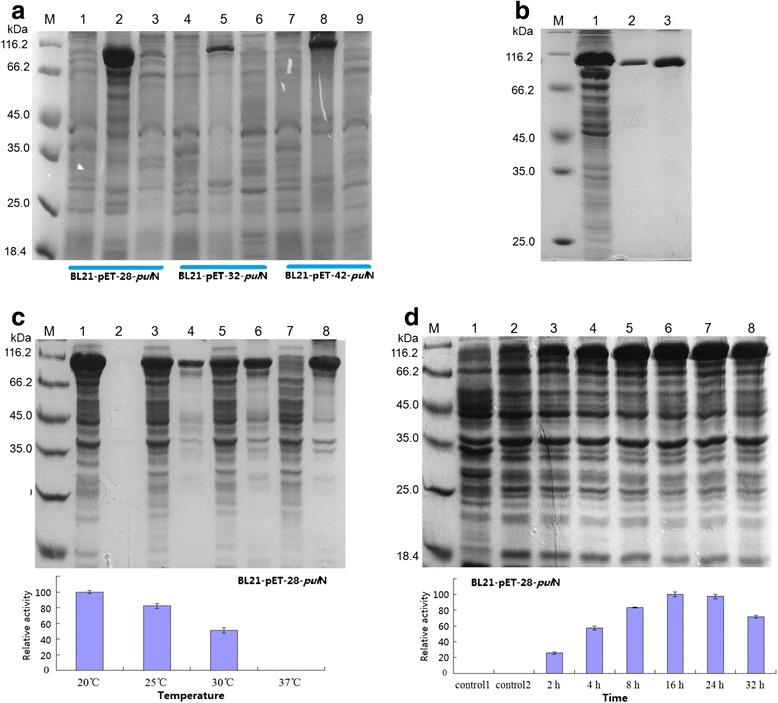

The E. coli expression vectors pET-28a, pET-32a and pET-42a were used to express foreign proteins in this study. The SDS-PAGE profile revealed the presence of an additional protein band in all recombinant strains with an estimated molecular mass of 99 kDa (BL21-pET-28-pulN), 113 kDa (BL21-pET-32-pulN, with 109 aa Trx•Tag protein) and 128 kDa (BL21-pET-42-pulN, with 220 aa GST•Tag protein), which was closed to the molecular mass of PulN. The SDS-PAGE results showed that the recombinant protein appeared mostly as inclusion bodies (induction temperature: 37 °C, induction time 24 h) in recombinant strains BL21-pET-28-pulN/BL21-pET-32-pulN/BL21-pET-42-pulN and no pullulanase activity was detected. Using low temperature induction, the recombinant protein appeared partly as a soluble protein (Fig. 3a). As showing the highest expression level and pullulanase activity, recombinant strain BL21-pET-28-pulN was used to detect the enzymatic properties in the next study.

Fig. 3.

SDS-PAGE of the recombinant protein in E. coli. a SDS-PAGE of recombinant PulN in different pET plasmid (induction temperature: 37 °C, induction time 24 h, IPTG concentration: 0.5 mM). Lane M: protein molecular weight markers; Lane 1: supernatant without inducer (BL21-pET-28-pulN); lane 2-3: precipitation and supernatant; lane 4: supernatant without inducer (BL21-pET-32-pulN); lane 5-6: precipitation and supernatant; lane 7: supernatant without inducer (BL21-pET-42-pulN); lane 8-9: precipitation and supernatant. b SDS-PAGE of the purified PulN. c Recombinant PulN production in BL21-pET-28-pulN with different induction temperatures (IPTG concentration: 0.1 mM, induction time 24 h). lane 1-2: supernatant and precipitation at 20 °C; lane 3-4: supernatant and precipitation at at 25 °C; lane 5-6: supernatant and precipitation at 30 °C; lane 7-8: supernatant and precipitation at at 37 °C. The histogram shows the comparison of pullulanase activity at different induction temperature. d Recombinant PulN production in BL21-pET-28-pulN with different induction time (IPTG concentration: 0.1 mM, induction temperature 20 °C). lane 1: supernatant of empty vector, lane 2: supernatant of BL21-pET-28-pulN without inducer; lane 3-8: supernatant of recombination strain after 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 16 h, 24 h, 32 h induction (BL21-pET-28-pulN). The histogram shows the comparison of pullulanase activity after different induction time

