Abstract

Purpose

Because ovarian granulosa cells are essential for oocyte survival, we examined three human granulosa cell lines as models to evaluate the ability of the pan-caspase inhibitor benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethyl ketone (Z-VAD-FMK) to prevent primordial follicle loss after ovarian tissue transplantation.

Methods

To validate the efficacy of Z-VAD-FMK, three human granulosa cell lines (GC1a, HGL5, COV434) were treated for 48 h with etoposide (50 μg/ml) and/or Z-VAD-FMK (50 μM) under normoxic conditions. To mimic the ischemic phase that occurs after ovarian fragment transplantation, cells were cultured without serum under hypoxia (1 % O2) and treated with Z-VAD-FMK. The metabolic activity of the cells was evaluated by WST-1 assay. Cell viability was determined by FACS analyses. The expression of apoptosis-related molecules was assessed by RT-qPCR and Western blot analyses.

Results

Our assessment of metabolic activity and FACS analyses in the normoxic experiments indicate that Z-VAD-FMK protects granulosa cells from etoposide-induced cell death. When cells are exposed to hypoxia and serum starvation, their metabolic activity is reduced. However, Z-VAD-FMK does not provide a protective effect. In the hypoxic experiments, the number of viable cells was not modulated, and we did not observe any modifications in the expressions of apoptosis-related molecules (p53, Bax, Bcl-xl, and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)).

Conclusion

The death of granulosa cell lines was not induced in our ischemic model. Therefore, a protective effect of Z-VAD-FMK in vitro for further use in ovarian tissue transplantation could not be directly confirmed. It will be of interest to potentially use Z-VAD-FMK in vivo in xenograft models.

Keywords: Ovarian granulosa cells, Z-VAD-FMK, Etoposide, Hypoxia, Ovarian transplantation, Fertility preservation

Introduction

In the last decade, the removal, cryopreservation, and subsequent grafting of ovarian strips after cancer treatment has been successfully used to re-establish female fertility. To date, more than 40 live births after using this technique have been reported worldwide. However, the pregnancy rate after the autografting of frozen-thawed ovarian tissue is approximately 30 % [1, 2]. The absence of vascular anastomoses between host and grafted tissues is responsible for post-transplantation ischemic injuries that jeopardize long-term fecundity. The primordial follicle pool in ovarian tissue represents the ovarian reserve and is closely correlated with the life span of the graft. Previous studies have demonstrated a major primordial follicular loss after grafting rather than after the freeze/thaw step [3–5]. Multiple researches have attempted to determine the primary reason for accelerated follicular loss after transplantation. Several explanations that have been identified include fibrosis [6], ischemia [4, 5], the production of reactive oxygen species [7], and, more recently, follicular activation after disruption of the Hippo signaling pathway and the activation of the PI3K-PTEN-AKT-FOXO3 pathway following transplantation [8, 9]. Grafting studies have also indicated an apoptosis of the follicles shortly after transplantation, which leads to a 50 to 80 % depletion of the initial pool of primordial follicles [10, 11].

In the ovary, the layer of granulosa cells surrounding the oocyte plays an essential role in its development and maturation [12]. Therefore, rescuing granulosa cells from death is crucial to favor follicular survival. Moreover, in a previous study, granulosa cells, more so than oocytes, were identified as the main cells affected by the freeze/thaw processing of ovarian tissue [13]. Granulosa cells seem to be able to respond to hypoxia by increasing their synthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [14], which is an important angiogenic factor that could reduce the hypoxic period post-transplantation, as previously shown in ovarian grafting studies [11, 15–20]. Because of the restricted availability and relatively short life span of primary cultures of granulosa cells, human granulosa cell lines were developed to facilitate research [21].

As a consequence of exposure to stressors, apoptotic responses can be activated within follicles and granulosa cells. Apoptosis is a physiological “self-killing” process crucial for the maintenance of tissue homeostasis during development, and the disruption of the apoptotic pathway is involved in numerous pathologies [22]. The caspase family of cysteine proteases is a key regulator of the apoptotic pathway within the ovary. Their activation leads to the cleavage of a specific subset of cellular polypeptides and the modification of expression of Bcl-2 family members. Bcl-2 protein family members can be pro- or anti-apoptotic, such as Bax or Bcl-xl, respectively. At the end of the apoptotic signaling cascade, one of the main targets of caspase-3, the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), is cleaved. Similarly, p53 is involved in the detection of cellular damage, and its activation induces the expression of target genes leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [23, 24]. Together, these molecules serve as important markers of cells undergoing apoptosis.

