Abstract

Background

131I and 211At are used in nuclear medicine and accumulate in the thyroid gland and may impact normal thyroid function. The aim of this study was to determine transcriptional profile variations, assess the impact on cellular activity, and identify genes with biomarker properties in thyroid tissue after 131I and 211At administration in mice.

Methods

To further investigate thyroid tissue transcriptional responses to 131I and 211At administration, we generated a new transcriptional dataset that includes re-evaluated raw intensity values from our previous 131I and 211At studies. Differential transcriptional profiles were identified by comparing treated and mock-treated samples using Nexus Expression 3.0 software. Further data analysis was performed using R/Bioconductor and IPA.

Results

A total of 1144 genes were regulated. Hierarchical clustering subdivided the groups into two clusters containing the lowest and highest absorbed dose levels, respectively, and revealed similar transcriptional regulation patterns for many kallikrein-related genes. Twenty-seven of the 1144 genes were recurrently regulated after 131I and 211At exposure and divided into six clusters. Several signalling pathways were affected, including calcium, integrin-linked kinase, and thyroid cancer signalling, and the peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor network.

Conclusions

Substantial changes in transcriptional regulation were shown in 131I and 211At-treated samples, and 27 genes were identified as potential biomarkers for 131I and 211At exposure. Clustering revealed distinct differences between transcriptional profiles of both similar and different exposures, demonstrating the necessity for better understanding of radiation-induced effects on cellular activity. Additionally, ionizing radiation-induced changes in kallikrein gene expression and identified canonical pathways should be further assessed.

Keywords: Radiation biology, Microarray, Radiation biomarkers, Radionuclide therapy, Transcriptomics, Radiogenomics

Background

Medical applications for radionuclides are rapidly developing. The β particle-emitting 131I is frequently included in therapy regimens of various thyroid disorders due to selective uptake of the isotope in thyroid tissue and is also administered bound to tumour-seeking agents for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes [1–4]. The α particle-emitting 211At is a suitable therapeutic radionuclide due to, e.g., a nearly optimal therapeutic linear energy transfer value of emitted α particles of 98.8 keV/μm [5]. 211At-labelled tumour-seeking pharmaceuticals have been utilized both in humans and in animals [6–8]. Similar to unbound 131I, selective uptake of unbound 211At also occurs in thyroid tissue [9–11], and administration of free 131I and 211At or 131I- and 211At-labelled radiopharmaceuticals have been shown to result in thyroid irradiation [6, 12]. Additionally, nuclear accidents often involve an atmospheric release of 131I, as was the case in connection with the Chernobyl accident, which resulted in an increased incidence of thyroid cancer in children [13, 14].

Despite the risk of exposing thyroid tissue to 131I and 211At, the understanding of radiation-induced effects is far from complete and molecular biomarkers of absorbed dose or radiation-induced effects on thyroid tissue are yet to be identified. Biomarkers are useful to indicate achieved therapeutic effects or estimate risk exposure and evaluate the quality and severity of side effects. RNA microarray analysis is a semi-quantitative method to identify changes in genome-wide transcriptional patterns between two or more samples. The result is a transcriptional profile, i.e. a snapshot of the radiation-induced cellular activity at the mRNA level. This can be used to determine the impact of radiation on biological functions and canonical pathways, to predict upstream regulation of target molecules, and for biomarker discovery without the risk of bias in focusing on a specific set of signalling pathways only.

Few investigations on global gene expression effects of α and β particle irradiation have been performed in normal (thyroid) tissue in vivo. There are, however, a few in vitro studies on global gene expression in fibroblasts and cancer cells after α particle exposure [15, 16]. Additionally, effects on gene expression for a set of pre-defined genes after α particle irradiation have been measured both in cancer cells in vitro and in vivo in xenografted tumours [17–19]. Previously, we have published results showing substantial differences between transcriptional profiles in thyroid tissue in vivo after different 131I or 211At exposures, varying absorbed dose, dose rate and time after administration [20–22]. We then identified potential biomarkers for each type of exposure separately and concluded that biological response to radiation is complex and that it is difficult to predict or extrapolate radiation-induced effects for other exposure parameters.

The aim of this work was to re-evaluate the previously obtained transcriptional response in thyroid after administration of 131I− and free 211At in mice from different exposure conditions to gain a better understanding of variations in transcriptional regulation on absorbed dose, dose rate, time after administration and radiation quality.

Methods

Study design

In this study, we further investigate the thyroid transcriptional response to 131I and 211At exposure by using normalized intensity values from three different experiments where separate analyses of each experiment have been published elsewhere [20–22]. All normalized intensity values (normalization was performed according to experiment) from these three experiments were imported together into Nexus Expression 3.0 (BioDiscovery; El Segundo, CA) for filtering, linear modelling and determination of differentially expressed genes.

No new tissue sampling and analysis was thus performed in this study, but a reanalysis of all these data together in a new analysis by Nexus Expression. Data presented in the present work are therefore novel and have not been previously published.

A brief summary of the methods used in the three original studies is as follows: a total of 44 female Balb/c nude mice (CAnN.Cg-Foxn1nu/Crl, Charles River Laboratories International, Inc., Salzfeld, Germany) (n = 2–3 per group) were i.v. injected with various amounts of 131I or 211At in the tail vein and killed at 1, 6, 24 or 168 h after administration, or mock-treated (Table 1). Thyroid, kidney, liver, lung and spleen tissue samples were collected and immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. The present study contains data on transcriptional changes in thyroid glands. The transcriptional response in the kidneys, livers, lungs and spleens has been published elsewhere [23–25].

Table 1.

Number of regulated genes in thyroid tissue in mice 1–168 h after administration of 131I and 211At

| Radionuclide | Δt (h) | A (kBq) | D (Gy) | Mice (n) | Regulated genes (no.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Up | Down | |||||

| 211At | 1 | 1.7 | 0.023 | 3 | 210 | 92 | 118 |

| 100 | 1.4 | 3 | 630 | 345 | 285 | ||

| 6 | 1.7 | 0.32 | 3 | 170 | 51 | 119 | |

| 7.5 | 1.4 | 3 | 290 | 116 | 174 | ||

| 24 | 0.064 | 0.05 | 3 | 360 | 254 | 106 | |

| 0.64 | 0.5 | 3 | 157 | 95 | 62 | ||

| 1.7 | 1.4 | 3 | 359 | 149 | 210 | ||

| 14 | 11 | 3 | 464 | 339 | 125 | ||

| 42 | 32 | 3 | 357 | 251 | 106 | ||

| 168 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 3 | 136 | 49 | 87 | |

| 131I | 24 | 13 | 0.85 | 2 | 227 | 101 | 126 |

| 130 | 8.5 | 2 | 266 | 138 | 128 | ||

| 260 | 17 | 2 | 55 | 37 | 18 | ||

Absorbed dose was calculated using MIRD formalism

Abbreviations: Δt exposure time, A injected activity, D absorbed dose

The methods for determination of absorbed doses have been reported previously with separate analysis of each experiment [20–22]. In short, the mean absorbed dose was calculated according to conventional Medical Internal Radiation Dose (MIRD) formalism. We used previously published data on relative activity concentration of 131I and 211At in thyroid in mice [26], an absorbed fraction of 0.742 and 1 for radiation emitted from 131I and 211At, respectively [27], and a standard mouse thyroid mass of 3 mg.