The optimization of PulN (BL21-pET-28-pulN) expression conditions was concerned using the single-factor experiments method. As shown in Fig. 3c, high induction temperature had a negative effect on the production of soluble recombinant protein. When the induction temperatures was 25 °C or above (Fig. 3c, line 3-8), the content of soluble protein existed in supernatant declined gradually (Fig. 3c, line 3, 5 and 7). Meanwhile, inclusion bodies (lack of proper folding) existed in precipitate increased (Fig. 3c, line 4, 6 and 8). Meanwhile, enzyme activity decreased when induction temperature increased, and no pullulanase activity can be detected when the temperature up to 37 °C, especially. These results suggested that low culture temperature facilitated proper folding of the protein and 20 °C was regarded as the optimal temperature for the production of the recombinant PulN. Fermentation time was another remarkable parameter that affected the production of PulN. As shown in Fig. 3d, the expressed protein PulN increased with the extension of the culture time within a certain range (Fig. 3d, line 3-6). Also, the pullulanase activity was increased with the recombinant protein expression level. However, when cells were fermented for more than 16 h, there was no more significant accumulating of the recombinant protein (Fig. 3d, line 7 and 8). So we chose 16 h as the culture time to collect recombinant strains (BL21-pET-28-pulN). The E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring pET28a empty plasmids and recombinant strains without IPTG induction were fermented in same condition as controls (Fig. 3d, line 1 and 2). No pullulanase activity was detected in uninduced transformant or from transformant harboring the empty pET plasmid. The influence of IPTG concentration (from 0.1 to 1.0 mM) and the shaking speed (150, 180, 200 and 230 rpm) on the target protein distribution were negligible. However, pullulanase activity decreased remarkable when IPTG concentration was above 1.0 mM (data not shown). The optimal expression conditions were detected with 0.1 mM IPTG, 20 °C for induction temperature and induction time for 16 h in our research. The recombinant pullulanase (PulN) reached about 0.34 mg/ml (about 20 % of total protein). The optimal enzyme activities of recombinant PulN was 6.49 U/ml.

Purification and quantitative assay of recombinant PulN by SDS-PAGE analysis

The recombinant pullulanase (PulN from strain BL21-pET-28-pulN) was overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells under the optimal conditions and was purified by Ni-NTA purification procedures (Fig. 3). The BL21-pET-28-pulN construct contained His-tag in order to facilitate Ni-NTA purification. About 10.6 mg PulN which was purified up to 4.28 times with a recovery of 58.7 % was obtained using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Table 2). The crude extract enzyme specific activity was 3.78 U/mg, and specific activity was up to 16.17 U/mg after purification. The purified enzyme migrated on SDS-PAGE as a single band with an apparent molecular mass of about 99.0 kDa (Fig. 3b). There was no obvious bands of impurity protein appeared after being concentrated five times (Fig. 3b). The results indicated that Ni-NTA affinity chromatography was an appropriate method for the protein purification (Table 2).

Table 2.

Purification of PulN by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography

| Purification step | Total activity (U) | Total protein (mg) | Specific activity (U/mg) | Yield (%) | Purification fold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 292.05 | 77.26 | 3.78 | 100.00 | 1.00 |

| Ni-NTA | 171.41 | 10.60 | 16.17 | 58.7 | 4.28 |

The crude enzyme was obtained from 45 ml culture and 10 ml purified enzyme was obtained.