To improve follicular preservation after transplantation, anti-apoptotic molecules were tested in different models. In the field of fertility preservation, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and its agonists are largely studied for their combined anti-apoptotic and pro-angiogenic properties. While the ability of S1P to protect follicles from chemotherapy and radiation-induced damages has been well demonstrated [25–29], the protective effects of S1P in cryopreserved tissue grafting studies remain controversial [30–33]. Another alternative, a permeable synthetic peptide pan-caspase inhibitor, benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethyl ketone (Z-VAD-FMK), has only been studied once in a xenograft model of cryopreserved ovarian tissue after producing encouraging results as a therapeutic option [34]. Z-VAD-FMK has also been identified as an efficient caspase inhibitor to prevent ischemia/reperfusion injuries in the liver [35], brain [36], and pancreas [37]. Moreover, successful cryopreservation and recovery of cells were obtained using Z-VAD-FMK as a cryoprotective agent [38]. Collectively, these results indicate the potential suitability of Z-VAD-FMK to improve ovarian tissue cryopreservation and the recovery rate of transplanted tissue.

In this study, our aim was to determine whether human granulosa cell lines could be protected by Z-VAD-FMK from induced cell death in vitro. Our experiments were performed on three human granulosa-derived cell lines displaying different morphologies and properties (GC1a, HGL5, and COV434) [21]. Two of them were generated from human luteinized granulosa cells isolated from follicular fluids and further immortalized through oncogenic transformation (with SV40 large T antigen for GC1a [39, 40] or with HPV 16 for HGL5 [41]). The COV434 cell line was derived from a metastatic granulosa cell tumor [42].

In a more global context, we hypothesize that a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor, such as Z-VAD-FMK, could act to prevent apoptosis in transplanted ovarian tissue.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

The GC1a cell line was provided by Dr. Takashi Ohba (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Kumamoto University School of Medicine, Kumamoto, Japan), and the HGL5 cell line was a gift from Dr. Bruce Carr (Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA). We purchased the COV434 human granulosa cell line from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECACC cat. No. 07071909, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). GC1a and HGL5 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F-12 and COV434 cells in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with GlutaMAX (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), supplemented with 10 % heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The cell culture was maintained in a traditional humidified incubator supplied with room air (20 % oxygen and 75 % nitrogen) buffered with 5 % CO2 and set to 37 °C. All culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Merelbeke, Belgium). To induce apoptosis, cells were treated with etoposide at 50 μg/ml (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The etoposide and doxorubicine (another apoptotic agent tested) dose-response curves of granulosa cells are provided in Online Resource 1. To induce hypoxia, cells were cultured in tri-gas (CO2, atmospheric O2, and N2), where nitrogen supply is used to displace and reduce O2 levels to 1 % (HeracellTM 150, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 48 h at 37 °C. The anti-apoptotic Z-VAD-FMK was added at a concentration of 50 μM (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). The time and dose-response curves of granulosa cells after Z-VAD-FMK and other anti-apoptotic drugs treatment are given in Online Resource 2. The etoposide and anti-apoptotic drugs time-response curves of granulosa cell metabolic activity are provided in Online Resource 3.

WST-1 metabolic activity assay

The cell metabolic activity was estimated using a WST-1 assay (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Granulosa cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1.0 × 104 for GC1a and HGL5 cells and 2.5 × 104 for COV434 cells in 100 μl of medium per well. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, duplicate wells were treated as previously described. Experiments were repeated at least three times. After treatment, a total of 10 μl of WST-1 solution was added to each well before a second identical incubation of approximately 3 h. Sample absorbance was measured at 450 nm (OD450) and 620 nm (OD620) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Colorimetric analysis was performed using a microplate spectrophotometer (Multiskan FC, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cell metabolic activity was calculated using the following equation:

| 1 |

Flow cytometry

The apoptosis of granulosa cells was analyzed by flow cytometry after annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide double staining using a BD PharmingenTM Annexin V FITC apoptosis detection kit (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA). Granulosa cells were seeded at a density of 6.0 × 105 for GC1a and HGL5 cells and 1.25 × 106 for COV434 cells in 6-cm petri dishes. Experiments were repeated at least three times. After treatment (see above), cells were harvested with trypsin, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in binding buffer at a concentration of 1.0 × 106 cells/ml. Then, 100 μl of the cell suspension was incubated with 5 μl of annexin V-FITC and 5 μl of PI in dark for 10 min at room temperature according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At the end of the incubation, 400 μl of binding buffer was added to the solution. Viable and apoptotic cells were detected using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Subsequently, the results were analyzed using the BD CellQuestTM Pro software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

RT real-time-PCR for mRNA quantification

Total RNA from treated granulosa cell lines was extracted using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol. One microgram of RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). RT and real-time quantitative PCR were performed using specific primers and Brilliant SYBR GREEN QPCR master mix (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) on a LightCycler® 480 (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Sequence primers for the target genes were B2M forward 5′-TGCTGTCTCCATGTTTGATGTATCT-3′ and reverse 5′-TCTCTGCTCCCCACCTCTAAGT-3′; RPL13A forward 5′-CCTGGAGGAGAAGAGGAAAGAGA-3′ and reverse 5′-TTGAGGACCTCTGTGTATTTGTCAA-3′; TBP forward 5′-TGCACAGGAGCCAAGAGTGAA-3′ and reverse 5′-CACATCACAGCTCCCCACCA-3′; p53 forward 5′-TCCGAGTGGAAGGAAATTTGCGTG-3′ and reverse 5′-GAGTCTTCCAGTGTGATGATGGTG-3′; Bax forward 5′-TGCCAGCAAACTGGTGCTCAA-3′ and reverse 5′-GCCCATCTTCTTCCAGATGGT-3′; and Bcl-xl forward 5′-GCGTGGAAAGCGTAGACAAG-3′ and reverse 5′-AAAAGTATCCCAGCCGCCGT-3′. Gene expression values were normalized to the geometric mean of three housekeeping genes (B2M, L13A, and TBP), and mRNA expression levels were quantified using the ∆CT method [43].