Gene expression analysis

Genome-wide transcriptional analysis using RNA microarray of thyroid tissue has been described elsewhere [20, 21]. Briefly, RNA samples were analysed using MouseRef-8 Whole-Genome Expression Beadchips (Illumina; San Diego, CA, USA). Nexus Expression 3.0 (BioDiscovery; El Segundo, CA) was used to identify statistically significant differentially expressed transcripts (≥1.5-fold change) with a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p value cut-off of 0.01 between irradiated and control tissues. RNA microarray data from irradiated samples were compared with RNA microarray data from control animals from each separate experiment to ensure that differential expression of genes reflects radiation-induced changes and not variations between different control groups. There was one difference in study design between the present and previous studies. In the present work, data from tissue samples from animals administered 0.064 and 0.64 kBq 211At and killed 24 h after administration were compared with data from tissue samples from control animals killed the same day. However, in the previous paper with analysis of the transcriptional response at 24 h after 211At administration, animals administered 0.064 and 0.64 kBq were compared with controls killed earlier (killed simultaneously as animals injected with 1.7, 14 and 42 kBq, also at 24 h after administration but on another day) [20]. In the present paper, the term “regulated transcripts/genes” is used synonymous to “statistically significant differentially expressed transcripts/genes”.

Hierarchical clustering of regulated transcripts according to their transcriptional regulation profile was performed using the hclust function (stats package, version 3.1.1) with the complete linkage algorithm and Lance-Williams dissimilarity update formula in the R statistical computing environment (version 0.97.551, http://www.r-project.org) [28]. Heat maps were produced using the heatmap.2 function (gplots package, version 2.14.2).

Upstream regulation, diseases and functions and canonical pathway analyses were generated using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis tool (IPA, Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com; Redwood City, CA) with Fisher’s exact test (p value <0.05).

Gene expression data discussed in this publication have been deposited at the NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO accession numbers: GSE32306 [20], GSE54594 [21] and GSE66089 [22]).

Results

Regulated genes

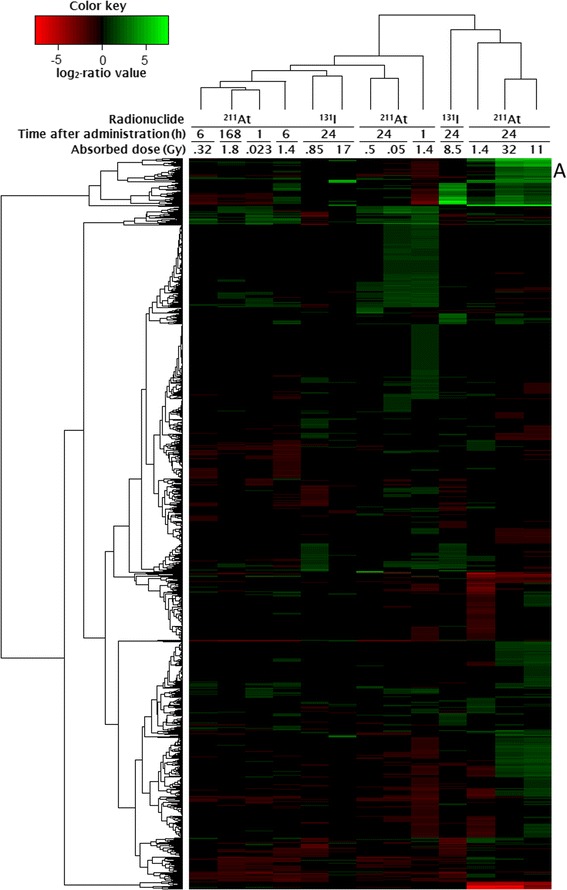

In the present study, 1144 genes (1164 transcripts) were regulated. The number of regulated genes in each group varied between 55 (17 Gy, 24 h, 131I) and 630 (1.4 Gy, 1 h 211At) (Table 1). Hierarchical clustering subdivided the exposure groups into two larger clusters: one smaller branch containing groups with higher absorbed dose levels (1.4–32 Gy from 211At and 8.5 Gy from 131I at 24 h) and a larger branch with the remaining groups (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Results from hierarchical clustering analyses of genes and exposure groups after 131I and 211At exposure. Genes were hierarchically clustered according to log2-ratio values using gplots package in R/Bioconductor. The columns represent genes and rows represent exposure type. Cluster containing kallikrein genes is denoted A

At both 1 h and 6 h after 211At administration, a higher absorbed dose/dose rate resulted in a higher number of regulated genes (Table 1). In contrast, at 24 h after 211At administration, the number of regulated genes varied non-monotonously with absorbed dose. A slight increase in the number of genes regulated after 131I exposure was seen between 0.85 and 8.5 Gy and a decrease between 8.5 and 17 Gy. Transcriptional profiles at 1, 6 and 168 h clustered together, with the exception of 1.4 Gy at 1 h (Fig. 1). At 24 h, the transcriptional profiles for 0.05 and 0.5 Gy clustered together while the profiles for 1.4, 11 and 32 Gy clustered together with highest similarity between 11 and 32 Gy. Furthermore, upregulation of 110 genes was shared between 0.05 and 1.4 Gy at 24 and 1 h after 211At administration, respectively. For 131I exposure, the transcriptional profiles for 0.85 and 17 Gy clustered together, whereas the response after 8.5 Gy was more similar to that after 1.4, 11 and 32 Gy at 24 h following 211At administration. In the groups exposed to 1.4 Gy, the number of regulated genes decreased from 630 to 290 between 1 and 6 h, but increased to 359 at 24 h (Table 1). Additionally, the transcriptional profiles of these groups showed little similarity in the cluster analysis (Fig. 1). Lastly, an equal amount of injected activity (1.7 kBq, 211At) resulted in 210, 170, 359 and 136 regulated genes at 0.023, 0.32, 1.4 and 1.8 Gy after 1, 6, 24 and 168 h, respectively (Table 1). The transcriptional profiles of these groups were similar and clustered together with the exception of 1.4 Gy at 24 h which was clearly different (Fig. 1).

Kallikrein 1 and kallikrein 1-related peptidases

Hierarchical clustering of all regulated transcripts revealed similar transcriptional regulation profiles for 13 kallikrein genes belonging to the peptidase S1 family (Klk1, Klk1b1, Klk1b4, Klk1b5, Klk1b8, Klk1b9, Klk1b11, Klk1b16, Klk1b21, Klk1b22, Klk1b24, Klk1b26 and Klk1b27 (A in Figs. 1 and 2). All 13 genes were upregulated at 11 and 32 Gy 24 h after 211At administration. For an absorbed dose of 1.4 Gy after 211At exposure, 9/13 kallikrein genes were upregulated at 24 h but downregulated at 1 h (three additional genes were downregulated at 1 h), while at 6 h, 1 and 4 genes were down- and upregulated, respectively. Furthermore, 4/13 genes were upregulated at 1.8 Gy 168 h after injection of 211At. At 24 h after 131I administration, 4/13 genes were upregulated after 17 Gy, but not regulated at the lower absorbed dose levels.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of 13 kallikrein genes belonging to the peptidase S1 family after 131I and 211At exposure. Values indicate fold change of differential gene expression. Green and red colours indicate up- and downregulation of genes, respectively. Higher saturation of colours indicates higher fold change