Biochemical characterization of the purified recombinant pullulanase

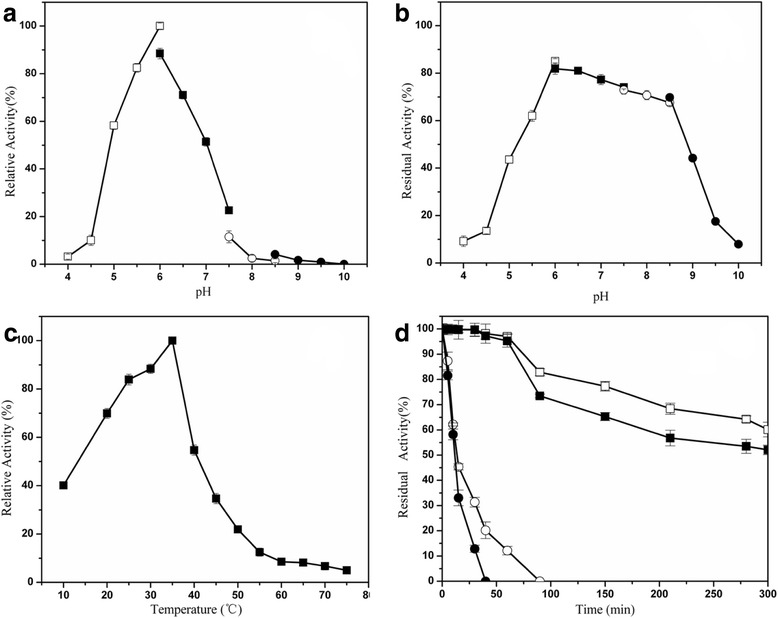

The activities of pullulanase at various pH values and temperatures were measured by using pullulan as the substrate. The purified PulN exhibited a higher enzyme activities over a pH range of 5.0–6.5, and the highest specific enzyme activity was detected at pH 6.0 (Fig. 4a). The enzyme retained more than 62 % of the maximal activity after incubation in pH 5.5–8.5 for 90 min (Fig. 4b). The optimal temperature of purified PulN was 35 °C, and there was still 40 % of the maximal activity at only 10 °C (Fig. 4c). PulN retained more than 61 % of the initial activity after incubation at 35 °C for 300 min, and more than 52 % of the initial activity after incubation at 40 °C for 300 min, exhibiting a remarkable stability. However, the activity decreased sharply when the temperature is over 45 °C, it was completely inactivated at 45 °C for 90 min and at 50 °C for 40 min, respectively (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Characterization of recombinant PulN. a Effect of pH on PulN activity at 35 °C in buffers ranging from pH 4.0-10.0. b Effect of pH on the stability of PulN activity. After incubation at 35 °C for 90 min in buffers ranging from pH 4.0-10.0 and the residual activity was measured at pH 6.0. c Effect of temperature on PulN activity assayed at pH 6.0. d Thermostability of PulN. The enzyme was preincubated at 35 °C (□), 40 °C (■), 45 °C (○), 50 °C (●) at pH 6.0. After various time intervals, samples were withdrawn and the residual activity was measured at 35 °C. The statistical tool Origin 8.0 was used to analyze the enzymatic properties data. Each value represents the mean ± SD of triplicate

The effects of different metal ions and chemical reagents on the enzyme were examined in pH 6.0 citrate buffer at 35 °C for 15 min (Tables 3 and 4). At low concentration (1 mM), Ca2+, Zn2+, Ni2+ partly inhibited or had no effects on the enzyme, while Mn2+, Co2+could slightly enhanced the enzyme activity. However, at high concentration (5 and 10 mM), Zn2+ and Fe2+ showed significantly inhibited effects, reducing the activity to 83.8, 49.3, 58.3 and 42.0 % of the control samples, respectively. In comparison, Mg2+ could slightly enhance the enzyme activity. Cu2+ showed significantly inhibited effects and only 2.9 % pullulanase activity was detected within 10 mM Cu2+. The pullulanase activities are not significantly affected by 5 mM EDTA, indicating that metal ions were not required for enzyme activity. The enzyme was unstable during incubation at 35 °C for 15 min in the presence of surfactants such as 2 and 4 M urea and 1 % SDS, which led to significant loss of activity. Enzyme activity was enhanced by the addition of reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT) and 2-mercaptoethanol, and was inhibited by α-cyclodextrins, which is known as possible competitive inhibitors of this enzyme [16].

Table 3.

Effects of metal ions and chemical reagents on the PulN activity

| Metal ions compounds | Relative activity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 mM | 5 mM | 10 mM | |

| None | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| MgCl2 | 104.1 ± 1.4 | 109.0 ± 0.2 | 117.0 ± 0.5 |

| CaCl2 | 97.9 ± 2.0 | 97.4 ± 1.6 | 96.0 ± 1.6 |

| CuCl2 | 75.1 ± 2.5 | 11.9 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| ZnSO4 | 97.6 ± 0.7 | 83.8 ± 0.7 | 49.3 ± 1.4 |

| NiSO4 | 99.0 ± 2.3 | 103.1 ± 0.2 | 102.1 ± 0.9 |

| MnCl2 | 114.8 ± 2.0 | 154.8 ± 2.7 | 215.2 ± 4.8 |

| CoCl2 | 121.7 ± 0.7 | 124.2 ± 1.1 | 125.1 ± 0.9 |

| FeSO4 | 77.2 ± 3.4 | 58.3 ± 0.9 | 42.0 ± 1.1 |

The data represent the mean of three experimental repeats with SD of ≤ 5 %

Table 4.

