Abstract

[Purpose] Multidisciplinary treatments are recommended for treatment of chronic low back pain. The aim of this study was to show the associations among multidisciplinary treatment outcomes, pretreatment psychological factors, self-reported pain levels, and history of pain in chronic low back pain patients. [Subjects and Methods] A total of 221 chronic low back pain patients were chosen for the study. The pretreatment scores for the 10-cm Visual Analogue Scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Pain Catastrophizing Scale, Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire, Pain Disability Assessment Scale, pain drawings, and history of pain were collected. The patients were divided into two treatment outcome groups a year later: a good outcome group and a poor outcome group. [Results] One-hundred eighteen patients were allocated to the good outcome group. The scores for the Visual Analogue Scale, Pain Disability Assessment Scale, and affective subscale of the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire and number of nonorganic pain drawings in the good outcome group were significantly lower than those in the poor outcome group. Duration of pain in the good outcome group was significantly shorter than in the poor outcome group. [Conclusion] These findings help better predict the efficacy of multidisciplinary treatments in chronic low back pain patients.

Key words: Chronic pain, Low back pain, Multidisciplinary treatments

INTRODUCTION

Chronic low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common long-term health problems in adults in many countries. The prevalence of LBP in previous studies ranged from 18.6% to 57.4%1,2,3,4,5). Investigation of chronic pain, including chronic LBP, has shifted from a purely biomedical model to a more holistic, biopsychosocial one6). There is strong evidence indicating that intensive multidisciplinary biopsychosocial treatments with a functional restoration approach have improved function when compared with inpatient or outpatient non-multidisciplinary treatments7). Moreover, current guidelines generally advocate the use of multidisciplinary cognitive-behavioral and exercise rehabilitation programs as first-line treatments8). However, it has been difficult for clinicians to confirm efficacy, because chronic LBP is a complex, heterogeneous medical condition that includes a wide variety of symptoms9). Some studies showed associations of treatment outcome with patient characteristics, patient history, and psychological disturbance in chronic pain10,11,12,13). Therefore, further assessment of treatments for chronic LBP patients has been needed.

Our center is the first multidisciplinary pain center in Japan and was established in July 2007. To date, there have been no reports of the effects of multidisciplinary treatments on LBP in Japan. The purpose of this research was to show the associations among multidisciplinary treatment outcomes, pretreatment psychological factors, self-reported pain levels, and history of pain in chronic LBP patients.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

We included a total of 221 chronic LBP patients who visited the Pain Center of Aichi Medical University between January 2010 and December 2011. Chronic LBP is defined as back symptoms persisting for at least 3 months11). Our Pain Center has anesthesiologists, orthopedists, psychiatrists, internists, dentists, nurses, physical therapists, and clinical psychotherapists. All patients were referred from other medical institutions. Upon presentation at our Pain Center for their first visit, the following data were collected for all patients: a set of standardized self-report measures, demographics, symptoms, duration of pain, education, and work status. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from self-reported height and self-reported weight by a nurse. Education status was divided into three categories (junior high school, high school, and college). Work status was also divided into three categories (working, sick leave, and unemployed). These data were extracted from medical records after approval from the Ethics Committee of Aichi Medical University.

The 10-cm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (0 = no pain; 10 = worst pain imaginable) was used to obtain the average intensity of total pain. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was designed to assess two separate dimensions of anxiety and depression. The HADS consists of 14 items, with the anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) subscales each including 7 items. A four-point response scale (from 0, representing absence of symptoms, to 3, representing maximum symptoms) was used, with possible scores for each subscale ranging from 0 to 2114, 15). The HADS is designed to avoid the use of somatic symptoms that may confound other self-report measures of depression and anxiety14, 15). The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) consists of 13 items, and subjects rate how frequently they have experienced such cognition/emotions16, 17). The PCS is composed of three subscales: rumination (e.g., “I keep thinking about how much it hurts”), magnification (e.g., “I wonder whether something serious may happen”), and helplessness (e.g., “There is nothing I can do to reduce the intensity of the pain”)16, 17). The total score of the PCS can range from 0 to 5216, 17). The number of subjects who completed the PCS (n=101) was less than the number of subjected who completed the other self-report measures (n=221), as we have only recently begun to record it in our daily clinical practice. The Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) is comprised of 15 descriptors of pain and two scales for rating pain intensity18). It is scored by summarizing all words used to describe pain (0–15) and by counting the intensity assigned to each word18). The sensory subscale of the SF-MPQ includes descriptors 1–11, while descriptors 12–15 represent affective interpretations18). The total score of the SF-MPQ ranged from 0 to 4518). The Pain Disability Assessment Scale (PDAS) assesses the degree to which chronic pain interfered with various daily activities during the past week19). It includes 20 items reflecting pain interference in a broad range of daily activities, and respondents indicate the extent to which pain interfered with activities19). Scores for the total PDAS range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating higher levels of pain interference19). Pain drawings are commonly used to describe the location of pain reported by a patient. The pain drawings were classified according to the principles described in several previous studies20,21,22), and scored with the nonorganic pain drawing scale on a scale of 1 to 4: 1 = organic; 2 = possibly organic; 3 = possibly nonorganic; 4 = nonorganic. The first author scored all pain drawings. Our previous study confirmed extremely high inter-rater agreement regarding the four classifications of the pain drawings20). For ease of use, the organic and possibly organic drawings were pooled into an “organic” group, and those classified as nonorganic or possibly nonorganic were pooled into a “nonorganic” group as previously described20, 23, 24).