Recurrently regulated genes after 131I and 211At exposure

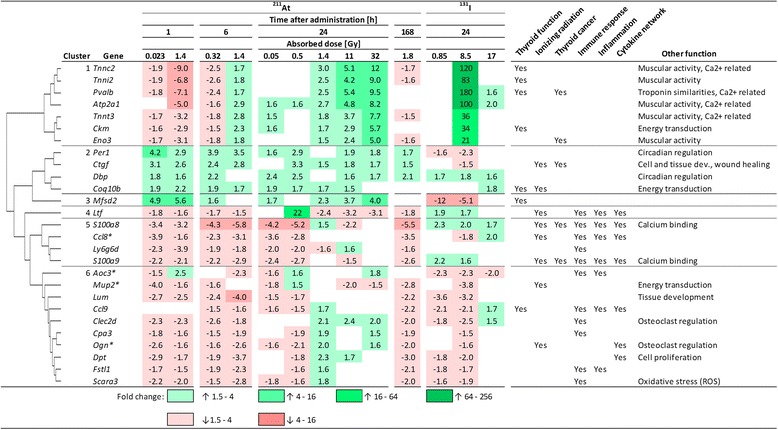

Twenty-seven of the 1144 regulated genes were regulated in ≥9 of the 13 groups (Fig. 3). Hierarchical clustering divided the 27 genes into six groups: 1) Atp2a1, Ckm, Eno3, Pvalb, Tnnc2, Tnni2, Tnnt3; 2) Coq10b, Ctgf, Dbp, Per1; 3) Mfsd2; 4) Ltf; 5) Ccl8, Ly6g6d, S100a8, S100a9 and 6) Aoc3, Ccl9, Clec2d, Cpa3, Dpt, Fstl1, Lum, Mup2, Ogn, Scara3. In cluster 1, genes were downregulated at 1 h following 211At administration. This changed at 6 h where 0.32 and 1.4 Gy showed down- and upregulation, respectively. At 24 h, the regulated genes were upregulated and, notably, the fold change increased with absorbed dose. At 24 h after 131I administration, all of these genes were upregulated with high fold changes (21–180) after 8.5 Gy, while two genes were upregulated to low extent after 17 Gy. Genes in cluster 2 were upregulated after 211At administration while 131I administration resulted in both up- and downregulation. The Mfsd2 gene, the only gene in cluster 3, was up- and downregulated after 211At and 131I administration, respectively. The Ltf gene, sole gene in cluster 4 with almost opposite regulation to Mfsd2, was downregulated after 211At administration with the exception of a 22-fold upregulation after 0.5 Gy at 24 h, and upregulated after 131I administration. Cluster 5 was similar to cluster 4, and 211At administration resulted in downregulation with few exceptions of upregulation at 24 h and 131I administration generally resulted in upregulation. Genes in cluster 6 were generally downregulated with the exception of upregulation at, e.g., 1.4–32 and 17 Gy 24 h after 211At and 131I administration, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Regulation of 27 recurrently regulated genes after 131I and 211At exposure. Values indicate fold change of differential gene expression. Green and red colours indicate up- and downregulation of genes, respectively. Higher saturation of colours indicates higher fold change. The relationships between genes and thyroid function, ionizing radiation, and thyroid cancer and biological function of genes have been assessed using literature reports

Canonical pathway analysis: calcium, integrin-linked kinase and thyroid cancer signalling

In the present study, calcium, integrin-linked kinase and thyroid cancer signalling were the top three canonical pathways generated using the IPA comparison analysis tool (Table 2). An impact on calcium signalling was statistically significant in all groups except at the two lowest and the highest absorbed dose levels 24 h after 211At and 131I administrations, respectively. Integrin-linked kinase signalling was statistically significant in all groups except at low absorbed dose levels at 1 and 24 h, and at the lowest and highest absorbed dose levels 24 h after 211At and 131I administration, respectively. Genes associated with calcium and integrin-linked kinase signalling were generally downregulated early and at low absorbed doses and upregulated at later time points and at higher absorbed doses. Thyroid cancer signalling was statistically significant in all groups except at 0.023 and 0.05 Gy, 1 and 24 h following 211At administration, respectively, and at 0.85 and 8.5 Gy 24 h after 131I administration (Table 2). Additionally, the number of genes involved in the different canonical pathways at each time point generally increased with absorbed dose (with exceptions between 11 and 32 Gy).

Table 2.

Top three Ingenuity canonical pathways enriched by genes regulated after 131I or 211At exposure

| Canonical pathway | Nuclide | Δt (h) | D (Gy) | p value | Involved moleculesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium signalling | 211At | 1 | 0.023 | 0.035 | DOWN: MYL1, TNNC2, TNNI2, TNNT3, TPM2 |

| 1.4 | 0.001 | DOWN: ACTA1, ATP2A1, ATP2A3, Calm1 (includes others), MYH1, MYH2, MYH4, MYL1, TNNC2, TNNI2, TNNT3, TPM2 UP: LETM1, PRKACA | |||

| 6 | 0.32 | <0.0005 | DOWN: ACTA1, ATP2A1, MYH1, MYL1, TNNC2, TNNI2, TNNT3, TPM2 | ||

| 1.4 | <0.0005 | DOWN: Calm1 (includes others) UP: ACTA, ATP2A1, ATP2A3, MYH, MYH2, MYH4, RYR1, TNNC2, TNNI2, TNNT3, TPM2 | |||

| 24 | 0.05 | 0.180 | UP: ATP2A1, LETM1, MYH2, RYR1, TNNT3 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.390 | UP: ATP2A1, MYH2 | |||

| 1.4 | 0.009 | DOWN: ATP2A3 UP: ACTA1, ATP2A1, MYH4, TNNC2, TNNI2, TNNT3, TPM2 | |||

| 11 | <0.0005 | DOWN: Camk2b, LETM1 UP: ACTA1, ATP2A1, ATP2A3, Calm1 (includes others), CREB3L4, MYH1, MYH2, MYH4, MYL1, RYR1, TNNC2, TNNI2, TNNT3, TP63, TPM2 | |||

| 32 | <0.0005 | DOWN: Camk2b, LETM1 UP: ACTA1, ATP2A1, ATP2A3, CREB3L4, MYH1, MYH2, MYH4, MYL1, RYR1, TNNC2, TNNI2, TNNT3, TPM2 | |||

| 168 | 1.8 | 0.027 | DOWN: TNNC2, TNNI2, TNNT3 UP: MYL1 | ||

| 131I | 24 | 0.85 | – | – | |

| 8.5 | <0.0005 | DOWN: MEF2C UP: ACTA1, ATP2A1, MYH1, MYH4, MYL1, RYR1, TNNC2, TNNI2, TNNT3, TPM2 | |||

| 17 | 0.071 | UP: ACTA1, ATP2A1 | |||

| Integrin-linked kinase signalling | 211At | 1 | 0.023 | 0.291 | DOWN: MYL1 UP: DSP, IRS2 |

| 1.4 | <0.0005 | DOWN: ACTA1, ACTB, Actn3, CCND1, ITGB6, KRT18, MYH1, MYH2, MYH4, MYL1, VIM UP: IRS2, LIMS2, SH2B2, VIM, ITGB6 UP/DOWN: PPP2R5A | |||

| 6 | 0.32 | 0.004 | DOWN: ACTA1, MYH1, MYL1 UP: DSP, IRS2, RHOU | ||

| 1.4 | 0.001 | DOWN: PPAP2B UP: ACTA1, ACTN2, Actn3, DSP, MYH1, MYH2, MYH4, RHOU | |||

| 24 | 0.05 | 0.203 | UP: ACTN2, LIMS2, MYH2, RHOT2 UP/DOWN: PPP2R5A | ||

| 0.5 | 0.413 | UP: ACTN2, MYH2 | |||

| 1.4 | 0.001 | DOWN: ACTB, CCND1, CDH1, CTNNB1, ITGB4, KRT18 UP: ACTA1, FOS, IRS2, MYH4 | |||

| 11 | <0.0005 | DOWN: Irs3, VIM UP: ACTA1, Actn3, CDH1, CREB3L4, DSP, IRS2, ITGB4, ITGB6, MYH1, MYH2, MYH4, MYL1, KRT18 | |||

