Abstract

Urticarial vasculitis (UV) is a subset of cutaneous vasculitis (CV), characterized clinically by urticarial skin lesions of more than 24 hours’ duration and histologically by leukocytoclastic vasculitis. We assessed the frequency, clinical features, treatment, and outcome of a series of patients with UV. We conducted a retrospective study of patients with UV included in a large series of unselected patients with CV from a university hospital. Of 766 patients with CV, UV was diagnosed in 21 (2.7%; 9 male and 12 female patients; median age, 35 yr; range, 1–78 yr; interquartile range, 5–54 yr). Eight of the 21 cases were aged younger than 20 years old. Potential precipitating factors were upper respiratory tract infections and drugs (penicillin) (n = 4; in all cases in patients aged <20 yr), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (n = 1), and malignancy (n = 1). Besides urticarial lesions, other features such as palpable purpura (n = 7), arthralgia and/or arthritis (n = 13), abdominal pain (n = 2), nephropathy (n = 2), and peripheral neuropathy (n = 1) were observed. Hypocomplementemia (low C4) with low C1q was disclosed in 2 patients. Other abnormal laboratory findings were leukocytosis (n = 7), increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (n = 6), anemia (n = 4), and antinuclear antibody positivity (n = 2). Treatment included corticosteroids (n = 12), antihistaminic drugs (n = 6), chloroquine (n = 4), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (n = 3), colchicine (n = 2), and azathioprine (n = 1). After a median follow-up of 10 months (interquartile range, 2–38 mo) recurrences were observed in 4 patients. Apart from 1 patient who died because of an underlying malignancy, the outcome was good with full recovery in the remaining patients. In conclusion, our results indicate that UV is rare but not exceptional. In children UV is often preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection. Urticarial lesions and joint manifestations are the most frequent clinical manifestation. Low complement serum levels are observed in a minority of cases. The prognosis is generally good, but depends on the underlying disease.

INTRODUCTION

The vasculitides are a heterogeneous group of conditions characterized by blood vessel inflammation and necrosis.16 Urticarial vasculitis (UV) is a subset of cutaneous vasculitis (CV) described by McDuffie et al34 in 1973 and characterized clinically by urticarial skin lesions lasting longer than 24 hours and histologically by vasculitis. Urticarial skin lesions in this condition consist of an eruption of erythematous wheals that clinically resemble urticaria but histologically show changes of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.38,50 UV may be divided into normocomplementemic and hypocomplementemic variants. Both subsets can be associated with systemic symptoms such as angioedema, arthralgia or arthritis, abdominal or chest pain, fever, pulmonary disease, renal disease, episcleritis, uveitis, and Raynaud phenomenon. The hypocomplementemic form is more often associated with systemic symptoms and has been associated with connective tissue disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).43,49

The incidence of UV remains unclear. Because of that, we assessed the frequency, clinical features, treatment, and outcome of all patients diagnosed as having UV from a large series of unselected patients with CV.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

We reviewed the case records of patients from a teaching reference hospital in Northern Spain (Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander) in whom CV was diagnosed from January 1976 to December 2011. Methods were similar to those previously reported.4 Briefly, the diagnosis of CV was based on either 1) a skin biopsy showing characteristic pathologic findings of vasculitis, 2) the presence of typical nonthrombocytopenic palpable purpura, or 3) a clinically evident syndrome in the pediatric age.

UV was considered to be present when the patient had urticarial lesions (Figures 1A and 1B) lasting more than 24 hours and a skin biopsy showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figures 2A and 2B). An exception to that was considered in 2 patients aged 1 year presenting with typical urticarial lesions lasting more than 24 hours in whom the pediatricians did not perform a skin biopsy.

FIGURE 1.

Typical urticarial lesions in a patient presenting with urticarial vasculitis (A and B; residual purpuric lesions can be observed in B).

FIGURE 2.

A, Perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of polymorphonuclear neutrophils and eosinophils ( white arrow) with leukocytoclastic venulitis. (Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification × 100.) B, Perivascular eosinophilic infiltrate with fibrin deposits (short white arrow) and karyorrhexis (long white arrow). (Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification × 200.)