We administered treatment after a medical conference attended by different types of professionals. As required, we administered pharmacological (including Kampo medicine, traditional Japanese herbal medicine25)), physical, acupuncture, cognitive-behavioral, and psychological treatments. Multidisciplinary treatment was based on the biopsychosocial model of illness focusing on the operant and cognitive-behavioral approach. The duration of treatment ranged from half an hour to an hour per visit. The frequency of visits ranged from 1 to 2 times per month. We excluded patients who had undergone surgery during the treatment period. Almost all patients were followed up a year later, at which time we recorded the VAS score. Data other than the VAS score were not recorded routinely in our daily clinical practice. We classified patients into two groups: a good outcome group, for patients whose pain level decreased by at least 50% according to the VAS score compared with before treatment, and a poor outcome group for patients whose pain level did not26,27,28,29).

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean (SD). The data were analyzed using the PASW Statistics software (version 18.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). The χ2 test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient test were used for statistical analysis. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

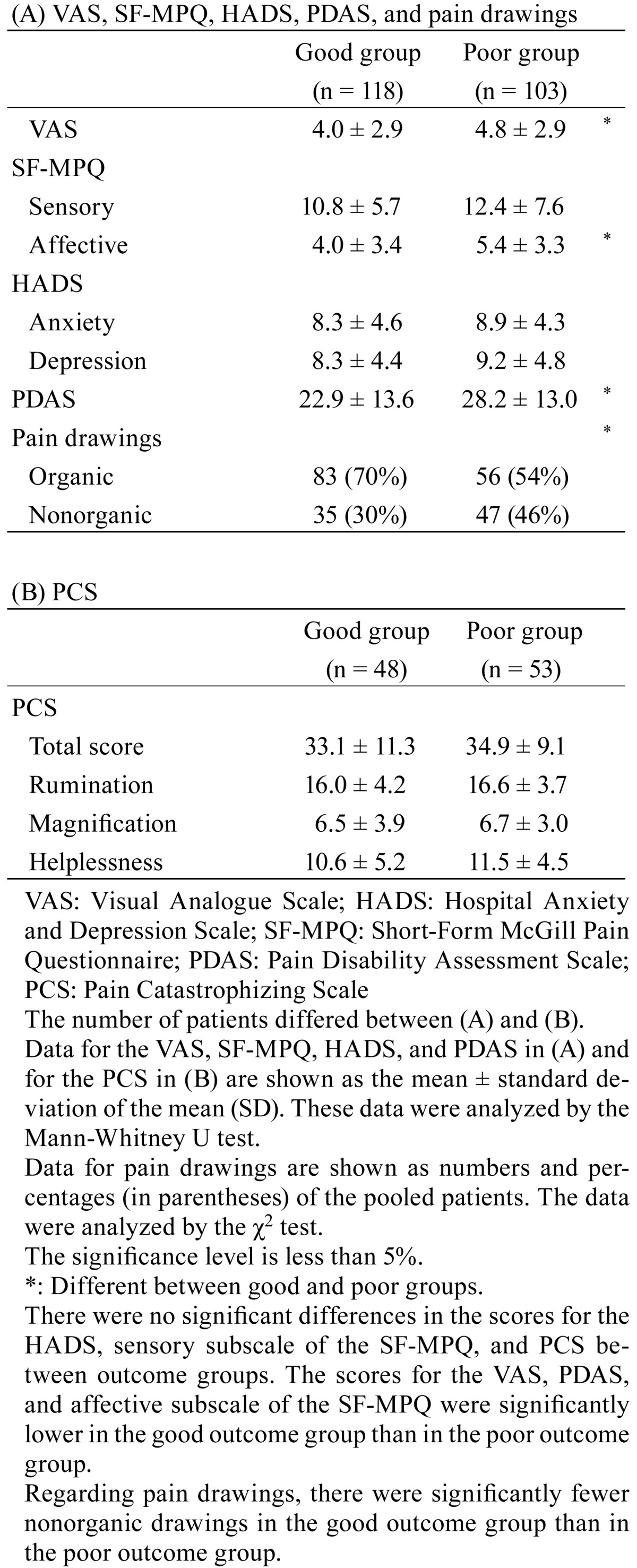

One-hundred eighteen patients (53.3%) were divided into the good outcome group, and 103 patients (46.7%) were divided into the poor outcome group. There were no significant differences in patient characteristics or daily life factors between the good outcome and poor outcome groups (Table 1). As shown in Table 2 , the pretreatment scores for the VAS, HADS, PCS, SF-MPQ, PDAS, and pain drawings were compared between the outcome groups. Fewer subjects completed the PCS compared with the other self-report measures (Table 2). The HADS, sensory subscale of the SF-MPQ, and PCS scores did not show significant differences between the groups. On the other hand, the VAS, PDAS, and affective subscale of the SF-MPQ showed significantly lower scores in the good outcome group compared with the poor outcome group. Regarding the pain drawings, there were significantly fewer nonorganic pain drawings in the good outcome group (n=35/118) than in the poor outcome group (n=47/103). As shown in Table 3, characteristics of daily pain were