| 32 | <0.0005 | UP: ACTA1, ACTN2, Actn3, CDH1, CREB3L4, DSP, IRS2, ITGB4, ITGB6, KRT18, MYH1, MYH2, MYH4, MYL1 | |||

| 168 | 1.8 | – | – | ||

| 131I | 24 | 0.85 | 0.169 | DOWN: ACTB, IRS2, PPAP2B UP: FOS | |

| 8.5 | 0.001 | DOWN: IRS2 UP: ACTA1, ACTN2, Actn3, CCND1, FOS, MYH1, MYH4, MYL1 | |||

| 17 | 0.076 | UP: ACTA1, CCND1 | |||

| Thyroid cancer signalling | 211At | 1 | 0.023 | 0.291 | DOWN: MYL1 UP: DSP, IRS2 |

| 1.4 | 0.029 | DOWN: CCND1, KLK3, NGF UP: PPARG | |||

| 6 | 0.32 | 0.040 | DOWN: NGF DOWN/UP: KLK3 | ||

| 1.4 | 0.019 | UP: NGF, KLK3, RET | |||

| 24 | 0.05 | 0.490 | DOWN/UP: KLK3 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.036 | DOWN: KLK3, UP: NGF | |||

| 1.4 | 0.004 | DOWN: CCND1, CDH1, CTNNB1 UP: KLK3 | |||

| 11 | <0.0005 | DOWN: NTRK2, NTRK3, PPARG UP: CDH1, KLK3, NGF, RET | |||

| 32 | <0.0005 | DOWN: NTRK2, NTRK3 UP: CDH1, KLK3, NGF, RET | |||

| 168 | 1.8 | 0.026 | UP: KLK3, NGF | ||

| 131I | 24 | 0.85 | 0.370 | UP: PPARG | |

| 8.5 | 0.100 | UP: CCND1, PPARG, | |||

| 17 | 0.004 | UP: CCND1, KLK3 |

DOWN and UP indicate down- and upregulation, respectively. Italics indicates no statistically significant effect on the specific canonical pathway

Abbreviations: Δt exposure time, D absorbed dose

aIPA predicts involved molecules in the form of human proteins

Diseases and function analysis: thyroid cancer and disturbed thyroid function

A diseases and function analysis related to thyroid was generated with IPA (Table 3). At 6 (1.4 Gy) and 24 h (11 and 32 Gy) after 211At administration, a relation between the transcriptional response and various thyroid cancer types was identified. Such a relation was also identified 24 h after 131I administration; however, at a lower absorbed dose level (0.85 and 8.5 Gy). Additionally, the transcriptional response was linked to altered T3 and T4 levels and to thyroid gland development at 0.32 and 32 Gy, 6 and 24 h after 211At administration, respectively.

Table 3.

Results from IPA analysis of diseases and functions related to thyroid after 131I and 211At exposure

| Nuclide | Δt (h) | D (Gy) | Disease or function | p value | Involved moleculesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 211At | 1 | 0.023 | |||

| 1.4 | |||||

| 6 | 0.32 | Dystransthyretinemic euthyroidal hyperthyroxinemia | 7.92E−03 | UP: TTR | |

| Quantity of L-triiodothyronine | 2.65E−03 | DOWN: LEP UP: TTR, UCP1 | |||

| 1.4 | Differentiated thyroid cancer | 4.63E−04 | DOWN: IDH1, MMP2, PDGFRA, RAP1GAP, TEK, TGFBR2 UP: CDKN1A, RET, | ||

| Medullary thyroid cancer | 1.01E−03 | DOWN: AMY1A (includes others), PDGFRA, TEK UP: RET, | |||

| Thyroid cancer | 1.91E−04 | DOWN: AMY1A (includes others), ECM1, IDH1, MMP2, PDGFRA, RAP1GAP, SERPINF1, TEK, TGFBR2 UP: CDKN1A, RET | |||

| 24 | 0.05 | ||||

| 0.5 | |||||

| 1.4 | |||||

| 11 | Metastasis of thyroid gland tumour | 1.21E−03 | DOWN: VIM UP: RET | ||

| Thyroid cancer | 1.18E−03 | DOWN: AMY1A (includes others), NTRK2, PPARG, SLPI, VIM UP: CDH1, PPARGC1A, PRLR, RAP1GAP, RET, SLC5A8, TP63, | |||

| 32 | Medullary thyroid cancer | 1.50E−03 | DOWN: AMY1A (includes others), NTRK2 UP: PRLR, RET | ||

| Thyroid gland development | 4.71E−03 | DOWN: HOXA5, TBX1 UP: RET | |||

| 168 | 1.8 | ||||

| 131I | 24 | 0.85 | Thyroid cancer | 1.58E−04 | DOWN: AMY1A (includes others), CDKN1A, ECM1, FLT1, MMP2, PPARGC1A, SERPINF1 UP: PPARG, SPP1, TUBA8 |

| 8.5 | Thyroid cancer | 2.05E−03 | DOWN: AMY1A (includes others), CDKN1A, MMP2, PPARGC1A, PRLR, SERPINF1 UP: CCND1, PPARG, TUBA8 | ||

| 17 | Lack of thyroid gland | 9.65E−03 | DOWN: FGF10 |

DOWN and UP indicate down- and upregulation, respectively

Abbreviations: Δt exposure time, D absorbed dose

aIPA predicts involved molecules in the form of human proteins

Upstream regulation of molecules related to peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptors

The upstream regulation analysis generated by IPA predicted upstream regulation of various molecules related to peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) (Table 4). These included PPARA, PPARD, PPARG, PPARGC1A and several PPAR-targeting drugs and/or PPAR ligands such as GW501516, mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate, pirinixic acid, Rosiglitazone and Troglitazone. IPA predicted that these upstream regulators were generally activated at 1 h, for absorbed dose ≤1.4 Gy at 24 h, and for 1.8 Gy at 168 h.

Table 4.

Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-related upstream regulators in thyroids exposed to 131I or 211At according to IPA upstream regulator analysis

| Radionuclide | 211At | 131I | |||||||||||

| Time (h) | 1 | 6 | 24 | 168 | 24 | ||||||||

| Injected activity (kBq) | 1.7 | 100 | 1.7 | 7.5 | 0.064 | 0.64 | 1.7 | 14 | 42 | 1.7 | 13 | 130 | 260 |

| Absorbed dose (Gy) | 0.023 | 1.4 | 0.32 | 1.4 | 0.05 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 11 | 32 | 1.8 | 0.85 | 8.5 | 17 |

| Gene | z score | ||||||||||||

| Pirinixic acid | 3.7 | 4.7 | −0.4 | −0.4 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 0.8 | −1.4 | n.s. | 3.5 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.2 |

| PPARA | 2.7 | 3.9 | −0.6 | −1.5 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 2.0 | −0.9 | 1.4 | 2.8 | −0.9 | −0.1 | −0.7 |

| Troglitazone | 2.7 | 5.0 | 1.6 | −0.3 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 1.1 | −2.6 | −2.2 | 1.6 | −0.1 | −1.2 | −2.0 |

| Mono-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate | 2.9 | 5.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 1.6 | n.s. | n.s. | 2.4 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.0 |

| PPARG | 2.0 | 5.2 | −0.2 | −0.9 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 1.8 | −1.1 | −0.1 | 2.6 | −0.6 | 1.3 | 0.0 |

| PPARGC1A | 2.2 | 4.1 | −0.4 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.0 |

| Rosiglitazone | 1.0 | 5.1 | −0.7 | −2.1 | 4.6 | 1.2 | 1.8 | −0.9 | −0.2 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| PPARD | 3.1 | 3.9 | 1.5 | n.s. | 3.5 | 3.7 | n.s. | −1.3 | n.s. | 2.6 | −0.8 | 0.3 | n.s. |

| GW501516 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | −1.2 | −0.3 | 0.0 |

A z score equal to or larger or less than 2 or −2 indicate activated or inhibited upstream regulator, respectively. A z score value between -2 and 2 is considered not statistically significant. n.s. indicates that IPA was not able to predict upstream regulation of that specific upstream regulator for the specific exposure condition

Discussion

In the present study, the values used to calculate absorbed dose were based on previously published 131I and 211At biodistribution data, where mice were simultaneously injected with both 131I and 211At, which allows for direct comparison of the absorbed dose per injected activity between 131I and 211At in the same animal [26]. In the present study, radioactivity measurements of individual thyroid samples would have enhanced the certainty in absorbed dose calculations but was not possible since all excised thyroid tissue was needed to ensure sufficient amount of RNA for microarray analysis. There are several important differences in the characteristics of 211At and 131I exposure: i) the difference in mean range of the α and β particles emitted (65 and 400 μm), ii) the much higher mean energy released per decay from 211At compared with 131I (7000 and 190 keV), iii) the difference in LET of particles emitted from 131I and 211At (0.25 and 98.8 keV/μm, respectively) and iv) much shorter half-life for 211At than 131I (7.2 h and 8.0 day, respectively). Taken together, 211At irradiates more heterogeneously and with higher dose rates at similar absorbed dose levels compared with 131I (and the dose rate will decline faster for 211At compared to 131I). The effects of radiation quality on global gene expression should be further studied, and to our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate such differences between 131I and 211At.

RNA microarray analysis was used to evaluate the impact of 131I and 211At exposure on global transcriptional regulation in normal mouse thyroid tissue. Regulated genes were associated with biological functions using previously published literature reports and various databases, in addition to upstream and downstream regulation analysis and canonical pathway analysis generated by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software. In total, 1144 genes were differentially regulated showing a large variation in number of genes per group. In general, hierarchical clustering divided groups that received high absorbed doses into one branch and groups receiving low absorbed doses into another. Thus, we hypothesize that the transcriptional profiles presented here may reflect intrinsic biological properties predictive of 131I and 211At absorbed dose levels at various time points.

At both 1 and 6 h, the number of regulated genes increased with absorbed dose. This was not the case for 131I or 211At exposure at 24 h, where a broader range of absorbed dose was tested. Furthermore, hierarchical clustering revealed distinct differences between the transcriptional profiles of both similar and different exposures, e.g. the transcriptional profiles for 1.4 Gy at 1 and 6 h after 211At administration were distinctly different although the absorbed dose was similar. This could in part be explained by the profound differences in dose rate; dose rate effects on the transcriptional response have previously been described in vivo following radionuclide administration [22, 25, 29]. These findings indicate that variations in the radiation-induced response with absorbed dose will be reflected in the number of regulated genes, in addition to which specific genes are regulated, although not in a clear dose-dependent manner. Instead it is likely that changes in transcriptional patterns in a specific tissue will depend with varying degree on, but not excluded to, the following parameters: exposure time, injected activity, absorbed dose, dose rate, dose distribution (e.g. frequency of non-, single- or multi-hit cells) and radiation quality. Each unique setup of these parameters may then yield a specific response in the target tissue. In addition, cells are dynamic systems with complex regulatory networks that activate cascades of downstream regulation that is sensitive to type and frequency of incoming stimulus.

It is valuable to identify genes with exposure-specific expression as they may be used as biomarkers. Biomarkers are useful to better understand the mechanisms behind the radiation-induced response. A potential application of biomarkers for ionizing radiation exposure of the thyroid might be in biological dosimetry after exposure to relatively high doses, maybe in a triage setting. In the present study, kallikrein 1 (Klk1) and 12 of 13 kallikrein 1-related (Klk1b) peptidases in the mouse genome were frequently regulated with fold change values between −3.8 and 110. The expression of these genes generally increased with absorbed dose and time after injection of 131I or 211At; however, 32 Gy resulted in less upregulation compared with 11 Gy (24 h, 211At) and the highest dose rate used (1.4 Gy, 1 h, 211At) resulted in downregulation. It is likely that the expression of Klk1 and Klk1-related peptidases depends, to a different degree, on dose rate, absorbed dose and time after injection. In a study on the rat urine proteome 24 h after 10 Gy total body irradiation, the occurrence of kallikrein 1-related peptidase b24 precursor protein increased while the kallikrein-binding serine protease inhibitor A3K precursor decreased [30]. In another study, the plasma kallikrein levels decreased with absorbed dose (0–19 Gy) at 2–24 h after local irradiation of the hind legs in tumour-bearing rats and controls [31]. Additionally, we have shown that regulation of Klk1 and Klk1-related genes in mouse thyroids after 131I exposure does not show a circadian variation [32]. We hypothesize that genes involved in the kallikrein network may be potential biomarkers of radiation exposure, but further research is warranted to elucidate the relationship between radiation exposure and kallikrein proteases and kallikrein inhibitor levels. The kallikrein genes have also been shown to contribute to the radiation-induced death of various species. After treatment with soy bean trypsin inhibitors (SBTI), the mortality rate in mice and chickens 14 days after exposure to 690 and 820 R (6.7 and 8 Gy to soft tissue), respectively, decreased from 100 to 50 % in mice and from 86 to 4 % in chickens [33]. The authors suggested that the decrease in mortality rate after administration of SBTI originated from a radioprotective effect on the vascular system with less vascular leakage and that the protease inhibited was likely tissue pre-kallikrein. We suggest that the radioprotective role of SBTI should be further assessed.