Western blot analysis

For the preparation of total cell extracts, samples were washed three times with cold PBS and lysed in an appropriate amount of radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The lysate was collected and the protein concentration was determined using a DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of protein were denatured and separated by electrophoresis on 10 or 12 % SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PerkinElmer) at 100 V for 1 h. After blocking, proteins were incubated with respective primary antibodies in blocking solution according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was added to the membrane followed by a 1-h incubation at room temperature. After sequential washing of the membranes to remove excess secondary antibody, signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a LAS4000 imager (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). Blocking solution, primary antibody, and their appropriate secondary antibodies are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primary and secondary antibodies used for Western blotting

| Blocking solutions | Primary antibodies | Secondary antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| BSA 2 % | P53 (Calbiochem, OP53) 1/2000 ON 4 °C | Horse anti-mouse 1/2000 (Cell Signaling #7076) |

| Milk 5 % | Bax (Santa Cruz, sc-7480) 1/500 ON 4 °C | Horse anti-mouse 1/2000 (Cell Signaling #7076) |

| Milk 5 % | Bcl-xl (Cell Signaling, #2764) 1/1000 ON 4 °C | Goat anti-rabbit 1/2000 (Cell Signaling #7074) |

| Milk 5 % | PARP (Cell Signaling, #9542) 1/1000 ON 4 °C | Swine anti-rabbit 1/1000 (Dako P0399) |

| Milk 5 % | Actine (Sigma, A2066) 1/1000 1 h RT | Swine anti-rabbit 1/1000 (Dako P0217) |

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are expressed as means ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were conducted with the GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA, USA) using a Mann–Whitney test for comparisons between two groups. A p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Cell viability assessment in etoposide and Z-VAD-FMK-treated cells

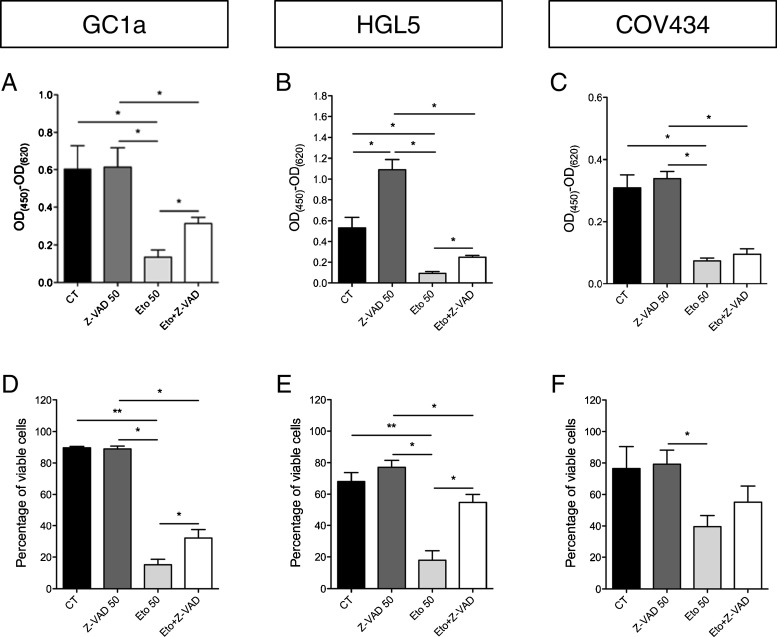

To evaluate the anti-apoptotic effect of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK on the three granulosa cell lines, apoptosis was induced by etoposide, a topoisomerase II inhibitor that stabilizes DNA double strand breaks. The WST-1 assays indicate that etoposide significantly decreased the metabolic activity of cells. These observations were confirmed, as the number of viable cells was reduced by etoposide as shown by FACS analyses after annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide double staining. Z-VAD-FMK treatment inhibited the etoposide-induced decrease in metabolic activity of the granulosa cells. Flow cytometry experiments also indicated a protective effect of Z-VAD-FMK against etoposide by showing a higher number of viable cells when the cells were treated with both drugs compared with treatment with etoposide alone (Fig. 1a–f).

Fig. 1.