Effects of metal ions and chemical reagents on the PulN activity

| Reagents | Concentration | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| None | - | 100 |

| EDTA | 5 mM | 102.1 ± 0.2 |

| SDS | 1 mM | 12.3 ± 0.8 |

| TritonX-100 | 0.1 % | 99.8 ± 1.1 |

| 1 % | 99.4 ± 0.2 | |

| Urea | 2 M | 71.2 ± 0.4 |

| 4 M | 34.8 ± 2.3 | |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | 5 mM | 132.7 ± 1.9 |

| 10 mM | 167.3 ± 4.0 | |

| DTT | 10 mM | 154.4 ± 1.5 |

| α-cyclodextrin | 0.1 % | 77.8 ± 0.8 |

The data represent the mean of three experimental repeats with SD of ≤ 5 %

The kinetics (Vmax and Km) of the purified pullulanase was determined by Lineweaver-Burk double reciprocal plot at varying substrate (pullulan) concentration. The Km of the enzyme with pullulan as substrate was 15.25 mg/ml, and the Vmax was 20.1 U/mg.

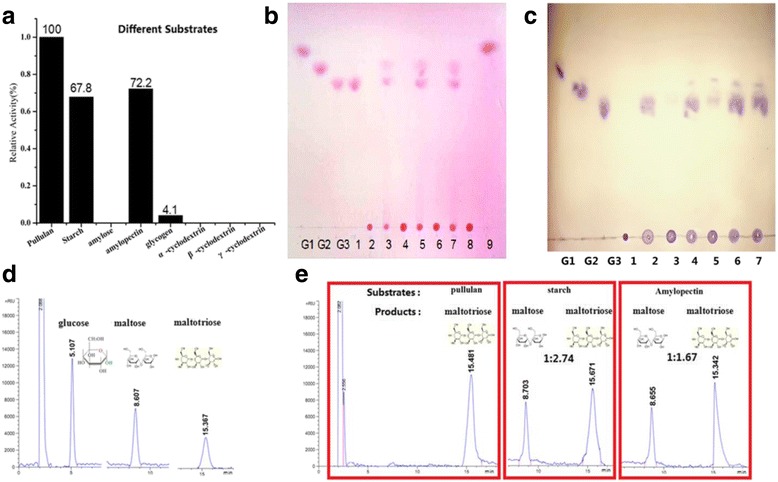

Substrate specificity and analysis of hydrolyzates

The ability of PulN to hydrolyze various α-glucans as well as pullulan was determined by using various substrates at concentrations of 1 % (w/v). The activity of hydrolyzing pullulan, amylopectin, starch and glycogen ]were 16.17 U/mg, 11.67 U/mg, 10.96 U/mg and 0.65 U/mg, respectively. No activity was detected with amylose and cyclodextrin as substrate. PulN can hydrolyze pullulan, soluble starch, amylopectin, glycogen, all of which have α-1,6 glycosidic linkages in their structures (Fig. 5a). In comparison, PulN cannot hydrolyze amylose, which only consist of α-1,4 glycosidic linkage.

Fig. 5.

Substrate specificity and analysis of hydrolyzed products. a Relative activity on different substrates. b TLC analysis of hydrolysis products with various substrates. Lane G1: glucose; lane G2: maltose; lane G3: maltotriose; lane 1: pullulan with PulN; lane 2: pullulan; lane 3: starch with PulN; lane 4: starch; lane 5: amylopectin with PulN; lane 6: amylopectin; lane 7: glycogen with PulN; lane 8: glycogen; lane 9: products of pullulan with α-glucosidase. c TLC analysis of hydrolysis products compared with the industrial enzyme at different temperature. Lane G1: glucose; lane G2: maltose; lane G3: maltotriose; lane 1: pullulan; lane 2: pullulan with PulN at 0 °C; lane 3: pullulan with Promozyme at 0 °C; lane 4: pullulan with PulN at 20 °C; lane 5: pullulan with Promozyme at 20 °C; lane 6: pullulan with PulN at 40 °C; lane 7: pullulan with Promozyme at 40 °C. d HPLC analysis of standard (glucose, maltose, maltotriose). e HPLC analysis of hydrolysates from with various substrates (pullulan, soluble starch and amylopectin)

The hydrolyzates of enzyme substrate reaction were detected by TLC and HPLC using standard sugar solutions (glucose, maltose, maltotriose) (Fig. 5b,d). After incubation of this enzyme with pullulan, the hydrolytic pattern revealed the complete conversion of pullulan to maltotriose in an endo-acting fashion. The hydrolyzed product of pullulan was subsequently incubated with bacteria α-glucosidase, which specifically hydrolyzes α-1,4 glycosidic linkages. A complete conversion into glucose verified that the hydrolyzed product from pullulan was maltotriose, not panose or isopanose (possessing α-1,4 and α-1,6 glycosidic linkages). The results indicated that pullulan (contain only α-1,6 linkages) was completely converted to maltotriose (Fig. 5b,d). As to soluble starch and amylopectin, the major hydrolysis products were maltotriose and maltose (The molar ratio of maltotriose: maltose was 2.74:1 and 1.67:1, respectively) (Fig. 5e). According to these results, PulN specifically attacks α-1,6 linkages of branched oligosaccharides and can therefore be classified as a type I pullulanase. Meanwhile, the results (pullulan hydrolytic reactions with the industrial enzyme as a control at different temperature) revealed that cold-adapted pullulanase (PulN) shows the better property (hydrolytic activity) under low temperature (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