Recurrently regulated genes might be potential biomarkers and show how different exposure types influence similar/related genes and biological functions, although maybe with different magnitude and/or direction of regulation. The 27 recurrently regulated genes in the present study were divided into six clusters according to the transcriptional pattern of each individual gene following a specific exposure. In cluster 1, 211At-induced regulation was dependent on both absorbed dose and time after exposure with monotonous change in regulation at 24 h, and 8.5 Gy 131I exposure resulted in very high upregulation. Genes in cluster 1 are related to muscular activity and/or calcium activity (Atp2a1, Eno3, Pvalb, Tnnc2, Tnni2 and Tnnt3). Notably, the thyroid gland contains parafollicular cells (C-cells) that produce the calcium homeostasis regulating hormone calcitonin. Cluster 2 contains genes related to various biological functions, e.g. cellular and tissue development and wound healing (Ctgf) [34], energy transduction (Coq10b) and circadian rhythm (Dbp, Per1) [35, 36]. These genes were generally upregulated and may be indicators of radiation exposure in general. Cluster 3 consisted of only one gene (Mfsd2) that was up- and downregulated after 211At and 131I exposure, respectively, indicating a difference between radiation qualities (Ctgf, Per1, S100a8, S100a9, also showed a radiation quality dependency). No clear connection to the immune system, inflammation or the cytokine system was found for genes in clusters 1–3. However, the sole gene in cluster 4 (Ltf), all genes in cluster 5 (Ccl8, Ly6g6d, S100a8, S100a9) and a majority of genes in cluster 6 (Aoc3, Ccl9, Clec2d, Cpa3, Fstl1, Scara3) were related to the immune system in various ways, and many related to both inflammation and the cytokine network [37–47]. The cytokine encoded by Ccl9 is associated with systemic inflammation and has increased expression in macrophages after exposure to triiodothyronine [43]. Lactoferrin—in mice encoded by the Ltf gene, solely expressed in cluster 4 and generally downregulated—has been patented as a radioprotective drug and increased survival in mice exposed to 10 Gy (whole-body, external irradiation) via an impact on, e.g., cytokine regulation [38]. In cluster 5, genes were oppositely regulated when comparing 131I and 211At exposure, indicating a radiation quality-dependent immune response. In cluster 6, genes were downregulated at low absorbed doses and upregulated at high absorbed dose levels even though the shift from down- to upregulation occurred at a lower absorbed dose level for 211At compared with 131I. This suggests that the radiation-induced regulation of genes in cluster 6 is dependent on both radiation quality and absorbed dose. The 27 recurrently regulated genes can potentially be used to discriminate between several different exposure parameters, e.g. radiation quality, absorbed dose levels and time after administration, and might be considered as potential biomarkers for at least 131I and 211At exposure of thyroid. These results indicate a connection between specific exposures and biological responses, especially for the genes in clusters 4–6 that were clearly associated with immunological response, inflammation and the cytokine network. These recurrently regulated genes should be further studied to better understand their impact on radiation-induced biological responses and in particular the local and systemic effects that involve inflammation, the immune system and the cytokine network.

To assess systemic effects from 131I and 211At exposure, regulation of the 27 recurring genes was compared with transcriptional changes in the lungs, spleen, liver and kidney cortex and medulla in the same mice dissected in the present study [23, 24]. These non-thyroidal tissues, that are exposed at a much lower absorbed dose level compared with thyroid, shared regulation of 19/27 and 6/27 recurring genes after 211At and 131I exposure, respectively. Additionally, we have previously shown that the transcriptional response in the lungs, spleen, liver and kidney cortex and medulla in mice administered 131I and 211At can partly be explained as a systemic response from radiation-induced effects on thyroid [32]. One gene with potential biomarker properties is Dbp. The Dbp gene expression pattern changed in several non-thyroidal tissues after low absorbed dose level exposure to both 131I and 211At [23, 24], in kidneys in mice both early and late after 177Lu-octreotate administration [48], and in rat thyroids after 131I administration [49].

A connection to thyroid cancer was detected for 5/27 recurring genes. PVALB has been suggested as an ideal biomarker to discriminate between benign and malignant thyroid cancer [50]. ENO3 is another cancer-related gene, associated to the PAX8-PPARG fusion protein in thyroid follicular carcinomas, and upstream regulation of PPARs and PPAR-related pathways was detected in the present study [51]. The level of CTGF correlated with metastasis, tumour size and clinical stage for papillary thyroid carcinoma in a previous study [52]. Furthermore, undifferentiated thyroid carcinomas have been shown to be S100A8/9 immunopositive and both genes were associated with, e.g., inflammation-associated cancer and aggressive breast cancer [41, 53, 54].

According to the Ingenuity canonical pathway and diseases and functions analysis tool, the transcriptional response after both 131I and 211At exposure was related to thyroid cancer signalling and various thyroid cancers, respectively. It is uncertain whether induction of thyroid cancer can be detected at the transcriptional level at these early times after initiation of radiation exposure. However, according to IPA, exposure to ionizing radiation activates thyroid cancer signalling by rearrangements of RET and/or NTRK, both present in some of the exposed groups. Unfortunately, all parts of the thyroid samples from mice in the three studies this work is based on were used for microarray analysis, why further studies of genomic rearrangements were not possible from the same samples.

Additionally, KLK3 (human denotation of KLK1 in mouse) is among the involved molecules in all groups that show an impact on thyroid cancer signalling. Since IPA uses human protein nomenclature for annotation of genes, the presence of KLK3 in the IPA analysis is likely a result of regulation of mouse Klk1 and Klk1-related genes in the present study.

The number of annotated genes involved in calcium signalling generally increased with absorbed dose for 211At exposure. Several of the genes associated with these molecules could be found in cluster 1 among the 27 recurrently regulated genes (Tnni2, Tnnc2, Tnnt3 and Atp2a1). Additionally, gene products of several other recurrently regulated genes are also calcium-related according to literature reports, but not associated with calcium signalling in the IPA canonical pathway analysis. For example, the gene products of Clec2d and Ogn both inhibit osteoclasts that can release Ca2+ into the blood [55, 56]. As previously mentioned, the thyroid gland also contains parafollicular cells that produce calcitonin, a hormone partly responsible for calcium homeostasis and an inhibitor of osteoclast activity. However, the impact on calcitonin levels from 131I and 211At exposure was not investigated in the present study. A relationship between calcium and radiation-induced response has been previously reported and it was shown that calcium was required for bystander-induced apoptosis in unirradiated keratinocytes [57].

An impact on integrin-linked kinase (ILK) signalling was identified using an IPA canonical pathway analysis, and some genes associated with calcium signalling were also associated with ILK signalling in the present study. For 211At, a higher absorbed dose generally resulted in a response involving a higher number of annotated genes. For 131I exposure, ILK signalling was only statistically significant after 8.5 Gy, suggesting a difference in response due to radiation quality. In blood from mice administered with 137Cs, genes associated with integrin-signalling were found upregulated at days 2 and 3 and downregulated at days 20 and 30 (transcriptional level) [58]. No clear temporal effect on integrin-signalling was seen during the somewhat shorter time range used in the present study. Interestingly, however, in the present study, we demonstrate that genes, e.g., associated with ILK signalling were generally upregulated at higher absorbed dose levels and downregulated at lower absorbed dose levels, suggesting different involvement of this signalling pathway at different absorbed dose levels. This was especially the case 24 h after 211At administration, but a similar trend was also seen after 131I administration. ILK signalling and radiation damage have been previously connected, and furthermore, ILK signalling partly controls cell adhesion and mediates prosurvival and antiapoptotic signalling after exposure to ionizing radiation [59]. Additionally, several cell adhesion GO terms were identified when performing in-depth separate analysis of the transcriptional response of thyroid tissue from animals in the three experiments that constitute the present study [20–22].

In the present study, the predicted upstream regulation of several peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), and PPAR ligands and agonists was found. The PPARs are of interest in the radiation-induced biological response. In one study, administration of the PPARα agonist fenofibrate prevented some cognitive function impairment in young rats exposed to 40 Gy fractionated whole-brain irradiation [60]. In another study, knockout of PPARα resulted in inhibition of radiation-induced apoptosis in the mouse kidney through regulation of Nfkb and anti-apoptosis factors [61]. Together, these results indicate that the PPAR network may play a role in radiation-induced biological response and that it may be targeted to modulate radiation damage in various tissues.