Clinical and Laboratory Definitions

We used the following definitions: 1) Patients aged older than 20 years were considered adults. The cutoff of 20 years was chosen because this age was proposed as a criterion by the American College of Rheumatology.36,37 2) Fever was defined as an axillary temperature >37.7°C. 3) Constitutional syndrome: asthenia and/or anorexia, and weight loss of at least 4 kg. 4) Joint symptoms included arthralgia and/or joint effusion. 5) Gastrointestinal manifestations: bowel angina (diffuse abdominal pain worsening after meals), gastrointestinal bleeding (melena, hematochezia, or positive stool Guaiac test), nausea and/or vomiting. 6) The nephropathy was categorized as mild or severe. Mild nephropathy included those patients with microhematuria (≥5 red cells/high power field) without reaching nephritic syndrome and/or proteinuria that did not reach the nephrotic range. 7) A relapse was considered to be present when a patient previously diagnosed as having CV and asymptomatic for at least 1 month presented again a new flare of cutaneous lesions. Anemia was defined as a hemoglobin level ≤110 g/L. Leukocytosis was defined if a white cell count was ≥11 × 109/L, and leukopenia was defined as a leukocyte count <3 × 109/L. The Westergren erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) in mm/h was considered elevated when it was higher than 15 or 20 mm/h for male or female patients, respectively.

Clinical Study

ln most patients presenting with CV, routine laboratory studies, including complete blood cell count, coagulation studies, and liver and renal function tests, were performed at the time of diagnosis. In addition, ESR, routine urinalysis, and chest radiographs were performed.

An immunologic profile was carried out in most adults (but only in a minority of children). It included rheumatoid factor (RF), performed until the late 1980s by quantitative latex agglutination test, and later by nephelometry; antinuclear antibodies (ANA), by indirect immunofluorescence using rodent tissues as substrate until the late 1980s and since then by Hep-2 cells; serum levels of C3 and C4, first by radial immunodiffusion and more recently by nephelometry; and cryoglobulins. The composition of the cryoprecipitate was determined by double immunodiffusion with specific antibodies. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) were assessed initially by indirect immunofluorescence on alcohol-fixed neutrophils, and later, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with purified proteinase-3 and myeloperoxidase. ANCAs were only assessed in patients seen since 1990. Other tests, such as anti-nDNA antibodies (by immunofluorescence with Crithidia luciliae as substrate), blood cultures, Guaiac test for occult blood, bone marrow biopsy, and serology for hepatitis B, C, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, were performed only when they were clinically indicated.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Data were first reviewed and then analyzed to study etiologic, clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic features, as well as treatment and prognosis. Data were extracted from patients’ clinical records according to a specifically designed protocol, reviewed for confirmation of the diagnosis, and stored in a computerized file. To minimize entry error all the data were double checked. A comparative study between UV and the remaining CV was performed.

The statistical analysis was performed with the STATISTICA software package (Statsoft Inc. Tulsa, OK). Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for variables with a normal distribution, or as median, range, or interquartile range (25th, 75th) (IQR) for those not normally distributed. Continuous variables (normally and not normally distributed) were compared with the 2-tailed Student t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. The chi-square test or the Fisher exact test was used for dichotomous variables. Statistical significance was considered as a p value < 0.05.

The current study was a retrospective review of cases diagnosed with UV. No specific request for the review was made to our local ethical committee for that purpose. However, ethical committee approval (Ethical Committee of Cantabria, Spain) was obtained to perform studies on genetic markers of patients with CV that are underway.

RESULTS

We assessed the medical records of a series of 766 patients (346 female/420 male patients) from a university hospital in Santander, Spain, in whom CV was diagnosed between January 1976 and December 2011. The mean age of the entire series was 34.0 ± 27.5 years (range, 1–95 yr). Of the 766 patients, 421 (178 female/243 male patients) were aged more than 20 years, with a mean age of 55.6 ± 17.5 years (range, 24–95 yr).

Frequency and Demographic Data of Patients With UV

UV was diagnosed in 21 of 766 patients with CV: 9 male and 12 female patients; median age, 35 yr (range, 1–78 yr; IQR, 5–54 yr). These patients constituted 2.7% of the whole series of 766 of CV patients. Thirteen of them were aged more than 20 years (5 men and 8 women; median age, 44 yr; range, 28–78 yr; IQR, 37–67 yr). They constituted 3.1% of the series of 421 adults with CV.