Pullulanase, an important debranching enzyme, has been widely utilized to hydrolyse the α-1,6 glucosidic linkages in starch/sugar industry and used predominantly in conjunction with other enzymes that break down starch [1]. Selecting new bacterial strains or improving bacterial strains is a prerequisite and effective solution in industrial applications and will be important for maximal production in order to get better yield in starch industry [5, 6]. Although P. polymyxa strains are well known for their ability to secrete a large number of useful extracellular enzymes, there is no report of P. polymyxa type I pullulanase gene and the recombinant strain. Type I pullulanase is an enzyme that specifically hydrolyses α-1,6 glycosidic linkages in pullulan or branched oligosaccharides to produce maltotriose and linear oligosacharides [6]. Most of type I pullulanase have been investigated exhibit thermophilic or mesophilic properties. There are just few reports of cold-adapted pullulanases. In a previous study, a pullulanase, Pul-SH3, (about 70 kDa) purified from the optimized culture of a wild strain Exiguobacterium sp. SH3 showed high catalytic activity at ambient temperature and seemed to exhibit outstanding cold-adapted characteristics [8]. However, the gene of the enzyme was not obtained and the enzymatic properties were not characterized further. In this paper, the novel cold-adapted type I pullulanase from P. polymyxa was obtained and expressed in E. coli. The enzyme activity reached 6.49 U/ml after a series of induction optimization. Also, biochemical characterization and substrate specificity of the purified recombinant enzyme were detail described.

Amylolytic enzymes have different catalytic pro perties and structures. However, as containing similar substrates and modes of action, strong similarities exist in their amino acid sequences between substrate binding sites and catalytic sites. BLASTP analysis of the amino acid sequence derived from the P. polymyxa pullulanase (PulN) revealed the YNWGYDP motif which is known to be involved in the hydrolysis of α-1,6 bonds in pullulan and the four conserved regions (regions I, II, III, and IV) that are typical of glycosyl hydrolase family (GHF) 13 α-amylases. These regions contribute to the active site architecture within the catalytic domain of GHF 13 enzymes and encompass the catalytic triad of acidic residues, namely Asp347, Glu377, and Asp459 in the P. polymyxa pullulanase (Additional file 1: Figure S3b). The pattern of pullulanase action against pullulanase substrates differs from that for α-amylases, indicating that other amino acids in addition to the three residues mentioned above are involved in catalysis. Tyr233 and Trp231, located in the pullulanase sequence YNWGYDP, are important for van der Waals interactions with glucose residues in subsites -1 and -2 [15]. Moreover, the histidine (His) residues, which have been found to participate specifically in catalysis of α-1,6 glycosidic linkages by Klebsiella aerogenes pullulanase [24], are also present in P. polymyxa pullulanase in regions I and IV at positions His498 and His676, respectively.

As showing the highest expression level and pullulanase activity, recombinant strain BL21-pET-28-pulN was used to express foreign proteins and detect the enzymatic properties in this study. In this work, some culture conditions affected enzyme activity significantly. The optimal expression conditions were detected with 0.1 mM IPTG, 20 °C for induction temperature and induction time for 16 h in our research. High temperature (25, 30, 37 °C) and/or high IPTG concentration (>1.0 mM) resulted in activity decreasing. In this study, pullulanase gene (pulN) was functionally expressed in E. coli through expression vector replacement and induction expression strategy optimization. Another impressive fact is that through the optimization of expression, most of the inclusion bodies (with no pullulanase activity, 37 °C) were transformed to soluble protein (functional expression, 20 °C) distinctly (Fig. 3).

