Abstract

The objective of this study is to estimate the prevalence, treatment, and control of high blood pressure, hypertension (HBP) in Panama and assess its associations with sociodemographic and biologic factors.

A cross-sectional, descriptive study was conducted in Panama by administering a survey on cardiovascular risk factors to 3590 adults and measuring their blood pressure 3 times. A single-stage, probabilistic, and randomized sampling strategy with a multivariate stratification was used. The average blood pressure, confidence intervals (CIs), odds ratio (OR), and a value of P ≤ 0.05 were used for the analysis.

The estimated prevalence of HBP was 29.6% (95% CI, 28.0–31.1); it was more prevalent in men than in women, OR = 1.37 (95% CI, 1.17–1.61); it increased with age and was more frequent among Afro-Panamanians (33.8%). HBP was associated with a family history of HBP with being physically inactive and a body mass index ≥25.0 kg/m2 or a waist circumference >90 cm in men and >88 cm in women (P < 0.001). Of those found to have HBP, 65.6% were aware of having HBP and taking medications, and of these, 47.2% had achieved control (<140/90 mm Hg).

HBP is the most common cardiovascular risk factor among Panamanians and consequently an important public health problem in Panama. The health care system needs to give a high priority to HBP prevention programs and integrated care programs aimed at treating HBP, taking into consideration the changes in behavior that have been brought about by alterations in nutrition and sedentary lifestyles.

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiologic and health indicators show that in Latin America cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) have become the main causes of death.1,2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), CVD will be the leading cause of death and disability in the world by 2020. The number of victims worldwide from CVD is expected to increase to 20 million/y and this figure probably will rise to >24 million deaths by 2030.3 Panama’s National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC) estimated in 2012 that CVD accounted for 26.9% (4667/17350) of all medically certified deaths in the country that year.4

High blood pressure, hypertension (HBP) is one of the major modifiable risk factors for CVD, more specifically, for diseases such as heart failure, kidney failure, stroke, myocardial infarction, and acute coronary syndromes.3,5–8 The treatment and control of HBP is also one of the most effective public health interventions to prevent CVD and premature cardiovascular death.2,3

Until 2012, there were no population surveys in Panama that could be used to estimate the prevalence of HBP. The 2011 Survey on Risk Factors Associated With Cardiovascular Disease (PREFREC for its acronym in Spanish) is the first study done in Panama where biologic measurements of CVD risk factors, such as blood pressure (BP), lipid levels, and blood glucose levels, were obtained from a large sample of urban, rural, and indigenous communities of Panamanians.9

The aim of this article is to report on the prevalence, treatment, and control of HBP in Panama and also assess its associations with sociodemographic and biologic factors.

METHODS

Research Design and Area of Study

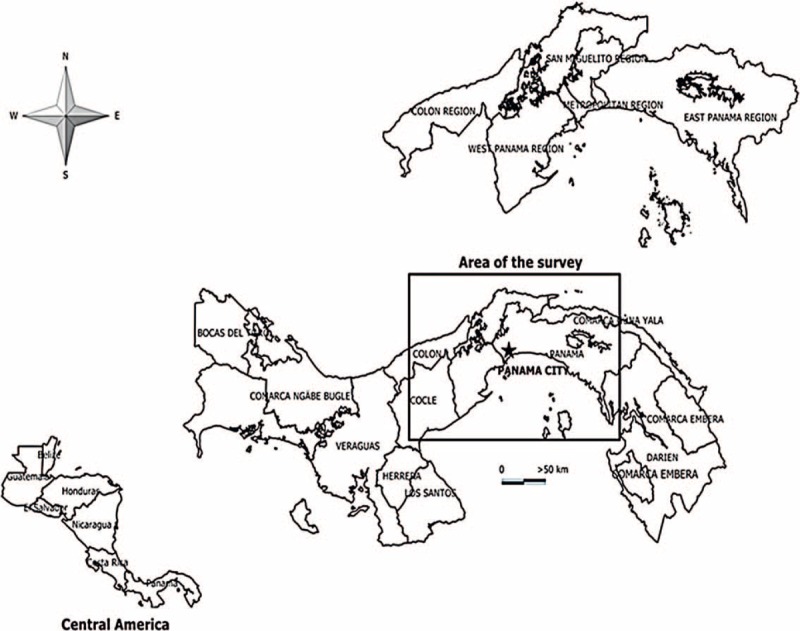

PREFREC was a cross-sectional, descriptive study conducted by the Gorgas Memorial Institute of Health Research (GMI) and the Panamanian Ministry of Health (MOH) in the transisthmian zone of the Republic of Panama. The study area encompassed the provinces of Panama, Colon, and the Madugandí Guna Comarca (formerly called Kuna Madugandí). This area contains Panama City, the capital of Panama (metropolitan health region), and the health regions of Western Panama, San Miguelito, East Panama, and Colon where 60.4% of all Panamanians 18 years or older reside. Panama is located at the southernmost end of Central America (see Figure 1) and has a population approximately of 3,800,000 inhabitants.10,11

FIGURE 1.

Republic of Panama. Political and administrative divisions.