Main Clinical Features

Skin lesions were the first clinical manifestation in the 21 patients with UV. The most frequent skin lesions were wheals lasting more than 24 hours that were painful and burning (Table 1). In most cases cutaneous lesions were located in the extremities and trunk and had a mean duration of 10.71 ± 9.35 days. Other clinical manifestations were arthralgia and/or arthritis (in 13 cases). Two patients had abdominal pain and another 2 patients had nephropathy (in both cases microhematuria). Fever was present in 2 patients, and mononeuritis multiplex in 1 patient. One patient had paraneoplastic CV (megakaryocytic leukemia).31

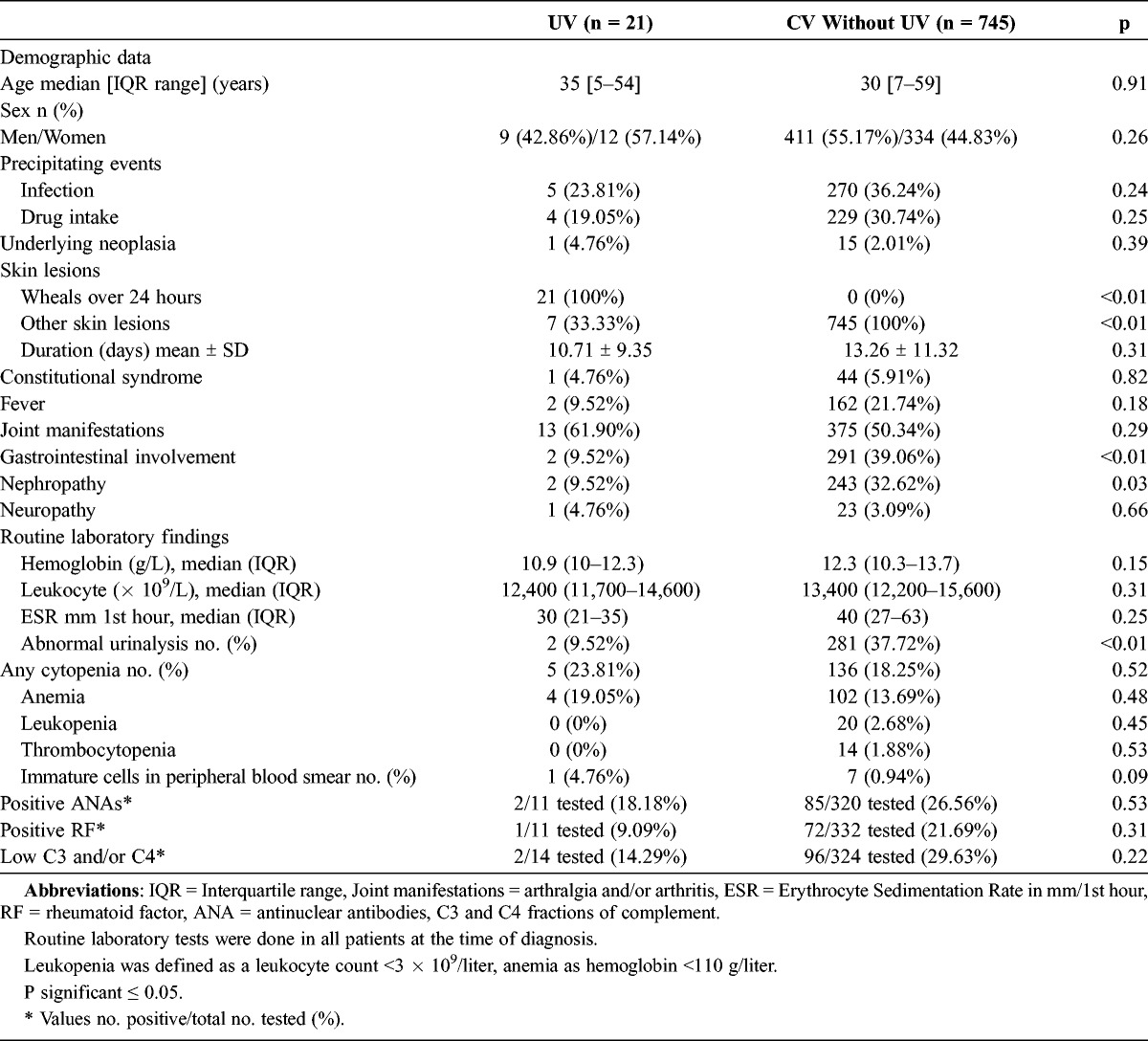

TABLE 1.