This study provided the detailed PulN enzymatic properties and the worth concern was the low temperature catalytic performance (similar with enzymes from psychrophilic bacteria, but cloned from the mesophilic strain). As we known, most of type I pullulanase shows thermophilic or mesophilic properties (Table 5) and the enzyme activity of most thermophilic/mesophilic pullulanases decline dramatically in lower temperatures (below their optimum temperature). A more comprehensive knowledge on the structure and function of the cold-adapted amylopullulanase from Exiguobacterium sp. SH3 set the stage for development of customdesigned biocatalysts that are efficient at ambient temperatures [8]. Addition of a novel cold-adapted glycogen branching enzyme from Rhizomucor miehei to wheat bread increased its specific volume and had an antistaling effect in comparison with the control [25]. However, there was few report of cold-adapted pullulanases (wild strain) [26] and no report of cold-adapted pullulanase produced from recombinant strain with detailed enzymatic properties (Table 5). In this research, purified pullulanase had an optimal temperature at 35 °C which was similar to that from Exiguobacterium sp. SH3 (30 °C) [8] and much lower than that from Bacillus acidopullulyticus (60 °C) [26], Anaerobranca gottschalkii (70 °C) [12], Thermotoga neapolitana (80 °C) [15] and Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5 (80 °C) [16]. Both pullulanase from Exiguobacterium sp. SH3 and PulN in this study has a 40 % residual activity when temperature is only 10 °C, exhibiting a good low temperature catalytic performance. The purified PulN was sensitive to high temperature, and it was inactivated within 40 min in 50 °C and 10 min in 60 °C. The thermal stability of PulN is much poorer than those from thermophilic microorganisms. Purified PulN had an optimal pH of 6.0 in citrate buffer. Similarly, optimal pH 6.0 was also observed from Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5 [16], Bacillus sp. AN-7 [27] and Bacillus stearothermophilus [28]. Pullulanase from other strains showed different optimal pH. The optimal pH of pullulanase was pH 4.5 from Bacillus acidopullulyticus [26], pH 6.5 from Bacillus sp. CICIM 263 [14], and pH 8.0 from Anaerobranca gottschalkii [12]. The best pH condition for starch saccharification is 4.5 to 5.5, and that is why pullulanase from Bacillus acidopullulyticus (Promozyme; Novozymes A/S) was wildly used. The purified PulN was stable after incubated for 90 min in pH condition from 5.5 to 8.5. The results indicated that although the activity of PulN in alkaline environment is low (55–6 % of the maximum activity), it has a considerable stability in alkaline environment. Mn2+, Co2+ could enhance the enzyme activity, but Zn2+, Fe2+ and Cu2+ inhibited the enzyme activity, just like pullulanase from Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5 [16]. Ca2+ was not inhibitory and was agreement with the pullulanase primary structure of PulN lacks typical Ca2+ binding residues found in other members of glycoside hydrolase family 13 [12]. In our research, the recombinant PulN activities are not significantly affected by 5 mM EDTA, and this results may indicated that divalent cation was not necessary in recombinant PulN. The enzymatic properties (unaffected by EDTA) was also approved by the pullulanase in Anaerobranca gottschalkii (EDTA was not inhibitory even at high concentrations 0.5 M) [12]. Reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT) and 2-mercaptoethanol cause a significant activation of the cloned pullulanase (PulN). It is likely that DTT inhibits the oligomerization of the enzyme (leading to its inactivation) by reducing the disulfide linkage between enzyme monomers.

Table 5.

The catalytic activity comparison with different temperature

| Enzyme | Strain and reference | optimum temperature (°C) | Relative activity at a range of temperature (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | |||

| PulN | Paenibacillus polymyxa Nws-pp2 (this study) | 35 | 40 | 70 | 85 | 55 | <20 | — | — |

| Pul-SH3 | Exiguobacterium sp. SH3 [8] | 30 | 45 | 80 | 100 | 70 | <40 | — | — |

| rPulAs | Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5 [16] | 80 | — | — | <10 | 20 | 35 | 50 | 80 |

| rPulAg | Anaerobranca gottschalkii [12] | 70 | — | — | — | <30 | 55 | 85 | 100 |

| pulullanase | Bacillus sp. AN-7 [27] | 90 | — | — | — | <25 | 50 | 65 | 80 |

| pulullanase | Bacillus stearothermophilus [28] | 65 | — | <10 | 25 | 45 | 70 | 95 | 10 |

| PulA1 | Bacillus sp. CICIM 263 [14] | 70 | — | — | <40 | 50 | 60 | 80 | 100 |

The pullulanase from P. polymyxa Nws-pp2 preferentially hydrolyzed pullulan (Fig. 5) and other carbohydrates containing α-1,6 glycosidic linkages, including amylopectin (72.2 % activity relative to the pullulan-cleaving activity) (Fig. 5), soluble starch (67.8 %), and glycogen (4 %), while amylose was not significantly hydrolyzed. The substrate and product profiles (analysis by TLC and HPLC) indicate that PulN specifically attacks α-1,6 linkages of branched oligosaccharides and therefore can be classified as a type I pullulanase. Therefore, the pullulanase from P. polymyxa Nws-pp2 is the novel cold-adapted type I pullulanase from Paenibacillus sp. that has been described.