investigated between the two outcome groups. The results showed that the number of patients who experienced pain at night in the good outcome group (n=25/118) was significantly lower than that in the poor outcome group (n=36/103). Furthemore, the number of patients who experienced pain in the morning in the good outcome group (n=33/118) was significantly greater than that in the poor outcome group (n=17/103). As shown in Table 4, the duration of pain in the good outcome group was significantly shorter than in the poor outcome group. The other items in the course of development of pain did not show significant differences between the two outcome groups (Table 4).

Table 1. Comparison of patient characteristics and daily life factors.

| Good group | Poor group | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 118) | (n = 103) | |

| Age | 56.8 ± 16.7 | 58.1 ± 14.6 |

| BMI | 22.3 ± 3.3 | 22.4 ± 3.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 71 (60%) | 67 (65%) |

| Female | 47 (40%) | 36 (35%) |

| Education history | ||

| Junior high school | 22 (19%) | 18 (17%) |

| High school | 48 (41%) | 52 (51%) |

| College | 39 (33%) | 28 (27%) |

| No data | 9 (7%) | 5 (5%) |

| Work | ||

| Working | 43 (36%) | 33 (32%) |

| Sick leave | 13 (11%) | 14 (14%) |

| Unemployment | 62 (53%) | 56 (54%) |

| Sleep disorder | ||

| + | 92 (78%) | 81 (79%) |

| − | 26 (22%) | 22 (21%) |

| Drinking habit | ||

| + | 32 (27%) | 28 (27%) |

| − | 86 (73%) | 75 (73%) |

| Smoking habit | ||

| + | 10 ( 8%) | 11 (11%) |

| − | 108 (92%) | 92 (89%) |

| Exercising habit | ||

| + | 65 (55%) | 57 (55%) |

| − | 53 (45%) | 46 (45%) |

BMI: body mass index. Data for gender, education history, work, sleep disorder, drinking habit, smoking habit, and exercising habit are shown as numbers and percentages (in parentheses) of patients who replied subjectively with “yes.” These data were analyzed by the χ2 test. Data for age and BMI are shown as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean (SD). These data were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. The significance level is less than 5%. There were no significant differences in patient characteristics and daily life factors between outcome groups.

Table 2. Comparison of pretreatment scores for self-report measures between outcome groups.

Table 3. . Characteristic of daily pain.

| Good group (n = 118) |

Poor group (n = 103) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain at rest | |||