Main Features of 21 Patients With Urticarial Vasculitis From a Single Center

Four of the 8 children (defined as patients aged ≤20 yr) had an upper respiratory tract infection within the week before the onset of UV. All of them had been treated with penicillin before admission. In the group of adults (aged >20 yr), potential association with infection was disclosed in only 1 patient, who was diagnosed with HIV infection during admission for UV.

None of pediatric patients fulfilled previously established definitions for Henoch-Schönlein purpura at the time of diagnosis or during follow-up. Overall, in patients aged ≤20 years, the clinical features were usually milder than in adults.

Laboratory and Pathologic Findings

The registered immunologic parameters of our patients were C3, C4, C1q, RF, ANA, and ANCAs. Children less commonly had laboratory abnormalities. As shown in Table 1, hypocomplementemia (low C4) was observed in 2 of 21 patients with UV. In both cases it was associated with low C1q. Other abnormal laboratory data observed were leukocytosis (7 cases), increased ESR (6 cases), anemia (4 cases), positive ANA (2 cases), and positive RF (1 case). None of the patients with positive ANA or RF developed SLE, rheumatoid arthritis, or any other connective tissue disease during follow-up.

Skin punch biopsy was performed in 19 patients. As previously mentioned, it was not performed in 2 patients aged 1 year. In these 2 pediatric cases the clinical features were compatible with UV. Characteristic histologic findings, such as neutrophilic infiltration; leukocytoclasia; and fibrinoid necrosis into the vessel wall of arterioles, capillaries, and postcapillary venules, were observed in the 19 patients in whom a skin biopsy was performed.

Treatment and Outcome

The most common drugs used in the management of UV were corticosteroids (12 cases), antihistaminic drugs (6 cases), chloroquine (4 cases), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (3 cases), and colchicine (2 cases) (see Table 1). An immunosuppressive drug (azathioprine) was required in 1 patient. After a median follow-up of 10 months (IQR, 2–38 mo) recurrences were observed in 4 (19%) of 21 patients. One patient died because of an underlying malignancy, while the remaining patients had full recovery without complications. Relapses were less frequent in the younger age group.

Differences Between Patients With UV and the Remaining Patients With CV

We performed a comparative analysis of differences between patients with UV and the remaining patients with CV (Table 2). A history of previous infection or drug intake before the onset of the vasculitis was less common in the group of patients with UV than in the remaining patients with CV, but the difference was not statistically significant. In addition, gastrointestinal involvement and nephropathy were less frequent in patients with UV.

TABLE 2.

Differences Between Patients With Urticarial Vasculitis (UV) and the Remaining Patients With Cutaneous Vasculitis (CV)

DISCUSSION

The term UV encompasses a syndrome characterized histologically by a small vessel vasculitis in which urticarial skin lesions have a duration of more than 24 hours, unlike what it is observed in cases of urticaria.8,12,28,41,48 UV may be associated with hypocomplementemia and the presence of IgG anti-C1q. Since UV has specific clinical and serologic characteristics, it has been proposed as a separate entity different from the rest of CV. However, the actual proportion of cases with UV in the series of patients with CV remains unknown. In the current series the frequency of UV was 2.7% of the whole series of CV including pediatric patients, and 3.1% when we specifically assessed the frequency in adults with CV. Therefore, our results indicate that UV is rare but not exceptional.

The etiology of UV remains unclear. The pathogenesis of UV is thought to be immune mediated.23 This is a type III hypersensitivity reaction in which antigen-antibody complexes are deposited in the vascular lumen. Many different antigens, both endogenous and exogenous, have been implicated in the formation of antibodies leading to the generation of immune complexes that are deposited in the blood vessels of patients with UV.