Granulosa cell metabolic activity and viability after pro- and anti-apoptotic drug treatment. Evaluation of the metabolic activity as measured by WST-1 assay (a–c), and the percentage of viable cells as shown by flow cytometry analyses (d–f), of the three granulosa cell lines after etoposide and Z-VAD-FMK treatments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

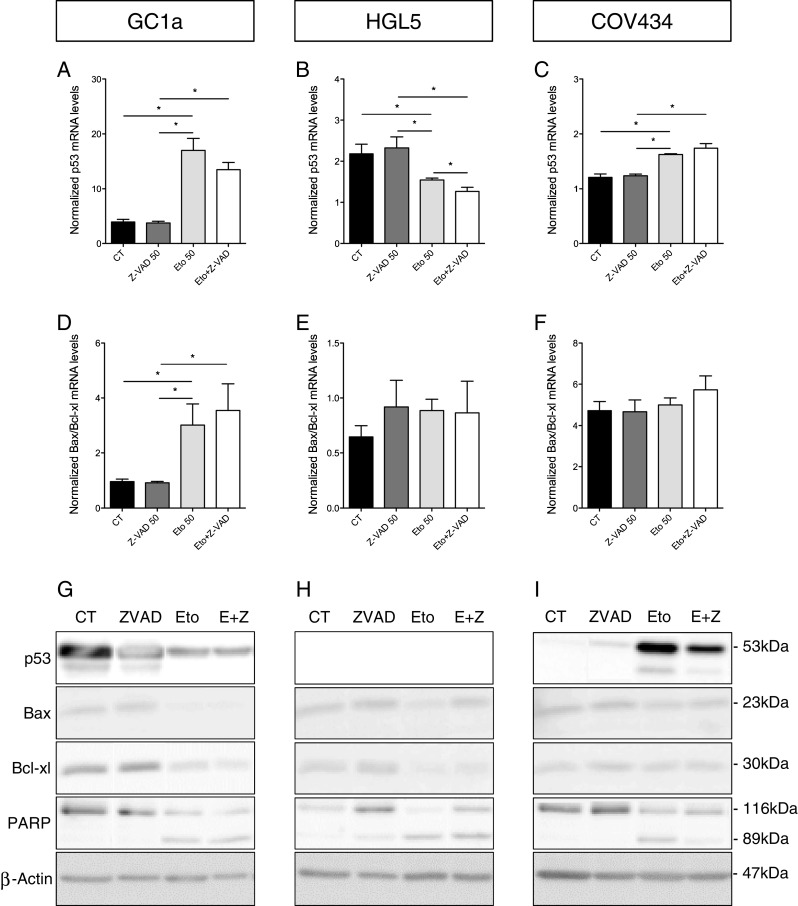

Expression of apoptosis-related molecules in etoposide and Z-VAD-FMK-treated cells

The effect of etoposide and Z-VAD-FMK treatment on the apoptotic pathway was studied at the mRNA and protein levels. As shown by RT-qPCR, the p53 mRNA expression levels were increased by etoposide in the GC1a and COV434 cell lines. In contrast, in the HGL5 cells, the p53 mRNA expression levels decreased under etoposide treatment. No protective effects from Z-VAD-FMK treatment were detected (Fig. 2a–c). In the GC1a cells, the ratio between pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules (Bax and Bcl-xl, respectively) was increased by etoposide but was not modulated in the other granulosa cell lines. Anti-apoptotic treatment had no effect on Bax/Bcl-xl mRNA expression levels in all cell lines (Fig. 2d–f).

Fig. 2.

mRNA and protein expression levels of pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules after etoposide and Z-VAD-FMK treatment. Expression levels of p53 mRNA (a–c). The ratio between mRNA expression levels of pro- and anti-apoptotic (Bax and Bcl-xl, respectively) molecules (d–f). Representative images of Western blot highlighting the expression of proteins involved in the apoptosis pathway (g–i). ß-Actin was used as a loading control. *p < 0.05

Using Western blotting, we studied the expression levels of the apoptosis-related proteins. In the GC1a cells, p53 expression was decreased by etoposide, whereas the opposite was observed in the COV434 cells. The addition of Z-VAD-FMK decreased p53 expression in the COV434 cells but had no effect in the GC1a cells. p53 was not detectable in HGL5 cells. Under etoposide treatment, Bax expression was decreased in all cell lines and Bcl-xl was decreased in the GC1a and HGL5 cells. For all cell lines, treatments with both Z-VAD-FMK and etoposide did not have any effects on Bax and Bcl-xl expression levels compared with etoposide treatments alone. When the cells were treated with both etoposide and Z-VAD-FMK, full-length PARP expression was increased in the HGL5 cells but the expression of the cleaved form was not modulated. In the COV434 cells, cleaved PARP expression was decreased and there was an increase in the expression of the full-length form. In the GC1a cells, Z-VAD-FMK did not modulate the effects of etoposide (Fig. 2g–i).

Cell viability assessment under hypoxia

To reproduce the early ischemic phase that occurs after ovarian fragment transplantation, cells were cultured without serum at 1 % O2. Under these hypoxic conditions, the metabolic activity of the granulosa cells was decreased due to serum starvation. Flow cytometry analyses confirmed that this deprivation induced HGL5 cell death. However, through these two analytical methods, we did not observed any protective effects attributable to Z-VAD-FMK (Fig. 3a–f).