| + | 77 (65%) | 79 (77%) | |

| − | 41 (35%) | 24 (23%) | |

| Pain during motion | |||

| + | 61 (52%) | 53 (51%) | |

| − | 57 (48%) | 50 (49%) | |

| Painful to the touch | |||

| + | 14 (12%) | 16 (16%) | |

| − | 104 (88%) | 87 (84%) | |

| Pain changing with the weather | |||

| + | 91 (77%) | 77 (75%) | |

| − | 27 (23%) | 26 (25%) | |

| Painful at night | * | ||

| + | 25 (21%) | 36 (35%) | |

| − | 93 (79%) | 67 (65%) | |

| Painful in the morning | * | ||

| + | 33 (28%) | 17 (17%) | |

| − | 85 (72%) | 86 (83%) | |

| Pain reduced in daytime | |||

| + | 11 ( 9%) | 6 ( 6%) | |

| − | 107 (91%) | 97 (94%) | |

| Pain unaltered during day | |||

| + | 45 (38%) | 47 (46%) | |

| − | 73 (62%) | 56 (54%) | |

| Pain changing during day | |||

| + | 55 (47%) | 46 (45%) | |

| − | 63 (53%) | 57 (55%) |

Data for paint at rest, pain during motion, painful to the touch, pain changing with the weather, painful at night, painful in the morning, pain reduced in daytime, pain unaltered during day, and pain changing during day are shown as numbers and percentages (in parentheses) of patients who replied subjectively with “yes.” These data were analyzed by the χ2 test. The significance level is less than 5%. *: Different between good and poor groups. There were significantly fewer patients reporting painful at night in the good outcome group than the poor outcome group. There were significantly more patients reporting painful in the morning in the good outcome group than the poor outcome group. There were no significant differences for the other characteristics between the outcome groups.

Table 4. Course of development of pain.

| Good group |

Poor group (n = 103) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of pain (y) | * | ||

| <1 | 45 (38%) | 24 (23%) | |

| ≥1 | 73 (62%) | 79 (77%) | |

| Pain development | |||

| By gradation) | 66 (56% | 67 (65%) | |

| Rapidly | 52 (44%) | 36 (35%) | |

| Cause of injury | |||

| Traffic accident | 7 ( 6%) | 9 ( 9%) | |

| Work-related injury | 1 ( 1%) | 2 ( 2%) | |

| Unclear | 110 (93%) | 92 (89%) |

Data for duration of pain, pain development, and cause of injury are shown as numbers and percentages (in parentheses) of patients who replied subjectively with “yes.” These data were analyzed by the χ2 test. The significance level is less than 5%. *: Different between good and poor groups. The durations of pain in the good outcome group were significantly shorter than those in the poor outcome group. There were no significant differences in the other items concerning the course of development of pain between the outcome groups.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the pretreatment scores for the VAS, PDAS, affective subscale of the SF-MPQ, and pain drawings were associated with outcomes in the chronic LBP patients. Pretreatment status predicted treatment outcome in chronic pain patients10,11,12,13). This is the first report to show the association between the PDAS and multidisciplinary treatment outcomes. The PDAS reflects pain interference in a broad range of daily activities, and respondents indicate the extent to which pain interferes with activities19). This might help us better predict the efficacy of multidisciplinary treatments in chronic LBP patients.

The results regarding the characteristics of daily pain revealed that the number of patients who experienced pain at night and the number of patients who experienced pain in the morning were significantly lower and higher, respectively, in the good outcome group than in the poor outcome group. These findings suggest that the patients who got progressively worse during the day had poor outcomes. The findings indicated that assessment of chronic LBP patients could require not only psychological questionnaires but also standard medical interviews.

The pretreatment scores for catastrophizing were not consistently associated with the outcomes. In previous systematic reviews of nonspecific chronic LBP, although a decrease in catastrophizing was accompanied by an increase in daily activities and a decrease in pain levels, pretreatment scores for catastrophizing were not consistently associated with outcomes30).