Complement is activated by the classical pathway, generating C3a and C5a. These anaphylatoxins stimulate the release of mast cells, promoting neutrophil chemotaxis and increased permeability of vessels.18,24,53 When neutrophils arrive at the site of inflammation, they acquire a phagocytic function and release proteolytic enzymes which further aggravate tissue destruction and edema.3

The C1q molecule has a collagen-like region that forms an antibody-binding site. IgG binds to the Fc fragment of C1q molecules, thereby activating the classical pathway of complement. The activation of this pathway induces mast cell degranulation and the synthesis of cytokines and chemokines, leading to increased vascular permeability, chemotaxis of neutrophils, and increased immune complex deposits.18,24,53 C1q autoantibodies may also play a role in the pathogenesis of the pulmonary disease seen in some cases of UV.10,24,33 A cross-reactivity between antibodies to C1q and pulmonary surfactant apoproteins that contain collagen-like regions similar to C1q has been proposed.2,5 Some lymphoproliferative disorders have been associated with anti-C1q antibodies. Paraproteins may activate C1q circulating through the classic complement pathway thus leading to the depletion of C1q esterase inhibitors.10,24,33

Electronic microscopy indicates that activated platelet aggregates may also play an important role in the pathogenesis of UV.10,39 Destruction of vessels along with the presence of an endothelial inflammatory infiltrate composed of neutrophils and mononuclear cells was observed 32 hours after the intradermal injection of platelet-activating factor.10

UV may occur at any age, but it is more common in the fifth decade. Women are affected twice as often as men.11 It may present with a wide clinical spectrum, ranging from skin lesions exclusively to a severe systemic disease. Clinically, the lesions of UV last longer (generally 3–7 d) than those of ordinary urticaria. The hives present with burning and pain and may leave residual bruising or hyperpigmentation of the skin.54 Some patients may have an associated angioedema in the face or hands. The most common noncutaneous manifestation is arthralgia, but kidney and pulmonary disease and gastrointestinal symptoms have also been reported.3,19 In the current series of UV, arthralgia and arthritis were the most common noncutaneous manifestations.

In most cases, UV is an isolated condition. However, it may present as an entity associated with different conditions, including connective tissue diseases such as SLE or Sjögren syndrome; systemic necrotizing vasculitis; or infections, such as hepatitis B or C, infectious mononucleosis, Coxsackie, and Lyme disease. UV has been described in association with solid or hematologic malignancies.7,15,20,29,31,46,47,51 We reported31 a 40-year-old woman in whom megakaryocytic leukemia was diagnosed. UV has also been described in a few patients after exercise.25 In this regard, Di Stefano et al13 reported a 42-year-old man who presented with a 1-month history of recurring erythematous wheals over the lower extremities that occurred a few hours after physical exercise. Each lesion persisted for more than 24 hours but disappeared in less than 3 days, leaving the area involved with slight pigmentation. Skin biopsy of an urticarial lesion disclosed leukocytoclastic vasculitis, which is the main histologic criterion for differentiating UV from urticaria. Incidentally, a teratoma was diagnosed in the patient. It is noteworthy that once the tumor was surgically removed, the patient had no more UV flares.13

Most reports on UV are limited to the description of a single case, emphasizing that UV may be an uncommon type of vasculitis. Nevertheless, Kulthanan et al27 reported a series of 64 cases in individuals aged more than 18 years. More than 90% of them had erythematous wheals lasting more than 24 hours. Most cases were idiopathic (45 [70%] of 64 patients). Nonetheless, 19 (30%) patients had UV associated with different conditions: 8 cases had UV in the context of an infection (upper respiratory tract infection in 6 patients, and HIV and syphilis in 1 patient each); 5 patients had UV in association with drugs (NSAIDs in 3 patients, and antibiotic and interferon in 1 patient each); 5 patients had UV as a paraneoplastic vasculitis (breast, ovary, thyroid, colon, and pituitary tumors, respectively); and 1 patient had UV in the setting of SLE. In our current series, 100% of patients had urticarial lesions of over 24 hours’ duration. Seven patients had palpable purpura, and 1 of them developed ulcers in the lower limbs.

Several uncommon associations of UV with different conditions have been reported. Ferreira et al14 reported a 38-year-old woman presenting with erythematous, violaceous plaques with a serpinginous and unusual appearance located on the left shoulder, left thigh, and right buttock, evolving in 5 days, which eventually became generalized, and the patient developed thyroiditis. In 2010, Hughes et al21 reported the case of a patient with UV following H1N1 vaccination. In some cases UV has been reported to occur in the setting of an IgM monoclonal gammopathy constituting what is called Schnitzler syndrome. This syndrome, first described in 1972,30,44 is characterized by UV, IgM gammopathy, fever, bone pain, and arthralgia and/or arthritis. In addition, UV has been described in patients with inflammatory bowel disease or Guillain-Barré syndrome, and following exposure to sun and cold. One noteworthy case was reported by Macêdo et al32 of a 12-year-old boy with SLE and dermatomyositis associated with UV syndrome. To our knowledge, this was the first case of triple association (2 connective tissue diseases plus UV) described in the literature.