Fig. 3.

Granulosa cell metabolic activity and viability under hypoxia (1 % O2). Evaluation of the metabolic activity (a–c) and the percentage of viable cells (d–f) maintained in hypoxia with or without serum and with Z-VAD-FMK treatment. *p < 0.05

Expression of apoptosis-related molecules under hypoxia

In all cell lines, no variations in the mRNA expression levels of p53 were found (Fig. 4a–c). A decrease in the ratio of Bax and Bcl-xl was observed under serum starvation in GC1a cells but no effect is detected in other cell lines (Fig. 4d–f).

Fig. 4.

mRNA and protein expression levels of pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules under hypoxia (1 % O2). The evolution of mRNA expression levels of p53 (a–c) and Bax/Bcl-xl (d–f) in the three granulosa cell lines. Representative images of Western blot experiments showing apoptosis-related protein expression in granulosa cells 48 h after the initiation of hypoxia (g–i). ß-Actin was used as a loading control. *p < 0.05

In the GC1a cells, the p53 expression level was not modulated by hypoxia, serum starvation, or Z-VAD-FMK. There was a slight decrease in the level of p53 under serum starvation in the COV434 cells; however, anti-apoptotic drug treatment increased the level of p53. In the HGL5 cells, p53 protein remained undetectable. The expressions of pro- and anti-apoptotic molecules were not modulated under any of our experimental conditions or in our cell lines. PARP was never cleaved when the cells were under hypoxia or serum starvation. However, full-length PARP expression levels increased in the GC1a and HGL5 cells after Z-VAD-FMK treatment (Fig. 4g–i).

Discussion

In this in vitro study, we used three human granulosa cell lines (GC1a, HGL5, and COV434) at low oxygen concentration (1 % O2) without serum to mimic post-grafting ischemic conditions. Our goal was to evaluate the efficacy of the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK to prevent ovarian granulosa cell death. Indeed, in vivo granulosa cells are of paramount importance for follicle survival due to their influence on oocyte maturation. Moreover, the apoptosis of granulosa cells has been shown to play an important role in follicular atresia [44, 23].

In previous studies, it was demonstrated that the short-term culture of pancreatic islets and mice ovarian cortex cryopreserved with Z-VAD-FMK reduced post-transplantation apoptosis and subsequently improved the outcome of grafts [37, 34]. Moreover, Z-VAD-FMK has been found to abolish the ischemia-mediated activation of caspases [35]. Based on these data, Z-VAD-FMK appears to be an interesting compound to treat ovarian biopsy at the time of transplantation in order to minimize the effects of ischemic damages and to improve ovarian tissue recovery.

The present study demonstrates that Z-VAD-FMK was able to prevent etoposide-induced apoptosis in three different human granulosa cell lines. We further tested this protective effect against cell death under hypoxia and serum starvation. However, our data suggest that the apoptotic pathway was not activated by hypoxic or serum starvation culture conditions in the selected granulosa cell lines. We found no modulation in the expression of apoptosis-related molecules under low oxygen conditions. However, modifications in the expression levels of hypoxia-sensitive genes, such as VEGF and PAI-1, were confirmed (data not shown), which indicated that granulosa cells do respond to hypoxia.

Even though the apoptotic pathway was not activated in our ischemic model, these cells were also not sensitive to low oxygen concentrations or serum starvation. Indeed, as shown by the FACS analyses, the percentage of viable cells was significantly reduced only in the HGL5 cells under stress conditions. Therefore, the in vitro ischemic model used in our study is not suitable for our purposes. However, these data do not collectively indicate that Z-VAD-FMK will be inefficient in vivo. The low rate of cell death could be attributed to the development of high resistance to stress following the modifications that granulosa cells underwent to become immortal [41]. To test this hypothesis, we observed that cell death in the ischemic model was only observed in the HGL5 cell line in which p53, a key factor in the maintenance of genomic stability, was not detected. In vivo, granulosa cells displayed different properties related to their localization and function around the oocyte [45]. Therefore, it is not very surprising that the three different cell lines display different responses to stress injuries. Primary granulosa cell culture in ischemic conditions could be more appropriate for the study of the effectiveness of Z-VAD-FMK in vitro.

In addition, HGL5 cell death was demonstrated in the ischemic model despite the quiescence of the apoptotic pathway, suggesting that other cell death pathways were involved. In the case of ovarian damage due to toxicant exposure, there was some evidence that follicular loss can occur via non-apoptotic mechanisms, such as autophagy [46]. In contrast to apoptosis, autophagy is a “self-eating” process in which autophagosome vesicles envelop dysfunctional or unnecessary proteins and organelles in the cytoplasm before elimination by lysosomal proteases. It has been demonstrated that during starvation, cellular components can be degraded to promote cell survival and maintain cellular energy levels but if the nutrient supply was not restored, cell death was induced [47]. Thus, examination of the role of autophagy in follicular loss after ovarian tissue transplantation should be explored. It has been well-established that several causes of follicular loss after transplantation coexist. However, the mechanisms regulating follicular death in grafted tissue are poorly understood. A better comprehension of these processes would result in better treatments of the ovarian fragments and improve ovarian tissue recovery and subsequently follicular preservation.