Study Sample

We sampled houses, employing a single-stage, probabilistic, and randomized sampling strategy with a multivariate stratification that was developed by the INEC. This sampling strategy was carried out separately for urban, rural, and indigenous areas, based on maps produced by the year 2000 National Census of Panama. The sample was stratified according to the education level of the study population. A total of 3590 individuals aged 18 years and older who agreed to participate in the study (maximum 2 adults/household) were evaluated from the sampled houses. Pregnant women, people with body mass index (BMI) <18.5 Kg/m2, and individuals for whom measurements of BMI, waist circumference, and BP could not be obtained were excluded from the analysis. These exclusions reduced the sample size to 3406.

Individuals identified as having HBP were those who, at the time of the survey, were taking antihypertensive medications and/or people who had an average systolic blood pressure (SBP) of ≥140 mm Hg and/or an average diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of ≥90 mm Hg.12 Individuals with HBP who reported a history of physician-diagnosed HBP were classified as being aware of having HBP. Those who were taking antihypertensive medication and had an SBP measurement <40 mm Hg and an DBP measurement <90 mm Hg were classified as controlled, and those who had an SBP measurement ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg were classified as not under control.12 Individuals who had SBP measurements ≥140 mm Hg and/or DBP ≥90 mm Hg but not a reported history of HBP were classified as having HBP unawareness.

Biologic and Socioeconomic Variables

Age was defined as the years from the time of the individual’s birth until the day the survey was conducted; sex was defined by the phenotypical characteristics that distinguish men from women; area was defined by the geographic domain where the respondent usually lives (urban, rural, or indigenous); schooling was defined as the highest level of education attained by the participant be it primary, secondary, university, or postgraduate education; marital status was defined as being single, married, civil union, separated, divorced, or widowed; ethnic group was defined by the participant’s self identification as an Afro-Panamanian (Panamanian of African descent), Mestizo, white, native American (Amerindian), or of Asian descent. The monthly family income was defined as the total amount of United States dollars (USD) received by the family of the participant every month.

The BMI was calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the height in square meters (kg/m2) and categorized into 3 mutually exclusive groups based on WHO and NCEP-ATP III (the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program, Adult Treatment Panel III) criteria.13 Underweight was defined as a BMI of <18.5 kg/m2, normal weight was defined as a BMI of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, overweight was defined as a BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2, and obesity was defined as a BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Abdominal obesity in women was defined as a waist circumference >88 cm and in men >90 cm.14–16

Any sport, exercise, or activity that required energy expenditure associated with aerobic work was considered as physical activity. Those who engaged in <60 min/wk of physical activity were considered as physically inactive, those who engaged in physical activity lasting 60 to 149 min/wk were considered as having insufficient physical activity, and those who engaged in >150 min/wk of physical activity were considered physically active.

Data Collection Instruments and Procedures

The data collection instrument was a structured form (survey), developed by researchers from GMI, specialists from the Department of Chronic Diseases of the MOH, and representatives of the Pan American Health Organization in Panama. The planning process for the study included a pilot survey test that served to evaluate the methodology, procedures, instruments, and the organization of the fieldwork, and reduce errors and the risk of bias during the survey. Nationally recognized specialists in the fields of endocrinology, cardiology, and public health also validated the instrument.

University graduates and students in their final year of health sciences education were trained in interviewing and survey management to standardize the data collection process. In the indigenous areas, interpreters who spoke the indigenous dialect supported the people who administered the survey.

BP Measurement

The measurement of BP was performed with calibrated automatic sphygmomanometers made by American Diagnostic Corporation model 6013, which had cuff sizes for people with normal weight and for people who were obese. Before starting the fieldwork, the measurements of the automatic sphygmomanometers were validated with aneroid sphygmomanometers. All interviewers were trained in the handling and proper use and care of the equipment, procedure for BP measurement, and use of the appropriate cuff size for people with obesity.17

Three BP measurements were made in the right arm of each person with the participant seated and with a minimum of 5 minutes between the start of the survey and the first measurement, and between the second and third measurements.17 An average of these 3 BPs was used to define the participant’s BP. The classification of HBP according to the seventh report of JNC VII, the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure 2003 was used.12,18

The National Bioethics Committee of the Republic of Panama approved the study. All participants were informed about the objectives of the study, and they signed an informed consent.

Analysis Plan

The prevalence estimates from the study sample were calculated as percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For area, age, sociodemographic, and biological variables, odds ratio (OR) and P values were calculated using 2 × 2 tables for subjects with HBP and without HBP. For all cases, a value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.19,20

The data were processed using SPSS (version 19) (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL), Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Washington DC), and Epi Info, version 3.5.1 (Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA).

RESULTS

General Characteristics

A total of 3406 adults aged 18 years and older were studied of which 1034 were men (30.4%) and 2372 were women (69.6%). The average age of the study subjects was 46 years (48 for men, 44 for women), and the median age was 45 years (49 for men, 43 for women).

Prevalence of HBP by Sex, Age, and Area of Residence

BP values ≥140/90 mm Hg were found in 24.5% (836/3406) of the study subjects; among men, the prevalence was 33.5% (346/1034) and among women, 20.7% (490/2372). Of the total sample, 19.4% (661/3406) were receiving antihypertensive medicines; among men, the prevalence was 18.0% (186/1034) and among women, 20.0% (475/2372).

Of those found to have BP values ≥140/90 mm, 41.3% (345/836) were unaware of being hypertensive, of which 48.7% (168/345) were men and 51.3% (177/345) women.

The sum of those who were taking antihypertensive medication and those unaware of being hypertensive totaled 29.6% (1007/3406); this prevalence was 34.2% (354/1034) among men and 27.5% (653/2372) among women, OR = 1.37 (95% CI, 1.17–1.61), P < 0.001.