Conclusions

In this study, we obtained a novel pullulanase gene from the strain P. polymyxa Nws-pp2 and the gene was functional expressed in E. coli through expression vector replacement and induction expression strategy optimization. This is the novel report of the type I pullulanase in Paenibacillus polymyxa (including wild strain and recombinant strain) and heterologous expression with the detailed enzymatic properties. Also, the novel cold-adapted pullulanase provide the potential value in food industry applications. Future investigations will focus on the application of this enzyme in the food industry and studies on structure-function relationships.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (No. 2013AA102109, NO. 2012AA022206), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. C050203-31200596, 31570795), the National Major Science and Technology Projects of China (No. 2012ZX09304009) and the National Basic Research Program of China (973, Program No. 2012CB721103).

Abbreviations

- pulN

the pullulanase gene from Paenibacillus polymyxa Nws-pp2

- PulN

the pullulanase from Paenibacillus polymyxa Nws-pp2

- LB

Luria Bertani medium

- kan

Kanamycin

- amp

Ampicillin

- IPTG

Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- GHF

Glycosyl hydrolase family

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- EDTA

Ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid

- TLC

Thin layer chromatography

- HPLC

High performance liquid chromatography

- CCTCC

China Center for Type Culture Collection

- DNS

3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid reagent

Additional file

Section A: The schematic representation of type I pullulanase. Section B: The bacterial strains, plasmids, chemicals and culture conditions. Section C: Pullulanase gene manipulation/propagation. Section D: The three-dimensional structure of PulN. Section E: The purification of recombinant protein. Section F: The Lineweaver-Burk plot. (DOC 556 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

WW participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. JM participated in the gene cloning and expression of this novel cold-tolerant type I pullulanase from the strain Paenibacillus polymyxa Nws-pp2. S-Q C performed the wild strain screening and the enzyme characterizations research including the enzyme activity/stability, optimum temperature and optimum pH. X-H C performed in substrate specificity and hydrolysates products analysis. D-Z W coordinated the conception and design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Wei Wei, Phone: 86-21-64251803, Email: lyuwei-1982@hotmail.com.