Conclusions

A profound effect on gene expression in mouse thyroid tissue after 131I and 211At exposure was detected, and 27 genes, of which many are associated with immune response, were identified as potential biomarkers for 131I and 211At exposure, and the biomarker applicability of these genes should be further studied. Hierarchical clustering revealed distinct differences between transcriptional profiles of both similar and different exposures, demonstrating the necessity for better understanding of radiation-induced changes in cellular activity. Additionally, the kallikrein network deserves further attention since literature shows how administration of protease inhibitors, known to decrease kallikrein levels, drastically increased survival in various irradiated species. An effect on thyroid cancer signalling was identified, as well as regulation of several genes previously identified as biomarkers for thyroid cancer; however, it is unlikely that thyroid cancer can be manifested at the transcriptional level at these early times after initiation of radiation exposure. Furthermore, the present study supports that ionizing radiation may impact calcium-related biological processes. Taken together, we consider RNA microarrays, especially in the in vivo setting, to be an important tool to gain further insight in the complex radiation-induced changes in cellular activity and affected pathways, and for biomarker discovery.

Compliance with ethical standards

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. The study design was approved by the Ethical Committee on Animal Experiments in Gothenburg, Sweden. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the European Commission FP7 Collaborative Project TARCC HEALTH-F2-2007-201962, the Swedish Research Council (grant no. 21073), the Swedish Cancer Society (grant no. 3427), BioCARE - a National Strategic Research Program at the University of Gothenburg, the Swedish Radiation Safety Authority, the King Gustav V Jubilee Clinic Cancer Research Foundation, the Sahlgrenska University Hospital Research Funds, and the Assar Gabrielsson Cancer Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

NR and EFA designed the animal studies. NR, ES, and TZP carried out the animal experiments. TZP, ES, and NR performed the extraction of RNA and preprocessing of the data. NR, KH, JS, ES, and BL performed the data analysis. All authors contributed to the scientific and intellectual discussion and interpretation of the results. NR drafted the manuscript, and all authors participated with substantial input and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, Kloos RT, Lee SL, Mandel SJ, et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines taskforce on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19(11):1167–214. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaminski MS, Tuck M, Estes J, Kolstad A, Ross CW, Zasadny K, et al. 131I-tositumomab therapy as initial treatment for follicular lymphoma. New Engl J Med. 2005;352(5):441–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bombardieri E, Giammarile F, Aktolun C, Baum RP, Delaloye AB, Maffioli L, et al. 131I/123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (mIBG) scintigraphy: procedure guidelines for tumour imaging. EJNMMI. 2010;37(12):2436–46. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1545-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid JR, Wheeler SF. Hyperthyroidism: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(4):623–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown I. Astatine-211: its possible applications in cancer therapy. Int J Rad Appl Instrum A. 1986;37(8):789–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Andersson H, Cederkrantz E, Back T, Divgi C, Elgqvist J, Himmelman J, et al. Intraperitoneal alpha-particle radioimmunotherapy of ovarian cancer patients: pharmacokinetics and dosimetry of (211)At-MX35 F(ab’)2--a phase I study. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(7):1153–60. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.062604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaidyanathan G, Zalutsky MR. Applications of 211At and 223Ra in targeted alpha-particle radiotherapy. Curr Radiopharm. 2011;4(4):283. doi: 10.2174/1874471011104040283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zalutsky MR, Reardon DA, Pozzi OR, Vaidyanathan G, Bigner DD. Targeted alpha-particle radiotherapy with 211At-labeled monoclonal antibodies. Nucl Med Biol. 2007;34(7):779–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spetz J, Rudqvist N, Forssell-Aronsson E. Biodistribution and dosimetry of free 211At, 125I− and 131I− in rats. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2013;28(9):657–64. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2013.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lundh C, Lindencrona U, Schmitt A, Nilsson M, Forssell-Aronsson E. Biodistribution of free 211At and 125I-in nude mice bearing tumors derived from anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2006;21(6):591–600. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2006.21.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindencrona U, Nilsson M, Forssell-Aronsson E. Similarities and differences between free 211 At and 125I− transport in porcine thyroid epithelial cells cultured in bicameral chambers. Nucl Med Biol. 2001;28(1):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Brans B, Monsieurs M, Laureys G, Kaufman JM, Thierens H, Dierckx RA. Thyroidal uptake and radiation dose after repetitive I-131-MIBG treatments: influence of potassium iodide for thyroid blocking. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38(1):41–6. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annex J. Exposures and effects of the Chernobyl accident. Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation: The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation UNSCEAR. 2000. pp. 451–566. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardis E, Kesminiene A, Ivanov V, Malakhova I, Shibata Y, Khrouch V, et al. Risk of thyroid cancer after exposure to 131I in childhood. JNCI. 2005;97(10):724–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danielsson A, Claesson K, Parris TZ, Helou K, Nemes S, Elmroth K, et al. Differential gene expression in human fibroblasts after alpha-particle emitter (211)At compared with (60)Co irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2013;89(4):250–8. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2013.746751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidl C, Port M, Apostolidis C, Bruchertseifer F, Schwaiger M, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, et al. Differential gene expression triggered by highly cytotoxic alpha-emitter-immunoconjugates in gastric cancer cells. Investig New Drugs. 2010;28(1):49–60. doi: 10.1007/s10637-008-9214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidl C, Port M, Gilbertz KP, Morgenstern A, Bruchertseifer F, Schwaiger M, et al. 213Bi-induced death of HSC45-M2 gastric cancer cells is characterized by G2 arrest and up-regulation of genes known to prevent apoptosis but induce necrosis and mitotic catastrophe. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(8):2346–59. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yong KJ, Milenic DE, Baidoo KE, Brechbiel MW. Impact of alpha-targeted radiation therapy on gene expression in a pre-clinical model for disseminated peritoneal disease when combined with paclitaxel. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e108511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yong KJ, Milenic DE, Baidoo KE, Kim YS, Brechbiel MW. Gene expression profiling upon (212) Pb-TCMC-trastuzumab treatment in the LS-174T i.p. xenograft model. Cancer Med. 2013;2(5):646–53. doi: 10.1002/cam4.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudqvist N, Parris TZ, Schuler E, Helou K, Forssell-Aronsson E. Transcriptional response of BALB/c mouse thyroids following in vivo astatine-211 exposure reveals distinct gene expression profiles. EJNMMI Res. 2012;2(1):32. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-2-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudqvist N, Schüler E, Parris TZ, Langen B, Helou K, Forssell-Aronsson E. Dose-specific transcriptional responses in thyroid tissue in mice after 131I administration. Nuclear Med and Biol. 2014; 42(3): 263-268. doi:10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Rudqvist N, Spetz J, Schüler E, Parris TZ, Langen B, Helou K, et al. Transcriptional response in mouse thyroid tissue after 211 at administration: effects of absorbed dose, initial dose-rate and time after administration. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0131686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schuler E, Parris TZ, Rudqvist N, Helou K, Forssell-Aronsson E. Effects of internal low-dose irradiation from 131I on gene expression in normal tissues in Balb/c mice. EJNMMI Res. 2011;1(1):29. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langen B, Rudqvist N, Parris TZ, Schuler E, Helou K, Forssell-Aronsson E. Comparative analysis of transcriptional gene regulation indicates similar physiologic response in mouse tissues at low absorbed doses from intravenously administered 211At. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(6):990–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.114462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langen B, Rudqvist N, Parris TZ, Schüler E, Spetz J, Helou K, et al. Transcriptional response in normal mouse tissues after iv 211At administration-response related to absorbed dose, dose rate, and time. EJNMMI Res. 2015;5(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13550-014-0078-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garg PK, Harrison CL, Zalutsky MR. Comparative tissue distribution in mice of the alpha-emitter 211At and 131I as labels of a monoclonal antibody and F(ab’)2 fragment. Cancer Res. 1990;50(12):3514–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flynn AA, Green AJ, Pedley RB, Boxer GM, Boden R, Begent RH. A mouse model for calculating the absorbed beta-particle dose from (131)I- and (90)Y-labeled immunoconjugates, including a method for dealing with heterogeneity in kidney and tumor. Radiat Res. 2001;156(1):28–35. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0028:AMMFCT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lance GN, Williams WT. A general theory of classificatory sorting strategies II. Clustering systems. Comput J. 1967;10(3):271–7. doi: 10.1093/comjnl/10.3.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuler E, Rudqvist N, Parris TZ, Langen B, Spetz J, Helou K, et al. Time- and dose rate-related effects of internal (177)Lu exposure on gene expression in mouse kidney tissue. Nucl Med Biol. 2014;41(10):825–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma M, Halligan BD, Wakim BT, Savin VJ, Cohen EP, Moulder JE. The urine proteome as a biomarker of radiation injury: submitted to proteomics- clinical applications special issue: “renal and urinary proteomics (Thongboonkerd)”. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2008;2(7–8):1065–86. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makoyo PO, West WL. Effect of focal irradiation on plasma kallikrein activity in tumor bearing rats. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2(9–10):945–8. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(77)90192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langen B. Systemic effects after ionizing radiation exposure: Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of mouse normal tissues exposed to (211) At,(131) I, or 4 MV photon beam: PhD thesis, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden. 2015.