With increasing age, the prevalence of HBP also increased, and it was higher among those 60 years or older than among those <60 years of age, OR = 4.65 (95% CI, 3.90–5.54), P < 0.001. Being 50 years or older was associated with HBP for women, OR = 5.96 (95% CI, 4.89–7.25), P < 0.001, and this was also the case for men, OR = 3.29 (95% CI, 2.51–4.32), P < 0.001. Overall, HBP tended to be higher among men <50 years of age than among women of the same age group, OR = 1.46 (95% CI, 1.19–1.79), P = 0.001; among those 60 years or older, the prevalence tended to be higher in women than in men, OR = 1.35 (95% CI, 0.99–1.83), P = 0.06 (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of HBP (adjusted rates) according to age group and sex. HBP = high blood pressure, hypertension, PREFREC = Survey on Risk Factors Associated With Cardiovascular Disease. Source: PREFREC, 2010–2011.9

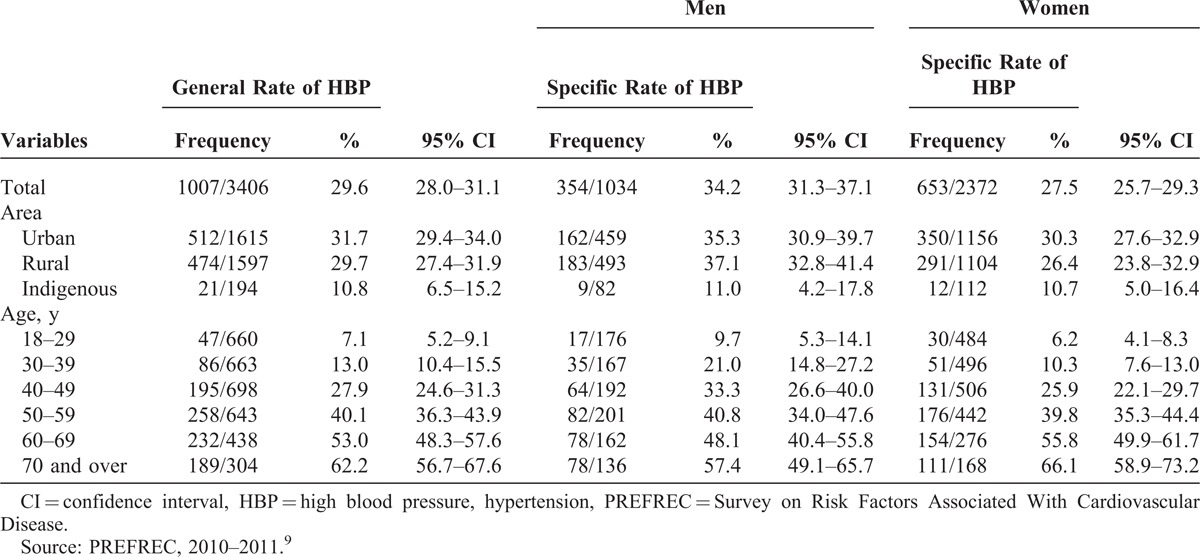

Those who lived in urban areas had a prevalence of HBP of 31.7% (512/1615; 95% CI, 29.4–34.0), whereas those who lived in indigenous areas had a prevalence of 10.8% (21/194; 95% CI, 6.5–15.2) (see Table 1). Furthermore, living in an urban or rural area was associated with a higher HBP prevalence than living in an indigenous area, OR = 3.65 (95% CI, 2.31–5.77), P < 0.001 (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