According to the complement results, UV can be divided into normocomplemetemic or hypocomplementemic.9 Patients with hypocomplementemic UV syndrome are more likely to have an associated connective tissue disease and systemic symptoms than are patients with UV and normal complement levels,43 and they may also have IgG antibodies to the collagen-like domain of C1q.52 Hypocomplementemic UV, like SLE, has been associated with the presence of anti-cell-endothelial antibodies. In our current series only 2 (9.5%) of the 21 patients had low levels of complement. This result is in accordance with the results of Kulthanan et al,27 who described 9.7% of patients with hypocomplementemic UV. However, the results contrast with other studies that described higher frequencies of hypocomplementemia ranging from 20.6% to 64%.6,28,35,45

In the laboratory tests RF may be positive and in hypocomplementemic UV there is a decrease of CH50, C3, and/or C4. When ANA are positive a diagnosis of SLE should be ruled out.

A differential diagnosis with several conditions resembling UV is required when this vasculitis is suspected. Unlike UV, ordinary urticaria (hives) presents with spontaneous wheals anywhere on the body lasting less than 24 hours. The lesions are itchy but not painful or burning, and the biopsy shows a mixed perivascular infiltrate without vasculitis. A condition that may mimic UV is neutrophilic urticaria, which is a variant of urticaria responsive to antihistaminic drugs characterized by chronic urticaria and neutrophil infiltration without vasculitis. Another condition to be excluded is urticarial arthritis, which is characterized by bouts of arthritis, urticaria (lasting <24 h), and facial angioedema in HLA-B51-positive patients.40 Some patients with urticarial arthritis may have a biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis, while others may have only an infiltrate without damage in the vessel wall. Finally, as discussed above, in cases of UV we have to rule out the presence of an underlying connective tissue disease, mainly SLE, and a malignancy. Other conditions that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a patient presenting with UV are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Main Entities That Should be Considered in the Differential Diagnosis of Urticarial Vasculitis

Treatment of UV differs from treatment of ordinary chronic urticaria, and depends on whether there is systemic involvement and/or an underlying disease. Corticosteroids are generally the most effective drugs, but some patients with UV may require high doses, with relapses relatively common when the corticosteroid dose is tapered. Antihistaminic drugs and NSAIDs can be used in cases of UV limited to the skin. In cases refractory to these medications other drugs such as colchicine, dapsone, azathioprine, or hydroxychloroquine may be used. Cases reporting improvement of joint symptoms following intramuscular gold therapy have been described.46 There are also case reports of patients with refractory UV responding to rituximab43 and mycophenolate mofetil.55 In the series by Kulthanan et al,27 the drugs used included oral antihistamines (68.8%), colchicine (65.6%), NSAIDs (42.4%), and systemic corticosteroids (40.6%). In our current series the most common drugs prescribed were corticosteroids and antihistaminic drugs, and only a single patient required immunosuppressive therapy.

Plasmapheresis has proved beneficial in the treatment of some patients with CV and UV1,17,22,42 because it allows the removal of the circulating immune complexes. Kartal et al26 reported the case of a 35-year-old woman with a 9-year history of recurrent episodes of UV refractory to different therapies who achieved clinical improvement following plasmapheresis.

In cases associated with a specific disease, the prognosis depends on the underlying disease. In idiopathic cases UV is usually benign, but it can follow a chronic course lasting up to 3 years.

In conclusion, our results indicate that UV is rare but not exceptional. In children, UV is often preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection. Urticarial lesions and joint manifestations are the most frequent clinical manifestations. Low complement serum levels are observed in a minority of cases. The prognosis is generally good but depends on the underlying disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the members of the Rheumatology, Dermatology, Pediatrics, and Pathology Services of Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander, Spain.