In conclusion, the ischemic model used in our study failed to induce ovarian granulosa cell death. The potential protective effect of Z-VAD-FMK in vitro for application in ovarian tissue transplantation could not be shown. Because several studies have already identified Z-VAD-FMK as an efficient caspase inhibitor to prevent ischemia/reperfusion injuries in different tissues, it will be interesting to investigate its effect in vivo in a xenograft model. Anti-apoptotic drugs should be combined with pro-angiogenic and anti-oxidative molecules to act on the previously mentioned conditions that are responsible for accelerated follicular loss after transplantation.

Electronic supplementary materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Doxorubicin and etoposide dose–response curves in granulosa cells. The metabolic activity of GC1a (a) and HGL5 (b) cells treated with the indicated dose of doxorubicin or etoposide for 24 hours. Similar levels of cell death were obtained for identical concentrations of etoposide within the two cell lines. Etoposide at 50 μg/ml induced slightly less than 50 % cell death. (PPTX 111 kb).

Time- and dose–response curves for anti-apoptotic drugs in granulosa cells. The metabolic activity, measured using the WST-1 method, of GC1a (a) and HGL5 (b) cells treated with the indicated dose of imatinib, nilotinib, sphingosine-1-phosphate and Z-VAD-FMK for 24 and 48 hours. At low (10 μM) and high (50 μM) concentrations, Z-VAD-FMK did not decrease the metabolic activity of the granulosa cells. (PPTX 125 kb).

Time-response curve of granulosa cell metabolic activity after treatment with etoposide and anti-apoptotic drugs. In combination with etoposide, Z-VAD-FMK preserved a greater percentage of the metabolic activity of GC1a (a) and HGL5 (b) cells. (PPTX 124 kb).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Erika Konradowski and Nathalie Lefin for their excellent technical assistance. The authors also thank Dr. S. Ormenese and R. Stephan from the GIGA-Imaging and Flow Cytometry facility for their support with FACS analyzes.

M.F. is Televie granted PhD students (F.R.S.-FNRS, Belgium). C.M. is Research Associate from the F.R.S.-FNRS (Belgium). This work was supported by grants from the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique Médicale, the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique-FNRS (F.R.S.-FNRS, Belgium), the Foundation against Cancer (foundation of public interest, Belgium), the Fonds spéciaux de la Recherche (University of Liège), the Centre Anticancéreux près l’Université de Liège, the Fonds Léon Fredericq (University of Liège), the Direction Générale Opérationnelle de l’Economie, de l’Emploi et de la Recherche from the S.P.W. (Région Wallonne, Belgium), and the Plan National Cancer (Service Public Fédéral).

Footnotes

Capsule

Granulosa cell lines are resistant to low oxygen concentration (1 % O2) and the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK could ensure follicular maintenance after ovarian tissue auto-transplantation.

The errors occurred in Figure 2, specifically in panels G, H, and I of the published article.

The errors were due to the splicing of Western blot images to align the presentation of the conditions with other figures in the paper (specifically with Fig 2 a-f), which could mislead or confuse the interpretation. Additionally, an important blot for p53 in panel H was omitted during the assembly of the figure for publication.

• Figure 2G: The entire panel will be replaced with an unspliced version of the Western blot.

• Figure 2H: This panel will be replaced with an unspliced version of the Western blot and will now include the previously omitted p53 negative data.

• Figure 2I: This panel will also be replaced with an unspliced version.

We confirm that these changes do not affect the paper's overall results and conclusions. The corrected figures provide a more transparent and accurate visual representation of the data without altering the scientific conclusions derived from the original dataset. The integrity of the findings and their implications remain intact, as the experimental outcomes are consistently supported by the quantitative data and other figures within the publication.