General and Specific Rates of HBP by Sex According to Area and Age

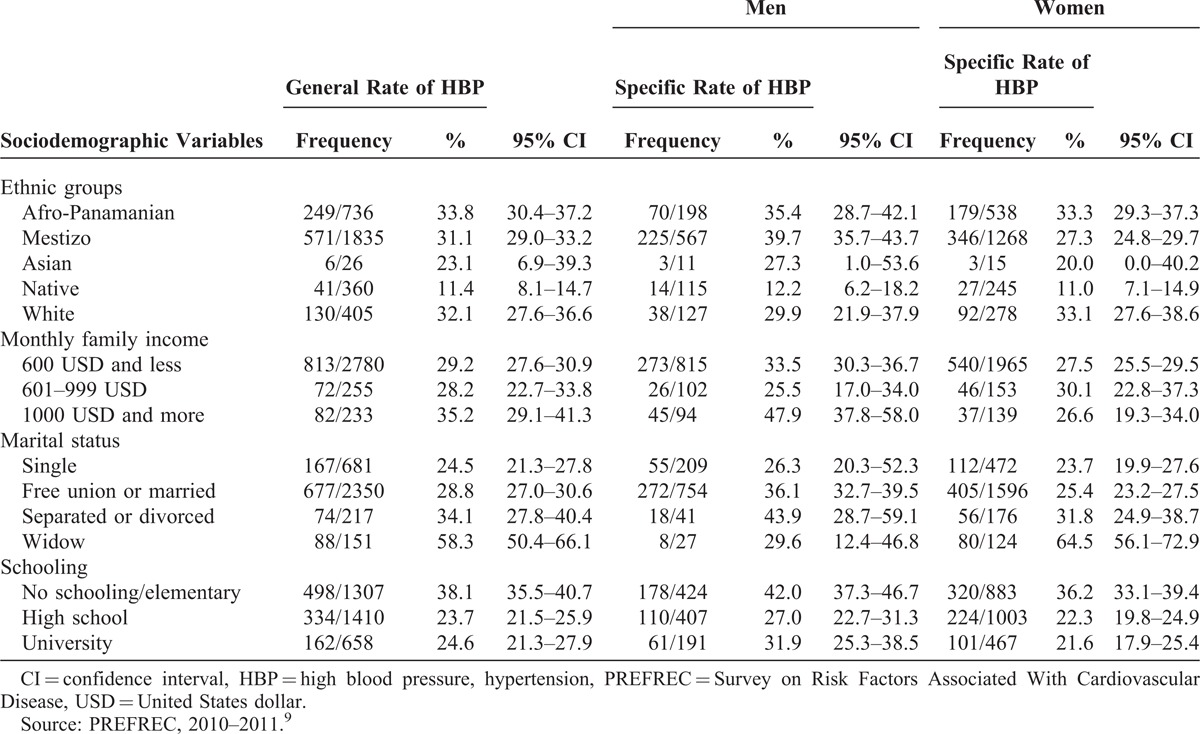

Prevalence of HBP According to Sociodemographic Variables: Ethnocultural Identification, Marital Status, Educational Level, and Income Status

The prevalence of HBP was 33.8% (249/736; 95% CI, 30.4–37.2) among Afro-Panamanians, 32.1% (130/405; 95% CI, 27.6–36.6) among whites, and 31.1% (571/1835; 95% CI, 29.0–33.2) among Mestizos. The lowest prevalence of HBP was found among Amerindians (Gunas) 11.4% (41/360; 95% CI, 8.1–14.7) (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

General and Specific Rates of HBP by Sex According to the Sociodemographic Variables

With regards to income, men who had a monthly family income of 1000 USD had a prevalence of HBP of 47.9% (45/94; 95% CI, 37.8–58.0), whereas women, with a similar family income, had a prevalence of 26.6% (37/139; 95% CI, 19.3–34.0) OR = 1.88; 95% CI, 1.20–2.94; P = 0.005 (see Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 3.

Risk Factors Associated With HBP by Sex in Panama

In so far as marital status, HBP prevalence was highest among widows, 64.5% (80/124; 95% CI, 56.1–72.9), OR = 5.31 (95% CI, 3.58–7.91), P < 0.001 (see Tables 2 and 3).

The prevalence of HBP was higher among those with no schooling or only with an elementary school education, 38.1% (95% CI, 35.5–40.7) when compared with those with a high school or university education, 24.0%, (95% CI, 22.2–25.8). However, men with a university education had a higher prevalence of HBP, 31.9% (61/191; 95% CI, 25.3–38.5) when compared with women with a similar level of education, 21.6%, (101/467; 95% CI, 17.9–25.4) (see Table 2).

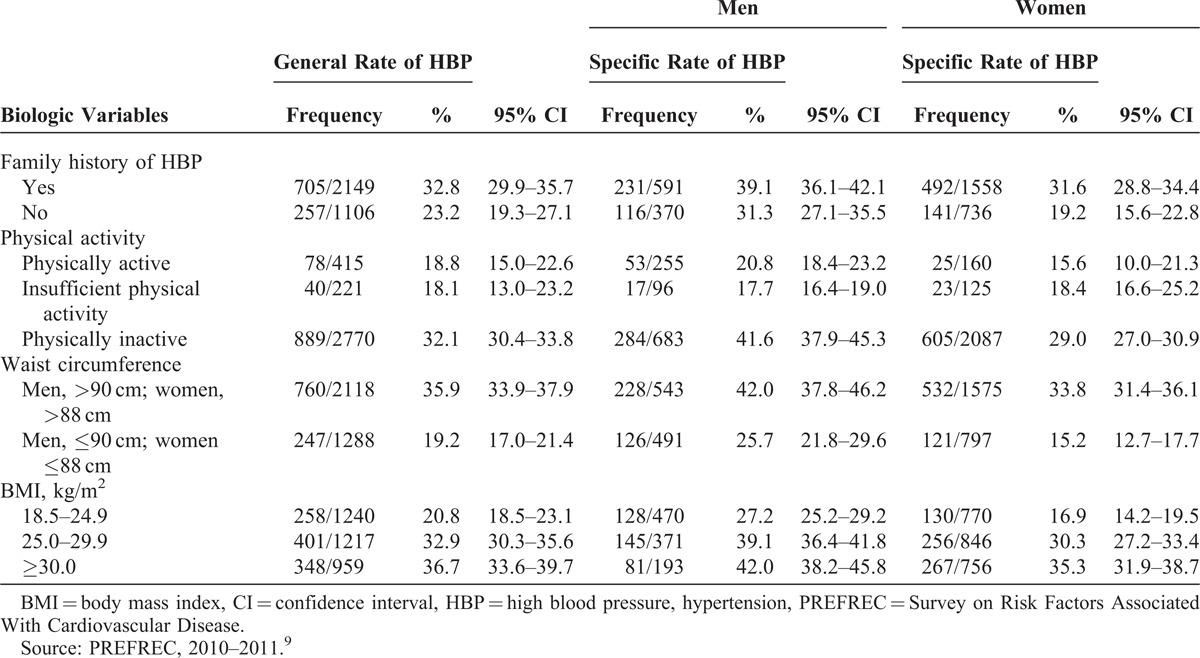

Prevalence of HBP According to Biologic Variables: Family History, Physical Activity, Waist Circumference, and BMI

HBP was more prevalent among those with a family history of HBP, 32.8% (95% CI, 29.9–35.7) than among those without a family history of HBP, 23.2% (95% CI, 19.3–27.1). HBP was also more prevalent among those classified as physically inactive 32.1% (95% CI, 30.4–33.8) than among those classified as physically active 18.8% (95% CI, 15.0–22.6) or even among those classified as engaging in insufficient physical activity. Men with a waist circumference >90 cm and women with a waist circumferences >88 cm had a higher prevalence of HBP than those men and women with smaller waist circumferences. The same was observed for men and women with BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2 (see Table 4).