Abbreviations

- ANA

antinuclear antibodies

- ANCAs

antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

- CV

cutaneous vasculitis

- ESR

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- IQR

interquartile range

- NSAIDs

nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs

- RF

rheumatoid factor

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- UV

urticarial vasculitis

Footnotes

*Drs. González-Gay and Blanco share senior authorship.

Financial support and conflicts of interest: This study was supported by grants from “Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias” PI12/00193 (Spain). This work was also partially supported by RETICS Programs, RD08/0075 (RIER) and RD12/0009/0013 from “Instituto de Salud Carlos III” (ISCIII) (Spain). The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander JL, Kalaaji AN, Shehan JM, Yokel BK, Pittelkow MR. Plasmapheresis for refractory urticarial vasculitis in a patient with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:534–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babajanians A, Chung-Park M, Wisnieski JJ. Recurrent pericarditis and cardiac tamponade in a patient with hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg RE, Kantor GR, Bergfeld WF. Urticarial vasculitis. Int J Dermatol. 1988;27:468–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco R, Martinez-Taboada VM, Rodriguez-Valverde V, Garcia-Fuentes M. Cutaneous vasculitis in children and adults. Associated diseases and etiologic factors in 303 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1998;77:403–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewer JD, Davis MDP. Urticarial vasculitis. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate website. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callen JP, Kalbfleisch S. Urticarial vasculitis: a report of nine cases and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1982;107:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvo-Romero JM. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma in a patient with hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis. J Postgrad Med. 2003;49:252–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang S, Carr W. Urticarial vasculitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28:97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis MD, Daoud MS, Kirby B, Gibson LE, Rogers RS., III Clinicopathologic correlation of hypocomplementemic and normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:899–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis MD, Brewer JC. Urticarial vasculitis and hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome [review]. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:183–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deacock SJ. An approach to the patient with urticaria. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153:151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dincy CV, George R, Jacob M, Mathai E, Pulimood S, Eapen EP. Clinicopathologic profile of normocomplementemic and hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: a study from South India. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:789–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Stefano F, Siriruttanapruk S, Di Gioacchino M. Exercise-induced urticarial vasculitis as a paraneoplastic manifestation of cystic teratoma. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1418–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferreira O, Mota A, Baudrier T, Azevedo F. Urticarial vasculitis reveals unsuspected thyroiditis. Acta Dermatoveneorologica. 2012;21:37–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Porrua C, Gonzalez-Gay M. Cutaneous vasculitis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in adults. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1133–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2001;27:729–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grattan CE, Francis DM, Slater NG, Barlow RJ, Greaves MW. Plasmapheresis for severe, unremitting, chronic urticaria. Lancet. 1992;339:1078–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grotz W, Baba HA, Becker JU, Baumgartel MW. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome: an interdisciplinary challenge. Dtsch Arzteblatt Int. 2009;106:756–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Handfield-Jones SE, Greaves MW. Urticarial vasculitis—response to gold therapy. J R Soc Med. 1991;84:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Highet A. Urticarial vasculitis and IgA myeloma. Br J Dermatol. 1980;102:355–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes R, Lacour JP, Baldin B, Reverte M, Ortonne JP, Passeron T. Urticarial vasculitis secondary to H1N1 vaccination. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:651–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang X, Lu M, Ying Y, Feng J, Ye Y. A case report of double-filtration plasmapheresis for the resolution of refractory chronic urticaria. Ther Apher Dial. 2008;12:505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones RR, Bhogal B, Dash A, Schifferli J. Urticaria and vasculitis: a continuum of histological and immunopathological changes. Br J Dermatol. 1983;108:695–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones JM, Reich KA, Raval DG. Angioedema in a 47-year-old woman with hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112:90–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kano Y, Orihara M, Shiohara T. Cellular and molecular dynamics in exercise-induced urticarial vasculitis lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kartal O, Gulec M, Caliskaner Z, Nevruz O, Cetin T, Sener O. Plasmapheresis in a patient with “refractory” urticarial vasculitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2012;4:245–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulthanan K, Cheepsomsong M, Jiamton S. Urticarial vasculitis: etiologies and clinical course. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2009;27:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee JS, Loh TH, Seow SC, Tan SH. Prolonged urticaria with purpura: the spectrum of clinical and histopathologic features in a prospective series of 22 patients exhibiting the clinical features of urticarial vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:994–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis JE. Urticarial vasculitis occurring in association with visceral malignancy. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1990;70:345–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipsker D, Veran Y, Grunenberger F, Cribier B, Heid E, Grosshans E. The Schnitzler syndrome. Four new cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loricera J, Calvo-Rio V, Ortiz-Sanjuan F, Gonzalez-Lopez MA, Fernandez-Llaca H, Rueda-Gotor J, Gonzalez-Vela MC, Alvarez L, Mata C, Gonzalez-Lamuno D, Martinez-Taboada VM, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Blanco R. The spectrum of paraneoplastic cutaneous vasculitis in a defined population: incidence and clinical features. Medicine (Baltimore). 2013;92:331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macêdo PA, Garcia CB, Schmitz MK, Jales LH, Pereira RM, Carvalho JF. Juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis associated with urticarial vasculitis syndrome: a unique presentation. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3643–3646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marthur R, Tochill PJ, Johnston ID. Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency with lymphoma causing recurrent angioedema. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69:646–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDuffie FC, Sams WM, Jr, Maldonado JE, Andreini PH, Conn DL, Samayoa EA. Hypocomplementaemia with cutaneous vasculitis and arthritis. Possible immune complex syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1973;48:340–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehregan DR, Hall MJ, Gibson LE. Urticarial vasculitis: a histopathologic and clinical review of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michel BA, Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Calabrese LH. Hypersensitivity vasculitis and Henoch-Schonlein purpura: a comparison between the 2 disorders. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:721–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mills JA, Michel HA, Bloch DA, Calabrese LH, Hunder GG, Arend WP, Edworthy SM, Fauci AS, Leavitt RY, Lie JT, Lightfoot RW, Jr, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Stevens MB, Wallace SL, Zvaifler NJ. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1114–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oi M, Sath T, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K. Infectious urticaria with purpura: a mild subtype of urticarial vasculitis? Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parker SC, Greaves MW, Breathnack AS. Platelet activation and aggregation in urticarial vasculitis. Br J Dermatol. 1991;125:97. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pasero G, Olivieri I, Gemignami G, Vitale C. Urticaria/arthritis syndrome: report of four B51 positive patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 1989;48:508–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peroni A, Colato C, Zanoni G, Girolomoni G. Urticarial lesions: if not urticaria, what else? The differential diagnosis of urticaria: part II. Systemic diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:557–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rufino Hernandez M, Escamilla Cabrera B, Alvarez Sosa D, Garcia Rebollo S, Losada Cabrera M, Hernandez Marrero D, Alvarez Gonzalez A, Torres Ramirez A, Maceira Cruz B, Lorenzo Sellares V. Patients treated with plasmapheresis: a case review from University Hospital of the Canary Islands. Nefrologia. 2011;31:415–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saigal K, Valencia IC, Cohen J, Kerdel FA. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis with angioedema, a rare presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus: rapid response to rituximab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:S283–S285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schnitzler L. Lesions urticariennes chroniques permanents (erytheme petaloide?). Cas cliniques No 46B. J Dermatol Angers. 1972; October 28. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwartz HR, McDuffie FC, Black LF, Schroeter AL, Conn DL. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: association with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1982;57:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sprossmann A, Muller RP. Urticarial vasculitis syndrome in metastatic malignant testicular teratoma. Hautarzt. 1994;45:871–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strickland D, Ware R. Urticarial vasculitis: an autoimmune disorder following therapy for Hodgkin’s disease. Med Paediat Oncol. 1995;25:208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tosoni C, Lodi-Rizzini F, Cinquini M, Pasolini G, Venturini M, Sinico RA, Calzavara-Pinton P. A reassessment of diagnostic criteria and treatment of idiopathic urticarial vasculitis: a retrospective study of 47 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:166–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Venzor J, Lee WL, Huston DP. Urticarial vasculitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2002;23:201–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weldon D. When your patients are itching to see you: not all hives are urticaria. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson D, McCluggage WG, Wright GD. Urticarial vasculitis: a paraneoplastic presentation of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41:476–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wisnieski JJ, Naff GB. Serum IgG antibodies to C1q in hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wisnieski JJ. Urticarial vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolf K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffel A. Chapter 164, Cutaneous necrotizing venulitis. In: Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008:599–606. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Worm M, Sterry W, Kolde G. Mycophenolate mofetil is effective for maintenance therapy of hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]