Dong-Zhi Wei, Email: dzhwei@ecust.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Henrissat B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on aminoacidsequence similarities. Biochem J. 1991;280:309–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svensson B. Protein engineering in the α-amylase family: catalytic mechanism, substrate specificity, and stability. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:141–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00023233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hii SL, Tau CL, Rosfarizan M, Ariff AB. Characterization of Pullulanase Type II from Bacillus cereus H1.5. Am J Biochem Biotech. 2009;5:170–179. doi: 10.3844/ajbbsp.2009.170.179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Shishtawy RM, Mohamed SA, Asiri AM, Gomaa AB, Ibrahim IH, Al-Talhi HA. Solid fermentation of wheat bran for hydrolytic enzymes production and saccharification content by a local isolate Bacillus megatherium. BMC Biotechnol. 2014;24:14–29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-14-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kłosowski G, Mikulski D, Czupryński B, Kotarska K. Characterisation of fermentation of high-gravity maize mashes with the application of pullulanase, proteolytic enzymes and enzymes degrading non-starch polysaccharides. J Biosci Bioeng. 2010;5:466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doman-Pytka M, Bardowski J. Pullulan degrading enzymes of bacterial origin. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2004;30:107–121. doi: 10.1080/10408410490435115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duffner F, Bertoldo C, Andersen JT, Wagner K, Antranikian G. A new thermoactive pullulanase from Desulfurococcus mucosus: cloning, sequencing, purification, and characterization of the recombinant enzyme after expression in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6331–6338. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.22.6331-6338.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajaei S, Heidari R, Shahbani Zahiri H, Sharifzadeh S, Torktaz I, Akbari Noghabi K. A novel cold-adapted pullulanase from Exiguobacterium sp. SH3: Production optimization, purification, and characterization. Starch-Starke. 2014;66:225–234. doi: 10.1002/star.201300030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim CH, Choi HI, Lee DS. Pullulanases of alkaline and broad pH range from a newly isolated alkalophilic Bacillus sp. S-1 and a Micrococcus sp. Y-1. J Ind Microbial Biot. 1993;12:48–57. doi: 10.1007/BF01570128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki Y, Hatagaki K, Oda H. A hyperthermostable pullulanase produced by an extreme thermophile, Bacillus flavocaldarius KP 1228, and evidence for the proline theory of increasing protein thermostability. Appl Microbial Biot. 1991;34:707–714. doi: 10.1007/BF00169338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben Messaoud E, Ben Ammar Y, Mellouli L, Bejar S. Thermostable pullulanase type I from new isolated Bacillus thermoleovorans US105: cloning, sequencing and expression of the gene in E. coli. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2002;31:827–832. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(02)00185-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertoldo C, Armbrecht M, Becker F, Schäfer T, Antranikian G, Liebl W. Cloning, sequencing, and characterization of a heat-and alkali-stable type I pullulanase from Anaerobranca gottschalkii. Appl Environ Microb. 2004;70:3407–3416. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3407-3416.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albertson GD, McHale RH, Gibbs MD, Bergquist PL. Cloning and sequence of a type I pullulanase from an extremely thermophilic anaerobic bacterium, Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. BBA-Gene Struct Expr. 1997;1354:35–39. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(97)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Zhang L, Niu D, Wang Z, Shi G. Cloning, expression, characterization, and biocatalytic investigation of a novel bacilli thermostable type I pullulanase from Bacillus sp. CICIM 263. J Agr Food Chem. 2012;60:11164–11172. doi: 10.1021/jf303109u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang J, Park KM, Choi KH, Park CS, Kim GE, Kim D, et al. Molecular cloning and biochemical characterization of a heat-stable type I pullulanase from Thermotoga neapolitana. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2011;48:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertoldo C, Duffner F, Jorgensen PL, Antranikian G. Pullulanase type I from Fervidobacterium pennavorans Ven5: cloning, sequencing, and expression of the gene and biochemical characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2084–2091. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.2084-2091.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trincone A. Marine biocatalysts: enzymatic features and applications. Mar Drugs. 2011;9:478–499. doi: 10.3390/md9040478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lal S, Tabacchioni S. Ecology and biotechnological potential of Paenibacillus polymyxa: a minireview. Indian J Microbiol. 2009;49:2–10. doi: 10.1007/s12088-009-0008-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang SH, Yang Y, Zhang J, Sun J, Matsukawa S, Xie JL, et al. Characterization of abnZ2 (yxiA1) and abnZ3 (yxiA3) in Paenibacillus polymyxa, encoding two novel endo-1,5-α-l-arabinanases. Bioresources Bioprocessing. 2014;1:14. doi: 10.1186/s40643-014-0014-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castro GR, Santopietro LMD, Sineriz F. Acid pullulanase from Bacillus polymyxa MIR-23. Appl Biochem Biotech. 1993;37:227–233. doi: 10.1007/BF02788874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HJ, Park JN, Kim HO, Shin DJ, Chin JE, Lee HHB, et al. Cloning and expression of a Paenibacillus sp neopullulanase gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae producing Schwanniomyces occidentalis glucoamylase. J Microbiol Biotechn. 2002;12:340–344. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai XH, Ma J, Wei DZ, Lin JP, Wei W. Functional expression of a novel alkaline-adapted lipase of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens from stinky tofu brine and development of immobilized enzyme for biodiesel production. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;106:1049–1060. doi: 10.1007/s10482-014-0274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei W, Ma J, Guo S, Wei DZ. A type I pullulanase of Bacillus cereus Nws-bc5 screening from stinkytofu brine: Functional expression in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis and enzyme characterization. Process Biochem. 2014;49:1893–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2014.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamashita M, Matsumoto D, Murooka Y. Amino acid residues specific for the catalytic action towards α-1,6-glucosidic linkages in Klebsiella pullulanase. J Ferment Bioeng. 1997;84:283–290. doi: 10.1016/S0922-338X(97)89246-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu S, Liu Y, Yan Q, Jiang ZQ. Gene cloning, functional expression and characterisation of a novel glycogen branching enzyme from Rhizomucor miehei and its application in wheat breadmaking. Food Chem. 2014;159:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.02.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kusano S, Shiraishi T, Takahashi SI, Fujimoto D, Sakano Y. Immobilization of Bacillus acidopullulyticus pullulanase and properties of the immobilized pullulanases. J Ferment Bioeng. 1989;68:233–237. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(89)90021-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunamneni A, Singh S. Improved high thermal stability of pullulanase from a newly isolated thermophilic Bacillus sp. AN-7. Enzyme Microb Tech. 2006;39:1399–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuriki T, Park JH, Imanaka T. Characteristics of thermostable pullulanase from Bacillus stearothermophilus and the nucleotide sequence of the gene. J Ferment Bioeng. 1990;69:204–210. doi: 10.1016/0922-338X(90)90213-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]