Table 4.

General and Specific Rates by Sex of HBP According to Biologic Variables

Risk Factors Associated With HBP

For men, HBP was associated mainly with being 50 years old or older (OR = 3.29 [95% CI, 2.51–4.32], P < 0.001), being physically inactive (OR = 2.71 [95% CI, 1.91–3.86], P < 0.001), having a waist circumference of >90 cm (OR = 2.10 [95% CI, 1.60–2.76], P < 0.001), having a family income of USD 1000 or more per month (OR = 1.88 [95% CI, 1.20–2.94], P = 0.005), having a BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2 (OR = 1.79 [95% CI, 1.37–2.33], P < 0.001), having no schooling or only elementary school education (OR = 1.78 [95% CI, 1.36–2.34], P < 0.001), or being Mestizo (OR = 1.72 [95% CI, 1.31–2.26], P < 0.001) (see Table 3).

For women, HBP was associated mainly with being 50 years old or older (OR = 5.96 [95% CI, 4.89–7.25], P < 0.001), having a waist circumference >88 cm (OR = 2.85 [95% CI, 2.27–3.57], P < 0.001), having a BMI ≥25.0 kg/m2 (OR = 2.39 [95% CI, 1.92–2.96], P < 0.001), being physically inactive (OR = 2.20 [95% CI, 1.40–3.50], P < 0.001), having no schooling or only an elementary school education (OR = 1.97 [95% CI, 1.64–2.38], P < 0.001), having a family history of HBP (OR = 1.95 [95% CI, 1.57–2.42], P < 0.001), being Afro-Panamanian (OR = 1.43 [95% CI, 1.16–1.77], P = 0.001), or living in urban areas (OR = 1.31 [95% CI, 1.09–1.57], P = 0.004) (see Table 3).

HBP Awareness, Treatment, and Control

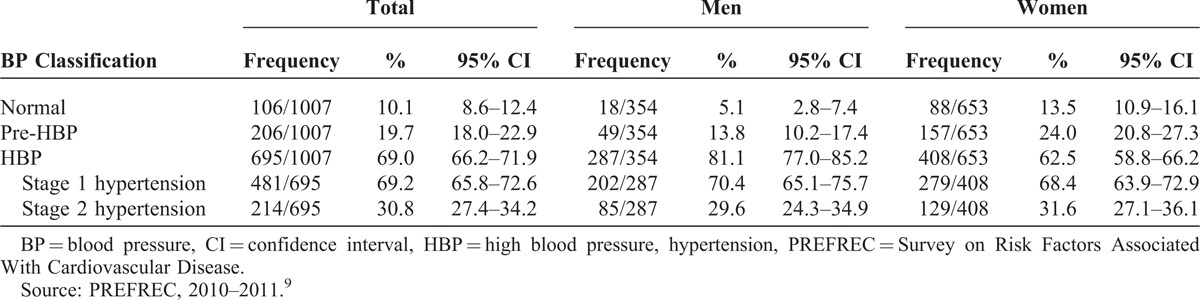

Of the 1007 people documented as having HBP, 65.6% (661/1007; 95% CI, 62.7–68.5) were taking antihypertensive medications, 33.7% (339/1007; 95% CI, 30.8–36.6) were aware of having HBP but were not taking medication, and 34.3% (345/1007 (95% CI, 31.4–37.2) were unaware of having HBP. Of the 661 people who were taking medications for HBP, 47.2% (312/661; 95% CI, 43.4–51.0) had BP values of <140/90 mm Hg and 52.8% (349/661; 95% CI, 49.0–56.6) had BP values ≥140/90 mm Hg (see Table 5).

TABLE 5.

BP Classification Among People With HPB According to Sex

More subjects >60 years of age were aware of having HBP when compared with those 40–59 years old (OR = 1.61 [95% CI, 1.18–2.19], P = 0.002). Nevertheless, the percentage of those with controlled HBP decreased with increasing age as demonstrated by better HBP control among the 18 to 39-year-old group than among those who were 60 years and older, OR = 2.62 (95% CI, 1.37–5.04), P = 0.002 (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

HBP in Panama: awareness, treatment and control according to age and sex. A, unaware (men); B, unaware (women); C, aware and treated (men); D, aware and treated (women); E, controlled (men); F, controlled (women). HBP = high blood pressure, hypertension, PREFREC = Survey on Risk Factors Associated With Cardiovascular Disease. Source: PREFREC, 2010–2011.9