- 33.Palladino MA, Galton JE, Troll W, Thorbecke GJ. Gamma-irradiation-induced mortality: protective effect of protease inhibitors in chickens and mice. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med. 1982;41(2):183–91. doi: 10.1080/09553008214550181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall-Glenn F, Lyons KM. Roles for CCN2 in normal physiological processes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(19):3209–17. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0782-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curie T, Mongrain V, Dorsaz S, Mang GM, Emmenegger Y, Franken P. Homeostatic and circadian contribution to EEG and molecular state variables of sleep regulation. Sleep. 2013;36(3):311–23. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun ZS, Albrecht U, Zhuchenko O, Bailey J, Eichele G, Lee CC. RIGUI, a putative mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila period gene. Cell. 1997;90(6):1003–11. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80366-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanchez L, Calvo M, Brock JH. Biological role of lactoferrin. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67(5):657–61. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.5.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Varadhachary A, Petrak K, Blezinger P, inventors; Google Patents, assignee . Lactoferrin as a radioprotective agent. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muller K, Meineke V. Radiation-induced mast cell mediators differentially modulate chemokine release from dermal fibroblasts. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;61(3):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mallya M, Campbell RD, Aguado B. Transcriptional analysis of a novel cluster of LY-6 family members in the human and mouse major histocompatibility complex: five genes with many splice forms. Genomics. 2002;80(1):113–23. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gebhardt C, Nemeth J, Angel P, Hess J. S100A8 and S100A9 in inflammation and cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72(11):1622–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith DJ, Salmi M, Bono P, Hellman J, Leu T, Jalkanen S. Cloning of vascular adhesion protein 1 reveals a novel multifunctional adhesion molecule. J Exp Med. 1998;188(1):17–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perrotta C, Buldorini M, Assi E, Cazzato D, De Palma C, Clementi E, et al. The thyroid hormone triiodothyronine controls macrophage maturation and functions: protective role during inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2014;184(1):230–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlyle JR, Jamieson AM, Gasser S, Clingan CS, Arase H, Raulet DH. Missing self-recognition of Ocil/Clr-b by inhibitory NKR-P1 natural killer cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(10):3527–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308304101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pejler G, Knight SD, Henningsson F, Wernersson S. Novel insights into the biological function of mast cell carboxypeptidase A. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(8):401–8. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaly Y, Fu Y, Marinov A, Hostager B, Yan W, Campfield B, et al. Follistatin-like protein 1 enhances NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1beta secretion from monocytes and macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44(5):1467–79. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han HJ, Tokino T, Nakamura Y. CSR, a scavenger receptor-like protein with a protective role against cellular damage causedby UV irradiation and oxidative stress. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(6):1039–46. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schuler E. Biomarker discovery and assessment for prediction of kidney response after 177Lu-octreotate therapy. PhD thesis, Department of Radiation Physics, Institution of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg. 2014.

- 49.Rudqvist N. Radiobiological effects of the thyroid gland: Transcriptomic and proteomic responses to 131I and 211At exposure: PhD thesis, Department of Radiation Physics, Institution of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2015.

- 50.Cerutti JM, Oler G, Delcelo R, Gerardt R, Michaluart P, Jr, de Souza SJ, et al. PVALB, a new Hurthle adenoma diagnostic marker identified through gene expression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):E151–E60. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giordano TJ, Au AY, Kuick R, Thomas DG, Rhodes DR, Wilhelm KG, et al. Delineation, functional validation, and bioinformatic evaluation of gene expression in thyroid follicular carcinomas with the PAX8-PPARG translocation. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(7):1983–93. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cui L, Zhang Q, Mao Z, Chen J, Wang X, Qu J, et al. CTGF is overexpressed in papillary thyroid carcinoma and promotes the growth of papillary thyroid cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2011;32(4):721–8. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ito Y, Arai K, Nozawa R, Yoshida H, Hirokawa M, Fukushima M, et al. S100A8 and S100A9 expression is a crucial factor for dedifferentiation in thyroid carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(10):4157–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parris TZ, Kovacs A, Aziz L, Hajizadeh S, Nemes S, Semaan M, et al. Additive effect of the AZGP1, PIP, S100A8 and UBE2C molecular biomarkers improves outcome prediction in breast carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(7):1617–29. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kukita A, Bonewald L, Rosen D, Seyedin S, Mundy GR, Roodman GD. Osteoinductive factor inhibits formation of human osteoclast-like cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(8):3023–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hu YS, Zhou H, Myers D, Quinn JM, Atkins GJ, Ly C, et al. Isolation of a human homolog of osteoclast inhibitory lectin that inhibits the formation and function of osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(1):89–99. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0301215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lyng FM, Maguire P, McClean B, Seymour C, Mothersill C. The involvement of calcium and MAP kinase signaling pathways in the production of radiation-induced bystander effects. Radiat Res. 2006;165(4):400–9. doi: 10.1667/RR3527.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paul S, Ghandhi SA, Weber W, Doyle-Eisele M, Melo D, Guilmette R, et al. Gene expression response of mice after a single dose of 137CS as an internal emitter. Radiat Res. 2014;182(4):380–9. doi: 10.1667/RR13466.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cordes N. Overexpression of hyperactive integrin-linked kinase leads to increased cellular radiosensitivity. Cancer Res. 2004;64(16):5683–92. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greene-Schloesser D, Payne V, Peiffer AM, Hsu FC, Riddle DR, Zhao W, et al. The peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha agonist, fenofibrate, prevents fractionated whole-brain irradiation-induced cognitive impairment. Radiat Res. 2014;181(1):33–44. doi: 10.1667/RR13202.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao W, Iskandar S, Kooshki M, Sharpe JG, Payne V, Robbins ME. Knocking out peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha inhibits radiation-induced apoptosis in the mouse kidney through activation of NF-kappaB and increased expression of IAPs. Radiat Res. 2007;167(5):581–91. doi: 10.1667/RR0814.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]