There were several limitations in this study. The multidisciplinary treatments offered in this study differed from the norm of offering 1–2 sessions per week for 6–12 consecutive weeks7). However, 53.3% of the patients were in the good outcome group in the present study, which was not much different from the rates in previous studies28, 31,32,33). In addition, physical function and quality of life were not investigated after treatment in the present study. The treatment goals for the chronic pain patients were not only pain intensity. Further studies are needed using multidimensional outcomes. This study included only a small number of patients from a single medical center. Furthermore, the number of the subjects assessed with the PCS, was particularly small in the present study. The results of the present study must be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, poor outcomes were related to high pretreatment scores for the VAS, PDAS, and affective subscale of the SF-MPQ; nonorganic pain drawings; longer duration of pain; and pain that progressively worsened for days in chronic LBP patients who received multidisciplinary treatments for a year.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. : A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum, 2012, 64: 2028–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kai S: Consideration of low back pain in health and welfare workers. J Phys Ther Sci, 2001, 13: 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung SH, Her JG, Ko T, et al. : Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Korean physical therapists. J Phys Ther Sci, 2013, 25: 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alghadir A, Zafar H, Iqbal ZA: Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals in Saudi Arabia. J Phys Ther Sci, 2015, 27: 1107–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mainenti MR, Felicio LR, Rodrigues EC, et al. : Pain, work-related characteristics, and psychosocial factors among computer workers at a university center. J Phys Ther Sci, 2014, 26: 567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shavers VL, Bakos A, Sheppard VB: Race, ethnicity, and pain among the U.S. adult population. J Health Care Poor Underserved, 2010, 21: 177–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. : Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2014, 9: CD000963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al. COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain: Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J, 2006, 15: S192–S300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanova JI, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, et al. : Real-world practice patterns, health-care utilization, and costs in patients with low back pain: the long road to guideline-concordant care. Spine J, 2011, 11: 622–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, et al. : A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine, 2002, 27: E109–E120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Hooff ML, Spruit M, O’Dowd JK, et al. : Predictive factors for successful clinical outcome 1 year after an intensive combined physical and psychological programme for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J, 2014, 23: 102–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Hulst M, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, Ijzerman MJ: A systematic review of sociodemographic, physical, and psychological predictors of multidisciplinary rehabilitation-or, back school treatment outcome in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine, 2005, 30: 813–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCracken LM, Turk DC: Behavioral and cognitive-behavioral treatment for chronic pain: outcome, predictors of outcome, and treatment process. Spine, 2002, 27: 2564–2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pallant JF, Bailey CM: Assessment of the structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in musculoskeletal patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2005, 3: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsudaira T, Igarashi H, Kikuchi H, et al. : Factor structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in Japanese psychiatric outpatient and student populations. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2009, 7: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J: The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol Assess, 1995, 7: 524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuoka H, Sakano Y: Assessment of cognitive aspect of pain: development, reliability, and validation of Japanese version of Pain Catastrophizing Scale. Jpn J Psychosom Med, 2007, 47: 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beattie PF, Dowda M, Feuerstein M: Differentiating sensory and affective-sensory pain descriptions in patients undergoing magnetic resonance imaging for persistent low back pain. Pain, 2004, 110: 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamashiro K, Arimura T, Iwaki R, et al. : A multidimensional measure of pain interference: reliability and validity of the pain disability assessment scale. Clin J Pain, 2011, 27: 338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi K, Arai YC, Morimoto A, et al. : Associations between pain drawing and psychological characteristics of different body region pains. Pain Pract, 2015, 15: 300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahl B, Gehrchen PM, Kiaer T, et al. : Nonorganic pain drawings are associated with low psychological scores on the preoperative SF-36 questionnaire in patients with chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J, 2001, 10: 211–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mann NH, 3rd, Brown MD, Hertz DB, et al. : Initial-impression diagnosis using low-back pain patient pain drawings. Spine, 1993, 18: 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Udén A, Aström M, Bergenudd H: Pain drawings in chronic back pain. Spine, 1988, 13: 389–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan CW, Goldman S, Ilstrup DM, et al. : The pain drawing and Waddell’s nonorganic physical signs in chronic low-back pain. Spine, 1993, 18: 1717–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arai YC, Yasui H, Isai H, et al. : The review of innovative integration of Kampo medicine and Western medicine as personalized medicine at the first multidisciplinary pain center in Japan. EPMA J, 2014, 5: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunreben-Stempfle B, Griessinger N, Lang E, et al. : Effectiveness of an intensive multidisciplinary headache treatment program. Headache, 2009, 49: 990–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hägg O, Fritzell P, Hedlund R, et al. Swedish Lumbar Spine Study: Pain-drawing does not predict the outcome of fusion surgery for chronic low-back pain: a report from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study. Eur Spine J, 2003, 12: 2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burchiel KJ, Anderson VC, Wilson BJ, et al. : Prognostic factors of spinal cord stimulation for chronic back and leg pain. Neurosurgery, 1995, 36: 1101–1110, discussion 1110–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poulsen DL, Hansen HJ, Langemark M, et al. : Discomfort or disability in patients with chronic pain syndrome. Psychother Psychosom, 1987, 48: 60–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wertli MM, Burgstaller JM, Weiser S, et al. : Influence of catastrophizing on treatment outcome in patients with nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Spine, 2014, 39: 263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott W, Wideman TH, Sullivan MJ: Clinically meaningful scores on pain catastrophizing before and after multidisciplinary rehabilitation: a prospective study of individuals with subacute pain after whiplash injury. Clin J Pain, 2014, 30: 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lanes TC, Gauron EF, Spratt KF, et al. : Long-term follow-up of patients with chronic back pain treated in a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program. Spine, 1995, 20: 801–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Workman EA, Hubbard JR, Felker BL: Comorbid psychiatric disorders and predictors of pain management program success in patients with chronic pain. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry, 2002, 4: 137–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]