Change history

6/22/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s10815-024-03152-3

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10815-015-0536-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Transplantation of ovarian tissue. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28(8):1188–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imbert R, Moffa F, Tsepelidis S, Simon P, Delbaere A, Devreker F et al. Safety and usefulness of cryopreservation of ovarian tissue to preserve fertility: a 12-year retrospective analysis. Hum Reprod. 2014. doi:10.1093/humrep/deu158 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Nugent D, Meirow D, Brook PF, Aubard Y, Gosden RG. Transplantation in reproductive medicine: previous experience, present knowledge and future prospects. Hum Reprod Update. 1997;3(3):267–80. doi: 10.1093/humupd/3.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aubard Y, Piver P, Cogni Y, Fermeaux V, Poulin N, Driancourt MA. Orthotopic and heterotopic autografts of frozen-thawed ovarian cortex in sheep. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(8):2149–54. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.8.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baird DT, Webb R, Campbell BK, Harkness LM, Gosden RG. Long-term ovarian function in sheep after ovariectomy and transplantation of autografts stored at −196 C. Endocrinology. 1999;140(1):462–71. doi: 10.1210/en.140.1.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nisolle M, Casanas-Roux F, Qu J, Motta P, Donnez J. Histologic and ultrastructural evaluation of fresh and frozen-thawed human ovarian xenografts in nude mice. Fertil Steril. 2000;74(1):122–9. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nugent D, Newton H, Gallivan L, Gosden RG. Protective effect of vitamin E on ischaemia-reperfusion injury in ovarian grafts. J Reprod Fertil. 1998;114(2):341–6. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1140341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamura K, Cheng Y, Suzuki N, Deguchi M, Sato Y, Takae S, et al. Hippo signaling disruption and Akt stimulation of ovarian follicles for infertility treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(43):17474–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312830110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsueh AJ, Kawamura K, Cheng Y, Fauser BC. Intraovarian control of early folliculogenesis. Endocr Rev. 2015;36(1):1–24. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Van der Elst J, Van den Broecke R, Dhont M. Early massive follicle loss and apoptosis in heterotopically grafted newborn mouse ovaries. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(3):605–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.3.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H, Lee HH, Lee HC, Ko DS, Kim SS. Assessment of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and apoptosis in the ovarian graft: can exogenous gonadotropin promote angiogenesis after ovarian transplantation? Fertil Steril. 2008;90(4):1550–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buccione R, Schroeder AC, Eppig JJ. Interactions between somatic cells and germ cells throughout mammalian oogenesis. Biol Reprod. 1990;43(4):543–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.4.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siebzehnrubl E, Kohl J, Dittrich R, Wildt L. Freezing of human ovarian tissue--not the oocytes but the granulosa is the problem. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;169(1–2):109–11. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(00)00362-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koos RD. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth/permeability factor in the rat ovary following an ovulatory gonadotropin stimulus: potential roles in follicle rupture. Biol Reprod. 1995;52(6):1426–35. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod52.6.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shikanov A, Zhang Z, Xu M, Smith RM, Rajan A, Woodruff TK et al. Fibrin Encapsulation and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Delivery Promotes Ovarian Graft Survival in Mice. Tissue engineering Part A. 2011. doi:10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Abir R, Fisch B, Jessel S, Felz C, Ben Haroush A, Orvieto R. Improving posttransplantation survival of human ovarian tissue by treating the host and graft. Fertil.Steril. 2011; p. 1205–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Labied S, Delforge Y, Munaut C, Blacher S, Colige A, Delcombel R, et al. Isoform 111 of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF111) improves angiogenesis of ovarian tissue xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95(3):426–33. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318279965c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Ying YF, Ouyang YL, Wang JF, Xu J. VEGF and bFGF increase survival of xenografted human ovarian tissue in an experimental rabbit model. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(10):1301–11. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0043-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry L, Labied S, Fransolet M, Kirschvink N, Blacher S, Noel A, et al. Isoform 165 of vascular endothelial growth factor in collagen matrix improves ovine cryopreserved ovarian tissue revascularisation after xenotransplantation in mice. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0015-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fransolet M, Henry L, Labied S, Masereel MC, Blacher S, Noel A, et al. Influence of mouse strain on ovarian tissue recovery after engraftment with angiogenic factor. J Ovarian Res. 2015;8(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13048-015-0142-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Havelock JC, Rainey WE, Carr BR. Ovarian granulosa cell lines. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;228(1–2):67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldar S, Khaniani MS, Derakhshan SM, Baradaran B. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis and roles in cancer development and treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(6):2129–44. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.6.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hussein MR. Apoptosis in the ovary: molecular mechanisms. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(2):162–77. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutt KJ. The role of BH3-only proteins in apoptosis within the ovary. Reproduction. 