DISCUSSION

PREFREC is the first cardiovascular risk factor study ever to have been conducted in Panama where BP was measured. The results from PREFREC suggest that the prevalence of HBP is 29.6% (95% CI, 28.0–31.1) among subjects 18 years of age or older who live in the highly urbanized provinces of Panama and Colon, an area where approximately 60% of the country’s population resides. Based on this prevalence estimate, HBP is probably the most common cardiovascular risk factor in Panama.9,11,21,22

The results reveal that HBP in Panama is associated with the following factors: age, living in an urban area, having no formal education or only an elementary level education, having a family income >1000 USD/mo if men, being physically inactive, having a larger than normal waist circumference, and having a BMI ≥25 kg/m2. These associations give new insights on the risk factors of HBP in Panama and complement existing information that have been reported for other countries in the Americas.1,2,5,7,21,23–31

The high prevalence of HBP (29.6%), especially the prevalence of 7.1% seen among those aged between 18 and 29 years of age, is of concern because it implies that there may be >400,000 subjects with HBP in the provinces of Panama and Colon who should be receiving care for this condition and because it resembles the prevalence found in economically affluent countries.29,32

In the last 3 decades, the per capita gross domestic product of Panama increased almost 5-fold and the percentage of people living in urban areas grew from 50% to 75%.33,34 This rapid increase in economic growth and urbanization has resulted in significant nutritional and lifestyle changes.35–38 Changes in occupation, transportation, and technology directed at leisure time activities at home have also contributed to increased sedentary behavior and reduced physical activity.39,40 Therefore, the problem of HBP in Panama has to be analyzed and managed in the light of these lifestyle alterations.

As reported by other studies, we found a progressive increase in the prevalence of HBP with aging.1,32,41–43 More than half of the adults of 60 to 69 years were found to be hypertensive as well as 62.2% of those older than 70 years, something comparable to the prevalence reported for North Americans8,27 and Mexicans from Monterrey of the same age group.44 This finding is an alert of the heightened risk for CVD for many older adults in Panama for cerebrovascular disease and dementia.45 It also highlights important and difficult clinical issues in the management of systolic and secondary HBP in the elderly.

The prevalence of HBP was shown to be higher in men than in women,2,29 differing from what has been found in other studies.27,32,42 However, the prevalence of HBP among those 60 years or older was higher in women than in men.3,46,47 The lower prevalence of HBP noted in men >60 years of age may in part be related to the lower prevalence of obesity seen in Panamanian men >60 years when compared with women of the same age group.48 The prevalence of HBP among of those who reside in indigenous areas was almost 3 times lower than among those who live in urban areas. Native Americans (Gunas) had the lowest prevalence of HBP of all the ethnocultural groups evaluated in Panama. The lower prevalence of HBP seen among the Gunas may in part be because of their diet, higher levels of physical activity during their daily activities, and also a lower prevalence of obesity. A low prevalence of HBP was reported by Kean49–51 among the Gunas in 1943 and has also been reported in indigenous groups from Honduras and North America.

When looking at ethnocultural factors, the highest percentage of HBP was found among the people with African descent, a finding that has been previously reported in Panama and in other countries of this continent.27,30,41,52–54 Food preferences influenced by ethnocultural factors, a higher prevalence of obesity, and a lower socioeconomic status common in women of African descent probably predispose them to a high prevalence of HBP.30,41,55,56

Elevated BP was inversely proportional to the level of education attained, being higher among those subjects with no schooling or with an elementary school education than among those with a high school or university education. This inverse relationship has also been reported by other authors.47,57 A higher education level may sensitize people to the health risks associated with HBP to follow healthier lifestyles and better access to health care.

In men, we found an association between a family income >1000 USD/mo and HBP, but this was not the case for women. This difference in the prevalence of HBP in part may be because in Panamanian men there is an association between higher income and abdominal obesity, but this is not the case for women.48 In women with a higher income, a slender figure is socially valued and better weight control is possible because they have the means to choose healthier diets and engage in exercise routines, whereas a larger body size, in general, is not perceived as a social handicap for men.

The increases in sedentary behavior and consumption of diets high in carbohydrates and in salt-rich processed foods, which have taken place in the last decades, have led to increases in obesity, larger waist circumferences, and physical inactivity, which have been strongly associated with HBP by this study. Therefore, public health programs aimed at controlling HBP will have to develop strategies and effective mechanisms to modify the unhealthy behaviors brought about by recent changes in lifestyles.

The prevalence of subjects with HBP who were taking antihypertensive medications was higher than that reported by other countries in this continent, such as Peru in 2006 and Mexico (Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición, 2006)6,23 but lower than that reported by the National Health Survey of the United States (NHANES) 2011–2012.29 In PREFREC, BP was found to be controlled in 47.2% of the those who reported to be taking antihypertensive medications, and these results are also higher than the ones reported by Peru and Mexico in the National Health Survey 2000 and, again, lower than the one reported in NHANES in 2011–2012.6,29,31

Overall, 52.8% of those receiving treatment for HBP had levels ≥140/90 mm Hg, but the prevalence in older adults was even higher. Uncontrolled HBP may be not only because of nonadherence to drug treatment,41 but also because of a host of factors such as not making the needed lifestyle and dietary changes, which are an integral part in the management of HBP, not using the appropriate combination of medicines indicated in the systolic HBP of the elderly, or socioeconomic factors that limit access to health care.18,58 Although the percentage of subjects under treatment with controlled HBP was higher than what has been reported in other countries,2,3,6,32 it is discouraging to find out that almost 1/3 of those found to have HBP in this study were unaware of being hypertensive.

Limitations

Despite the fact that this study was conducted with a methodology aimed at reducing bias, there was a higher participation of women than men. This result may be related to the type of sampling strategy that was used (stratified according to education level) and the usual greater participation of women in population-based research. Although the PREFREC sample included the 2 provinces where >60.4% of the inhabitants of the country reside and also included urban, rural, and indigenous areas, PREFREC is not a national study and could have had differences with results from a nationwide study that has not been done yet. The use of automatic sphygmomanometers could have caused underestimation or overestimation of BP levels. However, proper training of the interviewers in the handling, care, and calibration of equipment, use of an appropriate cuff size, coupled with BP measurement on 3 occasions, and the use of average BP for statistical analysis decreased the risk of measurement error. Another limitation in the scope of the study was that we did not include in this analysis the association HBP with diet, salt intake, or alcohol consumption.

Because of budget limitations, the study could not be conducted across the country.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study provide the first estimate of the prevalence of HBP in Panama and its association with socioeconomic and biologic variables. From these estimates, we can conclude that HBP is the most common cardiovascular risk factor among Panamanians and that the health care system needs to give a high priority to HBP prevention programs and integrated care programs aimed at treating HBP. A greater effort is needed to diagnose the large number of hypertensives who are unaware of their condition. Similarly, new strategies need to be introduced in the clinical management of older adults to reduce the incidence of preventable CVD. However, most importantly, all initiatives directed at the prevention and control of HBP in Panama will have to take into consideration the changes in behavior that have brought about changes in nutrition and sedentary lifestyles that are at the heart of this serious public health problem.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the researchers and the technical and administrative personnel who participated in developing PREFREC 2010–2011.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index, BP = blood pressure, CI = confidence interval, CVD = cardiovascular disease, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, GMI = Gorgas Memorial Institute of Health Research, HBP = high blood pressure, hypertension, INEC = Panama’s National Institute of Statistics and Census, MOH = Panamanian Ministry of Health, NHANES = National Health Survey of the United States, OR = odds ratio, PREFREC (for its acronym in Spanish) = PREFREC (for its acronym in Spanish)Survey on Risk Factors Associated With Cardiovascular Disease, SBP = systolic blood pressure, WHO = World Health Organization.

This study was funded by Gorgas Memorial Institute of Health Research.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Armas de Hernandez MJ, Armas Padilla MC, Hernández Hernández R. Hypertension in Latin America. Latin Am J Hypertens. 2006;1:10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunstmann FS. Epidemiology of Hypertension in Chile. Rev Med Clin Condes. 2005;16:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abondano A, Alvarado A, Angulo V, et al. Prevalence of Hypertension in the Sanitation Districts of Carabobo, Venezuela. Medical Report. 2007;9:501–507. [Google Scholar]