2015;149(2):R81–9. doi: 10.1530/rep-14-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita Y, Perez GI, Paris F, Miranda SR, Ehleiter D, Haimovitz-Friedman A, et al. Oocyte apoptosis is suppressed by disruption of the acid sphingomyelinase gene or by sphingosine −1-phosphate therapy. Nat Med. 2000;6(10):1109–14. doi: 10.1038/80442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hancke K, Strauch O, Kissel C, Gobel H, Schafer W, Denschlag D. Sphingosine 1-phosphate protects ovaries from chemotherapy-induced damage in vivo. Fertil Steril. 2007;87(1):172–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaya H, Desdicioglu R, Sezik M, Ulukaya E, Ozkaya O, Yilmaztepe A, et al. Does sphingosine-1-phosphate have a protective effect on cyclophosphamide- and irradiation-induced ovarian damage in the rat model? Fertil Steril. 2008;89(3):732–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zelinski MB, Murphy MK, Lawson MS, Jurisicova A, Pau KY, Toscano NP, et al. In vivo delivery of FTY720 prevents radiation-induced ovarian failure and infertility in adult female nonhuman primates. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(4):1440–5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng Y, Xu Z, Wu F, Chen W, Xie S, Liu J et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate suppresses cyclophosphamide induced follicle apoptosis in human fetal ovarian xenografts in nude mice. Fertility and sterility. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Hancke K, Walker E, Strauch O, Gobel H, Hanjalic-Beck A, Denschlag D. Ovarian transplantation for fertility preservation in a sheep model: can follicle loss be prevented by antiapoptotic sphingosine-1-phosphate administration? Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25(12):839–43. doi: 10.3109/09513590903159524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jee BC, Lee JR, Youm H, Suh CS, Kim SH, Moon SY. Effect of sphingosine-1-phosphate supplementation on follicular integrity of vitrified-warmed mouse ovarian grafts. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;152(2):176–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soleimani R, Heytens E, Oktay K. Enhancement of neoangiogenesis and follicle survival by sphingosine-1-phosphate in human ovarian tissue xenotransplants. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e19475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai YC, Tzeng CR, Wang CW, Hsu MI, Tan SJ, Chen CH. Antiapoptotic Agent Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Protects Vitrified Murine Ovarian Grafts. Reproductive sciences. 2013. doi:10.1177/1933719113493515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Zhang JM, Li LX, Yang YX, Liu XL, Wan XP. Is caspase inhibition a valid therapeutic strategy in cryopreservation of ovarian tissue? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2009;26(7):415–20. doi: 10.1007/s10815-009-9331-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cursio R, Gugenheim J, Ricci JE, Crenesse D, Rostagno P, Maulon L, et al. Caspase inhibition protects from liver injury following ischemia and reperfusion in rats. Transpl Int. 2000;13(1):S568–72. doi: 10.1007/s001470050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Himi T, Ishizaki Y, Murota S. A caspase inhibitor blocks ischaemia-induced delayed neuronal death in the gerbil. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10(2):777–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montolio M, Tellez N, Biarnes M, Soler J, Montanya E. Short-term culture with the caspase inhibitor z-VAD.fmk reduces beta cell apoptosis in transplanted islets and improves the metabolic outcome of the graft. Cell Transplant. 2005;14(1):59–65. doi: 10.3727/000000005783983269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stroh C, Cassens U, Samraj AK, Sibrowski W, Schulze-Osthoff K, Los M. The role of caspases in cryoinjury: caspase inhibition strongly improves the recovery of cryopreserved hematopoietic and other cells. The FASEB Journal. 2002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Nitta M, Katabuchi H, Ohtake H, Tashiro H, Yamaizumi M, Okamura H. Characterization and tumorigenicity of human ovarian surface epithelial cells immortalized by SV40 large T antigen. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81(1):10–7. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okamura H, Katabuchi H, Ohba T. What we have learned from isolated cells from human ovary? Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;202(1–2):37–45. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(03)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rainey WH, Sawetawan C, Shay JW, Michael MD, Mathis JM, Kutteh W, et al. Transformation of human granulosa cells with the E6 and E7 regions of human papillomavirus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78(3):705–10. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.3.8126145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang H, Vollmer M, De Geyter M, Litzistorf Y, Ladewig A, Dürrenberger M, et al. Characterization of an immortalized human granulosa cell line (COV434) Mol Hum Reprod. 2000;6(2):146–53. doi: 10.1093/molehr/6.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C (T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsueh AJ, Billig H, Tsafriri A. Ovarian follicle atresia: a hormonally controlled apoptotic process. Endocr Rev. 1994;15(6):707–24. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-6-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dzafic E, Stimpfel M, Virant-Klun I. Plasticity of granulosa cells: on the crossroad of stemness and transdifferentiation potential. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(10):1255–61. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gannon AM, Stampfli MR, Foster WG. Cigarette smoke exposure leads to follicle loss via an alternative ovarian cell death pathway in a mouse model. Toxicol Sci. 2012;125(1):274–84. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(9):741–52. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Doxorubicin and etoposide dose–response curves in granulosa cells. The metabolic activity of GC1a (a) and HGL5 (b) cells treated with the indicated dose of doxorubicin or etoposide for 24 hours. Similar levels of cell death were obtained for identical concentrations of etoposide within the two cell lines. Etoposide at 50 μg/ml induced slightly less than 50 % cell death. (PPTX 111 kb).

Time- and dose–response curves for anti-apoptotic drugs in granulosa cells. The metabolic activity, measured using the WST-1 method, of GC1a (a) and HGL5 (b) cells treated with the indicated dose of imatinib, nilotinib, sphingosine-1-phosphate and Z-VAD-FMK for 24 and 48 hours. At low (10 μM) and high (50 μM) concentrations, Z-VAD-FMK did not decrease the metabolic activity of the granulosa cells. (PPTX 125 kb).

Time-response curve of granulosa cell metabolic activity after treatment with etoposide and anti-apoptotic drugs. In combination with etoposide, Z-VAD-FMK preserved a greater percentage of the metabolic activity of GC1a (a) and HGL5 (b) cells. (PPTX 124 kb).