- 4.INEC. Vital Statistics: Deaths in the Republic by month of occurrence, according to cause and medical certification Panama General Contraloria of the Republic. Panama: National Institute of Statistics and Census; 2012. http://www.contraloria.gob.pa/dec/inec/archivos/P5201Cuadro%20221-14.pdf Accessed April 19, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Prevalence, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension—United States, 1999–2002. USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5401a3.htm Accessed March 25, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agusti CR. Epidemiology of hypertension in Peru. Acta Med Per. 2006;23:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Copani JM. Prevalence of Hypertension and Associated Risk Factors. http://www.smiba.org.ar/med_interna/vol_04/04_06.htm Accessed September 25, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostchega Y, Dillon C, Hugues J, et al. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in older U.S. adults: data from the national health and nutrition examination survey 1988 to 2004. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1056–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mc Donald Posso AJ, Motta Borrel JA, Roa R, et al. Prevalence of Risk Factors Associated With Cardiovascular Disease (PREFREC) 2010 Panama. Panama: Gorgas Memorial Institute of Health Studies; 2012. http://www.gorgas.gob.pa/prefrec/ Accessed October 23, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.INEC. Vital Statistics: Estimates and Projections of the Total Population, Province and Indigenous Comarca by Sex and Age: 1 July 2000 to 2030 Panama: General Contraloria of the Republic. National Institute of Statistics and Census; 2000. http://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/Publicaciones/Publicaciones.aspx?ID_SUBCATEGORIA=10&ID_PUBLICACION=491&ID_IDIOMA=1&ID_CATEGORIA=3 Accessed March 20, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mc Donald Posso AJ, Montenegro Gonález JA, Cruz González CE, et al. Prevalence, sociodemographic distribution, treatment and control of diabetes mellitus in Panama. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashwell M, Gunn P, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2012;13:275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara A, Meaney A, Kuri Morales P, et al. Frecuencia de obesidad abdominal en médicos mexicanos de primer contacto y en sus pacientes. Med Int Mex. 2007;23:391–397. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nazare J-A, Smith JD, Borel A-L, et al. Ethnic influences on the relations between abdominal subcutaneous and visceral adiposity, liver fat, and cardiometabolic risk profile: the International Study of Prediction of Intra-Abdominal Adiposity and Its Relationship With Cardiometabolic Risk/Intra-Abdominal Adiposity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:714–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan American Hypertension Initiative. Workshop on measurement of blood pressure: recommendations for population studies. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2003;14:303–305. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertomeu Martínez V. Guidelines about the treatment of hypertension 2003: clarify or confuse? Rev Esp Cardiol. 2003;56:940–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark ML. The P values and confidence intervals: in what to trust? Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2004;15:293–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newcombe RG, Merino Soto C. Confidence intervals for estimates of proportions and the differences between them. Interdisciplinaria. 2006;23:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno de Rivera A, Roa R, Mc Donald A, et al. National Survey of Health and Quality of Life, 2007 Panama. Panama: Gorgas Memorial Institute of Health Studies; 2009. http://www.gorgas.gob.pa/enscavi/ Accessed March 24, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jan C, Lee M, Roa R, et al. The Association of Tobacco Control policies and the risk of acute myocardial infarction using hospital admissions data. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e88784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barquera S, Campos-Nonato I, Hernández-Barrera L, et al. Hypertension in Mexican adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Survey 2006. Salud Pública de México. 2010;52suppl 1:S63–S71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casteñanos Arias JA, Negrín La Rosa R, Cubero Menéndez O. Prevalence of hypertension in a community in the municipality of Cardenas. Rev Cubana Med Integr. 2000;16:138–143. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper R, Rotimi C, Ataman S, et al. The prevalence of hypertension in seven populations of west African origin. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curto S, Prats O, Ayestarán R. Investigación sobre factores de riesgo cardiovascular en Uruguay. Rev Med Uruguay. 2004;20:61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Neal Axon R. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nigro D, Vergottini JC, Kuschnir E, et al. Epidemiology of hypertension in the city of Córdoba, Argentina. Rev Fed Arg Cardiol. 1999;28:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nwankwo T, Yoon SSS, Burt V, et al. Hypertension Among Adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013:1–8. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db133.pdf Accessed April 20, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olives C, Myerson R, Mokdad AH, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in United States counties, 2001–2009. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Velázquez Monroy Ó, Rosas Peralta M, Lara Esqueda A, et al. ; ENSA Group-2000. Hypertension in Mexico: Results from the National Health Survey (ENSA) 2000. Archives of Cardiology, Mexico. 2002;72:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindblad U, Ek J, Eckner J, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension: rule of thirds in the Skaraborg project. Journal of Primary Health Care. 2012;30:88–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.GDP per capita. The World Bank website. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD Accessed May 7, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Urban Population. The World Bank website. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS Accessed May 7, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ford ES, Mokdad AH. Epidemiology of obesity in the western hemisphere. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(11 suppl 1):S1–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neuman M, Kawachi I, Gortmaker S, et al. Urban–rural differences in BMI in low- and middle-income countries: the role of socioeconomic status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:428–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Popkin BM, Doak CM. The obesity epidemic is a worldwide phenomenon. Nutr Rev. 1998;56:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webber L, Kilpi F, Marsh T, et al. High rates of obesity and non-communicable diseases predicted across Latin America. PLoS ONE. 2013;7:e39589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cuevas A, Alvarez V, Olivos C. The emerging obesity problem in Latin America. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2009;7:281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ebrahim S, Kinra S, Bowen L, et al. The effect of rural-to-urban migration on obesity and diabetes in India: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hypertension in America: a national reading. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11suppl 13:S383–S385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vasan RS, Levy D. Rates of progression to hypertension among non-hypertensive subjects: implications for blood pressure screening [Letter]. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1067–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang TJ, Vasan RS. Epidemiology of uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. Circulation. 2005;112:1651–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cárdenas Ibarra L, Villarreal Pérez JZ, Rocha Romero F, et al. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes and hypertension in adults of low economic level of Monterrey, Mexico. Universitaria Medicine. 2007;9:64–67. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharp SI, Aarsland D, Day S, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Society Vascular Dementia Systematic Review Group. Hypertension is a potential risk factor for vascular dementia: systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant DC, Fasce HE, Fasce VF. Hypertension and menopause. Rev Med Clin Condes. 2009;20:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pereira M, Lunet N, Paulo C, et al. Incidence of hypertension in a prospective cohort study of adults from Porto, Portugal. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2012;12:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sasson M, Lee M, Jan C, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of obesity among Panamanian adults. 1982–2010. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foulds HJ, Warburton DE. The blood pressure and hypertension experience among North American indigenous populations. J Hypertens. 2014;32:724–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kean BH. The blood pressure of the Cuna Indians. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1944;24:341–343. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reyes-García SZ, Zambrano LI, Fuentes I, et al. Descriptive study of cardiovascular risk factors in a sample of the population of an indigenous community in Honduras. CIMEL. 2011;14:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carson AP, Howard G, Burke G, et al. Ethnic differences in hypertension incidence among middle-aged and older adults: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2011;57:1101–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kean BH. Blood pressure studies on West Indians and Panamanians living on the Isthmus of Panama. Arch Intern Med (Chic). 1941;68:466–475. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holmes L, Hossain J, Ward D, et al. Racial/ethnic variability in hypertension prevalence and risk factors in national health interview survey. ISRN Hypertension. 2013;2013Article ID 257842. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones DW, Hall JE. Racial and ethnic differences in blood pressure: biology and sociology [Letter]. Circulation. 2006;114:2757–2759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navarro Lechuga E, Vargas Moranth R. Diferencias de hipertensión por género en pacientes negros. Salud Uninorte. 2009;24:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Selem S, Castro M, César C, et al. Validity of self-reported hypertension is inversely associated with the level of education in Brazilian individuals. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2012;100:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coca A. Hypertension and vascular dementia in the elderly: the potential role of anti-hypertensive agents. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:1045–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]